Film Festivals as Cosmopolitan Assemblages: A Case Study in Diasporic Cocreation

Monia Acciari

This article aims at discussing film festivals within the wider discourse of cosmopolitan studies. In order to assess film festivals as formed by a variety of cosmopolitan manifestations, I will look at the intersecting nature of film festivals as events, at their programming choices and strategies, at audience responses and at the importance of the filmic texts they exhibit. In doing so, I will start by assessing some recent literature on cosmopolitanism in order to formulate a notion of “cosmopolitan assemblage” that is inspired by the idea of multiple manifestations of cosmopolitanism and by the vision of a universe united in diversity (Fiala 93). The notion of cosmopolitan assemblage will explain the complexity of identity-based film festivals seen as not merely events based on questions of imagined communities (Iordanova, “Film Festival Circuits”), but more completely as events based on a variety of cosmopolitan phenomena.

Over the past two decades or so, the notion of cosmopolitanism has attracted interest across a variety of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. The approach that these disciplines have provided has brought about an updating of the signification of this term from its origins in moral and political philosophy to its status as a core notion in social science, which also includes an evolving and developing interest in debates involving film and media studies (Delanty 5). This article engages specifically with the notion of cultural cosmopolitanism, particularly with debates around multiculturalism, the nation and communities, which I seek to update through discourses on territorialisation and deterritorialisation, or “assemblage” (Deleuze and Guattari 7). Identity-based film festivals have to date been defined by their cultural specificities (Iordanova, “Mediating Diaspora” 13); here, such festivals are studied as creative expressions that challenge the idea of identities as exclusive attachments to a particular culture. In doing so, the study of cosmopolitanism is married with the notion of assemblage to encourage the reading of cultural diversity—the appreciation of multicultural mélange—as being intertwined with the creative processes of film festival programming.

Within the growing intersection of multiple disciplines concerned with the study of cosmopolitanism lies the idea that I intend to explore in this article. By weaving together cosmopolitanism with assemblage and film festival programming, my aim is to converge with Gerard Delanty’s vision of cosmopolitanism, which recognises its potential for interdisciplinarity (3). However, it should be stressed that, although an interdisciplinary approach is essential to reveal the multiple layers of cosmopolitanism, such an approach has also its flaws. The term cosmopolitanism, as applied to disciplines such as political philosophy and ethnography, presents shades of signification distinct from its use in film and media studies. Nevertheless, there is a lot to gain from establishing a dialogue between disciplines while also analysing the evolution of the notion of cosmopolitanism, in order to restore the relationship between highly normative approaches and more empirical ones, thus broadening the field of cosmopolitan studies. Methodologically this article seeks to build on a variety of research approaches, such as textual analysis and audience studies, through the empirical acquisition of data. The aim is to analyse the data and to compensate for the weakness inherent in each individual method. Besides, this methodological approach, as mentioned, aims to address the interdisciplinarity at the core of cosmopolitan studies.

Theoretically, this article departs from the optimistic notion of global citizenship, which, while appearing too abstract to be effectual, can suggest an individual and collective obligation towards human rights and global justice. Cosmopolitanism has been seen as an aspect of globalisation (Hannerz 45; Delanty 8), but within a normative understanding it has been distinguished from globalisation itself, which is not a normative concept per se (Delanty 7). However, these two concepts are not too distant, but rather, in a broader sense, meet in considering the extension of moral, political and cultural horizons of people, societies and organisations. Cosmopolitanism, as a concept that has been widely informed by our need to conceive a broad identity, beyond the idea of “homeland” and encompassing the notion of global scale (Delanty 7), implies an attitude of openness rather than exclusivity, and a vision that emphasises and builds scopes for inclusivity. The exponential growth of and attention to cosmopolitanism is in large part due to the impact of discourses that globalisation and transnationalism have made over the past few years when it comes to evaluating how globally connected the world should be, taking into account multiple perspectives rather than one’s immediate context. As Zlatko Skrbiš and Ian Woodward argue, cosmopolitanism is never an absolute or fixed category (728); it is a dimension of social life that should be actively constructed and understood through practices which involve meaning-making in diverse social contexts (730). Such processes involve communities, collectives and nations, all affiliations to which one can direct a sense of connection and belongingness (Miller 391; Chan 1). Being a cosmopolite is often translated as being a “citizen of the world”, a person “at ease in the world” (Chan 2–3), someone who—as defined by Arjun Appadurai—acquires a certain knowledge of the world that goes beyond the immediate horizon of one’s culture, thus moving beyond cultural, political and symbolic boundaries and expanding their diasporic experience. It is in this spirit that I address cosmopolitanism and film festivals, in order to explore the role that communities with diasporic histories, characterised by the condition of longing for the homeland and by the formation of new homes, play in the programming of an event. The insights emerging from a dialogue between cosmopolitanism and film festivals are attractive in two ways: cosmopolitanism is especially interesting to proffer ideas of mobility and adaptability to new cultures, while film festivals are an “arena of emergence” (Rüling and Strandgaard Pedersen 319) and platforms of structured film culture (Nichols 30).

