Lindsay Anderson: Britishness and National Cinemas

Isabelle Gourdin-Sangouard

Throughout his career, Lindsay Anderson maintained a highly adversarial relationship with the British film industry. First as a film critic and subsequently as a film director, he deemed the environment in which films were produced and received in Britain to be hostile to a viable industry both in artistic and economic terms. Conversely, the issue of Britishness became an asset for Anderson when his films reached the international scene: as early as 1954, he received an Oscar with Guy Brenton, a fellow Oxford graduate, for Thursday’s Children (1953), a documentary short. Similarly, in 1969, If…. (1968) was awarded the Palme D’Or at the Cannes International Film Festival.

This article will explore three key stages in Anderson’s career that illustrate the complex relationship between the director’s negotiation of his own national background and the imposition of a national identity in the critical reception of his work. First, I will look briefly at Anderson’s early directorial career as a documentary filmmaker: by using references to the Free Cinema movement and Thursday’s Children, I will show that, in both instances, the question of artistic impact and critical reception took on a transnational dimension. I will then discuss the production of a documentary short in Poland, which Anderson filmed at the request of the Documentary Studio in Warsaw in 1967, and which constitutes the director’s first experience of working in a foreign film industry. Finally, I will discuss Britannia Hospital (1982), the last feature film that Anderson made in Britain. Throughout the paper, I will also use material from the Lindsay Anderson Archive held at Stirling University.[1]

The Artist and the Nation

The notion of national identity resonates distinctively throughout Anderson’s career. In an interview with Paul Ryan, who edited his writings in the early 1990s, Anderson defines himself as “a child of the British Empire” (Anderson, “Child of Empire” 35). He had previously used the phrase in an article that he wrote in 1988 for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine, in which he presented his family history as the determining factor in his lack of a clearly defined sense of national identity and the resulting impact that this had had upon his career:

My father, a Scot and a soldier, was born in Nassik, North India. My mother (born in Queenstown, South Africa) was a Bell. I was born in Bangalore, a child of Empire. Did these antecedents make for an alienation, long unrecognised? (Anderson, “My Country” 33)

Anderson sees his early love of the arts—here, theatre and cinema—as indicative of a “[v]ery un-English” personality (34). He uses these very words in the article in order to stress the extent of the gulf that separates him from his fellow country men and women. Anderson describes his character as impulsive and driven by an absolute belief in the value of commitment—intellectual or otherwise (34)—which in his opinion, places him at odds with the cultural consensus over the place of the artist in English society. I use the word “English” here as opposed to “British”in keeping with Anderson’s choice to exclude any other adjective that would refer to Britain in its entirety. In fact, he assimilates the two—English and British—at the end of his article, thereby relating the British nation as a whole to the cultural model he explicitly defines as English (34). In other words, Anderson equates the political entity known as Britain with what he perceives to underpin the essence of English culture: a patronising attitude towards the arts and an inability to do away with the class system (34). The resulting definition of the national character rests upon the pairing on unequal terms of one cultural model with the political entity it is a part of. It follows that the concept of national identity for Anderson becomes intrinsically linked with Britain’s treatment of the arts and, by implication, the artist.

An unexpected win at the Academy Awards in Hollywood for Best Documentary Short in 1954 proved for Anderson the first instance of a confrontation between different national perspectives over his work. In this instance, the American recognition of the value of Thursday’s Children contrasted strongly with the indifference with which the work had been met in Britain.[2] The Oscar was awarded for a documentary about the everyday life and education of deaf children at a school in Margate in South East England. Anderson shot the documentary with Guy Brenton, in 1953.

Thursday’s Children (1953): a lesson at the Royal School for Deaf Children in Margate. Source: Lindsay Anderson Archive, University of Stirling.

While shooting Thursday’s Children, Anderson also filmed a short documentary of his own in a nearby amusement park. Although Anderson enlisted the help of the cameraman John Fletcher for the filming, O Dreamland (1953) remains a personal initiative as he made all of the creative decisions, including the editing of the footage, and self-financed it (Anderson, “Finding” 60). The short film did not generate much interest nationally (60). The situation changed dramatically when Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson decided to group their films together and show them at the National Film Theatre in London (Anderson, “Free Cinema” 74; Anderson, “Every Day” 70; Sussex 30-1). O Dreamland constitutes the first true instance for the director of a convergence between a personal vision and established professional connections, which enabled the project to come to fruition by allowing for the possibility of both critical appraisal and public scrutiny. These occurred both at a national and transnational level.

O Dreamland (1953): Margate fun fair—footage. Source: Lindsay Anderson Archive, University of Stirling.

Free Cinema and Transnationalism

Free Cinema is a label—“a peg” in Anderson’s words (Anderson, “Every Day” 70)—applied to a group of documentary shorts made by a group of young aspiring filmmakers in the mid-fifties. Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson wanted to make films; however, none of them was a member of the British film industry’s technicians’ union (ACTT, Association of Cinematograph Television and Allied Technicians), or linked with a British studio (Anderson, “Starting” 54). They decided to join forces and grouped their shorts into a single programme, prefaced by a manifesto outlining their objectives as documentary filmmakers (Anderson, “Free Cinema” 74; Anderson, “Sequence” 47; Anderson, “ Every Day” 70; Sussex 30-1). Reisz was in charge of programming at the National Film Theatre at the time, which guaranteed a screening of their shorts at the cinema. The resounding success with which their initiative was met secured a further five Free Cinema programmes until 1959.

