Polyphony in Practice: An Interview with Sharon Daniel

Sharon Daniel, Judith Aston, and Stefano Odorico

Media artist Sharon Daniel has been involved with the i-Docs community since its inception—having presented her online documentaries and works in progress at all five i-Docs symposia that have taken place since 2011. We consider her to be a central and inspirational figure within this community, for whom the concepts of polyphony and heteroglossia are key to her ongoing practice. Here we build on her own previous references to these terms, in order to explore with her in more depth how polyphony and heteroglossia play out through her work. We also ask how and why she sees this approach to “cultural democracy” as an ever-more-urgent form of activism and intervention.

ASTON: Could you start by describing how you position yourself as a media artist? What is it about the i-Docs community that appeals to you as a forum through which to present and discuss your work?

DANIEL: When I heard about the first i-Docs conference I was thrilled. My work didn’t really fit into the digital arts world (because my focus is on social justice, not technological innovation as such). It also didn’t fit into the documentary film world (because my work does not emerge out of cinema and it is not storytelling). So, after creating interactive interfaces to online audiovisual archives (that I had come to think of as interactive documentaries) in a kind of disciplinary isolation over a period of about ten years, I was eager to find a community of other makers and theorists committed to new forms of (and new ethics in) documentary practice. I-Docs has helped to create that kind of intellectual community.

I think of my work as documentary art and political activism. I align my approach with the Rancierian definition of “the political”––for Rancière, what defines “politics” is a particular kind of speech situation––when those who are excluded from the political order, or included in only a subordinate way, stand up and speak for themselves. In my practice, I attempt to create this kind of speech situation. In 2000, I volunteered at a local needle exchange and started interviewing homeless injection drug users. As a result of that encounter, I committed my practice to challenging structural inequality and state violence in the context of the criminal legal system. For the marginalised populations that I have coauthored with, like incarcerated women and injection drug users, speaking both from primary experience (as an individual with a uniquely particular perspective) and as part of a “class” of shared experience constitutes a political act. I have always believed that, as feminist author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says, “it takes more than one story”—and, I would add, it takes more than one form of production, representation and circulation—to address the consequences and root causes of injustice.

Any adequate statement on the contemporary socio-political condition requires a polyphonic approach—a plenitude of voices speaking directly from a multitude of contexts about their own circumstances.

Figures 1–4: Public Secrets (publicsecret.net). 2007. Screenshots.

ODORICO: Could you expand on this and say why contemporary technologies within documentary practice are of particular interest in and relevance to your work? How much have you brought pre-existing practice to these technologies and in what ways have they influenced your practice?

DANIEL: The most powerful and relevant contemporary technologies for my practice are the database, the web browser, and http (hypertext transfer protocol)—together these three technologies allow users to access the content of a database through a web browser. Building on that possibility, which is now taken for granted, I have been able to use a variety of media to create database-driven, interactive interfaces that bring the voices of multiple coauthors together to speak to the specific conditions of structural inequality they face.

The affordances of the database are relationality, lack of hierarchy and expansive capacity. The database provides the opportunity to design data architecture(s) that can contain large collections of subjective (qualitative) data—collections that, in a database, can be structured around the multiple meanings within the data. The database allows me to structure the data and the user’s access to it around an argument. The database is an armature on which I can shape an interface that allows a viewer/user to navigate through the multiple meanings of the data and interpret how the individual data objects combine to make an argument.

Long before it became possible for me to work with databases and online interfaces my work involved participation and interactivity. I started out developing interactive installations using video, sound and kinetic apparatuses powered by electrical relays and switches. These works were not documentary in nature, but they were early steps in the evolution of a body of work that engages audiences and coauthors through various forms of technologically mediated participation. In the late 1990s, I started using the internet as a platform for the design of what I thought of as collaborative systems—and, eventually, participatory media projects in which participant communities without access to media and information technologies could create their own self-representations online. Initially, I didn’t see this as a form of documentary practice, but that changed after I started working with populations, like incarcerated women and injection drug users, who, given their circumstances, were unable to engage in that sort of hands-on participatory media approach. That is when I turned to the interview.

Figures 5–8: Blood Sugar (bloodandsugar.net). 2010. Screenshots.

ASTON: You have mentioned Mikhail Bakhtin’s concepts of polyphony and heteroglossia fleetingly in the past. Could you expand on what these terms mean to you and how they relate to your work, particularly in relation to what you have previously said about autopoetic systems?

