Modern Routines: The Perception of Time and Space in Film Spectators’ Memories of Cinemagoing in 1940s Buenos Aires

Cecilia Nuria Gil Mariño, Alejandro Kelly-Hopfenblatt, Clara Kriger, Marina Moguillansky, and Sonia Sasiain

Abstract

The renewal of theoretical and methodological tools, putting the spotlight of film historiography on audiences and their movie-going routines, has meant a significant shift for the study of national and regional cinemas. The New Cinema History signalled the importance of introducing in-depth, data-based studies of exhibition, distribution and programming, considering individual and collective experiences. One trend in this renewal of cinema history are studies relying on oral testimonies of the elderly to reconstruct their movie-going practices, contributing also to the methodological reflection on the use of memories as historical sources. This article discusses the ways spatial and temporal perceptions appear in oral narratives of movie-going experiences in Buenos Aires during the 1940s and 50s. Based on twenty qualitative interviews with elderly people, we explore how through their imaginaries they build a certain place in the past that contrasts with the perceived present. We trace the ways in which memories are intertwined with the emergence of modern routines and the way the cinematographic experience affected the audience’s cartography of the different environments of Buenos Aires. Film consumption and its imaginaries allowed the emergence of new sensorial skills related to a changing world.

Dossier

Introduction

The animated short When Magoo Flew (Pete Burness, 1955) presents its iconic protagonist, a short, very near-sighted elderly man, leaving his home to go to the cinema. He passes the door of a movie theatre showing a melodrama, but he doesn’t realise it and continues on his way until he comes to a nearby international airport. The posters advertising Hawaii are very similar to film billboards, so Magoo thinks it’s his lucky day and assumes that a 3D movie is showing. He gets on the plane and, happy with his experience, announces in a cheerful tone to the person in the seat next to him that this is his first 3D movie and also his first flight. When the lights go out and the plane takes off, we see him totally exalted, shouting “3D is extraordinary! You can actually feel the plane taking off!”

How to understand such a direct connection between the movie theatre and an aeroplane flight? The connection between the expectations and sensations aroused by journeys and films takes us to the experience of the disembedding of modernity (Giddens), closely associated with the emergence of new means of transport and communication, which all at once connect space and broaden our imaginary worlds. Films gave audiences, whether domestic or foreign, a reflexive sensory horizon that connected directly with the experience of modernisation and modernity (Hansen). In this experience of disembedding that associates—among other things—cinema and technology, classic Hollywood film holds a privileged place, dominant in almost all world markets since 1920. It is not just a question of films that promoted the benefits of the new technologies; classic cinema made it possible to embody the modern atmosphere with its rhythms, its logics, and its pleasures, which came as an unsettling shock.

The vernacular modernity of classic cinema, as Hansen writes, allowed spectators from remote points of the planet to participate in a shared experience. Just by sitting in a cinema seat they could fly to exotic places or travel in time to the past and the future, no matter where they were. Within this universe, the film-going audience of Buenos Aires, with a notable cinephilia and a marked thirst for culture, experienced a cultural expansion inside picture palaces that allowed them to give meaning to the transformations they experienced in their everyday lives.

In this article we explore the experience of cinema audiences in Buenos Aires in the 1940s, combining the approach of the new history of cinema (Allen and Gomery; Maltby, Biltereyst and Meers) with contributions to the sociology of culture (Giddens; Thompson; Appadurai). In particular, we use the oral history methodology, paying special attention to the perception of space and time in subjects’ memories. In the first section we present some conceptual lines and describe the methodological design, while in the second and third sections we approach through the oral history testimonies the experience of spectators in terms of the space-time of the cinema in the city. In the conclusions we offer a general reflection, raising some new research questions.

History, Memory and Film Spectators

The new history of cinema is characterised by taking the focus off the films and incorporating the institutional, social and cultural dimensions of consumption and circulation of film (Maltby, Biltereyst, and Meers). In this history of cinema “written from below” (Maltby), we explore the spectators and the materiality of their practices, their forms of involvement, their routines and their representations. One of the key lines within this historiographical renewal has been the investigation into subjects’ cultural memories and how these overlap with the cinema.

Annette Kuhn situates the consumption and reception of film in Britain during the 1930s within historical and ethnographic studies. There she distinguishes cinematic memory as a subtype of cultural memory and asks about the role of time within it. From her perspective, this question has great resonance with the consideration of lived time, the time of the inner life, which is lived both collectively and individually, and is in some ways, incongruent with the linear temporality of historical time. For this, oral histories and the review of archives of memoirs and personal documents have proved to be central tools. In this regard, we follow Daniel James’ proposals, when he stresses that the oral history sets the challenge of understanding the interviewee’s account as a narrative, where what is most important is the construction of meaning rather than factual accuracy, and the account is a public construction marked by class and gender conventions.Studies of cinemagoers’ memories indicate that recollections of the experience of going to the cinema tend to recall the spaces, the company kept and the routines, in the context of a collective account that shows a practice shared with others and therefore closely tied to sociability. As Kuhn states:

