The Last Goldfish

Su Goldfish, Joanna Newman, and Julie Ewington

Introduction

The Last Goldfish is a feature documentary written and directed by filmmaker Su Goldfish. The film premiered at Sydney Film Festival, Australia in 2017. Multilayered and rich in personal archival footage, this intimate film tells a story of escape, rescue and loss that the director’s father, Manfred Goldfish, had kept hidden from her for many years. A refugee from Nazi Germany, Manfred and his first wife Martha escaped to Trinidad and Tobago in the then-British West Indies, where the filmmaker was born.

The Last Goldfish reflects on the intergenerational impact that the experience of displacement of the filmmaker’s father continued to have on his descendants. It reminds us that Australia is a country where many of its citizens have been touched by forced migration or a refugee experience. It is a country where the past reaches out, as always, to the present.

At Sydney Film Festival, The Last Goldfish was curated into a programme that included a number of other films responding to the distress and challenges of the current refugee crisis. Sea Sorrow (Vanessa Redgrave, 2017) was a plea to allow more children into Britain from the refugee camps in France. The film featured Lord Dubs, a vocal advocate for the children, who himself was rescued by the Kindertransport project in the Second World War, which saved the lives of thousands of Jewish children. Also premiering in Sydney in 2017 was Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time (Behrouz Boochani and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, 2017), which is discussed elsewhere in this issue. This moving documentary is a powerful depiction of life behind the barbed wire of the Manus Island detention camp maintained by the Australian Government to house asylum seekers and refugees arriving in the country by sea. The film detailed the day-to-day experience of refugee, artist and journalist Behrouz Boochani, one of the film’s directors, who made it on his mobile phone while held on Manus Island.

This collection of texts is a response by three writers to The Last Goldfish. The first section is by the filmmaker Su Goldfish. She writes about the children and families still detained in 2018 by the Australian government on the island of Nauru, comparing their current trauma to the experiences of her father and half-brother Harry, who were interned in Trinidad during the Second World War. Harry’s story threads through the film; he suffered mental illness for most of his life. Goldfish now makes explicit the connection she sees between her half-brother’s life and the children on Nauru; they were and are marooned on islands as a result of very different conflicts and for very different reasons, but these children have all waited for governments to rescue them and their families from uncertain futures.

The second text is authored by historian Joanna Newman, whose extensive research on the Jews who escaped to the West Indies informed Goldfish’s film. Newman’s work detailed the government policies of the day, made in reaction to the rush of Jewish refugees fleeing the violence in Europe. These included “turn back the boat” policies and, because of the war, the establishment of internment camps and detention camps. When war was declared in 1939, refugees of Austrian and German descent, though stateless, were deemed enemy aliens. Su’s father, from the group of 600 Jewish refugees known as the Calypso Jews, was one of many interned for various lengths of time on the island.

The third text is a critical review of the film by curator and writer Julie Ewington, reflecting on the unspoken histories, hidden traumas, scattered families and lost homelands that the film traverses. Ewington suggests that the filmmaker’s gradual understanding and acceptance of her father’s need to leave his past behind, as a resilient and protective response, is what ultimately gave him hope. For Goldfish personally, the revelations she uncovers in the film have led to new family connections and understandings.

I. Losing Harry

Su Goldfish

Figure 1: Link to video excerpt (2’2”) “Losing Harry”, from The Last Goldfish (Su Goldfish, 2017). Carolyn Johnson Films, 2017.

On Monday 27 August 2018, the 7:30 Report, a news programme on Australia’s national broadcaster, ABC, stated that, as of May 2018, Australia is responsible for the detention of 137 children at the Regional Processing Centre on Nauru. In the report Dr Vernon Reynolds, a specialist child psychiatrist who worked with these asylum-seeker children, tells us of their despair:When I first went to Nauru, there was always a degree of self-harm happening. There’s no doubt that over my time there, it became a more frequent event …What we see is these young people and adults basically withdraw from life and generally take to their bed and their whole functioning deteriorates. So, they stop eating much they stop drinking much … They stop interacting with people, they stop talking. (“Healthcare Workers Speak Out”)

“Losing Harry”, the video at the beginning of this section, is an excerpt from my feature documentary The Last Goldfish. The film tells the story of my father Manfred Goldfisch, a Jewish refugee who fled Nazi Germany with his first wife Martha in 1938. They escaped to the island of Trinidad, then part of the British West Indies. In Trinidad, he would change his name to Goldfish, a detail he would keep from me. The film reflects on the impact my father’s experiences had on him, and follows my decades of attempts to learn what happened to his family. It was a long and frustrating search, as my father’s response to trauma was to never speak about the past.

