The Same Old Songs in Reagan-Era Teen Film

Michael D. Dwyer

Throughout the Reagan era, American culture was swept up in what sociologist Fred Davis called a “nostalgia wave”, with “the Fifties” as a crucial reference point for U.S. political, social, and cultural identity.[1] The styles, tropes, images and stars of the Fifties made their way to television (Happy Days, Nick at Nite), Broadway (Grease), even chain restaurants (Johnny Rockets) and video games (Rampage), while publications like Life and Esquire ran cover stories on Fifties nostalgia.[2] In his 1984 essay “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”, Frederic Jameson pointed out that “for Americans at least, the 1950s remained the privileged lost object of desire” (67). Media historians have identified “nostalgia for the 1950s, in the context of a vision of the future generated from that period” as one of the hallmark attributes of popular culture in the 1980s (Nadel 96–7) and argued that this tendency in the 1980s was “simply mirroring the fact that the decade itself, in its social history, was a sequel” (Palmer ix).

The implications of this were not limited to the entertainment industry. Nostalgia for the Fifties was a key cultural strategy in the rise of neoconservatism in the 1970s and 1980s, and no figure in American political life embodied such nostalgia more than President Ronald Reagan. David Marcus argues that Reagan’s ability to invoke the past offered the neoconservative political movement “an overarching sense of a national return to an earlier age after a period of American decline” and the opportunity to create “media accounts of the historical meanings of the 1950s” (37). The revision and reinterpretation of 1950s texts, styles, tropes and narratives in Reagan-era popular culture produced “the Fifties”, a cultural construct utilised for diverse rhetorical and political purposes. While recycling of past styles has long been a characteristic of American culture, the particular formulation of Fifties nostalgia constructed in the Reagan era served as the basis for enormous social and political changes to a degree that stylistic revivals of other eras simply have not. For contemporary Americans, Mary Caputi argues, the Fifties “bristle with an array of ideological connotations, a swirl of aesthetic resonances, a battery of moral implications so highly charged and emotionally laden that any mention of the decade in the current context far exceeds literal, historical references” (Caputi 1). One of the enduring legacies of the Reagan era, I argue, is the establishment of “the Fifties” as a particularly resonant cultural trope for contemporary U.S. society.

While images of the Fifties proliferated across American culture, Hollywood film studios and the American recording industry were among the era’s most enthusiastic purveyors of Fifties nostalgia. In an era defined by synergy, Fifties nostalgia was a feature of countless Hollywood soundtracks, even in films made for audiences too young to have personal memories of the era. While the range and complexity of Fifties nostalgia in Reagan-era popular culture deserves attention more widely, my focus is on one small iteration of this phenomenon. Specifically, I consider a string of Reagan-era teen films diegetically located in the 1980s which nonetheless invoke Fifties nostalgia through scenes wherein teenagers perform, through dance and lip-synch, oldies songs. What makes these scenes particularly interesting, in my view, is how the Fifties “speaks through” the body of the Reagan-era teenager. In Risky Business (Paul Brickman, 1983), Pretty in Pink (Howard Deutch, 1986), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (John Hughes, 1986), The Lost Boys (Joel Schumacher, 1987) and Adventures in Babysitting (Chris Columbus, 1987), the body of the Reagan-era teenager serves as the site at which a radical recontextualisation of rock music is accomplished. The 1980s, in this way, ventriloquises Fifties forms using the body of the white bourgeois teen to contain and reframe the discourses that surrounded rock and roll during its original production and reception.

However, we must not dismiss these soundtracks as simply ahistorical or regressive ideological objects. As Phil Powrie and Robynn Stilwell have argued, “analysing pre-existing film music is a kind of archaeology” wherein the historical, affective and ideological meanings of songs on Hollywood soundtracks must be unearthed to fully understand their textual operation (xix). As I will demonstrate, the function of 1950s songs on the soundtracks of 1980s teen films depends more on the historically contingent extratextual meanings of “the Fifties” in the Reagan era than any meaning intrinsic to the songs themselves. The political or cultural function of the nostalgia that Hollywood soundtracks might generate emerges from relations between the song, the film, their intertextual and extratextual networks, and the audiences who encounter them. Before considering the scenes of lip-synching in Reagan-era teen films, however, we must first understand how the emergence of new musical forms in the 1970s transformed the landscape of commercial American popular music. One of the most crucial redefinitions of the 1950s in the Reagan era was accomplished through the invention of a new pop music genre (and radio format): oldies.

