In Search of a Lost Cinema: Cinephilia and Multidirectional Moving Image Memory in Golden Slumbers (Davy Chou, 2012)

Marie Krämer

Abstract

This article shows how creative approaches can contribute to a productive engagement with losses in film heritage. By (re)producing and (re)circulating images, sounds and narratives, documentaries on film heritage in particular relate to larger contexts of cultural and moving image memory. On the one hand, they are premediated by older productions, including feature films. On the other hand, they bring in new artistic, political and/or social perspectives. Golden Slumbers (Davy Chou, 2012), a documentary about Cambodia’s lost film heritage before the Khmer Rouge period, serves as an example to illustrate these ideas. It carries a dual perspective that is simultaneously post-migratory and marked by (French) cinephilia as a cinematographic memory culture. In order to do justice to this complexity, dynamic concepts from the field of memory studies such as Svetlana Boym’s notion of nostalgia and Michael Rothberg’s concept of multidirectional memory are drawn on alongside literature on the history and theory of (French) cinephilia. In this way, cinephilia is reimagined as a multidirectional moving image memory culture that plays a particularly important but also complex role with regard to film heritage. In conclusion, several questions are outlined that need to be explored in further research.

Article

In 1980, UNESCO recommended the preservation of moving images as part of national and global cultural heritage. Yet, as the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) estimates, “for some genres, geographical regions, and periods of film history the survival rate is known to be considerably less than 10% of the titles produced”. How can we respond to such significant losses and the consequences they might have for local and global cultural memory?

One solution might lie in new scientific research methods. In New Cinema History, for example, ethnographic methods are used to capture viewers’ memories and to gain information about films that have not been preserved.[1] Another solution, which this article addresses, is to deal creatively with such losses through the production of new films. In the last decade alone, numerous documentaries have explored cases of lost or threatened film heritage: Golden Slumbers (Le Sommeil d’or, Davy Chou, 2011) has reconstructed the traces of films lost during the Khmer Rouge era in Cambodia; Remake Remix Rip-Off: About Copy Culture & Turkish Pop Cinema (Cem Kaya, 2014) has drawn attention to the popular but not systematically safeguarded Yeşilçam production in Turkey; The Forbidden Reel (Ariel Nasr, 2019) has looked at threats to Afghan film archives under Taliban rule; and Talking about Trees (Suhaib Gasmelbari, 2019) has followed ageing Sudanese cinéastes as they attempt to revive the country’s film history. But do these films merely document what is left?

Following Dagmar Brunow’s “understanding of documentary filmmaking as an intervention into the audiovisual archive” (6), I will argue that documentaries on film heritage go far beyond that. Brunow defines the “audiovisual archive” as “the sum of images, sounds and narratives circulating in a specific society at a specific historic moment” (6). Hence, by producing and circulating new images, sounds and narratives, documentaries on film heritage relate to broader contexts of cultural and moving image memory. On the one hand, they are premediated by older productions, including feature films. On the other hand, by remediating these references, contemporary documentaries bring in new artistic, political and/or social perspectives.[2] In this way, they contribute to the transmission and actualisation of both the film heritage they engage with, and the cultural or moving image memory they refer to.

The case of Golden Slumbers provides a particularly rich example of these points. Faced with the near-total loss of Cambodian film production before the Khmer Rouge, filmmaker Davy Chou had little chance to draw on original material and therefore had to create new images of his own. As I will show, these images assume two perspectives: that of a “a second-generation diasporic film-maker” (Barnes 91) and that of a self-taught film lover or cinephile who grew up in France.[3] To analyse this dual perspective, I first lay out the historical and theoretical background of French cinephilia as a cinematographic memory culture. My analysis of Golden Slumbers then builds on Leslie Barnes’ post-migratory reading of the film and extends it to include its premediation through and remediation of cinephiliac references. I conclude with a summary of the “multidirectional” (Rothberg) dynamics at work in Golden Slumbers and outline some questions for further exploration.

Between Crisis and Activism: French Cinephilia as a Cinematographic Memory Culture

The French word cinéphile, which describes a passionate lover of cinema and has found its way into numerous other languages, came into circulation between 1910 and the early 1920s (Gauthier 18, 45). At this time, a growing fascination with film and the collective experience of cinema led to the founding of film clubs and magazines. Their followers developed common references, “ritual forms of conversing, writing, collecting, and exchanging ideas; techniques of memory” as well as “tactics for cultivating and sustaining enthusiasm” (Cowan 2). In the particular case of France, the disappearance of early films and filmmakers during the First World War made cinephiles aware that a historiography or systematic transmission of films had not yet begun. In keeping with the zeitgeist—which also saw the publication of Maurice Halbwachs’s Les Cadres sociaux de la mémoire (1925)—early French cinephiles became particularly involved with issues of cultural history and memory, including archiving and preservation. During the First World War, for example, the French army confiscated and melted down a considerable number of Georges Méliès’ works in order to recover silver and celluloid (Ezra 19); Méliès himself was presumed lost or dead. But in the mid-1920s, cinephiles fortunately managed to track down the filmmaker, who by then was working as a shopkeeper in a Paris train station, and recover some of his remaining films.[4] The conviction that underlay such efforts—that lessons could be learned from Méliès and other pioneers, as well as from their films (Gauthier 14–15)—might explain why French cinephiles were also quick to recognise the threat posed by the destruction of silent film prints. In 1936, their demands were answered and a national archive was founded to preserve France’s film heritage: the Cinémathèque française.

