Beyond “Toolness”: Korsakow Documentary as a Methodology for Plurivocal Interventions in Complexity

Anna Wiehl

Korsakow is a method of arguing, a tool to make sense of the world. Watching Korsakow Films and even more making Korsakow Films is an exercise for the brain to see different connections, to find new patterns in things. (Thalhofer, “Korsakow”)

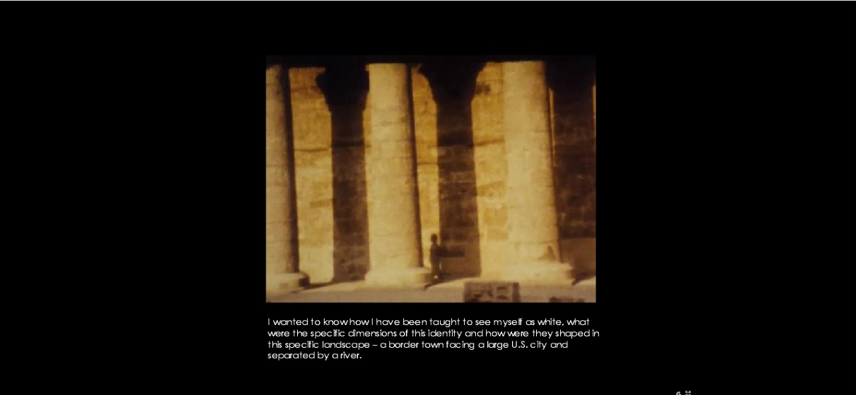

A small video frame on a black screen. A person is slowly passing a gigantic, probably ancient, Egyptian colonnade. The camera—most likely a 16mm film camera—follows the person marching from the right to the left behind the columns. From the distance, one can hear the atmospheric “white noise” captured by a microphone, presumably turned on accidentally. It is an unusual opening for an interactive documentary, especially if one considers that its title, Racing Home (Marianne McMahon and Phil Hoffman, 2014), implies that this factual is supposed to tackle issues of race and identity. Notwithstanding the puzzlement, this introductory sequence draws the user-interactor into the configuration, precisely due to its enigmatic power and the curiosity it arouses. The estrangement and bewilderment are certainly key to understanding an admittedly nonmainstream kind of interactive documentary—the so-called Korsakow documentary. Korsakow documentaries are generative, interactive computational database documentaries which follow the “logic” of nonlinearity: in contrast to most plurilinear (yet still plotted) documentaries, Korsakow relies on an asymmetry of keywords of its narrative units (in general, short video clips) and complex algorithms of probabilities which determine the narrative units that are presented to the user-interactor. As such, both the author and the user-interactor have to relinquish control to the Korsakow system.

The hypothesis underlying the issues discussed in this article is that new documentary practices potentially enable new forms of mediation which allow all interactors to experience complexity and deal with contingency in a world of polyvocality and in the form of multilayered configurations. [1] In the present exploration of the Korsakow documentary Racing Home, the epistemological and ontological status of these assemblages will be scrutinised. A central issue is the question of how far specific modes of editing in Korsakow affect the overall experience for both the authoring instances and the user-interactor. What role do polyvocality and algorithmic editing play? Furthermore, given Korsakow’s specific embracing of contingency and its probing of nonlinear narratives, the question arises whether configurations like Racing Home are more a methodology to explore complex matters of concern than a tool to present ready-at-hand answers.

Entering Racing Home

My work has always been process-based—seeking rather than settling on something; the finished project has always been less important than the moments of epiphany that happen while I am collecting, processing, and digesting the materials. (Phil Hoffman qtd. in Noble)

Originally, Racing Home was meant to be a linear documentary by the Canadian filmmaker Marian McMahon on identity, race and belonging. However, the project was never finished. In 1996, McMahon died of cancer and bequeathed to her partner Phil Hoffman an apartment full of 8 and 16mm footage—factual vignettes but also highly personal reflections, sound records and archival material she had collected. Apart from this media legacy, she also left boxes full of diaries and notes, maps, photographs, letters, notes, newspaper clippings and objects from vernacular culture which had become meaningful to her—either with regard to her research for the film or to her own identity-forming past. Thus, after McMahon’s death, Hoffman found himself confronted with a large array of diverse artefacts. Being a filmmaker himself, Phil made Marian’s project his own, and set out to edit her footage. However, he failed to force the material into the form of a linear documentary film, which—in his eyes—would neither pay due tribute to Marian’s intention when she was working on it in the 1990s nor justly depict his relationship with Marian and her filmic work. His search for a suitable form came to a conclusion when he discovered an alternative way of convening documentary experience: Korsakow. The suitability of Korsakow was mainly due to two features of these configurations. [2] The first is the possibility of not only juxtaposing objective and subjective perspectives and oscillating between them, but also of entangling them. The second is that Korsakow frees the author from the pressure to create a documentary narrative. Thus, Hoffman was able to come to terms with issues that seemed to evade linear narration such as the working of memory, commemoration and counter-narratives.

Let us return to the initial screen of Racing Home—the uncommented video displaying the figure passing the enormous columns of the Egyptian temple. This video frame, in which the short sequence is shown, does not fill the full screen, but runs in a small frame in the middle of an otherwise black screen. Below the screen, an excerpt from a text written by Marian McMahon appears in white letters—maybe an entry taken from her production notebook, or a passage from her personal diary, or a letter to a friend or to her partner Phil:

In this film, I begin with my own experience, my own ethnicity and background. In doing so, I return to my hometown, Windsor, Ontario, to see how this landscape, this location has worked to produce a “raced” identity. I was especially interested in examining how I was living this past. What if geography is wounded but equally a place we call home?

