Representing Ethnicity in Cinema during Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative: A Critical Analysis of My Marlon and Brando (Karabey, 2008), The Storm (Öz, 2008) and Future Lasts Forever (Alper, 2011)

Zeynep Koçer and Mustafa Orhan Göztepe

In 2009, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) launched Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative, a series of social, political and economic reforms addressing the improvement of citizenship rights for Turkish citizens of Kurdish origin. [1] Social debates on ethnic minorities in general and Kurdish minorities in particular have always been present in Turkey. However, the Initiative furthered these debates by making the already present political actors more visible and by creating new ones in the public sphere, which resulted in a major flux in cultural products that highlighted the need to bring forth the Kurdish question. This article analyses the films My Marlon and Brando (Gitmek: Benim Marlon ve Brandom, HüseyinKarabey, 2008), The Storm (Bahoz, KazımÖz, 2008) and Future Lasts Forever (Gelecek Uzun Sürer, Özcan Alper, 2011). It aims to discuss different representations of Kurdishness in cinema in Turkey within the socio-political context of the 2000s—a decade socially, culturally and politically influenced by the Initiative.

Minorities in Turkey have been a central topic in Turkish politics since the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923 as it inherited the population of the Ottoman Empire, which was both ethnically and linguistically diverse. With the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founding elite started a series of political and social reforms to terminate the socio-political and judicial authority of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. [2] To achieve these goals, the new government used the West as a model and nationalism as a tool for nation building; [3] this empowered the Turkish national subject and established national sovereignty by stressing “Turkish ethnicity, the Turkish language and Sunni Islam” (Dönmez-Colin 14) as the official definition of its citizenship. In addition, the Turkish Republic continued the Ottoman tradition of identifying minorities based on religion rather than ethnicity. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne granted minority rights such as setting up charities and religious social institutions; opening, managing, and supervising schools; having education in one’s own language; and performing one’s own religious rituals only to non-Muslims. Hence, Muslim minorities, which included Arabs, Laz, Syrians, Circassians and Kurds, were denied such benefits. Additionally, because the use of all languages other than Turkish was banned from the public sphere, Muslim minorities were denied the right to speak their own languages, leaving them linguistically mute and culturally non-existent. In other words, Muslim minorities underwent a process of cultural assimilation in the state’s attempt to homogenise the nation. Of these minorities, Kurds constituted the largest and the most problematic.

The 1950s marked the beginning of a change in Turkey’s political, economic and social life when the Democrat Party (DP) came to power, defeating the founding political party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP). The new government focused on industrialisation, economic integration with the West and modernisation in agriculture, which served as the catalysts for the Turkish economy’s gradual transformation from agrarianism to capitalism. Among the results of this structural change was the emergence of different economic classes and rural-to-urban migration. These structural changes allowed a film culture to flourish and reshaped filmmaking practices in Turkey. Cinema, as the major mass entertainment, turned into a profitable medium for investors and Yeşilçam (the name of the Turkish film industry that was influential between the 1950s and 1990s) became its centre and brand. Its primary audience was the working class newcomers who were looking for their own representations on screen.

Representations of Kurdishness in Yeşilçam

Yeşilçam, which has long been defined by and remembered for its melodramas and comedies, dealt with certain anxieties and fantasies of the migrant population through films that took place in both urban and rural settings (Kırel; Güçhan; Maktav). [4] While both melodramas and comedies set in the city communicated anxieties closely related to industrialisation, urbanisation and the emergence of a bourgeois culture, the fantasies were about a classless society where cross-class love and class mobility were possible (Kılıçbay and İncirlioğlu). As class formations became more apparent and class antagonism escalated in the 1970s, coal miners, railroaders and factory workers became protagonists, and films dealt mostly with male working-class anxieties of humiliation and exploitation. Fantasies, conversely, revolved around different ways of remasculinisation (Arslan; Suner).

Until the 1990s, the rural dramas in Yeşilçam depicted the rural/East as hostile, uncivilised, untamed and backward with its snowy mountains, barren lands and hellish steppes; it was a place governed by feudal lords on the plains and by bandits in the mountains. Kurds were portrayed as “the poor illiterate easterners from the mountains. They were identified by the black shalvar (loose pants), their poverty and their lack of proper discourse in the official language” (Dönmez-Colin 91). Their stories/tragedies were mostly economic and/or female-centred, emerging from archaic feudal customs such as başlık parası (bride wealth), kuma (second wife), berdel (bride exchange), bloodshed, smuggling and deprivation of all sorts (Yücel 35–61). Gratification was provided by the acts of the male protagonist in procuring justice, morality and male authority.

Importantly, rural dramas did not address Kurdishness as an ethnic identity. Just as the bourgeois characters in urban films were hostile to all migrants regardless of their ethnic backgrounds, so the feudal lords in rural dramas were hostile to all rural inhabitants. In fact, these films “used Kurdish characters and the geography of their homeland without giving a name or language, but rather with an Orientalizing gaze” (Dönmez-Colin 91). Kurdishness was implicitly evoked by the use of Kurdish names, an Eastern accent and the mention of Eastern cities as characters’ hometowns, thus associating its characters’ identities with a geographical space: the East. The conflict, then, was not ethnic since Kurdish characters were constructed as Turks who live in the East and speak Turkish. The conflict was rather economic in the sense that the East was presented as a hostile and backward place, depriving its inhabitants of any proper education and employment opportunities. Yılmaz Güney, however, represents one particular exception to this generalisation.

