The Taming of the Bronies: Animals, Autism and Fandom as Therapeutic Performance

Maria Pramaggiore

The emergence of the Brony fandom in 2011 in the wake of toy and game manufacturer Hasbro’s 2010 reboot of the My Pretty Pony (1981)/My Little Pony (1983) franchise from the 1980s captured the attention of journalists and scholars alike. Numerous articles and essays explore the subversive potential of these adult male fans of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic (2010–), hereafter MLP:FiM, an animated toy-based children’s series created by Lauren Faust, who previously worked on Powerpuff Girls (1998–2005). The programme is organised around a group of characters known as “the Mane Six” who are hybrid, anthropomorphic, talking ponygirls.

The Brony subculture of adolescent boys and adult men developed within the online environment of the “Comics & Cartoons” discussion board of 4chan, an image-board site established in 2003 by 15-year-old Christopher Poole. 4chan has been described by The Guardian’s Sean Michaels as “lunatic, juvenile, brilliant, ridiculous, and alarming” and has been associated with numerous Internet attacks and pranks, most recently and notoriously the Gamergate controversy. The Gamergate drama, in which three feminist game developers/critics who decried the sexism of the gaming industry were subjected to a coordinated campaign of vicious online attacks and threats to their personal safety, caused Tom Mendelsohn of The Independent to call 4chan “a digital plaguepit of particularly virulent woman-hatred”. In short, the crucible that formed the Brony fandom was a contentious online environment whose discourse was mired in gender anxieties.

MLP:FiM draws from both anime and kawaii aesthetics and partakes of the “sparklefication” and “postfeminist luminosity” that Mary Celeste Kearney associates with post-girl-power, girl-centred animations such as Frozen (263). In MLP:FiM, Flash animation, professional voice actors and scripts written with both children and adults in mind anchor educational narratives set in the nearly all-female and nearly all-equine town of Ponyville in the land of Equestria, which is ruled by sibling Princesses Celestia and Luna. There is a complex taxonomy to this hierarchical equine culture: there are earth ponies, Pegasus ponies, unicorns, allicorns, crystal ponies and mermares. Each episode focuses on a value such as loyalty, kindness or sincerity. The programme itself may be utterly unremarkable as an anthropomorphic animation aimed at children and adults—a pink-hued SpongeBob Squarepants—but the Brony fandom and its controversy represent a situation in which “the media text to which a community might seem to be devoted … is secondary to the communities themselves” (Driscoll and Gregg 575).

Figure 1: Alicorn Princess Luna, joined by her sister Princess Celestia, lectures unicorn pony Twilight Sparkle. “You’ll Play Your Part.” From “Twilight’s Kingdom Part 1”, My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, Season 4 Episode 25, 2014, Hub Network. Screenshot.

In “Of Ponies and Men: My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic and the Brony Fandom”, Venetia Laura Delano Robertson offers an insightful and definitive overview of the fandom and the issues that it raises, including its self-conscious challenge to normative masculinity. No work to date, however, considers the specificity of the animal that the MLP:FiM series relies upon to convey its homilies of loyalty, friendship and personal growth to its target audience of young girls or questions its significance to Brony fan practices. In fact, Robertson asserts that the human-equine relationship is irrelevant to the emotional dynamics of the fandom (and vice versa), proposing that the MLP:FiM ponies, when considered as horses, are of interest only because they reiterate gender stereotypes governing appropriate animal-human pairings. She writes:

While the ponies are integral to the Bronies’ emotional investment in the show, this relationship says little about the relationship of humans to horses, except perhaps the obvious problems with the dichotomy of horses for boys, ponies for girls. (31)

In assessing the Brony fandom and, in particular, its much vaunted challenge to gender norms, I find myself in disagreement with Robertson on this point. I will argue the case that the rhetoric of the Brony fandom resonates in important ways with real-world equine performances, especially therapeutic performances. I also contend that it may not be coincidental that the horse plays such a central role in a fandom concerned with denaturalising gender boundaries, given that the horse’s significance to moving image representation has always been liminal, linked to its capacity for physical and metaphorical transportation. Thus, I hope to demonstrate that the gendered dynamics of the Brony fandom are implicated in the equine imaginary, a term I have defined elsewhere as humankind’s cultural, aesthetic, economic and affective investment in the horse (Pramaggiore). The equine imaginary does not operate merely at the representational level, with the myriad imagistic projections that humans generate in relation to horses; it also draws from and informs the way humans breed, admire, exploit and destroy horses for sport, work, food or companionship.

The MLP:FiM ponies represent far more than spunky pastel-coloured postfeminist signifiers, positioned in narratives designed to sell mass market children’s toys. In their respective work on animated and digitised animals, Paul Wells and Michael Lawrence point to the fallacy of dismissing animal animations as irrelevant or as innocuous child’s play. Wells suggests that animals are “an essential component of the language of animation” (2); so essential, in fact, that their presence has become a commonplace feature of these films and so naturalised as to be completely unremarkable. Lawrence clarifies the parallels between the digital manipulation of on-screen dogs and the history of dog breeding, writing “the exploitation of the dog’s ‘plasticity’ was dependent upon subjugating and subjecting real animals to the breeders’ ‘fantasy and will’” (119), and concluding that composite animal performances reveal “the repressed histories of such subjection” (120).

This article seeks to remedy the elision of the equine in discussions of the Brony fandom and attempts to understand what this community might be saying about horses and humans, particularly when it attempts to represent itself. These self-representations have become necessary because the Brony fandom has had to contend with an active anti-fandom. Anti-fans devote themselves to disparaging or parodying media texts; their impact has been traced in the work of Henry Jenkins, Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, Melissa Click and Matt Hills (Fan Cultures), among others. Writing on anti-fans of Fifty Shades of Grey, Sarah Harman and Bethan Jones argue that “anti-fans position themselves not only against and in opposition to the [texts] but also as superior to fans” (952).