Its founding director Henri Langlois, however, was convinced that material preservation was not enough. Instead, he demanded that archived films be shown, seen, and discussed—that is, actively remembered and passed on to future generations. Following Aleida Assmann’s writings on archives as institutions of cultural memory, one could say that Langlois’s maxim “To show is to preserve” (Frick 170) aimed to counteract both active forgetting (e.g., through destruction) and passive forgetting, in which “objects […] fall out of the frames of attention, valuation, and use” (Assmann, “Archive” 98). Under Langlois, the Cinémathèque developed and pursued what Assmann would call a “strategy of the canon” by constantly reprogramming and reinterpreting older films (102).[5] A similar strategy can be found in the films of the French New Wave, which—like Langlois’s evenings at the Cinémathèque—not only reappraise film history, but also teach techniques of engaging with past films in the present (Frisch 109, 118–127). As “place- and timeless ciné-club[s]”, the films of the New Wave stepped out of their French context of origin and have become the subject of canonisation themselves (Krämer 107; my trans.). In this way, they have made a lasting contribution to the consolidation and dissemination of cinephilia in its French tradition, that is, as a cinematographic culture of memory.

A lasting influence of the French tradition is also evident in academic research on cinephilia. For instance, many scholars interpret cinephiliac practices—such as collecting, or watching films repeatedly—as expressing a preoccupation with loss and irretrievability (Willemen; Elsaesser, “Über”; Keller). Thomas Elsaesser even points out that “at the forefront of cinephilia [...] is a crisis of memory: filmic memory in the first instance, but our very idea of memory in the modern sense, as recall mediated by technologies of recording, storage, and retrieval” (“Cinephilia” 40). It is not surprising, then, that Golden Slumbers and other films on film heritage deal with situations where records have been lost, the idea of storage has failed, and retrieval is no longer possible. In most cases, the crisis can be overcome with the help of cinephiles, the memories they preserve and/or their abilities to remediate what remains. Cinephilia could therefore be seen as a practice or an “act of memory” of particular importance for film heritage (De Valck and Hagener 14). For Adrian Martin, cinephilia furthermore touches the sphere of memory politics. Martin understands cinephilia as “a tactical, cultural war machine” which can only be kept running if “the histories” of cinephilia are retold in a way that “is inspired enough [to] connect with some part of the scenario of our own war machine” (222, 223). Seen in this light, films about film heritage or past eras of film culture, for example, could be much more than just a nostalgic search for lost time.

How rich and complex cinephilia actually is as a phenomenon of cultural memory becomes clearer when we draw on approaches from memory studies, such as Svetlana Boym’s concept of nostalgia. Boym distinguishes between a “restorative” and a “reflective” type: while in the former case, nostalgia amounts to an idealised reconstruction of the past, in the latter it leads to a productive engagement with remaining traces and memories (XVIII). Regarding films on film heritage, this could mean, for example, “recreating” what has been lost, or using the void as inspiration.[6] Reflective nostalgia in particular holds the potential to “explor[e] ways of inhabiting many places at once and imagining different time zones” (XVIII). This makes Boym’s concept all the more interesting for reflections on cinephilia and its French tradition, which has spread and developed worldwide over several generations. Another approach that could specifically help us grasp the complex dynamics of a post-migratory background like in Golden Slumbers is Michael Rothberg’s concept of multidirectional memory. For Rothberg, collective memory is always “subject to ongoing negotiation, cross-referencing and borrowing” (Multidirectional Memory 3). Instead of assuming a competitive situation in which one memory suppresses another, he acknowledges “how remembrance both cuts across and binds together diverse spatial, temporal and cultural sites” (11). Applying Rothberg’s multidirectional approach to documentaries on film heritage, for example, might allow us to consider to what extent these documentaries create new communities of memory that transcend the actual space(s), time(s) and culture(s) of their respective cases. Taking Golden Slumbers as an example, I will now explain how (French) cinephilia simultaneously acts as a premediation and is itself remediated in this process.

Telling the Story of a Cinema without Images: Golden Slumbers as Cinephiliac Memory Work

Davy Chou’s documentary Golden Slumbers deals with the fact that of around four hundred films produced in Cambodia between 1960 and 1975, only about thirty have survived. This catastrophic loss of cultural heritage is interwoven with Cambodia’s traumatic past: Filmmakers and actors were considered “enemies of the people” by the Khmer Rouge; many of them were killed or disappeared. At the beginning of the film, a text insert explains the situation in Cambodia today: “All that’s left […] are a handful films in very poor condition, and a few survivors. The heroes of their parents’ generation remain unknown to young Cambodians”. Yet some memories of the films still circulate, connecting generations born before and after the Khmer Rouge as well as foreign-born descendants of emigrated Cambodians with their lost cultural heritage: “It is part of a folklore, because these films belong to a Khmer collective imaginary and to the cultural references of our parents. Some people of my generation […] knew of the existence of this film industry without ever having seen the films” (Chou, Sommeil 4; my trans.).

