Filmgoing or Cinemagoing? The Role of the Film Text within Cinema Memory

Jamie Terrill

Abstract

Drawing upon original ethnographic research of rural Welsh audiences, this article meets a burgeoning trend within cinema history studies of reconsidering the importance that film texts can have in benefitting our understanding of social or cultural past. Arguing a perceived separation between the approaches of the New Film History and New Cinema History, the author highlights the benefits of incorporating text-based foci into his research, prompted by a notable separation between those that recalled the social environment of the cinema and those who discussed films, with little crossover between the two. With a dataset that largely recollects the late-1950s and 60s, these fresh textual considerations prompt modifications to existing scholarship pertaining to Britain’s previous generation of cinema audiences, highlighting a particularity of period that primarily revolves around the emergence of popstars and the teenage subculture. Equally, cultural factors such as a rising sentiment of Welsh nationalism are explored through film centred memories and textual analysis, highlighting the vivid semiotics and structures of Welsh national identity. These nuances of Welsh national identity and strengthened feelings of nationalism from the recollected period are explored through analysis of How Green Was My Valley, a US production, and its somewhat counterintuitive popularity with respondents as a “Welsh” film.

Dossier

Most scholars operating within current film historiography will likely be well versed in, or at least familiar with, the New Film History and New Cinema History movements, perhaps even considering themselves a subscriber to one or the other. In brief, both are products of a turning point within the field of film history, namely Robert Allen and Douglas Gomery’s 1985 call for self-reflection and revisionism within approaches to film historiography. The authors argued that film historians had previously been guilty of approaching a film text or subject as a static object, frozen in time and meaning, assuming “a single, indisputable truth” (iv). Allen and Gomery’s work has remained an integral and influential text in terms of film historiography, with their call for revision having arguably guided the direction of the field for the past thirty years (Drake 142; Bosma 15). This is not to say that all contemporary scholars should follow the arguments of Film History: Theory and Practice to the letter; indeed, the very call for revision and appraisal stands starkly against this. Rather, it is a guiding spirit of the discipline that calls upon us to challenge our methods and approaches. It is perhaps only logical then, that different schools of thought have since emerged, both building upon the revisionism as called for by Allen and Gomery. On one side of a spectrum there is the New Film History, potentially more textual in focus, though still channelling a revisionist desire to look beyond aesthetic and static meaning (Chapman, Glancy and Harper 2–3); whilst on the other is the New Cinema History, with roots that drew inspiration from sociology and a less textual focus in favour of a concern for cinema as a social space of consumption and the experiences of audiences (Maltby 8–9).

I refer to this as a spectrum quite purposefully, as one may consider their particular research, methods and approaches to draw from one or the other in differing quantities. Indeed, it is the purpose of this article to explore the middle ground, drawing on a recent trend, particularly from those who may be considered to be notable New Cinema History figures, in reconsidering the role of the film text within the study of social cinema history. In a 2018 keynote presentation, Daniel Biltereyst has noted that there is “much work” yet to be done on the role of the film text within cinematic experiences and the imaginary power of film on/for audiences, particularly the influence this has on their view of the world outside of the cinema. Similarly, Daniela Treveri Gennari and Sarah Culhane have argued the need for a more “film-centric” analysis within New Cinema History, with the authors having utilised the collection and analysis of film specific artefacts to further their understanding of film exhibition, distribution and local consumption in 1950s Italy (796–7). From the other end of the spectrum, Sue Harper, a coeditor of The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches (Chapman, Glancy, and Harper), has recently sought to remind cinema historians that films carry out “vital” functions for audiences and their memories (Harper 690).

