“Nice White Ladies Don’t Go Around Barefoot”: Racing the White Subjects of The Help (Tate Taylor, 2011)

Marie-Alix Thouaille

Introduction

In 1989 Kimberlé Crenshaw argued that “Black women are theoretically erased” by the “single-axis framework that is dominant in antidiscrimination law and that is also reflected in feminist theory and antiracist politics” (139). Taking issue with the damaging “tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis” (139), Crenshaw proposed “intersectionality” as a framework to conceptualise the lives of those “multiply-burdened” by intersecting experiences of gender and race (140). And yet, twenty-seven years on, the word “woman” still seems to connote the modifiers “white”, “middle-class” and “heterosexual”. The favoured subject of postfeminist media culture, “who is white and middle class by default” (Tasker and Negra 2), seems to colonise even narratives of blackness. Indeed, on 12 June 2015, Ruthanne and Larry Dolezal told the press that their daughter Rachel, a professor of Africana studies at Eastern Washington University and president of the Spokane NAACP chapter, had been misrepresenting “herself as an African American, or a biracial person” (Elgot). Journalists, media commentators and bloggers pored over Dolezal’s personal photographs, family history and TV interviews, in an attempt to disentangle her ostensibly “transracial” identity. [1] Dolezal’s self-identification came under fire because “instead of acknowledging and using her privilege to advocate for a marginalised community, she appropriated from that community for professional benefit” (Oyeniyi). As Doyin Oyeniyi powerfully argued, since Dolezal “was paid to write and speak about her claims of growing up black, black women who could have filled those positions didn’t get to”; in the end, “Dolezal could have been an ally, but instead, she was an appropriator”.

The same accusation might be levelled at Kathryn Stockett, her bestselling novel The Help (2009) and its blockbuster film adaptation (Tate Taylor, 2011). [2] Both Stockett and her aspiring author protagonist Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan (Emma Stone) are embedded in a striking proliferation of diegetic and extradiegetic authorial appropriations. Skeeter happily recycles Aibileen Clark’s (Viola Davis) domestic tips for her Jackson Journal column and uses the narratives of numerous black maids in the writing of the text-within-the-text. Moreover, Stockett herself allegedly based the character of Aibileen on her brother’s long-time maid. [3] In other words, not only is The Help a text within which a white woman author profits from the lives of women of colour, it is also a text written by a white woman author who profits from the real and/or imagined lives of women of colour. Like Dolezal, both Stockett and Skeeter rely on their invisible whiteness—in other words, their unexamined, unchecked, white privilege—in order to inhabit, and appropriate from, marginalised women’s subjectivities. This article posits that our continuing cultural reluctance to recognise whiteness and its privileges in American society ultimately perpetuates racism through the erasure of women of colour. Through an analysis of The Help’s filmic strategies for inscribing whiteness as a form of absence, I expose the ways in which Skeeter’s invisible whiteness legitimises her appropriative project under the umbrella of postracism. In this article, unless otherwise specified, The Help refers to Taylor’s adaptation rather than Stockett’s novel.

However, this article goes on to argue that, as a film, The Help simultaneously offers a sceptical reading of Stockett’s and Skeeter’s appropriative practices. Despite emerging from, and operating within, the overwhelmingly white and male machinery of mainstream Hollywood, Taylor’s film attempts to challenge the concept of invisible whiteness. [4] The film notably celebrates the labour, stories and voices of its black protagonists Minny Jackson (Octavia Spencer) and Aibileen, in an attempt to undermine the novel’s appropriative project(s). Crucially, the film also works to “race” one of its white female characters, Celia Foote (Jessica Chastain), finding ways to make whiteness visible, embodied and accountable. The interrogation of the cultural invisibility of whiteness is essential to the dismantling of the equation of whiteness with humanity (Dyer, White 1–2). Only then can we contest the ways in which neoliberalism and postracism interplay to reify middle-class whiteness as the default subject position for women in screen media in the twenty-first century.

Critical Contexts

Ideologies such as postfeminism and postracism are “rooted in a generally decent, if misguided, belief that our society has reached a moment in which we are living out our lives on a level playing field” (Vavrus 222). [5] In both articulations, the prefix “post” marks the perceived “‘after’ moment when inequality is over” (Joseph, “Hope is finally making a comeback” 61). Variously theorised as “colorblind racism”, “colormute”, “racial apathy”, or “post-civil rights” (Joseph, “Tyra Banks is Fat” 239), postracism spotlights the individual as a savvy and empowered neoliberal consumer. Under the neoliberal postracist imperative, the “autonomous, calculating self-regulating subject of neoliberalism” is understood to freely opt in and out of raced identities (Gill 164). Indeed, as Charles A. Gallagher explains, “affirming racial identity, like whites who have the luxury of an optional ethnicity” such as Irishness, “is an individual, voluntary decision” (29). In reality, this “voluntary decision” is simply not available to raced subjects. This “colourblind narrative” crossfertilises with the fallacy of the meritocratic American Dream to deliver particularly damaging fictions of equality (Gallagher 29). By suggesting that success is freely available to all,

[p]ostracism both relies on, and reproduces, the age-old mythology of American exceptionalism under capitalism: that by pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps, working hard, acting ethically, playing fair, and not asking for help it is possible to achieve the American dream of success. (Ono 228–9)

Gallagher’s study, “Color-blind Privilege: The Social and Political Functions of Erasing the Color Line in Post Race America”, evidences the ways in which white people’s allegiance to colour blindness perpetuates racism by allowing “whites to imagine that being white or black or brown has no bearing on an individual’s or a group’s relative place in the socio-economic hierarchy” (22). Barack Obama’s election in 2008 marks the ultimate validation of postracist thinking: “That a Black man became the president of the United States implies that past racial barriers to occupying that office are now gone” (Ono 228). [6]

This desire to erase the colour line strategically suppresses America’s notorious track record of violent cultural appropriation. Defined as “the taking—from a culture that is not one’s own—of intellectual property, cultural expressions or artefacts, history, and ways of knowledge” (Marchand B6), cultural appropriation reproduces historical patterns of subjugation of people of colour. In White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side, James Snead discusses Disney’s Song of the South (Wilfred Jackson and Harve Foster, 1946) and reflects on Hollywood’s tendency to perform and profit from black texts and stories in a way that ultimately excludes the stories’ initial originators:

The most incisive statement the film makes about Johnny’s relationship to Uncle Remus, however, recalls the very process (reminiscent of slavery itself) whereby Harris first and Disney secondly appropriate and then market Uncle Remus’ African narratives, without the black bard reaping any benefits from his labors. If Johnny’s “black” parent teaches the content and technique of his storytelling genius, his “white” precursors (Harris and Disney) seem in the end to have taught him the art of usurping and exploiting those stories, for by the ending of the movie Uncle Remus has been made obsolete! (96–7)

Snead terms this phenomenon “exclusionary emulation”, or the “principle whereby the power and trappings of black culture are initiated while at the same time their black originators are segregated away and kept at a distance” (60). This double entanglement of invocation/ segregation is, I argue, just as relevant to mid-2000s postracist media culture as it was in the 1940s.