I wanted to know how I have been taught to see myself as white, what were the specific dimensions of this identity and how were they shaped in this specific landscape—a border town facing a large U.S. city and separated by a river. To get caught up in histories of which we are largely unaware is inevitable. Yet we have a historical responsibility—the past shapes us in ways that are still with us.

Figure 1 : Opening sequence of Racing Home (Marianne McMahon and Phil Hoffman, 2014). Screenshot.

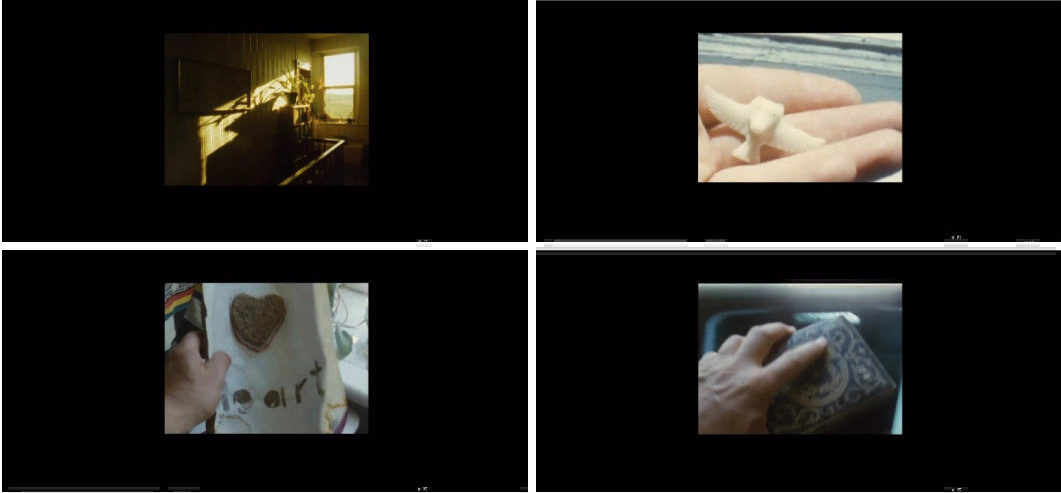

Towards the end of this opening sequence, a small, still thumbnail image appears on the right-hand side of the screen. A hyperlink offers the option to activate this frame, which then moves into the large frame, substituting the former clip. This sequence, filmed by a shaky handheld camera in a first-person perspective, presents a slightly untidy room: the perspective is that of a person—Phil’s, as one learns later—who explores a room in which the objects Marian bequeathed to him are kept. After a panning point-of-view shot, the still unsteady handheld camera sees some close-ups including a small figurine, earrings, a button and a timber box. As the protagonist—obviously Hofmann—picks these objects up, the narrating voice contextualises these actions.

Figures 2–4: Screenshots from the second clip of Racing Home.

Together with this second clip, a second voice comes into play—in fact, the first voice, which really speaks to the user-interactor—addressing her/him more or less directly. With reference to the words just seen as a white subtitle, it states:These words were written by Marian McMahon two years before her untimely passing away. As her partner of 13 years, I tried to finish Racing Home but was not able to complete the project, the story she had accumulated from the vast sea of sounds and images, relationships and ideas that I could not consolidate into a unified frame. 17 years later, through the advent of database filmmaking, I returned to her archive to discover its meanings.

In contrast to the rather enigmatic sequences, which the user-interactor encounters when digging deeper into the Korsakow documentary, this second video is fairly direct: it sets the mood and raises the four intertwined issues of Racing Home as a complex assemblage: firstly, Marian McMahon’s personally motivated consideration of her hometown’s racial past; secondly, her examination of family relations and questions of belonging; thirdly, Phil Hoffman’s relation to Marian and Marian’s filmic project; and, last but not least, Phil’s mourning in the form of “posthumous cinema” (a phrase coined by Monika Kin Gagnon in 2014) after the loss of his long-time partner.

When the clip ends, the frame in which the video was active becomes smaller and the three small thumbnail stills of potential following clips appear. Though the stills do not give away factual information of what the clip might present, they clearly show that the user-interactor is on the threshold of entering a complex interactive environment which interweaves material from many sources—adding up to a plurivocal chorus modulating on the theme of belonging and loss, race, history, memory and identity.

Figure 5: Screenshot from Racing Home displaying the variety of material gathered and entangled

within the Korsakow documentary.

