The Gendered Politics of Sex Work in Hong Kong Cinema: Herman Yau and Elsa Chan (Yeeshan)’s Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale

Gina Marchetti

The legs of Suzie Wong (Nancy Kwan) vie with Bruce Lee’s lightning kicks to represent Asia’s “world city” of Hong Kong on global screens. [1] Cold War associations of the port’s sex industry with American GIs on R&R linger as Suzie Wong remains part of the popular imagination of the former British colony. Countering Hollywood and responding to its Orientalist characterisation of the territory’s demimonde, local filmmakers take up the subject of sex work from more nuanced perspectives. Hong Kong films investigate prostitution as a social problem, as an index of women’s economic exploitation, as a window onto the world of sexual minorities, as an allegory of capitalism more generally, and, of course, as erotica (pornography literally means writing about prostitutes).

Working in conjunction with director Herman Yau, Elsa Chan has cowritten two features about women in the Hong Kong sex industry—Whispers and Moans (性工作者十日談, 2007) and True Women for Sale (性工作者2 我不賣身·我賣子宮, 2008). The Chan-Yau films differ from other cinematic renderings of the territory’s sex industry in their reliance on the testimony of sex workers for inspiration, the inclusion of activists as characters engaged in agitating for change in the sex industry, and the presence of an implicit feminist voice as a point of critique. While other films function as allegories, exposés, or exploitation, Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale include similar elements, while branching out into terrain more often associated with documentaries or activist videos produced by NGOs.

On screen, prostitution provides a wealth of symbolic associations going beyond the actual circumstances of women’s lives on the streets. Filmmakers over the years portray the motion picture medium as what Rainer Werner Fassbinder has called a “holy whore”, and directors such as Jean-Luc Godard feature sex work as a metaphor for the way the motion picture industry entertains its own clientele as filmmakers turn human desire into cash. Not only men, but women filmmakers too, view prostitution from many angles, although arguably through a different lens. Women’s films on prostitution include silent films such as The Red Kimona (Walter Lang, 1924), produced and most likely co-directed by Dorothy Davenport Reid (wife of Wallace Reid), and co-written by Dorothy Arzner and Adela Rogers St. John; Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls (1986), among many others. The raw dramatisation of the exchange of female bodies in film as well as the elusive promise of emancipation through sexuality can promote a feminist conversation about the meaning of women’s liberation under capitalism. Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale take up this cinematic conversation to add Hong Kong women’s voices to debates involving the female body, the sex industry and commercial cinema.

Prostitution on Chinese Screens

Chinese filmmakers since the silent era have made classic films on this topic: for example, The Goddess (Wu Yonggang, 神女, 1934) and Street Angel (Yuan Muzhi, 馬路天使, 1937). The fact and fiction of mainland Chinese women’s entry into prostitution has grown exponentially since the end of the Mao era, reflecting broader economic and political changes in the PRC that have intensified tensions between the sexes in general. Lisa Rofel chronicles these enormous changes and summarises this ideological transformation as follows:

[A] postsocialist allegory of modernity tells a story of how Maoism deferred China’s ability to reach modernity by impeding Chinese people’s ability to express their gendered human natures. The allegory is an emancipatory story, holding out the promise that people can unshackle their innate gendered and sexual selves by freeing themselves from the socialist state. It is also a rejection of Maoist feminism. In popular discourse, Maoist feminism is blamed for attempts to run men and women into unnaturally gendered beings. Women are said to have become too masculine, while men were unable to find their true masculinity … the 1990s in China witnessed a historically specific self-conscious enthusiasm for coherence through the search for a novel cosmopolitan humanity. (13)

Women often cobble together this new identity through consumer products and the post-feminist fictions that circulate about what it means to be a “woman of the world”.

David Harvey acknowledges the “gender consequences” of the new economy:

All of the trappings of Westernization are there to be found, including transformations in social relations that have young women trading on their sexuality and good looks at every turn and cultural institutions (ranging from Miss World beauty pageants to blockbuster art exhibits) forming at an astonishing rate to create exaggerated versions, even to the point of parody, of New York, London, or Paris. What is now called “the rice bowl of youth” takes over as everyone speculates on the desire of others in the Darwinian struggle for position. The gender consequences of this have been marked. (147–8)

Other scholars also note Chinese women’s struggle to succeed in this new economic environment. Leta Hong Fincher, for example, discusses the travails of women in post-Deng China in considerable detail.

As consumerism takes hold, women tend to be under increased pressure to find a desirable match by purchasing the latest fashions, cosmetics, and diet regimens. Often, a pretty body can be exchanged for a ticket to a better life, and even women who would never consider sex work resort to cross-border marriages, transnational extramarital affairs or interracial romances as a way out. The body provides access to global desires that transcend the limitations of the nation. Guo Xiaolu’s She, a Chinese (中國姑娘, 2009) about a young Chinese woman using her sexuality to survive in Great Britain offers simply one case in point. Guo, in fact, has a particular fascination with sex work. In her novel, A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers, she relates her protagonist’s reaction (in first-person, broken English) to seeing a live sex show in England as follows:

While I standing there watching, I desire become prostitute. I want be able expose my body, to relieve my body, to take my body away from dictionary and grammar and sentences, to let my body break all disciplines. What a relief that prostitute not need speak good English. She also not need to bring dictionary with her all the time …

The great decadence is attracting me.