The programming of the first Leicester Asian Film Festival, held on 16–19 March 2017 in Leicester (UK), is my case study in an examination of festivals as expressions of cosmopolitan practices that are able to create room for various considerations of an institutional as well as cultural nature. By analysing this case study, I observe how the programming of this festival, and my involvement with it, was committed to constructing the idea of a venue characterised by an unlimited crossing of physical and symbolic boundaries. With this in mind, I establish here the idea of film festivals as cosmopolitan assemblage, wherein the notion of border is central to account for the programming process and also the all-inclusive diasporic experience of the event. This idea seeks to provide a less normalised definition of cosmopolitanism and, simultaneously, to engage with instances of symbolic, cultural and transitional border-crossing, all of which, as further explored below, are elements affecting film festival programming.

Constructing a Notion of Cosmopolitan Assemblage in Film Festivals

In Ulf Hannerz’s work, cosmopolitanism is defined as “the willingness to become involved with the Other, and the concern with achieving competence in cultures” (239–40). By keeping this in mind, and in the midst of cultural diversity and a divided world, cosmopolitanism seeks to build on the virtuousness of the human experience. This article argues, by means of a sociological and textual approach, that film festivals should be placed at the centre of the larger debates on cosmopolitanism, especially because some festivals are cultural events built by multiple diasporic experiences. Furthermore, by setting up a dialogue between film festivals and cosmopolitan studies in order to upgrade the conception of identity-based festivals, this article reappraises Marijike de Valck’s definition of these festivals as events committed to political causes that transcend borders and intervene by circulating images at the supranational level (de Valck, “Film Festivals and Migration” 1502). On these festivals, de Valck writes that “they aim to influence identity building, for example by community outreach or countering prejudices and ethnic stereotypes, and foster what Benedict Anderson called imagined communities” (1503). Dina Iordanova provides a more comprehensive account of diaspora-linked film festivals. Iordanova distinguishes between three types of film festivals: cultural democracy festivals, which are organised with national support; identity agenda festivals, which have specific functions such as fostering supranational communities and engaging in the struggle to unite a dispersed population, establish nationhood or increase identity awareness; and business and diaspora festivals, which are self-referential events normally sustained by diaspora entrepreneurship in the form of local businesses (“Mediating Diaspora”). Beside Iordanova’s selective categorisation of diaspora-based festivals, I propose a more flexible reading that is the one favouring a citizen’s approach, wherein the citizen/spectator plays an active role in the evolution of the event. It is important to study festivals as events able to contribute to the circulation of “other” images of a changing nation, and to the crossing of its geographical and symbolic borders. They also play a role in deepening one’s awareness of transnational differences and connections, fostering a cosmopolitan attitude, in which migration is considered to be a fluid element of life rather than a fixed perception of cultural identity.

Implicit in some recent studies of cosmopolitanism in cinema, and in cosmopolitan cinema itself, are the notions of borders, mobilisation and identity, all complex categories that affect and problematise the relationships that define the social and cultural processes of the current transnational and global condition of interconnectivity. [1] Maria Rovisco refers to the complexity of mobilities and cosmopolitanism as two research paradigms that are intrinsically connected, an argument that the author elaborates in parallel with Kira Kosnick. The latter writes that contemporary cosmopolitanism relates to a world of flows, rather than a world made up of imagined boundaries, a view that also chimes with that of Mimi Shellar, who emphasises that mobility is the core of cosmopolitanism and that it “owes everything to the mobilities of people, cultures, and ideas around the world” (361).

This article, in line with the new research agenda on cosmopolitanism that calls for an upgrading of the terminology associated with human and cultural mobilisation related to cosmopolitan experiences (Delanty; Rovisco), seeks to unpack cosmopolitan attitudes within “new wave Indian cinema film festivals” (Acciari, “Film Festivals” 17). A central question is weather, by looking at the evolution of new wave Indian films across the world and observing the cultural, social and political barriers that certain films have experienced within the panorama of cinema distribution in India, it is possible to identify film festivals as “bordered” symbolic events of a nation in progress, as well as spaces of diasporic dissent. This question will be addressed by exploring the term “cosmopolitan assemblage” along with assessing the notion of assemblage itself. The latter will be used throughout this article to imply a particular understanding of cultural cosmopolitanism, border-crossing and the reimagination of the immediate horizon of one’s culture over a new diasporic one.I propose, indeed, to read film festival programming as affected by acts of border-creation (in the sense of defining a realm) and border-crossing under the umbrella of cosmopolitan assemblage. I capitalise on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s idea of assemblage to unpack both “forms of content” and “forms of expression” affecting film festival programming (77). Assemblages, the authors write, are composed of heterogeneous elements that enter into a relationship with one another. These elements are not all of the same type; they can be material objects, happenings and events, and also signs and words. While there are assemblages that are composed entirely of bodies, there are no assemblages composed entirely of signs and utterances. An assemblage comprises human and nonhuman bodies, actions and reactions. Within the collation of bodies, Deleuze and Guattari state that assemblages are not static acts but rather events characterised by the double process of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation. While deterritorialisation is defined as being characterised by the departing of elements from a given context, thus constituting disconnection from that original context, reterritorialisation describes to some extent the opposite mechanism, which is the influx of elements that generate new articulations and formations. Such “migration” creates new assemblages.