In the case of the Bronies, anti-fans direct their hostility and ridicule exclusively toward the fans, deriding them as emotionally stunted, nonmasculine and socially inept men-children and aligning them with girl fans, whose desires are denigrated not merely by anti-fans but by discourses of fandom itself (Hills, “Get A Life”; Click). Exploring the gendered dynamics of anti-fandom in relation to MLP:FiM, Jones concludes that men and women anti-fans alike express rigid views of gender in their “Brony hate” posts on social media sites such as Reddit and 4chan (119). The conclusion that Brony haters are gender traditionalists implicitly supports another view that circulates through popular media and scholarly work including that of Robertson, Bell and Carey as well as that of Jon Anderson, writing on Bronies in the US military, that the most important and laudable aspect of the Brony fandom is its transgressive intervention in traditional modes of gender identification and differentiation.

In this narrative, Bronies courageously do battle with norms of gender and sexuality, in the face of online and face-to-face bullying, and should be embraced for their kinder, gentler version of masculinity. Robertson asserts that “the Brony community has embraced an identity that transgresses the stereotypical cynicism, hegemonic masculinity, and belligerence that tends to represent internet interactions” (33). According to Angela Watercutter, “their very existence breaks down stereotypes”.

Under this banner, and in response to its negative reception on the Internet and within broadcast media (notably on Fox News in the US), the fandom has undertaken a rebranding exercise, manifested in two documentary films: Brent Hodge’s A Brony Tale (2014), which screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2014, and Laurent Malaquais’s Kickstarter-funded BronyCon: The Documentary (2012), later retitled Bronies: The Extremely Unexpected Adult Fans of My Little Pony. This campaign overtly rejects the familiar model of fandom as dysfunction (Joli Jenson, “Fandom as Pathology”) and embraces a newer dispensation that links fandom with pedagogy (Hills, “Twilight Fans” 114). According to these two documentaries, Bronies teach us about nonpatriarchal modes of masculinity, using their respect and affection for and identification with the ponies of Equestria to help us all to become better people. The Brony fandom offers a unique and fascinating example of the intersection of online fandom, niche marketing, toy-based television series, and the gendering of childhood and adulthood. Intriguingly, the Bronies point to the way human aging can be gendered. Brony detractors conflate age and gender-inappropriate behaviour. If immaturity is viewed as a normative characteristic of women and fans, then perhaps only male fans can be defined as developmentally stunted.

Examining the Brony affection for the animated horse, I ask whether or not real horses have something to do with the Brony fandom and its rhetoric of self-representation. Despite the abstraction and ambiguity of animated animal figurations, we are never very far from the embodied, organic being-ness of the referent species, as Michael Lawrence, Paul Wells and Rebecca Miller (12) suggest. Animations speak to the assumptions we make about nonhuman animals and to our relationship to them. Just as horse DNA helped to structure the celluloid body of cinema (Shukin 91), the human-horse relationship, which is based historically upon humans being visually captivated by horses and harnessing them as vehicles of physical and spiritual transcendence, is enfolded within the lively dialogue and cutie marks of the My Little Pony franchise.

My desire to bring the equine aspects of the Brony fandom into relief is situated within a larger project that turns upon a claim I am making regarding a necessary relationship between horses and the moving image. This link is not only based on the animals’ material contribution to cinema’s celluloid matrix in the form of gelatine, but also on affective and perceptual responses to the size, physical proportions, speed and direction of movement of horses as well as on humans’ imaginative projections of horses as vehicles of physical and spiritual transport.

Film scholar Lynn Kirby argues for the inherently cinematic character of the train, asserting that the railroad, also known as the Iron Horse, should be understood as a protocinematic phenomenon. “As a machine of vision and an instrument for conquering space and time,” Kirby writes, “the train is a mechanical double for the cinema and for the transport of the spectator into fiction, fantasy and dream” (2). My proposition that horses are both necessary and central to cinematic representation does not contradict Kirby’s fascinating account of the mutual importance of railroad and cinema to modern visual culture. Instead, I suggest that we take a closer look at the possibility that horses—as organic engines, as animals on which humans have depended to traverse real and imagined spaces long before the modern era—laid the groundwork for the modes of pleasurable transport that we now associate with trains and with moving images.

Kirby persuasively links the modern industrial technology of the train with that of the silent cinema. I want to posit a pre-existing relationship between the equine species and cinema based on the horse’s size and proportions, rhythmic, linear motion and capacity for material and metaphorical transcendence. (Real and manufactured proportions are both relevant to this discussion, as Albrecht Dürer’s mathematical quest for the “ideal equine form” has played an important role in the visual aesthetics of the modern horse [Cuneo 120]). To put it in the terminology of the digital era, horses are to cinema what cats are to the Internet, although I am not yet prepared to fully define what that analogy encompasses. Perry Stein of The New Republic gathers together a cluster of arguments to explain the unanticipated dominance of cute cat memes and videos on the Internet, beginning with the fact that the human interest in cats extends back to the ninth century. Citing Michael Newell, Stein also argues that cat physiognomy is compelling because it reminds us of human children. Neither of Stein’s explanations accounts for the unique marriage of the feline and the Internet video form, however.