Matt McCarthy, a filmmaker who had once been technical officer of the British Film Institute, contributed an article on Free Cinema to the British journal Films and Filming in 1959, in which he connects the question of technical expertise with that of national identity in film. His overall argument highlights the centrality of film technique in the assessment of the artistic impact that a film has in a given national context; most especially in a British one, which, as I will develop at a later stage, impacted on Anderson’s assessment of British cinema in relation to his own work. In McCarthy’s opinion, the movement missed an opportunity to enrich British cinema by depriving it of its “voice”:

Perfection must be the aim, mastery of the medium, and pride in craftsmanship. They are vital to the development of every art form, and can alone grant the British film-makers the eloquence they lack. (17)

McCarthy’s verdict does not, however, express a consensus over the legacy of Free Cinema: The Times, for instance, showed a high degree of enthusiasm for the initiative and covered each programme shown at the National Film Theatre. When the Free Cinema movement disbanded in 1959, the newspaper provided a comprehensive overview of its impact abroad (The Times, “End of a Movement” 13). It argued that the experiment had inspired similar initiatives—in the United States, notably—that testified to the vitality of young British filmmakers and further vouched for the cultural validity of the project (The Times, “End of a Movement” 13; “Progress of Free Cinema” 3).

These contrasting views bring out one key feature of Free Cinema: by allowing the contributors complete creative freedom—both in terms of style and content—the movement offered a template for a transnational, transcultural approach to filmmaking. In other words, The Times’s appraisal illustrates the extent to which the movement managed to operate outside of the artistic and technical framework provided by the national film industry, thereby suggesting new criteria to evaluate the value of their work. This can be summed up in Richardson’s contribution to the Free Cinema manifesto—“Perfection is not an aim” (qtd. in Sussex, 31)—to which McCarthy undoubtedly was referring in his article.

The 1957 programme, Free Cinema 4, entitled “Look at Britain!”, which included a documentary made by Swiss filmmakers Claude Goretta and Alain Tanner and a short film written and co-directed by Lorenza Mazzetti, an Italian artist, captures the spirit of the artistic endeavour. The three Free Cinema programmes that followed until March 1959 constitute a good example of the propensity for the movement to reach a transnational dimension. In September 1958, two programmes were screened in rapid succession at the National Film Theatre: the first showcased recently produced shorts from Poland, including Roman Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe (Dwaj ludzie z szafa, 1957). The second, entitled French Renewal, presented for the first time in Britain, the works of two representatives of the French New Wave, François Truffaut’s Les Mistons (Brats, 1957) and Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge (1958). A letter that Anderson wrote to Truffaut after the screening of Les Mistons brings out the creative and liberating dimension that the initiative acquired for the filmmakers involved:

LES MISTONS/BRATS has been well received. With great warmth, and I believe that the movement CAHIERS-CINEASTES is off to a great start here in England … It’s really fantastic what you’ve been doing—you and your fellow film directors—in France. And so important. In this country with a moribund cinema it all seems miraculous. [sic] (Anderson “Letter Truffaut”) [3]

Anderson’s comment about the state of the British film industry highlights the impact that the tension between the artistic and the national had on his work. In his opinion, a distinct cultural vision can be either supported or hampered by the national context in which it originates. O Dreamland constitutes a manifestation of this tension: with distinct echoes of Humphrey Jennings’s Spare Time (1939) and Jean Vigo’s À propos de Nice (1930), Anderson’s first contribution to the Free Cinema movement both acknowledges a sense of national legacy and a willingness to transcend it. An article published in The Times on the occasion of the short’s screening at the National Film Theatre shows an awareness of the nature of the artistic fabric underpinning O Dreamland: it suggests that the cultural subtext both derives from and undermines the stamp of the national that the Documentary Movement of the 1930s exemplifies (See The Times, “The Personal Approach” 10).[4]

A Transnational Experience: Miroslav Ondříček and The White Bus

Roughly twenty years before he made The Whales of August (1987) and Glory! Glory! (1989),[5] Anderson filmed Raz, dwa, trzy (The Singing Lesson,1967) in Poland at the invitation of the documentary studio in Warsaw (LA 1/05/5/1; Sussex 61). The film represents the director’s first experience of working abroad in a foreign film industry. This is also an experience that assumed a great deal of significance in Anderson’s career, but which has received little critical consideration overall.[6] Prior to The Singing Lesson, Anderson had begun to work with film professionals outside the British national industry, as instanced by his collaboration with the cinematographer Miroslav Ondříček on The White Bus (1966), a medium-length feature film, based on a short story by Shelagh Delaney. Anderson met Ondříček in Czechoslovakia in April 1965 during the filming of Milos Forman’s Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky, 1965). Although Ondříček spoke no English, the two men took an immediate liking to each other. Anderson promised the young cameraman that he would bring him over to Britain to collaborate on his next project. The Lindsay Anderson Archive at Stirling University contains an interview that Ondříček gave the Czech Theatre and Film News magazine (LA 5/1/3/12). The interview provides an example of the dynamic that informs Anderson’s vision of the filmmaking process: he sees it as a permanent struggle over who can rightly claim the ownership of the finished film: the artist who works within the parameters set by a given national film industry or the film director, irrespective of the national film industry in which she or he works. Ondříček comments:

Work is strictly controlled there. At the beginning I had no idea that every shot is recorded with all technical parameters. In case a shot comes out badly then it is clear whose fault it is. (LA 5/1/3/12)

The White Bus (1966): Lindsay Anderson and Miroslav Ondříček on set. Source: Lindsay Anderson Archive, University of Stirling.