Like Richard Dyer, I believe it is crucial to resist the white-centric assumption that being white signals the absence of race, and in so doing, to render whiteness and white privilege visible. Dyer argues that:

As long as race is something only applied to non-white peoples, as long as white people are not racially seen and named, they/we function as a human norm. Other people are raced, we are just people.

There is no more powerful position that that of being “just” human. The claim to power is the claim to speak for the commonality of humanity. Raced people can’t do that—they can speak only for their race. But non-raced people can, for they do not represent the interests of a race. The point of seeing the racing of whites is to dislodge them/us from the position of power, with all the inequities, oppression, privileges and sufferings in its train, dislodging them/us by undercutting the authority with which they/we speak and act in and on the world. (White 1–2)This passage is worth quoting at length because it exposes the exclusionary mechanisms underpinning claims of “universality”. The assumption that white people are “just people” legitimises the marginalisation of people of colour while keeping white privilege invisible and uncontested. Invisibility is similarly central to Peggy McIntosh’s conceptualisation of white privilege as an “unearned advantage and conferred dominance”, which functions as an “invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear and blank cheques” (70; emphasis added). As Dyer notes, the “invisibility of these assets is part and parcel of the sense that whiteness is nothing in particular, that white culture and identity have, as it were, no content” (White 9). The conceptual link between whiteness and absence underpins the spurious belief that “having no content, white people … think, feel, and act for all people” (9). This results in white people creating “dominant images of the world” without “quite see[ing] that they thus construct the world in their own image” (9). In this case study, I employ Dyer and McIntosh’s frameworks to race the white subjects of The Help and, in so doing, to challenge its postracist agenda.

Invisible Whiteness

Through her repeated linkage with absence, Skeeter best exemplifies The Help’s strategies for inscribing whiteness as “having no content” (Dyer, White 9). Building on Dyer, I argue that this invisibility functions as a vehicle for Skeeter’s problematic claims of colour-blind universality. [7] From the start of the film, her femininity is coded in terms of its conspicuous “lacks”. Note particularly the repetition of “no” and “not” in Aibileen’s introductory voiceover: “The young white ladies of Jackson … Oh Law, was they having babies. But not Miss Skeeter. No man, and no babies.” The Help’scostumes similarly work to set Skeeter apart from her Jackson Junior League friends. In her first appearance at Bridge Club, in a straight tweed dress, wide flat shoes, carrying a business-like leather satchel, her uncontrollably curly ginger hair tied back and no visible makeup, Skeeter starkly contrasts with her best friends Hilly Holbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard) and Elizabeth Leefolt (Ahna O’Reilly). Their knee-length, flared, floral-patterned dresses, clinched at the waist, emphasise the curves so lacking in the flat-chested and lanky Skeeter. Their smooth, shiny and elaborate beehives, sophisticated makeup and expensive jewellery signal their graceful elegance. Skeeter is unpolished by comparison: she bites her nails, drives her parents’ van with motor grader in tow to a date (ruining the labour of the “Shinolator”) and in her trademark frankness terms oysters “a vehicle for crackers and ketchup”. The project of fixing Skeeter’s “lacks” preoccupies Skeeter’s mother, Charlotte Phelan (Allison Janney), who repeatedly attempts to police Skeeter’s noncompliant behaviour and appearance.

Crucially, the film neutralises Skeeter’s potentially queer-coded femininity. Firstly, Skeeter’s “awkwardness” is defused by the warmth and charm of Emma Stone’s performance, as well as her screen legacy. Skeeter seems to exist in a continuum of Stone’s roles in The House Bunny (Fred Wolf, 2009), Easy A (Will Gluck, 2010), Crazy, Stupid, Love (Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, 2011), or more recently, Aloha (Cameron Crowe, 2015), in which she embodies the socially awkward pretty girl who is eventually recuperated into conventional heteronormative coupledom. [8] Secondly, the film counteracts Skeeter’s subversive femininity narratively. Reading her daughter’s “lacks” as deviant, Charlotte asks whether Skeeter has had “unnatural thoughts about girls or women”. At this point, the scene is played for laughs. In the context of the increased visibility of LGBTQIA+ issues in American culture in the early 2010s, Charlotte’s suggestion that “there’s a special root tea for that now” is the target of the film’s derision. However, when Skeeter responds, “Mother! I want to be with girls … as much as you want to be with Jameso [the Phelans’ black male domestic] ... Unless, of course, you do?” the film derails its own political critique. Not only does the film fail to interrogate its problematic suggestion that interracial relationships and lesbianism are abhorrent, but as the camera pans to follow Skeeter’s stroppy, childish run down the stairs, the scene’s political potential has been subsumed into a more traditional exasperated mother/daughter dynamic. In this way, the film suggests that Skeeter’s ostensibly subversive “lacks” are in fact bound up with another: a lack of maturity. In other words, she is not really rebellious; she is merely behaving like a sulking adolescent.

Skeeter’s childishness is particularly apparent in contrast to Harper & Row editor Elaine Stein (Mary Steenburgen). While clad in stripy pyjamas, Skeeter ineffectually hides from her mother in the pickle-lined pantry of her parents’ rural plantation house. On the other end of the line, Elaine Stein sits in a “room of her own”: a large office overlooking Manhattan [Figures 1–2]. Noting the incongruity of Skeeter’s situation, she exclaims “for God’s sake, you’re a twenty-three-year-old educated woman, go get yourself an apartment!” In subsequent conversations, Stein gives Skeeter advice while dining out with two attractive young men, sipping cocktails and eating with chopsticks, or sitting in her stylish New York apartment wearing silk pyjamas. In the film, urban, modern and sexually savvy New Yorker Stein embodies the singleness in “superlative style” promised by Helen Gurley Brown’s 1962 bestseller Sex and the Single Girl (11). In comparison, Skeeter strikes the viewer as being particularly naïve and childlike, admitting to love interest Stuart Whitworth (Chris Lowell): “I’ve never really dated anyone before.” Charmed by this revelation of sexual innocence, Stuart’s expression softens. He responds: “Well, that must be it then … I’ve never met a woman who says exactly what she means.” Untrained in the arts of intrigue, Skeeter exercises the same disarming naïveté and integrity in her professional life, notably rejecting Minny’s suggestion of “making maids up” because “it wouldn’t be real”.

Figures 1 and 2: Skeeter (left) and Elaine Stein (right) in contrasting “rooms of their own”.