The great decadence is seducing me like a magnet. (138–9)Other women take note of the appeal as well as the stigma involved in China’s burgeoning sex trade with stories set before as well as after 1949 (for example, Li Shaohong’s Blush, 紅粉, 1995). [2]

When the mainland prostitute hits the supposedly open market of Hong Kong, the impact of neoliberalism, the retreat of the nation-state from the regulation of labor relations and the transnational flow of capital becomes even clearer. Films made since Hong Kong’s change of sovereignty from British to Chinese rule in 1997 use the prostitute to spotlight the impact of cross-border economic and political changes. Mainland sex workers, for example, allegorise the relationship between the People’s Republic of China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Fruit Chan’s Durian, Durian (榴槤飄飄, 2000) focuses graphically on the hard work involved in the sex trade as it chronicles the Hong Kong sojourn of Yan (Qin Hailu) from northeastern China, as well as her return to her hometown. [3] Chan’s Hollywood, Hong Kong (香港有個荷里活, 2001) also features a mainland prostitute in Hong Kong, [4] who takes advantage of several generations of lustful males in one family to help satisfy her own desire to move on to Hollywood, California. She tarries at Plaza Hollywood on the edge of the rundown neighbourhood of Tai Hom, which had been a site of early film production in the colony (The Conservancy Association), to pursue her own version of the American Dream by using her body as a means to accrue the necessary capital for travel. The young mainland prostitute adrift in the world provides a floating signifier of female sexuality for sale. A migrant from the countryside in China looking for cash in the city and afloat in the Chinese diaspora, she represents the displaced worker exploited by the new “service” economy, looking for a way to get rich and be “glorious”, as Deng Xiaoping advised (qtd. in Whitely).

In many Hong Kong films, the prostitute emerges as a figure of both pity and fear—an emblem of transnational neoliberalism out of control—since the prostitute lives at the boundary between the legitimate and illicit economy. [5] In the HKSAR, prostitution is not a crime, but procuring and living off the proceeds from sex work are illegal. Many sex workers, then, live on the edges of the criminal underworld and are subject to harassment by the police. As a consequence, prostitution tests the limits placed on women’s sexuality, with a balancing act between domestic demands and the need to survive in an uncertain economy. In Samson Chiu’s Golden Chicken (金雞, 2002) and its sequel Golden Chicken 2 (金雞2, 2003), Sandra Ng plays Kam, a local prostitute who narrates the story of her life against the backdrop of Hong Kong’s economic rise through the 1980s and 1990s and fall during the SARS epidemic. Kam (whose name means “gold”) clearly represents the “spirit” of Hong Kong—entrepreneurial, always on the make, hungry for quick cash, but willing to sacrifice for others. With Andy Lau playing himself to promote Hong Kong as a place for exceptional service and commitment to the “genuine” article, Kam takes the government campaign to heart as she grunts and sweats her way past competition from mainland sex workers and the impact age has on her ability to make money.

While Kam represents Hong Kong as an old whore, other films focus on the sex industry in a different way. Hong Kong women filmmakers have been attracted to the subject, for example, to explore some of the feminist ramifications of looking at sex as a commercial transaction. [6] Yau Ching’s Ho Yuk: Let’s Love Hong Kong (好郁, 2006) features several lesbians involved in various aspects of the sex trade—from cybersex to selling pornographic DVDs and sex toys on the street. Scriptwriter Elsa Chan (also known as Yang Yeeshan, Yeung Yee-shan and Chan Yeeshan) provides another case in point with her collaborations with director Herman Yau.

The two films discussed in this article are loosely based on Chan’s investigations into the lives of Hong Kong sex workers published in English as Whispers and Moans. [7] Trained as an anthropologist with a doctorate in Japanese Studies from the University of Hong Kong (2007), Chan draws on a rich ethnographic understanding of sex work in the territory. [8] Director Herman Yau brings his own academic interest in Hong Kong culture to the project. Although best known for his Category III exploitation films such as The Untold Story (八仙飯店之人肉叉燒飽, 1993) and Ebola Syndrome(伊波拉病毒, 1996), Yau also boasts impressive academic credentials (he received a master’s degree in Cultural Studies from Lingnan University in 2008 and a doctorate from the same institution in 2014). Many male-female filmmaking teams operate in Hong Kong cinema (for example, Clara Law and Eddie Fong, Mabel Cheung and Alex Law); however, a better-educated pair may be hard to find. The Western names of the key prostitutes in Whispers and Moans, for example, Nana and Aida, point to French literature (Zola’s novel), New Wave cinema (Godard’s My Life to Live (Vivre sa vie: film en douze tableaux, 1962)) and grand opera (Verdi), and testify to the cultural capital that went into this Category III production (restricted to adults at or over the age of eighteen).

Chan and Yau, in fact, gravitate toward the salacious with an eye toward social change and political critique. Like their earlier collaboration From the Queen to the Chief Executive (等候董建華發落, 2001), Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale look at the sensational (youth murders, prostitution) with a commitment to understanding and perhaps remedying injustice. In fact, the issue of justice and women’s role as exploited victims and potential agents of change link Elsa Chan’s scripts to the interests of other women filmmakers currently working in the HKSAR. It is no coincidence, for example, that Chan also scripted Ann Hui’s All About Love (得閒炒飯, 2010), which is director Hui’s most explicit treatment of female sexuality and gender inequality, albeit in the guise of a queer romantic comedy about bisexual single mothers. Herman Yau also returned to the subject of sex work in Asia in the feature Sara (雛妓, 2014), partnering with another female scriptwriter Erica Li Man.

Given that cinema is a collaborative medium, it proves difficult to attribute authorship to any specific aspect of a film. For example, in the Chan-Yau collaborations, a tension exists between the voice and visual representation of the sex workers that opens the films up to critical reflection on gender and sexuality in Hong Kong’s rapidly changing political and economic environment. The eye for exploitation and melodrama vies with the ear for political discourse and cross-border dialogues involving the tough issues of gender inequality, sexual commerce, and violence against women. In fact, the films gesture toward a feminist intervention into the shadow economy between transnational capitalism and the socialist marketplace at the border between the PRC and the HKSAR.