The Korsakow System: Specificities of an Unruly Database Documentary

Korsakow is as much a philosophical intervention into the politics of “story” as it is a media software application for making database narratives, chiefly documentaries. (Soar, “Making” 168)

The proposition here is that there are three intertwined specificities in Racing Home. To start with the most obvious aspect—the heterogeneity of the audiovisual material and the nature of the single clips—one can state that, as the description of the first sequences has already shown, Korsakow documentaries often consist of short, linearly edited video clips, called SNUs—Smallest Narrative Units.This implies that a single SNU can be made up from more than one cut or dissolve, while the unity of the narrative structure comes from the interrelationship between the SNUs. The fact that a medium is made of SNUs and that these are to be regarded as undividable wholes (which form units of their own) is also known as the “modularity of a medium” (Manovich 27) or its “granularity” (Miles, “Matters” 117). These SNUs form the centre of a Korsakow documentary and build the stock of the interactive database. In the case of Racing Home, we are dealing with at least four different kinds of material which contribute to the plurivocality of the documentaries. There is the material Marian left, including archival footage from old newsreels, amateur family video, and material she and Phil shot on different occasions and in different places (in Ontario, but also in Egypt and Europe). This material reflects on questions of race, gender and belonging. Additionally, there is the material Hoffman shot after Marian’s death—which consists of self-reflexive, first-person considerations addressing the topic of time, death and mourning, but also the nature of artistic expression and the entanglement of autobiographic documentary which deals with the past. Thus, the user-interactor encounters a complex polyphony of different voices.This brings us to the second aspect which sets Korsakow apart from most other manifestations of emerging interactive documentary and brings it closer to a methodology than to a “representation of reality” (Nichols): the unruly use of “database logics” (Luers). To be retrieved from the database, each SNU has two sets of POCS (points of contact)—one set of in-POCs and one set of out-POCs. A POC is a set of keywords allocated to a SNU. These POCs can be metadata concerning the content of the SNU, but they can also hold information about formal properties, e.g. dominant colours, information on the camera angle etc. The two sets of data—the in- and out-POCs—determine the potential connections between clips. However, in contrast to usual keyword allocation in functional databases with unambiguous sets of keywords, in Korsakow one and the same keyword can be an in- and an out-POC. Thus, the user-interactor is confronted with an asymmetry of keywords. [3]

Figures 6–8: SNUs and POCsinKorsakow. Source: korsakow.tv.

From this follows the third specificity of Korsakow. In contrast to “orderly” determined and deterministic databases relying on a symmetry of in- and out-keywords, keywords in Korsakow are “fuzzy”, as any keyword, set of keywords, or parts of a set can be shared by more than one clip. Consequently, there exist many possible connections between the out-keywords of one SNU and the matching in-keywords from another SNU. Clips in Korsakow simultaneously have multiple destinations. At this point, contingency comes into play and Korsakow shifts from being a tool or a simple delivery platform for a documentary argument to a procedure or method to deal with material. Korsakow configurations rely on loose and ephemeral probabilities around how material can be linked. They are also based on more-or-less likely connections between clips which are not only obscured to the user-interactor but also to the author herself or himself due to the sheer combinatory complexity of rules. As such, Korsakow’s general default behaviour obstructs the linear sequencing of clips. The database here does not present itself as an organised collection of items optimised for fast retrieval of information—a feature that is most often used for the creation of educational or didactic database documentaries or interactive documentaries focusing on curatorial issues of data. Additionally, it does not expose a clear structured chain of cause-and-effect logics and does not allow for the creation of a strong narrative line to develop an argument within the documentary. Rather, the interpretation of database in Korsakow as combinatory engines brings forward a complex network of affective narratives which are explicitly not instructive or informational but which open a field of perspectives through a heterogeneous variety of plurivocal material. As such, most Korsakow documentaries evade linear conventions of storytelling with a clear dramaturgic arch characterised by a rising tension and an end. In the case of Racing Home, in this “formlessness” of form, content and structure of the assemblage are, again, deeply entangled. They are—like grieving and commemoration as well as the question of who we are, where we come from and where we are going to—questions that stay with us and to which there seldom is one definite and “true” answer.

Process of Editing in Interactive Networkedness: Three Modes of Montage in Korsakow

Korsakow is not a format to present video clips, Korsakow is more of a format in itself. (Thalhofer, “Korsakow”)

Korsakow quietly expands what video can do, and in turn what it then means. (Miles, “Materialism” 211)

As was just seen, one can state that at the heart of every Korsakow configuration lie SNUs, a collection of two sets of POCs (in-POCs and out-POCs) and the interface as a connection which allows the unfolding of interrelations between agents. These three elements are related to the ontology of the work—especially the three different forms of editing which bring Korsakow assemblages forward and which also reflect the “life cycle” of production: firstly, the (linear) editing of the SNUs which form the material of the experience; secondly, the adding of metadata to the SNUs—i.e. specifying sets of keywords which form the POCs and the determining lifespans of these POCs; and, thirdly, what one can call performative, procedural or “readerly” editing by the user-interactor—i.e. the realisation of one of many possible versions of an ephemeral, dynamic documentary “text”. Performative editing refers to the actual interactions of different agents always unfolding anew within the networked configuration and, thus, calls for a more holistic consideration of the assemblage—i.e. a transdisciplinary approach which considers the inherent dynamics of the Korsakow configuration. This third form of editing lies in the hand of the user-interactor: it consists in choosing one of the potentially following clips—most often without knowing what is coming next. Procedural or performative editing leads to the realisation of an ephemeral (textual) network—the actualisation of one path through the material, i.e. the actualisation of one possible narrative out of thousands.