The Help (Tate Taylor, 2011). Dreamworks. Screenshots.

Underlying Skeeter’s characterisation is this sense of “lack”: she is marked by the conspicuous absence of a husband, of children, of conventional markers of femininity. Her childish naïveté is also an absence, the absence of “polluting” experience. In depicting Skeeter through absence and noninscription, the film reifies the claim that whiteness has “no content” (Dyer, White 9). Skeeter is a tabula rasa. In representing the absence of race, Skeeter embodies Dyer’s “just human” who can “claim to speak for the commonality of humanity” (2). This entitlement to universality goes hand in hand with Skeeter’s characterisation as a passive editorial vehicle devoid of a personal agenda. As the book nears its final stages, Stein advises her to “put something personal in there, write about the maid who raised you.” The use of the adjective “personal” suggests that, despite the essential contributions of women of colour, only the white woman’s account can be deemed “personal”. In a passage absent from the film, Skeeter finds out the truth about Constantine, [9] and opts to excise the episode from her own narrative:

That afternoon, I call Aibileen at home. “I can’t put it in the book,” I tell her. “About mother and Constantine. I’ll end it when I go to college. I just … I know I should. I know I should be sacrificing as much as you and Minny and all of you. But I just can’t do that to my mother.”

“No one expects you to, Miss Skeeter. Truth is, I wouldn’t think real high of you if you did.” (Stockett 361)This scene is highly suspect: although the maids have risked their livelihoods and safety to take part in the project, it is Skeeter’s “personal” risk that is prioritised. Both this passage, and its conspicuous absence from the film, nonetheless highlights the realities of editorial labour: an editor is not a passive medium for truth, but an individual who makes strategic choices. By excluding this scene from the adaptation, the film fallaciously portrays Skeeter as a passive figure in the authorial process—another kind of “lack”.

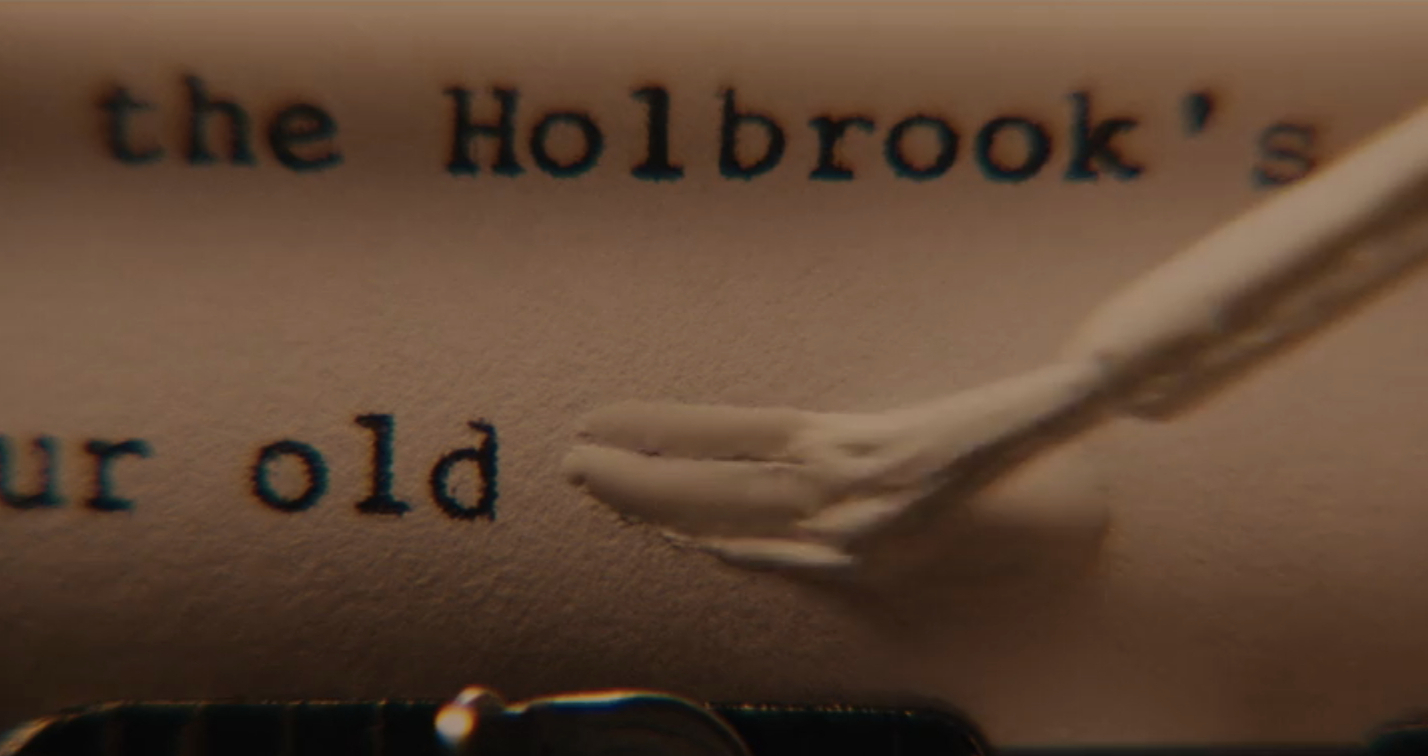

Even when Skeeter makes a significant, intentional editorial change to the Jackson Junior League newsletter, the scene is characterised by whiteness and absence. In a close-up of the typescript Skeeter is working on late one night, she whites out the word “coats” from the sentence “Come on by the Holbrook’s and drop off your old coats” [Figure 3]. The camera then elliptically cuts to Skeeter asleep on her bed. The viewer can later infer that Skeeter substituted the word “coats” for “commodes”, as a multitude of toilets, white receptacles of blackness symbolising the miscegenation Hilly Holbrook hysterically fears, are dropped off on the Holbrooks’ front lawn. In this scene, Hilly plays the part of the defiled white woman, whose immaculate, suburban whiteness has been polluted, running and yelling as members of the community document the event. Devastated, she cradles her “Yard of the Month” sign incongruously planted amongst the commodes. Crucially, Skeeter is never shown making the final inscription: we are only shown the absence of “coats”. By withholding the shot of Skeeter making the final edit, the film maintains her linkage with absence, whiteness and invisibility. This adaptive decision, in “whiting out” the evidence of Skeeter’s guilt, perpetuates the equation of whiteness with innocence. Keeping her culpability offscreen also means Skeeter is never taken to task for this stunt; as a white subject who is not racially “seen”, she cannot be held accountable.

Figure 3: Skeeter’s invisible guilt. The Help. Dreamworks.Screenshot.