It is tempting to read Ondříček’s assessment of the working conditions within the British film industry against the backdrop of the economic and political situation in his own country. The idea of accountability could easily be read either as an indictment of a capitalist society where “time is money” (LA 5/1/3/12), or an indirectcommentary on the state-controlled film industry operating in Czechoslovakia.[7] The underlying tension finds an echo in an article that Anderson wrote for The Times in May 1965, shortly after his first meeting with Ondříček. Speaking of the Czechoslovakian New Wave, Anderson highlights the apparent paradox of finding so much artistic creativity in such a highly regulated national film industry (Anderson, The Times 8). The British director contrasts the vitality of Czechoslovak film production to the situation in Britain where his film This Sporting Life (1963) had brought to a close a short-lived home-grown new wave. In a hardly disguised indictment of British production at that time, Anderson proclaims his yearning for a genuine artistic output, freed from both commercial imperatives and rigid critical trends, which, in his opinion, official platforms for the arts such as the National Film Theatre were setting (Anderson, The Times 8).[8]

Ondříček’s recollection of shooting The White Bus is also full of references to features of British everyday life with which he was unfamiliar. Cultural alienation found its most obvious expression in the language barrier between Ondříček, Anderson and the rest of the crew. The fact that Ondříček spoke hardly any English was, however, of no concern to Anderson (Anderson, “White Bus” 106). A similar situation would arise during the shooting of The Singing Lesson where Anderson chose a cameraman with little command of the English language (Anderson, “The Singing Lesson” 102). Their cultural differences manifested themselves through a language barrier, which instead of impeding Anderson’s artistic process, became one of its constitutive elements. The conditions that presided over the making of The Singing Lesson bring out the nature of the tension that Anderson sees is at the heart of his filmmaking practice.

A British Director in Poland

Anderson was in Warsaw in 1966 to direct a production in Polish of John Osborne’s play Inadmissible Evidence (1964). During this time, he met the director of the Documentary Studio who invited him to make a film about “anything [he’d] like” (Anderson, “The Singing Lesson” 102). Joanna Nawroka, his assistant at the Contemporary Theatre, advised him to go and watch the classes run by a well-established musical theatre performer, Professor Ludwik Sempoliński (102). Anderson decided to use the professor’s fourth-year students as the focus of his new project and returned to Warsaw in April 1967 to film what was to become The Singing Lesson.

Anderson’s central idea behind the project was to create a “sketchbook, or a poem” that would offer a dual vision of life in 1960s Poland (1/05/5/1). He set out to contrast the innocence and youthful spirit of the students to the harsher reality of the outside world of which the students would soon be a part:

Into this sequence of songs will be cut images from “real life”—evoking the past and life today: a street memorial … flowers dedicated to a fallen soldier of yesterday—relics of wartime agony—faces in the crowded streets of today … shoppers buying food, workers crowding on to transport on their way home. The purpose of these shots is not to show an exotic, picturesque or ‘tourist’ view of Warsaw. But rather to contrast the fantasy of the songs with the reality of everyday existence—the unromantic facts of life with the freshness of youth that has still to come to terms with it. (LA 1/05/2)

The idea of contrast between two worlds, two realities, found itself replicated in Anderson’s own experience of the filming. A pattern involving a sense of both frustration and artistic fulfilment soon established itself. Whereas the students of the Warsaw Dramatic Academy appear to have provided Anderson with the motivation he needed to complete the project, he saw the film crew, on the other hand, as the source of a continuous creative struggle:

The selection of students was by chance, but I was struck by their enthusiasm, their ability and the freshness of their work. Even their mistakes had charm … (LA 1/05/2)

Shootings: Pierre sings “The Coat”, which I find very poetic and suggestive the more I hear it, and the enchanting Andrzej Nardelli sings “Groszki” [“Sweet Peas”] … unit discipline and communication become impossible, climaxing in the disappearance of the entire unit after the first song—which has involved endless delays and unnecessary retakes. I blow my top, and hate doing so, since it has to be at Sigmund … (Anderson, “Diaries” 175) [9]

In his two accounts of the making of the film, recorded over 20 years apart, he comes close to contradicting himself. Anderson praises the creative latitude he enjoyed while stressing the technical as well as the political restrictions that were affecting the Polish film industry at the time (Anderson, “The Singing Lesson” 103-4; Sussex 62).[10] An incident that occurred on the occasion of the screening of The Singing Lesson at the Documentary Studio demonstrates the nature of the relationship that Anderson established with the local film industry. Anderson relates the incident in a book review that he wrote for The Guardian in 1984. He describes how the Polish film director, Jerzy Bossak, then in charge of production at the Documentary Studio, expressed his dismay at the view of the “harassed faces from the Warsaw streets” (Anderson, “Commitment” 587). Bossak’s concern stemmed from Anderson’s choice to alternate shots of stern faces on the streets of the capital with those of Professor Sempoliński's carefree students. What had been a purely creative decision on Anderson’s part soon translated into a potentially dangerous situation for the Studio’s executives who had invited the British filmmaker to work for them:

“Why is nobody smiling?” asked Jerzy Bossak … There was no point, I realised, in my saying that I had just felt like that … Around me I heard voices whispering that this sequence was surely designed to evoke the finale of Wyspiansky’s The Wedding, “The symbol” (this is Michalek quoting Professor Kazimierz Wyka), “of a society drugged by inertia and incapable of action …” Vainly I protested that I had neither seen nor read The Wedding. Even if the evocation was unintentional, it would certainly be remarked and condemned by the censorship. Everyone would get into trouble. (587)

The Singing Lesson (1967): the final sequence. Source: Lindsay Anderson Archive, University of Stirling.

His 1984 article emphasises the political implication of the incident. Anderson describes the circumstances under which he worked in 1960s Poland in order to shed light on the nature of the oppressive context that was then presiding over all artistic creation in the country. He mentions that his film was subjected to censorship while downplaying the impact it had upon him:

I got away with my sequence, just. When the censor arrived at the studio the next day, it was in the person of a nice, elderly lady. She thought my singing lesson was “charming”. (587)

Interviews with Sussex and Ryan in 1970 and the early 1990s, respectively, also acknowledge the relevance of the political context but relate it more explicitly to Anderson’s own creative process. In his interviews with Sussex, for instance, Anderson compares the “frustrations” that the respective film industries represented for him (Sussex 62). Furthermore, while stressing the impact that the “political pressures” had on the Polish film production (62), he also criticises the over-regulated nature of the British film industry, thereby implying that his work in Poland gave him more creative latitude (62). Anderson reiterates the point in his interviews with Ryan, comparing the enthusiasm and professionalism of his Polish cast to their British counterparts whom the British director regarded as incapable of that same “spontaneous” spirit (Anderson, “The Singing Lesson” 103). This is not to say, however, that Anderson placed his own artistic demands over the harsh reality that characterised the working conditions of his fellow film directors in Poland at the time. Rather, he found in the genuine social and political alienation that pervaded the life of Polish citizens a way of externalising his own feelings towards the British film industry.