Güney was a prolific screenwriter, director and movie star in Yeşilçam (Koçer; Armes). His importance lies in the fact that his films and screenplays, with their explicitly Kurdish protagonists, revolved around the socio-economic struggles of the Kurdish population. They showed how Kurds were deprived of humane living conditions; forced into cheap labour, as in Anxiety (Endişe, Şerif Gören, 1974); driven to madness and annihilation, as in The Herd (Sürü, Zeki Ökten, 1979); or crushed under both feudal traditions and the oppressive state apparatus, as in The Way (Yol, Şerif Gören, 1982). With their bleak endings, Güney’s films raised much controversy at a time when Kurdish identity was not open to any discussion in the political sphere. It was also Güney who used the word “Kurdistan” to signify a homeland for the Kurds in The Way. According to Candan, this was a “very radical and visible self-assertion [that occurred] at a time when Kurdish language, literature, music, broadcasting, etc. was banned in Turkey” (4–5).

Throughout the 1980s, directors such as Bilge Olgaç, Şerif Gören, Zeki Ökten and Erden Kıral continued the Yeşilçam tradition of portraying the East and its oppressive feudal relations with stereotypical characters and cinematography of bandits, snowy mountains, death and impossible living conditions, tropes commonly based on literature (Yücel 107–26). In the early 1990s, film production in Turkey was reduced to almost ten films per year, and Hollywood productions dominated the market. Amidst this turmoil, the domestic market gained back its audience first with The American (Amerikalı, Şerif Gören, 1993) and later with The Bandit (Eşkıya,YavuzTurgul, 1996). Not only was The Bandit Turkey’s highest grossing film until 1996, but it had a Kurdish protagonist and a Kurdish antagonist who were portrayed as two rural ex-bandits from the Mount Judi of Şırnak, a city in the South-Eastern Anatolian region.

The 1990s also witnessed the rise of the “New Turkish Cinema” (Suner 33) and the collapse of Yeşilçam. Unlike Yeşilçam, which was a major mass entertainment industry famous for its melodramas and stars, New Turkish Cinema was defined by the low-budget independent films of young up-and-coming filmmakers and amateur or unknown actors. While Yeşilçam predominantly produced mainstream films about a classless unified society, films of the New Turkish Cinema discussed the concepts of alienation of the individual and the increasing ghettoisation of the cities with a realist style. [5] However, the conflicts were still economic—the city was still contaminated, packed and airless—and the anxieties were still male.

The term “Kurdish Cinema” also emerged in the mid-1990s to discuss productions using the Kurdish language, which had a responsibility to narrate the Kurdish issue with explicit and direct representation (Çiftçi 267). Mutism, or the rejection of speaking, was a common allegory adopted by Güney in his films, and the practice continued into the 1990s, manifesting in films such as The Bandit, to signify the prohibition of Kurdish language. Perhaps the most important common element of “Kurdish Cinema” with Güney’s films was the portrayal of Kurdish characters not as Turks living in the Eastern part of the country, but rather as an ethnic group with different traditions, anxieties, fantasies and language. The 1990s was also the time when Turkish audiences saw the portrayal of Kurdish guerrillas through Let There Be Light (Işıklar Sönmesin, Reis Çelik, 1995). Although the film failed to produce a critique by sticking to a stereotypical, one-dimensional Kurdish protagonist, its attempt to highlight a controversial character is still noteworthy.In terms of the representation of Kurdish identity, the existence of films discussing Kurdishness in the 1990s is extremely important because the 1990s witnessed the escalation of the armed conflict between the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) (Marcus). Any form of cultural product that centred on the Kurdish issue faced much censorship, received very little funding and even fewer distribution opportunities (Oran 181–4). Following this, the 2000s were a period of liberation for the Kurdish language in the public sphere, particularly because of Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative. This does not mean that the suppression of the Kurdish language was over, but the public consensus about the existence of Kurdish as a language was established and the state policies were poised to recognise the cultural existence of the Kurdish population (Tacar 259–60). For example, through its female protagonist who does not speak Turkish, Big Man Little Love (Büyük Adam Küçük Aşk, Handan İpekçi, 2001) brings forth the existence of Kurdish as a native language. Representations of discrimination during this period remained mainly economic, but the film Journey to the Sun (Güneşe Yolculuk, Yeşim Ustaoğlu, 1999), amongst others, began to highlight ethnic discrimination as well through scenes in which the protagonist underwent humiliation and torture because of the colour of his skin, his Kurdish name or his South-Eastern accent.

Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative and Its Reflections in Cinema

AKP officially launched Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative in 2009 but it had been attentive to the Kurdish question since it came to power with the 2002 elections. [6] Most of the initial developments were in the domain of language. Turkey’s first state-owned Kurdish language television station, TRT Kurdi, initially named as TRT 6 (2009–2015) started broadcast in January 2009 and Kurdish was used in election campaigns. AKP passed several pieces of legislation approving, for example, the rights of universities to teach the Kurdish and Zazaki languages and allowing prisoners to speak with their visitors in languages other than Turkish. Other changes followed, such as the construction of an independent human rights institution and the creation of an Anti-Discrimination Committee as well as the implementation of national mechanisms to prevent torture. On 28 December 2012, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan revealed that the National Intelligence Organization (MİT) had been visiting Abdullah Öcalan, the founder of the PKK, in Imrali Prison to find a solution to end the conflict. On 4 April 2013, the government announced the names of celebrities, intellectuals, writers and academics who were chosen for the “Commission of Wise People” and tasked with enlightening the public on the Kurdish Initiative through meetings, talks and symposiums in all seven regions of Turkey. By mid-2015, the process had ended. Nonetheless, its moderate atmosphere created a new cultural space that “allowed old but suppressed issues to be discussed in literature, television programs, music and film, among others” (Köksal 136). [7]

Bearing in mind this new cultural space, we will now discuss My Marlon and Brando, The Storm and Future Lasts Forever. The reasons for the choice of these particular films are twofold: first, these three films were produced on the eve of and during the period of Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative, which opened up a space to discuss and account for the past. Second, each film presents a specific representation of Kurdishness. Rather than depicting Kurds as a minority that are located in the eastern part of Turkey, My Marlon and Brando, considers Kurdishness as a transnational identity that expands the borders of a single country. In The Storm, Kurdishness is reconstructed through the discrimination the male protagonist faces throughout the film. Finally, Future Lasts Forever reverses the Yeşilçam tradition of stereotyping Kurdish characters as illiterate, ignorant and rural, instead portraying a male Kurdish protagonist who is modern, urban and educated.

Kurdishness as a Transnational Identity: My Marlon and Brando

My Marlon and Brando tells the story of Ayça (Ayça Damgacı, who also co-wrote the script), an amateur Turkish actor living in Istanbul, as she tries to reunite with her Kurdish boyfriend, Hama Ali (Hama Ali Khan), who lives in Iraq during the 2003 United States-led invasion. Because of the ongoing war in Iraq, the borders are closed and Hama Ali cannot leave Urmiye. After Ayça fails to reach him by phone, she decides to go to Iraq to find him. Upon arriving at the Iraqi border village, Habur, she learns that the Turkish-Iraqi border has also been closed to transit. Refusing to accept failure, she arranges a meeting with Hama Ali in Iran. Unfortunately, Hama Ali is killed passing over the border from Iraq to Iran.

Figure 1: My Marlon and Brando (Gitmek: Benim Marlon ve Brandom, Hüseyin Karabey, 2008).

Asi Film. Screenshot.

The film depicts Kurdishness as a transnational identity that belongs to no particular country and is described not as a national but a cultural identity that has spread throughout the Middle East. The transnational nature of Kurdish identity is presented through Ayça’s relationships and exchanges with other characters that place her in the middle of a complex territorial and national/ethnical network. First, Hama Ali is introduced to the audience solely as a Kurdish man. In the film, he defines himself with his ethnic identity and calls himself a Kurd rather than an Iraqi. Ayça does not speak Kurdish so they use English as a lingua franca. Second, we are introduced to the Kurdish community in Istanbul when Ayça goes to a Kurdish cultural centre to buy a Kurdish-Turkish dictionary. There, she meets an illegal Iraqi Kurdish immigrant, Soran (Emrah Özdemir), who introduces her to an illegal immigrant community in Istanbul. Later in the film, Ayça meets an unlicensed Kurdish taxi driver in the Kurdish-populated city of Diyarbakir who takes her to the Turkish-Iraqi border town of Habur. There, she comes across a Turkish woman of Kurdish origin who is waiting for the border to reopen so she can meet with her son, who is on the Iraqi side. Speaking only Kurdish, the woman desperately tries to communicate her worry to Ayça through the help of a man who translates their conversation. Finally, we see Ayça, in tears and unable to communicate, sitting inside the small shop of an Iranian Kurdish man near the border. The Iraqi immigrants, the woman at the Turkish-Iraqi border, the Iraqi Kurd Hama Ali and the Iranian Kurdish man at the end of the film become examples of the transnational nature of Kurdish identity. Though Kurdishness is conceived as a transnational identity without borders here, the film still depicts borders as real rather than artificial. Even Ayça, in her unsent letters to Hama Ali, expresses her wish to bomb/destroy the borders to meet with him. In this sense, borders suggest deportation for illegal immigrants, obstacles for Ayça, anxiety for the Kurdish woman waiting in Habur and death for Hama Ali.

