The Shore Line as Polyphony in Practice: A Case Study

Elizabeth Miller

As a documentary maker with experience in media advocacy I see media as a first step in a longer process of social engagement. I am as invested in the outreach stage of a project as I am in the production and what really matters to me is how an i-doc can be used and circulated to make a difference. For many documentary makers, the appeal of an i-doc is the nonhierarchical curation of people, place, environments and media forms. I see i-docs as a platform for polyphony in practice. By polyphony I mean the creative engagement of voices, authors, elements and forms towards a common objective. My goal in making The Shore Line (2017) was to use an i-doc to create a collaborative story of resilience and climate justice. I was drawn to the coast as a subject, as a metaphor and also a method—as a way to reach across borders and challenge narratives in addressing climate disasters. The surge of coastal tourism, the increased dumping of industrial waste, and the unsustainable growth of fossil fuels are threatening the very ecosystems that protect us from storms and sea level rise. Rather than dwell on disaster, I was inspired by Anna Tsing’s notion of collaborative survival and her provocative invitation to observe what survives in the midst of disaster.

Change at the shoreline can be sudden with storms that result in massive destruction, flooding, displacement and death. Changes also play out through what Rob Nixon calls “slow violence”, involving the gradual seeping of toxins into the water or the displacement of shoreline communities and cultures. Likewise, social change often comes in the form of what I call “slow resilience”,enacted through a deepening knowledge of coastal ecosystems and collaborative frameworks. Over three years and in collaboration with students and filmmakers from around the world, I curated a collection of forty-three video profiles of people taking actions over time, often in quiet but resourceful ways.

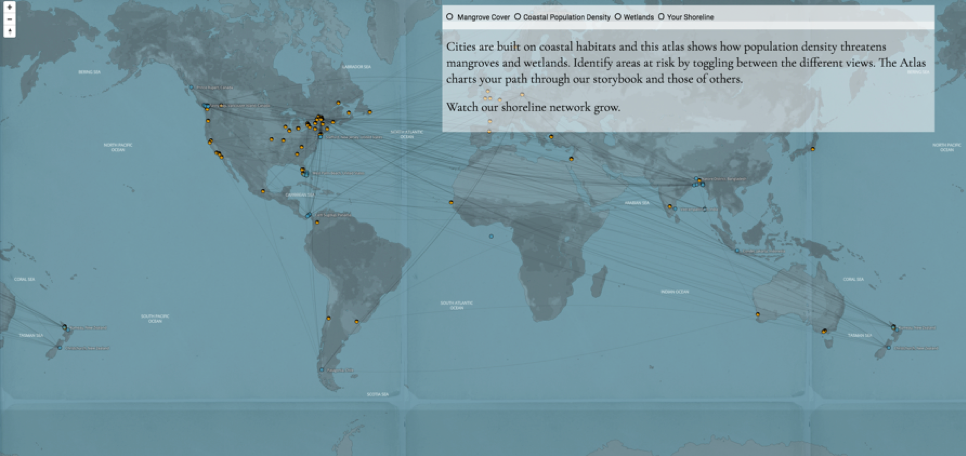

Figure 1 (above): The Shore Line involves students and filmmakers from nine countries. Original Design, Helios Design Labs. theshorelineproject.org.

Figure 2 (below, left): The Sagar Island’s Women’s Collective in India are cultivating agriculture alternatives in flooded fields in “Salt Resistant Seeds”. Still by Eva Brownstein. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?Country=India.

Figure 3 (below, right): Sustainable architect Mohammed Rezwan of Bangladesh showcases his floating education system and floating farms in “A Floating Future”. Still by Liz Miller. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?Country=Bangladesh.