However, my intention in making this film—besides documenting the personal impact of uncovering my own family story—was to make connections with forces at work in the world today. The film becomes a lens through which I look at the combined impact of racism, nationalism and forced migration on ordinary people. I hope the film will remind viewers that the current refugee emergency is not the only time the world has faced such a crisis. Many of us in Australia come from refugee backgrounds: the kindness of ordinary people, advocacy and good government policy has given us a new home.

Figure 2: Manfred Goldfisch and Martha Goldfisch (later Wagschal née Golding) a year before leaving Germany for Trinidad in 1937. From The Last Goldfish. Carolyn Johnson Films. Screenshot.

Reviewer Lauren Caroll Harris notes this about the film:

As far as any summary goes, the Goldfisch to Goldfish story is a deeply compelling one, drawing together any number of stories—of 20th Century migration and displacement, of arbitrary and shifting yardsticks of race, of yearning and family and belonging and home—into one, divided family tree that unfurls over 80 minutes. But in memoir it’s not enough to have a compelling plot: a deeper theme must be extracted and made universal … The Last Goldfish summons purely through its narrative and spoken elements a world of swept-away homelands. To travel on a passport for stateless people; to be a Jewish refugee deemed an enemy alien by British colonial authorities; to move someplace you’d never heard of before. And in the generations that follow, to keep stitching your family around you, despite being scattered by history, despite homelands being swept away. To have, as Manfred feels he had, nothing and no-one to return to. (241–2)My father’s displacement also affected his children. I am the youngest of the three of us; my mother is Manfred’s second wife, Phyllis. The story of his first child, my half-brother Harry, threads through the film. I didn’t meet Harry or my half-sister Marion until I was in my thirties and I quickly realised that Harry had been deeply affected by his experiences as a child of refugees, as well as the subsequent breakdown of his parents’ marriage. Harry was born on 12 October 1939 and was barely a month old when Germany invaded Poland and war was declared. His parents, Manfred and Martha, though refugees, were German and deemed enemy aliens. They had been in Trinidad for less than a year, struggling to learn English and to make a living. The outbreak of war had brought even more uncertainty into their lives.

Some of this I learned after my father died when amongst his few belongings I found a series of stories he had been writing of his early experiences in Trinidad. Early on, Manfred had been separated from his wife and small son and imprisoned on an island in the harbour off Port of Spain while the authorities built an internment camp on the mainland. Martha was left on her own to care for baby Harry. It would be three months before Manfred would be reunited with his wife and little son. My father wrote: “Most of us felt overjoyed that we would meet our families again, tempered by the knowledge that really we only were being transferred to a larger prison”. The internment camp they were moved to was called Camp Rented and housed Germans and Austrians, mainly Jews, who had fled persecution. My brother Harry spent the first few years of his life in this camp with a group of what I can only assume were traumatised and distressed people. Camp Rented was not an inhumane place, and the internees were treated respectfully, but there was barbed wire and they were not free to leave. For many of the Jewish refugees who had fled racist violence, and still had family in Europe, imprisonment felt deeply unjust and drove many to despair.

My father wrote that the internees tried to make life normal: “We … settled down to a routine of work, rest and play which allowed us to remain reasonably sane. Even so there were difficulties, squabbles broke out and people got irritable, fathers beat their children and husbands and wives accused each other of planning illicit affairs”. It was cramped and claustrophobic, and their lives were on hold. In the film I imagine my father’s state of mind at the end of the war:

VO: News is emerging about the concentration camps.

Manfred told me;

“My parents wrote to me regularly, but then the letters stopped.”

And the hardship of being imprisoned has taken its toll. His marriage ends.

Manfred fights for custody of the children but he loses them.

My brother remembers Manfred coming into his bedroom with a suitcase to say goodbye and to tell Harry that he loves him.