In addition to presenting Kurdishness as a transnational identity, the film also discusses ethnicity through Ayça’s indifference to the problems of minorities in general and of Kurdish minorities in particular. Throughout the film, Ayça is exposed to several ethnicities: her Armenian neighbours, illegal Iraqi immigrants, Iranian human traffickers in Turkey and the Kurdish community in Istanbul. She does not contemplate the reasons for her Armenian neighbours’ paranoid behaviours—their constant double-checking of the locks on their doors and windows that suggests a constant state of insecurity and fear. Equally, she ignores the curious suspicion of Kurdish men in the Kurdish cultural centre regarding her interest in the Kurdish language. While the film depicts the miserable living conditions of illegal Iraqi immigrants in Istanbul, Ayça, again, does not seem to register this. When she goes to Soran’s place to take his paintings for safekeeping, the camera records the image of a ruined building with no proper heating or hygiene. Soran lives with seven other immigrants in a suffocating, small room and tells Ayça that four hundred more immigrants reside in the same building. Later in the film, Ayça is depicted as surprised and ignorant when she sees Soran and his friends being arrested and deported on television. Similarly, when the taxi driver on the way to Habur complains about the constant ID checks in the region, she does not see it as a form of discrimination but suggests that they are regular practices. For her, these controls, presented as an example of state oppression, are normal, not something that needs to be problematised. Finally, in Habur, she remains indifferent and uninterested in the Kurdish woman, who desperately tries to communicate her pain. Even though they are not explicitly expressed, all of these side characters face different types of discrimination, and Ayça remains oblivious and blind to them all. Her consistent ignorance becomes a tool with which the Turkish audience may confront and problematise their own supra-identity as Turks.

Identity Construction through Discrimination: The Storm

The Storm depicts the period of the 1990s, a highly repressive decade for political groups—especially the Kurdish movement—characterised by continuous police raids, tortures, kidnappings and extrajudicial executions. The film’s main plot revolves around the reconstruction of the male protagonist’s, Cemal’s (Cahit Gök), identity from that of an Alevi to that of a Kurd. After passing matriculation, Cemal goes to Istanbul from his hometown, Tunceli, to study economics at Istanbul University where he meets with a group of students belonging to the Kurdish movement. Situated in the eastern part of Turkey, Tunceli is a Kurdish-populated city. However, the population commonly defines themselves through their religious identity as Alevi, rather than their ethnic identity. Before meeting the group, Cemal also defines his identity only in terms of religion, but, with their influence, he connects with and accepts his Kurdish identity, finally joining the Kurdish political movement. As one of Cemal’s friends suggest in the film this “slow but radical” awakening of Cemal’s repressed ethnic identity happens because of various forms of discrimination, which are presented throughout Cemal’s encounters in Istanbul.

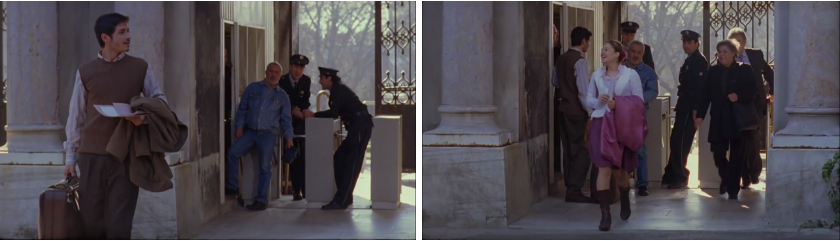

Cemal’s first contact in Istanbul is with the state, through its police force, at the university gate. In the scene, Cemal walks past the security point guarded by both the university’s security personnel and police with a big suitcase and papers in his hand suggesting his new arrival to the city. As soon as he passes the gate, the personnel and the police officer start to make fun of his naivety, as he is expected to show his papers and provide some form of identification. While he looks around the campus fascinated, the security personnel tell the police that he entered the campus “illegally” and it is the police’s duty to question him. The police officer hails Cemal and asks him to show the papers in his hand. Meanwhile a typical modern-looking, urban Turkish family—a blond girl wearing a pink two-piece dress and her parents—walks past the gates without any questions or interrogation. This selective treatment stands as an example of discrimination by appearance. Moreover, after the police officer looks at Cemal’s papers, he asks Cemal to confirm his hometown as Tunceli. [8] He then tells Cemal to leave his suitcase at the gate and not to waste his chance. This suggests that after being identified as a Kurd through his native place, he is immediately considered as a potential suspect for illegal activities and pre-emptively warned to behave well.

Figures 2 and 3: The Storm (Bahoz, Kazım Öz, 2008). Yapim 13. Screenshots.

Cemal’s second encounter is with the Turkish Left. [9] The members approach Cemal to recruit him under the pretence of helping him deal with the university’s bureaucratic processes, but they immediately abandon him after they learn Cemal’s hometown and, hence, his ethnic identity. Later in the film, the Turkish Left is described as having its own political agenda. It organises events such as protesting the Higher Education Council(YÖK) or boycotting canteens, which appear to Cemal as superficial attempts when compared to the traumatic events he experiences throughout the film, such as raids, shootings, tortures and systematic police violence. [10] One could argue that the film, thus, caricaturises the way the Turkish Left takes itself so seriously and suggests the impotence of its political agenda.

Cemal’s third encounter is with the Turkish urban upper class at the university during classes. Their interaction is reminiscent of Yeşilçam films where the male urban upper-class characters look down upon and belittle the male newcomer, lower-class migrant. It is only with the undeniable love of the rich girl towards the poor boy that the rich start to appreciate the values and strengths of the lower class and re-educate themselves. In The Storm, as in a classic Yeşilçam film, Cemal is depicted as an outsider and humiliated for his disoriented, naive and perplexed behaviour by the urban upper class. However, unlike Yeşilçam, which suggest the possibility of cross-class love, the group casts Cemal out despite the affection one of its female members has for him.