DANIEL: Before I learned of Bakhtin’s use of the term “polyphony” to theorise multivocality and heteroglossia in the novel, I understood polyphony from the “inside”—from singing in vocal ensembles performing medieval and Renaissance music while I was in college. My undergraduate degree is in music, specifically vocal performance. So, I came to Bakhtin with this embodied understanding of the polyphonic that was physical, auditory and visual as well as intellectual. Polyphonic vocal music from the late medieval and early Renaissance periods generally consists of multiple independent melodies that rhythmically and harmonically converge and diverge to develop complex musical textures and architectures of theme and variation, point against point in vertical (melodic/harmonic) and horizontal (temporal) relation. As a performer, it is something like being in a conversation with a number of people where everyone is interrupting each other, talking over each other and sometimes speaking at once—but with a kind of script. In other words, it is collaborative and immersive.

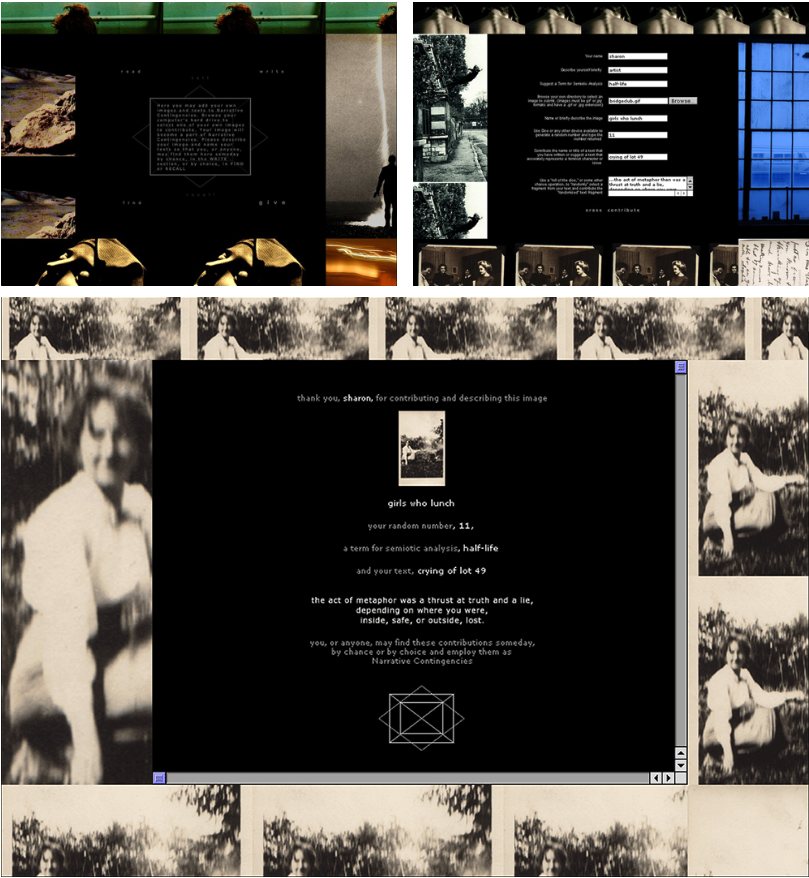

I encountered Bakhtin when I was working on an essay in which I used systems theory in an attempt to rethink subjectivity and subject–object relations within what I thought of as “collaborative systems”—a kind of umbrella term for a series of web platforms and place-based participatory media projects I developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In these projects (for example, Narrative Contingencies [Fig. 9-11], NeedXChange and Palabras [Fig. 12-13]) I experimented with the contribution, production, description and classification of what we would now call “user generated content” as a means to facilitate collective expression.

Figures 9–11: Narrative Contingencies (website offline). 2000. Screenshots.

Figures 12 and 13: Palabras (website offline). 2006. Screenshots.

At that time, I saw what I thought were useful parallels between Bakhtin’s dialogic, polyphonic, multivocal model for narrative, my own experience as a voice in the multi-vocal performance of polyphonic music and the model of autopoetic systems described by second-order Cyberneticists. In each case a whole is formed by the interaction of many entities (none of which is entirely absorbed into or objectified by the other), each entity retaining its subjectivity in intersubjective relation to the whole. Thinking through polyphony still informs how I engage with individuals and communities in the process of “field research” and in the design of data architectures and interfaces.

ODORICO: You position yourself within your work as a context provider. Could you explain what this means in relation to your role as an artist and author, and how it relates to the much-discussed concepts of collaboration and coauthorship within interactive documentary?