And Martha, the only person who knows Manfred, his family and his life in Germany, takes the two children and leaves for Canada. (Goldfish)Of my father’s three children Harry was the one most affected by his parents’ experiences as displaced people. His struggle with mental illness is revealed through the film; his feelings of abandonment; his dreadful crippling anxiety and depression. Harry was fearful that terrible things would happen to the people he loved and that he would not be able to keep them safe. His anxiety in the end left him unable to work or travel. He died of drug-induced Parkinson’s disease from all the medications he had been taking over the years: he was only 71.

I trace Harry’s anxiety back to his childhood. His parents, my father Manfred and his mother Martha, were deeply distressed people who by the end of the war had lost their parents, members of their families and some of their friends in concentration camps. Their lives as they had known them had vanished. After the war, his parents’ bitter divorce meant Harry, from the age of twelve, would never see his father, Manfred, again. When I finally met Harry in my thirties he would speak constantly about the effect the experiences of his childhood had on him. I hope my film makes the connection between then and now, and how the experiences of traumatised and displaced people can impact on their children. I am trying to signal that transgenerational damage can be done. Now as I watch the 7:30 Report I can only think of the untold damage being brought to bear on the children trapped on Nauru.

The Australian Human Rights Commission’s website states that in 1990 Australia ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The convention sets out very specific requirements to protect the rights of children, including that “children must only be detained as a measure of last resort” and “children must only be detained for the shortest appropriate period of time” (“Information”).

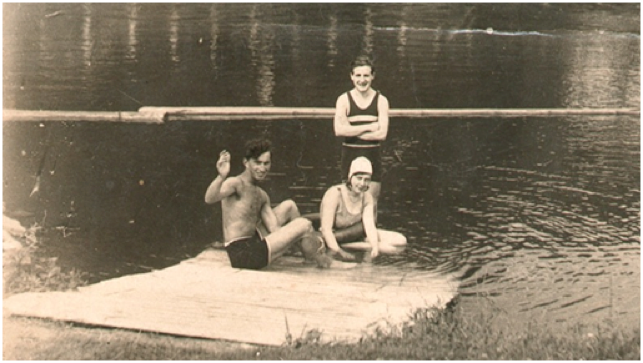

Figure 3: Harry and Marion Goldfish (later Wagschal), circa 1945, Trinidad and Tobago.

From The Last Goldfish. Carolyn Johnson Films. Screenshot.

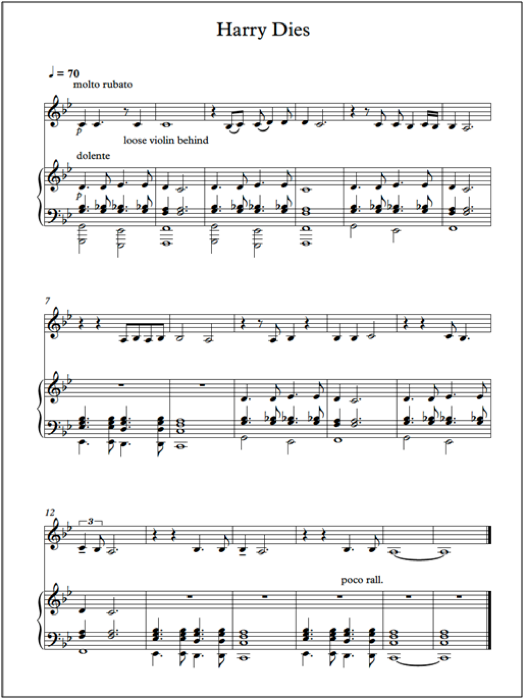

Manfred, Martha and Harry were only interned for two, possibly three, years. Harry was three or four when they were released. The children and families on Nauru have been imprisoned much longer than that. In the ABC 7:30 Report, Fiona Owens, a mental health team leader says: “There’s no research on what happens to children when they’re in detention for five years. So these children, these families, are unique in that we don’t understand what’s happening to them” (“Healthcare”). My brother Harry’s debilitating mental illness was hard on his partners and his children. My nephew Gerry in a Q+A after the film screened at the New York Jewish Film Festival 2018 spoke about being deeply affected growing up with a father who was mentally ill. If only he had understood that at the time, he told the audience. The impact continues to the next generation.Composer Liberty Kerr wrote the score for The Last Goldfish (Fig. 4). In the video excerpt at the beginning of this article you hear the music she wrote for Harry; the sound design is by Yulia Akerholt. I realise, the musical notation that describes the expression and feel of the piece is poignantly apt; “molto rubato” refers to “tempo rubato”, which means literally stolen time, and “dolente” means sad.