Stein cites the long history of the human–cat connection to establish a context for the feline-obsessed Internet. Using a similar logic, there is evidence that humans have worked with/exploited, looked at and sought to represent horses for a very long time. The domestication of the species dates back to 3500 BCE (Outram). Focusing on visual culture, the connection is far older. Cave paintings at Pech-Merle, Niaux and Chauvet, the latter made famous by Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), are between 14,000 and 35,000 years old and confirm that horses have held a particular intrigue for human visual artists for a very long time. The most prevalent animal depicted in French cave paintings are horses, despite the fact that the artists encountered a plethora of beasts in their daily lives, including bears, snakes and reindeer, which they hunted but did not paint. During a visit to Niaux in 2015, I witnessed a guide demonstrate the theory that the three dimensional paintings, which utilised projections of the rock for depth, could be made to appear to move, if a source of light such as a lantern or torch were to be waved in front of the wall. It’s easy to imagine that the humans who created these images of horses were early cineastes, captivated by the potential to make their images move like the animals they depicted.

The possibility that there is an organic link between the horse and the cinematic imagination remains speculative, and this work is informed by scholars pursuing different approaches to this question, such as Derek Bousé, who connects the history of the wildlife film to film itself (41), and Jonathan Burt, who considers animals to be the inspiration for cinema (210).

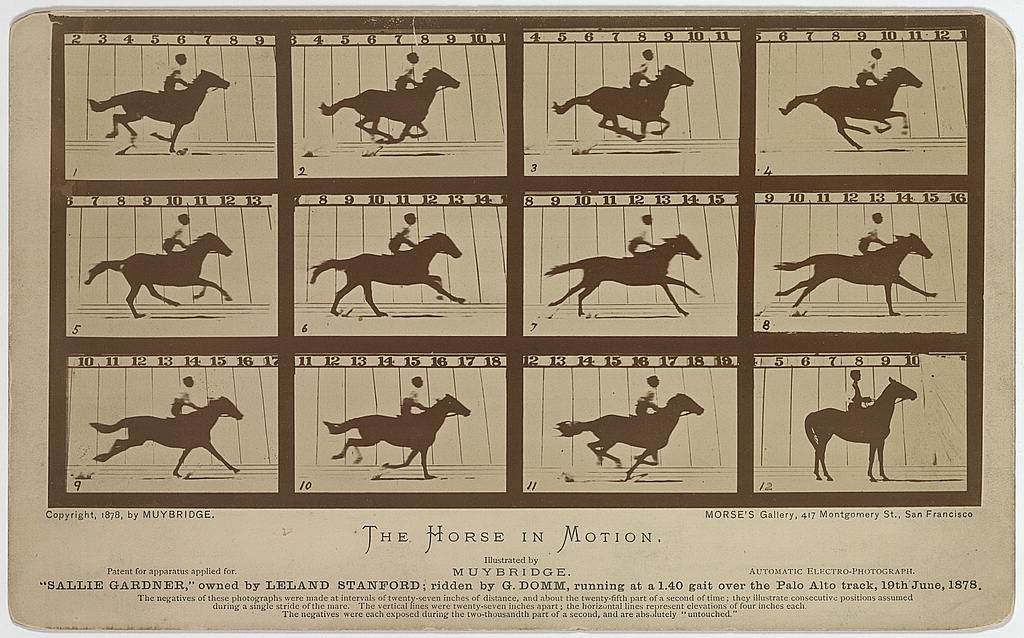

The fact that the horse was critical to the transition from static photography to moving images is well documented in the annals of film history. I would like, however, to interrogate the Palo Alto Stock Farm origin story: the familiar narrative that Leland Stanford’s wager about whether or not a galloping horse’s four hooves leave the ground at the same time led to the commissioning of a study by Eadweard Muybridge, whose serial photography experiments represent the “birth” of motion pictures. Setting aside the cave paintings, I specifically want to probe the story's aleatory elements by proposing that there might be deeper connections to horses rather than mere contingencies. Was it a coincidence, for example, that Stanford, a former governor but also a railroad magnate, sought to understand the movement of horses rather than that of another animal? John Ott links Stanford’s interest in equine locomotion to his financial interests in horse breeding and in railroads (“Iron Horses”); the anticipated profitability of these enterprises, along with the thrill of scientific discovery, must have played a role in the collaboration. But Arthur Knight reminds us that Stanford’s curiosity regarding the equine gait was generated during a period of illness in which his doctor prescribed a vacation. Stanford couldn’t travel and purchased a horse instead, a scenario that offers an instance of metonymic substitution (he couldn’t move, but the horses could) as well as a therapy modality (watching horses helped him recover).

Figure 2: “The Horse in Motion.” Sallie Gardner, owned by Leland Stanford. Palo Alto, CA, 19 June 1878. Eadweard Muybridge. Photographic print on card. US Library of Congress.

The man whom Stanford commissioned to experiment with his horses, Eadweard Muybridge, also came to the horse photography experiment after an illness, having suffered head injuries related to a stagecoach accident in 1860, after which his behaviour changed. This is the official story documented in Muybridge’s trial for the killing of the man he believed was his wife’s lover (Ball 243–59). Psychologist Arthur P. Shimamura speculates that lingering brain damage affected Muybridge’s ability to interact socially, as he was prone to emotional outbursts (350). Muybridge began his photography career after the accident, as his physician had counselled him to work outdoors (Shimamura 350). He first established a reputation as a landscape photographer, becoming famous for capturing the large, empty and static natural settings in which he would later deploy moving animals. Creating images of horse locomotion rehabilitated both Stanford and Muybridge and this therapeutic role of the horse finds a parallel in the (defensive) discourse of the Brony documentaries

The rhetoric of the Brony fandom has been marshalled in defence of its marginalised masculinity. Lauren Rae Orsini writes that Bronies are typically presented as “obsessive, Cheeto-chomping virgins” (Orsini, “Brony Psychology” 101). Bronies are seen as failed men. John Hawkins, writing for Right Wing News in 2012, complains:

Who’s responsible for these “men” failing as human beings and turning out to be complete losers who undoubtedly make everyone associated with them in any way feel completely ashamed? Is it liberal feminists, Barack Obama, some sort of heretofore undiscovered form of loser gene, crab men? It’s impossible to know for sure, but it’s completely appalling to see people who think of themselves as “men” behaving like this.