Deleuze and Guattari’s approach allows me to expound certain experiences of cultural mobility and cross-cultural engagement that are capable of revealing cosmopolitan ways of thinking about and planning film festivals. This cosmopolitanism is not a matter of assessing one migratory condition and identity over another as capable of producing a coherent festival programming, but rather a question of revealing the complexity of entering and exiting imaginary borders and contexts. These diverse clusters of mobility are the elements necessary to start theorising cosmopolitan assemblage.

This article, therefore, shifts the focus away from reading and understanding cosmopolitanism as intersecting film festivals by means of discourses on the internationalisation of Asian film festivals (Nornes) or by depicting such internationalisation using a form of cartography of festivals (de Valck and Loist). These evaluations are firmly rooted within debates of transnationalism (Elsaesser; Nornes). I propose instead to move towards the inclusion of the term “community”, that is, not only the imagined communities as addressed by Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, but also the communities within a city and their histories. Community involvement informs the new research agenda on cosmopolitanism and film festivals and is here the bridge that links the two disciplines.

Reading film festivals via debates on cosmopolitanism provides a fresh view of film festivals as not necessarily and entirely confined within discourses of transnational mobility. By addressing some of the categories of cosmopolitanism, rather than selecting one approach over another, a conversation is created between various perspectives, such as those that emphasise the ability to produce public dialogue and an engagement with cinema that places national and global tensions at its core (Devasundaram 18).

The First Leicester Asian Film Festival: A Case Study

Film festivals are events that are situated at the crossroads of multiple institutional strategies, and at the intersection of technology, commerce, art, ideology and community (Iordanova, “Film Festival Circuit” 23). It has been widely argued that film festivals are events able to bring together multiple constituencies, reflecting divergent sets of standards, and acting, as Lucy Mazdon reminds us, as spaces of global “travel and exchange” (23) and, although happening within a specific city, these are also “site[s] of dwelling and travel” (24). These events are often defined as transient organisations (Iordanova and Rhyne; Iordanova and Cheung), wherein diverse cultural, aesthetic and economic values are attached to the film industries they host, thereby satisfying the need for the emergence of other socio-ethnic discourses.

Conceptually, film festivals lend themselves to be understood as “field configuring events” (Lampel and Meyer 1025) and as transient organisations that “encapsulate and shape the development of … technologies, markets and industries” (1026). I would like to broaden these frames and highlight that festivals are often spaces that develop a cultural dialogue with some communities within the city. Such events engage with the diasporic status of the community not only at a level of “shaping identities” (Iordanova, “Mediating Diaspora” 14) or as a transcultural mediator for what is lost (the homeland) or as celebratory events of the cultural diversity of a city (Acciari, “Film Festivals”). Festivals should be read as cultural and social phenomena that, with reference to my particular case study, can connect (or disconnect) the diasporic condition with (or from) those forces that underpin the emergence of current new wave Indian cinema.

As I already discussed elsewhere, indeed, the emergence of new wave Indian cinema film festivals demonstrates the need for a certain industry from India to find not only new audiences in and outside the country, but also alternative channels of distribution (Acciari, “River-to-River”). Being the associate director of the first Leicester Asian Film Festival, I was faced with the privilege and the challenge of showcasing independent South Asian cinema to the large and historical Gujarati diaspora in Leicester. Curating a film festival is an exciting creative moment and a cultural challenge too. To provide a backdrop to this festival, the Leicester Asian Film Festival (henceforth LeAFF) branched out from the more established London Asian Film Festival (LAFF), which has celebrated and showcased independent productions from South Asia for about twenty years. Being the most enduring event in Europe of films from South Asia, this festival laid the foundations for other festivals of this kind to emerge, from 2000 onwards: first, the Florence Indian Film Festival in Italy, followed by the Indisches film festival Stuttgart in Germany. LeAFF was an event created in collaboration with an array of partners with a variety of visions, who have all come together to work collaboratively, to create a twin event. [2] I will call these kinds of events “franchise events”—that have the ability to extend the temporal and spatial frame of a film festival as is normally conceived. [3] The LeAFF, along with the Edinburgh Asian Film Festival (EAFF) franchise events, are the two reterritorialised festivals that constitute a narrative of migration to and from different cities in the UK. These festivals carry with them a selection of specially curated films that are at times refashioned to meet the needs and particularities of the diverse sociocultural infrastructure of a city, while concurrently participating in the process of global film circulation.