The place where memories of cinema in the world and memories of the world in cinema meet provides a useful point of departure for inquiry into the particular meanings of cinemagoing for the 1930s generation, and more generally for a quest for insight into the relationship between cinema memory and cultural memory in their organization of place, time and the body. (113)

These works have contributed to reconstructing the geography of cinemas as a relational spatiality, in which some specific movie theatres are connected with certain sociabilities and certain modes of consumption (Allen). Memories about the cinema tend to be “memories of pleasure” as Daniela Treveri Gennari writes, recalling situations connected with joy and happiness, and tending to put forward a past that is better than the present (40). Likewise, in a collective study published in 2020 on the histories and memories of Italian audiences in the second postwar period, Treveri Gennari et al. highlight the importance of cinema as a space of escape for a country emerging from the horrors of war, as well as its pedagogical character. They also propose the concept of “embodied cinema memories” (176) as a way to think about an emotional history of the experience of going to the cinema and its centrality in the culture and memory of postwar Italy.

Complementarily, the sociology of culture perspective allows us to analyse the modernising aspect of cinema and its subjective impact on audiences. As Anthony Giddens writes, modernity is characterised by a process of social change in which time and space become homogeneous, standardised dimensions, permitting the large-scale coordination of human interaction. In terms of the social experience, interactions become disembedded from the immediate context, and social practices and relations are rearticulated around the institutions of modernity. The development of the media favours the pre-eminence of a broadened interaction no longer limited to copresence; cinema in particular is a media technology that enables a “media near-interaction” that implies a relation of non-reciprocated intimacy from a distance. So it is that audiences can build ties with movie stars who “become familiar, recognizable figures who are frequently part of individuals’ discussion of everyday life” (Thompson 285). Along similar lines, Arjum Appadurai stresses the disruptive role of cinema as a source for the social imagination, associated with the formation of practices and social identities not always congruent with audiences’ sociopolitical context of belonging. In this respect, cinema gave access to plots, characters, narratives and scenarios that allowed spectators to broaden the repertoire for the imaginary development of possible lives.In the 1940s, film was the dominant form of entertainment, the one most consumed by the population of Buenos Aires. There were around two hundred cinemas in the city, including the picture palaces in the centre, where new films were premiered, and the more modest neighbourhood cinema circuits, which showed the same titles a few weeks later. Cinema tickets were relatively affordable, so middle-class families could afford to go frequently, about once or twice a week.

This central space that cinema held in the dynamics of 1940s Buenos Aires has barely been considered, and has been limited to footnotes in research into the social and cultural history of the city. At the same time, the history of Argentine cinema has rarely concerned itself with the experience of the audiences and the film culture that developed. Given this background, in 2017 we began a research project dedicated to the history of cinema audiences in Buenos Aires, focusing on reconstructing the social and cultural experience of going to the pictures. Along with a reconstruction of the films on offer and a cartography of the cinemas from this period, we started to compile the memories of those who were cinema spectators in the city of Buenos Aires in the 1940s, through interviews and by tracking down written memoirs.

In this article, we base ourselves on a set of twenty-one in-depth interviews, held between 2017 and 2020, with respondents born between 1924 and 1941, who were cinema goers in the city of Buenos Aires during the 1940s. The theoretical sample was made by searching for the greatest variability in terms of social origin. The interviewees were contacted by using different strategies such as visits to nursing homes and retirement homes, or consultations among contacts of the research team, following the snowball method. Of this group, fourteen interviews were with women and seven with men. Their social origins are varied, including people from poor backgrounds, from working-class backgrounds, but also some middle-class subjects, professionals and/or service sector employees. The interview script consisted of a list of open questions regarding their first memories of going to the cinema, routines associated with cinema, the cinemas they went to, the type of films they watched, actors and celebrities, the reading of cinema magazines. At the same time, the conversation was kept open and intended to respect the flux of the memories of the interviewees. The encounters would typically have a minimum extension of one hour and maximum of two. The interviews were videotaped and afterwards the sound was integrally transcribed. The transcriptions were fully coded and analysed using the software ATLAS.ti. In the first stage of the analysis, we used an open-coding approach, following the emergent themes and categories, paying attention to the expressions and working used by the subjects; in the second stage, we performed an axial coding of the transcriptions with a book code that allowed us to capture the routines of cinemagoing and to compare different experiences.

“A Place to Escape from the Monotonous Routine of Everyday Life”

One first aspect to highlight in the configuration of the world that the interviewees recreate in relation to going to the cinema is the temporal dimension as organiser of the experience and their memories. In this sense, we see how cinema memories are based in narratives that recreate different relations of this practice with time: cinema forms part of the first childhood memories; it is located in a specific time, on certain days and times of the week (which in turn are connected with the organisational logics of the cinema sector); it appears as a novel leisure time experience, allowing them to imagine other lives, in another time and space.