Figure 4: “Harry Dies” from the score by Liberty Kerrfrom The Last Goldfish.

Courtesy of the composer.

II. InternmentJoanna Newman

When Su [Goldfish] invited me to respond to “Losing Harry”, I was not sure how a historical narrative would fit within such a powerfully personal account of the lasting impact that trauma and displacement has had on the lives of the Goldfish family. So, what I have done is to provide the historical context to which Manfred, Martha and their two children came to Trinidad, as well as observations on the detention that refugees who found sanctuary on this Caribbean island experienced.

I first met Su through my PhD from the University of Southampton, Nearly the New World: Refugees and the British West Indies 1939–1945. We corresponded and then met in Sydney a few years before she completed her documentary The Last Goldfish. I was able to provide the background to the story she was researching about her father and his family and we have both discovered how the repercussions of Su’s search for her own family’s history intertwines with my historical interest in that period.

In November 1938, shortly after the organised pogrom that took place across Nazi Germany, Manfred Goldfish made the decision to leave Germany. He used up the last of his savings and journeyed with his wife Martha to Trinidad on the steamship Cordillera. In a manuscript written years later in Australia, he remembered saying goodbye to his parents, with the feeling he would not see them again. In 1942, his parents were deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp where they died within a year of each other.

Figure 5: View from the MS Cordillera (1938). From The Last Goldfish. Screenshot.

Why did they choose Trinidad in the first place? By mid-1938, the refugee crisis in Europe was worsening as Nazi policy changed from legislative persecution to violence and forced expulsion. Thousands were arrested and detained in camps, their release given on the condition that they left Germany immediately. Yet, most countries of immigration, such as the United States and Britain, were closed to refugees who did not have employment or financial guarantees waiting for them. As refugees (and agencies on their behalf) scanned the world, destinations that did not require visas gained in importance. Trinidad was one of the few places in the British Empire that only required a landing permit. This meant that by the beginning of 1939 the Colonial Office in London had received over 2000 applications by refugees to travel to Trinidad (Newman 173). By January, there were some five hundred refugees there, who arrived on boats daily from ports in Germany and Austria. Manfred and Martha Goldfish arrived in Port of Spain on 1 January 1939, just two weeks before the Trinidad Authorities imposed a ban on further refugee entry.

The Goldfish family were able to settle in Trinidad and Manfred found work on the docks, but with the outbreak of war, the refugee community’s new lives were disrupted. As was practice across the British Empire, at first only small numbers of refugees were detained, but by 1940 mass internment was carried out. In Britain, by December 1940, public opinion had turned against mass internment, particularly after the mass deportations of internees to Canada and Australia and the torpedoing of the Arandora Star in July 1940. By the end of August 1941, only two internment camps were left on the Isle of Man, compared to the earlier nine internment camps in the British Isles. By the end of 1944, only Nazi sympathisers and prisoners of war were left interned.

In Trinidad, four camps had been established by 1941. A prisoners-of-war camp was established on Nelson Island. An internment camp, Camp Rented, and a detention camp were set up in St. James, near the capital Port of Spain. All refugees of enemy alien nationality were placed in the internment camp and Jewish and non-Jewish internees were separated from the beginning. The internment camp consisted of eleven huts and was divided into two sections, one for Jewish internees and one for non-Jewish internees.

Refugees in the West Indies were only released if they could re-migrate or if financial guarantees were provided. The specific laws to grant detention and internment powers differed in each colonial British territory, but the categories for detention were broadly similar. Category A were interned without exception under a general order; category B were interned in the absence of a specific recommendation against by the Aliens Investigation Committee; and category C cases were dealt with on an individual basis. Refugees in Trinidad found themselves included in each category, but the majority had the “enemy alien” category B and C tag. This partly stemmed from a belief that, however persecuted refugees might be, they may still retain loyalty to the country that had oppressed them and stripped them of their citizenship. In the case of many refugees arriving in Trinidad, at the point when the majority came on release from concentration camps, this was particularly iniquitous.