Disappearing Whiteness

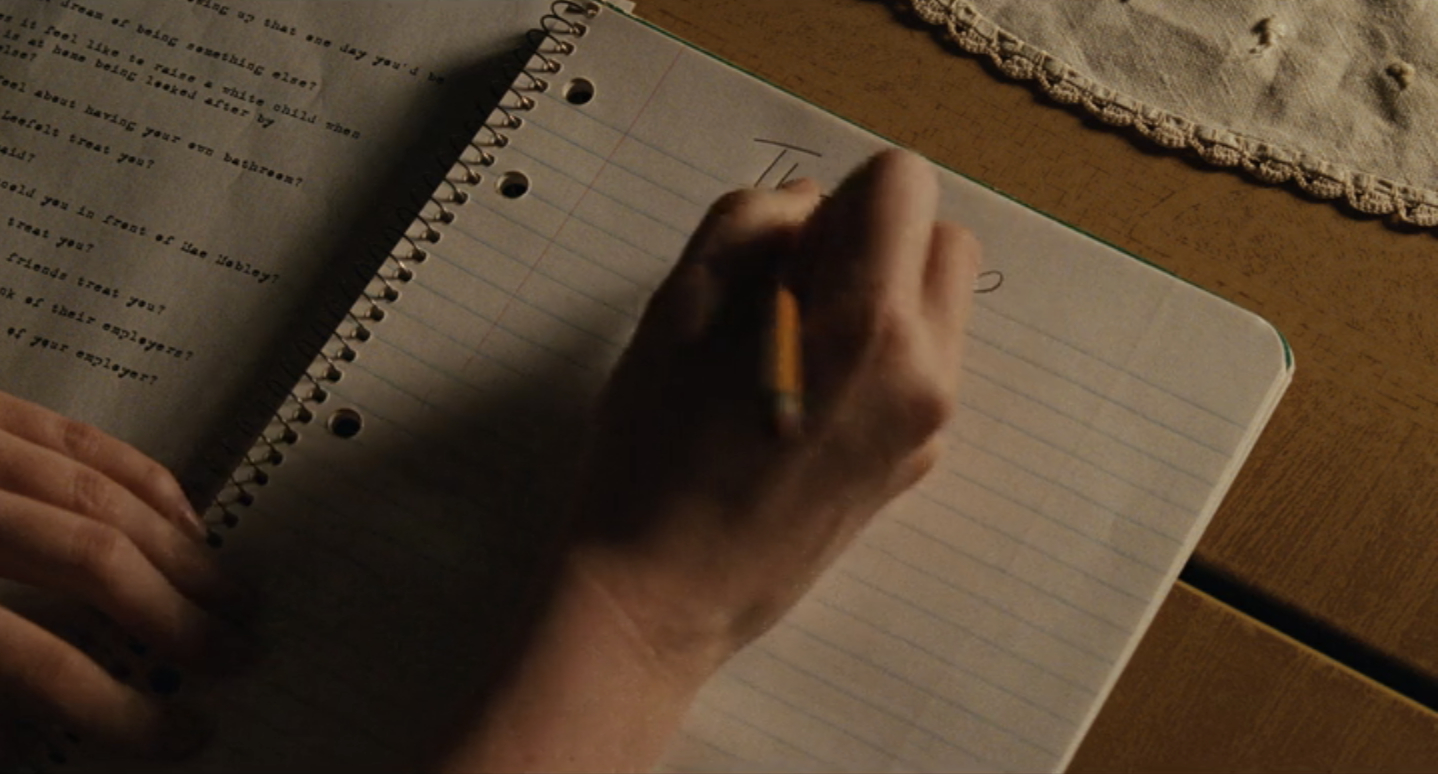

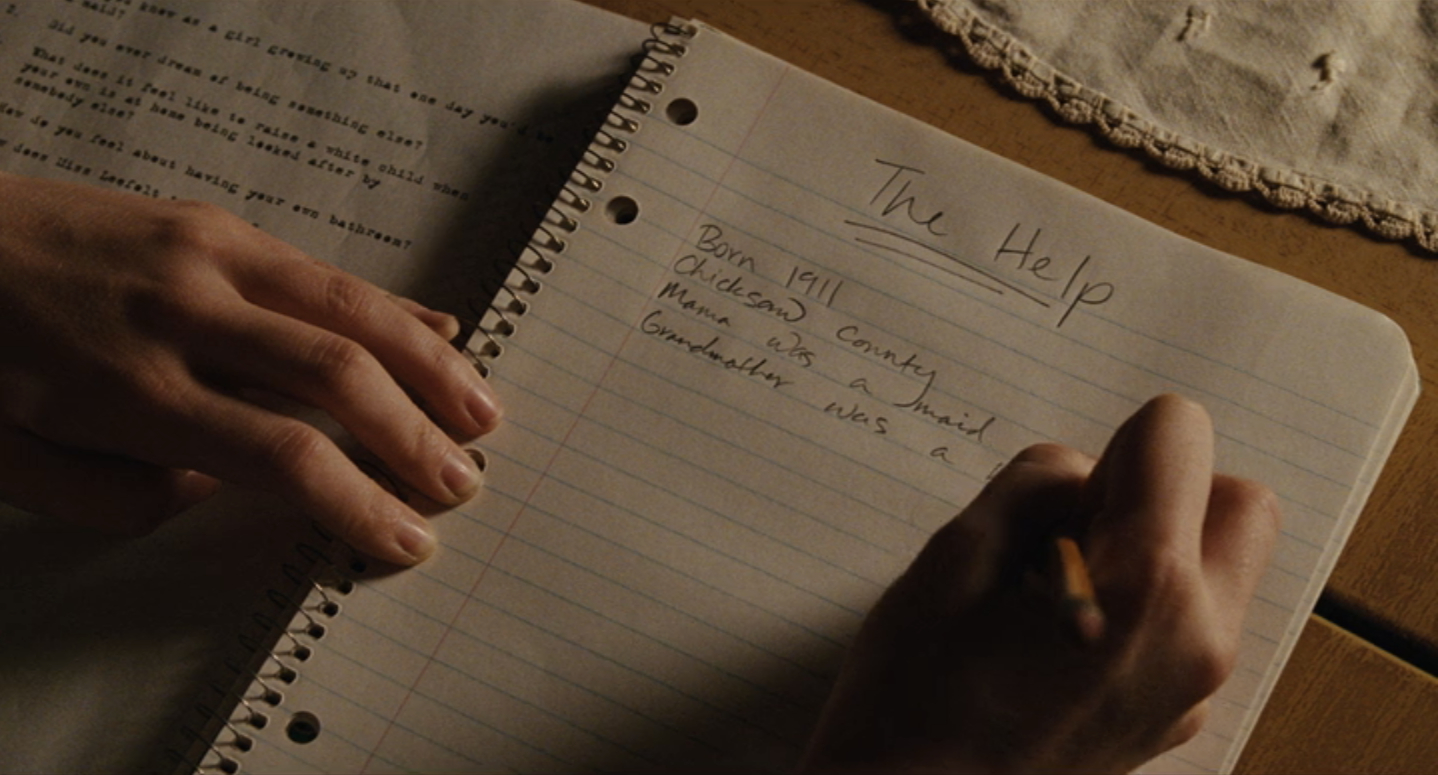

Reading against the grain of this arguably postracist film, I contend that The Help derails its problematic narrative of invisible whiteness in order to foreground the work of Aibileen. Exploiting the rhetoric of whiteness as absence, Skeeter’s white female body disappears almost entirely from the diegesis in the opening scene, a symbolic disappearance that allows the film to subvert its appropriative practice [Figures 4–7]. In the very first shot, a disembodied white hand clumsily writes and doubly underlines “The Help” at the top of a legal pad, the childlike handwriting hinting at Skeeter’s inexperience. The film then cuts to a medium shot of Aibileen. Looking straight at the camera, she begins speaking, as though directly to the viewer: “I was born 1911, Chickasaw County, Piedmont Plantation.” Even as she is asked a follow-up question, “And did you know as a girl growing up that one day you’d be a maid?”, the shot remains static, holding Aibileen’s gaze for over twenty seconds. At this point, instead of a reverse shot of Skeeter, the film cuts back to the legal pad, leaving the voice disembodied, connected only to a pair of white hands that note Aibileen’s responses. The sequence cuts back, for approximately twenty seconds, to Aibileen, who looks away, reflecting on what it “feel[s] like to raise a white child when your own child’s at home being looked after by somebody else.” Aibileen’s silence here betrays the inadequacy of Skeeter’s interview technique, which is failing to produce the necessary results. After a pause, Aibileen’s voiceover begins. The static camera, the lengthy shots, the withholding of the reverse shot(s) and Aibileen’s authoritative off-screen narration work to wrestle narrative control away from Skeeter. Turning invisibility against whiteness, the film indicates that Aibileen is the primary narrator of the film, which will eventually privilege black stories over white questions and thus carve out a dedicated space for Aibileen’s voice to be heard unframed and unmediated.

Figures 4–7: Skeeter’s disappearing whiteness, in the face of Aibileen’s narration. The Help.

Dreamworks. Screenshots.

Later, when the film returns to this initial interview, Viola Davis’s performance and her positioning within the frame accentuate Aibileen’s struggle for narrative control. As Skeeter desperately enumerates potential talking points to fill the silence (“Do you wanna talk about the bathroom? Or anything about Miss Leefolt?”), Aibileen looks increasingly tense and pained. Davis’s body language signals her character’s mounting anxiety and unease as she withdraws into herself, hiding her face behind her hands, clutching a tea towel for comfort and blinking slowly. The moment that she seizes control and suggests a different approach (“I thought I might write down my stories and read them to you. Ain’t no different from writing down my prayers”), Aibileen’s anxiety seems to lift. [10] Standing up straight, Aibileen now dominates the space within the frame. Although Skeeter says “go ahead”, Aibileen pauses