After searching in vain for original footage in French and Cambodian archives, Chou found cinephiles who had seen the films in their youth or shared remaining photographs, posters, and film songs on the internet. They alerted him to the existence of a few VHS copies, but as he wanted to reflect the situation of young Cambodians who are cut off from their film heritage, Chou decided not to use these copies (Sommeil 6–7). Instead, he chose to focus on interviews with survivors: his aunt Sohong Stehlin (the daughter of a producer), filmmakers Li Bun Yim, Yvon Hem and Li Yu Sreang, actress Dy Saveth, and two “cinephiles” (11–13). In addition, Chou uses film songs, situates the survivors’ testimonies in original locations, and repeatedly films young Cambodians, many of whom are members of his collective Kon Khmer Koun Khmer.[7] Through this multilayered construction, Golden Slumbers gradually reveals that Cambodia’s lost film heritage is still very much present and could become a source of new artistic creativity.

Figure 1: A flowering shrub grows out of the roof of the former Hemakcheat Cinema in Phnom Penh. Golden Slumbers (Davy Chou). Vycky Films/Bophana Production/Araucania Films, 2012. Screenshot.

In the following, I will focus on three aspects. The opening sequence illustrates the extent to which Golden Slumbers is premediated by the French tradition of cinephilia. Examples of the complex relations between old and young generations in Cambodia then show how references to cinephiliac classics are used to mediate between different audiences. Finally, scenes shot in the former Hemakcheat cinema reveal how Golden Slumbers not only echoes cinephiliac premediations, but also remediates and transforms them.Cinephiliac Premediations

Golden Slumbers begins with a night drive on a dirt road; the camera is in a vehicle that appears to be following two people on a scooter. With each match cut, the movement continues as the surroundings gradually become brighter. Yet there is an uncanny feeling of disorientation:

[F]or an instant the viewer feels suspended, suddenly deprived of the points of reference that would anchor her in relation to the image on the screen. It becomes clear […] that […] the footage is being played in reverse. Dawn is in fact dusk. We are simultaneously looking forward and backward […] we experience both the future as the immediate past and the past as present before us. (Barnes 80)

Meanwhile, the voices of two men can be heard talking in Khmer about films they saw around 1970. While the men are engaged in their dialogue, the viewer has the impression that the sun is rising. The two cinephiles thus seem to shed a first light on the darkness that has settled over the lost golden age of Cambodian cinema: “They are the living memory of that cinema” (Chou, Sommeil 13).

This programmatic opening clearly alludes to the role that cinephiles and their memories have played in France—for example, in the recovery of Georges Méliès’ oeuvre—and suggests that cinephilia might now play a similar role in Cambodia. In an interview included in the DVD’s bonus material, Chou also claims that the opening scene of his film recreates a personal experience: “Though he did not speak Khmer at the time […], he recalls instinctively understanding at a certain point that his companions were talking about Cambodian film” (qtd. in Barnes 80). By telling and staging this “cinephiliac anecdote”, Chou emphasises that the key to Cambodia for him was cinema (Keathley 151). At the same time, he again refers to the tradition of French cinephilia, since the practice of inventing such anecdotes and disseminating them through films or paratexts like interviews and writings was common among the French New Wave (Frisch 233). From the first minute of his film, Chou thus marks French cinephilia as one of the lenses through which he encounters his material. This may explain why Leslie Barnes has difficulty grasping Golden Slumbers with the typology Hamid Naficy proposes in his writings on exilic and diasporic filmmaking: “Chou’s film is not easily situated within Naficy’s rubric […]. It […] implicitly asks how one ‘returns’ to a country, culture, or language that is not one’s own” (91). In fact, Chou approaches Cambodia through a lost film heritage that, as the grandson of a film producer, is his own in that the memory of it is part of his family history. (This is evident, for example, in the photographs on display in his aunt’s flat, see below.) To convey this approach artistically, Chou in turn refers to an audiovisual culture and language he made his own through his cinephiliac self-study in France. In Golden Slumbers, the trope of “return”, so elementary to exilic and diasporic filmmaking, is thus premediated by French cinephilia and its fascination for moving image memory.

Cinephilia as Mediator

After the opening sequence, Chou begins his investigation in Paris by asking his aunt Sohong Stehlin, daughter of the producer Van Chann: “What do you remember?” While Stehlin shares her memories of the early 1970s, black-and-white family portraits are shown in her apartment, followed by photographs taken during the filming of her father’s productions. When asked what remains, Stehlin responds:

You can still find some songs. […] During the four years of Pol Pot, everyone sang. Whenever we could, we sang. We did it secretly, quietly, but we sang. Today almost all the films are gone but the songs remain. And even the young people now in Cambodia, all the young singers cover the old songs. In karaokes all you hear are old songs. […] You can […] listen to the songs, and recall those memories.