National Cinema and the Transnational Artist

A letter written by the Czech film director Jaromil Jireš to Anderson in January 1965 illustrates the nature of the creative alienation that the British director experienced in his own country. In that letter, Jireš encourages Anderson to disregard the opinion of the critics who had given negative reviews of the British director’s production of Julius Caesar (1964) for the London Royal Court. Jireš then establishes an implicit parallel between the fickleness and lack of vision of the critics with the actor Richard Harris’s decision to leave the play two weeks into rehearsals. He contrasts Anderson’s artistic ideals, which he sees as impervious to any notion of compromise, to the fallibility of the film industry that Harris and the critics embody. Anderson’s quest for the absolute in a relative world—“Tu veux faire les choses absolus, les choses absolus dans ce monde absolument rélatif!” [You are striving for the absolute in an absolutely relative world] (LA 5/01/3/12) (author’s own translation)—become the expression of the director’s work ethic. In other words, just as the shots of the students at the Warsaw Dramatic Academy placed youth, innocence and a creative spirit in opposition to the drab reality of 1960s Poland (Anderson, “The Singing Lesson” 104), Anderson’s artistic ideals found themselves besieged in a national film industry that undervalued the role of the artist.

Allison Graham notes the centrality of the debate surrounding the definition of national identity in Anderson’s work. She establishes a direct correlation between the director’s claim that “the failure of British cinema [is] the failure of national self-belief” (20), and the impact that “political and cultural limitations” have (21), in his opinion, upon the artistic potential of film in society. Graham includes Anderson’s contribution to the Free Cinema experiment in the director’s exploration of British cinema’s national identity. She quotes from an article by Gavin Lambert written on the occasion of the screening of the first Free Cinema Programme at the National Film Theatre in London in February 1956. Lambert highlights the films’ concern with the “[i]solation of the individual, isolation of the crowd, isolation of escape” (qtd. in Sussex 28). Graham, echoing Lambert’s review, argues that the Free Cinema films present the image of a broken British society. More specifically, she evokes the “depth of social division in England” (28) that these films convey.

Similarly, Anderson experienced a sustained sense of alienation while working as part of the British film industry. To him, there appears to be a gap between the style and content of his films and the cultural model they should be a part of:

I would say all my films have been sore thumbs as far as the British film industry is concerned. I don’t know how to make a British film which the British want to see. I’ve never felt part of the film industry here, and I don’t think I am. Read the film books—I’m rarely there … I don’t exist anymore as a British film-maker. I have never had a nomination, not that I give a damn, from the British Film Academy. That is perfectly ok because I know what I do is not to the English taste—Fuck’ em. (Anderson qtd. in Hacker and Price 55)

In other words, the lack of interest that he perceived in his films stems from their absence of commonality with the prevailing cultural model of filmmaking: If…. became a symbol of the director’s estrangement from his own country’s cultural identity, which proves ironical as the film is set in an English public school. To quote Anderson:

I don’t think If…. was influential at all. Another Country is to me much more like a British film, it’s glossy, and photographed in that seductive way. There’s all the difference in the world between If…. and Another Country. If…. is a sort of sore thumb. (55)

Anderson’s overview of the British filmmakers’ community subsumes the question of national identity under an allegiance to a model of directorial practice. In his view, being a British film director translates into a strong command of the technical side of filmmaking to the detriment of the artistic dimension. David Lean’s work epitomises the British directorial style that Anderson disdains and sees as devoid of any genuine commitment to art. In an interview with Hacker and Price, Anderson appears to establish a correlation between Lean’s Englishness as a film director (“David Lean is a very ‘English’ film-maker”) and the latter’s strong mastery of technique and form (55). This is a point that he makes throughout the interview in different ways, thereby implying an inherently British—or English—focus on the technical aspect of film directing in the country (54-5).

It follows that Anderson defined himself as the antithesis to Lean’s directorial style, which functions as a tacit proclamation of his un-Britishness. In the interview with Hacker and Price, the practice of locating the director’s artistic prerogative in the abstract rather than the technical finds a definition: it becomes an issue of control over the medium and the process itself:

I want total control working with extremely good, skilled, and sympathetic collaborators, which is of course difficult; and of course, “control” means “responsibility”. (Anderson qtd. in Hacker and Price 46)

In other words, Anderson, in spite of an apparent lack of interest in the technical aspects of filmmaking, does not advocate an amateur approach to his craft.[11] The notion of control that he introduces here functions as an acknowledgement of the un-Britishness of his directorial practice.This sheds an interesting light on Ondříček’s remark about the degree of control that operates in the British film industry. The extent to which the various professionals involved in the making of a film are held responsible for the technical control of their respective areas should not, in Anderson’s opinion, be confused with the creative control that comes from the film director. Although Anderson sees the active input of each collaborator as essential, he also believes that this does not absolve the film director of his artistic responsibility for the work. As early as 1948, he stated that the filmmaking process was a fusion of creative elements with “a central figure, one man conscious of the relative significance of every shot …” (Anderson, “Creative Elements” 199). His definition of the term control further recalls the artistic and critical integrity that he saw as an essential part of the filmmaking process in “Angles of Approach” (Anderson 189-93).