Spectators locate their first memories of going to the cinema in their childhood, accompanied by their families. That first experience of going to the cinema tends to be placed at the age of around four or five, with a certain affection (although they are not always happy memories); here the first impressions of the silver screen appear, in the company of their parents. What is remembered from those first outings to the cinema focus in general on the experience itself, on the organisation of the event or on the space of the cinema, more than on the films. For example, Jorge, born in 1939, remembers:

I went to the cinema from a young age, I couldn’t tell you the exact age, but I’d go with my dad and my mum, who also liked the cinema. There was one cinema, El Cabildo, which was next to El Príncipe, where they showed children’s films on Wednesdays, early in the afternoon, and obviously we were there every Wednesday watching films for kids. (Leguizamon)

Childhood memories of the cinema sometimes take on a nostalgic tone, as Kuhn notes, related to the memory of an affective stage left behind. For example, Ángela, born in 1935, says: “I don’t remember much, but I know that I came out of the cinema happy. I had a happy childhood but I don’t remember. I know I was happy; imagine, I’d go to the cinema and I’d decide what outfit to wear, and I know I was happy when I came out of the cinema” (Pardo). In these memories, located in the distant past, there often appears a contrast with the perception of contemporary life and a certain ambivalence towards changes.

Although cinema outings are not always remembered in detail, the interviewees can place the cinema accurately in terms of days of the week and certain times: Tuesday was “ladies’ day,” and for men it was Wednesday. The Sunday matinee is usually mentioned with variety acts, and a feature film that tended to include two episodes from a twelve-part series, obliging them to go every week so as not to miss any. Most of the men remember frequent outings to neighbourhood cinemas, accompanied by their friends, to watch Westerns and adventure films.

For women, ladies’ day was “a key space of female sociability, because it allowed them to experience that social activity without guardians, that is, it was presented as a moment with the greatest degree of social permissiveness” (Conde 8). On those special days, intended for women and children, romantic and melodramatic films were screened. As Kuhn notes, those days were configured as a space of freedom for women, when they could leave their homes and be in a public space:

In essence, they are stories about individuation, about exploring the world outside home and family. They are about becoming a separate person, about asserting a measure of independence, using the safe “transitional” space of the local picture house to do so. (108)

Going to the pictures took on a differentiated nature when it came to weekend outings, which were special: people went to the cinemas in the city centre, in formal attire. In the interviewees’ testimonies we observed a distinction between the experience of going to the cinema in an elegant movie theatre in the city centre, and the more everyday outing to the neighbourhood cinema. So it is that people remember the premieres and the fashionable films that could be seen in city centre cinemas, or an outing that stood out for the décor and the comfort that contrasted with most neighbourhood cinemas. Access to these spaces was experienced as an event, because it implied travelling by public transport and paying a more expensive entrance price than in other cinemas. These questions are also related to the testimonies of interviewees who recalled the need to have certain clothes to go to the cinema and of the distinction that they considered it necessary to dress up for the most important cinemas in the centre: they had to “dress to the nines”, “put on their glad rags” or “show off a new hat”.

In this respect, Manuel Vila from the neighbourhood of Parque Patricios makes a distinction between the family outings to the elegant Cine Teatro Urquiza and going to the pictures with friends, with whom he would go to the Pablo Podestá, a more modest neighbourhood cinema. Another interviewee, Juan Carlos Portas, talked in a similar tone about the revelation of going to the cinema alone for the first time at the age of ten, and how two years later he started to go to cinemas outside of his own neighbourhood.

As we have seen, temporality was organised by the dispositions of the film business. Cinema listings determined how audiences organised their time, fitting in cinema visits with family, school and work routines. But fitting in with cinema times and fitting cinema into one’s own time was perceived as a first act of independence, a step in the process of leaving childhood behind.

In the same way, it is possible to think that the way screenings were scheduled also encouraged a higher frequency of cinema outings. During the period from 1930 to 1944 we observed no fixed day when listings were updated. Given that many people frequently went to the same cinema, during the week the listings varied to satisfy the most devoted cinemagoers. At the same time, the low ticket price allowed for frequent consumption. In a comparative table of the average ticket price for public entertainment in the city of Buenos Aires between 1943 and 1953 Acha shows that the price of cinema tickets was cheaper than other events, including the theatre, the races, football and boxing (Conde 33).

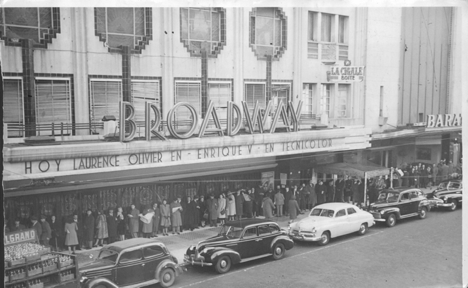

Figure 1: Broadway Cinema, 31/08/1948 (downtown circuit). AGN Departamento Fotográfico.