before beginning to read. This marks the reversal of their dynamic: Skeeter must now follow Aibileen’s lead rather than the other way around. This is reinforced as Aibileen relaxes into her storytelling and laughs at a particular anecdote—Skeeter’s own laughter is delayed, signifying her new positioning in the narrative hierarchy. In fact, Aibileen dictates what Skeeter can and cannot write. In a sequence discussing Elizabeth’s bad parenting, Aibileen states, “Miss Leefolt should not be having babies.” Seeing Skeeter hesitate, she adds forcefully, “write that down.” Skeeter may be an author, but unlike Aibileen, she is refused authority over the text. As Skeeter functions as a proxy for the novel’s author, the film can be read as subversively undercutting Stockett herself. [11]

In the penultimate scene of the film, Minny, Aibileen and Skeeter meet for a final time. Skeeter announces that she has been offered a job in New York, but intends to turn it down. Surprised, Minny and Aibileen argue against her remaining in Jackson: “you ain’t got nothing left here but enemies in the Junior League … so don’t walk your white butt to New York, run it!” Aibileen tenderly extends her hand across the racial divide adding, “go find your life Miss Skeeter.” On one level, this scene seems to mark the validation of Skeeter’s appropriative behaviour: she is rewarded for coopting the maids’ narratives with a job offer and an opportunity to “find [her] life” beyond Mississippi. Like Uncle Remus in Songs of the South, having taught Skeeter the art of usurping black stories, Aibileen seems to have made herself obsolete. However, the film offers a competing interpretation. When Minny lays a hand on Aibileen’s shoulder and says “I’m gonna take care of Aibileen, and she’s gonna take care of me”, this sustaining black sisterhood now evidently excludes Skeeter, who has “nothing left but enemies in the Junior League”.

Importantly, the final sequence of the film focuses solely on Aibileen and her future: the camera pans alongside her as she walks out of the Leefolt’s front door and wipes her tears. Aibileen’s voiceover narrates her internal monologue: “No-one had ever asked me what it felt like to be me. Once I told the truth about that ... I felt free … My boy, Treelore, always said we going to have a writer in the family one day. I guess it’s gonna be me.” As the voiceover ends, the camera stops, pans back and upward, to reveal the long, deserted road that lies ahead for Aibileen [Figure 8]. The shot then remains static for the next three minutes, as she walks away and disappears into the distance. “The Living Proof” by Mary J. Blige, a cautiously hopeful track, begins to play: “It’s gonna be a long long journey / It’s gonna be an uphill climb … But I’m ready to carry on … I feel like I can do anything / And finally I’m not afraid to breathe.” The film’s closing shot, voiceover and song foreshadow Aibileen’s ongoing struggle for authorship and authorial identity. In the end, it is Treelore, not Skeeter, who offers Aibileen a future, finally rendering Skeeter obsolete.

Figure 8: “It’s gonna be a long long journey”. The Help. Dreamworks. Screenshot.