Programming the LeAFF was an exercise that allowed me to select from the abundance of film productions from South Asia for the audience of Leicester. The selection process did not happen independently but was a collaborative effort with other subjects, namely Phizzical, LAFF, Tongues on Fire and Phoenix and the community in the city. I was called on to tailor a selection of films that could connect my personal taste with the longing by the South Asian community of the city to be represented, acknowledged and narrated. In order to devise a programme that could take into account the diverse nuances of a diasporic state, I was able to organise a preparatory event in the community neighbourhood centre, Belgrave. The event aimed to challenge established film preferences and the history of film screening in Leicester centred on imported Bollywood films. For the Gujarati community, I programmed Queen (Vikas Bahl, 2013), a film that has heightened awareness of a new wave Indian cinema. Following the screening, which was attended by about one hundred people, a brief questionnaire was used to measure the audience’s response. While a large number of spectators (circa eighty-three out of one hundred) voiced the necessity for Leicester to have more film screenings of “this kind of cinema from India where women have a central role” (Respondent 23), and commented that “it is great to see films from India that are not only Bollywood films” (Respondent 1), other members of the audience mentioned that “this film does represent a kind of India that it is not yet back home, but it is here” (Respondent 9).

This work emerges from my ongoing project “Building Audiences”, which seeks to address not only the programming of films and the very need of inclusively building audiences, but also to work collaboratively and creatively with the audience itself. Part of this project is currently being documented on buildingaudiences.org.uk, a research website that aims to record the variety of events capable of building a renewed idea of audiences for film festivals. The project is a window wherein to document how to educate communities about new wave Indian cinema, rebuild a renewed cinema-going culture for South Asian communities in Leicester, support venues and theatres in building new South Asian audiences, and set Leicester as a case study. This research, which seeks to explore new creative ways of thinking about cosmopolitan audiences, was propaedeutic to get a feel for the taste of the wider community while programming the festival. The success of the festival lay in the alliance of personal taste (Bosma 70)—used as a parameter to build an adequate programme, the starting point of the creative process—with a diverse set of constituencies, such as the consideration of the histories of cinema-going in Leicester and the creative relationship with the community in the city. The assemblage of these diverse features that affected the programming of the festival stems from a diversified idea of border(s) which they all have in common; histories of South Asian cinema-going in Leicester have been mapped and individuated within a well-defined urban area, highlighting a bordered experience of this practice. The relationship that I have established with the South Asian community in the city has been built through the preparatory event with elements that had the scope to rehabilitate the locus of communal encounter—the community Belgrave Neighbour Centre located within the Golden Mile—as a core space to restore cinema-going practices. [4] The collection of focused feedback allowed me to record the overall sentiments and, more importantly, the desire of this community to engage with new cinema from India, away from the mainstream Bollywood cinema; with a cinema that could speak about the evolution of their society, their diasporic path, their break with tradition and yet their ability to remain within the comfort zone of a neighbourhood centre.

The engagement with the community, the organisation of film screening event prior to the main festival, along with the physical travelling to reach spectators in their “comfort zone”, influenced the programming and significance of the festival. The organisation of film screenings that relocated the very experience of film viewing to the neighbourhood centre provided a disconnection from the “original” film-viewing context: the film theatre. Simultaneously, the screening of new wave Indian cinema to an audience accustomed to the distinctive image of the Bollywood industry and regional cinema awakened in them the desire for new films. The LeAFF, physically, socially and culturally, sat at the intersection of multiple cosmopolitan experiences of border-crossing that are reflected in the changing physical screening localities, in the reterritorialisation of cultural identities and in the conceptual borders at the heart of the selected films, which foster the idea of a nation in flux.Border zones have been largely regarded as a term of securitisation (Shellar 350)—as a border that prevents those considered undesirable from entering a given community or country. In more recent accounts, these same borders have been read as territories that are softer and more malleable (Rovisco), as sites of intense connectivity, cultural mingling and negotiation of differences. It is precisely in the idea of LeAFF as a malleable site, with its multiple cultural variables and its cocreative programming, that the notion of a film festival as a “cultural border” resides. This approach opens up a range of readings for an identity-based film festivals research agenda, positioning these events as central to cosmopolitanism. LeAFF needs to be seen as a case-study festival with an active role, a milieu able to create a discourse on “film festivals as borders” where social, cultural and political transformations may occur. The study and experience of LeAFF lends itself to the observation of the complexity of localities, the borders of the diverse constituencies that formed this festival, and engages with the language and expression of community needs. Thus, the notion of film festivals as border spaces allows us to reflect and articulate the importance of a community, within the grammar of cosmopolitan events.

Recent debates on film festivals have highlighted the option of suspending “the close scrutiny of film as text for the sake of bringing in awareness of the multiple other dimensions of film culture” (Iordanova, “Film Festival Circuit” 23). As much as this is fascinating, I would like to insist on the importance of the analysis of the filmic texts. Films are fundamental resources for awakening an awareness of a language (in development) that scrutinises the variations of cosmopolitanism in relation to the discourse on film festivals. Studying the films programmed at the festivals using a textual approach is to honour the very nature of each film through the tracing of novel perspectives. In this context, it is worth considering how borders and mobility are articulated in these texts and, further, how these films trace symbolic borders to overcome political conflict and social changes.