The cinema was a place “to pass the time” or even where one “wasted time” and played a central role in the organisation of entertainment and of everyday life. Temporality is not thought in relation to the films but the spectatorial act, the place that the cinema occupied in one’s everyday life. With regards to the idea of going to the cinema for the sake of it, Biyina Klappenbach in August 1944 in the newspaper La Nación wrote that “One does not go to the cinema solely to see a film; one goes to the cinema because a routine of modern fashion decrees it.” According to this article, cinema could be considered “a place to escape from the monotonous routine of everyday life.”

The cinema experience took on the double character of rite and routine (Kuhn). The cinema was fundamental in constructing new leisure routines in which the frequency was complemented, paradoxically, with the idea of exceptionality. Memories of these experiences, in the collective imagination, are expressed in certain tropes and assume a formulaic expression (Kuhn). This can be seen, for example, in Mario’s testimony:

Everyone looked forward to Sunday to go to the cinema. I lived in the centre, I knew all the cinemas. Going to the cinema on Sundays was sacred. It was so important for me to go to the cinema that when my father died, I was thirteen, I wanted to do something that would hurt me, to reconcile myself with his death, so I made a pledge to myself not to go to the cinema for a year, and I kept that pledge. I didn’t go to the cinema for a year, when that was the only thing that there was to do. (Telias)

In his memory, Mario highlights the ritual importance and the almost sacred character that going to the cinema held in his life. To not go to the cinema was not only to deprive oneself of entertainment but could also be considered a punishment or penitence.

Furthermore, in relation to the sensation of freedom in going to the cinema, this appears very early in the men’s accounts: at the age of nine or ten, they recall, they could go to the cinema alone or with friends of their age. This independence in cinema outings is remembered as a chance to spend some time without parental supervision, a time used at first for mischief, and then for sexual awakening. Manuel remembers how they would shout at the usher during the film or throw things at the artists performing during the live numbers. Rites of initiation also appear later in his narrative when he comments slyly “at that cinema they showed Westerns, and the forbidden films, too” (Vila).In contrast, the women interviewed recalled that on many cinema outings they were accompanied by their mother, aunt or grandmother. In this respect, Alicia Rodríguez, born in 1941 and a resident of the neighbourhood of Boedo, mentions that she was not allowed to go the cinema alone, “there was always an uncle or aunt, a cousin, someone to go with me.” Nor could she go with her boyfriend without a chaperone. Similarly, Graciela Domínguez Neira, born in 1935 in San Telmo, remembers that she went to the cinema every week with a female friend and her mother, but never alone: “I never went alone, I don’t think I’ve been to the cinema alone in my life. When I met Nicolás, when I was eighteen, then I went to the cinema with him, as a couple, but we had to be home early or they’d come looking for us.”

While for men the freedom of the darkness of the cinema was associated with places they already traditionally occupied in society, for women it was a novelty to be able to move in the public space of the city and, on occasions, this could be experienced as an “escape” or an “adventure”. In this regard, María Simone, born in La Boca in 1935, remembers that, on reaching puberty, her mother allowed her and her sister to attend “alone” the city centre cinemas on weekends.[1] In her account there is a mixture of the fascination with the modern cinemas—“the Ópera had stars on the ceiling”—and female interests, such as the new hats her sister would show off each month. In María’s account, the teen years appear as a period of rebellion when the cinema became a space of incipient freedom. She remembers that on occasions she would play truant from school, evading the inspectors to spend the afternoon with friends in the Carlos Gardel cinema in the neighbourhood of San Telmo.[2]

Women’s role as cinemagoers in Buenos Aires, even with all the reservations and limits imposed on them by a conservative, patriarchal society, opened new spaces of autonomy.[3] What these women represent is the female model of the “new woman” transmitted by the cinema starting in the first decades of the century. In this respect, a chronicle by Biyina Klappenbach in La Nación stated, for example: “Cinema is also fashion. There is everything that is new in women’s fashion: hats, audacious hairdos, dresses, make-up, manners and even male fashions and handsome men.”

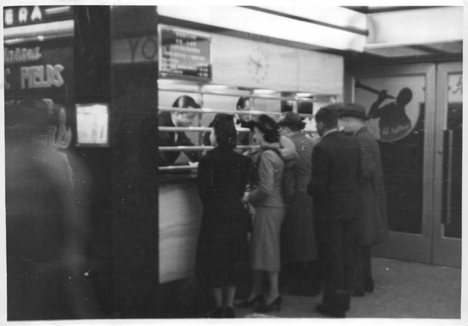

Figure 2: Ópera Cinema-Theatre box office, without date (downtown circuit).

AGN, Departamento Fotográfico.