Visible Whiteness

The Help also challenges the concept of whiteness as invisibility by showing how Celia, a white woman, can be raced and seen. The film achieves this by first linking Celia to Marilyn Monroe iconography and then turning this identification against Celia to mark her as “Other”. As the phone rings at the Leefolt’s residence during Bridge Club, the film cuts to a pair of bare white legs in high-heeled flowered sling-back sandals [Figures 9–11]. The camera pans upward slowly, titillatingly revealing more of the female speaker’s crossing and uncrossing legs. Eventually, Celia is revealed in medium shot, wearing a short, tight, bright yellow jumpsuit showing off her generous curves; sunglasses, red nail polish and platinum blond hair. Celia’s costume and framing draw strong parallels with 1950s pin-up girls. Her giggly demeanour and ignorance (she seems unaware that she is being snubbed by the Jackson Junior League) moreover cement her identification with the stereotype of the “dumb blonde”. Dumb blondes like Monroe, Dyer explains, combine “overt, ‘natural’ sexuality … with a profound ignorance and innocence” (qtd. in Kuhn and Radstone 47). In Heavenly Bodies, Dyer goes on to argue that Monroe’s blondeness is intrinsically raced, since “platinum blondeness is the ultimate sign of whiteness”, a whiteness which is “racially unambiguous” and “keeps the white woman distinct” (40). However, in the logic of The Help, Celia’s association with Monroe iconography, as well as her lower-class accent, intonation and vocabulary function as markers of difference that compromise her status as invisibly white, because she neither looks nor sounds the part of a Junior League lady.

Figures 9–11: “I’m looking for some help.” The Help. Dreamworks. Screenshots.

Where the film characterises whiteness in terms of lack, Celia is linked with excess. As shown in the highly effective introductory sequence described above, she is simply “too much”: she is too giggly, her playsuit too tight and too short, her breasts too prominent: she tries “too hard”. Worse, her relationship with her husband Johnny Foote (Mike Vogel) is too sexual. While Hilly and Elizabeth’s marriages seem stale and devoid of sexual desire, their husbands mostly receding into the background, Johnny takes an active interest in his wife. After Celia hangs up the phone, he surprises her from behind and encloses her into a tight embrace. Suggestively indicating his sexual appetite, he says, “it’s lunch time and I’m suddenly hungry”. Much like Monroe, who was “obsessively” positioned “in such a way as to stand out in silhouette, a side-on tits and arse position” (Dyer, Heavenly Bodies 20), throughout the film costume and composition frame Celia as a sexual spectacle, in particular accentuating her voluptuous breasts and her buttocks. The film in fact fetishises Celia-as-body, as the camera lingers on her bare legs by the pool, or her cleavage at the Junior League Benefit Ball, in a medium shot that significantly cuts off Celia’s head [Figure 12]. More than any other woman in the film, Celia is cast as the recipient of the desiring male gaze. At the Benefit Ball, Hilly physically restrains her husband from eyeing Celia in her tight-fitting, pink, sequined dress. Later on, Celia drunkenly reveals that she had fallen pregnant before her marriage to Johnny and publicly vomits. These hypervisible bodily excesses signify Celia’s inability to keep her corporeality invisible—in other words, her failure to achieve invisible whiteness.

Figure 12: Headless Celia Foote as recipient of the desirous male gaze. The Help. Dreamworks. Screenshot.

As a white woman who fails to perform middle-class whiteness appropriately, Celia inhabits a classed “nouveau riche” and raced “white trash” subject position. In the novel, Minny observes that, “I can tell right off, [Celia’s] from way out in the country. I look down and see the fool doesn’t have any shoes on, like some kind of white trash. Nice white ladies don’t go around barefoot” (Stockett 31). This description, Tikenya Foster-Singletary observes, brings Celia’s “shoeless body into an uncomfortable racial space where she cannot easily be classified as a proper white woman” (97). Celia is also not a “proper white woman” because she chooses to share the small, intimate kitchen table with Minny instead of sitting at her own race-appropriate dinner table.[12] In sharing the intimate domestic space of the kitchen, Celia’s whiteness is “made visible” by the presence of the black female body (Dreher 4). The act of racially “seeing” Celia alongside Minny means that, in turn, the film yields a progressive and, crucially, nonappropriative cross-racial sisterly space. Unlike Skeeter, whose racial invisibility represents “universality” and authorises her appropriative practice of the Miss Myrna letters, Celia, as “white trash”, cannot successfully appropriate the work of a woman of colour. Her attempts to pass Minny’s cooking as her own are laughable, with her husband revealing that he was always aware of the charade: “Fried chicken and okra on the first night? Y’all could have at least put some cornpone on the table.” The absence of the raced and classed signifier (corpone) is an immediate giveaway that offsets the threat of appropriation. In the absence of the “proper white woman”, the black woman’s labour can be recognised and even celebrated.

By the end of the film, Celia has completed her apprenticeship with Minny and surprises the latter with a veritable feast. Significantly, however, Celia acknowledges her debt: she has cooked the fried chicken “just the way you [Minny] taught me.” The scene, which is absent from the novel, subverts the raced mistress/maid dynamic, as Minny is pictured seated at the dining room table being waited on by her white employer. Dyer importantly observes that the dumb blonde’s “lack of understanding of what is ‘obvious’ to ordinary people … stems from naivety and functions to show up the irrationality and/or hypocrisy of the social order” meaning this “stereotype has a subversive side which is sometimes overlooked” (qtd. in Kuhn and Radstone 47). Although Celia’s behaviour, in failing to adhere to societal norms separating black and white communities (calling Aibileen “miss”, cooking for, eating with, and hugging Minny), is initially coded as “ditzy”, The Help’s use of the dumb blonde stereotype is arguably subversive since it reveals and attempts to challenge the hypocrisy, malice and irrationality that underpin these norms.

Conclusion

It is not my intention to single out The Help as a particularly “good” or “bad” text in terms of its representational politics. Rather, I suggest that the film is symptomatic of a wider cultural problem. In one way, The Help works hard to locate racism as a problem of the past. This attempt to “post” race and promote colour-blindness may be well meaning, but, ironically, it results in the reifying of white privilege and the continued invisibility of whiteness, particularly in screen media. The Help’s use of a white protagonist to mediate and frame the stories of women of colour, for example, means those very women run the risk of erasure, of being made obsolete, of having their subjectivities colonised by whiteness. Yet, The Help simultaneously offers part of the solution. In taking over $216 million at the box office, for example, the film has arguably shown that there is a profitable space for “race” films in mainstream Hollywood, an industry that has seen a very modest but significant shift away from exclusively white control and exclusively white stories. [13] Moreover, the film works to make whiteness visible: when Minny says “don’t walk your white butt to New York, run it!”, Skeeter’s whiteness no longer equates to passivity and invisibility. Like Celia, Skeeter has finally become visibly white through her association with black women. In racing the white subject, we make whiteness accountable and discredit the fallacy of postracist colour blindness. Making whiteness visible means making whiteness visually and culturally specific and finally undercutting spurious claims to universality. Nice white ladies don’t go around barefoot, but when they do, they become allies, not appropriators.

Notes

[1] Dolezal’s use of the term “transracial” was particularly contested; see, for example, McFadden; Blaque.[2] Ironically, it was revealed that Dolezal had objected to The Help. She allegedly “wished the film had never been made. Her main dislike stemmed from all the money Kathryn Stockett, the author of the novel and a white woman, made off of this book and film. ‘Follow the money trail,’ Dolezal said. ‘A white woman makes millions off of a black woman’s story’” (Carrick).