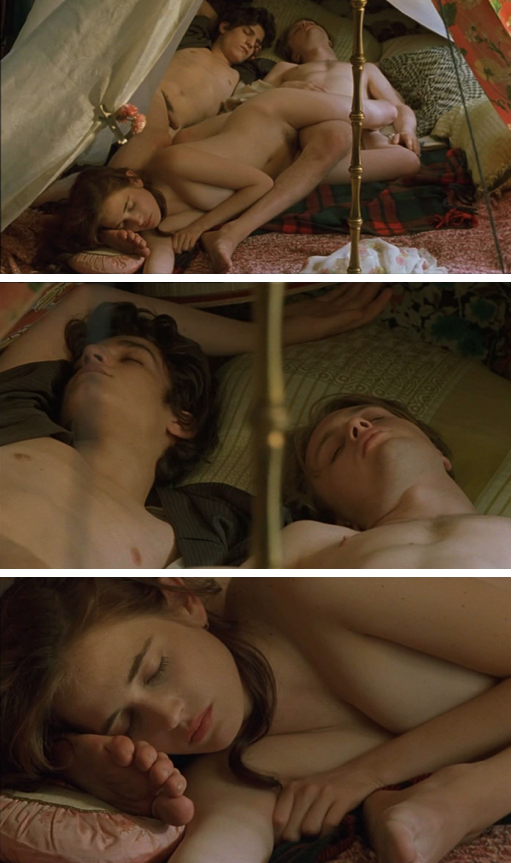

However, only survivors can actually “recall those memories”. For the older generation, the songs are a reminder of happy times and of the resistance against Pol Pot’s dictatorship. For the younger generation, they are merely karaoke tunes. But they are still heard and sung, for example in the former Bokor cinema, which is now a karaoke bar. As Stehlin continues to speak, a song from a Van Chann production plays, while websites and channels about the lost films and their songs are shown on a computer screen. After a brief fade to black, the film then continues in Phnom Penh, where in the semi-darkness five young people lie intertwined, sleeping, dreaming (Figures 2–4).

Figure 2: Sleeping members of the Kon Khmer Koun Khmer collective. Golden Slumbers.

Vycky Films/Bophana Production/Araucania Films, 2012. Screenshot.

Figures 3–4: Sleeping members of the Kon Khmer Koun Khmer collective. Golden Slumbers.

Vycky Films/Bophana Production/Araucania Films, 2012. Screenshots.

For cinephiles, these images, though not nearly as sexualised, may recall the film-loving youths in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003) (Figures 9–7). Do these young Cambodians perhaps share a similar passion for cinema? (The three protagonists in Bertolucci’s film meet at the protests against the dismissal of Henri Langlois as director of the Cinémathèque française in February 1968.) And if so, what awareness, what activism is possible once they awaken from their slumber?[8]

Figures 5–7: Isabelle (Eva Green), Théo (Louis Garrel) and Matthew (Michael Pitt) sleeping in a tent. The Dreamers. Recorded Picture Company/Peninsula Films, 2003. Screenshots.

As already hinted at by Sohong Stehlin, there is both continuity and disruption between Cambodia’s still dormant young cinephiles and those who survived the Khmer Rouge. The former actress Dy Saveth, for example, is now a dance and singing teacher for young Cambodians, whom she receives in a room covered with old photographs and newspaper clippings. The setting of her room vaguely recalls François Truffaut’s The Green Room (La Chambre verte, 1978), whose protagonist, played by the director himself, builds a private chapel to preserve the memory of deceased artists. But Dy Saveth seems to know that her memory work can only bear fruit if she shares it with the younger generation. Therefore, she not only tells her story, but also trains young Cambodians to sing, for example, songs by Sinn Sisamouth, who disappeared under the Khmer Rouge. In similar fashion, Li Bun Yim, Yvon Hem and Ly You Sreang share memories of their lost films and explain their creative strategies. Here too, Golden Slumbers shows continuity and disruption. For instance, while Ly You Sreang recounts the filming of a scene from his The Sacred Pond (Tro Peang Peay, 1970), we see the shooting location, a now heavily algae-covered pond; a shoe and a leaf are floating in the water. This image resonates with Ly You Sreang’s description of the original scene, in which the bathing protagonist’s clothes were stolen so that he had to cover himself with a fig leaf. As the old filmmaker continues to speak, young members of the Kon Khmer Koun Khmer collective begin to reimagine the scene—but we only see the filming and not the actual re-enactment. Instead of restoratively “recreating” what has been lost, Golden Slumbers thus takes a reflective approach, suggesting that, even as younger generations of cinephiles commit to continuing the memory work, there must be room for innovation.