In women’s memories the cinema was a space to dream and fantasise about romantic films (and lives.) As Alicia says, on “ladies’ days they always showed romantic films, with famous couples” (Rodríguez). For spectators, the cinema was a chance to be transported to another world and imagine romantic lives, a space of freedom where they could dream. But when the show was over, the mechanisms of social containment were rapidly reimposed through the family institution: women hardly ever went to the cinema alone, in the sense that they were considered family outings, and in any case, they had to return home and keep to the established times, or a family member would go and fetch them.

Given the critical views of the period, these distinctions are made as part of conquests for women’s independence such as being able to spend “all the afternoon in the cinema” on “ladies’ day” at functions that included two or three films and which could last up to six hours. “During the week, ladies’ day was the day when we women went alone, with no problems with the times. We could waste the whole afternoon, because you didn’t watch just one film, generally there were two or three,” remembers Alicia. The idea of “wasting time” that appears in the account stresses the autonomy in the use of time in the context of a routine marked by domestic chores and the gender division of labour.Similarly, many of the memories emphasise the nature of initiation of a sexual imaginary for women as well. It is necessary to return here to what we said initially about the nature of the account in these testimonies, and consider the embarrassment many interviewees will feel even today in speaking publicly about this. In this sense, Ana’s testimony is remarkable, as she recalls the practice of “rascar” (“scratching”) in the cinema, where there could be kisses, but normally it was the young man who would place his hand on the girl’s leg and she would feel a tingling in her stomach. She recalls that she and her friends dreamed of sleeping with someone but that they didn’t dare. And so they would talk about “not just what happened in the cinema but also about our longing for things to happen” (Auschlender).

Thus, the cinema configured a universe that influenced the social and private organisation of times, not only in everyday life but also in the stages of each individual life. Its impact was thus not reduced to the time when the film was being projected, but ran through their daily experiences and their construction of expectations. At the same time, in the present it continues to be a filter through which their pasts are organised in the testimonies.

“Our Escape in that World of Six Blocks Was the Cinema”

This need to organise everyday experience also makes the spatial dimensions that appear in interviewees’ accounts. Just as Miriam Hansen writes that films allowed global viewers to participate in the sensory sphere of modernity, this experience was more than the act of watching. In the case of Buenos Aires, the city was in a state of flux, where the urban and social map was being reconfigured and the explosion of the everyday experience accompanied the expanded world on screen.

By the mid-1930s the city was large and low, with a greater density of buildings in the centre. The expansion of high buildings and cinemas intensified in these years with the expansion of the underground and bus system, which began to circulate in areas not connected by traditional forms of transport.[4] The avenues were widened for constantly increasing automobile traffic. All these changes allowed for a more fluid distribution of advertising and films among diverse circuits of film distribution and exhibition.

Cinemas spread out towards the periphery, following the new hubs of circulation generated by the expansion of the transport network’s routes. Many of these cinemas, located on avenues and streets in commercial areas, were built on the ground floor level of new office and apartment buildings, showing a convergence of cinematographic and real estate interests.[5] Film listings in the newspapers and magazines were organised with these new coordinates in which cinemas acted as magnetic centres (Kuhn) that attracted spectators with the variety on offer.

This experience of an expanded city clearly responded to some dynamics typical to Buenos Aires. One fundamental element here was the centre-neighbourhood dynamic, which incorporated the experience of transport or the popularisation of the automobile. Nilda Clauso, born in 1929, grew up in the Núñez neighbourhood, in the north of the city, which in the 1930s still had unpaved roads. She remembers the cinema outings to Calle Lavalle or the Grand Splendid, one of the picture palaces on Avenida Santa Fe, as an outing by car for all the family, or her father took her and her sisters and then went to pick them up.

Furthermore, the building experience went beyond the city centre, as even in the neighbourhoods there was an internal hierarchy. María Simone in her testimony notes all the time in the neighbourhood of La Boca the difference between the cinemas Olavarría and Dante, the latter showing quality films in a beautiful cinema with a spectacular screen. All of them were in turn moulded by what Edgardo Cozarinsky called the “plebeian palaces”: “In the concept of movie palace, the theatre and all its services had to be designed so that the customer felt that they were a member of an imaginary royalty” (15). These last two interviewees, Nilda and María Simone, agree on how impressed they were with the starred ceiling of the Ópera cinema.[6]

The city of Buenos Aires offered different ways of living these experiences. The inter-class relationship implied a dynamic of its own where there was no one space of belonging. The audiences who travelled from the neighbourhoods to the city downtown cinemas came from different social sectors, especially working and middle class. Kuhn suggests that the cinemas played the role of a hub as they attracted the idea of the crowds flowing together around them, a great multiplicity of audiences, and also a place of plenitude and generosity, of a shared experience.