Alongside Manfred Goldfish’s memoirs of his family’s internment, written in Australia in 1983 is this account from Hans Stecher, who was fifteen when he arrived in Port of Spain from Vienna with his family in 1938. Hans wrote that the women were initially taken to Caledonia, the men to Nelson Island:

Within sight and shouting distance of each other; not far away is Carrera, the official prison island, and the waters around the area are said to be shark-infested … I was young enough to see mostly the beauty of our surroundings and played down the unpleasant parts of the situation … They [the elders] could not help but feel bitterness and resentment at being thus mistreated, of being deprived of their newly found freedom and having just sent out new roots, being so abruptly and rudely uprooted once more. The stigma of being branded “enemy alien” was almost intolerable to us. (Stecher)

Figure 6: Nelson Island, Trinidad and Tobago. Photo by Su Goldfish, 2006.

The male refugees remained on Nelson Island for a few months before being transferred to Camp Rented, built specially to house them. At this point all other refugees of enemy alien nationality were interned, including wives and children. The camp was barrack-style, subdivided into a number of rooms so that families could live together. The internal affairs of the camp were run along the same lines as internment camps in Britain, a camp leader being elected from amongst the refugees, and a camp “commander” appointed by the British. The camp leader was a refugee from Frankfurt, Paul Richter, whose wife had been a German tennis champion. In the camp, classes were organised in English and Hebrew. Lectures were given in physics, chemistry and other sciences by Dr Laban, a refugee dentist. Children attended school outside the camp.

As in Great Britain, the majority of refugees were interned between May 1940 and December 1941. In March 1941, Chaim Weizmann, Zionist leader and future first President of Israel, visited the Trinidad internment camp to discuss with the Governor the conditions of release for the last remaining refugees there. Most of those left in the camp were too elderly to support themselves and relied on the camp for accommodation and food. In January 1944, sixteen refugees remained interned and, at the end of the war, four remained: aged, with no destination to go to, and entirely dependent on aid.

The long period of internment disrupted attempts to settle and, for some, this experience led to a sense of despair. Echoing the memoir of Manfred Goldfish, Hans Stecher also recounts the boredom and desperation felt by some:

We spent more than three and a half years in detention and […] many […] felt defeated and hopeless. The close proximity of living also caused people to get onto each other’s nerves […] Dr Karell, a Doctor of Philosophy, became deranged; started to sit on the floor and to proclaim that he was the reincarnation of Abraham. An old man, Mr Blei, unfortunately hung himself. (Stecher)

Figure 7 (above): Hans Stecher (R) and his parents, Trinidad and Tobago, circa 1950s.

Figure 8 (below): Jewish Dramatic Group, Trinidad and Tobago, 1943. Front row: Gizi Feiner; unknown; Nunia Sadovnik. Second row: Yasha Medvejer; unknown; Aron Szydlowicz; Biba Schecter; Samuel Oszslack; Ronea Rabinovitch; Moye Zonensein; Thora Yufe; Lorna Yufe; unknown. Third row: Buze Schechter; Leo Katz; Golda (Gusta) Zonensein; Salo Gross; Bubi Schneider; Willy Turkenwiez. Back row: Mr. Bialogorodsky; Idel Rabinovitch; Moishe Steinbok; Egon Huth; Reynold Strasberg; unknown; Michael Strasberg. Names provided by Libby Ellyn’s mother Lorna Yufe, and Zeno Strasberg. From The Last Goldfish. Carolyn Johnson Films. Screenshots.

Once released, refugees were not free, but remained subject to the Aliens Restriction Order, which entailed reporting daily to a police station, remaining in Port of Spain and being subject to a curfew. Internment and this Order had already disrupted the lives of many in the Jewish community. Once it had come into effect, some 150 Eastern European Jews who had settled in San Fernando were compelled to move back to Port of Spain, thus losing their livelihoods and becoming dependent on aid from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).Internment undoubtedly destroyed early attempts to settle in Trinidad and contribute to the economic development of the colony. Before the outbreak of war, many refugee families had started small businesses, and the JDC’s economic survey of the Island in 1939 was buoyant about the prospects for the refugees to both settle and become self-reliant.