Oldies: From Radio Dials to Hollywood Screens

To some degree, oldies have existed on the radio for as long as rock and roll has. The first “oldies DJ” in America took to the air in 1948, as Porky Chedwick of Pittsburgh’s WAMO spun his “dusty discs” of gospel, rhythm and blues, and what would eventually be known as rock and roll (Weigle). It was not until the early 1970s, however—with the success of Richard Nader’s revival tours, retro acts like Sha Na Na and soundtracks to films like American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973)—that oldies appeared in the form recognisable to us today. In 1972, The New York Times identified “golden oldies” as the hot new programming trend in radio, with stations like KOOL in Phoenix, WIND in Chicago, WCBS in New York and KUUU in Seattle increasing their market shares with the help of music from the Fifties. The Times speculates that oldies may be “a rejection of the heavy social messages in many modern lyrics” and a business practice designed to help an aging rock audience “forget its problems and return or at least recall those happy high school times—the prom, no wars, no riots, no protests, the convertibles at the drive-in” (Malcolm 21). In this view, oldies music was a way for aging baby boomers to assert and privilege the music of “their generation” over more contemporary music. At their root, such explanations of oldies’ popularity treat music as a marker of generational identity and belonging.

Scholarship on popular music has long identified the formation of group identity as one of rock’s primary functions. Much of this work is premised on the notion that consumption of rock music precipitates subcultural formations, wherein “rock rests on an ideology of the peer group as both the ideal and the reality of rock communion” (Frith 213). Writing explicitly about nostalgia produced via rock soundtracks, David Shumway argues that in the first Hollywood films to utilise wall-to-wall rock soundtracks “the most important effect of the music is not to provide commentary … but to foster generational solidarity” (38). This, as entertainment executives well know, makes rock music an especially potent tool for the purposes of directed and targeted marketing.

In the 1980s, the bond between Hollywood soundtracks and generational identity became extraordinarily lucrative. The valuable youth market gobbled up film soundtracks, music videos, videocassettes and other cross-platform film products. Scholars have primarily identified this marketing as dedicated to selling new music to the teenage demographic, but Reagan-era soundtracks often featured music that directly appealed to the listeners of oldies radio. Representative of this trend are films like The Buddy Holly Story (Steve Rash, 1980), Diner (Barry Levinson, 1982), Stand By Me (Rob Reiner, 1986) and La Bamba (Luis Valdez, 1987), among others. It is not only in films explicitly associated with nostalgia that oldies make an appearance. Rock music pre-dating the British Invasion was featured on soundtracks of science-fiction fare like Weird Science (John Hughes, 1985), mainstream comedies like Stripes (Ivan Reitman, 1981) and action blockbusters like Top Gun (Tony Scott, 1985). Even the titles of Hollywood films were inspired by oldies, as evidenced by films like Sixteen Candles (1984), Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986), Walk Like a Man (Melvin Frank, 1987), and Johnny Be Good (Bud Smith, 1988), to name only a few. The persistent appearance of oldies in films primarily marketed to 1980s teenagers challenges the notion that rock soundtracks only (or primarily) produce feelings of generational belonging. The meanings conjured by oldies music in teen films like Sixteen Candles are different than those invoked by the soundtrack of Diner, and the extratextual information brought to bear on a reading of a 1950s song by a teenager in 1985 (who only knows the song as an oldie) will not be the same as that available to an aging baby boomer with living memory of the song’s original circulation. In other words, the nostalgic invocation of oldies music in 1980s teen-film soundtracks is not exclusively tied to personal memory or a shared generational past. Writing about the use of classical music in Raging Bull, Mike Cormack has argued that the proliferation of possible meanings for filmic music (cinematic, cultural and historical) creates “pleasures of ambiguity” for different film audiences (26). I would argue that a similar phenomenon is at play in the use of oldies music in Reagan-era teen films. We might think of this ambiguity as a result of the redefinition of rock music more generally in a time when rock and roll’s privileged position in the landscape of commercial American music was under direct assault from other emerging genres.

Old Time Rock and Roll and Insider Rebellion

In the 1970s, as the first rock and roll generation was entering middle age, a strain of American “roots rock” attempted to direct the genre back to its mythic origins. Bob Seger, a Detroit-area rocker who leapt into rock stardom with his 1976 album Night Moves, is emblematic of this movement. His album was lauded as “rock and roll in the classic mold: bold, aggressive and grandiloquent” and praised for its “songs of reminiscence” like “Night Moves” and “Mainstreet” (Rachlis). The opening track, “Rock and Roll Never Forgets”, attempts to mobilise the personal memories of audiences to reinvigorate the rock genre, imploring aging listeners to return to the pleasures of rock fandom with the refrain “come back, baby / rock and roll never forgets”.