The temporal dimension of the linearly edited clips and of their runtime determined by algorithmic editing becomes interwoven with the spatial dimension of interface design—the computational-driven arrangement of potentially following elements on the screen. Through this procedure, the hard videos of the SNUs become subject to “soft videography” (Miles, “Softvideography”). The distinction between the two are that where hard videos are edited linearly and each shot has a fixed position in the filmic “text”, the SNUs inform a complex network of videos in which the granularity of the filmic text and the various speaking voices are not fixed. In this sense, granularity and plurivocality become prerequisites to create multiple relations between SNUs, which in turn alters the way a work is structured to convey meaning and which forms the basis for performative editing by the user-interactor. As such, one and the same shot can take on different meanings—despite the fact that the shot itself remains unchanged. Hence, in Racing Home, processes of editing and meaning-making through editing lie as much in the hand of the user-interactor as they do in the hands of the author(s). Where the process of editing in documentary film can be considered as “closed”—the single shots have been arranged in a linear sequence—it is twice opened up in interactive configurations such as Korsakow. First (as is the case with many interactive environments), formerly determined fixed relations become flexible and the granularity of SNUs in the database is preserved. One clip can lead to various other clips—one documentary argument can be followed by several other aspects that are (more or less) closely related and which “make sense” in more or less obvious ways. Second, interactive documentary networks are often ephemeral realisations of possible plurivocalnetworked textures.

“Letting the Material Breathe”: Distributed Authorship in Korsakow

[T]o work successfully with Korsakow requires some surrendering of your agency to the procedural demands of the unit or system. Korsakow’s desire to engender multiple, loose, possible connections is a computational response that makes material the force that is already immanent in cinema to connect and establish relations between otherwise separate parts. (Miles, “Materialism” 219; emphasis added)

Where most narrative-driven or information-orientated interactive documentaries are plurilinear (but, often, still linear) Korsakow configurations are a radical probing into nonlinearity. The difference hereby is that plurilinearity still works on the premises of linearity: though there exists more than one possible path through the material stored in a database, these paths are still prescribed by an author who “plots the database” (Luers). Such plotted databases, which according to Gaudenzi function similarly to hypertext, bear similarities to the structure of “choose your own adventure” books. The overall experience in Korsakow, in contrast, is determined bycontingency and a distribution of authorship and agency within a networked configuration. This is due to the hypercomplexity of algorithmic editing, which evades absolute authorial control and, furthermore, to opaque key-wording that blocks search-driven information retrieval and affords associative floating instead. These two factors lead to what can be described as the major difference between linear editing in film and algorithmic editing in computational documentary for interactive environments: whereas in the former only documentary makers function as authors, in interactive environments authorship is shared with or distributed between several agents—including “primary authors”, user-interactors, and the algorithms underlying the interactive configuration. In Korsakow, the role of the agent, who “traditionally” would be regarded as the documentary author, changes. Possibly matching SNUs are only partially visible and “trackable” for the Korsakow author: though s/he knows the single keyword strings s/he has allocated to the clips, s/he loses the total overview over the multiple combinations of possible connections. Thus, by distributing sets of keywords to SNUs and by opening up the possibilities of potentially following clips, the author no longer determines the one and only specific connection between clips. Instead, s/he opens a “field of possible relations” (Miles, “Interactive” 70). The database affords multiple paths realised both programmatically through key-wording and through the user-interactor’s procedural exploration of the database—respectively, the combination of all three.

Moreover, keywords in Korsakow are not “informational” in the sense that they summarise the actual “gist” of the SNUs. Rather they are associative, building looselyon thematic and, even more, visual, formal or poetic parameters. They work on the basis of potential contiguities, not only coherent (narrative) continuity. Hence, instead of dethroning the author, Korsakow rather frees the author from the obligation to control and to prescribe all possible narrative branches. S/he no longer has to deliberately construct paths, present material in one (pluri)linear form. In this context Soar speaks of “an extraordinary degree of creative latitude in terms of storytelling, a latitude that database filmmakers have only just begun to explore through their ‘algorithmic editing’” (“Making” 163). In this regard, one can state that a major novelty of database documentary is the fact that it defies the necessity to create master narratives.

As delineated above, it is this feature that unburdened Hoffman from the pressure of arranging his (respectively, McMahon’s) material into one linear sequence or two, three or four possible paths through the audiovisual legacy. Instead, he was able “to let the material breathe” (Weinbren 71)—an important factor particularly, although not exclusively, in this specific configuration with regard to the heterogeneity of the material and the plurality of documentary voices which can be found in Racing Home. This brings us to the question of the epistemology of Korsakow configurations, the truth claims made and the voice of the documentary author. In this context, it is important to remark that, despite pluri- or even nonlinearity, documentary authors are neitherdeprived of the power to make an argument nor are they giving up their voice. Firstly, certain points can be made by the linear editing of the SNUs and, secondly, the author can design more or less probable paths through deliberate keywording or “snuifying”. However, with regard to the role of the author, a further aspect is essential in Korsakow with its complex networked nonlinearity: the author can procedurally explore material in a mode that differs from thinking in linear chains of cause and effect: s/he can create “clouds” (Miles, “Materialism” 214) of possible connections and by testing the configuration, s/he can discover “truths” that have been hidden to her/him in the material so far. The configuration becomes a kind of laboratory to think through digital media. With regard to concepts of (interactive) storytelling, memory and commemoration, of perception and cognition as well as the fathoming of existential topics like death, this moves Korsakow configurations closer to the logics of artistic research. It also affords the author a potentially even moredifferentiated voice than is the case with straightforward documentary configuration or documentary film of the expository mode.

