Chauka Calls—A Photo Essay

Omid Tofighian

Chauka calls twice a day on Manus Island. For Manusians it signifies many things, including temporality, and it also represents homeland. But for the imprisoned refugees it reminds them that time has been suppressed since they were exiled to the island—they remain detained indefinitely and without charge. Chauka is also the name given by the Australian guards to the solitary confinement cell within the prison where acts of torture are committed. Testimonies in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time (Behrouz Boochani and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, 2017) describe examples of torture and crimes against humanity that correlate with allegations made by refugees since being incarcerated. Recently, lawyers have filed cases in the High Court of Australia for inflicting extremely harsh physical, mental and emotional affliction on people detained on Manus Island and Nauru (Davidson).

Figure 1: Manusian children living beside the detention centre in Lombrum, Manus Island (Papua

New Guinea). Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time (Behrouz Boochani and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, 2017). Sarvin Productions, 2019. Screenshot. All screenshots from Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time reprintedin this essay: Sarvin Productions, 2019.

I often hear Chauka chanting in the background when communicating with the film’s director Behrouz Boochani through WhatsApp and, like the Manusian people, he interprets the sound of the bird. Two dynamic relationships infused with meaning and purpose, two sources of resistance: a human being engaging with both nature and a smartphone.

Figure 2: “This film was shot clandestine [sic] with a mobile phone at Manus detention centre

in Papua New Guinea”. Dialogue from Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

Associate Professor Behrouz Boochani graduated from Tarbiat Moallem University and Tarbiat Modares University, both in Tehran; he holds a Masters degree in political science, political geography and geopolitics. He is a Kurdish-Iranian writer, journalist, scholar, cultural advocate and filmmaker. From 2013 to 2017 he was a political prisoner incarcerated by the Australian government in the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre (Papua New Guinea). Since being forcibly transferred in 2017 he continued to be incarcerated in one of three new prisons (East Lorengau Refugee Transit Centre). Boochani was writer for the Kurdish language magazine Werya; is Adjunct Associate Professor in Social Sciences at UNSW; non-resident Visiting Scholar at the Sydney Asia Pacific Migration Centre (SAPMiC), University of Sydney; Honorary Member of PEN International; and winner of an Amnesty International Australia 2017 Media Award, the Diaspora Symposium Social Justice Award, the Liberty Victoria 2018 Empty Chair Award, and the Anna Politkovskaya award for journalism. He publishes regularly with The Guardian, and his writing also features in The Saturday Paper, Huffington Post, New Matilda, The Financial Times and The Sydney Morning Herald. Boochani is also codirector (with Arash Kamali Sarvestani) of the 2017 feature-length film Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time; collaborator on Nazanin Sahamizadeh’s play Manus; associate producer for Hoda Afshar’s video installation Remain (2018) and the accompanying photography portrait series; and author of No Friend but the Mountains: Writing From Manus Prison (Picador 2018). At the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards 2019 his book won the Victorian Prize for Literature in addition to the Non-Fiction category. He has also won the Special Award at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, and Non-Fiction Book of the Year, Australian Book Industry Awards.

After almost daily reporting during the twenty-three-day siege and eviction from the original Manus Island detention centre (Lombrum Naval Base) in November 2017 Boochani’s international profile increased dramatically. When Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time premiered at the Sydney Film Festival earlier that year he was still incarcerated in the original prison from where he engaged in in-depth interviews and seminars over WhatsApp.Jeremy Elphick: One of the big things, Behrouz, is the fact that you weren’t able—or more, weren’t allowed—to attend the [world premiere of Chauka, Please Tell Us the Timeat Sydney Film Festival]. For people who aren’t familiar, I wanted to ask you why you weren’t able to be at premiere of this film?

Behrouz: In response to the rejection I was mainly thinking about the arts community in Australia. How is it that they allow liberal democracy, they allow a politician to make their decision like that about another artist? […] I’ve received a letter rejecting me… I made an application, even though I wasn’t going to come. I made an application for coming to Australia to attend the opening of my film. I received a rejection letter. I’m going to keep this letter and I’m going to use it and I’m going to publish it. Even if it’s 20 years from now. This is a historical document. It needs to go into the immigration museum. It needs to be made into a historical piece of history.

The fact that they refused an artist entry even though his art was being shown in the country. My question is how can they exile me to an island like this without a visa? I don’t have a visa to go to Manus? How could they exile me to Manus without a visa but refuse me a visa to come to Australia? This is a huge contradiction, an example of hypocrisy. I guess ultimately I’m not angry but I have a lot of criticism, a lot of concern for the arts community and their response to all of this. How can they let a politician determine the fate of an artist?