A 2012 CollegeHumor video entitled “My Little Brony: Friendship is Tragic,” which has racked up more than five million hits on YouTube, humorously reiterates these stereotypes from the perspective of the MLP:FiM characters, invoking a toy collector with Cheetos, a five o’clock shadow, inadequate social skills, an online Korean girlfriend (a double-edged and problematic trope in itself) and unusual sexual practices involving toys, fan fiction and flashlights.

Figures 3 and 4: Pinky Pie and Twilight Sparkle find themselves captives of a stereotypical, Cheeto-eating Brony (left); and Twilight Sparkle is the unwilling object of adult Brony affection (and unkempt stubble) (right) in the Funny Or Die parody “My Little Brony: Friendship is Tragic”. CollegeHumor, 2012. Screenshots.

And, indeed, one recurring concern that the Brony fandom constantly polices is the potential for eroticisation of children’s toys, children’s programming and, by extension, children themselves. Images of MLP:FiM blow-up dolls and plushies—some of them made by Bronies themselves as part of the creativity licensed and encouraged by this “participatory” fandom (Jenkins)—met with anxiety when publicised on the Internet. Bronies engage in a wide range of prosumer practices as they create familiar outputs such as fan fiction, artwork, music and laser light shows at Bronycon and also go farther, to “rework biblical narratives using characters and images from MLP: FIM” (Crome 400). Bronies, like many fan communities in convergent media culture take seriously the promise of fandom as a “permanent outlet for their creative expression” (Jenkins 42).

Some forms of that creative expression are decidedly controversial. In January 2015, the Huffington Post published David Moya’s piece: “Inflatable Life-Size ‘My Little Pony’ Doll Arousing Controversy With Bronies (NSFW)”, which describes a 5’9” “Sexy Inflatable Girl Pony” made in China by Hongyi Toy Manufacturing. The article quotes an unattributed source as saying: “And this is why I’m slowly regretting becoming a Brony, this community is just delving deeper and deeper into the disgusting” (qtd. in Moya).

Showing similar creative chops, UK artist Hoppip created a plushie sex toy from a minor character named Lyra Heartstrings and auctioned it off on the Dealer’s Den web site with a surprisingly literal tag line: “This is the very first MLP plushie to feature a special hole in her butt that you can stick your penis in” (qtd. in Orsini, “Sexually Functional”). The need for such directives suggests that, at least in the eyes of the manufacturer, the target demographic for this product may require careful instruction as to the “appropriate” inappropriate sexual behaviour.

In response to the negative perceptions generated by the press—especially Fox News, whose incredulous and mocking attacks, beginning with Bill Kristol’s on “Red Eye on ‘Bronies’”, aired on 17 June 2011, have been uploaded to YouTube by Bronies and their allies—Bronies have taken matters into their own hands. James Turner of New Hampshire sought to raise $2,000 on IndieGoGo but raised $14,000 instead to fund a video to run on MLP:FiM network The Hub in order to thank the programme’s creators.

In revamping their image, the Bronies have returned to an older media form—documentary film—which is also a recognised platform for advocacy. The two films, Hodge’s A Brony Tale and Malaquais’s Bronies: The Extremely Unexpected Adult Fans of My Little Pony promulgate a strongly sympathetic view of a tame Brony herd. The films link MLP:FiM exclusively to young men and adolescent boys with an anti-cynicism ethos and a New Sincerity sensibility. Any whiff of adult Bronies or sexual perversity is suppressed. In Bronies, an animated professorial horse instructs the audience in a typology of Bronies; when he mentions “clopping”—the practice of masturbating using MLP:FiM programmes and paraphernalia—he stops, flummoxed before his class of innocent students, and immediately moves on, never defining the term or returning to that subject.

Both films are narratively invested in telling the stories of awkward young men who find acceptance at Brony conventions. They offer glimpses of MLP:FiM creator Lauren Faust as well as voice actors Ashleigh Ball and John De Lancie as they come to terms with their Brony fans. Ball, who initially expresses misgivings, learns that Bronies are nothing more than geeky, loveable non-threatening boys. John De Lancie, who provides the voice of the character Discord on MLP:FiM, indicated his motivations for helping to produce the Bronies film at the Ottawa ComiCon on 13 May 2012. A YouTube clip records his statement:

I was really taken aback by how disrespectful a couple of things were said [sic] about the community on national news… I’ve decided to do it in a way that I think is the right way. So I think I’m going to be entering further into that world. (“John De Lancie Announces”)

After Faust signed on, the film became the second-highest funded film on Kickstarter, with over $300,000 in pledges, according to De Lancie’s website.

In A Brony Tale, Ashleigh Ball, who voices the characters of AppleJack and Rainbow Dash, admits to her discomfort with her own fans: “You see a guy that’s wearing a pony outfit and you’re like ‘That’s weird. I don’t know about that. That makes me uncomfortable’.” By the end of the film, her interactions with cheering young men have allayed her concerns.

