New Cinema History and the Comparative Mode: Reflections on Comparing Historical Cinema Cultures

Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers

“Thinking without comparison is unthinkable. And, in the absence of comparisons, so is all scientific thought and all scientific research.” (Swanson 145)

One notable direction in the spatial turn within film studies relates to the attention paid to the place where movies were and are actually shown and seen. Over the past fifteen years or so, an impressive number of studies have dealt with the practices, tactics and strategies of screening and consuming movies in picture houses and in other theatrical and nontheatrical environments, including studies on both historical and contemporary experiences. Whereas this type of research is not new and its traces go back to older film sociological and industry-related research traditions (Gripsrud), much of this recent work on moviegoing distances itself from the text-centred focus within film studies, and links up with theories, concepts and methods coming from other fields within the humanities and the social sciences. This movement towards a decentring of the film as the object of study, and towards a multidisciplinary engagement with issues like exhibition and reception, has been labelled “new cinema history” (Maltby, Biltereyst, and Meers; Biltereyst, Maltby, and Meers).

Covering rather different types of research, new cinema history has been prolific in revitalising the field and in revising cinema history, and it has brought forward new types of scholarship (e.g. collaborative, interdisciplinary research teams), innovative research approaches and methodologies (e.g. digital methods, computational tools, geovisualisation) (see Maltby, “New Cinema Histories”; Verhoeven; Aveyard and Moran). Surveying this recent line of cinemagoing studies, this contribution will maintain that the work done so far is largely monocentric in the sense that most studies focus on very specific local practices and experiences, often concentrating on film exhibition and audience experiences in particular cities, neighbourhoods or venues. We will argue that, similarly to what happened in other disciplines, a comparative perspective would be helpful when trying to understand larger trends, factors or conditions explaining differences and similarities in cinema cultures. After a discussion of the (underdeveloped) comparative mode within film studies in general, this contribution will explore some of the challenges of doing comparative research on film exhibition and moviegoing. Concentrating on these issues, different levels of comparison and modes of comparative research will be discussed and illustrated by using data and insights from various historical studies on cinema cultures.

Film Studies and the Comparative Mode

It is a truism that people, whenever observing, evaluating and making concrete judgments and decisions, draw comparisons. The comparative method, Claude Lévi-Strauss argued in his Totemism, “consists precisely in integrating a particular phenomenon into a larger whole” (85). This seems to imply that research that tries to look beyond the confines of the object under investigation is comparative by nature. In this sense, comparison seems to be unavoidable, but also rather vague.

Most disciplines within the humanities and the social sciences, however, have seen a rising demand for a more rigorous and systematic kind of comparison, based on the recognition that the comparative method is an advanced form of observation that allows us to understand the general issue at hand better than if we limit the scope to one geographical or temporal unit only. This kind of comparison entails methodological sophistication and forces researchers to be critical at every stage of their work. Globalisation, postcolonial and world system theories obviously stimulated the development of a comparative mode, but it is safe to say that systematic comparative approaches have been theorised and operationalised more fully within the social sciences than the humanities. Within disciplines like sociology, demography, communication sciences or economics, the practice of comparing societal events, trends and issues across regional, national and other geographical confines is often seen as an integral part of the establishment of research designs, hypothesis testing, and attempts to generate wider conclusions (Grew; Rosser and Rosser; Esser and Hanitzsch; Sasaki et al.). In spite of resistance within the humanities against vigorous forms of comparative research, and especially against their alleged tendency to generalisations and master narratives, the issue has equally come to the forefront in this field as well. Disciplines like literary studies and history have a rich tradition of theorising, institutionalising and doing comparative research. This is most clearly visible within literary studies, where comparative literature is a well-established field, while in history there are strong traditions of long-term social history, histoire croisée or entangled history (Berger; Cohen and O’Connor).

Generally speaking, one might argue that the comparative mode is only weakly developed within film studies. [1] It is true that work on film integrates discussions of particular movies, authors and styles within a larger whole of shifting aesthetic, generic or ideological boundaries, and this could be conceived as comparative following Lévi-Strauss’s definition. It is also a fact that, given the international dimension of the film industry in terms of production, trade and consumption, the comparative mode has always been present in some form or another in film criticism and film studies. Discussions of cultural transfer or of crossnational flows of movies, genres or filmmakers, for instance, always contain some form of comparison, mainly in assessing the relationship between Hollywood and European cinema (e.g. Morrison; Nowell-Smith and Ricci; Trumpbour), or in studies on differences and similarities within a larger region or continent like Europe (Dyer and Vincendeau; Fowler; Biltereyst, Maltby, and Meers; Timoshkina, Harrod, and Liz).

However, in most of these studies the comparison is often implicit rather than explicit (Berger 161), and the question is to what degree this research is analytically comparative in the sense of conceiving and using research designs which enable a thoughtful, systematic comparison of cinematic phenomena across different geographic or temporal entities. Within the wider field of film studies, most of the crossnational comparative work, even the studies dealing with issues linked to social sciences like film policy and industry (e.g. Hjört and Petrie; Biltereyst, Maltby, and Meers), is presented in the form of edited collections of monocentric studies, or parallel descriptions, rather than being truly comparative—at least in the sense of employing more sophisticated approaches with clearly defined (and similar) analytical levels, categories, variables and units of observation.

Besides a reluctance toward methodologies which recall a research ethos akin to the social and natural sciences, part of the explanation for the lack of comparative research relates to cinema’s complexity, which, as Paul Willemen emphasised in his plea for a comparative film studies, should be seen as a thoroughly industrialised cultural form “on the cusp of the economic and the cultural” (99). Willemen argued that, “because of the capital intensive aspects of its production, distribution and exhibition,” cinema is “particularly well suited to provide a way into the question of how socioeconomic dynamics and pressures are translated into discursive constellations” (103). Whereas cinema’s complexity as an economic, societal and cultural institution might be seen to complicate and encumber comparison over time and place, we should acknowledge that much work within film studies is still closely linked to a humanities-oriented view of film as a unique form of art and culture. The masterpiece tradition, as Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery called it in their book on film historiography Film History, is still a vibrant tradition, inspired as it is by literary studies, arts and philosophy, and one which engages with keen attention with particular movies, genres, authors, styles. Within this founding tradition, Allen and Gomery argued, “economic, technological, and cultural aspects of film history are subordinate to the establishment of a canon of enduring cinematic classics” (68). Justifiably, this view of film and cinema often looks at comparative modes of research as obstructing the full appreciation and understanding of the object’s uniqueness in terms of its aesthetic, creative and semiotic meanings. Comparison, if operationalised at all, should respect this complexity and unicity, avoid generalisations, and be careful not to reduce particularising histories to dogmatic or universal principles.