Britannia Hospital and the National Identity of Anderson’s Cinema

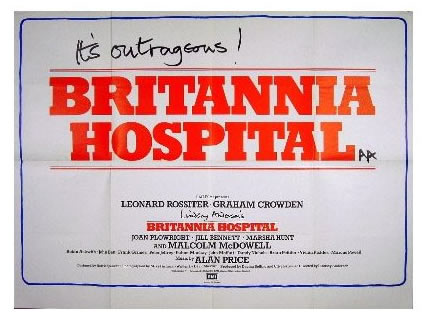

Britannia Hospital (1982): film poster with Anderson’s personal annotation. Source: Lindsay Anderson Archive, University of Stirling.

Britannia Hospital (1982) tells the story of a British hospital gradually falling into a state of absolute chaos: the ancillary staff is on strike; they call for the end of all privileges granted to the hospital’s private patients. Outside demonstrators blocking the access to the emergency ward also denounce the two-tier health care system as well as the morally reprehensible presence of an exile African dictator. The whole situation threatens the visit of a member of the royal family invited to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the founding of the hospital. The film culminates with the angry mob storming onto the grounds and into the brand new building adjacent to the hospital where Dr. Millar supervises the secretive project ‘Genesis’. At that point, Dr. Millar invites the demonstrators to join the lecture he was about to give to a panel of special guests on his plan to create a better mankind. The film concludes with a shot of the Genesis machine that proclaims in a synthetic voice the redundancy of the human race.

The Anderson Archive contains a collage that Anderson made around the time of the production of Britannia Hospital (LA 1/09/6/3/1). This collection of newspaper cuttings, mostly from the British press, features articles that all dwell on social or cultural anomalies. There is a particular emphasis on the British health care system that is presented as being in a state of total disarray. The connection with Britannia Hospital’s storyline comes to light in the form of an article reporting the case of a dead patient left in the hospital breakfast room overnight due to a staff shortage. Anderson’s collage also echoes an earlier one made on the set of If….. They both form part of his directorial practice and, as such, comment on the context surrounding the making of his films. In the case of If…., Anderson stresses that the photos and slogans were selected so that they could not be connected to any specific date or event. The element of atemporality helps shift the definition of Britishness to a consideration of the community itself—understood as a delineated space where individuals share common cultural markers—here manifested through the regulations that govern the everyday life of a London hospital.

Anderson and critics alike presented Britannia Hospital as a metaphor for the state of the United Kingdom in the early 1980s (LA 1/09/6/11; LA 1/09/6/7/17). The film achieves this through a storyline that simultaneously proclaims and undermines the relationship between the particular and the universal that underlies Anderson’s work as a whole. Graham comments:

Anderson’s films remain the brightest examples of the potential of British cinema. They deal honestly and intimately with their social environment, yet transcend it to capture, in E.M. Forster’s words, “that peculiar pushful quality” of universal works of art: “the excitement that attended their creation hangs about them, and makes minor artists out of those who have felt their power”. (152)

The action of the film is restricted to the hospital building and the adjoining research centre. Louis Marcorelles, in a review of the film written for Le Monde,[12] highlights the analogy that Anderson made between the location of his film and the social and historical context of the country (Marcorelles, “Britannia Hospital”). The hospital becomes the space where the glory of the past is celebrated and takes precedence over the reality of the present. Conversely, the research centre where Professor Millar operates represents a future without any historical or social dimension: a disembodied voice coming out of a giant, brain-like machine fails, for instance, to complete a monologue taken from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, celebrating Man’s greatness (“Britannia Hospital”). The apparent contrast between the two places serves only to reinforce their sameness: the workers occupying the hospital building and the members of the Royal family visiting it follow the rituals that correspond to an outdated conception of their country. Professor Millar and his team of scientists, on the other hand, do not relate to any pre-determined social order. The advancement of science defines their sense of identity and purpose.

In January 1981, Anderson wrote a letter to Erwin Axer, a friend and Polish theatre director, in which he conveys his frustration with the British film industry and the state of his film career (LA 5/01/3/14). The letter alternates between his fear that he might not be able to raise the financing for Britannia Hospital and a growing desire to accept a film offer from the United States. Anderson’s unhappiness is the result of a very personal dilemma: on the one hand, he saw the situation in which the British cinema found itself as the main factor underlying the lack of financial backing for the film; on the other, the acceptance of any offer originating from the United States was then perceived more as a betrayal of his artistic principles than a true professional opportunity. He comments to Axer:

I have been offered a film in America, quite an interesting subject, and of course very well paid. I would prefer to make a film in Britain, which I can make more out of my personal experience and conviction [sic]. But the British do not seem too anxious to support me in this idea. (LA 5/01/3/14)

Anderson’s resentment towards the British film industry was not new: letters written to Gene Moskowitz in the 70s and early 80s expressed a similar dismay at the lack of opportunities made available to filmmakers who, like himself, still had not left for America (LA 5/01/2/37/9; LA 5/01/2/37/31). However, in the case of Britannia Hospital, a sense of urgency emerged: in the January 1981 letter to Erwin Axer, Anderson likens the fate of the British film industry to the anticipated conclusion to his own film directing career. The cause for their respective doom, however, lies in opposite directions. An entry in Anderson’s diaries, dated 30 December 1980, contrasts the narrow-mindedness of one with the revolutionary and, therefore, suicidal spirit of the other:

From one angle Britannia Hospital is the logical, courageous development of my own style, my own thoughts and feelings. From another it is a stubborn repetition of ideas which have already proved unpopular, unwelcome, unacceptable to all except an increasingly shrinking minority. (Anderson, “Diaries” 389)

Anderson’s last British film is unique in the extent to which it betrays the director’s awareness that Britannia Hospital implicitly projects onscreen what it meant for Anderson to work within the framework of the British film industry at the time. The connection between the storyline—the state of a country in the final throes of a terminal illness—and the state of the British film industry was noted in the French press following the film’s presentation at Cannes in 1982.