The two documentaries are highly sympathetic texts that subscribe to the dictum that the best defence is a good offence. In them, thevoice actors learn to stop worrying and love the Brony fandom; fathers of Bronies learn to accept their sons’ unconventional choices, and Bronies themselves learn to navigate anxious social situations. In one poignant narrative in Bronies, which follows several young men who live in North Carolina, Maine, Israel and England as they make their respective pilgrimages to BronyCon, Daniel Richards, a young man from Rugeley near Manchester, England, discloses his Asperger’s diagnosis. For him, Asperger’s means “not understanding people’s emotions”: text superimposed on the screen defines the condition as making people “difficult with social interactions”. At one point, prior to embarking on his much anticipated and emotionally freighted solo journey to BronyCon, Daniel visits some horses in a field and thus forges a link between real animals and the comfort he derives from his fandom:

Animals I find much more like easier when I’m trying to relax or cool down from talking with a lot of people. They don’t have any demands … any major emotional demands anyway, so I feel like they’re much easier to understand, interact with.

Figure 5: Daniel finds comfort interacting with horses. Bronies: The Extremely Unexpected Adult Fans of My Little Pony (Laurent Malaquais, 2012). BronyDoc, LLC, 2013. Screenshot.

Later, on his way to BronyCon, he loses his bearings and becomes anxious; the scene is quite tense, as Daniel clearly doesn’t know how to approach a stranger to ask for directions. Near its conclusion, however, the film depicts Daniel at the centre of a circle of young men giving one another the Brony equivalent of a high five, the brohoof. In voiceover, he shares the joy of that experience and also conveys his belief that the BronyCon experience, which forced him outside his comfort zone, has made him far less socially anxious. Through literal and metaphorical acts of transportation—on a train to BronCon and through his affection for the ponies of MLP:FiM—Daniel finds an accepting Brony community, and perhaps even a wider world; groups of people that have become more like the living horses in the field with whom he found it comfortable to interact. Daniel’s narrative, along with that of Lyle, a young Maine boy whose stern and uncomprehending father begrudgingly agrees to watch some episodes of MLP:FiM after attending the convention, helps to shape the film’s resolution as a heart-warming tale of lonely boys saved by a loving, like-minded Brony community.

Figures 6 and 7: Daniel (with his back to the camera) orchestrates a massive brohoof; and Daniel happily recounts his experiences at Bronycon. Bronies: The Extremely Unexpected Adult Fans of My Little Pony. BronyDoc, LLC, 2013. Screenshot.

In its characterisations of itself in the documentaries, and in the Wofford College Research project (Brony Study), the fandom inherits several strands of boyhood culture from the past several decades: the geek charm of Star Wars fandom, Harry Potter’s magical coming of age narratives and the much-ballyhooed gender fluidity associated with Carol Clover’s influential analysis of male horror fans in Men, Women and Chainsaws. In short, the Brony fandom has embraced a position within the potent dialectic of masculine vulnerability. Whereas some Brony commentary points to the anxiety of post 9-11 culture in general as a factor explaining the desire for cuddly safety (Lambert), there is a different case to be made, one that points to antifeminist discourses around masculinity and disability as one key to the Brony fandom. These discourses return us to the matter of equine therapy and underscore the connections between horses, movement and cinema.

This therapeutic mode of fandom echoes the one theorised by Camille Bacon-Smith in the “Training New Members” chapter of her pathbreaking study on Star Trek fan fiction, Enterprising Women. Bacon-Smith writes that women attempt to renegotiate patriarchal gender norms by “[talking] to each other about themselves in the symbolic language of their literature” (156). In the documentaries, Bronies are indeed talking about themselves, but the fact of their talk therapy is less important than the terminology used, which resonates with a chorus of lament that has emerged in popular self-help culture regarding the state of contemporary masculinity.

The Brony phenomenon must be contextualised within the re-emergence of a culture of gender-distinct childhood during a historical period (particularly in the US) in which feminist gains have come to be understood as not only empowering girls, but also as disadvantaging boys. Recent scholarship and journalism on the pathologisation of childhood misbehaviour has been informed by an antifeminist agenda. A 2014 Esquire Magazine feature entitled “The Drugging of the American Boy” draws extensively from the work of Ned Hallowell, a psychiatrist diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) whose books include Driven to Distraction and Delivered from Distraction. The article reports that “by High School, nearly 20% of all boys will have been diagnosed with ADHD—a 37% increase since 2003”. Hallowell claims that the US is pathologising boyhood in part through the “girlification” of elementary school (D’Agostino). Hallowell is joined in this venture by Philip Zimbardo, of the famed Stanford Prison experiment, who has published The Demise of Guys: Why Boys Are Struggling and What We Can Do About It and Man Disconnected: How Technology Has Sabotaged What It Means to be Male with Nikita D. Coulombe. These two manifestos (and a related TED talk) blame video games, porn and workforce gains by women for the failures of boys in school and in relationships. Sociologists who have written on the “the medicalization of childhood deviance” (Hart, Grand, and Riley 132) characterise ADHD as a construct that originates within the white middle class in the US, a group experiencing a decades-long decline in the resources (largely, unpaid female domestic labour) available for dealing with childhood “deviance”.

In this wider context, the celebration of the Brony fandom has been achieved in part through a reframing of masculinity as disability (with boys the victim of feminist gains) and through the appropriation of therapeutic discourses aimed at remedying the situation. In this regard, MLP:FiM’s anthropomorphic creatures are no coincidence: it matters that they are animals and horses. The case championing the Bronies is linked to the growth of not just animal-assisted therapy for a host of human ills—comfort dogs to lower blood pressure, for example—but to equine-assisted therapy (EAT) for children diagnosed with ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a disorder for which boys are diagnosed at a rate four and a half times that of girls. According to Edwards and Redden’s Brony Study, the community it surveyed reported a high incidence of social anxiety-related disorders. Among those disclosing a diagnosis, 28.3% reported depression, 23.3% reported ADHD/ADD, 22% anxiety and 14.6 % Asperger’s.