Each short was developed with some degree of collaboration. For the segments from Norway, Indonesia and Chile I relied on participating directors to shoot the segments. In Carti Sugdup, an indigenous community in Panama, I trained a local youth group to cocreate the production. And when I was on location, I often worked with local journalists. The final project features individuals from nine countries including a sustainability architect in Bangladesh designing floating schools, an Indigenous organiser in Panama moving his community from a sinking island to the mainland, a science fiction writer from Canada writing resilience into storylines, and many more. [1]

Educators as a Target Audience

Over the last several years when I am at festivals, conferences or even faculty meetings I hear a familiar refrain: “Who exactly is the audience for interactives?” Many film festivals are still figuring out how to properly program i-docs so that they don’t end up in neglected corners, as sideshows to other main features. And while access might appear to be baked into an i-doc, attention is not a given for a project whose home is the Internet. A big challenge for i-docs is maintaining attention in a crowded mediasphere where viewers can click away if they are not immediately entertained or engaged. An interactive project like The Shore Line has several hours of material; yet, users spend an average of seven minutes on the site, which is a very unsatisfying viewing ratio. Many practitioners have been exploring a wide range of methods to get users to move beyond a cursory visit and dig deep into what is often a great deal of content.

As a professor, I use interactives as primary texts, so of course I have a bias, but I do believe that one of the crucial places where interactives can really make a difference is in the classroom. Since academic semesters run from ten to thirteen weeks, classrooms can offer an immersive experience, where students can engage with a project over time. Furthermore, the polyvocality of many interactives works well in a classroom where students are asked to consider comparative perspectives, frames of references, and situated experiences. A collaborative nonlinear form offers a welcome alternative to the exceptionalism of the single protagonist and puts diverse perspectives into conversation. As scholars Helen De Michiel and Patricia Zimmerman have suggested, interactives present an “open space” where iterations, communities and diverse forms of engagement can emerge. In developing The Shore Line, I wanted to make educators the target audience and see how engaging with them through the process would impact the development, the aesthetics and even my own perspective on advocacy, education and outreach strategies.

Figure 4 (top): The Shore Line crew collaborates with students from Carti Sugdup, Panama in “To the Mainland: Carti Sugdup’s Solution”. Still by Deborah Vanslet. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?Country=Panama.

Figure 5 (bottom): Youth educators in Panama explain the important of mangroves in “Protectors of the Mangroves”. Still by Liz Miller. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?Country=Panama.

I had a personal motivation for designing an i-doc for educators. I teach a course in media and the environment and one of the biggest issues students express is being overwhelmed by the scale of environmental destruction. Glenn Albrecht, a philosopher and professor of sustainability at Murdoch University in Perth, has coined the term “solastalgia” to describe the profound sadness we feel knowing that the landscapes that we love are under attack. Albrecht came up with the term as the coal industry in South-East Australia was turning the coastal city of Newcastle into the largest coal-exporting port in the world. People were writing to him in desperation as the landscape disappeared before them. I wanted to create a resource that spoke to my students’ concerns and that featured achievable actions. I wanted to curate a space where they and others could discuss how place, traditions, gender, race, age and economic circumstances inform local methods of resistance or resilience. The individuals profiled in The Shore Line draw on local knowledge and offer a wide range of responses to coastal challenges. I hoped that when situated in conversation with others the project would communicate a powerful force of change and inspire my students and others to discover their own forms of taking action.

Figure 6: Youth organiser Ta’Kaya Blaney emphasises the value of cultivating youth leadership and teaching land rights in “Youth Leaders of the Salish Nation”. Still by Liz Miller. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?Country=Canada.

Other Models of Engagement

I started the project by researching what was already happening with engagement. I first spoke to the directors and outreach coordinators of three high profile Canadian interactive projects including Here at Home, Fort McMoney and Highrise. [2] These conversations led to several key insights about how to ensure that an online documentary would not simply be lost in a sea of content. The first insight was about the critical role of partnerships in reaching a target audience. In this case, impact should not be conflated with exposure since getting a project to the right audience can be more effective than trying to reach everyone. The second method that these projects were developing was the forging of media partners, who were helpful in getting broad attention for a project. For example, Highrise collaborated with The New York Times and The Atlantic at different stages of the project to garner attention around issues related to urbanisation. Fort McMoney partnered with media in Canada, France and Germany to foster debate around petroleum. This model can be applied to smaller media outlets as well to reach more targeted audiences. A third and critical insight was the invaluable role of a guide. Using the name of “game masters”, “super players”, “matchers” and more, each director pointed to the need for a guide, someone to draw out the complexity of a project and to help generate interest. It is easy to miss out on key features in a crowded mediasphere so having a dedicated person to help users navigate the site and to seed debate is critical for an interactive to remain relevant for more than the average seven minutes.