A similar attitude can be observed in other traditions within film studies as well. This is, for instance, the case in work on cinema’s societal meanings in a more ideological-critical vein. [2] Critical work on hegemony and cinema, in particular the one dealing with cinema’s ideological implications, modes of representation and spectatorship, used to be deeply influenced by theories on the cinematic apparatus, and it was heavily criticised for its monolithic and homogeneous view upon cinema (Lapsley and Westlake). Since the early 1990s, however, studies on these issues have tended to look at cinema in terms of its “heterogeneous diversity” (Mayne 78), so that theories on the textually implied spectator shifted in the direction of recognising cinema’s complexity, and reception as being subjected to negotiation, variability and flexibility. Both films and their modes of reception are conceived as temporally and geographically unique as they are characterised by a particular context and by an unprecedented confluence of circumstances.

Also fields of research linked to the new cinema history perspective, such as those dealing with exhibition and cinemagoing, mostly tend to be microhistories on very specific local practices and experiences in one city, neighbourhood or, sometimes, venue. An important part of this work relates to memories of cinemagoing and the remembrance of the particularities of the place and the act of consuming pictures as a complex personal and social experience. Studies in this line of research often take Annette Kuhn’s pioneering ethnohistorical work on cinema memories as a point of departure, and are mostly inspired by Doreen Massey’s view of space, conceived as “the product of interrelations”, as “the sphere of the possibility of the existence of multiplicity,” and as “always under construction” (9). Using oral history accounts, much of this work applies a cultural studies ethos in its attempt to understand cinema as experienced. The spatial dimension is conceptualised here as part of an attempt to capture everyday cultural experiences and the structure of feeling of a local community. Unsurprisingly, this work also concentrates mostly on very particular cases around a geographically defined community, and attempts to capture the experience of the cinema (as a place) and of cinema (as a space encompassing the experience of the movie and of everything around the place) as part of this particular audience’s sense of local belonging (e.g. Jernudd, “Cinema Memory”; Treveri Gennari and Sedgwick; Van de Vijver and Biltereyst). Although these microhistories often integrate their findings into a larger whole, and mostly contain traces of comparison (e.g. Hubbard 261, on differences in the experience of Leicester’s multiplexes, arts cinemas and Bollywood cinemas), scholars hesitate to look beyond these temporal and spatial confines, and to address some overarching tendencies, let alone generalisations. As this perspective very much conceives the place/space of the cinema through its complexity, and through its local embeddedness, only few attempts were made to operationalise a systematically comparative design.

A similar diagnosis on geographical monocentrism can be made for other directions within the new cinema history perspective. This is for instance the case of studies that try to capture audience’s film reception by using sources like cinemagoing statistics and box-office and admission figures (e.g. Harper, on the Regent Cinema in Portsmouth; Jurca and Sedgwick, on Philadelphia), or those relying on programming patterns as an index for audience’s choice and film popularity (e.g. Sedgwick, “Patterns”, on Sydney; Treveri Gennari and Sedgwick, on Rome). Also the growing work on film venues and exhibition structures often focuses upon single case studies, mostly within the confines of one country, region, city or neighbourhood (see examples in Maltby, Biltereyst, and Meers; Biltereyst, Maltby, and Meers).

Figure 1: Home page of the Czeck Film Culture in Brno (1945–1970) project

(www.phil.muni.cz/dedur). Screenshot.

Within the new cinema history perspective, the call for more systematic comparative research has been high on the agenda for some time, and interesting work has been done in this direction on issues of exhibition and programming across city and national borders (e.g. Convents and Dibbets; Sedgwick, Pafort-Overduin, and Boter; Thissen). [3] Currently several comparative projects are being conducted, mainly on film exhibition and programming (e.g. replication studies of the Flemish “Enlightened City” project in Mexico, Colombia, the US, and Spain; comparative research on Belgium and The Netherlands; studies on Ghent, Bari and Leicester) (Lozano et al.). [4] Applying an interdisciplinary ethos and fostering work at the crossroads of humanities and social sciences, an increasing amount of research encompasses more systematic approaches to data collection. Inspired by digital humanities, these studies share a focus on the centrality of collection building and curation, and the will to explore the potential to conduct (big) data driven analysis. Large databases are available now with information on the location of cinemas and on programming, sometimes with oral history accounts, pictures and other archival material; some of them are (partially) made available online (e.g. on Australia, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Italy). [5] In other countries similar kinds of (relatively big) data sets on various aspects of local historical cinema cultures are available and ready to be shared.

Opportunities, Challenges and Pitfalls

The recent proliferation of studies on various aspects of film exhibition and cinemagoing creates an enormous potential for data to be integrated and compared, larger patterns to be discovered, and hypotheses to be tested. It would be possible now, John Sedgwick argues, to “identify and understand cinema-going practices within and across communities, and then territories” (“Patterns” 141). In a similar vein, Richard Maltby claims that “with common data standards and protocols to ensure interoperability, comparative analysis across regional, national and continental boundaries becomes possible”, so that it “contributes to a larger picture and a more complex understanding” of film culture (“New Cinema Histories” 13). Arguing that the comparative mode applies to microhistorical enquiry as well, Maltby, Dylan Walker and Mike Walsh maintain that “whatever their local explanatory aims” microhistories should have the “capacity for comparison, aggregation, and scaling” (98).