Certainly, Chou’s desire to inscribe the collective’s and his own cinematographic memory work on the Cambodian film heritage into the collective visual memory of (French) cinephilia could also limit such artistic freedom. But instead of staging himself as a cinephile, as François Truffaut did, for example, Chou does not appear on screen in the entire film. Thus, Chou by no means follows possible French role models à la lettre. Instead, he adopts strategies more familiar from, for example, Rithy Panh’s documentaries on the atrocities of the Khmer rouge, such as interviewing eyewitnesses at the original site.[9] Although Golden Slumbers begins with Chou’s family biography and can certainly be understood as a personal response to Cambodia’s traumatic past and the pleas of its survivors, it thus remains open where exactly Chou positions himself: does he see himself as part of Cambodia’s young generation? Does he, as the grandson of a producer, speak for, or with, the old generation? Or does he, as the descendant of Cambodian emigrants, speak for the (French) diaspora? While some of the cinephiliac references in Golden Slumbers might mark Chou’s position as that of a cultural outsider, they also have the potential to draw the attention of other cinephiles to the fragile situation of Cambodia’s film heritage.[10] For example, the subtle reference to The Dreamers recalls a “history of cinephilia” more familiar to French or Western audiences, thus linking the loss of film heritage in Cambodia to a scenario (the brief dismissal of Henri Langlois as director of the Cinémathèque française) that exemplifies the importance of a film heritage that is preserved, accessible and not instrumentalised by the state. Cinephilia thus serves as a mediator not only between different generations, but also between different times, places, cultures, and audiences.Appropriating and Remediating a Cinephiliac Classic

As we already saw for the scene from The Sacred Pond and its re-enactment, Golden Slumbers often relies on associative montage to make visible what remains and open up spaces for new connections. A number of scenes filmed in the former Hemakcheat Cinema, which is now a slum, provide particularly striking examples. The first and longest scene in the Hemakcheat is introduced by filmmaker Ly Bun Yim who narrates the plot of his film Khmer after Angkor (Orn Euy Srey Orn, 1972) and begins to sing one of its songs. Meanwhile, we see a tall, bright building with a flowering shrub growing from its roof: the Hemakcheat cinema, as a text insert reveals. A recording of the song from Khmer after Angkor now begins to play, and light falls through the windows, just as the lights of the projector once fell through the windows of the projection booth. But where the screen once hung, there is now a bare brick wall against which the remains of cinema seats can only be inferred. While Li Bun Yim’s stories and additional text inserts reveal the former splendour of the Hemakcheat, we see its now dilapidated and filthy interior along with the modest dwellings of those who found shelter there. The song from Khmer after Angkor is overlaid with voices, sirens, pattering rain and squeaking bats; children stare at television screens; rain penetrates the ruined façade; a woman prepares a meagre meal. And yet even here, memories of the lost film heritage are still alive, as demonstrated by two men who recall their parents telling them about films, and an elderly woman holding a child, recounting the tragic story of Tea Lim Koun’s Out of the Nest (Peov Chouk Sor, 1967):

The Hemakcheat is haunted by the flickering images of the films once screened there […]. It is also haunted by the actors, technicians, film-makers, and films lost during the Khmer rouge period, as well as by the ghosts, traumatic memories, and struggles to survive that its new occupants carry with them. (Barnes 88)

The same ghostly atmosphere dominates the second scene inside the ruin. Here, the montage gives the impression that the present-day inhabitants of the Hemakcheat are listening to a tragic dialogue from Ros Proeung’s The Sad Life (Chivith Aphorb, 1973) and shedding secret tears, just as audiences once did at this very spot. Again, Chou shows the rays of light and the silent screen. A revival of the lost golden era seems within reach and yet impossible. Only in the third and last scene in the Hemakcheat, which is also the final scene of Golden Slumbers, does the screen come back to life. A handful of preserved moving images flicker across the bare wall, their colours and textures overlapping with those of the bricks. It is thus not really a return, but rather an inspiring glimpse of former glory—as if to highlight the possibilities that lie dormant in a reflective and creative preservation and transmission of Cambodia’s lost film heritage, rather than recreating it. And it is certainly no coincidence that Chou once again refers to the younger generation at this point: the members of his collective, who were still dreaming at the beginning, have awakened.[11] They stand in the Hemakcheat and gaze in wonder at the revived screen, where the audience can join them in watching a short scene from an unnamed film (the only one in which image and sound are seen together). Only then does Golden Slumbers end with a memorial to the filmmakers murdered under the Khmer Rouge.

Once again, however, Golden Slumbers goes beyond the context of Cambodia and ties into the collective visual memory of cinephilia, inviting comparison, for example, with the ruins of Nuovo Cinema Paradisoin Giuseppe Tornatore’s film of the same name (1989): here, too, a return takes place when the protagonist Salvatore (Jacques Perrin), a celebrated filmmaker, revisits his native southern Italian village for the first time after years of exile in Rome. The old cinema where he learned the craft of film projection as a boy is soon to be demolished; melancholically, he strolls through the dilapidated building and climbs up into the projection booth one last time. Like the Hemakcheat in Golden Slumbers, the Paradiso is a ruin, the interior dusty and covered with cobwebs, remnants of cinema seats still lying on the floor. But a closer look reveals a significant difference: in Cinema Paradiso, the screen is torn and there is no light left on it. While the Hemakcheat is still inhabited in the truest sense of the word, the Paradiso has been permanently abandoned. By watching the ruin collapse, Salvatore completes what his mentor, the old projectionist, had asked of him: to leave and forget, to look forward and not back. In contrast, Golden Slumbers seems to suggest that Cambodia’s younger generation, perhaps including the “returning” director himself, can only move forward by taking a step back, by confronting the country’s traumatic past and creatively engaging with what remains of its cultural heritage. In this way, Chou not only alludes to the motif of the cinema ruin, made famous by Tornatore’s Oscar-winning classic, but also remediates it. He repurposes the motif to fit his Cambodian context, giving it thus a completely new message. While in Tornatore’s film the cinema ruin nostalgically symbolises the end of an era from which we have to say goodbye in order to move forward, in Chou’s film it is more of a starting point, a site of memory, and a burial ground full of inspiring relics and perhaps as yet untold stories.