The film critic Serge Daney, for instance, regards the surgery scene involving Professor Millar as a modern-day Dr. Frankenstein, as a projection of what Anderson thought of the film industry in his country (Daney “Coule, Britannia!”). Daney opens his article by stating that the British director rolls two metaphors into one: the first equating the state of the country with a hospital in a state of total disarray and the second implying that the situation extends to the ill-health of the British cinema. Furthermore, Daney sees Professor Millar as the onscreen equivalent of the director. For him, Anderson exhibits all the signs of the mad scientist/doctor who persists in operating on a patient long past any hope of recovery, symbolising both the state of the British cinema—here labelled as “le cinéma anglais” (“Coule, Britannia!”)—and the director’s growing loss of interest in defending its cause. In other words, the frenzy with which Professor Millar sews back together human body parts belonging to two different bodies is meaningless: the storyline in the film confirms this as the whole surgery fails, culminating in the death of Millar’s assistant and the, by-then, headless patient biting the hand of his creator. Daney associates the imagery pervading the scene with Stanley Kubrick’s metaphysical signature in 2001: Space Odyssey—“un exit métaphysique à la Kubrick” [A Kubrickian metaphysical exit] (“Coule, Britannia!”) (author's own translation)—but argues that Anderson fails to convince. He suggests instead that the British director look into the causes underlying the ill-health of British cinema, as opposed to reluctantly attempting to save it (“Coule, Britannia!”). It is worth noting that the reviewer judges the pertinence of Anderson’s project in the light of the director’s own interrogation about his national background. Daney highlights the fact that fighting for the cause of British cinema had become a lonely affair—most of Anderson’s contemporaries having left to work in the United States (“Coule, Britannia!”).

In “The Concept of National Cinema”, Andrew Higson situates the concept of a national identity for films at the intersection between production and consumption (Higson 132). His intention is to focus on the conditions under which a given audience—defined according to economic, social and cultural factors—experiences a specific national cinema. Higson offers a definition of national cinema that includes economic factors: national cinema understood as domestic film production (132), aesthetic considerations—“what are these films about? Do they share a common style or worldview?” (132)—and, finally, the significance of “consumption” patterns (133). In other words, a national cinema is situated at a crossroads between economic, social and cultural influences. Here, Higson’s definition provides a frame for the feeling of rift that informed Anderson’s approach to the question of national identity in his films. To quote Anderson discussing the “rush to conformism” that underpinned filmmaking in his country (qtd. in Friedman and Stewart 165):

[T]he possibilities of filmmaking in Britain for someone of my temperament are very difficult, very limited … The violent rejection of my last British film, Britannia Hospital, is evidence of this … We’re accustomed … to a film culture in which absurdly grotesque horror is a part of a tradition. My film was so satirical that it demanded a sense of humor. Of course, the trouble is that people have begun to think in clichés. If they think they’re going to see a satirical social film, then they’re not prepared for the kind of extended satire present in Britannia Hospital. (170)

Britannia Hospital highlights the extent to which Anderson conceived of his filmmaking career as a source of perpetual conflict. In a letter to Louis Marcorelles written shortly before the film was shown at the 1982 Cannes Festival, he likens his situation to the struggles that dissidents encountered on a daily basis behind the Iron Curtain (LA 5/01/2/33/24).[13] He regards conformism as a cultural tool of oppression and the media as the state police in charge of its enforcement (LA 5/01/2/33/24). Dissidence for Anderson became a guarantee of artistic value and, by implication, a marker of his marginalisation from the British national industry. Anderson’s reference to George Orwell’s 1984 suggests the connection between the two:

1984 has come—or is coming—but in very different clothes from the drabl [sic] grey designed for it by George Orwell. On the contrary, it is lavishly costumed and subsidised. And media-celebrated. (LA 5/01/2/33/24)

To conclude, Higson, in Waving The Flag, insists on the discursive aspect that underlies the construction of a national cinema. In an echo of Benedict Anderson’s view that the cultural is a historical anomaly, he argues that the “critical discourses” that describe a national cinema also by implication construct its identity (Higson 1). Higson further defines the Britishness that underlies the form and content of British films as “a publicly imagined sense of community and cultural space” (1). The representation of Britishness for Anderson stems from a permanent conflict: he acknowledged the cultural and social legacy that had framed his work but regarded it as essentially oppressive. The director’s predilection for selecting institutions as settings for the action of his films—school, hospital, organised sports, the military, the justice system—constitutes the external manifestation of the duality that informed his vision.

Notes

1. The Lindsay Anderson Archive is part of the University of Stirling’s Special Collections. The archive includes Anderson’s personal and professional correspondence, the diaries that he kept for over forty years, as well as the promotional and production material and photographs relating to all the films, TV projects, theatre plays and various other works in which the director was involved in the course of his career. The collection is divided into six sections each covering a major part of Anderson's life and work. When referring to the Lindsay Anderson Archive, I will follow the cataloguing system in use in the Special Collections. A reference to Anderson’s archived correspondence will read for instance, LA 5/01/. For further information, please refer to the Lindsay Anderson Archive page, listed in the Work Cited section.

2. See Anderson, “Value of an Oscar” 54-55.

3. “LES MISTONS sont passes tres bien. Tres chaleureusement recu, et je crois que le mouvement CAHIERS-CINEASTES est bien lance en Angleterre … C’est vraiment formidable, tout ce que vous faites, toi et les autres, en France maintenant. Et tres important. Dans ce pays de cinema mort tout cela semble miraculeux”. The quote in French is verbatim: lack of accents and grammatical/spelling inaccuracies appear in the original.

4. The full title of the article is “Realism in British Films: The Personal Approach”, which evokes Anderson’s life-long admiration for Humphrey Jennings and his ability to create a highly individual work within the constraints of the Griersonian school of documentary filmmaking. See also Anderson, “Only Connect” 358-65, for a fuller account of Jennings’s work and the extent to which Anderson was influenced by his style of filmmaking. See also Hedling ch.2;3; Sussex 23-8, for the influence of Jennings and Vigo on Anderson’s documentaries.