In essence, what the comparative method offers is opportunities for dealing with problems of explanation by organising a departure from one given time frame and/or a specific spatial environment, and compare data with trends or phenomena taking place in another time/space context. Besides investigating dis/similar patterns and testing explanatory hypotheses beyond temporal and/or spatial confines (universalising comparison), the comparative mode can also be used in order to discover and specify the uniqueness of phenomena in a particular society (individualising comparison). The case of the huge statistical differences between the Netherlands and Belgium in terms of movie attendance and film exhibition structures offers a fitting example (e.g. Convents and Dibbets; Van Oort; Biltereyst, Meers, and Van Oort), illustrating that comparison forces us to separate out those phenomena which are genuine peculiarities of the locality—phenomena that need to be explained by both cinematic and by noncinematic, hence wider societal conditions. One of the strengths of comparative research is to unravel those explanatory conditions or factors, explaining similarities and differences, but, as French historian Marc Bloch already indicated, this process of disentangling trends and factors might be a hugely complex and nearly interminable process. [6]

The reason for this complexity lies in the fact that, on top of the usual queries in terms of methods and research design, new questions and challenges arise when trying to operationalise comparative historical research on cinema cultures. Besides the issue of the paucity or incompatibility of data available for comparing two or more temporal/spatial entities, there is the problem of the “institutional source” of the data, when organisations or institutions with quite different backgrounds (e.g. newspapers, trade journals or organisations, insurance or police records) are used as sources for historical data. There is also the issue of familiarisation with more than one geographical area and its contexts, when comparing for instance film exhibition tendencies in two or more countries or across different timeframes—a research condition encouraging collaborative research.Comparison also entails specific conceptual and methodological challenges that clearly set them apart from monocultural research. These challenges relate to the function of the conceptual framework, where there needs to be equivalence in terms of concepts and methods. Depending on the explanatory problem that is addressed, hypotheses will have to be defined carefully, cases will have to be selected accordingly, and basic units of comparison will have to be sharply demarcated. In a critical use of the comparative mode, these hypotheses must be clearly defined and theoretically well founded, whereas objects must be equivalent in nature, and similar methods should be used in all stages of data collection, processing and analysis. Within a strictly “orthodox” kind of comparative research, questions arise also on spatial and temporal proximity, stressing the usefulness of the (quasi-) experimental setting where particular conditions (e.g. same language, similar size, neighbouring regions or countries) are stabilised as much as possible. It refers to the question, for instance, whether comparing Belgium’s historical cinema culture with the Dutch one is more valid than comparing it with Latin American ones. As we will argue, the latter comparison is quite as valid.

A key question, of course, is what exactly will be compared and how. When designing comparative research, concrete decisions will have to be made on issues of the delimitation of space (a country, a region or a county, a city, a neighbourhood, a venue, part of a venue, …) and time (a year, a month, a day, an evening, a single screening, …). Comparative work, like the one we are doing with scholars in Mexico (Lozano et al.), where a quasi-identical research design to the one we applied in Flanders is used (Meers, Biltereyst, and Van de Vijver; Biltereyst, Meers, and Van de Vijver), is quite confronting in interrogating some of these seemingly obvious temporal and spatial dimensions. In a Western European context, a film venue mostly is a fixed building with bricks, stones and a roof—while mobile cinemas became rather quickly a marginal phenomenon—and film programmes are announced in mainstream newspapers. In a city like Monterrey, Mexico, night-time mobile and open air screenings, like those referred to as terrazas, were a widely developed phenomenon, underlining the importance of often overlooked conditions like weather or climate, next to issues of class as the terraza cinema experience was mostly reserved to lower-class audiences. These various conditions in terms of class, climatological, material and spatial dimensions not only emphasise the fluidity of the cinema concept, they also heavily influence the availability and use of sources and research conditions. In the case of Monterrey, terraza screenings for lower social classes were mostly not listed in newspapers or trade journals, and could only be discovered via oral histories. Another unexpected complication of the comparative set-up was that in Monterrey, movies reappeared under different titles, probably for programming tactics or for reasons connected with protecting (or usurping) exploitation rights. It took some time before we realised that these different circumstances in how movies were scheduled, announced and screened had an impact on the first set of data we had gathered on issues like the number of film venues and seats, or on the amount of film screenings and films on the local market. It was only after a thorough understanding of the distinct cinematic and non-cinema-related context in Monterrey and the Flemish cities of Ghent and Antwerp, and after applying a triangulation of methods (inventory of places, analysis of the exhibition market, oral history, programming analysis), that we were able to start comparing and analysing particular aspects of historical cinema cultures. [7]

So, comparative work on these matters needs to tackle questions on the definition of the object and units of observation, as well as on the categories and variables to be used while collecting and analysing data (Grew; Berger). Overseeing the research under the new cinema history umbrella, one can only come to the conclusion that a great variety of qualitative and quantitative methods are employed, very different time and spatial frames used, and that comparison will have to confront problems concerning organisation, standardisation and verification of data. Some lines of research like qualitative microhistories of cinema memories and everyday life experiences will be more difficult to operationalise in terms of meaningful comparison, especially because principles of comparison like selection, abstraction and a rigorous definition of units, categories or variables are often perceived as diametrically opposed to writing the history of highly contextualised practices and meanings. While working with dissecting stories coming out of the raw material of the accounts (Häberlen), comparative work on cinema memories will have to come to a research design with clear decisions on how to collect, process and analyse these stories (e.g. decisions on the interview protocol, on the basic analytical unit, categories and variables). On the other hand, this design will have to be sufficiently open to local peculiarities in order to create an interpretative space for differences and analogies.

Figure 2: HoMER Projects website (homernetwork.org/dhp-projects/homer-projects-2). Screenshot.

Although research using quantitative data could be considered as more apt to comparison because of the availability of numerical data and statistical software, quite similar methodological pitfalls and challenges in terms of interoperability and incompatibility occur. In an ideal scenario with lots of quantitative data on issues like the number of cinemas, seats or box-office revenues, clear decisions are to be made at different stages of the research here as well (cf. defining hypotheses, conceptual framework, time/spatial frames, selection of objects, units, categories and variables). In reality, however, such a rigorous and demanding, “truly” comparative methodological framework will be hard to operationalise within historical research, and other more creative approaches will have to be applied. One approach is the close collaboration between researchers on those topics, and the development of common standards across the projects. Another is the development of online databases, as is the case within the HoMER environment, or the use of software which enables researchers to cross-search those data sets, along with digital tools that can share and contextualise it all (Klenotic). [8]

Comparative Modes, Dis/similar Patterns and Conditions

Looking at the recent rise of historical work on screening, programming and consuming moving pictures, it is clear that most studies focus upon quite different time frames and spatial entities, and that diverse research designs and methods are employed. Although this methodological heterogeneity does not offer an ideal platform for comparison, we would like to argue that even those studies that were not conceived to be integrated into a comparative set-up (can) provide interesting insights for understanding dis/similarities in cinema cultures, as much as they might be helpful in recognising particular recurrent patterns and conditions influencing them. In other words, the “truly” orthodox comparative design with its rigorous methodological set-up doesn’t necessarily have a monopoly on the comparative sensibility, or on how to investigate dis/similar patterns and the conditions underneath them.