DANIEL: Yes, when I talk about my work I always say that I see myself as a “context provider”—as opposed to a content provider or storyteller. This is a way of explaining a shift in my role as an artist from creating content to framing a context—a space for those whose voices are not included in dominant socio-political discourse to speak and be heard. My goal is always to avoid representation (a primary agent of domination), not to speak for others, but to allow them to speak for themselves. To this end, I ask participating coauthors to tell their own stories and state their own opinions and positions through the direct address of the interview. My approach to the interview is informal and conversational rather than systematic or objective. Participants are encouraged to tell their own stories without mediation. My first question is always “what would you like the public to know about you, your circumstances, your politics, your history?” I pose this question while I’m putting a lavalier mic on the interviewee—I talk about making a recording—that it is intended to function as both testimony and evidence; a public record. I explain that I don’t yet know how the piece will turn out—that it will be shaped entirely by the arguments and perspectives of participants. But I make no pretence to objectivity—I hope the work will play some part in changing the material and social conditions of my coauthors.

ASTON: Expanding on this, is it fair to say that your work is essayistic—i.e. working with polyphony and heteroglossia to a very specific and clearly articulated agenda? If so, is there more that you could say about your rhetorical strategies through which to work through this agenda?

DANIEL: Yes, I would agree that my work is essayistic. I think that interface and information design constitute a form of “argumentation” (as writing does for a scholar), and a user/viewer’s navigation of an interface becomes a path of “inquiry” (a distillation and translation of the encounter through which the speech of the participants emerged). The data and interface are framed by what I think of as anecdotal theory—after Michael Taussig and Jane Gallop—which combines narratives drawn from my encounter with my interlocutors, with my own research and analysis. [1] This is where my own voice emerges. It is my hope that the passages of anecdotal theory, which can be found in the introductions and conclusions, as well as dispersed throughout the works, will create a point of entry for the viewer to become immersed in the subjective plurality within the work; perhaps this could also be thought of in terms of heteroglossia.

I think of an issue, like mass incarceration, as a landscape or “site” of socio-political and economic experience, rather than as a narrative. I engage an issue, like racist policing or environmental racism, as a “site” or a problem-space, rather than a narrative. I work to collect a significant amount of direct testimony—statements, histories, stories and arguments—offered by those most impacted within the problem-space. Then I design a database or information architecture to contain this testimony that maps out an extensive territory—say, one hundred square miles. Rather than building a single road across this territory to get from point A to point B, the interface sets the viewer down within its boundaries allowing her to find her own way to navigate a difficult terrain, to become immersed in it, and, thus, I hope, to have a transformative experience.

ODORICO: In our i-Docs 2018 panel on the “Poetics and Politics of Polyphony” you mentioned neoliberalism. Could you expand on this in relation to any sense of intervention and urgency relating to your work?

DANIEL: I brought this up in reference to the troubling dominance of storytelling and character-driven narrative in the field of documentary at this moment—a moment when I feel that interventions against structural violence, racism and inequality are urgently needed. And I don’t believe that the kind of empathy-generating, character-centred narratives that are the seemingly exclusive focus of funders and programmers at this moment can adequately address structural concerns.

Character-driven narratives that represent social injustice through the experience of a single individual tend to focus on the individual’s ability to transcend, to pull herself up by her bootstraps—or not. This is a neoliberal attitude, which assigns responsibility to the individual “central character” and produces sympathy in the audience without engendering a sense of a larger social responsibility. For me, critical engagement with hyper-scale structural inequality—like mass incarceration and environmental injustice—requires a more polyphonic approach.

Where one voice, an individual story, is intended to stand in for a class of subjects, there is a dangerous and disabling tendency to identify the subject as a case of a tragically flawed character or unusually unfortunate victim of aberrant injustice, rather than as one individual among many affected by structural inequality. When multiple voices speak, in a manner that is intimate and personal, collective and performative, from the same experience of marginalisation and oppression, the scale and scope of injustice are revealed. And through that revelation the viewer should recognise that the problem is societal; that it is not resolved by the narrative arch of an individual character’s transcendence or failure and that she (the viewer), as a citizen, is implicated and must take on some responsibility for change.

ASTON: Building on this, I’d like to ask a bit more about who you see as the prime audience(s) for your work, what your strategies are for reaching out to these audiences, and how much you see this as being your role within the context of being a media artist.