Two years later, Seger returned to champion the value of traditional rock music with a song popularised by a teenpic. “Old Time Rock and Roll” was originally released to tepid response on the 1978 album Stranger in Town, but became a smash hit after its appearance in Risky Business. The song’s singalong chorus growls, “Still like that old time rock and roll / That kind of music just soothes the soul / I reminisce about the days of old / with that old time rock and roll”. This characterisation of the virtues of pre-psychedelic rock, to a large degree, corresponds to the descriptions of the appeal of oldies from radio station managers of the 1970s who championed oldies as “a great memory jogger” that would allow past “words or an incident [to] come flooding back” to adult audiences (Malcolm 21). Sentiments like these lead Shumway to argue that the “convention that popular songs call up for us memories of earlier periods in our lives is so powerful that we might be inclined to call oldies the tea-soaked madeleine of the masses” (40). And what sort of memories are being invoked? We might understand this sort of nostalgic affect, following Powrie, as a longing for “popular pleasures in a community context” (148). It is an image that recalls Benedict Anderson’s imagined communities, but “Old Time Rock and Roll” does more than revel in an imagined past—it also directly critiques contemporary music in the present.

While “Rock and Roll Never Forgets” encourages listeners for whom “sweet sixteen’s turned thirty-one” to “go down to the concert or the local bar”, in “Old Time Rock and Roll” (released just two years later) Seger stubbornly insists he would prefer just staying at home. In the opening lines, Seger demands “just take them old records off the shelf / I’ll sit and listen to them by myself”. In contrast to the exhortation to reinvigorate rock culture in “Rock and Roll Never Forgets” Seger’s later song has him cloistered in his living room, because “today’s music ain’t got the same soul”. When Seger critiques “today’s music” it is not rock that he dismisses but rather the emerging forms of music that threatened to displace it. In the second verse, Seger defiantly sneers, “Don’t try to take me to no disco / You’ll never even get me out on the floor … I like that old time rock and roll”. Seger’s loyalty to rock is, of course, in his own interest as a rock musician and songwriter. However, it is telling that Seger’s pledge of allegiance to rock takes the form of an explicit rejection of disco.

Rock historians describe the disco explosion of 1978 as “instantly polarising, especially to numerous rock fans who saw disco’s orchestrated and synthesised style of dance music as the antithesis to rock music’s ‘naturalised’ mode of authentic expression” (Cateforis, Rock History Reader 181). Beyond the commercial threat disco’s success represented, it also arguably destabilised white heterosexual masculinity as the locus of power in American popular music. The politics of disco in many ways worked against the established traditions of rock performance in the 1970s. When disco—a music genre and music scene that gave prominent roles to sexually empowered women and gay men (especially those from Black and Latin urban communities)—went mainstream, Alice Echols argues, it resulted in an atmosphere in which white men “felt themselves shoved to the sidelines by women, ethnic minorities, and gays … many rock fans believed disco was taking over, possibly even supplanting, rock” (Echols, Shaky Ground 163). This sense was only intensified in the wake of the commercial success of 1977’s Saturday Night Fever and its soundtrack, which became the best-selling album of 1978, and the top-selling soundtrack album of all time.

The vehement backlash against disco was demonstrated in events like Comiskey Park’s Disco Demolition Night, the parody “Do Ya Think I’m Disco?” and the graffiti slogan “Disco Sucks!” In a large percentage of these cases, the dismissal of disco took the form of a defence of rock. Thus, “Old Time Rock and Roll” appeared in Reagan-era soundtracks not just as a song but as a rallying cry. Rock and roll in this formulation did not represent the soundtrack of difference, as it did in the 1950s. Rather, the defence of “roots rock” in the 1970s often took the form of a resistance to difference, a form of insider rebellion that sought to secure the hegemonic position of the white male in U.S. society, and rock and roll in the entertainment industry.

Perhaps no film of the Reagan era symbolises this insider rebellion more than Risky Business,which took box offices by storm and made Tom Cruise a star in 1983. The film chronicles a week in the life of affluent teenager Joel Goodsen (Tom Cruise), a goodie-two-shoes high-school student who opens a brothel in his parents’ suburban home. In its most iconic scene, Joel dances to Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll” in his underwear. While Seger’s song was not an oldie per se, it does rely on a nostalgic conceptualisation of rock’s origins in the 1950s in order to reject its latter-day perversions into punk, new wave and disco. With this in mind, a reading emerges that suggests how a cultural notion of traditional rock performance affirms and celebrates Joel’s unfettered white bourgeois desires.