LeAFF comprised seven films, which explored the complexity of borders and the associated human experience across a variety of narratives, stories and histories. Films such as Mantostaan (Rahat Khazmi, 2016), and Mango Dreams (John Upchurch, 2016) present evocative views on the theme of partition that historically and geographically address the idea of boundaries and the crossing of them. Here, I will concentrate my attention on the study of Lipstick Under My Burkha (Alankrita Shrivastava, 2016), a film labelled as controversial due to the censure that affected its release in India, which occurred a few weeks prior to the beginning of the festival. The film was, interestingly, produced shortly after the production and release of the BBC documentary India’s Daughter (Leslee Udwin, 2015), a critique of the lack of interest in women’s rights that relays the story of a 23-year-old medical student being raped and murdered in Delhi. Lipstick Under My Burkha addresses, through the language of desire and social challenge, the repression of many affected by the bordered geographies of oppressed personal lives, suffering the tension between traditional versus modern societal values.

The filmnarrates the story of four women from different religious backgrounds: a college girl wearing a burkha and fighting the orthodoxies of her family, a Muslim mother-of-three facing domestic rape and marital infidelity, a young beautician escaping the “certainties” of an arranged marriage, and an ageing widow in search of youth and pleasure. The protagonists are neighbours living within a small community in Bhopal, and are driven by their diverse desires to assert personal, sexual and social rights; they find themselves living their lives on the border of what is socially accepted and what is not, outlining societal conflicts and geographies within the emotional microcosms of pleasure and desire. The film is a symbolic journey, a subgenre that uses the idea of a personal and intimate introspection to investigate the significance of borders and mobility, from other perspectives that are not necessarily geographical in a cartographic way. Rather, the film, through subjective experiences, adds another layer to a larger cosmopolitan picture. The encounter of the four women with diverse people within the society—a charming swimming teacher, a passionate lover, a young Sharukh Khan-like musician and a beautiful un-burkha-ed rival in love—punctuate the inner journeys of the four heroines, offering an insight into different aspects of women in Indian culture and politics, under the ruling of a society in turmoil. In line with a variety of films that have recently emerged within the prosperous independent Indian panorama treating the liberalisation of women in India—discourses enforced also by the emergence of activist groups such as the Gulabi Gang—Lipstick Under My Burkha addresses the story of many women.

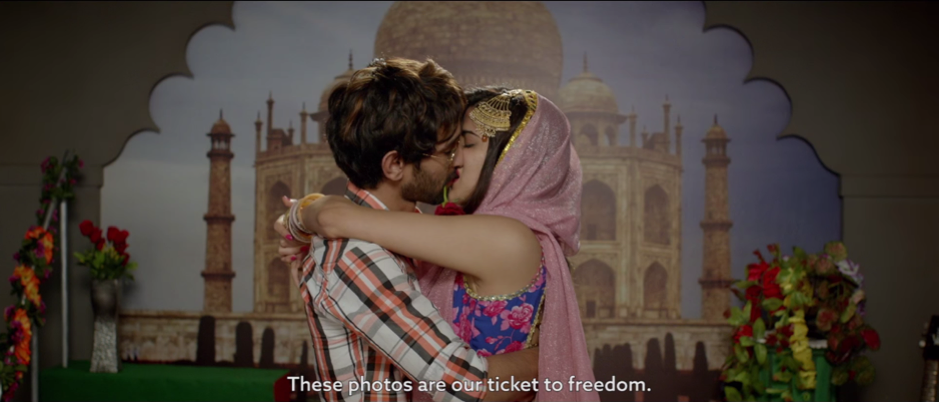

Cosmopolitan engagement with this image of restriction and lack of societal acknowledgement is enabled by an aesthetic of repetition that develops the narrative of a book on the lives of the four women, all looking for a form of independence and an assertion of their being valued citizens; they symbolically migrate from the discomfort of traditional requirements towards the comfort of transgressive identities. The symbolic-journey-film subgenre articulates the experiences of these four women across the city and the desire to migrate to another place (Figure 1) as well as to travel in an imagined and lost time (Figure 2). Interestingly, the multiple migratory experiences, which march in tandem with the sense of a changing society in the film, were also articulated in the response of female audience members answering to my questionnaire. While many of the respondents mentioned their experiences as migrants, Respondent 13 narrated that, “while migrating from India to Uganda and from Uganda to Leicester, we all went through a shift that not only changed our homes and our lives, but also and especially our social status in this city. Being part of the very early group of migrants, we had to struggle and affirm our presence, particularly as women.” Respondent 22, similarly to many other female respondents, explained: “the film reminds me when I first moved to this country, I was learning to be a new woman in a new place.” Another respondent expounded: “it is important to see how women are significantly addressed in this film, I feel one of them, perhaps I was one of them at the time I moved from Kenya to Leicester in 1970. And, this festival is all about our experiences” (Respondent 35).

The motifs of self-discovery in Lipstick Under My Burkha and of social learning in contact with a kind of otherness (Mazierska and Rascaroli) is their own alien embodiment of tenets within a secular society of rules. The focus on this film and observation of LeAFF enables a discussion of mobility and the crossing of borders that identifies a new dimension of identity-based film festivals, as well as defining a tailored programming practice that does not necessarily unpack imagined community experiences (Iordanova), but articulates the different layers of diasporic histories—which include multiple migrations, the development of new identities and the affirmation of social status.