DANIEL: My ideal audience is anyone who hears the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and answers with “all lives matter”—this is just one possible indicator that someone hasn’t acknowledged or understood their own (often white, male) privilege or seen the world outside their own circle of privilege. So, I guess by that I’m saying my target audience is a large percentage of the general public and of policy makers. The question of outreach strategy and responsibility is so common on grant applications—along with “how do you measure the success of…”. But I never feel like I have the “right” answer. I’m committed to making work that is accessible online. This makes it easy to distribute. I know, anecdotally, that the projects are “taught” in a variety of academic contexts—from digital media courses to legal studies. I usually collaborate with nonprofit organisations that serve the interests of the communities I engage. I assist these organisations in using the project(s) in media advocacy. I haven’t yet managed to make inroads into the government and policy sectors. Clearly, in the US (and particularly in the era of Trump), the state is not susceptible to the persuasions of art, or the politicised speech of the incarcerated women, injection drug users, and native Alaskans I work with, but it is my hope that we can, at least, change the conversation. Brian Holmes argues in his “Affectivist Manifesto” that the role of art lies in its potential to increase an understanding of the possibility of change through expression that “unleashes” affect—in that sense each statement, each story, each voice carries the affective potential for things to turn out differently.

ASTON: Bakhtin talks about carnival as creating a situation in which diverse voices are heard and can interact, breaking down conventions and being a moment when things are permitted. Does this concept have any traction within your work and, if so, how can it be best used to critique, as opposed to reinforce, power structures?

DANIEL: I’ve never thought about my work in terms of “carnival” but I’m certainly involved in creating situations for diverse voices to be heard and interested in breaking down conventions. I think of making this break in a particular way, and I spoke about this at i-Docs this year. I’ve been working with a strategy I think of as Forensic Re-enactment, which is comprised of two kinds of gesture: materialisation and defacement. While the focus in the documentary field at the moment has turned toward virtual reality, I have been working on ways of materialising testimony—to embody speech as a stand-in for the absent body of the witness—and, at the same time I’ve sought to deface the material symbols of repressive power.

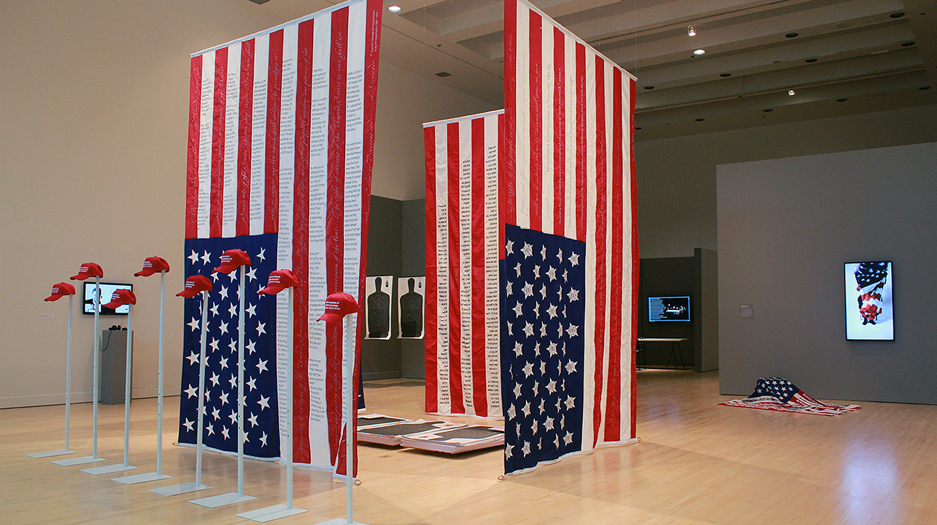

Figure 14: Undoing Time | Amends. University Galleries, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, 2017. Installation view.

An act of defacement is a mode of truth-telling. Defacement is a gesture of desecration—a transgression of a symbolic order that reverses and undoes the thing transgressed. Defacement is also embellishment: destruction that contextualises and illuminates. For the operation of defacement to work, the object must have an aura of the sacred or a code of rules for its treatment. For Undoing Time, I deface US flags that are sewn by incarcerated women in a California Prison sweat shop. To deface, destroy and, particularly, to burn the United States flag is a highly controversial but constitutionally protected form of protest. The US flag is supposed to be an emblem of democratic freedom and equality for all, but it is essentially a veil obscuring the systemic racism that continues to violate the civil, human, and constitutional rights of people of colour. For Undoing Time, I have defaced the US flag by embroidering the statements of men and women in prisons across California—prison labourers whose voices are rarely heard in debates on criminal justice policy, legislation and governance—into the stripes of flags that are produced in prison factories.

Figure 15: Undoing Time | Pledge. STUK Kunstencentrum, Leuven, Belgium, 2013. Installation view.

In Undoing Time | PLEDGE, a video portrait coauthored with former prisoner Beverly Henry (who worked in a California prison flag factory while incarcerated) is installed with two American flags produced in the flag factory where she worked. The text of an op-ed piece Beverly wrote on the 254th anniversary of Betsy Ross’s birth is embroidered into the stripes of the flags. In the video Beverly performs a symbolic act—undoing the stiches of one of the flags made in the prison factory while she describes her own search for equality and democracy as a socio-economically marginalised person.