Jeremy: […] where you do think [the film] will end up? What impact would you like it to have?

Arash: There were different phases in this project and we had different hopes at different phases. In the beginning we wanted it to be a historical document. We wanted this to be documented in history. We didn’t want people to forget about it. We wanted to keep some historical presence, historical place. Then as things developed and it got accepted into the festival our hopes increased. Ultimately, in the end we realised that really the only hope that we can have is for it to just be a historical document, for it to confirm a place in history, for people not to forget in the future that this sort of thing happened (Elphick).

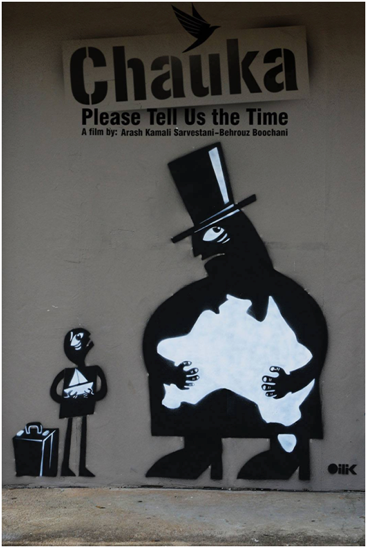

The film poster was designed by Brisbane-based visual artist Hesam Fetrati (Fig. 3). The codirector Kamali Sarvestani and Fetrati were introduced to each other through a mutual friend while planning the film. Kamali Sarvestani noticed a particular stencil art/graffiti work while previewing Fetrati’s art page and requested permission to use the image for the film poster; the artwork was painted on the wall of the Amnesty International office in Brisbane. The work is titled “Shared Australia” and was created in partnership with ARTillery and Amnesty International (“Art”).

Figure 3: Film poster by Hesam Fetrati for Chauka Please Tell Us the Time.

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time is also a meditation on time and a critical analysis of how it can be used as an instrument of torture—torture mechanisms that are targeted and systematic. There is no graphic violence depicted in the film, even though violence permeates all aspects of the prison; many of the shots are slow, long and mostly still. A significant amount of time is spent sitting, smoking, feet up on the fences, staring beyond the cage, contemplating, waiting.

Figure 4: Boochani smoking and contemplating with feet against the prison fences in

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

The distance between these fences and the ocean is under the cover of tall coconut trees, a whole variety of shrubs with broad leaves, and interweaving weeds. The coconut trees are even growing inside the camp. It is easy to imagine what a massive and pristine jungle stood here before the prison was built.The prison is like an enormous cage deep in the heart of the jungle /

The prison is like a grand cage next to the tiny gulf of water /

A body of water that merged with the ocean /

The tall coconut trees that line the outskirts of the camp have grown

naturally in rows /

But unlike us, they are free /

Their grand height allows them to peep into the camp at all times /

To know what is going on in the camp /

To see what is happening in the camp /

To witness the anguish suffered by the people in the camp.(Boochani 111–12)

Figure 5: Arash Kamali Sarvestani working in Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

Arash Kamali Sarvestani is an Iranian filmmaker and video artist. Kamali Sarvestani was born in Tehran, Iran on 1981. He studied cinema at the University of Art, Tehran. In 2009 he moved to the Netherlands to study video art at Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. He graduated in 2013 and has been living in the Netherlands since. Kamali Sarvestani has made more than twenty short films and video artworks in Iran and the Netherlands. In February 2015 he participated in a workshop led by Abbas Kiarostami in Barcelona. In addition to a close observation of Kiarostami’s style of filmmaking, this event presented a unique opportunity to understand the late artist’s character and views about life and art. At the workshop, Kamali Sarvestani made The Sea (2015), which has been shown in a number of festivals. The workshop that year coincided with reports of the particularly high number of refugees seeking safety worldwide and the political demonisation of them by politicians and the mainstream media. Kamali Sarvestani came up with the idea of making a film from inside a refugee camp. He was curious to know if it would be possible to make a movie about refugees using only mobile phone cameras inside a camp, which is more like a prison. In two years of researching the situation of refugees in various countries, he was particularly struck by the severity and underreporting of people detained by the Australian government on Manus Island and Nauru. Kamali Sarvestani eventually found Boochani who was (and still is) detained on Manus Island. He shared the idea with Boochani. Kamali Sarvestani’s first feature movie Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time is the result of their collaboration.