Once war had been declared, refugees struggled with the moniker “enemy alien”, and with accusations of dual loyalty and fifth-column activity levelled at them. This added to the sense of trauma felt by those recently arrived and struggling with the experience of exile and leaving family behind. When mass internment was carried out in 1940, The Trinidad Guardian,which had been sympathetic to the refugees’ plight and supportive of their settling in the colony, became more circumspect in their support. On 28 May 1940, for example, The Trinidad Guardian’seditorial was titled “The Fifth Column” and argued that:

Some of the Jewish enemy aliens who have found refuge here from the horrors of Nazism have written suggesting that our campaign [for internment of enemy aliens] was based on anti-Semitism [sic] and appealing against internment on the ground that it is impossible to be a Jew and also a Nazi. No fair-minded person will deny that there is merit in the statement that it is extremely unlikely for any Jew to be a Nazi. It must also be remembered, however, it is still very possible to be a Jew and remain a German. (6)

The editorial continued by saying that Britain was at war with “the whole German people whose warlike spirit and lust created the fertile foundation on which Hitler and his gang of murderers were able to build a regime of lust such as Nazism” (6).

Most letters agreed with this view and the Jewish Association of Trinidad (JAT) replied with a passionate defence of their position:

To the Public of Trinidad: Remarks have been publicly made that many of the Jews here in Trinidad are German spies … this is an absurd charge for the Jews of the world have no greater enemy than present day Germany … We ask the people of Trinidad that all remarks against us as German spies cease. (“Letter” 6)

Appealing to the “British spirit” they continued: “To make wanton attacks without proof against us Jews smacks too much of the German spirit: for that is the true German method. True British spirit is what we ask for and expect from everyone in Trinidad” (“Letter” 6). The JAT also wrote to the Government of Trinidad, stating: “In this hour of crisis we Jews of Trinidad wish the Government to understand and believe that all of us, including those who have emigrated from German soil, are intensely loyal to Great Britain and pledge our complete support” (“Letter” 6). Sensitivity ran so high that the JAT also ran a campaign to discourage the use of German, stating that “it is not to be employed unless absolutely necessary in correspondence to those who do not know any other language” (“Letter” 6). As this overview shows, then, to be traumatised, stripped of your nationality and stripped of your language is a condition that faced refugees then and continues to face exiles today.

III. Citizen of the World: A Response

Julie Ewington

All children know that their parents keep secrets. In Su Goldfish’s family in Sydney, Australia, the secret was trauma: her father’s flight from Nazi Germany soon after Kristallnacht in 1938, her Jewish family never mentioned, whole histories left unspoken. Like so many other survivors, Manfred Goldfish spent the first years of his daughter’s life determined to put past sorrows behind him, looking only to the future, with only temporary success. At fourteen, Su Goldfish finds the first clue to Manfred’s former life—her father is divorced, and has another family in Canada—and over the next five decades she will gradually uncover his secret, and learn that she is, as Manfred eventually tells her, “the last Goldfish”.

Figure 9: Manfred Goldfish and Su Goldfish in 1960. From The Last Goldfish. Screenshot.

Su Goldfish’s eighty-minute documentary film has been more than a decade in the making. This extended gestation has left many traces in the film itself. The Last Goldfish is impeccably researched, and rich with visual information: Manfred’s photographs and home movie footage, Goldfish’s own photos and those of family and friends, innumerable letters and documents, Manfred’s typewritten stories and, eventually, interviews with his contemporaries from Germany—Martha, his first wife, and his friend Gretel Bergmann, a great athlete. It is a miracle of editing: this abundant material is impeccably managed by Martin Fox’s taut timing and orchestrated by Yulia Akerholt’s wonderful sound.

This rhythmic economy is the film’s first accomplishment. It sets the mood for each chapter of revelations: glorious golden images of Trinidad, “this island of my childhood”; the urgent tone of Goldfish’s teenage impatience with her father’s evasions (“I just want to be a citizen of the world” is Manfred’s stock reply); and the bright-cut steel-band music behind her exploration of the astonishing story of the Calypso Jews, the scant 600 who managed to reach Trinidad before the British closed the country and that avenue of escape to European Jews. Eventually, after Su’s joyous meetings with family in Sydney and siblings in Canada, her elderly parents die: the tender footage of Manfred and Phyllis in old age is extraordinary. Now the mood becomes more ruminative, melancholy. Goldfish inherits the full weight of the family’s sorrows, the exacting burden Manfred had tried to spare her: the deaths of her grandparents Eugen and Lina Goldfisch in the concentration camp at Theresienstadt, the disappearance of so many family members. Manfred’s grief was enduring. “I feel so guilty I survived”, he tells his daughter.