In what follows we suggest four types or modes of comparison (Table 1). These modes or sensibilities of comparison refer to bringing together studies that differ in terms of the variety of methodologies used on the one hand, and in relation to the amount and types of spatial or temporal entities examined on the other hand. Concentrating on the geographical dimension, we make a distinction between modes that use studies or data sets with similar and dissimilar methods on one or more geographical sites. In this schematic overview the first mode of comparison evidently is the most unstructured one, whereas the other ones go deeper in exploring dis/similar patterns in historical cinema culture and cinemagoing experiences as they focus on a single place or apply a similar methodological set-up. These comparative modes or sensibilities are also different in how they are open to explore, examine or confirm hypotheses which are based on previous comparisons. Whereas the first mode on multiple method and multiple sites can only be useful for a first overarching look, the other modes can be used for exploring and confirming hypotheses.

Mode 1

multiple places/spaces/sites

//

multiple methodological framesMode 2

single place/space/site

//

multiple methodological frames

Mode 3

multiple places/spaces/sites

//

similar methodological frame

Mode 4

single place/space/site

//

similar methodological frameTable 1: Modes of comparative research (spatial dimension).

Looking at the first, multimethod/multiple site mode, it is clear that this constitutes a quite amorphous comparative approach. It refers to the large majority of research that, even if it uses other research designs, can be useful in order to get a grip on some wider trends, conditions and hypotheses. Obviously, when operationalising this comparative mode, studies need to be brought together that use data and sources on equivalent levels of methodology, space and time. This means, for instance, that audiences’ historical cinemagoing experiences examined through oral histories will produce quite different insights than employing surveys. Another issue relates to the particularity of the places/spaces examined, with work done so far on different geographical realities like particular regions (Aveyard, on rural Australia; Jernudd, “Cinema, Memory”, on the region of Bergslagen; Stead, on Yorkshire), cities (Jernudd, “Cinema, Memory”, on Fagersta; Treveri Gennari and Sedgwick, on Rome; Van de Vijver and Biltereyst, on Ghent), or venues (McIver, on Liverpool’s Rialto).

Although this comparative mode is not very useful for testing hypotheses, it can be inspirational for identifying and recognising patterns and conditions. Considering results from other regions or cities inspires researchers to look differently at their own material and findings and to evaluate the importance of particular conditions more attentively. One example is the issue of tourism and its importance for local cinema culture, as exemplified in the work done in the UK by Tim Snelson. His analysis of three seaside cinemas along the “Golden Mile” in Great Yarmouth in the years 1954, 1964 and 1974 inspired us to look more closely to data gathered in Flanders, more in particular on the coastal tourist city of Ostend (see also Geuvens and Benoit). Although different methodologies were used in both regions, we acknowledged quite similar patterns in the Belgian case as with Snelson’s findings about tourism and its influence on cyclical seasonal changes in cinema attendance, along with the importance of the massive influx of working-class audiences for shifts in cinema’s programming. Of course, tourism is only one of the many conditions having an impact on how, when and where movies were exhibited and consumed. The example illustrates how non-cinema-related factors like the importance of weather, class and economic conditions are interrelated with cinematic issues.

A second, more advanced form of comparison relates to a set-up where studies are brought together and, although using different methodological frameworks, focus on one (more or less) consistent geographical unit. Multimethod/single-site comparison is an individualising type of comparison because it attempts to discover the cinematic and noncinematic factors which condition cinemagoing and cinema culture in a particular society. One direction in this comparative mode relates to methodological triangulation, where different methodologies are employed within one design. Within new cinema history, triangulation is well established in historical audience research, where oral histories are often combined with surveys or other types of sources (Biltereyst, Lotze, and Meers). Another direction tries to produce an overview of, and bring together, studies that, although using other designs, focus on the same city, region, country or other geographical unit.

An interesting example here is the cinema-historiographical work on the Netherlands, especially the one done in the slipstream of the groundbreaking Cinema Context research project (Dibbets) (Figure 3). In the past few decades, scholars in the Netherlands concentrated on the question why film attendance had been so low there, at least compared to other European countries, and why the film exhibition market was relatively undersized in terms of the number of film venues or seats. Although different methods were used (and, at times, other geographical boundaries set), a fertile line of research and scholarly debate emerged on the case of the particularities of the historical Dutch cinema culture. Although some of this work operationalised a comparison with other countries like Belgium (e.g. Convents and Dibbets) or the UK (Sedgwick, Pafort-Overduin, and Boter), Dutch film historians had a very fertile discussion on trends, factors and conditions explaining the particularities of their national cinema history (e.g. Dibbets, “Het taboe”; Pafort-Overduin, Sedgwick, and Boter; Thissen; Van Oort). The dialogic nature of Dutch historical cinema studies is interesting, not only for understanding what happened in the Netherlands. It also underlines how both cinematic and non-cinema-related conditions were important in order to grasp the larger dynamics within the Dutch film culture. Among the noncinematic conditions we find arguments on the influence of Calvinism and its view upon visual culture and cinema, the vertical stratification of Dutch society, or class, explaining how cinema had difficulties to attract middle- and upper-class audiences. Besides this mixture of religious, ideological and other societal conditions, issues related to the film industry itself were examined. Hypotheses were raised as to the impact of the severe national censorship system, heavy municipal entertainment taxes, and to the policy of the Dutch film exhibitors’ association to restrict the number of cinema operations in the country (Sedgwick et al.; Thissen; Van Oort).

