Back to the Future: The European Film Studies Agenda Today

Laura Rascaroli

As a critical category, “European cinema” is anything but a recent invention; film history books, indeed, have always included central and substantial sections devoted to it. Of course, this tradition in itself does not presuppose the existence of a continental cinema as a coherent whole or organised structure, or even of an aesthetics that could be described as European, but only that of an interpretative discourse based on the study of a set of historically and geographically contiguous national histories, whose intersections in truth have been rarely foregrounded and investigated (a noteworthy exception being the New Waves of the 1960s and 1970s, which have always been described as an interconnected, transnational phenomenon). At the same time, the emergence and continued existence of the critical category did establish European cinema as an object of study; and the idea of a style and approach to filmmaking that can be called European has been advocated by the way in which many non-European filmmakers—among whom New Hollywood directors such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola—referred and paid homage to European auteurs as a model and as a source of inspiration. European cinema has thus always existed within these and other critical, scholarly and artistic discourses, both as an aesthetic object and as a set of allusions. Such allusions were ultimately ideological, insomuch as they set the parameters of European film in comparison and contrast to Hollywood, on the basis of a set of charged binaries, such as industry vs. auteurism, escapism vs. realism, cinema of action vs. cinema of inaction.

The original edition of Georges Sadoul’s Histoire d'un art: le cinéma des origines à nos jours (Paris: Flammarion, 1949)

Film scholars are today engaged in a reappraisal of the category “European cinema” and are thus directly or indirectly questioning what it has meant and stood for in the course of a century. Since the 1990s, the crisis of the long-established paradigms of national film and of auteur theory, but also those of Second and Third Cinema, in the face of changed social, cultural and economic realities, produced, as we know, an urgent need for novel critical categories. The concept of transnational cinema,[1] in particular, has emerged during the last two decades as a response to two main phenomena: first, the appearance and rapidly growing fortune of the term “transnational” within theoretical and analytical fields of such subject areas as economics, to begin with, and then human geography, sociology, social anthropology and cultural theory; second, the desire to account for the emergence of intercultural cinematic imaginations, for instance those represented by Beur film, by British-Asian cinema, or by the many émigré/hyphenated/cosmopolitan/diasporic directors working throughout Europe.

While we grapple with definitions and at times struggle to describe these filmic realities, some of which seem resistant to all terminological efforts, the transnational label has gathered momentum. This is probably because it emerges within influential theories of globalisation and late-capitalism, to describe phenomena linked to flexible accumulation and time-space compression, which are associated with the effects of the weakening of the importance of nation states and of the increasing mobility of monetary capital on the global economy. When applied to the field of cultural production, then, the term is associated to ideas of “syncretism, creolisation, bricolage, cultural translation, and hybridity” (Vertovec, 451). Thus, transnational cinema becomes a germane expression that helps us to define and encapsulate a range of phenomena, both economic and cultural: the increased hybridism of the films produced in Europe today; the peculiarities of multinational co-production, of EU funding and of programmes such as EUROIMAGES; the internationalisation of markets and the effects of new technology and platforms for the distribution and consumption of films that are not geographically anchored (especially the Internet). While not entirely unambiguous, the concept appears to offer new metaphors for the definition of European cinemas and the exploration of its mutating contexts of production and of distribution, as well as of its artistic practices. Other terms and critical frameworks are also emerging that attempt to give account of the ways in which film is today increasingly migrating from the traditional cinema theatre to new environments and screens, a phenomenon accompanied by the change from the analog to the digital image, and from old forms of consumption to others that reflect novel technological and economic panoramas.