[3] Ablene Cooper’s lawsuit was eventually dismissed under a statute of limitations (Chaney).

[4] Between 2005 and 2013, women comprised 16–17% “of all directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors, and cinematographers working on the top 250 (domestic) grossing films” (Lauzen 1). Similarly, a Los Angeles Times study revealed that in 2012 the membership of the Academy was “markedly less diverse than the moviegoing public”, with Oscar voters being “94% Caucasian and 77% male” (Horn, Sperling and Smith). The necessity of radical change was highlighted during the 2015 award season, under the Twitter hashtag #OscarsSoWhite. Later that year, during her historic win as the first woman of colour to win best actress in a drama series for her role in Shonda Rhimes’s How to Get Away with Murder (2014–), Viola Davis stated “let me tell you something, the only thing that separates women of colour from anyone else is opportunity. You cannot win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there” (McDonald). The 2016 Academy Awards nominations reignited the controversy, having “nominated an all-white group of acting nominees” for the second year running (Keegan and Zeitchik). To this day, Halle Berry remains the only woman of colour to have won the Oscar for best actress (Welsh).

[5] These “postideologies” are so similar in their reliance on the “double entanglement” (McRobbie 255) that key texts critiquing them have strikingly similar titles: see Tania Modelski and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. In this article, I have opted not to hyphenate the term “postracism”, in order to further highlight the mutually reinforcing synergy between postracism and postfeminism.

[6] The fact that Hillary Clinton came head-to-head with Obama in the Democratic Party primary moreover established a “double first” which was “offered up in the popular media as evidence of the United States emerging as a truly meritocratic state” (Joseph, “Hope is finally making a comeback” 59).

[7] See in particular Kathryn Stockett’s author’s note, in which she deploys claims of “universality” in order to avoid making her own whiteness accountable. She explains that, “I don’t presume to think I know what it really felt like to be a black woman in Mississippi, especially in the 1960s. … But trying to understand is vital to our humanity. In The Help there is one line that I truly prize: ‘Wasn’t that the point of the book? For women to realize, We are just two people. Not that much separates us. Not nearly as much as I thought’”(Stockett 451; emphasis in original). In Stockett’s logic, if she is “trying to understand” what it “really felt like to be a black woman in Mississippi,” then she is not guilty of appropriation, but involved in a universalist project “vital to our humanity”. Stockett therefore invites us to unsee her whiteness and see “just two people” instead. This use of “just” reminds us, once more that “there is no more powerful position than that of being ‘just’ human” (Dyer, White 2).

[8] Aloha director Cameron Crowe was widely criticised for casting Stone to play the role of Allison Ng, a pilot who describes herself as one-quarter Chinese, one-quarter Hawaiian and one-quarter Swedish. See Chris Lee and Jen Yamato.

[9] The truth about Constantine is substantially different in the parent novel. Constantine’s daughter, Lulabelle, is a “high yellow” who passes for white at an event at the Phelan residence. Charlotte kicks her out for “trying to act white” and asks Constantine to cut all ties with her daughter. In the film, on the other hand, Constantine’s daughter is named Rachel and does not attempt to pass for white.

[10] As Allison Graham has noted, the use of the word “stories” warrants interrogation.

[11] Shelley Cobb contends that female directors use the character of the diegetic woman author as “as a vehicle for representing the authorizing of the woman filmmaker” (1). I argue that Stockett’s The Help deploys a similar self-authorising strategy: aware of her potentially shaky claim to authority, Stockett creates the character of Skeeter (note the similarity in their names) to fictionally “authorise” the project.

[12] Minny embodies another kind of excess femininity, as her body and her language constantly threaten to spill out. In the novel she must remind herself to “Tuck it in, Minny. Tuck in whatever might fly out my mouth and tuck in my behind too” (Stockett 30). Foster-Singletary observes that Minny “is repeatedly described in terms of her excess” and that her “uncontained” body, including her “frequent pregnancies … represent uncontrolled blackness … her body pushes the boundaries of normality. She is too much—too much woman to be a lady, too much mouth for a maid, too black for her own good” (100).

[13] See particularly 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, 2013), which took$187 million at the box office and won three Oscars, and Selma (Ava DuVernay, 2014), which took $66 million and won an Oscar. While the increased visibility of black cultural producers such as Oprah Winfrey, Shonda Rhimes, Lee Daniels, Ava DuVernay and Steve McQueen is indeed a step forward, their success still remains “exceptional” in a predominantly white, male industry.

References

1. Blaque, Kat. “Why Rachel Dolezal’s Fake ‘Transracial’ Identity Is Nothing like Being Transgender—Take It from a Black Trans Woman Who Knows.” Everyday Feminism. 15 June 2015. Web. 5 July 2015. <http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/06/rachel-dolezal-not-transracial/>.

2. Blige, Mary J. “The Living Proof.” The Help. Geffen, 2011. CD.

3. Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013. Print.

4. Brown, Helen Gurley. Sex and the Single Girl. London: Frederick Muller, 1963. Print.

5. Carrick, Bridget. “Students Find The Help to Be Unhelpful.” The Gonzaga Bulletin. 6 Mar. 2012. Web. 17 June 2015. <http://www.gonzagabulletin.com/article_a15f6afe-4a1b-544b-b524-3461eb6adb5d.html>.

6. Chaney, Jen. “The Help Lawsuit against Kathryn Stockett Is Dismissed.” The Washington Post. 16 Aug. 2011. Web. 19 June 2015. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/celebritology/post/the-help-lawsuit-against-kathryn-stockett-dismissed/2011/08/16/gIQAiCWqJJ_blog.html>.

7. Cobb, Shelley. Adaptation, Authorship, and Contemporary Women Filmmakers. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. Print.

8. Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum (1989): 139–67. Print.

9. Dreher, Kwakiutl L. “‘I Really Need a Maid!’ White Womanhood in The Help.” Movies in the Age of Obama: The Era of Post-Racial and Neo-Racist Cinema. Ed. David Garrett Izzo. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. 3–14. Ebook.

10. Dyer, Richard. White. London: Routledge, 1997. Print.

11. ---. Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2004. Ebook.

12. Elgot, Jessica. “Civil Rights Activist Rachel Dolezal Misrepresented Herself as Black, Claim Parents.” The Guardian. 12 June 2015. Web. 17 June 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/12/civil-rights-activist-rachel-dolezal-misrepresented-herself-as-black-claim-parents>.

13. Foster-Singletary, Tikenya. “Dirty South: The Help and the Problem of Black Bodies.” Southern Quarterly 49.4 (2012): 95–107. Print.

14. Gallagher, Charles A. “Color-Blind Privilege: The Social and Political Functions of Erasing the Color Line in Post Race America.” Race, Gender & Class 10.4 (2003): 22–37. Print.