Figure 3. Opening web page of the Dutch Cinema Context project (www.cinemacontext.nl). Screenshot.

The third mode entails a more sophisticated kind of comparison, one where aspects of cinema culture are examined at different places by using an identical methodological set-up. In an ideal scenario here, researchers working on cinema history at different places collaborate and agree on using a symmetrical methodological set-up. Although this kind of collaboration is still quite rare within the humanities, it enables a more detailed and reliable examination and comparison of data, patterns and conditions. It also encourages researchers to examine more closely the different levels at which national, regional or urban cinema cultures are to be compared. The above-mentioned crossnational research that we are conducting with Mexican and other teams in Spain, Columbia and the US is based on prior comparative work we carried out in Belgium, more precisely on cinema’s history in Flemish cities (Biltereyst, Meers, and Van de Vijver; Biltereyst, Lotze, and Meers; Meers, Biltereyst, and Van de Vijver). [9] For this comparative study, teams in Ghent and Antwerp operationalised a triangulation of approaches, consisting of building longitudinal databases on film exhibition structures (mainly on venues and places) and film programming (a sample of weeks and years), supplemented by the use of oral history accounts.

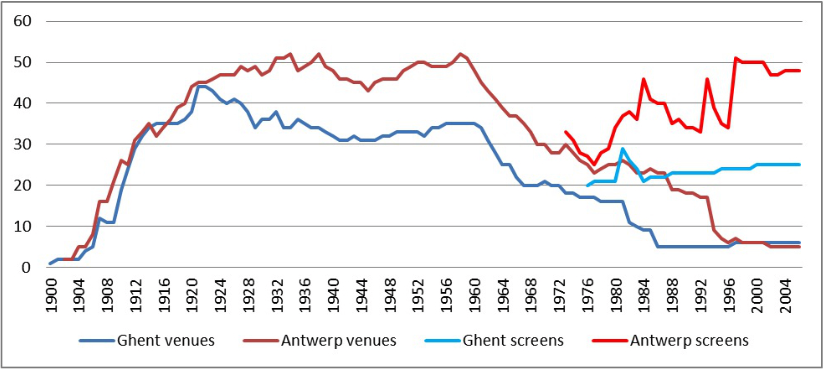

Instead of presenting results from this integrated cross-urban study, we prefer here to reflect upon its potential for comparison. One of the first steps in the comparative analysis was to look at the historical shifts in the number of cinemas and screens (Figure 4). At first sight we observed a quite similar pattern in relation to the historical growth, stabilisation and decline of cinema, along with the emergence of the multiscreen and multiplex phenomenon, mainly from the 1970s onwards. Obviously, we needed to take into account population size, showing that, whereas Ghent was a much smaller city in terms of the number of inhabitants, [10] it had relatively more cinemas, but also much smaller ones with lower averages in the number of seats.

Figure 4: Number of film venues and screens in Antwerp and Ghent (1900–2006).

This first comparative step forced us to even look beyond sociodemographic characteristics and include issues of the structure and political economy behind the local film exhibition scene. We needed to look at the different internal dynamics, where for instance the degree of concentration of cinemas was (at least for a large part of its history) more explicit in Antwerp than in Ghent (Lotze and Meers). We had to put it all into a wider geographical perspective, concentrating here on both cities’ larger socioeconomic and geographic functions within the city region. Inspired by Walter Christaller’s central place theory, we could argue that both cities played a key role in the Flemish spatial structure; Ghent and Antwerp occupied a central place in their respective city regions, mainly by providing goods and services like entertainment beyond the city borders (Biltereyst and Van de Vijver). One of the differences here was that Antwerp was not only a bigger city, but also that its city region was more extended than the one around Ghent.

Another level of this multilayered comparison between the historical cinema cultures in the two Flemish cities relates to the different dynamics in terms of the flow of films, language and programming strategies within the cities (on Ghent, see Van de Vijver and Biltereyst). Ghent seems to have had a much more centrifugal structure around a few film centres, whereas the main shopping street for long remained the heart of Antwerp’s more centripetal exhibition scene. Another dimension relates to the different film circuits and their strategies within a city. One example here is that, at least in the last few decades, Ghent had a more vivid arthouse circuit, which we related to the condition that Ghent had a larger university student population than Antwerp.

This example of a collaborative, cross-urban and methodological symmetrical research set-up illustrates the different levels of comparison when studying historic cinema cultures. Based on our experience, we think that an analysis of how the film exhibition scene of the two or more geographical units differed and evolved in terms of number of venues, screens, seats, films and screenings, should first of all be framed within a close comparative examination of the structure, control and the internal dynamics within a market. This includes taking into account sociodemographic and economic issues like population and class differences, along with putting the data into the frame of the sociogeographic structure of the respective cities (e.g. class linked to neighbourhoods). To take this further, we think, it is necessary for this intra-city analysis to be complemented by extra-city levels of comparison. This relates to a more distant look at the urban film scene within a wider socioeconomic and geographic context, including mobility, transport, leisure and other issues related to urban functions within the reach of city regions and other geographic contours (e.g. entertainment, shopping, education).

A few words, finally, on the hypothetical fourth mode of comparative work on historical cinema cultures. At first glance, this mode of bringing together studies which use a similar method and focus upon the same space/place/site, seems quite unusual, probably even useless. However, in many disciplines the practice of replication studies is seen as one of the main principles of scientific method, or as a standard procedure to gain more and a better insight into the robustness and reliability of earlier findings. Replication, duplication or reproducibility are not part of the humanities or film studies vocabulary, for sure, and they even have the aura of wiping out the researcher’s creativity and originality. However, this shouldn’t be the case. Consider oral history work on cinemagoing, where bias of subjectivity arises at every level of collecting, processing, analysing and interpreting accounts. Also in other fields within new cinema history, interpretation and subjective evaluation are important, making replication an interesting strategy to explore, mainly in an attempt to test hypotheses or to explore new dimensions.

Discussion

This article looked at the recent growth of studies on historical film exhibition and cinemagoing experiences as an unprecedented opportunity to better understand the differences and analogies in how films were shown and received in the past. In order to come to a more refined view of larger trends and their underlying conditions, we maintained that, similarly to what happened in many other fields of research, comparison needs to be developed in more sustained manners. Comparison, we might argue, is an essential part of a discipline’s strategy to become methodologically more mature, to stimulate a dialogic debate, and to establish a better understanding of the object under study. Within film and cinema studies, the rise of the new cinema history perspective went hand in hand with an urge for data collection and curation, and offers an enormous potential for comparison at many levels.