Boochani interviews a fellow detainee about the impact of his indefinite imprisonment on his family life and his wellbeing:

Just a few months ago I contacted my family… I pushed them really hard to spill the news that my wife had filed for divorce. And my son… Well, I haven’t seen him in three years. I was only able to talk to him, after two and a half years. He didn’t recognize me. He’s now five years old and he was two years old when I left to come to this wreck of a place. He doesn’t recognize me at all. I feel sorry for myself. Sorry that I’m still alive. I really prefer to be dead. Because I have nothing left anymore. No one is waiting for me, and I’m not waiting for anyone. I have lost everything. (Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 30:55–31:49)

Figure 6: In Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time, Behrouz interviews a refugee who had his

throat slit by a guard. Screenshot.

Look, just listen for a minute. You think you’re suffering more than me?

Who says you’re suffering more than me? Darling, you have your child with you. Your mum is with you, your father, your brother, all your relatives are with you.

I’m separated from all of you.

I’m separated from my child. I haven’t seen my flesh and blood yet.

Why are you doing this?

For God’s sake, you’re killing me with this.

Darling, things are out of my hands, I can’t do anything.

It’s completely out of my hands.

Nothing, it’s completely out of my hands.

(Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 11:00–12:00)

Figure 7: Calling home in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

Hi mum, how are you?

Are you alright?

I miss you very much…

Look mum… Please don’t cry. Please don’t cry.

Look, mum… Mum!

Let me talk to you for two minutes. Please don’t spoil it for God’s sake. Just two minutes.

Yes, I am fine. I’m fine.

Look mama, I’m stuck here.

You know that I’m stuck here and I have no control over anything.

It’s not like I’m enjoying myself here.

(Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 27:06–28:03)There were many people there. I saw some guys with wounds all over their wrists because of the handcuffs. Chauka was like four rooms. Two of them were opposite the other two. How can I describe it? Each room had two CCTV cameras on either side. The officers check on you once every hour. They were like: “What are you doing?” for no reason. They do it only to annoy you, checking every hour, night and day. (Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 20:12–20:45)

Figure 8: Recollecting Chauka, the solitary confinement cell. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

In Chauka, they held us there for another three to four days. There were three or four officers guarding us. Now, when I see them, several months later… when I see any of those guards again… I get goosebumps of fear and hate. That’s how much I hate them. I’ll never forget how they treated us. They really harassed us a lot in Chauka. Their behaviour completely altered my sense of self. It was like another world. You may laugh at me… Yes, you may laugh, but those 6 days I was in Chauka were harder than my whole time in this camp, that’s how badly they treated us. (Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 30:00–30:45)

Janet Galbraith is a poet and writer living on the unceded lands of the Jaara people. She founded and cofacilitates Writing Through Fences, a group that resources writers and artists incarcerated by Australia’s immigration detention industry. Galbraith’s work has been published in anthologies, literary and academic journals and newspapers including Cordite, Mascara, AFLJ, and The Saturday Paper; her multimedia work and poetry have been performed in festivals throughout Australia. Galbraith’s poetry collection re-membering was published by Walleah Press in 2013. Janet has numerous roles in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time: she is the journalist that raises questions and discusses issues pertaining to the prison, colonialism and Manus Island culture and knowledge; we hear her voice messages in the film which convey information from an Australian media editor; she helped transfer footage from Manus Island to Australia and then the Netherlands; and she has been a supporter of Boochani’s work and a confidant since 2014.

Figure 9: Poruan “Sam”, Clement and Janet Galbraith talk. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.Poruan “Sam” Malai and Clement Soloman, both from Manus Province, share their knowledge, history and traditions with Janet. They discuss the significance of the Chauka, the occupation of the island by the Japanese and the US during the Second World War, colonialism and neocolonialism. The Manus Island detention centre has had a destructive effect on their lifestyle, culture and social and moral fabric.

It is difficult to find refugees in the prison willing to participate in the filming. As an experienced journalist, Boochani moves through the detention centre, looking for people to engage with and locations to film. At the same time, he is wary of the pervasive surveillance. He understands the historical, political and aesthetic importance of this movie.

Figure 10: The corridor in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Sarvin Productions, 2019. Screenshot.The mosquito killer fogging machine comes through unannounced practically every day causing everyone in the prison to flee. There are clear messages in this strategy: you are as worthless as a mosquito, you are not wanted here, go back to where you came from.

Figure 11: Mosquito killer fogging machine in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

Hi, good evening. Do you remember Milad? Milad Platini, the one with the disabled leg. He has gone on a dry hunger strike for some days but they have paid no attention to him. Now he has cut his stomach with a knife. Now they are taking him to IHMS. (Boochani and Kamali Sarvestani 49:10–49:30)

Figure 12: Self-harm represented in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time represents the ugly and ruthless paradoxes of the modern, globalised world. It is an aesthetic and philosophical account of the biopolitics associated with indefinite detention and systematic torture, but it is also imbued with the rhythms of nature, the pristine beauty of Manus Island, poetry, song, dance, folklore and the inevitable melody created by the presence of children. In one of the final scenes a Manusian child smiles and dances playfully to a tragic Kurdish folk ballad being sung from within the prison.