5. In the course of his career, Anderson directed six features films for the cinema: This Sporting Life (1963), The White Bus (1966), If…. (1968), O Lucky Man! (1973), Britannia Hospital (1982), The Whales of August (1987). He also directed a number of productions for British television from the 1950s up until the early 1990s. Anderson directed the mini-series Glory! Glory! for HBO in 1989, which, with The Whales of August, is the only other project that he undertook in the United States.

6. In a letter written to his friend Louis Marcorelles in April 1987, Anderson betrays his fondness for the short film: he regards The Singing Lesson as one of his best works and as representative of his career-long striving for a “poetic-lyric” style:

[T]he little film I made in Warsaw … I only mention it because I think it’s one of the best things I’ve done … Not of course a “documentary” [sic] in the classic English style, more poetic-lyric than social … I think I shall ask for it to be shown at my funeral service. (Anderson LA 5/1/2/33/59)

Sussex (61-7) presents a substantial account of the conditions that led to the production of the short film. She also provides a detailed analysis of the songs performed by the students and the themes and filming style adopted by Anderson. By contrast, Erik Hedling’s otherwise extremely thorough overview of Anderson’s work in the cinema provides very little commentary on the Polish project.

7. See Hames 1-3, for a fuller account of the economic and political conditions under which films were produced in Czechoslovakia, prior to the fall of the Dubček regime in 1968.

8. See Murphy for an account of the nature of the British film industry in the 1960s, especially with regard to the amount of control that companies such as Rank and ABC still held over production and exhibition of British films.

9. This is how the entry reads in Anderson’s Published Diaries.

10. See article by Moskowitz, Sight and Sound, Winter 1957/58 for a detailed account of the working conditions under the state-controlled film industry in Poland after World War II. See also Coates, The Red and The White: The Cinema of People’s Poland.

11. See also Anderson (1970: 101): “ I myself have always been strongly biased in the direction of form and discipline … these principles apply whatever your means … that is what is missing in the work of a lot of young people today. Direct cinema, or cinéma vérité, has resulted in a lack of artistic form and discipline. It’s become very loose and self-indulgent often”.

12. Louis Marcorelles was a prolific French film critic. He was a contributor—amongst many other publications—to Cahiers du Cinéma and the most influential editor of Le Monde’s Cinema column until the late 1980s. The first record the archive holds of Anderson and Marcorelles’s correspondence dates back to 9 November 1956 – LA 5/01/2/33/1. They exchanged letters regularly until Marcorelles’s death in 1991.

13. Anderson (28 April 1982: LA 5/01/2/33/24): “I feel it is more and more important that individual, dissident talents should survive and be supported in the cinema. Because we do have our dissidents here in the West—though not perhaps as many of them as they have in the East …”

References

1. Anderson, Lindsay. “Angles of Approach”. Sequence 2, Winter, 1947, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 189 93. Print.

2. ---. “A Child of Empire”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 35-40. Print.

3. ---. “Commitment in a Cold Climate”, Review of Politics, Art and Commitment in the

East European Cinema. David Paul ed., in The Guardian, 7 May 1984, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 583-9. Print.4. ---. “Creative Elements”, Sequence 5, Autumn 1948, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 194-9. Print.

5. ---. “Discussion with Lindsay Anderson”, in J. Hacker and D. Price, 1991. 44-56. Print.

6. ---. “Every Day Except Christmas Except Christmas”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 70-2. Print.

7. ---. “Finding a Style”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 59-60. Print.

8. ---. “Free Cinema”, Universities and Left Review, Summer, 1957. Reprinted in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 73-7. Print.

9. ---. “Lindsay Anderson”, in J. Gelmis ed., 1970. 95-110. Print.

10. ---. Letter to François Truffaut, BFI, 9 September, 1958—scanned and forwarded to author. Email.

11. ---. “My Country Right or Wrong?”, Sunday Telegraph Magazine, 26 June, 1988. Reprinted in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 33-4. Print.

12. ---. “Nothing Illusory about the Young Prague Film-Makers”, The Times, 19 May 1965. 8. Print.

13. ---. “Only Connect: Some Aspects of the Work of Humphrey Jennings”, Sight and Sound, April June 1953, reprinted in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 358-65. Print.

14. ---. “Sequence”, Introduction to a Reprint, 30 March 1991, reprinted in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 41-9. Print.

15. ---. “The Singing Lesson”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 102-4. Print.

16. ---. “Starting in Films”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 50-5. Print.

17. ---. “The Value of an Oscar”, Broadcast on the BBC Home Service, 9 September 1956, reproduced in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 56-8. Print.

18. ---. “The White Bus”, commentary, 1994, in P. Ryan ed., 2004. 105-7. Print.

19. Another Country. Dir. Marek Kanievska. Orion Classics, Twentieth Century Fox film Company, 1984. Film.

20. À Propos de Nice. Dir. Jean Vigo. 1930. Criterion Collection, Artificial Eye, DVD release 2004. Film.

21. Britannia Hospital. Dir. Lindsay Anderson. EMI Films, United Artists Classics (1983 USA), Studio Canal (worldwide 2006). 1982. Film.

22. Britannia Hospital. LA 1/09/. The Lindsay Anderson Archive. Special Collections. University of Stirling. Print.

23. Coates, Paul. The Red and the White: The Cinema of People’s Poland. London: Wallflower Press. 2004. Print.

24. Correspondence. LA 5/01/. The Lindsay Anderson Archive. Special Collections. University of Stirling. Print.

25. Daney, Serge. “Coule, Britannia!”, Libération, 8 novembre, 1982, reprinted in Revue de Presse Numérisée Britannia Hospital (1982), BiFi, Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française, Paris, on-site digital library. Print.

26. Dixon, Wheeler W. ed. Re-viewing British Cinema, 1900-1992: Essays and Interviews, Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1994. Print.