Feminist Frames

One of the striking features of Whispers and Moans is the role the female activist/ social worker plays in voicing explicitly feminist perspectives on sex work. Elsie (Yan Ng), a feminist advocate for the rights of sex workers, frames the various stories told by and about the prostitutes in the narrative. In many ways, Elsie stands in for Elsa Chan, since the character’s name is based on a diminutive of the scriptwriter’s English name; however, this social activist wants to go beyond journalistic exposé or cinematic exploitation to play a role in transforming the way in which the prostitutes view themselves. Indeed, as Sebastian Veg points out, the film presents conflicting views about the socio-political position of prostitution. He observes,

the “girls” in the film come across as both ordinary people and as individuals too strong to tally with a unifying discourse on their work or their beliefs. In this way, at the end of the “ten days,” the viewer does not know whether to feel empathy with this modern proletariat or to envy it, whether to make it an object of study or of political activism. Rather than Elsie’s objectifying but overly idealistic gaze, it is cinema which in this case lends dignity and charisma to the characters it depicts. (88)

Whispers and Moans takes up a range of voices with the activist Elsie providing only one among many.

Figure 1: Elsie (Yan Ng) introducing her organisation to sex workers on the street in Whispers and Moans (Herman Yau, 2007). Mei Ah Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

The sex business serves as a gender battleground, and Elsie attempts to take up the banner as a representative of the “Rights and Benefits of Sex-Workers’ Union”. She positions herself on the street in front of a club that pairs bargirls Nana (Mandy Chiang), her sister Aida (Monie Tung) and Happy (Chan Mei-hei) with clients under the management of “mama-sans” Coco (Athena Chu) and Jenny (Candy Yu), who oversee the transactions and take a percentage. Since the actual sex acts take place offsite as “takeout orders” at hotels that rent rooms short-term, the madams fall beyond the legal definition of pimp, but barely. Elsie focuses on this all-female environment in a gender-polarised industry. Female sex workers and male clients dominate here (and in the industry at large); however, a parallel club provides gigolos such as Tony (Patrick Tang), who primarily service wealthy housewives and fellow sex workers who prefer a “boyfriend” in the same business. As an occasional customer, Tony asserts his male prerogative to humiliate women. Although he expresses tremendous tenderness in his relations with his transgendered lover Jo (Don Li), Tony admits to feeling the overpowering need to brutalise female prostitutes to compensate for his own subordinate status within the sex industry as a gigolo.

Saving up for a sex change, the preoperative Jo works the street and occupies a marginal realm between the male and female divide in the industry. However, even though Elsie confines herself to the female sex workers, the critique she represents of the male-dominated hierarchy of the trade functions equally well to explain Tony and Jo’s subordinate positions within the business. The whore is feminised (subordinated) even if the prostitute is not always biologically female: Whispers and Moans proffers a sympathetic space for the consideration of LGBT/queer sexuality as well. Even when women appear to have enough cash to free themselves of the sex-gender hierarchy, they end up in roles defined and controlled by men—stigmatised as pitiable and dependent single mothers, conniving gold-diggers or other types of prostitutes on a sliding scale of misogyny and patriarchal privilege.

Figure 2: Elsie continues her campaign in a restaurant in Whispers and Moans. Mei Ah Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

Elsie intervenes to “raise the consciousness” of these prostitutes as women as well as workers (Figure 1). Her campaign parallels some of the actual efforts of the Hong Kong sex worker advocacy group, Zi Teng, meaning “purple vine”. This group has produced its own film about the sex trade in Hong Kong, Sisters and Ziteng (King-chu Kong, 姐姐妹妹與紫藤, 2006), which deals with many of the same issues exposed in Chan and Yau’s film. Like comparable organisations elsewhere, Zi Teng has several goals including educating the general public about sex work as well as being “actively engaged in building contacts with sex workers, providing them information on health care services, their legal rights and other resources” (“About Us”). Elsie introduces the work of her fictitious organisation to a group of sex workers eating in a local hotpot restaurant as follows (Figure 2):

Ours is the first volunteer organization defending the rights and benefits of sex workers in Hong Kong. Those political parties calling for human rights are actually humiliating the sex workers. They mislead people, insult the sex workers in exchange for votes. Sex workers should stand up to fight for their rights.

The camera moves around the table as the women scrutinise Elsie’s business card and listen to her speech. The location shooting, fluid camerawork and ambient sound mimic an observational documentary style, lending a feeling of immediacy and authenticity to the exchange. One woman chimes in. She has misunderstood the term “sex worker” and hears it as “sex toy”, which sounds similar in Chinese. Elsie, now sitting at the table with the women, explains that sex workers have dignity, make their own living and that a sex toy is an object for people to play with. Elsie goes on to condemn male-dominated society, but Jenny, wanting to eat in peace, drives her away from the dinner table.

In the fictional world of Whispers and Moans, a naïve crusader plays better dramatically than a seasoned social worker, lawyer, political advocate, labour activist or psychological counsellor. However, even though Elsie voices many overly idealistic notions about the respect due to prostitutes, she still provides a cinematic platform for the expression of the key issues involved in sex work from a progressive, feminist perspective. These include poor treatment by clients who may be violent or refuse to use condoms, harassment by the police who entrap women under laws against soliciting, the lack of attention to sex workers’ needs by callous social workers and, of course, the impoverishment of women trapped in a system that absolves their male customers of the social stigma that they as women inevitably suffer. Elsie distributes condoms, tries to educate the women about sexual hygiene (most know their infectious diseases, but have enormous difficulty avoiding contagion), and attempts to instil in them a sense of respect for the value of their own labour.