Figure 1 (above): Leela (Aahana Kumra), being forced into an arranged marriage, plots to elope with her lover to Delhi.

Figure 2 (below): Oneof the protagonists, Usha (Ratna Pathak), rejuvenates her image and meets her young dream lover at a fair. Lipstick Under My Burkha (Alankrita Shrivastava, Prakash Jha Productions, 2016). Image source: Film Frame.

This film festival, moving away from being merely a site for an imagined community (Iordanova and Rhyne), is a place of assemblage in which the experiential dimension of the festival and its programming are informed by the double process of deterritorialisation—that is, the disconnection from the original context (here, India)—and reterritorialisation—that is, the arrival of new elements that generate a new formulation and articulation of identity. It is the expansion of the individual experience—the movement beyond cultural, political and symbolic boundaries—that defines the nature of the cosmopolitan assemblage, which here is intrinsically embedded within the nature of this festival. LeAFF is able to update the very notion of migration and border-crossing—in the case of the film analysed—through the disguising of human desires. A narrating voiceover actualises the characters’ desires and is often used to emphasise the subjective experience of this symbolic mobility from the point of view of the four protagonists. Their inner journeys, along with the imagination of other geographies, work as a narrative device to comment on the social condition of women in Indian society. There is a marked sense of duty observance and the normativity of patriarchal borders; all these are lines to be crossed and challenged in an India that is nevertheless depicted as a large and hard-to-delimit borderland, where different voices and cultures mix and clash simultaneously. While the burkha bestows women with some agency and individuality by concealing from the public eye the forbidden varnished nails, adornments and lipstick, in the film it symbolically constitutes the very first critical term that confines identity and self-expression. The protagonists portray the subjugation of the women of South Asia, complicated by the use of and reference to a piece of clothing as a signifier for the oppression of thoughts and identities. Arguably, this film is an important text able to engage with cosmopolitanism that takes into account other less recognisable categories of migration, such as the migration from patriarchal values, to the extent that it succeeds in giving a voice to the “other” whose access to cultural dialogue is severely limited. Lipstick Under My Burkha was also a moment to reflect on and remember the personal migration histories that interweave with the making of new diasporic identities in the city.

Conclusion: Programming Films and Cosmopolitan Assemblage

The fundamental challenge that I faced as a film festival curator consisted of managing and negotiating the aims and work of a lot of different people over several days, as well as curating and managing multiple expectations. How was it possible to please everyone? By specialising and focusing on specific audiences and the interests of a minority ethnic population and the diasporic communities, I was able to achieve what Iordanova and Cheung describe as the tools of diplomacy: the promotion of a particular identity agenda, the exploration of the economic potential of diasporic events and the fostering of ethnic minority talents. The decision to respond to the large ethnic minority of Leicester was translated into a practical approach that would directly involve the creative taste and sense of the community. The central characteristic of a film festival, its spatiotemporal limitation, was challenged with a screening—within the Golden Mile—to involve the community in a form of preselection process that could give me an insight into the preferences of the community and the choices that they would accept. By screening Queen, I could collect information on their reactions, thus assessing what could function or not in a festival for this city. The responses received in about a hundred questionnaires were pivotal to understand a little more about the needs of this community. Responses such as: “We want to see more films from India on women” (Respondent 18) or “We watch enough Bollywood at home; I moved to Leicester 40 years ago, and films like Queen are new and refreshing. They say something new about India that is changing” (Respondent 18) or “It is an India I did not know, I would like to see what is out there now” (Respondent 35) increasingly shaped the idea of a collective preference. It was catering for this collective predilection, in combination with my own, that enabled an extraordinary programming exercise that mobilised patterns of temporal and spatial disposition in the organisation of film festivals. In chorus with the films selected, the idea was to compose a programme that could express persuasive experiences regarding social problems and historical memory to create awareness and stimulate interaction with the public.

Linked with the idea of programming with communities, the films selected for this festival engaged with the social history of the community, to form an overall cosmopolitan narrative of assemblage. While symbolic terms of mobilisation are visualised and represented in Lipstick Under My Burkha, Mantostaan or Queen, the very act of programming with and for the community challenges the assumption that programming is a solo action (Bosma). Programming films for festivals that have as their objective the challenging of fixed borders and that textually move across boundaries of what is accepted and denied within a society is to embrace the possibility of making meaning and addressing a multilayered and intricate cosmopolitanism and citizenship. The programming of the LeAFF has essentially happened by building a participatory narrative that saw the diasporic rehabilitation of a community scarcely acknowledged by the local cinema circuits in Leicester, which is now involved in the very creative act of coprogramming. LeAFF challenged international censoring bodies, included matters of borders at its very core, and built an idea of cosmopolitanism that is not rooted in fixed secular perspectives but rather springs from a flexible and varied viewpoint. The strategies that have governed the programming of the festival have entwined the mobilisation of national causes—among which was women’s freedom of movement and expression—with the framework of an international panorama. This approach has accommodated, within the conception of this festival as a border, the dialectic of exclusion and inclusion of diverse elements that inform the nature of mobile identities. Social causes have been deterritorialised from their country of origin and reterritorialised within an international—diasporic—context. Such reterritorialisation is acknowledged also by the respondents participating at the festival. It determined how the status of being a woman and a migrant from India to Uganda and Kenya, and to Leicester, along with the condition of being part of a diaspora, underpinned liquid identity (Bauman), multiple citizenship and the geographical and moral crossing of boundaries that transcend secularist positions. The interactions of these various elements of a citizenship in transition are those informing the cosmopolitan assemblage at the heart of the programming of this festival.