Buenos Aires presented some aspects that set it apart from other cities in the region, due to what Beatriz Sarlo has called a “mixing culture” in which the children of patrician families lived in tension with the children of immigrations. It is important to stress that, unlike other countries such as Chile, this distinction was not made by segregation, and inside the cinema all those spectators who could afford a ticket mixed together. [7] Thus, the case of Buenos Aires has more similarities with that of Mexico City. Ana Rosas Mantecón’s study on Mexican audiences also points out that for the Golden Age period, although a social hierarchy was maintained between types of movie theatres and within the theatres themselves, there were many spaces of encounter and coexistence that brought to the forefront the multiclass character of cinemagoing.

Figure 3: Ópera Cinema-Theatre, 1947 (downtown circuit). AGN Departamento Fotográfico.

Perhaps, as Luciano de Privitellio indicates, in these spaces political differences were declared suspended and this could explain why urban sociability occurred in them, and “social integration was not imagined from the radical illegitimacy of the other” (147). Likewise, for newcomers to the city—foreign immigrants or internal migrants from the countryside—or the second generation of immigrants, these spaces of interclass sociability, as well as the material characteristics of the movie theatres, collaborated with the forging of aspirational dreams of these Buenos Aires middle sectors.

Figure 4: Audience in front of billboard advertising a Carlos Gardel movie after his death, 17/1935, hall of an unidentified cinema. AGN Departamento Fotográfico.

The construction of the oral history accounts creates a spatialised grid, locating and articulating the accounts in a certain space-time (Allen). Thus, the experiences of teenage freedom and the first cinema outings “alone” are marked by the spatial routes of the city, and those spaces in turn are connected, in the memory, with a certain time in one’s life. The emotions when crossing borders or broadening those spaces where people were accustomed to circulating, how they heard the call of adventure and, like the heroes and heroines of the films they loved, went out to conquer a new vital landscape in which the cinema was tied to those first routes. Juan Carlos recalls that:Our escape in that world of six blocks was the cinema, the Aesca cinema. At that time US film was supreme, we caught on to and believed in those films. After watching a movie like The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, which extolled colonialism, we’d be transformed into soldiers of the foreign legion, really into it. But that affinity curiously changed the day I saw the first Carlos Gardel film. I remember on that outing to the pictures, instead of feeling we were foreign soldiers, we went home singing Gardel’s songs. (Portas).

In this testimony the idea of the temporality of growing up and going to the cinema alone crosses over with the expanded universe that the cinema offered. This can be considered taking into account Kuhn’s retrieval of Michel Foucault’s heterotopia. The world of cinema becomes, in memory, “another world” which is both different from the ordinary and embedded in the everyday. This mixture not only affects spatial memory, but also time becomes a mixture of the “localisable” and the “outside”.

Furthermore, the cinemas became spaces of reference of a broadened transmedia experience, key to the development of the cinema business model with the appearance of sound. This could be seen especially at the entrance to neighbourhood cinema theatres. There one would see passions aroused by the most famous radio theatre actors who went to perform the same show they had broadcast earlier in the city centre studios, now as a “live number”. Between the broadcaster in the centre and the neighbourhood, between the afternoon show “in the ether” and the night-time performance, there was a physical and temporal journey that fiction annulled.

Figure 5: General Roca Cinema, 28/09/1941 (Almagro neighbourhood).

AGN Departamento Fotográfico.

ConclusionsAs it occurred with Mr. Magoo, the interviewees expressed with interjections that the experiences offered by the cinema screen affected their bodies, modified them and drew intense sensations and emotions. It is possible to observe that the life accounts internalised all those sensitive processes. The interviewees recognise the routines that they created in their capacity as spectators and explain the ways those media landscapes transformed the way they felt, their imaginaries, and allowed them to compose scripts of imagined lives, both their own and those of other people living in other places (Appadurai).

In Buenos Aires during the period analysed, the experience of “going to the pictures” is remembered as a space and time of freedom. The audience found in cinemas the chance to experience the modernisation of their environment, whether in palatial cinemas or the more modest ones. In crossing the threshold of these cinemas, whether in the city centre or in the neighbourhoods, spectators remember that they experienced modernisation in the exuberant décor and in the way films transported them to other dimensions, just as they incorporated the performativity of the characters that they would transfer to their everyday space, in new practices or in games, once the show was over.

The outing began with the preparation in the domestic space, the journey on public transport, to recognition with other spectators in the street, around the illuminated marquee, and finally inside the cinema that attracted an ever-growing number of spectators. The public was prepared, out of fun or fashion, to participate in a rite of sociability and to show themselves and be seen in the fashionable dress that modern cinemas demanded. In these carpeted, air-conditioned cinemas, they could give themselves over to the experience of the world offered by the film which, in turn, gave them a conversation topic afterwards when socialising with friends. In Buenos Aires these practices made it possible, according to the memories of the interviewees, to occupy the street, to organise new routes of leisure and enjoy showing themselves as consumers of products of cultural industries as a way of occupying the public space, collaborating with the “mixing culture” of Buenos Aires.