Cemal’s final encounter, then, is with the Kurdish group, where he feels welcomed, accepted, and finally becomes a part of a community. This helps him to gradually reconsider and redefine his identity as a Kurd. In the film, Kurdish and Turkish languages intertwine. While in Cemal’s village the spoken language is Kurdish, the Kurdish group Cemal joins in Istanbul use Turkish to communicate among themselves. In this sense, The Storm differentiates from My Marlon and Brando and Future Last Forever, which have Kurdish-speaking characters. It can be suggested, then, that this film discusses cultural assimilation through the internalisation of Turkish language. It is important to highlight the fact that even though the film was produced in 2008, its story is set in the 1990s when Kurdish language was banned in the public sphere. Regarding the use of Turkish language, the film refrains from using particularly controversial words to avoid any legal proceedings or censorship. Instead, The Storm uses a specific jargon that plays an important role in establishing a symbolic belonging. Common, yet politically charged expressions such as çıkış yapmak (making a sortie), bölge (zone) or önderlik (leadership) gain significant meaning and become a common lexicon during the Kurdish group’s conversations referring to guerrillas, Kurdistan, the PKK and/or Abdullah Öcalan. We argue that, similar to the emphasis on cultural assimilation through the usage of Turkish rather than Kurdish among the group members, the need for particular jargon exemplifies the self-censorship mechanism of the film that results from discrimination based on language.

The slow and gradual awakening of Cemal’s repressed ethnic identity occurs not only through ethnic discrimination but also, ironically, through the freedom he experiences in Istanbul. Yeğen conceptualises two seemingly contradictory issues that facilitate Cemal’s redefinition of his identity as “a state of Turkish Kurdishness” (182). Istanbul is depicted as a place that gives Cemal enough experience to reconnect with his repressed ethnic identity. However, this does not mean that he is unaware of the fact that he is a Kurd. At the beginning of the film, in his hometown of Tunceli, he speaks Kurdish with his parents and his mother’s name is Kurdish. However, because everyone in Tunceli experiences ethnic discrimination equally, he does not perceive himself as a part of a minority. For him, being a Kurd is not something that he needs to express and question explicitly and communally. His attitude towards the issue is denial. Only in Istanbul, through the influence of the members of the Kurdish group, does he wonder, for the first time, why his mother’s Kurdish name has been changed into a Turkish name on her identification card. It is again in Istanbul that he realises that ID checks are not applied to every member of the society and that his attire, accent and hometown can make him a target of suspicion. Only after he comes to Istanbul does Cemal witness how people can be humiliated for speaking Kurdish in public. In other words, the freedom of Istanbul makes him realise that the discrimination he has been exposed to is not an experience that the entire society shares—only the minorities. As the discrimination escalates, so does Cemal’s political involvement in the group. The film, thus, suggests that the awareness of ethnic identity is also strongly derived from political belonging; being a Kurd means being politically active. Therefore, The Storm completes Cemal’s transformation with a scene that one might describe as a rite of passage, where he throws a Molotov cocktail into a bank.

The Modern Kurd and Identity Construction through Trauma: Future Lasts Forever

Like My Marlon and Brando, Future Lasts Forever has a female protagonist from Istanbul, a young ethnomusicologist, Sumru (Gaye Gürsel), who travels to the eastern part of Turkey. However, unlike Ayça in My Marlon and Brando, Sumru is from the Hemshin peoples, who speak an archaic Western Armenian dialect, and is thus a minority herself. [11] During her time in Diyarbakir, Sumru meets a Kurdish man named Ahmet (Durukan Ordu), and together they discover an enormous archive of video and audio recordings of the family members of unsolved murder victims. In the process, Sumru remembers her old boyfriend, Harun (Osman Karakoç), who had gone to join the guerrilla fighters a few years ago and never returned, while Ahmet reflects on the death of his father, another unsolved murder victim whom Ahmet describes as “shot in the middle of the street” without providing a context.

Sumru and Ahmet initially meet by chance on the street, where he mistakes her for a tourist and begins to flirt with her. The second time they meet, however, is through the recommendation of a friend, who tells Sumru that Ahmet can help her with her research. After learning that Sumru is working on elegies, Ahmet needles her by saying, “And now the Kurdish people become objects of sociological research, wow!” Ahmet’s response is significant for two reasons: first, it demonstrates a sarcastic and perhaps saddened response to the objectification of the Kurdish people as an interest for academic research by “foreign” researchers, which, in a way, is useless because it does not contribute to any sort of situational improvement in the region. Second, it becomes a kind of self-criticism on the part of the film because the film crew, just like an academic, comes to the area, aims to shoot the best possible film and then leaves the region without addressing the existing problems in any tangible way.

As previously mentioned, for decades Turkish cinema discursively constructed its Kurdish characters as rural, illiterate and uncivilised in their social manners and, if in the city, most commonly as unskilled workers. These portrayals are compatible with the orientalist gaze of Turkish cinema, which depicts the Kurds as an underdeveloped population. Even though Future Lasts Forever similarly portrays Ahmet as an unskilled worker selling pirated DVDs on the streets, it also challenges Yeşilçam’s stereotype. Ahmet is constructed as a literate man who watches Theo Angelopoulos films and imitates Jean-Paul Belmondo from Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960). He is also shown to share the same cultural capital as Sumru. Between them, there is no cultural barrier. Together, they recite poems of Andrei Voznesensky and listen to the recordings of Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad. In terms of social decorum, rather than the stereotypical representation of the Eastern man as volatile and uncivilised, Ahmet is polite and gentle. Overall, he is a typical modern Western man with appropriate social manners and cultural capital, even though he is from the East. Thus, one can argue that Ahmet’s Kurdishness in the film is associated with the trauma of his father’s murder, which is presented as an example of another unresolved social injustice in the region.