In the huge contemporary corpus of works by second-generation Holocaust survivors—books, films, documentaries—first-person testimony features prominently, usually as eyewitness interviews accompanied by an authoritative voiceover. The Last Goldfish is a testament, sure enough, but the crucial witness here is Su Goldfish: she voices her own generous conversational script, often dispassionate, sometimes bone-dry. The use of the continuous present is the clue: “We have no family in Australia”, “I am 20”, “My father is disappearing before my eyes”. Su says at the beginning of the film that it is about Manfred, but this is as much about her, a story in the present that began in the past. And it is an Australian story—peopled out of flights and diasporas, with hybrid families created from unlikely alliances, and sustained by Su’s community in Sydney’s vibrant lesbian and gay world, with its distinctive contemporary take on the inclusive extended family.

Figure 10: Su’s friends (left to right) Catherine Fargher, Maria Barbagallo, Anthony Babicci, Su Goldfish and partner Deborah Kelly, Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, 2000. The Last Goldfish. Screenshot.

This doubled witnessing is the second achievement of The Last Goldfish. Manfred is the ostensible subject, the “last Goldfish” of the title. Su says early in the film that Manfred “tells me stories, not always the truth”. The deliberate disjunction at the film’s core, and the structuring device that enables its love and commitment, is Su Goldfish’s insistence on her own account of discovering her father’s occluded life and its complex chronology. From the opening frame, when baby Su looks at her father’s camera on a Trinidad beach, Su Goldfish is both the vehicle and the subject of her own investigation. In one sense, this is ruthlessly methodical, even transparent. The film follows Su’s journeyings, and Manfred is revealed only through her research. His constant deferral ensures the excitement of the chase—“He never tells me what actually happened to him”—but the extended dialogue between daughter and father is also the torque that holds the film in a wonderfully productive tension.

The Last Goldfish pivots when an exasperated Su hands Manfred a camera during one video interview, asking him to describe people and scenes in his pre-war photographs. Manfred has loved cameras since childhood, beautiful German state-of-the art still and movie cameras, and Su has grown up with them. His recording of his life and family, her researching it, depends on these cameras, and what Manfred made with them. Handling the cameras prompts Manfred to open up: he tells Su stories about his youth, about the terrible events of 1938, his arrest in Königsberg, his release, a period in a prison camp before escape to Trinidad and, much later, to Australia. For if Manfred refused to look back at his memories, he never threw away their traces, which leads Su back to Germany in 2009, with her new German passport, to retrace her father’s pre-war footsteps.

Figure 11: Manfred Goldfisch (standing) with friends in the 1930s. From The Last Goldfish. Screenshot.

At this moment, The Last Goldfish enters its final elegiac chapter, haunted by a delicate theme for piano and cello by Liberty Kerr that underscores the gradual building of sorrow as Su searches for clues to her family’s disappearance. In Ulm, where her father’s family once lived, looking through the portal of her father’s photographs, she says: “I’m imagining myself back into their lives”. Blurred footage from a train window suggests that the camera is grasping for what can never be captured. In nearbyCologne, Goldfish is sober, pensive:“But now I am here, looking with his eyes, before it disappeared”. Before they disappeared.

So many died, so many changed their names to escape the past. Can pain be expunged? That is impossible. The past is remembered, though: with the placing of stones on family gravestones, and the making of this film, lost lives are honoured. Manfred and his story will be remembered. The Last Goldfish is a loving tribute from a daughter to her father, to his family, to her ancestors. In the film Su Goldfish asked Manfred, “Is there anyone left with our name?”. “No, you are the last one.” It’s a very precise answer. Some families changed the spelling, others sheltered under non-Jewish names. Su says: “I may be the last Goldfish by name, but I’ve found a sister and a brother, nieces and nephews, and cousins, lots of cousins, and I have my own family, my partner, my friends, my community”. After decades of research, Goldfish says she understands that her father had to move on, “to protect himself and me from the trauma of his past”, but like her Canadian nephew Gerry, she feels “less alone in the world” now she has found her family and its history.