The posited benefits of EAT, rather than Animal Assisted Therapy, in children with ADHD and ASD is that riding horses helps them to focus and addresses social anxiety (Equine Therapy; Malcolm; van den Hout et al.). Practitioners posit that the horse’s dance-like movements—movements I would characterise as central to the horse’s capacity for various modes of transport and transcendence—compensate for the neural underconnectivity and lower cortisol levels for children with ASD and anxiety (Pendry et al.). The documentary The Horse Boy (Michael Orion Scott, 2009), based on the book of the same name by Rupert Isaacson, details the EAT method Isaacson developed with his son Rowan and eventually expanded into the “Horse Boy method”, a therapy now offered in conjunction with the University of Texas, where its effects are being studied by educational psychologist Jennifer Anne Lockwood. The theorised therapeutic pathway relates to the way the horse’s rhythms produce oxytocin, calming anxiety. Issacson eventually taught his son to read books while on horseback, believing that he could focus better while riding. Those involved in EAT draw upon the horse’s material and metaphysical capacities for transportation, as the horse helps the children to navigate and negotiate the relationship between the self and the world.

Brony Luke Allen makes a connection between his Asperger’s diagnosis and Brony fandom in an article published in Psychology Today:

This weird alchemy that Lauren Faust tapped into when she set out to make the show accessible to kids and their parents hooks into the male geek’s reptilian hindbrain and removes a lifetime’s behavioural indoctrination against pink. As a person with Asperger’s syndrome, I learned more about theory of mind, friendships and social interactions from this season (of MLP) than I had in the previous 31 years of life. (Qtd. in Griffiths)

As the Brony fandom attempts to champion its members as progressive gender nonconformists while neutralising the sexual threat of adult males identifying with animated ponies and their young girl fans as well as viewing the ponies and girls as objects of sexual desire, the characterisation of adolescent Bronies as a vulnerable population, potentially disabled by their masculinity in a feminist world, resonates with a broad cultural alarmism concerning the academic and social performance of young boys. The connection between the animated ponies that Bronies use to “self-medicate” (to pursue the therapeutic discourse) and the real horses conscripted for human therapeutic purposes relates to the unique importance attributed to the horse’s organic, rhythmic motion and its purported benefits for children with ADHD, ASD, anxiety, and Asperger’s. In this linkage, the horse is recognised as moving humans physically, emotionally and spiritually—moving them beyond their limited frame of reference to new and other worlds, which is the equine capacity that I would define as essentially cinematic.

The case of the Brony fandom thus raises numerous aesthetic, cinematic and cultural issues that extend beyond its putative challenge to gender normativity. I have argued here that it is not coincidental that horses, both real and animated, occupy centre stage within the melodrama of contemporary masculinity and its expression within moving image culture. Horses have been treated as organic machines that enable human work of all kinds (including emotional work) and provoke imaginative flights of fancy; they are understood to possess empathetic qualities that make them useful to humans who are lacking in those attributes. Thus they remain subject to varied practices and projections of humans through the aesthetics of the moving image and the fandoms spawned by those images.

References

1. Anderson, Jon.“Bronies in uniform—and proud of it.” Navy Times. 30 Aug. 2012. Gannett Co., Inc. Web. 24 Aug. 2015. <http://archive.navytimes.com/article/20120830/OFFDUTY02/208300304/Bronies-uniform-proud-it>.

2. Bacon-Smith, Camille. “Training New Members.” Fan Fiction Studies Reader. Ed. Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2014.138–58. Print.

3. Ball, Edward. The Inventor and the Tycoon: A Gilded Age Murder and the Birth of Moving Pictures. New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2013. Print.

4. Bass, Margaret, Maria M. Llabre, and Catherine A. Duchowny. “The Effect of Therapeutic Horseback Riding on Social Functioning in Children with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39.9 (2009): 1261–68. Print.

5. Bell, Christopher. “The Ballad of Derpy Hooves: Transgressive Fandom in My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic.” Humanities Directory 1.1 (2013): 5–22. Print.

6. Bousé, Derek. Wildlife Films. Philadelphia, PA: U Pennsylvania P, 2000. Print.

7. Brony Study (Research Project). Edwards, Patrick, and Marsha Redden. 2013. Web. 12 Nov. 2014. <http://www.bronystudy.com/>.

8. Buck, Chris and Jennifer Lee. Frozen. Walt Disney Studios, 2013. Film.

9. Burt, Jonathan. “The Illumination of the Animal Kingdom: The Role of Light and Electricity in Animal Representation.” Society & Animals 9.3 (2001): 203–28. Print.

10. Carey, Maria Helena. My Little Brony Project: Tolerance is Magic. MA Diss. Corcoran College of Art and Design, 2014. ProQuest: UMI Dissertations Publishing. PDF file.

11. Click, Melissa. “‘Rabid,’ ‘Obsessed,’ and ‘Frenzied’: Understanding Twilight Fangirls and the Gendered Politics of Fandom.” Flow 11.04, 18 Dec. 2009. Web. 22 June 2015. <http://www.flowtv.org/>.

12. Clover, Carol. Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1992. Print.

13. Crome, Andrew. “Reconsidering Religion and Fandom: Christian Fan Works in the My Little Pony Fandom.” Culture and Religion 14:4 (2014), 399–418. Print.

14. Cuneo, Pia F. “His Horse, A Print, and Its Audience.” The Essential Dürer. Ed. Larry Silver and Jeffrey Chips Smith. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2011. 115–29. Print.