Sevcan Sönmez describes Future Lasts Forever as “a film that uncloaks unmourned pains, investigating, gathering together and opening the door to mourning” (29). She analyses Sumru’s position and claims that Sumru discovers her own trauma by learning from others. The initial reason for Sumru’s visit to Diyarbakir is presented as that of gathering elegies for her research. However, after meeting with the relatives of unsolved murder victims and watching the scenes from archival footage at the documentation centre that show violence and chaos in the South-Eastern region, she abandons her initial research. Her interest shifts to documenting the real-life stories of these victims, not collecting elegies about them. One could argue that this process of coming to terms with the past helps Sumru face and overcome her own pain regarding Harun. Sönmez’s analysis, although well-grounded on Sumru’s position, neglects the fact that Ahmet goes through a similar process throughout the film since he is also present in the interviews and at the documentation centre. Ahmet’s past, and the death of his father, is not revealed until almost the end of the film. After the interviews and the days spent at the documentation centre, Sumru tells Ahmet that she needs to go to Harun’s village. Her decision to take action suggests that she is finally ready to come to terms with the fact that Harun is dead and to find his grave. Reluctant at first, Ahmet joins her on the way. Near the end of the film, on their way to Harun’s village, Ahmet tells the story of his father’s death. This suggests that the experience he shared with Sumru unlocked Ahmet’s own pain and trauma; finally, the film reveals why Ahmet is so invested in Sumru’s research and willing to help a total stranger. The reason for the deaths of Ahmet’s father and Sumru’s ex-boyfriend are not clearly explained in the film, but the fact that Harun went to join the guerrillas and the fact that Ahmet’s father’s murder was unsolved suggest that these deaths are related to the Kurdish issue and that the film intends to use them as means to discuss the topic. The shared pain of having lost someone they love is used in the film as a tool that brings Ahmet and Sumru together. Nonetheless, the burden of resurrected agony and the trauma that comes with it are so heavy that it does not leave any ground for a romantic relationship to flourish between them.

While this diegetic process affects both Ahmet and Sumru, it also makes it possible for the audience to witness and dwell on the events shown in the film. During the interviews with the families of the unsolved murder victims, it is not just Sumru who listens to their elegies and the stories of their loved ones’ disappearances. In a dark room, in front of pictures of hundreds of unsolved murder victims, the audience also listens. Moreover, when Ahmet takes her to a documentation centre, where together they watch scenes from archival footage, the audience again participates. The film prefers to show real interviews and archival footage instead of recreating dramatic scenes. This particular style of adopting direct representation with visual and oral history creates a sense of honesty that might help the audience to identify with the issue.

The film was produced during a period of hope and expectation. The AKP government was in the process of taking monumental steps in achieving a solution to the decades-long Turkish-Kurdish conflict. It is possible to see the reflections of the Kurdish Initiative in the film, particularly when Sumru and Ahmet discuss the importance of the archival footage in the documentation centre as evidence when the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions are opened to investigate the human rights violations. In discussing the methods and devices used to come to terms with the past traumas, Sancar argues that there usually emerges a clear “breaking point” (259), such as the end of a war or a change in the system that forces the nation to face its traumas. He also suggests that in Turkey, such a clear breaking point did not exist, and the social/collective memory of Turkey was based on suppression and forgetting (257–60). Two years after the publication of Sancar’s book, the AKP launched the Kurdish Initiative, which could have resulted in the breaking point that would have led Turkey to face its past traumas. Future Lasts Forever, therefore, belongs to a period when the war was over and the time for mourning and restoration had begun. In that sense, the film could have been read as a part of the process of reconciliation, had the Initiative continued.

Conclusion

After the collapse of Yeşilçam, the old paradigm of nonvisibility of ethnicity shifted. The period of Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative in the 2000s provided a moderate atmosphere that resulted in the proliferation of documentaries, short and feature films that discussed Kurdish identity. In this article, we investigated three films produced during the Initiative period that bring forward different representations of Kurdishness. My Marlon and Brando presents Kurdishness as a transnational identity; The Storm investigates how Kurdishness, as a repressed identity, unfolds through various forms of discrimination; and Future Lasts Forever challenges the stereotypical representations of Kurds in Yeşilçam by discursively constructing a Kurdish character as modern and urbanised rather than illiterate, backward and uncivilised.

Figure 4: Future Lasts Forever (Gelecek Uzun Sürer, Özcan Alper, 2011).

Nar Film. Screenshot.