This partly self-reflective contribution aimed to specify the various options for developing the comparative sensibility within cinema studies. Comparison can be a built-in option within one research set-up, but the accumulation of studies offers much wider opportunities which go further than the rigorous application of (what we called) the orthodox or “truly” comparative design. Four distinct modes of comparison were discussed, and we showed how these different types were distinct in terms of being inspirational, exploring or testing hypotheses on dis/similar trends and conditions. We referred to individualising (modes 2 and 4) and universalising (modes 1 and 3) types of comparison, whereas principles, levels, pitfalls and other aspects of comparative good practices were discussed (equivalence, proximity, familiarity, verification).

A key outcome of enhancing the comparative sensibility within new cinema history should be the refinement of the idea that going to the movies was more than watching them and that it was a complex social experience. Comparison should take into consideration how and where precisely particular patterns occur(ed), and which conditions must be taken into account in order to put these into perspective. The examples showed that these conditions ranged from cinema-related factors like the power structure in the film market, to wider societal, demographic, geographic, economic or even climatological circumstances—often arising in an intertwined manner like in the case of tourism. Refining and contextualising these trends and conditions should be part of the exercise to take some distance from, and put into perspective, findings of particular microhistorical studies.

We hope to have indicated that comparison is more than the orthodox version of it, and that the comparative mode or sensibility should cultivate the idea that we need to look at cinema both from a close and a distant perspective. The outcome shouldn’t be to come to absolute generalisations or any kind of strict laws conditioning cinemagoing. The comparative sensibility, on the contrary, is best seen as a dialectic perspective because it should maintain that the cinema experience is best understood as both socially situated and as a particularising, complex and unique practice. “The most effective comparative histories,” Peter Baldwin argued, are those “which, eschewing generalizations, formulate arguments at a middle range about differences and similarities” (11). Finally, what the comparative mode should also make clear is that much of what cinema has been remains unexplored, with much work still to be done in and outside the regions covered so far.

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank Kathleen Lotze, José Carlos Lozano and Lies Van de Vijver.

Notes

[1] Comparative film studies as a perspective can also take another stance, for instance in the way Paul Willemen referred to it, namely as a discipline which tries to break an Anglophone UK/US-centred hegemony of the discipline.

[2] Some of this work uses methodologies of textual interpretation in order to illuminate how particular films, styles or genres are to be interpreted symptomatically for understanding wider ideological, political and social trends (see criticism by Maltby, “How Can Cinema History”).

[3] The issue of comparative research is also a key focus at the HoMER@NECS Conference in Potsdam, Germany, 27–30 July 2016 (http://necs.org/conference/homer/).

[4] See also current work done by researchers at Oxford Brookes University, De Montfort University and Ghent University.

[5] See the Czeck Film Culture in Brno (1945–1970) project (www.phil.muni.cz/dedur), the Dutch Cinema in Context database (www.cinemacontext.nl), the German Siegen project (www.fk615.uni-siegen.de/earlycinema/index_en.htm), the London Project (londonfilm.bbk. ac.uk), and the Italian cinema audiences project (italiancinemaaudiences.org).

[6] See his well-known quote that “the good historian is like the giant of the fairy tale. He knows that wherever he catches the scent of human flesh, there his quarry lies” (Bloch 26).

[7] Although there are obvious differences in terms of cultural, demographic, political-economic and geographic characteristics (e.g. distance to the USA, language), Antwerp and Ghent share some common traits with Monterrey. None of these cities are capitals of their countries, but they all play an important role in their regions, as attraction poles for industry, entertainment etc. All three have developed some kind of modern urban culture, with cinema as a partner in these modernisation processes. Furthermore, the cities, as part of national film markets very open to US films, experienced the impact of US dominance in the international film flows, each to its degree on the local level.

[8] HoMER (History of Moviegoing, Exhibition and Reception) is an international network of researchers interested in understanding the complex phenomena of cinemagoing, exhibition, and reception from a multidisciplinary perspective. The HoMER website gives an overview of projects using oral histories, mapping or datasets, and combinations of those methodologies (homernetwork.org/dhp-projects/homer-projects-2).

[9] There were three projects: the joint University of Antwerp and Ghent University research project “The Enlightened City”: Screen Culture between Ideology, Economics and Experience (Scientific Research Fund Flanders/FWO-Vlaanderen, 2005–2008); Gent Kinemastad. A Multimethodological Research Project on the History of Film Exhibition, Programming and Cinemagoing in Ghent and its Suburbs (1896–2010) as a Case within a Comparative New Cinema History Perspective (Ghent U Research Council BOF, 2009–2012); and Antwerpen Kinemastad. A Media Historic Research on the Post-War Development of Film Exhibition and Reception in Antwerp (1945–2010) with a Special Focus on the Rex Concern (Antwerp U Research Council BOF, 2009–2011).

[10] In 1952, for instance, Ghent counted 164.700 inhabitants, Antwerp 261.400.

References

1. Allen, Robert C., and Douglas Gomery. Film History: Theory and Practice. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1985. Print.

2. Aveyard, Karina. “The Place of Cinema and Film in Contemporary Rural Australia.” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 8.2 (2011): 294–307. Web. 21 June 2016. <http://www.participations.org/Volume%208/Issue%202/3a%20 Aveyard.pdf>.

3. Aveyard, Karina, and Albert Moran, eds. Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect Books / U of Chicago P, 2013. Print.

4. Baldwin, Peter. “Comparing and Generalizing.” Comparison and History: Europe in Cross-National Perspective. Eds. Deborah Cohen and Maura O’Connor. New York: Routledge, 2004. 1–22. Print.

5. Berger, Stefan. “Comparative History.” Writing History: Theory and Practice. Eds. Stefan Berger, Heiko Feldner, and Kevin Passmore. London: Hodder Arnold, 2003. 161–79. Print.