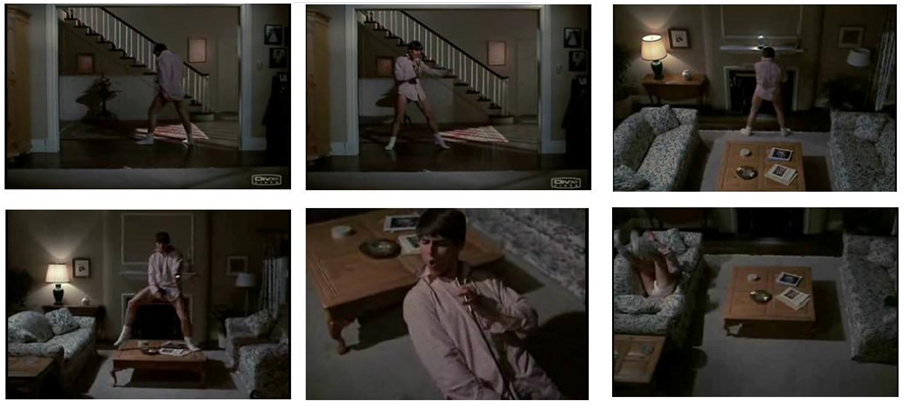

Joel (Tom Cruise) in the famous “Old Time Rock and Roll” sequence in Risky Business.

The sequence begins with extreme close-ups of Joel’s fingers manipulating the dials on his father’s expensive home stereo equipment. In the next shot, Joel slides across his parents’ polished hardwood floor in his stockinged feet, indicating his residual childish impulses as well as the absence of his parents from the space. The iconic costume suggests his unleashed boyish sexuality (in his tight white briefs) as well as the loosened upper-middle class morality (in the unbuttoned dress shirt). Using the domestic items of the house to aid in the fantasy (he employs a tall brass candlestick as an impromptu microphone), Joel takes pleasure in strutting about like a rock star (highlighted by the cheering crowd noise inserted into the sound design) and punctuating his lip-synching with high steps, hip jiggles, and fist-pumps in the tradition of rock and roll figures like Mick Jagger or David Lee Roth. Joel then swaggers into the tidy living room, exchanges the candlestick for fireplace broom and transforms into an air-guitar god. Finally, his energy becomes too strong for the rock fantasy and Joel ultimately flings himself down the couch and wiggles uncontrollably.

Gaylyn Studlar has convincingly argued that Joel’s dance sequence is representative of Hollywood’s efforts in the 1980s to “hegemonically secure male subjectivity [that] depends on the fundamental display of the male body, especially the youthful or youthful-looking male star” (173). However, a reading of this sequence might also emphasise Joel’s masculine sexual power as thoroughly contained within the domestic space of his middle-class home. It is only through Seger’s version of domesticated rock that Joel is able to loosen himself from bourgeois codes of behaviour and find an acceptable outlet of expression for his unruly desires. This form of “old time” rock simultaneously facilitates, contains and commodifies rock rebellion. In this sense, the sequence identifies rock music as a commodity that offers the pleasurable fantasy of outsider rebellion delivered to safe “insider” spaces. Simultaneously, “Old Time Rock and Roll” points backward toward a radically decontextualised politics of fun that can only be found in rock’s mythic Fifties origins (Grossberg 51).

Aside from its enormous influence and unquestioned status as a moment in which soundtrack, film and music video coalesced most effectively in Hollywood film, the dance sequence in Risky Business reveals how a particular framing of the class and racial politics of rock inherited from aging boomers was reinscribed in the body of the idealised Reagan-era teen. This is legible both in the scene’s visual elements but also in what Anahid Kassabian calls the “affiliating identifications” of the hit Seger song playing on the stereo. Unlike the classical Hollywood score, which aims to “draw perceivers into socially and historically unfamiliar positions”, Kassabian argues that film soundtracks featuring previously released music allow filmgoers to “bring external associations with the songs into their engagements with the film” (2–3). What is crucial about Kassabian’s work in this context is that audiences’ knowledge and familiarity with the music on film soundtracks (knowledge that is, as I’ve discussed, historically and culturally contingent) facilitate the production of a variety of readings of an individual scene. Boomers familiar with the racial and sexual politics of rock in the 1950s will have radically different “affiliating identifications” with Fifties soundtracks than Reagan-era teenagers who only know the songs as kinder, gentler oldies. The affiliating identifications of teen audiences to the concept of “old time rock and roll” in Risky Business aligns Seger’s insider rebellion with that of the bourgeois white teenager of the new generation, not the demographics and interests with which rock actually engaged in the historical 1950s.