This sense of communion has intensified for Su Goldfish since the film has been completed and shown at a diverse raft of festivals, such as Sydney and Adelaide (both 2017), and the New York Independent Film Festival and Frameline42: San Francisco LGBTQ Festival (both 2018), and through QANTAS’s in-flight screening program (2018). Echoing her father’s sentiment, Goldfish wrote to me in August 2018:

Flying high above the earth this film, in which I had tried to put forward an argument that we could choose to see ourselves as citizens of the world rather than being bound by nationalities or other identities, was playing way above the world. I received messages from travellers who cried all the way to Jakarta or wept above the Andes. The film was perfect in that air bubble for an intimate conversation on belonging and identity through headphones amongst the clouds and over many seas.

That said, The Last Goldfish is playing to many “families”—Jewish, gay, blended, Trinidadian, as well as Australian and American—and a striking result of the film’s release has been the emergence of other “lost Goldfish”, other members of Manfred and Su’s diasporic extended family who have come forward after seeing the film. Earlier I said this is an Australian story, which is to say it is a story known worldwide. In the little German river town of Bad Ems, what was once her grandparents’ kosher hotel has become a block of apartments run by Ahmed, a Kurdish Turk whose own family fled into exile, and who now welcomes asylum seekers and refugees from the Middle East. “There is a new history being made here”, says Goldfish. The last word from The Last Goldfish, in the film’s final frame, points to the contemporary global crisis of displaced persons and refugees. One wonders, what other lost stories lie beneath the surface of many seemingly untroubled families now living in the country historian Donald Horne famously called “lucky” in 1964. And will this sorrow ever come to an end?

References

1. Boochani, Behrouz, and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, directors. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Sarvin Productions, 2017.

2. “The Fifth Column.” The Trinidad Guardian, 28 May 1940, p. 6.

3. Goldfish, Manfred. Nelson Island Story. Unpublished memoir, 1983.

4. Goldfish, Su, director. The Last Goldfish. Carolyn Johnson Films and Su Goldfish Projects, 2017, thelastgoldfish.com.

5. Harris, Lauren Carroll. “I Thought of Home: Large and Small Histories in The Last Goldfish.” Kill Your Darlings, 20 Nov. 2017, pp. 240–43.

6. “Healthcare Workers Speak Out about the Health of Child Refugees on Nauru.” 7.30 Report ABC, 27 Aug. 2018, abc.net.au/7.30/healthcare-workers-speak-out-about-the-health-of/10170866.

7. “Information about Children in Immigration Detention.” Australian Human Rights Commission,6 Jan. 2016, humanrights.gov.au/information-about-children-immigration-detention.

8. “Letter to the Religious Committee.” Jewish Association of Trinidad, 30 Nov. 1939, Max Markreich Papers, Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

9. Newman, Joanna. Nearly the New World: Refugees and the British West Indies 1939–1945. 1998. University of Southampton, unpublished PhD dissertation.

10. Redgrave, Vanessa, director. Sea Sorrow. Dissent Projects, 2017.

11. Stecher, Hans. John. Unpublished draft manuscript. N.d.

Suggested Citation

Goldfish, Su, Joanna Newman, and Julie Ewington. “The Last Goldfish.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 18, 2019, pp. 128–144. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.18.10.

Su Goldfish is producer and manager of the Creative Practice Lab in the School of the Arts and Media at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. Su produces performance and media works, mentors students, and collaborates with academic staff and artists. As an independent filmmaker her feature documentary The Last Goldfish (81 min., 2017) premiered at the Sydney Film Festival, and has since screened around the world. It was awarded Best Foreign Documentary and Best Script for Documentary at the New York Independent Film Festival. Su studied documentary at the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS).

Joanna Newman is Chief Executive and Secretary General of the Association of Commonwealth Universities and is responsible for fostering and promoting inter-Commonwealth relations in the field of higher education. Before joining the ACU, Joanna was the Vice-Principal (International) at King’s College London. Joanna is a Senior Research Fellow in the History Faculty at King’s and an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Southampton and has taught history at University College London and the University of Warwick. In previous positions, Joanna represented the UK higher education sector as Director of the UK Higher Education International Unit. Newman’s book, Nearly the New World: The British West Indies and the Flight from Nazism, 1933–1945 will be published by Berghahn Books in September 2019.

Julie Ewington is a curator based in Sydney, Australia, writing on visual arts for journals including The Monthly and Art Monthly Australasia. Major publications include Fiona Hall (2005) and Del Kathryn Barton (2014). In 2017 Ewington was a curatorium member for Unfinished Business: Perspectives on Art and Feminism, ACCA, Melbourne.