Programming is a crucial process affecting the creation and management of the film festival’s identity, along with its orientation and, therefore, its uniqueness. Studying film festival programming offers the opportunity to address some of the challenges posed by identity-related festivals (LGBTQ, ethnic, diaspora film festivals). In these specific contexts, the film selection involves the communities and their identities in transition, in tandem with curatorial practices, to provide a renewed agenda for programming practices.

Film festivals are both symbolic and material spaces, which narrate at the same time constraints and movements, encounters and the crossing of boundaries for multiple categories of participants, and for multiple cosmopolitan constituencies. The intricate organisation of time, space, people and objectives inherent in the construction of a film festival relies simultaneously upon mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion. In this article, the observation of the LeAFF as a case study and the analysis of one specific film out of the seven programmed, along with the analysis of audience feedback, allowed me to propose (and experience) the reading of certain film festivals as border territories offering an updated perspective on film festivals as a network with nodes, flows and exchanges (de Valck, “Film Festivals”; Elsaesser). Moving on from the analysis of film festivals as networks, this article proposed the image of festivals as borders (both physical and metaphorical) to be crossed and challenged under the umbrella of an assemblage of cosmopolitan stances. This view seeks to renovate the grammar of film festivals’ time, space and traditional programming modalities (Bosma), and confer on them an identity framed by fluidity, exchangeability and multiple functionalities (Deleuze and Guattari).

In this article, I argued for film festivals as borders, positing that the cosmopolitan assemblage should be understood as a means of shaping specific identity-related festivals that seek to take into account multiple modalities of citizenship. By embracing a textual and sociological approach to unpack this concept, I suggested that, by directing the research of identity-related festivals to their condition as festival-borders, it is possible to identify cosmopolitanism at the core of their modus operandi. Such an approach is capable of generating a public dialogue that has an impact on the audience, from the perspective not only of reception but also of creation. I argue that, while borders and mobility are experienced by a large range of interlocutors (audience, the media and the organising crew), film representations also have implications for the development of the cosmopolitanism of film festivals, as they enable continuous dialogue (inside and outside the screening room) with “others” who do not otherwise have easy access to cultural dialogues.

Notes

[1] See Rovisco, who describes migration flows, transnational experiences and global interconnectivity as being at the core of a cosmopolitan filmic experience. See also Chan, who interrogates aspects of identity, cultural boundaries and national cinemas in light of a cosmopolitan determinism.

[2] The partners participating in this festival are multiple; specifically Phizzical Production, De Montfort University, CATH Research Centre, Tongues on Fire, British Film Institute, London Asian Film Festival and Film Hub Central East.

[3] The idea of franchise events is explored and applied in the broadest sense here, where a selection of the same films is temporally, spatially and ideologically reterritorialised across the nation, and across a variety of diverse cities.

[4] The Golden Mile in Leicester is the name given to a stretch of the Belgrave Road in North Leicester. It is an area dominated by South Asian shops, such as Indian restaurants and saree shops. This area is also famous for the celebration of Diwali with the switching on of lights during wintertime.

References

1. Acciari, Monia. “Film Festival and the Rhythm of Social Inclusivity: The Fluid Spaces of London and Florence Indian Film Festivals.” Cinergie, vol. 2, no. 6, 2014, pp. 15–24.

2. ---. “River-to-River Florence Indian Film Festival: The Italian Response to Bollywood Cinema.” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014, 231–7.

3. Appadurai, Arjun. “Cosmopolitanism From Below: Some Ethical Lessons From the Slums of Mumbai.” Jwtc: Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism, vol. 4, 2001 jwtc.org.za/volume_4_arjun_appadurai.htm. Accessed 12 July 2017.

4. Bauman, Zigmunt. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press, 2000.

5. Bosma, Peter. Film Programming: Curating for Cinema, Festivals, Archives. Wallflower/Columbia UP, 2015.

6. Chan, Felicia. Cosmopolitan Cinema: Imagining the Cross-Cultural in East Asian Film. I.B. Tauris, 2017.

7. de Valck, Marijke. “Film Festivals and Migration.” The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration, edited by I. Ness, Vol. 3, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1502–4.

8. ---. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam UP, 2006.

9. de Valck, Marijke, and Skadi Loist. “Film Festival Studies: An Overview of a Burgeoning Field.” Dina Iordanova and Ragan Rhyne, Film Festival Yearbook 1, pp. 179–215.

10. Delanty, Gerard. “Introduction: The Emerging Field of Cosmopolitanism Studies.” Routledge Handbook of Cosmopolitanism Studies, edited by Gerard Delanty, Taylor & Francis, 2012, pp. 1–8.

11. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi, U of Minnesota P, 1987.