Oldies Ventriloquism and Reagan-era Teens

Alignment, of course, does not imply duplication. The renewal of Fifties styles and texts in the 1980s does not technically reproduce the 1950s, but rather engages in repetition with a difference. By inhabiting an already-established form, the cover version opens up the same old songs to new and alternative meanings. Simultaneously, the 1980s teenager depicted on screen is transformed by the music of the baby-boom generation that he or she encounters. In the wake of Risky Business, a spate of scenes emerged wherein the body of the Reagan-era teenager becomes one of the primary sites and most prominent registers of the redefinition of the politics of Fifties rock and roll. The body could serve as an expression of new resistant youth cultures (as Dick Hebdige’s study of punk style and fashion illustrates), or display the persistence of forms of Fifties rock and roll culture (as the return of the “Loco-Motion” dance craze in 1987 suggests). Pretty in Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Adventures in Babysitting and The Lost Boys feature extended scenes in which teenaged characters mouth the words to oldies songs. Beyond providing a rationalisation for the inclusion of oldies on the films’ soundtracks, theses scenes are remarkable because of the way in which the baby-boom generation speaks through the body of the Reagan-era teenager, and the ways the 1980s teen can embody new meanings for recognised musical forms.

In a recent essay, Theo Cateforis argues that Pretty in Pink’s lip-synching scene—in which the lovelorn Duckie (Jon Cryer) passionately impersonates Otis Redding singing “Try a Little Tenderness”—enacts a gender performance that he dubs “karaoke masculinity”. This scene draws on the traditional gender binary in popular music wherein men serve as active performers and women serve as passive consumers and connoisseurs. Such performances are prevalent in the teen film genre, he argues, because “an established popular song communicates through its history and genre associations an accepted form of masculine identity. In a sense it has already articulated what the teen male wishes to say or become, in a way immediately recognisable to the audience” (“Rebel Girls and Singing Boys” 186). Duckie’s cry for “a little tenderness” is directed through an association with Redding largely because his own masculinity is too insufficient, juvenile or unreliable. This is a convincing reading, but does not account for the location of the scene. Duckie performs the song in TRAX, the independent/New-Wave record store, for an audience of only two employees: Andie (Molly Ringwald), the object of his affection, and Iona (Annie Potts), the store manager and hip older sister figure to Andie, with whom Duckie will eventually be coupled. As much as it augments his masculinity, Duckie’s performance also/alternatively functions as a display of cultural capital within the context of an independent record store, a sign that his musical knowledge of (and passionate attachment to) genres like soul goes beyond the doo-wop fare offered by most oldies stations.

A more neatly appropriate scene for Cateforis’s thesis may be in The Lost Boys, wherein the pubescent Sam (Cory Haim) gleefully sings along to Clarence “Frogman” Henry’s 1956 debut hit “Ain’t Got No Home” in the bath. Like Duckie, Sam is an ineffective adolescent, “a lonely boy” who has been abandoned by his father. Sam is not the only adolescent facing domestic instability—every teenaged character in the film “ain’t got no home”, in the sense of the traditional nuclear household. Even the titular Lost Boys vampire gang is motivated to attack local teens in their search for a mother to accompany their leader and father figure Max (Edward Hermann). One might read the film’s use of “Ain’t Got No Home” as an articulation of a longing for the patriarchal nuclear family popularly ascribed to the Fifties (the first verse plaintively cries “I ain’t got no father … ain’t got no home, I’m a lonely boy”), while the film simultaneously dramatises the consequences of the nuclear family’s breakdown (as it is Sam’s lack of a strong father figure that makes him vulnerable to bullying and subsequent vampire attacks). This reading, however, is only possible for those with “affiliating identifications” with the song as a specific text, rather than as a generic oldie. Alternatively, one might as easily read the song and its performance as complicating Cateforis’s thesis: far from augmenting Sam’s masculinity, the scene could be understood to highlight the arbitrary and performative nature of gender itself. In this reading the focus would be on the way Sam’s playful vocal performance fluctuates from falsetto to croak as the song’s narrative voice moves from “lonely boy” to “lonely girl” to “lonely frog”, and on the gender politics of falsetto in the tradition of African-American blues performance. In this way Kassabian’s notion of the contingency of soundtracks’ ideological operation becomes clear. Depending on one’s knowledge of the cultural significance of Henry’s song, or 1950s pop music, or the latter-day implications of oldies, one can extract radically different meanings from the combination of sound and image.