In their editors’ introduction to New Documentary Ecologies Kate Nash, Craig Hight and Catherine Summerhayes argue that interactive documentary calls for “a re-examination of documentary theory itself in the light of an expanded ‘realm of the real’ and, in the process, to engage critically with the claim made on behalf of emerging media technologies [as] new tools changing documentary production” and audience engagement (2) This “re-examination of documentary theory itself” and its place within the study of interactive documentary is certainly key to understandsuch complex configurations (2). However, referring to this statement, one remark should be made regarding the role of digital media as authoring “tools” which implies a specific functionality—or, rather, open spaces for experiments as shown. In this sense, Korsakow as an admittedly extreme but nonetheless paradigmatic case of complex interactive documentary configurations presents features of “toolness” (Miles, “Matters” 10)—not merely in the sense of editing software, but rather in the sense of a “tool for thought” (Rheingold 1) for the documentary author (and, as will be shown, for the user-interactor too)—being rather a methodology of working with and thinking through audiovisual material in interactive configurations than simply presenting an editing device or delivery platform. “Toolness” in Korsakow goes beyond a functional dimension of merely being an editing software. Rather, it can be seen as a “tool for thought” for the documentary authors as well as for the user-interactor. Consequently, it qualifies as a methodology of working with and thinking through audiovisual material in interactive configurations rather than simply providing an editing device or delivery platform.

The Multiplied “I” in Interactive First-Person Documentary and the Transformative Potential of Subjectivity

To make sense in and of Korsakow, for making and viewing, it needs to be recognised, deeply and seriously as a unit, system, and actor network. We are actants within this system, but never its centre or origin. For documentary this proposes a reading and making of the world that is not pre-determined nor fully controllable, for maker, reader, narrator, or the work. (Miles, “Materialism” 219)

Despite the still widespread assumption that first-person films are myopic, ego-driven, navel-gazing works, the “cinema of me” is in fact rather a “cinema of we” (Lebow 1). Though the term “first-person cinema” implies an autobiographical perspective, first-person documentary does not necessarily need to be a self-portrait. Rather, the “I” of the author most often only serves as a point of departure to explore someone or something else—be it a single person, a community, a nation—or something more abstract, like a complex concept such as the notions of “home” and “belonging”. Hence, one can say that first-person documentary is foremost about a specific stance the documentary author takes towards the documentary subject—i.e. her/his positioning and the acknowledgement of an articulated subjectivity of positioning. In this sense, almost all the remarks Lebow makes on linear first-person film also apply to interactive documentary configurations: first-person documentary may be “poetic, political, prophetic or absurd”, “autobiographical in full, or only implicitly and in part”, or it may “take the form of self-portrait, or indeed, a portrait of another” (Lebow 1; emphasis in the original). [4] These remarks, I would argue, apply even more so to interactive configurations, as they feature not only as either/or options but also, due to the plurivocality of interactive documentary, can be realised simultaneously.

In interactive documentary, the always already implied “You” of the first person “I” of the documentary author resonates through the voice and direct address of the user-interactor: “‘You’ is called upon to participate and share the enunciator’s reflections”—and this “you” “is not a generic audience, but an embodied spectator” (Rascaroli, “Essay Film” 35). Additionally, Racing Home displays two of the major specificities Laura Rascaroli identifies with regard to the (first-person) essay film, its reflectivity and subjectivity:

an essay is the expression of a personal, critical reflection on a problem or set of problems. Such reflection does not propose itself as anonymous or collective, but as originating from a single authorial voice […] This authorial voice approaches the subject matter not in order to present a factual report (the field of traditional documentary), but to offer an in-depth, personal, and thought-provoking reflection (“Essay Film” 35).

Often, the cinematic author (in this case both Marianne McMahon and Phil Hofmann) create enunciators who are very close to their own personality as “extra-textual author” (Rascaroli, “Essay Film” 35). Moreover, according to Rascaroli, the documentary essay becomes a “meeting point between intellect and emotion” (“Essay Film” 28)—and with regard to the procedural, generative nature of Korsakow assemblages, one can add that, like the essay, Korsakow documentary “incorporates in the text the act itself of reasoning” (“Essay Film” 26). At this point, a second key figure in the making of meaning through interactive documentary assemblages comes into play: the user-interactor, who not only brings in her/his personal interpretation and reading of perspectives offered by the author but also actively contributes to the emergence of ephemeral documentary texts. This stance towards matters of concern is already implied in literary and cinematic essayistic forms, but is even more prominent in interactive assemblages. In this regard, Rascaroli stresses that “rather than answering all the questions that it raises, and delivering a complete, closed argument, the essay’s rhetoric is such that it opens up problems, and interrogates the spectator; instead of guiding her through emotional and intellectual response, the essay urges her to engage individually with the film, and reflect on the same subject matter the author is musing about. This structure accounts for the ‘openness’ of the essay film” (“Essay Film” 35). Author and reader/audience/user-interactor enter into a sort of dialogue: “each spectator, as an individual and not as a member of an anonymous, collective audience, is called upon to engage in a dialogical relationship with the enunciator, to become active, intellectually and emotionally, and interact with the text” (Rascaroli, “Essay Film” 36).