Although the word “union” does not come up in the film, the right of prostitutes to organise and collectively petition for changes in the laws governing their profession remains an unspoken political option that many groups advocate. In the case of Whispers and Moans, the direct confrontation of labour issues takes a backseat to the demands of melodrama. Issues that have a public component (the right to demand the use of condoms, to take legal action against violent clients, to compete openly for services or to make collective decisions about rates) hide behind private squabbles and domestic dramas. The stakes may be higher and the stigma greater, but labour issues remain the same in the brothel and the factory. Cross-border competition, lack of collective bargaining power, exploitation of workers living in fear of losing their sole means of employment, and increasing pressure to conform to a global standard of “service” plagues workers in all industries—not just the sex trade. [9] Elsie sees these women as workers and their madams as small businesswomen up against the glass ceiling of their profession. As managers rather than owners, they represent a middle-class within the business who have relatively little power in the face of potent real estate interests (as evidenced by the eventual shuttering of the club due to rising rents) and the demands of their male clients (who often abuse the bargirls).

Elsie challenges the women to look more clearly at themselves and their job. Although shunned at first, she manages to win the trust of the prostitutes to the extent that she can create a forum for discussion of their attitudes toward the sex industry. While Elsie appears to believe that sisterhood is powerful and that a little consciousness-raising can go a long way in giving the women self-respect, the prostitutes whom she hopes to rally have a very different conception of their lives. They dream of “good marriages”, stable homes for their children, relief from poverty and respected positions within their communities after retiring from prostitution. In fact, Whispers and Moans serves as an illustrated rebuttal to Elsie’s argument by dramatising the ways in which capitalist reality limits the efficacy of feminism in reforming the rules governing women’s sexuality.

Sexual Exchange Value: Production and Consumption

Whispers and Moans demonstrates that the sex industry operates as a business much like any other with a sense of professionalism, putative ethical standards, managerial and labouring classes, finance, marketing, and customer service operations and a career path with the possibility of retirement as a goal. Clothing immediately indicates role and status: the madams wear dark business suits with prim white blouses; the bargirls sport cocktail dresses; street girls wear tight jeans or miniskirts and revealing tops. Women working out of their own single rooms need only a towel or bathrobe to ply their trade. The hierarchy remains rigid, and the film systematically sets forth the various ways in which the sexual marketplace keeps women from breaking free of the system. In addition to suffering exploitation as workers, they often become pawns in a consumer culture as well through their involvement with the drug trade, gambling, high-interest loans, and other triad operations. The pressures of consumerism, in fact, permeate the film. This reflects Elsa Chan’s ethnographic research, since she has “met teenage girls who entered the business just to get a new Nokia” (qtd. in Carroll 26).

At the lowest rung, Aida, a drug user, slides down the economic ladder as the value of her body diminishes because of her addiction. She moves from the relative comfort of the bar, which serves well-to-do men, to the one-woman brothels of the lower order. Because of Hong Kong laws against bordellos, women who service proletarian men often work out of apartments in poorer neighbourhoods. However, when a client sees needle marks on Aida’s arms, the owner of the flat throws her out onto the street. As a streetwalker, Aida slides into the illegal end of the business, since soliciting is against the law, and lands on the bottom rung of the trade. At this point, her sister Nana intervenes, locking her in an apartment, forcing her to withdraw from drugs.

Nana represents the other end of the industry. A beauty in high demand, she has the option to bid farewell to the business and marry her childhood sweetheart. She leaves him without explanation—ducking out of the fancy restaurant where he proposed and throwing her cell phone in the trash—ostensibly because (as she confides to Elsie) she fears running into former clients at the large wedding banquet her boyfriend has planned. Shame stands in her way, and, perhaps, a sense of familial obligation to Aida. A flashback, reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s classic short The Sandwich Man (兒子的大玩偶, 1983), shows the girls shamed by their father’s job as a human dartboard dressed as Santa Claus. They discover that he humiliated himself in order to buy his daughters’ Christmas gifts, and they vow to make money in order to bring their family out of poverty, which paves the way for their entry into the sex trade as under-aged prostitutes. As the flashback indicates, stigma extends beyond the sex trade into other aspects of the lives of the working poor in Hong Kong, who must use their bodies to eke out a meagre living. Very traditional Chinese values such as filial piety work in concert with predatory business practices inside and outside the demimonde to keep poor women at the economic margins.

The film slips between class struggle and gender injustice in a parallel plot thread featuring Coco, one of the managers at the club. She represents the opposite pole of the industry as a former prostitute who now pimps other girls. However, even in this managerial role, she has difficulty supporting herself, her mother and her daughter, so Coco lives off her married and engaged boyfriends as a professional mistress. One of these men develops a severe case of tertiary syphilis, which seems to have affected his nervous system and given him dementia. As she struggles to find out the exact cause of his illness and, hoping for some compensation, she encounters his other lover Jo, who still cohabits with the afflicted man. During the course of her diagnosis, she realises she may have infected her young daughter through bacteria in her tears and takes the hysterical child into the clinic to check for venereal disease.

When Coco’s other lover plans to get married, she struggles to hang on to as much as possible financially before he leaves her. When she asks him to wear a condom, he claims “not to be in the mood”, asking her to return an expensive wristwatch instead—ostensibly to help with the cost of his impending nuptials. However, he gives the watch to Happy, one of the mainland prostitutes, in exchange for her services during his bachelor’s party. Coco, of course, sees the watch and punishes Happy by urinating on her in a swimming pool—threatening her with syphilitic contagion. Nevertheless, in an interesting narrative twist, Happy returns the watch to Coco, who gives it back to the mainland woman; the two reconcile before the club closes and Happy goes home to the PRC.

Troubling Sisterhood: The Mainland Prostitute

Happy has the most to gain, but also quite a lot to lose, as she plies her trade in the HKSAR. Married with ambitions of upward mobility across the border, she sees the Hong Kong streets as a place to make as much money as possible in the informal, but not criminal, economy. However, because of her accent and general demeanour, Happy provides an easy target for the police. At one point, officers accuse her of soliciting and try to get a local man to bring charges against her, but Elsie comes to her aid and the police back down. The two outsiders join forces, and Happy becomes Elsie’s entrée into the club, where she gains the confidence of the other prostitutes.