In Adventures in Babysitting and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, protagonists Chris (Elisabeth Shue) and Ferris (Matthew Broderick) do not perform oldies hits to compensate for inadequate sexual efficacy and power. Rather, their lip-synching draws on the established authority of dominant codes of sexuality to celebrate and reaffirm their adherence to them. In Adventures in Babysitting, The Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me” is heard before the first frame of the film is shown—the opening strains of the song play over the production credits. In the film’s first shot, Chris appears on camera lip-synching to the girl-group classic just as the vocals begin. The song tells the story of a girl who meets a boy at a dance, falls in love, gets married and lives happily ever after. Chris enthusiastically lip-synchs and dances to the song while preparing for her anniversary date with her boyfriend, aligning the fairytale love story of the song with her own personal fantasies. When the song concludes, the film reveals that her boyfriend is anything but a Prince Charming—he breaks the date with Chris and is eventually revealed to be a liar and a cheat. The song returns during the end credits, after Chris has successfully secured a new love interest. While the film’s explicit narrative tracks an arc of Chris’s increasing agency and self-confidence, the return of the song at the film’s conclusion (after she secures a new romantic interest) makes possible a reading wherein the song represents Chris’s desire not only to be located in a heterosexual coupling, but to be the passive object of romantic destiny—the one who is kissed, is wooed, is married. Her adventures in babysitting (in which she is a resourceful and independent leader, and agent of her own destiny) are, this reading of the soundtrack suggests, just an interlude.

By comparison, Ferris Bueller is not only an active sexual presence in his lip-synching scene; he is the centre of the universe. Ferris hijacks a float in Chicago’s Van Steuben Day parade, transitioning from a crooning faux-performance of Wayne Newton’s “Danke Schoen” to The Beatles’ version of “Twist and Shout”. Surrounded by leggy blondes, Ferris plays the part of the rock star, provoking the crowd of spectators to twist and shout themselves, as they erupt into spontaneous choreography. Men and women, young and old, black and white are united in celebration by the oldies hit, as embodied by the irrepressible Ferris Bueller. The scene became so iconic, in fact, that in 1986 “Twist and Shout” re-charted on the Billboard singles chart on the strength of the film. Ferris Bueller, in other words, inspired 1980s teenagers to listen to The Beatles with new ears, creating new affiliating identifications, based on Ferris’s charismatic egoism and hedonism, with a song that was over twenty-years old.

Whether it is giddy play-acting in the privacy of the bedroom or the bath (Adventures in Babysitting, The Lost Boys), an intimate performance among friends (Pretty in Pink) or a choreographed production that literally stops traffic in Chicago (Ferris Bueller), the spectacular display of teen bodies in these scenes draws on the allusive sexual and gender politics of the oldies music on the soundtrack. True, the sexual and gender politics foregrounded in these films is not necessarily based on the politics traditionally associated with these songs. That the teen bodies in these films are white bodies revises the racial politics of the Fifties rock-and-roll songs that they delight in performing. Yet this transformation must not be understood merely as another example of the white establishment co-opting African-American musical forms, not least because the music represented by oldies had itself been co-opted from the moment that Porky Chedwick started his career. Moreover, white middle-class youth in the 1950s embraced the traditions of black artists at least in part as a rejection of the conformity and containment of postwar bourgeois suburban life. Even in the early 1950s, pioneering rock artists like Chuck Berry were drawing substantial numbers of white suburban fans. “Facing a choice between the sterile and homogeneous suburban cultures of their parents or the dynamic street cultures alive among groups excluded from middle class consensus”, George Lipsitz explains, “a large body of youths found themselves captivated and persuaded by the voices of difference” (122).

When 1950s rock re-emerges in the 1980s as oldies, it still operates as an alternative to sterility and homogeneity—Ferris Bueller’s “Twist and Shout”, for example, serves as a testament to Ferris’s exuberant spontaneity and infectious charisma. In this scene, oldies work to define a politics of fun that is “defined by its rejection of boredom and its celebration of movement, change, energy … lived out in and inscribed upon the body” (Grossberg 114). However, it seems clear that oldies in these scenes do not represent a radical or emancipatory form of difference from dominant bourgeois values. In most cases, the combination of oldies music and teen films in the 1980s, as with the rejection of disco in favour of rock, represented a defence against difference, an affirmation of cultural insiders like Ferris Bueller. The song remains the same, but its cultural and ideological function, the politics of its nostalgia, are fundamentally contingent upon its location in extratextual and intertextual discourses.

The emergence of Fifties nostalgia as a socio-political trope of the Reagan era, the rejection of disco by figures like Bob Seger and the ventriloquising of 1950s rock on 1980s soundtracks are intertwined. The racially and sexually destabilising potential of genres like disco, glam, punk, new wave and hip-hop are rejected in favour of a notion of “old time rock and roll” in which white bourgeois males occupy the privileged centre. As a genre and a programming format, oldies attribute an Edenic innocence to American popular music before the British Invasion. Overlooking the actual socio-political realities of rock’s role in the 1950s, the idea of oldies posits a time when rock had no political or social agenda but simply served as good clean fun for (white, heterosexual) teenagers. Lip-synching scenes in Hollywood films of the Reagan era presented the body of the 1980s teenager as a space that could resolve the inherent contradictions that such a framing of rock produced, because this body could serve as a clean slate upon which the history of rock (and, indeed, the cultural history of the U.S.) could be re-written.