Figure 8 (above): Ghostly projection lights fall into the ruin of the Hemakcheat Cinema in Phnom Penh.

Golden Slumbers. Vycky Films/Bophana Production/Araucania Films, 2012.

Figure 9 (below): Salvatore (Jacques Perrin) in the ruins of the Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, the torn screen in the background. Cinema Paradiso. Les Films Ariane, 1989. Screenshots.

Conclusion: Cinephilia and Multidirectional Moving Image MemoryUsing Davy Chou’s Golden Slumbers as an example, this article has demonstrated how creative approaches to film heritage, including documentaries, can contribute to a productive engagement with losses that are often severe in this particular field of cultural heritage. This makes such engagements an important part of larger processes of both moving image memory and cultural memory more generally. As the example has shown, even documentaries that deal with such processes are subject to premediation in the form of artistic influences or cultural lenses. Despite a “supposedly indexical reference to ‘reality’”, they are not mere documentations of threatened or lost cases of film heritage (Brunow 5). Rather, like feature films, they confront us with “fantasies of the past determined by needs of the present”, which sometimes even have “a direct impact on realities of the future” (Boym XVI). Through their narrative strategies and aesthetic devices, but also through their circulation and reception, documentaries about film heritage can enable local cases to enter new, global communities of memory that transcend their respective spatial, temporal and cultural contexts. As dynamic interfaces between film heritage and moving image memory, documentaries like Golden Slumbers thus assume an important function. They contribute to the fact that even lost films, in the sense of Aleida Assmann’s functional memory, can still be related to the present.

In Golden Slumbers, the French-Cambodian filmmaker Davy Chou draws on the French tradition of cinephilia as a cinematographic memory culture. This lens (pre)mediates his post-migratory “return” to Cambodia and shapes the images and sounds with which he conveys the continuing presence of Cambodia’s lost film heritage. Cinephilia, then, serves to express a liminal position between France and Cambodia, between the legacy of Chou’s grandfather, the producer Vann Chan, and his own filmmaking, as well as between the French New Wave and Cambodian documentary in the style of Rithy Panh. References to cinephiliac classics like The Dreamers or Cinema Paradiso help make Golden Slumbers accessible to cinephiles worldwide and raise awareness of the fragile situation of Cambodian film heritage. Finally, by repurposing and transforming these references, Chou also contributes to a multidirectional remediation of cinephilia and its collective visual memory.

However, constant remediation does not necessarily amount to actualisation and diversification. It may also contribute to “stabilising certain mnemonic contents into powerful sites of memory” (Erll, Memory 143). This raises the question of whether cinephilia, as a cinematographic memory culture, has ever truly “un-Frenched itself”, as Thomas Elsaesser argues (“Cinephilia” 41). Does not the remediation of narrative patterns and representational conventions established in French cinephilia ultimately amount to a “re-Frenching”? Does not a constant remediation of established cinephiliac classics also reproduce and stabilise a Westernised or even colonial gaze?[12] And might not structural factors such as selection criteria for artistic production funding or film festivals—which for documentaries like Golden Slumbers “occupy nodal roles in both instances, as gatekeepers and as tastemakers”—reinforce such restorative tendencies (De Valck 109)?

At the same time, film festivals and other institutions that gather audiences are not only nodes of distribution or taste-making. Since each audience brings its own set of memories to the films, film festivals, cinematheques, museums etc. are also “nœuds de mémoire” (Rothberg, “Introduction” 7–9); that is, nodes of cultural and moving image memory. For “sites of memory do not remember by themselves—they require the active agency of individuals” (8). Individual as well as collective engagement with films like Golden Slumbers, as it takes place on such occasions, could therefore just as well favour reflective tendencies, as they are also inherent in cinephilia as a moving-image memory culture. Future studies should therefore consider audiences, their backgrounds and their reception contexts much more than was possible in this short article. Only in this way can we succeed in developing analytical models that do justice to the complex multidirectionality of moving image memory.