27. Dwaj ludzie z szafa [Two Men and a Wardrobe]. Dir. Roman Polanski. Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, The Criterion Collection (USA, 2003, DVD release), 1958. Film.

28. “End of a Movement? What Free Cinema Has Achieved”, The Times, 18 March 1959: 13. Print.

29. Friedman, Lester, Stewart, Scott. “The Tradition of Independence: An Interview with Lindsay Anderson”, 1989, in Wheeler W. Dixon ed.,1994, 165-76. Print.

30. Gelmis, Joseph. The Film Director as Superstar, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Comp, Inc, 1970. Print.

31. Glory! Glory! Dir. Lindsay Anderson. HBO, 19 February 1989. Television.

32. Graham, Allison. Lindsay Anderson, Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1981. Print.

33. Hacker, Jonathan, Price, David. Take Ten: Contemporary British Film Directors, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991. Print.

34. Hames, Peter. The Czechoslovak New Wave, London: Wallflower Press. 2005. Print.

35. Hedling, Erik. Lindsay Anderson: Maverick Film-Maker. London/Washington: Cassell. 1998. Print.

36.Higson, Andrew. “The Concept of National Cinema”, Screen 30:4, 1989, 36-46, reprinted in C. Fowler ed. The European Cinema Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 2002, 132-42. Print.

37. Higson, Andrew. Waving the Flag: Constructing a National Cinema in Britain, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1995. Print.

38. If…. Dir. Lindsay Anderson. Memorial Enterprises, Paramount Pictures.1968. Film.

39. Lambert, Gavin. “Free Cinema”, in Sight and Sound, Spring, 1956, 173-7. Print.

40. Le Beau Serge. Dir. Claude Chabrol. Les Films Marceau (France), United Motion Pictures Organization (UMPO) (USA). 1958. Film.

41. Les Mistons [Brats]. Dir. François Truffaut. Gala Film Distributors, Les Films de la Pléiade, 1957. Film.

42. http://www.is.stir.ac.uk/libraries/collections/anderson/Thecollection.php. Web.

43. Loves of a Blonde [Lásky jedné plavovlásky]. Dir. Milos Forman. Filmové Studio Barrandov, Prominent Films.1965. Film.

44. Marcorelles, Louis. “Britannia Hospital, de Lindsay Anderson: Ouragan sur l’ Etablissement”, Le Monde, 4 novembre 1982, reprinted in Revue de Presse Numérisée Britannia Hospital (1982), BiFi, Bibliothèque du Film, Cinémathèque Française, Paris, on-site digital library. Print.

45. McCarthy, Matt. “Free Cinema—In Chains”, Films and Filming, February, 1959, 10-7. Print.

46. Moskowitz, Gene. “The Uneasy East: Aleksander Ford and the Polish Cinema”, Sight and Sound, 27:3, Winter 1957/58, 136-40. Print.

47. Murphy, Robert. Sixties British Cinema. London: BFI. 1997. Print.

48. O Dreamland. Wr/Dir. Lindsay Anderson. A Sequence Film, 1953. Film.

49. O Lucky Man!. Dir. Lindsay Anderson. Memorial Enterprises, Warner Bros. Pictures, Warner Columbia Film. 1973. Film.

50. “Progress of Free Cinema”, The Times, 3 January 1958: 3. Print.

51. Raz, Dwa, Tresz/The Singing Lesson. Dir. Lindsay Anderson, Piotr Szulkin. Contemporary Films (Warsaw Documentary Studio), 1967. Film.

52. “Realism in British Films: The Personal Approach”, The Times, 2 February 1956: 10. Print.

53. Ryan, Paul ed. Never Apologise: The Collected Writings, Lindsay Anderson. London: Plexus, 2004. Print.

54. Spare Time. Dir. Humphrey Jennings. GPO (General Post Office) Film Unit. 1939. Film.

55. Sussex, Elizaeth. Lindsay Anderson, New York: Praeger. 1970. Print.

56. Sutton, Paul ed.. The Diaries: Lindsay Anderson. London: Methuen, 2004. Print.

57. The Bridge on the River Kwai. Dir. David Lean. Columbia Pictures, Warner Bros, 1957. Film.

58. The Lindsay Anderson Archive. Special Collections. University of Stirling.

59. The Singing Lesson. LA 1/05/. The Lindsay Anderson Archive. Special Collections. University of Stirling. Print.

60. The Whales of August. Dir. Lindsay Anderson, Nelson Entertainment, Finnkino, Alive Films. 1987. Film.

61. The White Bus. Dir. Lindsay Anderson. United Artists Corporation, EMC. 1967. Film.

62. This Sporting Life. Dir. Lindsay Anderson. J. Arthur Rank Film Distributors, Continental Distributing. 1963. Film.

63. Thursday’s Children. Dir: Guy Brenton, Lindsay Anderson. World Wide Pictures, A Morse Productions, 1954. Film.

Suggested Citation

Gourdin-Sangouard, I. (2011) 'Lindsay Anderson: Britishness and national cinemas', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 1, pp. 36–57. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.1.04.

Isabelle Gourdin-Sangouard, M.Phil, is in the final stages of her doctoral thesis at Stirling University. Her research is part of the AHRC-funded project ‘The Cinema Authorship of Lindsay Anderson’ (2007-2010) that will culminate in the publication of: Lindsay Anderson: Cinema Authorship, John Izod, Karl Magee, Kathryn Hannan, Isabelle Gourdin-Sangouard (Manchester University Press, forthcoming). She has also contributed a number of conference papers and articles to the project. She is a teaching assistant in the Deptartment of Media & Culture Studies at the University of Stirling. She taught film, media and French language and culture, as a lecturer at Aberdeen Business School, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen (2004/7) and as a teaching assistant at the University of Aberdeen (2000/6). Her research interests also include the area of media and education, with presentations and a workshop at IAMCR 2006 and ECREA (2007 European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer School).