In all the three films, the mountains are used a symbolic homeland for the Kurds. As Sengul argues they “signify either resistance (against suppression) or unconquerability and unreachability (by the security forces)” (8). My Marlon and Brando highlights this symbolism when Hama Ali says, “The mountains are a Kurd’s friend”. This statement is important since mainstream cinema have commonly referred to the people inhabiting the mountains as uncivilised, uneducated and rude. When Hama Ali forms this particular kinship with the mountains, he not only accepts the mountains as a part of his identity but also romanticises it. Moreover, the protagonists in these films finalise their journey in the mountains. In My Marlon and Brando mountains are literally the place where Hama Ali’s journey is finalised since he dies while crossing the Iraqi-Iranian border from the mountains. In The Storm, Cemal goes to the mountains to find hope for resistance. The crane up to the mountains in the final shot of the film glorifies not only the mountains but also this resistance. Finally, in Future Lasts Forever, Sumru faces her past in front of Harun’s grave in the mountains. She takes off the muslin made by Harun’s mother from her neck, ties it to Harun’s tombstone and leaves. The final shot of the film then shows Sumru walking by a frozen mountain lake from a distance. These two consecutive scenes suggest both a relief and a release from her past.

These films owe their existence to the hopeful and fruitful atmosphere that characterised Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative. However, none of the films has an optimistic ending. My Marlon and Brando ends with the silent tears of Ayça, signifying the impossibility of her union with Hama Ali and his death. The Storm ends with the dissolution of the group and Cemal’s journey to join the guerrillas symbolically. Sumru’s journey in Future Lasts Forever is finalised with her arrival to Harun’s grave; the place where she accepts her loss and grief. Consequently, one might conclude that, despite all the apparent progressive developments, the films clearly manifest a lack of confidence in the Initiative. The light at the end of the tunnel is yet to be seen.

Notes

[1] The Kurdish Initiative is also known as the Democratic Opening, the Democratic Initiative, the National Unity Project, the Peace Process, and the Solution Process, among other names.

[2] The Ottoman Empire was abolished in 1922. In 1924, the Caliphate was abolished and the Turkish Constitution was adopted. The Education Bill, which provided secular coeducation, was also passed in 1924. In 1926, the Civil Code provided the legal framework for all other social reforms to flourish. Women were given equal rights in the courts in terms of divorce, inheritance and the custody of children. The Arabic script was replaced with Latin letters in 1928. In 1934, women were granted suffrage.

[3] Atatürk did not start the reform period geared towards Westernisation. Since the mid-1800s, the Ottoman Empire had been going through various changes that could be summed up under reforms during the Empire’s Westernisation.

[4] In addition to comedy and melodrama, Yeşilçam experimented with historical epics, sci-fi and horror. The comedy and melodrama, however, were the most popular and profitable genres.

[5] In her book Hayalet Ev: Yeni Türk Sinemasında Aidiyet, Kimlik ve Bellek, Asuman Suner discusses the films of Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Zeki Demirkubuz, Derviş Zaim, Yeşim Ustaoğlu and Uğur Yücel as examples of New Turkish Cinema.

[6] Even though concrete steps towards tackling the Kurdish question started in 2009, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s speech on 12 August 2005 at a rally in the Kurdish-populated city of Diyarbakır, where he used the term Kürt sorunu (Kurdish question) and declared that the answer to the Kurds’ long-lasting grievances was not more repression but more democracy, could be considered the first time AKP publicly declared its intention to attend to the Kurdish question. This was followed by Beşir Atalay’s (the Minister of Interior Affairs at the time) usage of the phrase “Democratic Opening” for the first time on 31 August 2008. Finally, Abdullah Gül, president of Turkey at the time, used the word “Kurdistan” to define Northern Iraq for the first time on 24 March 2009.

[7] While this was significant for the Kurdish question, it is important to highlight the fact that Kurdishness had been discussed prior to the Initiative. As Güneş and Zeydanlıoğlu note, “the 1960s witnessed a significant increase in Kurdish cultural activities, primarily the publication of cultural magazines and their dissemination to a wider public” (3).

[8] Tunceli (formerly Dersim) is a highly symbolic place because of the Kurdish Alevi uprising against the Turkish government in 1937–1938. The Dersim rebellion was “suppressed with the utmost severity and tens of thousands of Kurds were forcibly resettled in the west of the country” (Zürcher 176).

[9] Within the Turkish Left, there were many different factions with different attitudes regarding the Kurdish issue. The film does not specify which faction of the Turkish Left it presents.

[10] YÖK is an institution established after the 1980 coup d’état that regulates the administrative practices of Turkish universities. It has long been criticised for being an ideological state apparatus that limits universities’ autonomy.

[11] Affiliated with the Hemshin district of Rize in the North-Eastern region of Turkey, this diverse group is generally accepted as Armenian in origin. Originally Christian, this group converted to Sunni Islam during the second half of the fifteenth century.

References

1. Alper, Özcan, director. Future Lasts Forever [Gelecek Uzun Sürer]. Nar Film, 2011.

2. Armes, Roy. Third World Film Making and the West. U California P, 1987.

3. Arslan, U. Tümay. Bu Kabuslar Neden Cemil? Yeşilçamda Erkeklik ve Mazlumluk. Metis, 2005.

4. Candan, Can. “Kurdish Documentaries in Turkey: An Historical Overview.” Kurdish Documentary Cinema in Turkey: The Politics and Aesthetics of Identity and Resistance, edited by Sunem Koçer and Can Candan. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, pp. 1–32.

6. Çelik, Reis, director. Let There Be Light [Işıklar Sönmesin]. Arzu Film, 1995.