Notes

[1] New Cinema History focuses on the social and cultural history of cinema. Its subjects include the exhibition, circulation and consumption of films, local and regional film and cinema cultures, as well as audiences and their habits of moviegoing (for a detailed introduction to New Cinema History, see Maltby; Biltereyst, Maltby, and Meers). Of particular note in the context of this article are Annette Kuhn’s works on cinema and memory, including An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory on moviegoing in 1930s Britain and a special edition of the Memory Studies Journal Kuhn co-edited with Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers.[2] Astrid Erll uses the term “premediation” to refer to the fact that “existing media which circulate in a given society provide schemata for future experience” (Erll, “Literature” 392). With “remediation”, she refers to “the fact that memorable events are usually represented again and again, over decades and centuries, in different media” (392).

[1] In an interview, Chou claims: “I didn’t study cinema, I’m self-taught. I made my own cinephilia in Lyon, where I grew up. It was a slow discovery, when you open a book called Nouvelle Vague…” (my trans.).

[4] The case of Georges Méliès occupies a key role in the French tradition of cinephilia. It has inspired several films, including the short documentary Le Grand Méliès (1952) by Georges Franju, who cofounded the Cinémathèque française with Henri Langlois, and Martin Scorsese’s family-friendly feature in 3D, Hugo (2011).

[5] Aleida Assmann understands a canon as “marked by three qualities: selection, value, and duration” (100). For something to become canonical, a selection process must take place through which a text, etc., is distinguished from others and given a certain value. This value is then reaffirmed through “repeated presentation and reception which ensures its aura” and makes canonisation permanent (101).

[6] In film restoration, there is a fine line between reconstruction based on reliable sources and recreation, which Paolo Cherchi Usai describes as an “imaginary account of what the film would have been” (67).

[7] Kon Khmer Koun Khmer (Khmer Films, Khmer Generations) is a collective founded by Davy Chou in 2009. It consists of around sixty young members who are working in various ways (e.g., through films, exhibitions and festivals) to keep the memory of the lost Cambodian film heritage alive.

[8] Bertolucci’s protagonists are awakened by a cobblestone smashing the window. They then join the incipient protests of May 1968.

[9] Chou himself names other role models outside the French New Wave, including, for example, Jia Zhangke (Sommeil 7).

[10] Golden Slumbers celebrated its world premiere at the Berlinale and was then shown at over twenty international festivals worldwide. The attention thus generated has contributed, among other things, to the fact that some Cambodian films, which were in poor condition but had been preserved, have now been professionally restored and digitised.

[11] In the meantime, several members of Kon Khmer Koun Khmer have made a name for themselves internationally with their own films.

[12] The question of possible connections between (French) cinephilia and the construction or reproduction of colonial gazes and structures in the field of film heritage is one of the main concerns of my dissertation project on “Cinephilia(s) Revisited: Movies – Memory – Mobilisation” (University of Marburg, Germany, & Université de Lorraine, France; working title). It is further deepened there through investigations into practices of (re)programming, digitisation and re-editioning.

References

1. Assmann, Aleida. “Canon and Archive.” Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, De Gruyter, 2008, pp. 97–108.

2. Barnes, Leslie. “Un cinéma sans image: Palimpsestic Memory and the Lost History of Cambodian Film.” Post-Migratory Cultures in Postcolonial France, edited by Kathryn A. Kleppinger and Laura Reeck, Liverpool UP, 2018, pp. 79–95, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv3hvc45.9.

3. Biltereyst, Daniel, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers. “Introduction: The Scope of New Cinema History.” The Routledge Companion to New Cinema History, ed. by Daniel Biltereyst, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers, Routledge, 2019, pp. 1–12.

4. Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. Basic Books, 2001.

5. Brunow, Dagmar. Remediating Transcultural Memory: Documentary Filmmaking as Archival Intervention. De Gruyter, 2015, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110436372.

6. Cherchi Usai, Paolo. Silent Cinema: An Introduction. BFI, 2000.

7. Chou, Davy. Le Sommeil d’or: Un Film de Davy Chou. Press kit, Bodega Films, www.bodegafilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/dp_le_sommeil_d_or1361965114.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

8. ---. Interview by Yann Pichot, MANIFESTO.XXI, 6 Jan. 2017, manifesto-21.com/diamond-island.

9. Cinema Paradiso [Nuovo Cinema Paradiso]. Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore, Les Films Ariane, 1989.

10. Cowan, Michael. “Learning to Love the Movies: Puzzles, Participation, and Cinephilia in Interwar European Film Magazines.” Film History, vol. 27, no. 4, 2015, pp. 1–45, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2979/filmhistory.27.4.1.

11. De Valck, Marijke. “Fostering Art, Adding Value, Cultivating Taste: Film Festivals as Sites of Cultural Legitimization.” Film Festivals: History, Theory, Methods, Practice, edited by Marijke de Valck, Brian Kredell, and Skadi Loist, Routledge, 2016, pp. 100–16.

12. De Valck, Marijke, and Malte Hagener, editors. Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam UP, 2005, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3685.

13. The Dreamers. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, Peninsula Films, 2003.

14. Elsaesser, Thomas. “Über den Nutzen der Enttäuschung: Filmkritik zwischen Cinephilie und Nekrophilie.” Filmkritik heute: Bestandsaufnahmen und Perspektiven, edited by Irmbert Schenk, Schüren, 1998, pp. 91–114.