6. Biltereyst, Daniel, and Lies Van de Vijver. “Cinema in the ‘Fog City’. Film Exhibition and Geography in Flanders.” Cinema Beyond the City: Filmgoing in Small-Towns and Rural Europe. Eds. Judith Thissen and Clemens Zimmerman. London: British Film Institute, 2017. Print.

7. Biltereyst, Daniel, Kathleen Lotze, and Philippe Meers. “Triangulation in Historical Audience Research: Reflections and Experiences from a Multi-methodological Research Project on Cinema Audiences in Flanders.” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies 9.2 (2012): 690–715. Web. 21 June 2016. <http://www.participations.org/Volume%209/Issue%202/37%20Biltereyst_Lotze_Meers.pd>.

8. Biltereyst, Daniel, Philippe Meers, and Lies Van de Vijver. “Social Class, Experiences of Distinction and Cinema in Postwar Ghent.” Explorations in New Cinema Histories: Approaches and Case Studies. Eds. Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, 2011. 101–24. Print.

9. Biltereyst, Daniel, Philippe Meers, and Thunnis Van Oort. “Cinema and Comparative History”. Routledge Companion to New Cinema History. Eds. Daniel Biltereyst, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers. London: Routledge, 2017. Print.

10. Biltereyst, Daniel, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers, eds. Cinema, Audiences and Modernity. London: Routledge, 2012. Print.

11. Bloch, Marc. The Historian’s Craft [1954]. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004. Print.

12. Christaller, Walter. Central Places in Southern Germany. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1966. Print.

13. Cohen, Deborah, and Maura O’Connor, eds. Comparison and History: Europe in Cross-National Perspective. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

14. Convents, Guido, and Karel Dibbets. “Verschiedene Welten. Kinokultur in Brüssel und in Amsterdam 1905–1930.” Kinoöffentlichkeit/Cinema’s Public Sphere (1895–1920). Eds. Corinna Müller and Harro Segeberg. Marburg: Schüren Verlag, 2008. Print.

15. Dibbets, Karel. “Het taboe van de Nederlandse filmcultuur: Neutraal in een verzuild land.” Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 9.2 (2006): 46–64. Print.

16. Dyer, Richard, and Ginette Vincendeau, eds. Popular European Cinema. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

17. Esser, Frank, and Thomas Hanitzsch, eds. The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research. London: Routledge, 2012. Print.

18. Fowler, Catherine, ed. The European Cinema Reader. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

19. Geuvens, Johan, and Régis Benoit. De Wonderlijke Wereld van Pluche en Pellicule: De Geschiedenis van de Oostendse Cinema’s. Oostende: Lowyck, 2010. Print.

20. Grew, Raymond. “The Case of Comparing Histories.” The American Historical Review 85.4 (1980): 763–78. Print.

21. Gripsrud, Jostein. “Film Audiences.” The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Eds. Jill Hill and Pamela Church Gibson. Oxford: Oxford UP: 202–11, 1998. Print.

22. Häberlen, Joachim C. “Reflections on Comparative Everyday History.” The International History Review 33.4 (2011): 687–704. Print.

23. Harper, Sue. “Fragmentation and Crisis.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 26.3 (2006): 361–94. Print.

24. Hjört, Mette, and Duncan Petrie, eds. The Cinema of Small Nations. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2007. Print.

25. Hubbard, Phil. “A Good Night Out? Multiplex Cinemas as Sites of Embodied Leisure.” Leisure Studies 22 (2003): 255–72. Print.

26. Jernudd, Asa. “Cinema Memory: National Identity as Expressed by Swedish Elders in an Oral History Project.” Northern Lights 11 (2013): 109–22. Print.

27. ---. “Cinema, Memory, and Place-related Identities.” Regional Aesthetics. Eds. Erik Healing, Olof Hedling, and Mats Jönsson. Stockholm: National Library of Sweden, 2010: 169–89. Print.

28. Jurca, Catharine, and John Sedgwick. “The Film’s the Thing: Moviegoing in Philadelphia, 1935–36.” Film History 26.4 (2014): 58–83. Print.

29. Klenotic, Jeffrey. “Connecting the Dots: Renewing the Quest for a Scalable, Open-Ended, Cross-Searchable GIS Database for a Global HoMER Project.” University of Potsdam, NECS/HoMER Conference. 28–30 July 2016. Conference paper.

30. Kuhn, Annette. “Heterotopia, Heterochronia: Place and Time in Cinema Memory.” Screen 45.2 (2004): 106–14. Print.

31. ---. An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002. Print.

32. Lapsley, Robert, and Michael Westlake. Film Theory: An Introduction [1988]. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2006. Print.

33. Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Totemism [1963]. London: Merlin Press, 1991. Print.

34. Lotze, Kathleen, and Philippe Meers. “ Citizen Heylen.” Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 13 (2010): 80–107. Print.

35. Lozano, José Carlos, Daniel Biltereyst, Lorena Frankenberg, Philippe Meers, and Lucila Hinolosa. “Exhibición y programación cinematográfica en Monterrey, México de 1922 a 1962: un estudio de caso desde la perspectiva de la ‘Nueva historia del cine’.” Global Media Journal 9.18 (2012): 73–94. Web. 21 June 2016. <https://journals.tdl. org/gmjei/index.php/GMJ_EI/article/view/37>.

36. Maltby, Richard. “How Can Cinema History Matter More?” Screening the Past 22 (2007). Web. 21 June 2016 <http://tlweb.latrobe.edu.au/humanities/screeningthepast/22/ board-richard-maltby.html>.

37. ---. “New Cinema Histories.” Explorations in New Cinema Histories: Approaches and Case Studies. Eds. Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, 2011. 3–40. Print.

38. Maltby, Richard, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers, eds. Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Print.

39. Maltby, Richard, Dylan Walker, and Mike Walsh. “Digital Methods in New Cinema History.” Advancing Digital Humanities: Research, Methods, Theories. Eds. Paul Arthur and Katherine Bode. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. 95–112. Print.