Several of the women, in fact, are from the mainland, which is reflected when Elsie switches from Cantonese to Mandarin, in her first conversation with prostitutes in the film as the activist explains the reason behind the condoms she provides to them free of charge. Later, in the locker room, the all-female inner sanctum at the club, several of the mainland women open up to Elsie about their ambitions. As Elsie takes notes, one woman talks about how the people in her hometown in Dongbei (north-eastern China) pretend not to know what the women do in Hong Kong. A woman from Sichuan talks about the loyalty of the men from her province who stay true to their wives prostituting themselves in the south.

Happy serves as the model worker for the other women from the PRC—a post-socialist update of the “iron girls” of the Mao era. She prides herself on her “professional record”, which she has kept during her seven years in the Hong Kong sex trade as a “healthy and happy whore”, without gambling, smoking, drinking, doing drugs, or keeping a “boy toy”, always using a condom and never getting depressed. She asks, “What other whore is as strong-willed as me?” and claims, “It’s the professional spirit that keeps me from going crazy.” Moreover, Happy’s work ethic takes her farther in the sex business than the Hong Kong-born bargirls. Her coworker speaks about the loyalty of Happy’s husband, who looks after her kids without spending any of the money his wife sends back home. Instead, he has funnelled the profits into a primary school under the auspices of the Communist Party–controlled county office, with himself as principal and Happy as vice-principal. The Hong Kong sex trade in this case fuels the development of the educational infrastructure in the mainland. During the exchange between the mainland women and Elsie, a cutaway shows Nana listening, clearly unhappy, since unlike her mainland counterpart she has no prospects to retire to a better life.

Whispers and Moans downplays the antagonism between the mainland and local prostitutes, but several references throughout the film, going beyond the actual pissing scene, hint at the depth of the anxiety surrounding the mainland sex workers. Clients from Japan claim that prices are lower and services are better across the border in Shenzhen, while the closing of the club at the film’s conclusion indicates a more general fear that mainland Chinese competition may destroy more than Hong Kong’s sex industry. An earlier generation of the local women, for instance, would have had the opportunity to work in manufacturing. However, since the factories moved across the border to take advantage of cheaper labour and fewer restrictions, this segment of the economy has vanished. Elsie’s insistence on the dignity of work rings a false note when jobs available to working class women evaporate, leaving even less desirable alternatives on the streets. Elsie never articulates the impact of globalisation on the sex workers she champions, a blind spot that reduces her stature within the film as a potential voice of political change.

“My Womb Is Not For Sale”

This alternate title for Whispers and Moans’ companion piece, True Women for Sale, quotes a line of dialogue from the film’s concluding scene. Wong Lin-Fa (Race Wong), a mainland bride, married a man from Hong Kong on the rebound from a failed engagement to a social climber who grabbed the chance to leave China unencumbered. Now widowed with three young children, Wong encounters a friend from her hometown, who has come to Hong Kong to pursue her fortune. Looking down on the newcomer, the mainland widow takes pride in avoiding prostitution to earn her living; however, her friend retorts that she may take money for sex but her “womb is not for sale”. A galaxy of issues involving women’s sexuality and reproductive capabilities circles around this phrase. In fact, global media take up Chinese women’s wombs on a routine basis with items about the one-child policy, gender-specific abortions, surrogate motherhood, and maternity tourism. Mainland Chinese films such as female director [10] Xue Xiaolu’s Finding Mr. Right (北京遇上西雅圖, 2013) and Yu Zhong’s Be a Mother (母語, 2011) deal with some of these concerns, while Hong Kong woman filmmaker Kiwi Chow explores similar territory in A Complicated Story (一個複雜故事, 2014).

The mother/whore dialectic provides the structure for True Women for Sale as well, turning the tables on assumptions of the relative virtue and value of each role. However, as the film compares the life of Wong to a local Hong Kong prostitute with bad teeth, Lai Chung-Chung (Prudence Liew), the film’s sympathy for Lai over the gold-digging widow may have more to do with the women’s right of abode in the HKSAR than with their choice of livelihood. The widow and the prostitute live in the same tenement building, and Chung-Chung tries to befriend the struggling mother from across the border. Repulsed by her neighbour’s line of work, Wong remains detached, struggling to collect insurance money from her in-laws, to give birth to her twins (which she does on a public bus) and to establish her right to stay in the territory with the help of conniving insurance broker Lau Fu-Yi (Anthony Wong).

Against the backdrop of a local press that features ads calling for the mainland “locusts” to go home and not deposit their progeny in Hong Kong, True Women for Sale seems not to engage adequately with the complicated issues broached by the narrative. The Hong Kong legislature navigates between public opinion and the dictates of Beijing to handle the demands of families divided by the border, the pregnant women clogging the obstetrics system in their rush to give birth in the territory and the various debates involving the relaxation of restrictions on immigration.

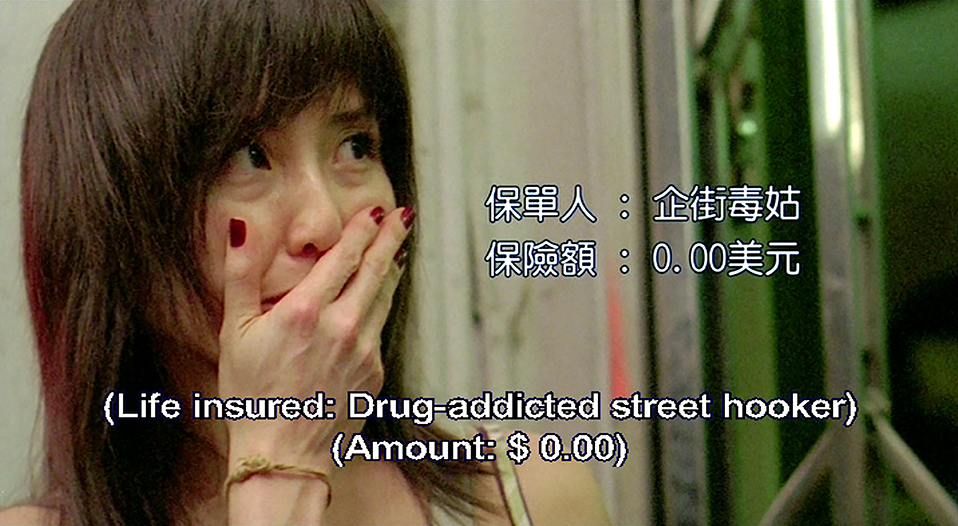

Figure 3: A prostitute’s life without value—Lai Chung-Chung (Prudence Liew) in True Women for Sale (Herman Yau, 2008). Mei Ah Entertainment, 2008. Screenshot.