15. Gill, Rosalind. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10.2 (2007): 147–66. Print.

16. Graham, Allison. “‘We Ain’t Doin’ Civil Rights’: The Life and Times of a Genre, as Told in The Help.” Southern Cultures 20.1 (2014): 51–64. Print.

17. The Help. Dir. Tate Taylor. Dreamworks, 2011. Film.

18. hooks, bell. Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge, 2013. Print.

19. Horn, Joe, Nicole Sperling, and Doug Smith. “Unmasking Oscar: Academy Voters Are Overwhelmingly White and Male.” 19 Feb. 2012. Web. 20 Jan. 2016.

<http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/envelope/oscars/la-et-unmasking-oscar-academy-project-20120219-story.html>.20. Jones, Suzanne Whitmore. “The Divided Reception of The Help.” Southern Cultures 1 (2014): 7–25. Print.

21. Joseph, Ralina L. “‘Tyra Banks Is Fat’”: Reading (Post-)Racism and (Post-)Feminism in the New Millennium.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 26.3 (2009): 237–54. Print.

22. ---.“‘Hope Is Finally Making a Comeback’: First Lady Reframed.” Communication, Culture & Critique 4.1 (2011): 56–77. Print.

23. Keegan, Rebecca and Steven Zeitchik. “Oscars 2016: Here’s Why the Nominees are So White—Again.” Los Angeles Times. 14 Jan. 2016. Web. 05 Feb. 2016. <http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et-mn-all-white-oscar-acting-nominees-20160114-story.html>.

24. Kuhn, Annette, and Susannah Radstone. The Women’s Companion to International Film. London: Virago, 1990. Print.

25. Lauzen, Martha M. “The Celluloid Ceiling: Behind-the-Scenes Employment of Women on the Top 25 Films of 2014.” Centre for the Study of Women in Television and Film. 2015. Web. 28 May 2015. <http://womenintvfilm.sdsu.edu/files/2014_Celluloid_Ceiling_Report.pdf>.

26. Lee, Chris. “I’m Not Buying Emma Stone as an Asian-American in Aloha.” Entertainment Weekly. 29 May 2015. Web. 20 Jan. 2016. <http://www.ew.com/article/2015/05/29/im-not-buying-emma-stone-asian-american>.

27. Marchand, Phillip. “Dancing to the Pork Barrel Polka.” Toronto Star 5 Aug. 1992: B6. Print.

28. McDonald, Soraya Nadia. “‘You Cannot Win an Emmy for Roles that Are Simply Not There’: Viola Davis on Her Historic Emmys Win.” The Washington Post. 21 Sep. 2015. Web. 05 Feb. 2016.

<https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2015/09/21/you-cannot-win-an-emmy-for-roles-that-are-simply-not-there-viola-davis-on-her-historic-emmys-win/>.29. McFadden, Syreeta. “Rachel Dolezal’s Definition of ‘Transracial’ Isn’t Just Wrong, It’s Destructive.” The Guardian. 16 June 2015. Web. 5 July 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/16/transracial-definition-destructive-rachel-dolezal-spokane-naacp>.

30. McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies.” Race, Class and Gender: An Anthology. Ed. Margaret L. Andersen and Patricia Hill Collins. Belmont: Wadsworth, 1992. 70–81. Print.

31. McRobbie, Angela. “Post‐Feminism and Popular Culture.” Feminist Media Studies 4.3 (2004): 255–64. Print.

32. Modleski, Tania. Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a “Postfeminist” Age. New York and London: Routledge, 1991. Print.

33. Ono, Kent A. “Postracism: A Theory of the ‘Post-’ as Political Strategy.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 34.3 (2010): 227–33. Print.

34. Oyeniyi, Doyin. “Rachel Dolezal Could Have Been an Ally, But Ultimately She’s an Appropriator.” Bustle. 15 June 2015. Web. 19 June 2015. <http://www.bustle.com/articles/90144-rachel-dolezal-could-have-been-an-ally-but-ultimately-shes-an-appropriator>.

35. Rose, Nikolas S. Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. Print.

36. Selma. Dir. Ava DuVernay. Pathé, 2014. Film.

37. Smith, Valerie. “Black Women’s Memories and The Help.” Southern Cultures 20.1 (2014): 26–37. Print.

38. Snead, James A. White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side. New York: Routledge, 1994. Print.

39. Song of the South. Dir. Wilfred Jackson and Harve Foster. Walt Disney Productions, 1946. Film.

40. Stockett, Kathryn. The Help. London: Penguin, 2010. Print.

41. ---. “Too Little Too Late: Kathryn Stockett in Her Own Words.” The Help. London: Penguin, 2010. 447-451. Print.

42. Stone, Emma, perf. Aloha. Dir. Cameron Crowe. Twentieth Century Fox, 2015. Film.

43. ---. Crazy, Stupid, Love. Dir. Glenn Ficarra and John Requa. Carousel Productions, 2011. Film.

44. ---. Easy A. Dir. Will Gluck. Screen Gems, 2010. Film.

45. ---. The House Bunny. Dir. Fred Wolf. Relativity Media, 2009. Film.

46. Tasker, Yvonne, and Diane Negra, eds. Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Durham: Duke UP, 2007. Print.

47. 12 Years a Slave. Dir. Steve McQueen. Summit Entertainment, 2013. Film.

48. Vavrus, Mary Douglas. “Unhitching from the ‘Post’ (of Postfeminism).” Journal of Communication Inquiry 34.3 (2010): 222–27. Print.

49. Welsh, Daniel. “Oscars 2016: Academy Award-Winner Halle Berry Admits ‘Heartbreak’ over Race Row.” The Huffington Post. 3 Feb 2016. Web. 5 Feb 2016.

<http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2016/02/03/oscars-racism-diversity-row-halle-berry_n_9149364.html>.50. Yamato, Jen. “The Unbearable Whiteness of Cameron Crowe’s ‘Aloha’: A Hawaii-Set Film Starring Asian Emma Stone.” The Daily Beast. 28 May 2015. Web. 20 Jan. 2016. <http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/05/28/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-cameron-crowe-s-aloha-a-hawaii-set-film-starring-asian-emma-stone.html>.

Suggested Citation

Thouaille, M-A. (2015) '“Nice white ladies don’t go around barefoot”: racing the white subjects of The Help (Tate Taylor, 2011)', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 10, pp. 96–112. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.10.06.

Marie-Alix Thouaille is a CHASE-funded doctoral student at the University of East Anglia (UEA). Her research studies the figure of the single woman author in contemporary American film since 1990. She is particularly interested in the postfeminist intersections of gender, race, sexuality and authorship and the ways in which popular film mediates the figure of the unruly creative woman.