With these comments and arguments in mind, it must be asked whether we have, given our shared methods, approaches and desire to uncover film and cinema’s past, somewhat limited our scope to achieve a fuller understanding of the past by prescribing to one side or the other. Indeed, Annette Kuhn’s An Everyday Magic, and the Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain research project that this work drew upon, has been cited as a pivotal landmark within the development on the New Cinema History (Biltereyst). Yet, Kuhn herself, alongside sociologically and oral-history informed methods of ethnographic data collection, performed a textual analysis of a song and dance sequence from Top Hat as a means of exploring the “quasi-sexual satisfaction” and imaginative spaces that the film’s formal elements of construction created for audiences, whilst adhering to the confines of the Motion Picture Production Code (Everyday 192). Furthermore, she has also presented arguments for how discourse of exhibition space and text coexist and interact within cinema memory talk, via the paradigms of “cinema in the world” and “the world in the cinema” (Kuhn, “Heterotopia”). Of course, I have thus far been speaking in quite provocative or extreme terms; not every New Film historian eschews social and cultural contexts, and not every New Cinema historian completely ignores film text, whilst many scholars may not consider themselves to belong to one school of thought or the other. Yet, I argue that there is scope for a reconsideration or realignment between the two, which, from my perspective as someone who has previously been more concerned with the social contexts of cinemagoing history, involves considering the importance and role of the film text within audience perspective and experience.

Film Versus Environment

To exemplify the potential benefits an examination of text within social and cultural cinema historiography can provide, I shall reflect upon research I undertook as part of my PhD study, a project which explored the history of rural Welsh cinema exhibition and audience experience from the 1890s through to roughly 1970, and the impact made on my findings by an unexpected partial focus on film texts (Terrill). This PhD research aimed to provide, for the first time, social and cultural contexts of rural Welsh cinema history, a geographic region that has only received fleeting attention within existing works of Welsh cinema history, most notably that of David Berry and Peter Miskell, with the limited amount of scholarship concerning the country’s cinemagoing and exhibition histories having largely focussed on the southern cities and mining communities of the so-called Golden Age of British cinema (Hogenkamp; Ridgwell; Richards; R. James, “Very Profitable”; Moitra). The ethnographic component of this study had aimed to provide points of direct comparison to the Golden Age period of these more urban studies, first through a questionnaire and then a round of follow-up interviews, whilst also garnering responses concerning the 1950s and 60s. It quickly became apparent that accessing memories of the 1930s and 40s was going to be a difficult task, mostly due to my undertaking of this research being between 2015 and 2019 and, sadly, the generation of Kuhn and Jackie Stacey’s work now far fewer in number. As such, responses of those recalling the 1950s and 60s were dominant out of the 252 completed questionnaires, as per Table 1.

Year

1930s

1940s

1950s

1960s

% of respondents

1

9

48

87

Table 1: Decades recalled by respondents.

Ultimately, this dominance of post-Golden Age memories forced what proved to be a useful temporal focus, prompting findings and perspectives in relation to a variety of period specific contexts including: the steady economic decline of the British cinema industry (Stacey 83); global—or perhaps Western—social contexts such as the emergence of the teenager subculture and consumerism; and important Wales-specific factors such as a rise in Welsh nationalism and tensions of national identity. Equally, this period has in recent years received increased attention, in term of both British and global cinema history contexts, providing valuable points of comparison and contrast (M. Jones; Česálková; Treveri Gennari et al.).