If one goes back to the very first clip of Racing Home and takes a close look at the sub-titles which are faded in, one of the main themes of Racing Home is already set out in the linear material: the interwoven nature of personal and collective story and history—of the “I” and the “we”. McMahon emphasises that she takes her own person as a starting point for her essayistic documentary project:

In this film, I begin with my own experience, my own ethnicity and background. In doing so, I return to my hometown, Windsor, Ontario, to see how this landscape, this location has worked to produce a ‘raced’ identity. I was especially interested in examining how I was living this past. (Emphasis added)

From this personal experience, she moves on to a more general level of dealing with our past as a collective—the “histories of which we are largely unaware” and which we are caught in. Still, she claims that “we have a historical responsibility—the past shapes us in ways that are still with us” (emphasis added). The “I” speaking here already implies a sort of “we”—a collective—as well as a dialogue with a “you” which comes into play in the interval between clips. As such, the implicit dialogue goes beyond the single, linearly edited SNU. A response of the user-interactor is inspired—a cognitive and emotional response, based on self-reflexive introspection, as well as a physical re-action—i.e. activating the next SNU on the basis of what the user-interactor has just experienced. As such, in the interactive configuration, the transformative potential of first-person documentary film—its potential “to excavate different conceptions of the self; to imagine multiple and even competing models of subjectivity itself” (Lebow 3)—gains momentum.

Most obviously, the multiplication of selves sets off when Hoffman adds his perspective on this issue of subjectivity, individual identity and collective identification. In this regard, Hoffman speaks of “polyphonic recitations”, evoking a “multiplicity in the telling of stories through the entanglement of personal memory and history” (Hoffman qtd. in Varga). The Canadian filmmaker sees his works as “experimental documentaries that [are] still personal but [take] into account—more fully—for other lives and various perspectives” (Hoffman qtd. in Noble). In fact, continuing the chain of thought McMahon had already started laying out in the fragments of her film, Racing Home embraces plurivocality in its full dimension if we only think of the heterogeneity of the material remediated, e.g. archival footage from different historical eras.

The multiplication of perspectives goes hand in hand with a multiplication of aims and the fact that we are dealing here with at least two intertwined topics: McMahon’s original project about her own “raced identity” and Hoffman’s relation with his partner and her filmic legacy. This affects how identity politics, the politics of documentary making and the making of history are approached; it affects personal concepts of dealing with time, the past and the passing away of beloved people; and it affects the nature of relations and relatedness. The first issue is most prominent in Marianne McMahon’s collection of material—the footage she recorded together with her partner and the archival material she retrieved from her hometown. History in the sense of “official history” (e.g. in form of the newsreel material from the 1940s) and personal, private, histories (e.g. in form of the family videos) are brought into new contextual relations through spatial montage in Korsakow.

The argument that there are no stable realities and that traditional moralities are arbitrary—the idea that concepts of history, race and self call for constant negotiation and renegotiation, contextualisation and recontextualisation—is not only rationally put forward by an authoritative voice; it is rendered experiential. As such, the cognitive and emotional commitment in subjective interactive documentary configurations encourages an ethically aware engagement with images and collective imaginations by the user-interactor who becomes involved in more than only interpretative activity. S/he has to actively take a position in the assemblage and recontextualise information; and s/he has to respond to them by aligning them within her/his frameworks of world-making and reflection. As numerous visual research and documentary theorists argue, this is central to making ethical decisions—not only within the interactive configuration but also in “real life” (Coover 210; cf. also Renov).

With this documentary assemblage, Hoffman creates an open space for reflection and continuous self-introspection. Instead of a singular line of cause and effect, he intentionally plays with plurivocality, contrast and contradictions; and he dares to pose Marianne’s questions concerning belonging, race and history anew. In this course, he refuses to present a closed story with a clear beginning, middle and end—a solution to a problem. Rather, he invites a thinking through of issues via the remediated audiovisual material. As such, again, Korsakow in its nonlinear nature and realisation of distributed authorship emulates our experience of the world, sense-making within this world and the working of our mind and memory.

Subsequently, despite their subjectivity, both major topics—the collective historical burden and the personal dealing with one’s past, the passing of time and mourning—call for dialogue as they cannot be coped with solitarily. Paradoxically, subjectivity links back to one of the primary functions of documentary rhetoric: the idea of stimulating some sort of dialogue between documentary agents and, via this virtual interaction, to initiate a kind of transformation—both in the individual and in society “at large”. Hence, a highly subjective configuration like Racing Home does not simply debunk “documentary’s claim to objectivity. In the very awkward simultaneity of being subject in and subject of,it actually unsettles the dualism of the objective/subjective divide, rendering it inoperative” (Lebow 5; emphasis in the original); and this, in interactive environments, does not only hold for the author but also and to the same extent for the user-interactor. At this point, finally, one can say that two threads that have been analysed so far—the issue of (distributed) authorship in Korsakow and the issue of user experience—are entwined: the always implied subjectivity of any configuration is laid open and becomes decisive for the experience.

More than a Tool, More than a Platform: Korsakow as Methodology for Plurivocal Interventions

Korsakow’s technological and aesthetic footprint is an alternative site for interactive documentary practice as authoring is a series of intuitive and more or less directed improvisations which have the tenor of “what if?”, or “what happens when?” and “I think I’ll try this instead”. (Miles, “Materialism” 217)

Korsakow presents a complex configuration for interactive storytelling that enables the creation of nonlinear plurivocal documentary configurations. In this regard, Korsakow is more than just a platform or a programme, more than a tool to promote a special purpose and to distribute material; rather it presents a media ecology which affords practices or methods to approach complex matters. Korsakow documentaries disrupt the often morally biased didacticism that has been dominant in many variations of documentary. The disruptive momentum, the interventions that are enabled on and within the material have at least the potential to open horizons for documentary practices.