In addition to speaking to i-doc directors, I also referred to case studies of long-format environmental documentaries that were made with the intention of shifting public perspectives and practices. Shirley Roburn in her thoughtful essay “Beyond Film Impact Assessment: Being Caribou Community Screenings as Activist Training Grounds” carefully analyses the long-term advocacy strategy of the film Being Caribou and deconstructs simplified notions of social engagement. Beautiful Solutionsis an elegant Internet resource companion to Naomi Klein’s feature documentary This Changes Everything that works well in the classroom. The film and extensive engagement campaign were accompanied by targeted outreach to schools and community groups. I was also curious to understand what artists and researchers from diverse disciplines were doing to make their work matter. Together with Steven High, an oral historian, and Edward Little, a theatre artist, we conducted over thirty interviews with artists and scholars who were invested in the social impact of their creative work. [3] Our main take-away was that there are few shortcuts in making cross-disciplinary projects matter. Social impact takes time and solid partnerships are an essential part of the process.

While I was learning a great deal from inspiring practitioners, I still felt that the classroom as a targeted site was lost in the quest for mass exposure. This is not to underestimate the impact of projects like Campusthe National Film Board’s five-star educational resource or the stellar educational guides that projects like Highrise have developed, but it just seemed to me that if teachers were somehow invited in as partners early on, there might be a way to advance the potential of an environmental i-doc in the classroom.

Figure 7: Elke Van Breeman with students at Beachcombers Academy in “Lessons on the Coast”. Still by Liz Miller. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?People=Educator. Strategies for Enacting Polyphonic PracticesTaking into consideration all the valuable insights I gleaned from i-doc directors and others, I developed six distinct strategies to build engagement with teachers. The first step was to form a small advisory group of teacher trainers working at different levels of education. [4] This small committed group accompanied us over three years and offered suggestions and consultations along the way. The second strategy was to feature inspiring educators in our short films. We developed profiles of educators from India, the US, and Canada who are helping their students connect to the environments around them and who are helping students initiate actions and campaigns. We also feature youth educators (ages thirteen to twenty-three) who with the support of mentors are holding workshops with adults, planting mangroves in sinking communities, and learning about laws and treaties in order to defend their land.

Figure 8: Sefali, a youth leader in the Sundarbans of India is planting 35,000 trees with her classmates in “Dreaming of Trees”.

Still by Eva Brownstein. theshorelineproject.org/#!/archive?People=Youth%20Leader.

The third strategy was to share our work in progress. Rather than waiting for a definitive launch we developed an interim website where we showcased the profiles as we developed them. This offered us a unique opportunity to foster a network amongst the very individuals we were profiling. For example, when we led a media workshop for youth in Panama, we shared our youth profiles from India and Norway. The Panamanian group was enthusiastic to see what other youth were doing, and as a result they saw their own efforts as part of a larger initiative. Our interim site was an instance of “in-reach”, a way to foster connections between and amongst our emergent network and the inspiring individuals we were meeting in each location. Finally, our interim site worked as a public sketch pad. It was an open platform where we could adapt, explore and begin to identify the emergent aesthetics, themes, and connections between each place and story. After we launched the official interactive Shore Line site we transformed our interim site into an educators’ exchange. Once again, our intention was to foster connections and share resources as our network of teachers and our engagement strategy evolved. For example, we have been conducting interviews with teachers who are practicing sustainability in their classrooms. We will feature these interviews as well as other curriculum resources in the educators’ exchange.

One of the challenges when creating an i-doc for social change is that every profile seems like an important opportunity to engage, but users and teachers are easily overwhelmed. Too much content can be ineffective. There is a tension between the desire to engage with many individuals and the need to have a resource that does not overwhelm users. Our fourth strategy, a series of curated guides, is one way that we tried to address the overwhelm issue. Our advisory committee explained that teachers spend only a few minutes reviewing a new resource and that we should keep them simple. Rather than develop these guides ourselves we wanted to build engagement with educators and experts through the process. I asked graduate students, environmental journalists, sustainability experts, and experienced teachers to author a one-to-three-page workshop guide that we would then feature on our site. Each invited author was given three-to-six films to watch and a template to work from. It was a perfect “pilot” activity to build outreach partners and to continue in our quest for shared authorship of the project. The initiative demonstrated that shared authorship can happen at any stage of a project and in several cases the development of a guide led to other endeavours including conference presentations and workshops. For example, a seasoned environmental journalist suggested that we lead a social media event modelled on a hackathon. We invited teachers of all levels to discuss social media in the classroom and spread the word about the project. It was a meaningful way to explore our social media strategy, to network, and to do outreach in the company of others.