Spectators remember the ritual of going to the pictures as a practice repeated at least once a week, which was incorporated into their daily domestic routines but which nonetheless did not lose its characteristic of a spectacular event. The testimonies of the interviewees show the sensation of autonomy for children and women in going to the cinema. Women’s accounts express a feeling of freedom in a contained space, from the autonomy to waste their time to a space-time for fantasy outside of the social rules of the patriarchy. Both for teenage men and women the cinema also formed part of their first imaginaries of a sexual awakening, whether from the stories on the screen or the fantasies of their companies in the seat next to them.

In 1957, the character of ingenue Ana Castro in La casa del angel (The House of the Angel), directed by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, one of the pioneering milestones of Argentine New Cinema, learns to kiss by watching Rudolph Valentino. This reflexive and self-conscious gesture that mixed nostalgia and a critical perspective of the experience of cinemagoing reenforces our interviewees remembrances of cinema as a liberating practice. A similar stance can be find in the oral histories upon which this article is based on, and studying them further and deeper will provide a more complex and thorough understanding of how cinema became part of Buenos Aires’s modern routines.

Notes

[1] Between the neighbourhood of La Boca and what is considered the city centre there is a distance of about two and a half miles.

[2] Education became mandatory in Argentina in 1884 (Law 1420.) To enforce this law, the government designated inspectors who, among other duties, checked up on children’s and young people’s behaviour during school hours.

[3] “The model of the bourgeois woman in the first phase of modernization [...] kept her shut away to perform her role efficiently. This woman would find her essence in her production—her home and her people—and must avoid any bodily exhibitionism, a hindrance to the aristocratic spirit. For this mentality ‘it is the participation of the woman at a public spectacle that wounds, because, as an exposed object, she always loses value as an individual’ [...] In the late 1880s, Huret saw that [women of a certain sector of Porteño society] ‘in the absence of the husband does not leave the home, or does so only to go to the theatre, or for a walk, or remaining in her home or with her family’” (Ballent and Liernur 509).

[4] By the year 1938, a downtown circuit was established that went as far as Avenida Callao, where the neighbourhood circuit then began. In that year, the city had 164 cinemas, of which 47 were located downtown and the rest in the neighbourhoods.

[5] The expansion of the city began in 1904–1914 with the extension of the transport network, the sale of lots in monthly payments, and increased provision of services and infrastructure. The housing stock grew, constructed by individual efforts, made possible by the processes of upwards social movement and the formation of urban middle- and working-classes. From 1912, what Leandro Gutiérrez and Luis A. Romero call the “city of reform” had begun, a successful process of winning over political citizenship that permitted advances in social citizenship. “The census of 1943 recorded coverage of services in non-housing buildings, but nonetheless is indicative of the extent of the infrastructure in the city: 99 percent of buildings had electricity, 98 percent running water, and 74 percent had public sewers. The paving of streets was the sector that grew the slowest: in 1939, 34 percent of streets were paved, and 7000 blocks remained unpaved” (Ballent 41).

[6] Built in 1936 by theatre impresario Clemente Lococo, who hired the Belgian architect Alberto Bourdon. The cinema is one of the most important examples of Art Deco in the city and at the time had a capacity for 2500 people and the latest technical advances.

[7] For more on the case of Chile, see Iturriaga.

References

1. Allen, Robert C. “The Place of Space in Film Historiography.” TMG. Journal for Media History, vol. 9, no. 2, 2006, pp. 15–27, DOI: http://doi.org/10.18146/tmg.548.

2. Allen, Robert C., and Douglas Gomery. Film History: Theory and Practice. Knopf, 1985.

3. Appadurai, Arjum. Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. U of Minnesota P, 1991.

4. Auschlender, Ana. Interview. Conducted by Clara Kriger, 13 Nov. 2019.

5. Ballent, Anahí. Las huellas de la política. Vivienda, ciudad, peronismo en Buenos Aires, 1943-1955. Universidad de Quilmes/Prometeo 3010, 2005.

6. Ballent, Anahí, and Jorge F. Liernur. La casa y la multitud: Vivienda, política y cultura en la Argentina moderna. Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2014.

7. Burness, Pete, director. When Magoo Flew. UPA, 1955.

8. Clauso, Nilda. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño and Marina Gurman, 11 Oct. 2017.

9. Conde, Mariana I. Martes, día de damas. Mujeres y cine en la Argentina: 1933–1955. PhD thesis, UBA-FCS, 2009.

10. Cozarinsky, Edgardo. Palacios plebeyos. Sudamericana, 2006.

11. De Privitellio, Luciano. Vecinos y ciudadanos. Política y sociedad en la Buenos Aires de entreguerras. Siglo XXI Editores Argentina, 2003.

12. Domínguez Neira, Graciela. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño and Marina Moguillansky, 27 Dec. 2020.