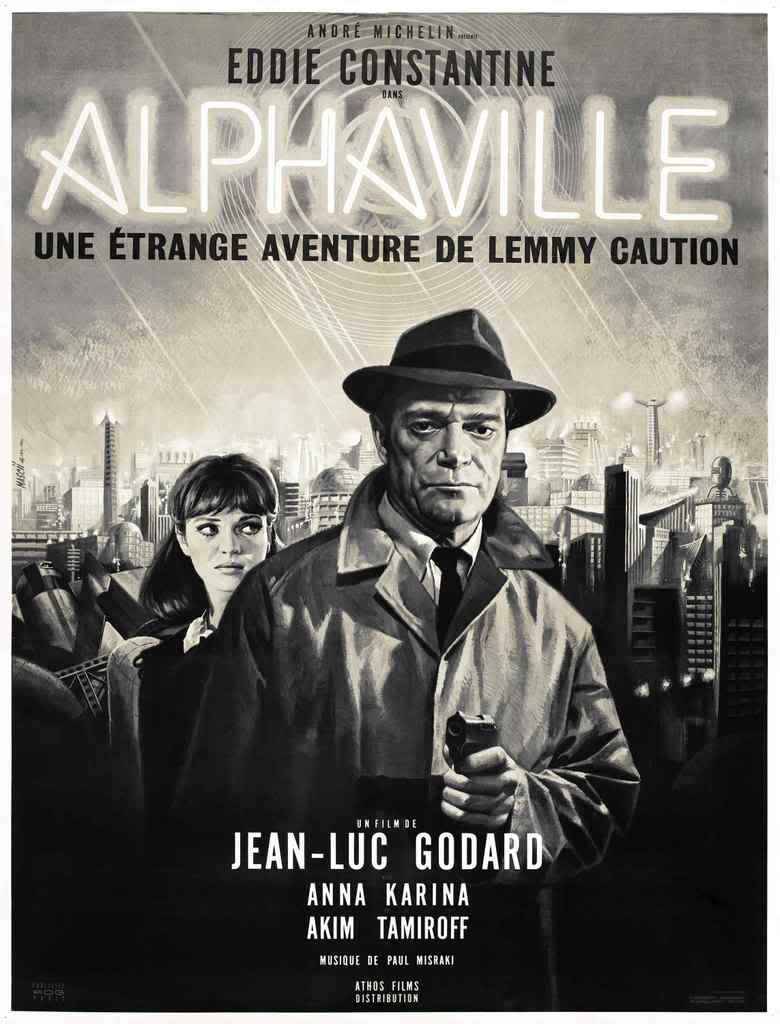

In 1965, Jean-Luc Godard—the quintessential European auteur, the first cinephile director, the man who took it upon himself to reinvent the cinema and then to declare its death—directed a black-and-white science-fiction film noir: Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution. Mixing genres, combining a distant future and the recent past, pop and high art, total alienness and twentieth century Paris, dystopian scenarios and modernist architecture, the celebration of familiar tropes and the annihilation of stereotypes, Godard made a highly hybrid and visionary film that was many things at once, but also irreducibly singular. With international funding, an expatriate American lead actor (famous in France and Germany for his roles as British pulp character Lemmy Caution), foregrounding Paris simultaneously as the heart of European modernism and as the standardised, international metropolis of the future, Alphaville nodded to the tropes of an Americanised global culture while being utterly European—and the product of the post-New Wave coproduction practices of continental art cinema. Alphaville was a film that both exploited and exploded the tropes, conventions and expectations that constituted “European cinema” as a commercial product, as a critical concept and as an aesthetic category.

A poster of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution (1965)

There is no better title, then, for a new journal that proposes to explore the constitutive hybridity of the moving image—analog and digital, commercial and avant-garde, mainstream and independent, popular and elitist—without forgetting how its roots spread in artistic and productive practices that have always been far more composite and multilayered than our critical categories seemed to wish to account for. Calling for the breaking down of disciplinary boundaries, media fields and critical categories, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media aspires to be a laboratory for new interpretative ideas on the moving image of yesterday, of today and of tomorrow. This inaugural issue, in particular, foregrounds cultural, spatial, productive and aesthetic issues that aim to set in motion our thinking about European cinema within multilayered critical, cultural and geopolitical models, and in light of the complexity of the flow of images that characterises our media landscape. The transnationality, transculturality and transmediality of contemporary European cinemas are undoubtedly going to shape and occupy the research agenda for some time to come.

Notes

1. As well as other, perhaps more specific terms such as “cinema of double occupancy”. See Thomas Elsaesser’s “Double Occupancy and Small Adjustments: Space, Place and Policy in the New European Cinema since the 1990s” in his European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005. 108-130.

References

1. Vertovec, Steven. “Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism”. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22.2 (1999): 447-462. Print.

Suggested Citation

Rascaroli, L. (2011) 'Back to the future: the European film studies agenda today', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 1, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.1.00.

Laura Rascaroli is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at University College Cork and the General Editor of Alphaville.