Part of the problem in the sequel to Whispers and Moans lies with the decision to replace Elsie with other characters that provide a concerned outsider’s perspective on the demimonde. While insurance salesman Lau keeps a close eye on Wong, whom he hopes will use some of her cash to buy a policy, he does not advocate for any particular change in attitudes or legal statutes. When Lau encounters other characters in the film for the first time, a title appears on screen showing his mental calculation of the value of any insurance policy he may be able to sell to them (Figure 3). Although this makes the connection between human bodies and cash value graphically clear, it does not open up a platform for discussion within (or arguably outside) the diegesis. Similarly, a male photographer Chi (Sammy Leung) and his female colleague, journalist Elaine (Toby Leung), do not play the same activist role as Elsie in Whispers and Moans as they investigate the life of prostitute Lai. Although Chi admires Lai’s selflessness when he captures a picture of her saving a young boy from a speeding vehicle, he does not voice any political concerns about her circumstances. When Elaine interviews her, the journalist’s frustration becomes evident as the prostitute does not provide the candid information she expects for the money paid. Sister Kot (Monie Tung) comes closest to taking up Elsie’s banner when she asserts that she “respects” prostitutes. However, this nun remains on the margins of the plot, saying little and doing less. While showing the inadequacy of healthcare, childcare and other social welfare institutions, the film reduces the role of the advocate to a glimpse of the fleeting figure of a sympathetic nun, while the political activist stays out of the picture.

Figure 4: Elsie’s “revolutionary” call to take to the streets for political action in Whispers and Moans. Screenshot.

Conclusion: Taking It to the Streets

Although Elsie might seem naïve to pontificate about the nobility of sex work in Whispers and Moans, much of what she says makes sense. On the night before the escort club closes, she stands on a table in the locker room and delivers this speech (Figure 4):

Prostitution is the world’s oldest business. No country or ruler can eliminate sex deals. The permanence of prostitution proves the fact that there’s a demand for sex services in our society. But male-dominated society culture [sic] has been pressuring sex workers for thousands of years, and at the same time prejudiced [sic] against them. Therefore, the sex workers’ revolutionary purpose of our association [is] to eliminate sex workers’ negative image, so our society won’t be prejudiced against them anymore and they will respect their jobs more. For the sake of rehabilitating prostitutes, next month there will be a demonstration to defend their rights and benefits. I hope all of you will come to join us to defend your future.

Elsie’s “revolutionary” call for action may be heard differently by the PRC women (educated through the writings of Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao) and the local prostitutes who are transitioning between British colonial paternalism and a nascent local democracy under Hong Kong’s Basic Law. The film, however, never broaches the issue of whether the mainland women view Elsie’s political activism differently because of their mainland upbringing. The local feminist lacks any appreciation of the different histories represented by the women in the room. The changes in the PRC’s Marriage Law over the years, the consequences of the one-child policy and the vertiginous transformation in notions of the ideal socialist woman as a worker, peasant or soldier remain alien to her conception of “revolutionary purpose”. While the film implicitly critiques the prudery of feminist condemnation of pornography and sex work, it stops at a libertarian call for respect and a trade-unionist sense of the value of work. Other models of liberation—from radical lesbianism to socialist feminism—remain off the film’s political agenda. A transnational third wave seems about to break, but stops before it can gain momentum.

The camera moves toward Elsie and around the gathering of women during her talk and settles on a medium close-up of her hands in an open gesture, indicating a hope for acceptance. The room erupts in a lively debate about whether the laws against street soliciting should be repealed, whether prostitutes benefit from seeing themselves as “sex workers” or not, and the relative importance of self-respect for the women in the business. Coco speaks up in support of Elsie’s intervention and concludes by saying: “I am criticising all assholes who have deprived us of our right to be whores”. Seeing a general decline in the industry, Jenny laments the days when most of the call girls saved money to further their education. As some of the women challenge Elsie to go into the business herself, calls come in, the bar opens and the women line up for their last night at the club. Elsie remains alone on her soapbox as the other women file out. A clear class divide separates the middle-class activist from the working-class women she hopes to serve. However, the film does provide time on screen for the female intellectual to articulate her position. This recognises her political presence in the territory and gives her feminist message some import and urgency.

Even if her rhetorical delivery seems awkward, the fact that Elsie functions as an educated voice on topics of direct concern to women workers opens up a space for a public dialogue on a range of issues. The film becomes part of a broader feminist conversation on female sexuality, reproduction, women’s legal rights, LGBTQ concerns, heterosexual male privilege, violence against women, global consumerism, and the gendered dimension of the neoliberal marketplace. Like the various local productions of the Vagina Monologues and other female-centred productions, such as Crystal Kwok’s film, The Mistress (迷失森林, 1999), or Barbara Wong’s documentary on some of the same issues, Women’s Private Parts (女人那話兒, 2000). As Wang Lingzhen notes in her Introduction to Chinese Women’s Cinema: Transnational Contexts, the quest for female agency drives the work of many of these filmmakers:

[I]t is in and through a diverse cinematic engagement with historical forces, whether of the market, politics, or patriarchal traditions at national, transnational, or diasporic levels, that Chinese women filmmakers, as historical and authorial subjects, have exhibited their agency, reorienting gender configurations and articulating different meanings and aesthetics in history. (39)

Elsa Chan’s contribution to Whispers and Moans and True Woman for Sale highlights this quest for female agency through her activist characters. Although depicted ambivalently in these films, her female journalists, religious workers, activists and intellectuals play an undeniable role in highlighting aspects of the lives of the women that might otherwise go unnoticed. If other features on prostitution only show women plying their trade rather than advocating for their rights, Whispers and Moans in particular provides a necessary corrective by offering a concrete vision of Hong Kong women taking command of the streets to call for political change with implications for local as well as global feminist causes.