The fifth strategy was to test the project with teachers at different levels. I began by using the project in both an undergraduate and a graduate course. For a graduate seminar on media and the environment, I had my students watch four short videos each week paired with articles we were reading. They were asked to write weekly responses on a web forum that we developed for the class. The best part of this exercise was the ritual of writing and the challenge of synthesising dense articles with the short videos. With my undergraduate production class, I sent eight video production teams to different shoreline sites around the island of Montreal as part of a place-based observational exercise. By visiting, observing, and documenting their own shoreline, the students had a more informed starting point for analysing the site and the challenges of other shoreline communities. Other professors at my university have also integrated the project into their classes and we cocreated a university gallery installation with student participation. Here we used the i-doc as a prompt to focus on a local shoreline issue. We plan to repeat the experience at other University galleries.

The project has been a useful prompt to reach across both disciplines and pedagogical levels. For example, my university is across the street from a high school that I had never entered. Today I know all the teachers at the high school who are working on sustainability. A few teachers have integrated The Shore Line and the solution-based pedagogy approach into their curriculum. One example is a woman who teaches art and architecture and is having her students redesign a resort impacted by hurricane Irma. She is using The Shore Line to get the students thinking about how culture, collaboration and sustainability are critical aspects in design and architecture.

It is no secret that designing a project that will work in classrooms from Bangladesh to Canada is an enormous challenge. Our sixth strategy was to ensure the project would reach across platforms and cultures. We have made numerous difficult decisions in an attempt to balance innovation with very real technological constraints. In teacher trainings throughout Montreal I am learning about the resources teachers need and some of the constraints that they face. I led a workshop for fifty teachers and the room I was given had a firewall so none of the videos were accessible. Luckily I found a workaround, but it was a reminder of the limitations with online initiative at schools. We took the project to our collaborating partners in the Guna Yala islands on a USB since they are not streaming media in the class. The reality is that every teacher has a different screen, a different platform, support system, and a different relationship to technology. And there is a lot more to figure out to make this interactive matter. I can already see how critical is to sit down with teachers, review the site together and explore how the project might support their priorities.

A Short Tour

Figure 9: Still of Interactive Atlas. Original Design by Helios Design Labs. theshorelineproject.org/#!/endpanel.

Curating polyphony is a design strategy as much as a careful curation of people and places. We designed three ways to navigate The Shore Line. The first is by using the chapters, that are meant to invoke the idea of a storybook or textbook. Each chapter opens with an original coastal soundscape. There are six chapters and up to seven videos per chapter displayed on a page. On the flip side of each video page, users can find a dynamic map with a sea-level slider, to explore what each community will look like with up to six meters of water. Each video is also connected to a strategy toolkit that has related videos, guiding questions, additional readings, and community-based activities. At the end of each chapter we have flood views. These are dystopic glimpses of what some of our densest cities might look like in the near future. The second way to navigate the site is through the database and this is designed with teachers in mind. Here users can access the stories through a range of keywords and categories including our strategy toolkits. The third way to navigate the site is through the Atlas. Here, users can access videos but can also toggle between data sets of coastal density, mangrove cover and wetlands to visualise how urban development and sea level rise are impacting ecosystems. In the Atlas area, we developed a visualisation, Your Shoreline, that traces each user’s path. The map is a dynamic visualisation of the emergent network of people using the site. In Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown suggests that emergence takes notice of the small actions and connections that become systems, patterns, ecosystems and more. We hoped that by mapping users’ paths we might visualise our own emergent network.

Entanglements

Figure 10: Still of Cable. Original Design by Helios Design Labs. theshorelineproject.org.