40. Massey, Doreen. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1994. Print.

41. Mayne, Judith. Cinema and Spectatorship. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

McIver, Glen. “Liverpool’s Rialto: Remembering the Romance.” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies 6.2 (2009): 199–218. Web. 21 June 2016. <http:// www.participations.org/Volume%206/Issue%202/mciver.pdf>.42. Meers, Philippe, Daniel Biltereyst, and Liesbet Van de Vijver. “Metropolitan vs Rural Cinemagoing in Flanders, 1925–1975.” Screen 51.3 (2010): 272–80. Print.

43. Morrison, James. Passport to Hollywood: Hollywood Films, European Directors. Albany, NY: State U of New York P, 1998. Print.

44. Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, and Steven Ricci. Hollywood and Europe: Economics, Culture, National Identity, 1945–95. London: BFI, 1998. Print.

45. Pafort-Overduin, Clara, John Sedgwick, and Jaap Boter. “Drie mogelijke verklaringen voor de stagnerende ontwikkeling van het Nederlandse bioscoopbedrijf in de jaren dertig.” Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 13.2 (2010): 37–59. Print.

46. Rosser, J. Barkley, and Marina Rosser. Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy. 2nd ed. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2004. Print.

47. Sasaki, Masamichi, Jack Goldstone, Ekkart Zimmermann, and Stephen K Sanderson. Concise Encyclopedia of Comparative Sociology. Boston: Brill, 2014. Print

48. Sedgwick, John. Popular Filmgoing in 1930s Britain. A Choice of Pleasures. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2000. Print.

49. ---. “Patterns in First-Run and Suburban Filmgoing in Sydney in the mid-1930s.” Explorations in New Cinema Histories: Approaches and Case Studies. Eds. Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, 140–58, 2011. Print.

50. Sedgwick, John, Clara Pafort-Overduin, and Jaap Boter. “Explanations for the Restrained Development of the Dutch Cinema Market in the 1930s.” Enterprise and Society 13.3 (2012): 634–71. Print.

51. Snelson, Tim. “Where the Exceptional and the Everyday Meet: Post-War Cinema Culture in British Seaside Towns.” Cinema Beyond the City: Filmgoing in Small-Towns and Rural Europe. Eds. Judith Thissen and Clemens Zimmerman. London: British Film Institute, 2017. Print.

52. Stead, Lisa. “‘The Big Romance’: Winifred Holtby and the Fictionalisation of Women’s Cinemagoing in Interwar Yorkshire.” Women’s History Review 22.5 (2013): 759–76. Print.

53. Swanson, Guy E. “Frameworks for Comparative Research: Structural Anthropology and the Theory of Action.” Comparative Methods in Sociology: Essays on Trends and Applications [1971]. Ed. Ivan Vallier. Berkeley: U of California P, 1973: 141–202. Print.

54. Thissen, Judith. “Understanding Dutch Film Culture: A Comparative Approach.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 6 (Winter 2013). Web. 21 June 2016. <https://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue6/HTML/ArticleThissen.html>.

55. Thissen, Judith, and André van der Velden. “Klasse als factor in de Nederlandse filmgeschiedenis. Een eerste verkenning.” Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis 12.1 (2009): 50–72. Print.

56. Timoshkina, Alissa, Mary Harrod, and Mariana Liz. The Europeanness of European Cinema: Identity, Meaning, Globalisation. London: I.B. Tauris, 2015. Print.

57. Treveri Gennari, Daniela, and John Sedgwick. “Memories in Context: The Social and Economic Function of Cinema in 1950s Rome.” Film History 27.2 (2015): 76–104. Print.

58. Trumpbour, John. Selling Hollywood to the World: U. S. and European Struggles for Mastery of the Global Film Industry, 1920–1950. New York: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

59. Van de Vijver, Lies, and Daniel Biltereyst. “Cinemagoing as a Conditional Part of Everyday Life: Memories of Cinemagoing in Ghent from the 1930s to the 1970s.” Cultural Studies 27.4 (2013): 561–84. Print.

60. Van de Vijver, Lies, Daniel Biltereyst, and Khaël Velders. “Crisis at the Capitole: A Cultural Economics Analysis of a Major First-run Cinema in Ghent, 1953–1971.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 35.1 (2015): 75–124. Print.

61. Van Oort, Thunnis. “Industrial Organization of Film Exhibitors in the Low Countries: Comparing the Netherlands and Belgium, 1945–1960.” Historical Journal of Film,

Radio and Television. 17 March 2016. Web. DOI:10.1080/01439685.2016.1157294.62. Verhoeven, Deb. “New Cinema History and The Computational Turn.” Beyond Art, Beyond Humanities, Beyond Technology: A New Creativity. Proceedings of the World Congress of Communication and the Arts Conference, University of Minho, 2012. Print.

63. Willemen, Paul. “For a Comparative Film Studies.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6 (2005): 98–112. Print.

Suggested Citation

Biltereyst, Daniel, and Philippe Meers. “New Cinema History and the Comparative Mode: Reflections on Comparing Historical Cinema Cultures.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 11 (Summer 2016): 13–32. https://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue11/HTML/ArticleBiltereystandMeers.html. ISSN: 2009-4078.

Daniel Biltereyst is Professor in film and media studies at the Department of Communication Studies (Ghent University), where he leads the Centre for Cinema and Media Studies (CIMS) and the DICIS network (Digital Cinema Studies). He has published extensively on film/cinema history, and on media censorship and reception. Recently he published Explorations in New Cinema History (2011), Cinema, Audiences and Modernity (2012, both with R. Maltby and Ph. Meers), Silencing Cinema (2013, with R. Vande Winkel) and Moralizing Cinema (2015, with D. Treveri Gennari). He is now working on the Routledge Companion to New Cinema History (2017, with R. Maltby and Ph. Meers) and a themed issue for Memory Studies (2017, with A. Kuhn and Ph. Meers).

Philippe Meers is Professor in film and media studies at the University of Antwerp (Belgium), where he chairs the Center for Mexican Studies and is deputy-director of the Visual and Digital Cultures research center (ViDi). He has published widely on historical and contemporary film culture and audiences (e.g. in Screen, and in Participations). With R. Maltby and D. Biltereyst, he edited Explorations in New Cinema History (2011) and Cinema, Audiences and Modernity (2012), and is editing The Routledge Companion to New Cinema History (2017). With Annette Kuhn and Daniel Biltereyst he is guest editor for a theme issue of Memory Studies (2017).