7. Çiftçi, Ayça. “Kazım Öz Sineması: Konuşmak, Hatırlamak.” Kürt Sineması: Yurtsuzluk, Sınır ve Ölüm, edited by Müjde Arslan. Agora, 2009, pp. 267–87.

8. Dönmez-Colin, Gönül. Turkish Cinema: Identity, Distance and Belonging. Reaktion Books, 2008.9. Godard, Jean-Luc, director. Breathless [À bout de souffle]. Les Films Impéria, 1960.

10. Gören, Şerif, director. The American [Amerikalı]. Anadolu Filmcilik, 1993.

11. ---. Anxiety [Endişe]. Güney Film, 1974.

12. ---. The Way [Yol]. Triumph Films, 1982.

13. Güçhan, Gülseren. Toplumsal Değişme ve Türk Sineması: Kente Göç Eden İnsanın Türk Sinemasında Değişen Rolleri. İmge, 1992.

14. Güneş, Cengiz and Welat Zeydanlıoğlu. The Kurdish Question in Turkey: New Perspectives on Violence, Representation and Reconciliation. Routledge, 2014.

15. Ipekçi, Handan, director. Big Man Little Love [Büyük Adam Küçük Aşk]. Yeni Yapım Film, 2001.

16. Karabey, Hüseyin, director. My Marlon and Brando [Gitmek: Benim Marlon ve Brandom]. Asi Film, 2008.

17. Kılıçbay, Barış, and Emine Onaran İncirlioğlu. “Interrupted Happiness: Class Boundaries and the ‘Impossible Love’ in Turkish Melodrama.” Ephemera, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 236–49.

18. Kırel, Serpil. Yeşilçam Öykü Sineması. Babil Yayıncılık, 2005.

19. Koçer, Zeynep. “Representations of Masculinity in Yılmaz Güney’s Star Image in the 1960s and 1970s.” Diss. I. D. Bilkent University, 2012.

20. Köksal, Özlem. Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen. Bloomsbury, 2016.

21. Maktav, Hilmi. “Türk Sinemasında Yoksulluk ve Yoksul Kahramanlar.” Toplum Bilim, vol. 89, 2001, pp. 161–89.

22. Marcus, Aliza. Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. NYU Press, 2007.

23. Oran, Baskın. Türkiyeli Kürtler Üzerine Yazılar. İletişim, 2010.

24. Ökten, Zeki, director. The Herd [Sürü]. Güney Film, 1979.

25. Öz, Kazım, director. The Storm [Bahoz]. Yapim 13, 2008.

26. Sancar, Mithat. Geçmişle Hesaplaşma: Unutma Kültüründen Hatırlama Kültürüne. İletişim, 2009.

Sengul, Ali Fuat. “Cinema, Space and Nation: The Production of Doğu in Cinema in Turkey.” Diss. U of Texas at Austin, 2012.27. Sönmez, Sevcan. Filmlerle Hatırlamak: Toplumsal Travmaların Sinemada Temsil Edilişi. Metis, 2015.

28. Suner, Asuman. Hayalet Ev: Yeni Türk Sinemasında Aidiyet, Kimlik ve Bellek. Metis, 2006.

29. Tacar, Pulat Y. “Türkiye İçin Uygulanabilir Sayılan Çokdilli Toplum Modelleri ve Toplumun Çokdilli Yapısının Korunması Yöntemleri.” Türkiye’de Kürtler: Barış Süreci İçin Temel Gereksinimler, edited by Cem Bico. Heinrich Böll Stiftung Derneği Türkiye Temsilciliği, 2009, pp. 257–61.

30. Turgul, Yavuz, director. The Bandit [Eşkiya]. Filma-Cass, 1996.

31. Ustaoğlu, Yeşim, director. Journey to the Sun [Güneşe Yolculuk]. Istisnai Filmler, 1999.

32. Yeğen, Mesut. “Fırtına, Yeniden?” Bir Kapıdan Gireceksin: Türkiye Sineması Üzerine Denemeler, edited by Umut Tümay Arslan. Metis, 2012, pp. 179–89.

33. Yücel, Müslüm. Türk Sinemasında Kürtler. Agora, 2008.

34. Zürcher, Erik J. Turkey: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris, 2004.

Suggested Citation

Koçer, Z. and Göztepe, M. O. (2017) 'Representing ethnicity in cinema during Turkey’s Kurdish Initiative: a critical analysis of My Marlon and Brando (Karabey, 2008), The Storm (Öz, 2008) and Future Lasts Forever (Alper, 2011) ', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 13, pp. 54-68. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.13.03.

Zeynep Koçer is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Design at Istanbul Kültür University. She teaches visual culture, film history, and cultural studies. Koçer received her PhD in in Visual and Cultural Studies from I.D. Bilkent University. Her research areas are Turkish modernisation and politics, cultural studies, reception studies and gender.

Mustafa Orhan Göztepe is a Teaching Assistant in the Department of Communication and Design at Istanbul Kültür University. He received his BA in Communication Studies from Galatasaray University, his MFA in Arts, Philosophy and Aesthetics from University Paris 8 and his MA in Cinema from Marmara University. He is currently working on his dissertation on the representations of minorities in cinema at Bahçeşehir University. His research areas are Turkish politics, postcolonial film studies, ethnicity and nationalism.