Figure 13: Biopolitics, nature, children and folklore in Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

In 2016, the Papua New Guinean (PNG) Supreme Court ruled the detention centre in Lombrum illegal and unconstitutional. The doors were open for the first time allowing Boochani to continue his filming outside the prison. Parts of the film capture his early encounters with Manusian society, culture and people.

Figure 14: Indefinite detention. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Screenshot.

We are delighted and honoured to be presenting CHAUKA, PLEASE TELL US THE TIME (directed by Arash Kamali Sarvestani and Behrouz Boochani) within our Documentary Competition at the 61st BFI London Film Festival (4th–15th October 2017), and would like to take this opportunity to congratulate you on your remarkable film. The film will be in the running for the Grierson Award which recognises films with integrity, originality, and social or cultural significance.

It is our great pleasure to host the International premiere of the film and share it with London audiences. We would be truly honoured to have you attend the Festival for the scheduled screenings of the film on Sunday 8th and Monday 9th October 2017. […]

With gratitude and very best wishes,

Clare Stewart

Head of Festivals

Festival Director, BFI London Film Festival

(Zable)

Her Excellency Menna Rawlings

High Commissioner of the United Kingdom to Australia

3 September 2017Your Excellency,

My name is Behrouz Boochani, I’m writing this letter from Manus prison camp which is run by the Australian Government in Papua New Guinea. I’m writing in regards to the 61st London International Film Festival. I am a film director, and my movie “Chauka Please Tell Us the Time” (made with co-director Arash Kamali Sarvestani) has been accepted for the festival. It will screen on 8th and 9th October. This is a great honour for any director and I would like to attend the festival screenings. My movie was also selected to be shown in the Sydney Film Festival earlier this year, where it had its world premiere, but the Australian Government did not allow me to attend. I am asking you to give me a visa to attend the London Film Festival. I have been here in this prison camp for more than four years, even though I have committed no crime, and I am kept here by the Australian Government who exiled me by force.

Yours faithfully,

Behrouz BoochaniCC: Mayor of London, The Right Honourable Sadiq Khan

PEN International

BFI London Film Festival

Amnesty International

Geoffrey Robertson QC

References

1. “‘Art Should Create Questions’: Hesam Fetrati.” Amnesty International Australia. 27 Apr. 2017, amnesty.org.au/art-ask-questions-hesam-fetrati.

2. Boochani, Behrouz, and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, directors. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Sarvin Productions, 2017.

3. Boochani, Behrouz. No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison. Translated by Omid Tofighian, Picador, 2018.

4. Davidson, Helen. “Australia Subjected Refugees to Crimes Against Humanity, Class Actions Allege.” The Guardian. 9 Dec. 2018, theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/dec/10/australia-subjected-refugees-to-crimes-against-humanity-class-actions-allege.

5. Elphick, Jeremy. “Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time—An Interview with Arash Kamali Sarvestani and Behrouz Boochani.” 4:3. 14 June 2017, fourthreefilm.com/2017/06/chauka-please-tell-us-the-time-an-interview.

6. Galbraith, Janet. re-membering. Walleah Press, 2013.

7. Kamali Sarvestani, Arash, director. The Sea. Sarvin Productions, 2015.

8. Zable, Arnold. “From Manus to London: How Two Strangers Made a Landmark Movie Together.” The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 Oct. 2017, www.smh.com.au/national/from-manus-to-london-how-two-strangers-made-a-landmark-movie-together-20170926-gyow9k.html.

Suggested Citation

Tofighian, Omid. “Chauka Calls—A Photo Essay.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 18, 2019, pp. 205–217. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.18.19.

Omid Tofighian is an award-winning lecturer, researcher and community advocate, combining philosophy with interests in citizen media, popular culture, displacement and discrimination. He is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature, American University in Cairo; Adjunct Lecturer in the School of the Arts and Media, UNSW; Honorary Research Associate for the Department of Philosophy, University of Sydney; faculty at Iran Academia; and campaign manager for Why Is My Curriculum White?—Australasia. His published works include Myth and Philosophy in Platonic Dialogues (Palgrave 2016) and he is the translator of Behrouz Boochani’s multi-award-winning book No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison (Picador 2018).