Does our medium match the message? While we reduced our carbon impact by relying on partners around the world, The Shore Line and my own practice as a documentary maker are fraught with entanglements. When most of us discuss impact, we are thinking largely of outreach but we talk less about the impact of our projects on our landscapes. I had wanted to tell the story of the hidden Internet infrastructures that we rely on to communicate stories like The Shore Line. Over ninety percent of international data is transmitted by cables at the bottom of the ocean. These big heavy submarine communications cables stretch from shore to shore, and are largely out of sight, out of mind, to most of my students. While we feature an Internet cable on our interface we never fully resolved how we might instigate a deeper reflexivity about the energy required to both produce and watch an interactive. I am still grappling with how I and other makers might communicate climate justice stories with a lighter footprint. Meanwhile, Glenn Albrecht is focusing on “soliphilia”, a concept he developed to encourage the love of and responsibility for our homes, bioregions and planet. Hopefully The Shore Line is one small part in a desperate need to foster soliphilia and the interconnections with each other and with the ecosystems we rely on.

Notes

[1] Their contributions may be viewed under the “People” section of The Shore Line’s database.

[2] For more on these conversations see Miller and Allor.

[3] The interviews we conducted are featured on the website Going Public and in our book Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice.

[4] Our three consultants were MJ Thompson, Michele Luchs, and Adriana de Oliveira.

References

1. Albrecht, Glenn, et al. “Solastalgia: The Distress Caused by Environmental Change.” Australasian Psychiatry, vol. 15, sup. 1, 2009, pp. S95–S98.

2. Beautiful Solutions. Edited by Eli Feghali, Rachel Plattus, and Elandria Williams, 2016, solutions.thischangeseverything.org. Accessed 5 Sept. 2018.

3. Being Caribou. Directed by Leanne Allison and Diana Wilson, produced by Tracy Friesen, National Film Board of Canada (NFB), 2005.

4. De Michiel, Helen, and Patricia Zimmerman. “Documentary as Open Space.” The Documentary Film Book, edited by Brian Winston, BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 366–75.

5. Fort McMoney.Directed by David Dufresne, National Film Board of Canada (NFB), 2013, fortmcmoney.com. Accessed 5 Sept. 2018.

6. Going Public. Directed by Elizabeth Miller, Steven High, and Edward Little, 2013. goingpublicproject.org. Accessed 5 Sept. 2018.

7. Here at Home. Directed Manfred Becker, Sarah Fortin, Darryl Nepinak, Louiselle Noel, and Lynne Stopkewich, National Film Board of Canada (NFB), 2013, www.nfb.ca/interactive/ here_at_home.

8. Highrise.Directed by Katerina Cizek, National Film Board of Canada (NFB), 2009–2014, highrise.nfb.ca. Accessed 5 Sept. 2018.

9. maree brown, adrienne. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. AK Press, 2017.

10. Miller, Elizabeth, dir. The Shore Line. 2017, www.theshorelineproject.org. Accessed 5 Sept. 2018.

11. Miller, Elizabeth, Edward Little, and Steven High. Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice. UBC Press, 2017.

12. Miller, Elizabeth, and Martin Allor. “Choreographies of Collaboration: Social Engagement in Interactive Documentaries.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 10, no. 1, 2016, pp. 53–70.13. Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard UP, 2013.

14. Roburn, Shirley. “Beyond Film Impact Assessment: Being Caribou Community Screenings as Activist Training Grounds.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 11, 2017, pp. 2520–39.

15. Smith, Daniel B. “Is There an Ecological Unconscious?” The New York Times Magazine. 27 Jan. 2010, www.nytimes.com/2010/01/31/magazine/31ecopsych-t.html.

16. This Changes Everything. Directed by Avi Lewis,Klein Lewis Productions and Louverture films, 2015.

17. Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton UP, 2016.

Suggested Citation

Miller, E. (2018) ‘The Shore Line as polyphony in practice: a case study’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 15, pp. 113-123. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.15.08.

Elizabeth Miller is a documentary maker and professor who uses collaboration and interactivity as a way to connect personal stories to larger timely social issues such as water privatisation, climate migration, refugee rights and gender violence. Miller is a Full Professor in Communications Studies at Concordia University in Montreal and has partnered with organisations including Witness and UNESCO. She has published several articles and book chapters on collaborative and interactive documentaries as social change interventions. Her recent coauthored book Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice features socially engaged practitioners exploring the political, aesthetic and performative dimensions of their work.