As we have seen, the most outstanding features in Racing Home (and this goes for most Korsakow documentaries) are first of all the heterogeneity of material and the plurivocality of more or less subjective perspectives and voices as well as the interrelated levels of the “micro-narratives” told in the single video clips. This feature has been discussed in terms of filmic sequential editing and temporal montage, founding the argument on documentary theory. Secondly, there is the unconventional interpretation of “database logics” (Luers) in Korsakow with its multi-directional, double-barrelled, not clearly determined sets of keywords—a feature which has been dealt with as “algorithmic editing”; and, as third feature, we find a radical subversion of concepts of (interactive) storytelling, probing into pluri- and nonlinearity in a complex networked associative web of micronarratives.

In Korsakow, authorship is shared between the interrelated agents. As has been seen, in Korsakow, both the “I” of the author losing control over the “more-than-plurilinear” narrative and the “I” of the tentatively probing user-interactor are joined by a third authoring instance: the Korsakow system as one of the agents in a complex network. All three interactants—primary author, user-interactor and Korsakow system with the database of audiovisual material and algorithms—become engaged in a dynamic configuration in which they concede control to each other. The user-interactor concedes control due to the opaque linking in Korsakow which allows only to hint at where her/his choice might take her/him. The author concedes control to the user-interactor whose actions bring the database into life when s/he procedurally creates an ephemeral text (i.e. by performative editing). S/he also concedes control to the system, as s/he cannot fully control the large number of virtual options and loses the track due to the amount of potential paths one can take when entering the assemblage.

In this sense, Korsakow self-reflexively emphasises its own digital nature, challenges the issue of documentary objectivity, subjectivity, of representation and the inevitable constructiveness of mediatisation and invites new constellations of documentary agents. These specificities of the ontology and the epistemology of digital documentary configurations are key to understand and appreciate Korsakow: the fact that formal processes of creating the configuration are united with the user-interactor’s awareness that s/he is engaging in an interactive assemblage is not minimised but rather expanded. Thus, Korsakow is certainly not a tool for enabling informational, didactic interactive documentaries. Rather, it is a system that allows generative, associative patterns to emerge amongst its parts while the work is being authored and “played”. The dynamics of the ephemerally unfolding experience enables and favours the performative momentum instead of the representational. Like the author, the user-interactor is enabled to tentatively explore material. Again, Korsakow can be regarded as an experimental space for thinking through audiovisual material. Procedural editing is potentially accompanied by a reconsideration of the structures and practices of perception, memory, cognition and emotional engagement. Therefore, configurations like Racing Home are not only highly poetic in their networked nature but they are also highly self-reflexive, inspiring the user-interactor to ask further questions rather than presenting her/him with ready answers. In this regard, the plurivocal complexity of Korsakow assemblages theoretically affords experiences both challenging and rewarding, as it provides multiple affective and cognitive ways to respond to the material.

Notes

[1] In what follows, the terms “assemblage” (as coined by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, extended by Manuel DeLanda, and used in Jennifer Slack and Wise MacGragor’s articulation theory), “configuration” and “network” (as used by Bruno Latour and John Law to delineate not only technological setting but also techno-cultural and socio-political interdependencies) will be employed to describe complex hybrid, human and nonhuman, interrelational and fluid relations. See also Callon et al.; Slack and MacGragor.

[2] In what follows, I will speak of Korsakow as configurations in order to avoid a misconception of Korsakow as either merely a software (i.e. a “tool”) or a media artefact. Rather, I suggest that Korsakow projects are media environments which afford different experiences. The spectrum of Korsakow documentaries ranges in this regard from highly personal configurations, such as Racing Home or Small World (Florian Thalhofer, 1997), to configurations that convene a feeling of a concrete place, like Planet Galata (Thalhofer, 2010) and Ceci n’est pas Embre (Matt Soar, 2010), to generative database documentaries which tackle complex issues such as death—as, for instance, The End: Death in Seven Colours (David Clark, 2015).

[3] This means that one and the same keyword can be both in- and out-POC. Hence, the configuration plays with ambiguity and contingencies and renders a targeted search by keywords (as is usually employed in functional databases) impossible.

[4] Ersan Ocak’s thoughts on interactive essay film go in a similar direction when he discusses nonlinearity in documentary storytelling through “database” structures. In this context, he dissects how documentary authors think and design differently from linear filmmaking when they work on essayistic database projects and how paradigm shifts lead to new forms of user-interactor experience. Hence, in the context of interactive essay film, the notion of the database gains significance in a more cultural sense. See also Rascaroli (“Essay Film”; Personal Camera) on the essay film.

References

1. Aston, Judith. “Interactive Documentary: What Does It Mean and Why Does It Matter.” i-docs.org, 2016, i-docs.org/2016/03/27/interactive-documentary-what-does-it-mean-and-why-does-it-matter/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2018.

2. Callon, Michel, John Law, and Arie Rip. Mapping the Dynamics of Science and Technology: Sociology of Science in the Real World. Macmillan, 1998.

3. Clark, David. The End: Death in Seven Colours. 2015, theend7.net. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

4. Coover, Roderick. “Visual Research and the New Documentary.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol.6, no. 2, 2012, pp. 203–14.

5. DeLanda, Manuel. “Deleuze and the Open-Ended Becoming of the World.” Keynote. Chaos/Control: Complexity Conference, Bielefeld University, Germany, 27 June 1998. www.cddc.vt.edu/host/delanda/pages/becoming.htm. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

6. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi, Continuum, 2011.

7. Fox, Broderick. Documentary Media: History, Theory, Practice. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2017.