15. ---. “Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment.” Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, edited by Marijke de Valck and Malte Hagener, Amsterdam UP, 2005, pp. 27–44, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988.

16. Erll, Astrid. “Literature, Film, and the Mediality of Cultural Memory.” Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, De Gruyter, 2008, pp. 389–98.

17. ---. Memory in Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230321670.

18. Ezra, Elizabeth. Georges Méliès. Manchester UP, 2000.

19. The Forbidden Reel. Directed by Ariel Nasr, Loaded Pictures/National Film Board of Canada, 2019.

20. Frick, Caroline. Saving Cinema: The Politics of Preservation. Oxford UP, 2011.

21. Frisch, Simon. Mythos Nouvelle Vague: Wie das Kino in Frankreich neu erfunden wurde. Schüren, 2007.

22. Gauthier, Christophe. La Passion du cinéma. Cinéphiles, ciné-clubs et salles spécialisées à Paris de 1920 à 1929. Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma/École nationale des chartes, 1999.

23. Golden Slumbers [Le Sommeil d’or]. Directed by Davy Chou, Vycky Films/Bophana Production/Araucania Films, 2011.

24. Le Grand Méliès. Directed by Georges Franju, Armor Films, 1952.

25. The Green Room [La Chambre verte]. Directed by François Truffaut, Les Films du Carrosse/Les Productions Artistes Associés, 1978.26. Halbwachs, Maurice. Les Cadres sociaux de la mémoire.Alcan, 1925.

27. Hugo. Directed by Martin Scorsese, GK Films/Infinitum Nihil, 2011.

28. International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). “Don’t Throw Film Away: The 70th Anniversary FIAF Manifesto.” FIAF, www.fiafnet.org/pages/Community/FIAF-Manifesto.html. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

29. Keathley, Christian. Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in the Trees. Indiana UP, 2006.

30. Keller, Sarah. Anxious Cinephilia: Pleasure and Peril at the Movies. Columbia UP, 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/kell18086.

31. Khmer after Angkor [Orn Euy Srey Orn]. Directed by Ly Bun Yim, Runteas Pich Production, 1972.

32. Kon Khmer Koun Khmer. “About Us.” KonKhmerKounKhmer, konkhmerkounkhmer.wordpress.com/about. Accessed 18 Oct. 2020.

33. Krämer, Marie. “Cinéphilie als Film(vermittlung) im Film: François Truffaut’s La Nuit américaine (1973)”. ffk journal, no. 4, 24019, pp. 98–113, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3708.

34. Kuhn, Annette. An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory.I. B. Tauris, 2002.

35. Kuhn, Annette, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers. “Memories of Cinemagoing and Film Experience: An Introduction.” Memory Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, 2017, pp. 3–16, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016670783.

36. Le Grand Méliès. Directed by Georges Franju, Armor Films, 1952.

37. Maltby, Richard. “New Cinema Histories.” Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies, ed. by Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers, Wiley Blackwell 2011, pp. 3–40.

38. Martin, Adrian. “Cinephilia as War Machine.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, vol. 50, no. 1/2, 2009, pp. 221–25, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/frm.0.0044.

39. Naficy, Hamed. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton UP, 2001, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv346qqt.

40. Out of the Nest [Peov Chouk Sor]. Directed by Tea Lim Koun, Dararoath Films, 1967.

41. Remake Remix Rip-Off. About Copy Culture & Turkish Pop Cinema. Directed by Cem Kaya,UFA Fiction, 2014.

42. Rothberg, Michael. “Introduction: Between Memory and Memory: From Lieux de mémoire to Nœuds de mémoire.” Yale French Studies, no. 118/119, 2010, pp. 3–12.

43. ---. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford UP, 2009, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804783330.

44. The Sacred Pond [Tro Peang Peay].Directed by Ly You Sreang, production company unknown, 1970.

45. The Sad Life [Chivith Aphorb]. Directed by Ros Proeung, production company unknown, 1973.

46. Talking about Trees. Directed by Suhaib Gasmelbari, Agat Films & Cie, 2019.

47. Willemen, Paul. “Through the Glass Darkly: Cinephilia Reconsidered.” Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory, BFI Publishing/Indiana UP, 1993, pp. 223–57.

Suggested Citation

Krämer, Marie. “In Search of a Lost Cinema: Cinephilia and Multidirectional Moving Image Memory in Golden Slumbers (Davy Chou, 2012).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 21, 2021, pp. 72–88, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.04.

Marie Krämer holds an MA in Media Studies (Philipps-Universität Marburg) and in Cultural Studies & Education (Université de Lorraine). Building on professional experiences at Berlinale, DOK Leipzig, Cinémathèque de la Ville de Luxembourg and the German Federal Cultural Foundation, she is doing a binational PhD on “Cinephilia(s) Revisited: Movies – Memory – Mobilisation”. Her research explores connections between cinephile films and practices as well as moving image memory and film heritage. At the Institute for Media Studies at the University of Marburg, Marie Krämer also teaches on film heritage, film festivals and curatorial practices in film museums and art galleries.