15. De Lancie, John. “BronyCon: The Documentary.” 11 June 2010. Web. 22 June 2015. <http://delancie.com/2012/06/11/bronycon-the-documentary/>.

16. Driscoll, Catherine, and Melissa Gregg. “Convergence Culture and the Legacy of Feminist Cultural Studies.” Cultural Studies 25.4–5 (2011): 566–84. Print.

17. D’Agostino, Ryan. “The Drugging of the American Boy.” Esquire Magazine. 27 Mar. 2014. Print.

18. Equine Therapy: Animal Assisted Therapy. Web. 26 Jan 2015. <http://www.equine-therapy-programs.com/therapy.html>.

19. Gray, Jonathan. “New Audiences, New Textualities: Anti-fans and Non-fans.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 6.1 (2003): 64–81. Print.

20. Griffiths, Mark D. “Pony Play Station.” Psychology Today. 14 July 2014. Web. 25 June 2015. <https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-excess/201407/pony-play-station>.

21. Hallowell, Ned and John J. Ratey. Delivered from Distraction: Getting the Most of Life with Attention Deficit Disorder. New York: Ballantine Books, 2005. Print.

22. ---. Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping with Attention Deficit Disorder from Childhood Through Adulthood. New York: Touchstone, 1995. Print.

23. Harman, Sarah, and Bethan Jones. “Fifty Shades of Ghey: Snark Fandom and the Figure of the Anti-fan.” Sexualities 16.8 (2013): 951–68. Print.

24. Hart, Nicky, Noah Grand, and Kevin Riley. “Making the Grade: The Gender Gap, ADHD, and the Medicalization of Boyhood.” Medicalized Masculinities. Ed. Dana Rosenfeld and Christopher Faircloth. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2006. 132–64. Print.

25. Hawkins, John. “Horror You Will Never Get Out of Your Head: Bronies.” Right Wing News. 26 Apr. 2012. Web. 4 Apr. 2015. <http://www.rightwingnews.com>.

26. Herzog, Werner. Cave of Forgotten Dreams. IFC Films, 2011. Film.

27. Hills, Matt. “Negative Fan Stereotypes (‘Get a Life!’) and Positive Fan Injunctions (‘Everyone’s Got To Be a Fan of Something!’): Returning To Hegemony Theory in Fan Studies.” Get a Life?: Fan Cultures and Contemporary Television. Spec. issue of Spectator 25:1 (2005): 35–47. Print.

28. ---. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

29. ---. “Twilight Fans Represented in Commercial Paratexts and Inter-Fandoms:Resisting and Repurposing Negative Fan Stereotypes.” Genre, Reception, and Adaptation in the Twilight Series. Ed. Anne Morey. London: Ashgate, 2012. 113–29. Print.

30. Hodge, Brent. A Brony Tale. Hodgee Films, 2014. Film.

31. Isaacson, Rupert. The Horse Boy: A Father’s Miraculous Journey to Heal His Son. New York: Penguin, 2009. Print.

32. James, E.L. Fifty Shades of Grey. London: Vintage Books, 2011. Print.

33. Jenkins, Henry. “Textual Poachers.” Fan Fiction Studies Reader. Ed. Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2014. 26–44. Print.

34. Jenson, Joli. Convergence Culture. New York: New York UP, 2006. Print.

35. ---. Fandom as Pathology: the Consequences of Characterization.” The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media. Ed. Lisa A. Lewis. New York: Routledge, 2002. 9–29. Print.

36. “John De Lancie Announces Brony Documentary” (Ottawa Comicon). YouTube. 13 May 2012. Web. 26 June 2015. <https://youtu.be/HVK3jgOhFwY>.

37. Jones, Bethan. “My Little Pony, Tolerance is Magic: Gender Policing and Brony Anti-fandom.” Journal of Popular Television 3.1 (2015): 119–25. Print.

38. Kearney, Mary Celeste. “Sparkle: Luminosity and Post-Girl Power Media.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 25 (2015). 1–11. Print.

39. Kirby, Lynn. Parallel Tracks: the Railroad and Silent Cinema. Durham: Duke UP, 1997. Print.

40. Knight, Arthur. Eadweard Muybridge: The Stanford Years, 1872–1882. Palo Alto: Stanford University, 1971. Exhibition Catalogue. 7 Nov. 2012. Web. 25 June 2015. <https://archive.org/details/eadweardmuybridg00maye>.

41. Labash, Matt. “The Dread Pony.” Weekly Standard. 26 Aug. 2013. 10–12. Print.

42. Lambert, Molly. “The Internet Is Magic: Exploring the Wonderful World of My Little Pony Fandom in Bronies.” Grantland. 12 Nov 2013. Web. 25 July 2015. <http://grantland.com/hollywood-prospectus/the-internet-is-magic-exploring-the-wonderful-world-of-my-little-pony-fandom-in-bronies/>.

43. Lawrence, Michael. “‘Practically Infinite Manipulability’: Domestic Dogs, Canine Performance and Digital Cinema.” Screen 56.1 (2015): 115–20. Print.

44. Malaquais, Laurent. Bronies: The Extremely Unexpected Adult Fans of My Little Pony. 2012. BronyDoc, LLC, 2013. DVD.

45. Malcolm, Lynne. “Autism, Horses and Other Therapies.” All in the Mind. Australian Broadcast Corporation. 19 Oct. 2014. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. <http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/allinthemind/autism2c-horses-and-other-therapies/5809256>.