12. Devasundaram, Ashvin Immanuel. India’s New Independent Cinema: Rise of the Hybrid. Routledge, 2017.

13. Elsaesser, Thomas. “Film Festival Networks: The New Topographies of Cinema in Europe.” Dina Iordanova, The Film Festival Reader, pp. 59–68.

14. Fiala, Andrew. Secular Cosmopolitanism, Hospitality, and Religious Pluralism. Routledge. 2017.

15. Hannerz, Ulf. Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. Routledge, 1997.

16. India’s Daughter. Directed by Leslee Udwin, BBC, 2015.

17. Iordanova, Dina. “Choosing the Transnational.” Frames Cinema Journal, no. 9, Apr. 2016, framescinemajournal.com/article/choosing-the-transnational/.

18. ---. “The Film Festival Circuit.” Dina Iordanova and Ragan Rhyne, Film Festival Yearbook 1, pp. 23–39.

19. ---, editor. The Film Festival Reader, St Andrews Film Studies, 2013.

20. ---. “Mediating Diaspora: Film Festivals and ‘Imagined Communities’.” Film Festival Yearbook 2: Film Festivals and Imagined Communities, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, St Andrews Film Studies, 2010, pp. 12–44.

21. Iordanova, Dina, and Ragan Rhyne, editors. “Introduction.” Dina Iordanova and Ragan Rhyne, Film Festival Yearbook 1,pp. 1–18.

22. ---. Film Festival Yearbook 1: The Festival Circuits. St Andrews Film Studies, 2009.

23. Iordanova, Dina, and Ruby Cheung. “Introduction.” Film Festival Yearbook 2: Film Festivals and Imagined Communities, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, St Andrews Film Studies, 2010, pp. 1–20.

24. Kosnick, Kira. “Cosmopolitan Capital or Multicultural Community? Reflection on the Production and Management of Differential Mobilities in Germany’s Capital City.” Cosmopolitanism in Practice, edited by Magdalena Nowicka and Maria Rovisco, Routledge, 2009, pp. 161–80.

25. Lampel, Joseph, and Alan D. Meyer. “Guest Editors’ Introduction: Field-Configuring Events as Structuring Mechanisms: How Conferences, Ceremonies, and Trade Shows Constitute New Technologies, Industries, and Markets.” Journal of Management Studies, vol. 45, no. 6, 2008, pp. 1025–35.

26. Lipstick Under My Burkha. Directed by Alankrita Shrivastava, Prakash Jha Productions, 2016.

27. Mango Dreams. Directed by John Upchurch, Jack Films, 2016.

28. Mantostaan. Directed by Rahat Kazmi, Aaditya Pratap Singh Entertainments, 2016.

29. Mazdon, Lucy. “The Cannes Film Festival as Transnational Space.” Post Script, vol. 25, no. 2, 2006, pp. 19–30.

30. Mazierska, Ewa, and Laura Rascaroli. Crossing New Europe: Postmodern Travel and the European Road Movie. Wallflower/Columbia UP, 2006.

31. Miller, David. “Cosmopolitanism.” The Cosmopolitanism Reader, edited by Garrett Wallace Brown and David Held, Polity, 2010, pp. 377–92.

32. Nichols, Bill. “Global Image Consumption in the Age of Capitalism.” Dina Iordanova, The Film Festival Reader, pp. 29–44.

33. Nornes, Abé Markus. “Asian Film Festivals, Translation and the International Film Festival Short Circuits.” Dina Iordanova, The Film Festival Reader, pp. 151–6.

34. Queen. Directed by Vikas Bahl, ViaCom, 2014.

35. Rovisco, Maria. “Towards a Cosmopolitan Cinema: Understanding the Connection Between Borders, Mobility and Cosmopolitanism in the Fiction Film.” Mobilities, vol. 8, no. 1, 2013, pp. 148–65.

36. Rüling, Charles-Clemens, and Jesper Strandgaard Pedersen. “Film Festival Research From an Organizational Studies Perspective.” Scandinavian Journal of Management, vol. 26, no. 3, 2010, pp. 318–23.

37. Shellar, Mimi. “Cosmopolitanism and Mobilities.” The Ashgte Research Companion of Cosmopolitanism, edited by Magdalena Nowicka and Maria Rovisco, Routledge, 2011, pp. 349–65.

38. Skrbiš, Zlatko, and Ian Woodward. Cosmopolitanism: Uses of the Idea. Sage, 2013.

Suggested Citation

Acciari, M. (2017) ‘Film festivals as cosmopolitan assemblages: a case study in diasporic cocreation’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 14, pp. 111– 125. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.14.06.

Monia Acciari is a Lecturer in Film and Television History at De Montfort University. Her principal research interests lie in the areas of Film and Cultural studies. Her areas of research are: film festivals and the South Asian subcontinent; popular Hindi cinema ad ethnicity, transnational cinema and diasporic audience studies. Dr Acciari is the Associate Director of the Leicester Asian Film Festival, and Principal Investigator of the research and diasporic community engagement project “Building Audiences”. She is also one of the cofounders of the international research network Euro-Bollywood.