Figure 16 (left): Undoing Time | Pledge. 2013. Video still.

Figures 17 and 18 (centre and right): Undoing Time | Amends. 2017. Detail of “Excessive Force” flag.

Undoing Time | Amends addresses specific ways in which the constitutional rights of prisoners and poor people of colour are violated by the criminal justice system. Embroidery on four 8x12-foot flags juxtaposes quotations from constitutional amendments and related Supreme Court decisions with the testimony of individuals whose rights have been violated. For example, the white stripes of one of the flags are embroidered with a section of the fourth amendment to the constitution, which protects against “unreasonable searches and seizures”. The red stripes are embroidered with a statement by Justice William O. Douglas from his dissent in the 1968 case of Terry v. Ohio (in which the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the practice of “Stop and Frisk”). Each of the fifty stars in the star field of that flag bears the name, age, location and date of death of an unarmed black man or woman killed by police in the past four years. In front of the flag hang three black hoodies riddled with holes that duplicate the pattern of bullet wounds in the autopsy reports for Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice and Laquan McDonald—who were all wearing hoodies when murdered by police.

Figures 18 and 19: Undoing Time | Amends. 2017. Installation detail of “Excessive Force”.

Figure 20: Undoing Time | Amends, 2017. Installation detail of “Excessive Force”.

Forensic re-enactment In Undoing Time is an operation in which the absence produced by mass incarceration and injustice in the criminal legal system is negated through a kind of rephysicalisation or reconstitution, not exactly a carnivalesque disruption but one that is intended to subvert conventions and to function simultaneously as testament, monument, and protest.

Note

[1] For me, Michael Taussig’s approach to writing, specifically in Defacement, Law in a Lawless Land, I Swear I Saw This and Beauty and the Beast, is both and influence and an example of what I think of as anecdotal theory.

References

1. Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The Danger of a Single Story.” TEDGlobal, July 2009. www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_ of_a_single_story.

2. Daniel, Sharon. “Collaborative Systems: Redefining Public Art.” Context Providers: Conditions of Meaning in Media Arts, edited by Margot Lovejoy, Christiane Paul, and Victoria Vesna, U of Chicago P, 2011, pp. 55–88.

3. ---. Undoing Time. 2017. www.sharondaniel.net/undoing-time.

4. ---. Undoing Time/Pledge. 2013. www.sharondaniel.net/pledge.

5. Gallop, Jane. Anecdotal Theory. Duke UP, 2002.

6. Holmes, Brian. The Affectivist Manifesto. 2018. brianholmes.wordpress.com/2008/11/16/the-affectivist-manifesto.

7. Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Continuum, 2004.

8. Taussig, Michael T. Defacement. Stanford UP, 1999.

9. ---. Law in a Lawless Land. U of Chicago P, 2003.

10. ---. I swear I saw this. U of Chicago P, 2011.

11. ---. Beauty and the Beast. U of Chicago P, 2012.

Suggested Citation

Daniel, S., Aston, J. and Odorico, S. (2018) ‘Polyphony in practice: an interview with Sharon Daniel’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 15, pp. 94- 105. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.15.06.

Sharon Daniel is a media artist who produces interactive and participatory documentaries focused on issues of social, economic, environmental and criminal justice. Daniel builds online archives and interfaces that make the stories of marginalised and disenfranchised communities available across social, cultural and economic boundaries.

Judith Aston has an interdisciplinary background in film, anthropology/geography and interaction design. She has more than twenty-years’ experience of working across industry and academia as a pioneer in the field of interactive/immersive media. She has developed and advised on cutting-edge projects with organisations such as Apple Computing, the BBC, the Bristol Old Vic Theatre, and Ffilm Cymru Wales, and has an international reputation for her research in and through practice. She teaches in the Filmmaking department at UWE– University of the West of England, Bristol, is a cofounder/director of i-Docs, and coeditor of I-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary (2017).

Stefano Odorico is a Reader in Contemporary Screen Media at Leeds Trinity University, Research Fellow in Film and Media at the University of Bremen and Associate Director of IRIS (International Research Centre for Interactive Storytelling, Leeds). His current work focuses primarily on interactive factual platforms and transmedia complexity. He has recently concluded a fully funded three-year research project on Interactive Documentaries (DFG– German Research Foundation). He has published numerous articles in international journals and anthologies on film and media theory, media practice, documentary studies, urban spaces in media, new media and interactive documentaries. He is a cofounder and member of the editorial team of Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media.