46. Mendelsohn, Tom. “Zoe Quinn and the Orchestrated Campaign of Harassment from Some ‘Gamers’.” The Independent 5 Sept. 2014. Web. 22 June 2015. <http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/zoe-quinn-and-the-orchestrated-campaign-of-harassment-from-some-gamers-9715427.html>.

47. Michaels, Sean. “Taking the Rick.” The Guardian 27 July 2008. Web. 2 Apr. 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/mar/19/news>.

48. Miller, Rebecca Erin. The Animated Animal: Aesthetics, Performance and Environmentalism in American Feature Animation. Diss. New York University, 2011. ProQuest: UMI Dissertations Publishing. PDF file.

49. Morpurgo, Michael. War Horse. London: Kaye and Ward, 1982. Print.

50. Moya, David. “Inflatable Life-Size ‘My Little Pony’ Doll Arousing Controversy With Bronies (NSFW).” Huffington Post. 21 Jan 2015. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/21/inflatable-lifesize-my-li_n_6511712.html>.

51. “My Little Brony: Friendship is Tragic.” College Humor Animation. YouTube. 13 Apr 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. <https://youtu.be/2p6LVZFLSfw>.

52. My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic. Prod. Lauren Faust. Hub Network (2010–14) and Discovery Family (2015–present). Television.

53. Orsini, Lauren Rae. “Brony Psychology 101: What 2 Researchers Discovered.” The Daily Dot. 12 July 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. <http://www.dailydot.com/society/my-little-pony-brony-study-results/>.

54. ---. “Sexually functional ‘My Little Pony’ Toy Inspires Fan Following.” The Daily Dot. 31 May 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. <http://www.dailydot.com/society/my-little-pony-brony-sex-toy/>.

55. Ott, John. “Iron Horses: Leland Stanford, Eadweard Muybridge, and the Industrialised Eye.” Oxford Art Journal 28.3 (2005): 409–28. Print.

56. Outram, Alan K., Natalie A. Stear, Robin Bendrey, Sandra Olsen, Alexei Kasparov, Victor Zaibert, Nick Thorpe, and Richard P. Evershed. “The Earliest Horse Harnessing and Milking.” Science. 323.5919 (6 Mar. 2009) 1332–35. Print.

57. Pendry, Patricia, Annelise N. Smith, and Stephanie M. Roeter. “Randomized Trial Examines Effects of Equine Facilitated Learning on Adolescents’ Basal Cortisol Levels.” Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin 2.1 (2014): 80–96. Print.

58. The Powerpuff Girls. Exec. Prod. Craig McCracken. Cartoon Network. 1998–2005. Television.

59. Pramaggiore, Maria. “The Celtic Tiger’s Equine Imaginary.” Representing Animals in Irish Literature and Culture. Ed. Kathryn Kirkpatrick and Borbala Farago. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015. 270–91. Print.

60. “Red Eye on ‘Bronies’.” Fox News. YouTube. 17 June 2011. Web. 1 Dec. 2014. <https://youtu.be/fi27530dDCc>.

61. Robertson, Venetia Laura Delano. “Of Ponies and Men: My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic and the Brony Fandom.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 17.1 (2014): 21–37. Print.

62. Sandvoss, Cornel. Fans: The Mirror of Consumption. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005. Print.

63. Scott, Michael Orion. The Horse Boy. Horse Boy Foundation, 2009. Film.

64. Shimamura, A. P. “Muybridge in Motion: Travels in Art, Psychology, and Neurology.” History of Photography, 26 (2002): 341–50. Print.

65. Shukin, Nicole. Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 2009. Print.

66. SpongeBob SquarePants. United Plankton Pictures and Nickelodeon Animation Studios. 2008–present. Television.

67. Stein, Perry. “Why do Cats Run the Internet?” The New Republic. 2 March 2012. Web. 26 June 2015. <http://www.newrepublic.com/article/politics/101283/cats-internet-memes-science-aesthetics>.

68. Swift, Jonathan. Gulliver’s Travels: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Ed. Christopher Fox. Boston: Bedford Books, 1995. Print.

69. van den Hout, C.M.A., and S. Bragonje. “The Effect of Equine Assisted Therapy in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” MSc Diss. Vrije Universiteit. Faculty of Human Movement Sciences. 30 June 2012. Print.

70. Watercutter A. “Bronies are Redefining Fandom: and American Manhood.” Wired Online. 11 Mar. 2014. Web. 12 Apr. 2015. <http://www.wired.com/2014/03/bronies-online-fandom>.

71. Wells, Paul. 2008. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP. Print.

72. “You’ll Play Your Part.” From “Twilight’s Kingdom Part 1.” My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic Season 4 Episode 25. YouTube. 10 May 2014. Web. 15 Aug. 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4auA36FMAto>.

73. Zimbardo, Philip and Nikita Coulombe. Man Disconnected: How Technology has Sabotaged What It Means to be Male. New York: Ryder Books, 2015. Print.

74. ---. The Demise of Guys: Why Boys Are Struggling and What We Can Do About It. Amazon Digital Services, 2012. E-book.

75. ---. “The Demise of Guys”. TED Talk. Mar. 2011. Web. 27 Jul 2015. <http://ed.ted.com/lessons/philip-zimbardo-the-demise-of-guys>.

Suggested Citation

Pramaggiore, M. (2015) 'The taming of the Bronies: animals, autism and fandom as therapeutic performance', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 9, pp. 6–22. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.9.01.

Maria Pramaggiore is Professor and Head of Media Studies at Maynooth University in Kildare, Ireland. Her most recent book is Making Time in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon: Art, History & Empire (Bloomsbury 2014). She is currently co-editing a book on the voice in documentary with Bella Honess Roe and writing a monograph on the horse in modern visual culture.