13. Elsaesser, Thomas. “The Camera in the Kitchen. Grete Schütte-Lihotsky and Domestic Modernity.” Practicing Modernity: Female Creativity in the Weimar Republic, edited by Christiane Schönfeld, Königshausen & Neumann, 2006, pp. 27–48.

14. Giddens, Anthony. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford UP, 1990.

15. Gutiérrez, Leandro H., and Luis A. Romero. Sectores populares, cultura y política: Buenos Aires en la entreguerra. Siglo XXI Editores Argentina, 2007.

16. Hansen, Miriam. “The Mass Production of the Senses: Classical Cinema as Vernacular Modernism.” Modernism/Modernity, vol. 6, no. 2, 1999, pp. 59–77.17. Iturriaga, Jorge. La masificación del cine en Chile, 1907–1932. La conflictiva construcción de una cultura plebeya. LOM, 2015.

18. James, Daniel. “Escuchar en medio del frío: La práctica de la historia oral en una comunidad de la industria de la carne argentina.” Doña María: Historia de vida, memoria e identidad política.Manantial, 2004.

19. Klappenbach, Biyina. “Modas de ir al cine.” La Nación, Aug. 1944.General clippings folder, Museo del Cine “Pablo Ducrós Hicken”, Buenos Aires.

20. Kuhn, Annette. “Heterotopia, Heterochronia: place and time in cinema memory.” Screen, vol. 45, no. 22004, pp. 106–14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/45.2.106.

21. Leguizamon, Jorge. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño and Clara Kriger, 13 Jan. 2020.

22. Maltby, Richard. “On the Prospect of Writing Cinema History from Below.” Tidjschrift voor mediageschiedenis, vol. 9, no. 2, 2006, pp. 74–96, DOI: http://doi.org/10.18146/tmg.550.

23. Maltby, Richard, Daniël Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers. Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies. Routledge, 2011.

24. Pardo, Ángela, Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño and Clara Kriger, 13 Jan. 2020.

25. Portas, Juan Carlos. Interview. Conducted by Marina Gurman, 20 Oct. 2018.

26. Rodríguez, Alicia. Interview. Conducted by Sonia Sasiain, 17 Dec. 2019.

27. Rosas Mantecón, Ana. Ir al cine. Antropología de los públicos, la ciudad y las pantallas. Gedisa/UAM, 2017.

28. Sarlo, Beatriz. Una modernidad periférica. Buenos Aires 1920 y 1930. Nueva Visión, 2007.

29. Simone, María. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño, 15 Jan. 2018.

30. Telias, Mario. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño and Clara Kriger, 13 Jan. 2020.

31. Thompson, John, B. Los media y la modernidad. Una teoría de los medios de comunicación. Paidós, 1998.

32. Torre Nilsson, Leopoldo, director. La casa del ángel [The House of the Angel]. Argentina Sono Film, 1957.

33. Treveri Gennari, Daniela. “Understanding the Cinemagoing Experience in Cultural Life: The Role of Oral History and the Formation of ‘Memories of Pleasure’.” Tijdschrift voor Mediageschiedenis, vol. 21, no. 1, 201, pp. 39–53, DOI: http://doi.org/10.18146/2213-7653.2018.337.

34. Treveri Gennari, Daniela, et al. Italian Cinema Audiences. Histories and Memories of Cinemagoing in Post-War Italy. Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

35. Vila, Manuel. Interview. Conducted by Cecilia Gil Mariño, 28 Aug. 2018.

Suggested Citation

Gil Mariño, Cecilia Nuria, et al. “Modern Routines: The Perception of Time and Space in Film Spectators’ Memories of Cinemagoing in 1940s Buenos Aires.” History of Cinemagoing: Archives and Projects Dossier, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 21, 2021, pp. 160–177, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.10

Cecilia Nuria Gil Mariño holds a PhD in History from the Universidad de Buenos Aires. Currently, she is an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at Cologne University. Her research focuses on the history of the connections between Argentine and Brazilian cinema, and gender questions and violence in the Brazilian cinema.

Alejandro Kelly-Hopfenblatt holds a PhD in Art History and Theory from the Universidad de Buenos Aires. He is a professor and researcher at this University. His research focuses on the history of Argentine and Latin American film industries and their international commercial networks.

Clara Kriger holds a PhD in Art History and Theory from the Universidad de Buenos Aires, where she is a professor and the coordinator of the film and audiovisual Area of the Institute of Performing Arts. Her research focuses on the history of Argentine cinema in the classical period.

Marina Moguillansky is PhD in Social Sciences (UBA) and Master of Arts in Cultural Sociology. Currently she is full time researcher at CONICET and professor at the National University of Buenos Aires. Her research focuses on Latin American cinema, spectatorship, film policies and cultural trends.

Sonia Sasiain is PhD in History from the Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Professor and researcher at University of Buenos Aires. Her research focuses on the history of Argentine film audiences and their relationship with the urban space.