Notes

[1] The reference is, of course, to The World of Suzie Wong (Richard Quine, 1960). For more on this topic, see Peter Feng.

[2] For more on female desire in contemporary China, see Katrien Jacobs.

[3] For a detailed reading of this film, see Wendy Gan.

[4] For more on this film, see Wimal Dissanayake; Pin-chia Feng; and Pheng Cheah.

[5] For more on the global sex trade, see Melissa Gira Grant.

[6] For information on women filmmakers active in the HKSAR, see Gina Marchetti.

[7] Published in Chinese as古老生意新專業: 香港性工作者社會報告 (Old Business New Profession: A Social Report of Hong Kong Sex Workers); the Chinese title of the film (which is in two parts, I and II) is性工作者十日談 (Ten Days of Discussions with Sex Workers).

[8] Elsa Chan’s doctoral thesis is entitled Japanese from China: The Zanryū-Hōjin and Their Lives in Two Countries.

[9] Veg, for example, notes that Whispers and Moans can be read as an allegory of Hong Kong cinema’s relationship to the mainland Chinese market. See Mirana M. Szeto and Yun-Chung Chen for more on the “mainlandization” of Hong Kong’s film industry.

[10] The two-child policy came into effect in 2016.

References

1. “About Us.” Zi Teng. Hong Kong, n.d. Web. 10 June 2015. <http://www.ziteng.org.hk/aboutus/aboutus_e.html>.

2. Aida. Composed by Giuseppe Verdi. 1872. Milan: Ricordi, 1986. Print.

3. All About Love [得閒炒飯]. Dir. Ann Hui. Screenplay by Yang Yeeshan. Class Limited; Mega-Vision Pictures, 2010. Film.

4. Be a Mother [母語]. Dir. Yu Zhong. Beijing Longhai Starlight Media, 2011. Film.

5. Blush [紅粉]. Dir. Li Shaohong. Beijing Film Studio, 1995. Film.

6. Carroll, Alexandra. “Book Upclose: Whispers and Moans”. Hong Kong Magazine 6 Aug. 2011: 26. Print.

7. Chan, Yee-shan. “Japanese from China: The Zanryū-Hōjin and Their Lives in Two Countries.” Diss. U of Hong Kong, 2007. Print.

8. Cheah, Pheng. “Global Dreams and Nightmares: The Underside of Hong Kong as a Global City in Fruit Chan’s Hollywood, Hong Kong.” Hong Kong Culture: Word and Image. Ed. Kam Louie. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2010. 193–221. Print.

9. A Complicated Story [個複雜故事]. Dir. Kiwi Chow. Edko Films; Hong Kong Film Development Fund; Big Star Production, 2014. Film.

10. The Conservancy Association. “Tai Hom Village”. n.d. Internet Archive. Web. 15 Apr. 2012. <https://web.archive.org/web/20120415052524/http://www.conservancy.org.hk/heritage/TaiHom/index_E.htm>.

11. Dissanayake, Wimal. “The Class Imaginary in Fruit Chan’s Films.” Jump Cut 49. Spring (2007). Web. 10 June 2015. <http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc49.2007/FruitChan-class/text.html>.

12. Durian, Durian [榴槤飄飄]. Dir. Fruit Chan. Nicetop Independent Ltd; Studio Canal France, 2000. Film.

13. Ebola Syndrome [伊波拉病毒]. Dir. Herman Yau. Jing’s Production Limited; Orange Sky Golden Harvest Entertainment, 1996. Film.

14. Erens, Patricia Brett. “The Mistress and Female Sexuality.” Hong Kong Screenscapes: From the New Wave to the Digital Frontier. Ed. Esther M.K. Cheung, Gina Marchetti, and See-Kam Tan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2011. 239–52. Print.

15. Fassbinder, Rainer, writ.; dir. Beware of a Holy Whore [Warnung vor einer heiligen Nutte]. Antiteater-X-film; Nova International; Rom, 1971. Film.

16. Feng, Pin-chia. “Reimagining the Femme Fatale: Gender and Nation in Fruit Chan's Hollywood Hong Kong.” Hong Kong Screenscapes: From the New Wave to the Digital Frontier. Ed. Esther M.K. Cheung, Gina Marchetti and See-Kam Tan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2011. 253–62. Print.

17. Feng, Peter X. “Recuperating Suzie Wong: A Fan’s Nancy Kwan-dary.” Countervisions: Asian American Film Criticism. Ed. Darrell Y. Hamamoto and Sandra Liu. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2000. 40–58. Print.

18. Fincher, Leta Hong. Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2014. Print.

19. Finding Mr. Right [北京遇上西雅圖]. Dir. Xue Xiaolu. BDI Films; Beijing H&H Communication Media; Edko Films; Edko (Beijing) Films; China Movie Channel, 2013. Film.

20. Ford, Stacilee. Troubling American Women: Narratives of Gender and Nation in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2011. Print.

21. From the Queen to the Chief Executive [等候董建華發落]. Dir. Herman Yau. Screenplay by Elsa Chan. Nam Yin Production Company Limited, 2001. Film.