8. Gaudenzi, Sandra. The Living Documentary: From Representing Reality to Co-creating Reality in Digital Interactive Documentary. PhD thesis, 2012, research.gold.ac.uk/7997/1/ Cultural_thesis_Gaudenzi.pdf. Accessed 9 Sept. 2018.

9. Hoffman, Philip, director. Racing Home. 2014. racinghome.ca/film3/#/?snu=2596. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

10. Kin Gagnon, Monika. “Posthumous Cinema and Creative Archiving: Charles Gagnon’s R69 and Joyce Wieland’s Wendy and Joyce.” Cinephemera: Archives, Ephemeral Cinema, and New Screen Histories in Canada, edited by Zoe Druick and Gerda Cammaer, MQUP, 2014, pp. 137–58.

11. Latour, Bruno. “Technology Is Society Made Durable.” The Sociological Review, vol. 38, no. S1, 1990, pp. 103–31.

12. Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Princeton UP, 1986.

13. Law, John. “After ANT: Complexity, Naming and Topology.” The Sociological Review, vol. 47 no. 1 (suppl.), 1999, pp. 1–14.

14. Lebow, Alisa. “Introduction.” The Cinema of Me: The Self and Subjectivity in First Person Documentary, edited by Alisa Lebow, Wallflower Press, 2012, pp. 1–14.

15. Luers, William. “Plotting the Database.” Database – Narrative – Archive: Seven Interactive Essays on Digital Nonlinear Storytelling, edited by Matt Soar and Monika Gagnon, 2014, dnaanthology.com/anvc/dna/plotting-the-database. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

16. Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2001.

17. Miles, Adrian. “Interactive Documentary and Affective Ecologies.” New Documentary Ecologies: Emerging Platforms, Practices and Discourses, edited by Kate Nash, Craig Hight, and Catherine Summerhayes, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 67–82.

18. ---. “Materialism and Interactive Documentary: Sketch Notes.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 8, no. 3, 2014, pp. 205–20.

19. ---. “Softvideography: Digital Video as Postliterate Practice.” Small Tech: The Culture of Digital Tools, edited by Byron Hawk, David Rieder, and Ollie Oviedo, U of Minnesota P, 2008, pp. 10–21.

20. Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. MIT Press, 1998.

21. Nash, Kate, Craig Hight, and Catherine Summerhayes, editors. New Documentary Ecologies: Emerging Platforms, Practices and Discourses, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

22. ---. “Introduction: New Documentary Ecologies.” Nash, Hight, and Summerhayes, pp. 1–10.

23. Nichols, Bill. Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Indiana UP, 1991.

24. Noble, Jem. “As the Mind Tracks Shape… As the Mind Recalls Sound…” Luma, vol. 2, no. 7, Winter 2017, lumaquarterly.com/issues/volume-two/007-winter/as-the-mind-tracks-shape-as-the-mind-recalls-sound.25. Ocak, Ersan. “Rethinking Interactivity in Interactive Documentaries Through the Play Element.” The Aesthetics of Documentary Interactivity, Pamphlet, edited by Adrian Miles, vogmae.net.au/works/2015/pamphlet.pdf, pp. 16–25. Accessed 22 Sept. 2018.

26. Rascaroli, Laura. “The Essay Film: Problems, Definitions, Textual Commitments.” Framework, vol. 49, no. 2, 2008, pp. 24–47.

27. ---. The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film. Wallflower Press, 2009.

28. Renov, Michael. The Subject of Documentary. U of Minnesota P, 2004.

29. Rheingold, Howard. Tools for Thought. The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology. MIT Press, 2000.

30. Slack, Jennifer, and Wise MacGragor. “Cultural Studies and Communication Technology.” Handbook of New Media, edited by Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia Livingstone, Sage, 2006, pp. 141–62.

31. Soar, Matt, director. Ceci n’est pas Embres. 2010. embres.ca/filmE. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

32. ---. “Making (with) the Korsakow System: Database Documentaries as Articulation and Assemblage.” Nash, Hight, and Summerhayes, pp. 154–73.

33. Thalhofer, Florian. “Korsakow Film.” Korsakow Institut. 2017. korsakow.tv/formats/ korsakow-film. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

34. ---, director. Planet Galata. 2010. planetgalata.com. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

35. ---, director. Small World. 1997. korsakow.tv/projects/small-world-1997. Accessed 3 Mar. 2018.

36. Varga, Darrell. “In/Between Spaces.” philiphoffman.ca. 5 Oct. 2014. philiphoffman.ca/ inbetween-spaces.

37. Weinbren, Graham. “Ocean, Database, Recut.” Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow, edited by Viktorija Vesna, U of Minnesota P, 2007, pp. 61–85.

Suggested Citation

Wiehl, A. (2018) ‘Beyond “toolness”: Korsakow documentary as a methodology for plurivocal interventions in complexity’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 15, pp. 33-48. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.15.03.

Anna Wiehl has been a lecturer and research assistant at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, and a research fellow at the Digital Cultures Research Centre, University of the West of England, Bristol. Her transdisciplinary research focuses on digital media cultures and documentary practices. In 2010, she received her PhD in the international programme Cultural Encounters, University of Bayreuth.Apart from her academic career, she has been working for ARTE andthe German public broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk, among others. Currently, she is leading a research project on interactive documentary and finishing her habilitation work The “New” Documentary Nexus: Networked/Networking in Interactive Assemblages.