Whenever film and media studies have considered Hollywood soundtracks, the tendency has been to examine how the intertextual relations between song and film produce new or alternative readings of the diegetic action. As Kassabian argues, knowledge of a song, its lyrics, the performer or the history of popular music might provide an opportunity for viewers to extract additional or alternative meanings from a film. Music can provide commentary on characters, setting or onscreen action for those familiar with the history of the songs placed on the soundtrack. However, it is also important to recognise that the process can operate in the other direction: films can create new historical meanings for the music appearing on their soundtracks, and new cultural knowledge about the historical period from which they emerged. Lip-synching scenes vividly illustrate this potential. These scenes do not assume that their teenage audiences need to understand the complex social and political histories of 1950s popular music in order to make them legible. Rather, they rely upon and reiterate the discourses of Fifties nostalgia in the Reagan era, and as such produce new historical meanings for the songs on their soundtracks. They’re the same old songs, to paraphrase The Four Tops, but with different meaning as time goes on.

Notes

1. I differentiate between “the 1950s” as the chronological years 1950–59 and “the Fifties” as a potent socio-cultural construct produced in retrospect. Similarly, I use the expression “Reagan era” to signify not only the eight years when Ronald Reagan occupied the U.S. Presidency, but also the years in the 1970s when Reagan emerged as a powerful national political figure—stretching back to his first campaign for President from 1974–76. The arrival of Ronald Reagan on the national stage as an embodiment of neoconservatism marks a new period in U.S. history, a period coincident with the aftermath of the Vietnam conflict, a backlash against the Counterculture and Civil Rights, and the dismantling of Great Society government reforms.

2. For two examples of popular press coverage of Fifties nostalgia, see the cover stories “The Nifty Fifties”, Life, June 18, 1972 and “The Re Decade”, Esquire, March 1986.

References

1. Adventures in Babysitting. Dir. Chris Columbus. Touchstone Pictures, 1987. Film.

2. American Graffiti. Dir. George Lucas. Universal Pictures, 1973. Film.

3. Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 2006. Print.

4. Beatles, The. “Twist and Shout”. Comp. Phil Medley, Bert Russel. EMI London, 1963. Vinyl.5. The Buddy Holly Story. Dir. Steve Rash. Columbia Pictures, 1978. Film.

6. Cateforis, Theo. “Rebel Girls and Singing Boys: Performing Music and Gender in the Teen Movie”. Current Musicology 87 (2009): 161–90. Print.

7. ---. ed. The Rock History Reader. New York: Routledge, 2007. Print.

8. Cormack, Mike. “The Pleasures of Ambiguity: Using Classical Music in Film”. Changing Tunes: The Use of Pre-Existing Music in Film. Ed. Phil Powrie & Robynn Stilwell. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006. 19–30. Print.

9. Crystals, The. “Then he Kissed Me”. Comp. Phil Spector. London, 1963. Vinyl.

10. Disco Demolition Night. “Do Ya Think I’m Disco”. Perf. Steve Dahl. Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois. 12 July 1972. Performance.

11. Diner. Dir. Barry Levinson. MGM, 1982. Film.

12. Echols, Alice. Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010. Print.

13. ---. Shaky Ground: The Sixties and Its Aftershocks. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. Print.

14. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Dir. John Hughes. Paramount, 1986. Film.

15. Frith, Simon. Music for Pleasure: Essays in the Sociology of Pop. New York: Routledge, 1988. Print.

16. Goffin, Gerry, Carole King. “The Loco-Motion”. Dimension Records, 1962. Vinyl.

17. Grease. By Warren Casey and Jim Jacobs. Royale Theatre, New York. 1972–80. Performance.

18. Grossberg, Lawrence. “Is Anyone Listening? Does Anybody Care?: On ‘The State of Rock’”. Microphone Fiends: Youth Music and Youth Culture. Ed. Tricia Rose. New York: Routledge, 1994. 41–58. Print.

19. Happy Days. By Garry Marshall. ABC, 1974–84. Television.

20. Hebdige, Dick. “Subculture: The Meaning of Style”. Cultural Studies: An Anthology. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 587–98. Print.

21. Henry, Clarence “Frogman”. “Ain’t Got No Home”. Chess Records, 1956. Vinyl

22. Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”. New Left Review I.146 (1984): 53–92. Print.