22. Gan, Wendy. Fruit Chan’s Durian, Durian. Hong Kong: Hong Kong UP, 2005. Print.

23. The Goddess [神女]. Dir. Wu Yonggang. Lianhua Film Company, 1934. Film.

24. Golden Chicken [金雞]. Dir. Samson Chiu. Panorama Entertainment; Applause Pictures Limited, 2002. Film.

25. Golden Chicken 2 [金雞2]. Dir. Samson Chiu. Applause Pictures, 2003. Film.

26. Grant, Melissa Gira. Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. London: Verso Books, 2014. Print.

27. Guo Xiaolu. A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers. New York: Doubleday, 2007. Print.

28. Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005. Print.

29. Hollywood, Hong Kong [香港有個荷里活]. Dir. Fruit Chan. Nicetop Independent Ltd, 2001. Film.

30. Ho Yuk: Let’s Love Hong Kong [好郁]. Dir. Yau Ching. Made-in-China Productions, 2002. Film.

31. Jacobs, Katrien. People’s Pornography: Sex and Surveillance on the Chinese Internet. Bristol: Intellect, 2012. Print.

32. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Dir. Chantal Akerman. Paradise Films, 1975. Film.

33. Marchetti, Gina, Principal Investigator. Hong Kong Women Filmmakers: Sex, Politics and Cinema Aesthetics, 1997 to the Present. n.d. Web. 5 Feb. 2016. <https://hkwomenfilmmakers.wordpress.com/>.

34. The Mistress [迷失森林]. Dir. Crystal Kwok. Wild Horse Productions Limited, 1999. Film.

35. My Life to Live [Vivre sa vie: film en douze tableaux]. Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. Panthéon Distribution, 1962. Film.

36. The Red Kimona. Dir. Walter Lang, Dorothy Davenport (uncredited). Vital Exchanges, 1924. Film.

37. Rofel, Lisa. Desiring China: Experiments in Neoliberalism, Sexuality, and Public Culture. Durham, N.C.: Duke UP, 2007. Print.

38. The Sandwich Man [兒子的大玩偶]. Dir. Hou Hsiao-Hsien. Central Motion Pictures Corporation, 1983. Film.

39. Sara [雛妓]. Dir. Herman Hau, Emperor Motion Pictures; Rex Film Limited; Fox International Channels; HK Film Production Limited, 2014. Film.

40. She, a Chinese [中國姑娘]. Dir. Guo Xiaolu. UK Film Council; Warp X; Film4, 2009. Film.

41. Sisters and Ziteng [姐姐妹妹與紫藤]. Dir. King-chu Kong. Step Forward Multi Media, 2006. Film.

42. Street Angel [馬路天使]. Dir. Yuan Muzhi. Mingxing Film Company, 1937. Film.

43. Szeto, Mirana M., and Yun-chung Chen. “Mainlandization and Neoliberalism with Post-Colonial and Chinese Characteristics: Challenges for the Hong Kong Film Industry.” Neoliberalism and Global Cinema: Capital, Culture, and Marxist Critique. Ed. Jyostna Kapur and Keith B. Wagner. New York: Routledge, 2011. 239–60. Print.

44. True Women for Sale [性工作者2 我不賣身.我賣子宮]. Dir. Herman Yau. Screenplay by Herman Yau and Yang Yeeshan. Perf. Prudence Liew, Anthony Wong Chau Sang, Race Wong, and Sammy Leung. Mei Ah Entertainment, 2008. DVD.

45. The Untold Story [八仙飯店之人肉叉燒包]. Dir. Herman Yau. Uniden Investments Limited, 1993. Film.

46. Veg, Sebastian. “Hong Kong by Night: Prostitution and Cinema in Herman Yau’s Whispers and Moans.” China Perspectives 2 (2007): 87–88. Print.

47. Wang, Lingzhen. Chinese Women’s Cinema: Transnational Contexts. New York: Columbia UP, 2011. Print.

48. Whispers and Moans [性工作者十日談]. Dir. Herman Yau. Screenplay by Herman Yau and Yang Yeeshan. Mei Ah Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

49. Whiteley, Patrick. “The Era of Prosperity is upon Us.” China Daily. 19 Oct 2007. Web. 11 Feb. 2016. <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2007-10/19/content_6243676.htm>.

50. Women’s Private Parts [女人那話兒]. Dir. Barbara Wong Chun-Chun. Mandarin Films Production Ltd, 2000. Film.

51. Working Girls. Dir. Lizzie Borden. Alternate Current, 1987. Film.

52. The World of Suzie Wong. Dir. Richard Quine. MGM British Studios, 1960. Film.

53. Yang, Yeeshan. Whispers and Moans: Interviews with the Men and Women of Hong Kong’s Sex Industry. Hong Kong: Blacksmith Books, 2006. Print.

54. ---. “Gu lao sheng yi xin zhuan ye : Xianggang xing gong zuo zhe she hui bao gao [Old Business New Profession: A Social Report of Hong Kong Sex Workers].” Tian di tu shu you xian gong si, 2001. Print.

55. Zola, Émile. Nana. 1880. Paris: Fasquelle, 1966. Print.

Acknowledgements

Portions of the research for this article were funded by the General Research Fund, Research Grants Council, Hong Kong, 2011-15 (HKU 750111H).

I am grateful to Iris Eu and Wong Man Man for their help preparing this essay for publication.

Suggested Citation

Marchetti, G. (2015) 'The gendered politics of sex work in Hong Kong cinema: Herman Yau and Elsa Chan (Yeeshan)’s Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 10, pp. 12–30. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.10.01.

Gina Marchetti teaches courses in film, gender and sexuality, critical theory and cultural studies. Her books include Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (University of California, 1993), From Tian’anmen to Times Square: Transnational China and the Chinese Diaspora on Global Screens (Temple University Press, 2006), and The Chinese Diaspora on American Screens: Race, Sex, and Cinema (Temple University Press, 2012). Her current research interests include women filmmakers in the HKSAR, China and world cinema, and contemporary trends in Asian and Asian American film culture.