23. Johnny Be Good. Dir. Bud Smith. Orion Pictures, 1988. Film.

24. Kassabian, Anahid. Hearing Film: Tracking Identifications in Contemporary Hollywood Film Music. New York: Routledge, 2001. Print.

25. La Bamba. Dir. Luis Valdez. Columbia Pictures, 1987. Film.

26. Lipsitz, George. Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001. Print.

27. The Lost Boys. Dir. Joel Schumacher. Warner Bros., 1987. Film.

28. Malcolm, Andrew H. “‘Oldies’ Are the New Sound As Radio Turns Nostalgic”. New York Times 17 July 1972: 1, 21. Print.

29. Marcus, Daniel. Happy Days and Wonder Years: The Fifties and the Sixties in Contemporary Cultural Politics. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004. Print.

30. Nadel, Alan. “Movies and Reaganism”. American Cinema of the 1980s: Themes and Variations. Ed. Stephen Prince. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007. 82–106. Print. Screen Decades.

31. Newton, Wayne, Perf. “Danke Schoen”. Capitol Records, 1963. Vinyl.

32. Oakes, Bill, Prod. Saturday Night Fever: The Original Movie Sound Track. RSO, 1977. Vinyl.

33. Palmer, William J. The Films of the Eighties: A Social History. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995. Print.

34. Peggy Sue Got Married. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. Tri-Star Pictures, 1986. Film.

35. Powrie, Phil. “The Fabulous Destiny of the Accordion in French Cinema”. Changing Tunes: The Use of Pre-Existing Music in Film. Ed. Phil Powrie & Robynn Stilwell. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2006. 137–51. Print.

36. Powrie, Phil, and Robynn J. Stilwell, eds. Changing Tunes: The Use of Pre-existing Music in Film. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Pub Co, 2006. Print. Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series.

37. Pretty in Pink. Dir. Howard Deutch. Paramount, 1986. Film.

38. Rachlis, Kit. “Bob Seger—Night Moves”. Rolling Stone 13 Jan. 1977.<http://web.archive.org/web/20080107220556/http://www.rollingstone.com /artists/bobseger/albums/album/259184/review/6067582/night_moves>. Web. 30 Sept. 2009

39. Rampage. Bally Midway, 1986. Video Game.

40. Redding, Otis, Perf. “Try a Little Tenderness”. Volt/Atco, 1966. Vinyl.

41. Risky Business. Dir. Paul Brickman. Warner Bros., 1983. Film.

42. Saturday Night Fever. Dir. John Badham. Paramount, 1977. Film.

43. Seger, Bob. “Mainstreet”. Night Moves. Capitol Records, 1976. Vinyl.

44. ---. “Night Moves”. Night Moves. Captiol Records, 1976. Vinyl.

45. ---. “Old Time Rock and Roll”. Stranger in Town. Capitol Records, 1979. Vinyl.

46. ---. “Rock and Roll Never Forgets”. Night Moves. Capitol Records. Vinyl.

47. Shumway, David R. “Rock ‘n’ Roll Sound Tracks and the Production of Nostalgia”. Cinema Journal 38.2 (1999): 36–51. Print.

48. Sixteen Candles. Dir. John Hughes. Universal Pictures, 1984. Film.

49. Stand By Me. Dir. Rob Reiner. Columbia Pictures, 1986. Film.

50. Stripes. Dir. Ivan Reitman. Columbia Pictures, 1981. Film.

51. Studlar, Gaylyn. “Cruise-ing into the Millenium: Performative Masculinity, Stardom, and the All-American Boy’s Body”. Ladies and Gentlemen, Boys and Girls: Gender in Film at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. Murray Pomerance. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001. 171–83. Print.

52. Top Gun. Dir. Tony Scott. Paramount, 1986. Film.

53. Walk Like a Man. Dir. Melvin Frank. MGM, 1987. Film.

54. Weigle, Ed. “Porky Chedwick: Radio’s Most Ignored Pioneer and the First DJ to Spin Oldies”. Goldmine 27.21 (2001): 48, 50. Print.

55. Weird Science. Dir. John Hughes. Universal, 1985. Film.

Suggested Citation

Dwyer, M. D. (2012) 'The same old songs in Reagan-era teen film', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 3, pp. 5–18. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.3.01.

Michael D. Dwyer is Assistant Professor of Media and Communication at Arcadia University, teaching courses in film, media studies and cultural studies. His book manuscript, Back to the Fifties, centres on the function of nostalgia in popular media, evolving practices of allusion, citation and quotation, and their relationships with history and cultural memory in the Reagan era.