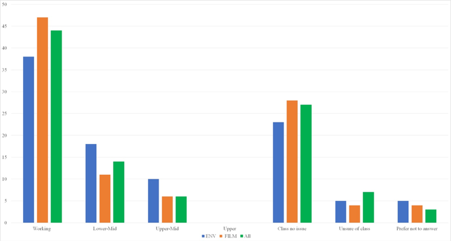

The research questionnaire was designed with a combination of closed and open questions, drawing on Stacey’s approach of limiting boredom whilst still eliciting qualitative and discursively rich answers, where needed (61–2). The questions aimed to garner a broad understanding of differing rural Welsh cinemagoing experiences prior to 1970, with examples including: if, and why, the respondent visited more than one venue; how frequently the cinema was attended at what they would consider to be their “peak” of attendance; if the reason for cinemagoing was for the film, social activity or a combination of the two, and if this changed at any point; and if there were any perceived advantages or disadvantages of attending a specifically rural venue in comparison to the urban. From my perspective, I anticipated that question nine would be the most illuminating or valuable open question in terms of cultural cinemagoing, with it asking respondents to recall their “most striking memories” of rural Welsh cinemagoing. Indeed, this question most typically returned the longest and most detailed answers, which were all coded in a results-driven manner, drawing upon the ethos of both Arlene Fink and Martin Barker, Jane Arthurs, and Ramaswami Harindranath. For example, discussions of films became FILM, mentions of popcorn or ice cream were coded as FOOD, whilst events that I deemed momentous, examples including a first kiss or German planes flying overhead, were coded as MOME, drawing on David Pillemer’s notion of momentous or “personal event” memories (50–1). Ultimately, fifty-four unique codes were created, with some being more specific variations of parental nodes.[1] Upon analysis and, as indicated by Table 2, memories that discussed the environment of the cinema-ENV—and those that discussed films-FILM—were the most frequently used codes. ENV included discourse of smells, quality of seating, décor, screen size or projector noise, whilst FILM covered the discussion of films, including detailed memories of specific titles, or more abstract discussions of a genre or character. Despite my aforementioned leaning towards a focus on cinemas as a shared social experience, I was not surprised that FILM was the second most employed code, as the cinema is a place where people go to watch films, after all. I was, however, surprised by the noticeable separation between those with ENV or FILM memories, with a crossover of only seven respondents in the dataset. I was unable to determine a clear causality for this separation, though some hints were made particularly in relation to class. There was a slight skew, when compared to the overall dataset, for FILM respondents having more frequently identified as working-class, whilst a similar difference is evident between ENV and the lower-middle and upper-middle class identifiers, as depicted in Figure 1. Notably, a similar observation is made by Robert James in his work on 1930s working-class tastes, noting it was the films, not venues, that primarily attracted working-class audiences (Popular Culture 17).

CODE

ENV

FILM

FORM

MOME

FOOD

Number of respondents

60

53

39

33

29

Table 2: Top five result-driven codes.

Figure 1: Class breakdown of ENV, FILM and overall dataset.

My means of dissemination largely relied on social media use, primarily local history Facebook groups, and it was my hope that this method would result in an even representation of the class demographics of rural Wales, due to the increased uptake of social media by those aged over sixty-five in Britain, along with rapidly accelerating adoption of internet use by those in Wales aged over seventy-five.[2] Whilst the lack of any upper-class identifying respondents may suggest that there was a skew, I instead argue that this actually reflects Wales’ nuanced relationship with class structures and Englishness, where a traditional upper-class is instead represented by the English or “English Welsh” (Perrins 38–9). My thesis covered the potential causes of such a separation between ENV and FILM in more detail, however, the most valuable outcome of identifying this trend was forcing me to explore the role of the film text within cinema memories. Here, I will present text-focussed findings from my questionnaires and interviews that ultimately benefitted the exploration of rural Wales’ social cinemagoing past.

Particularity of Place and Period

Earlier I noted that the gathered ethnographic data of this research ultimately had a focus on the 1950s and 60s, with memories of the 1930s and 40s proving much harder to locate. As mentioned, this was ultimately beneficial by providing a more specific temporal focus that featured a number of global and Wales specific cultural, social and economic factors that influenced rural Welsh cinemagoing memories. Primarily, my research to that point had been quite broad, using archival data to investigate an earlier period of between 1894–1930. There, I had been focussed on what John Caughie has identified as a “particularity of place”, a need to “capture the diversity of experience” by identifying localised factors that can differ within the same country or area (35). Whilst Caughie’s research concerned rural and urban Scotland, his arguments chimed with my desire to present rural Wales as a nonhomogeneous zone. Rather, and by modifying Denis Balsom’s socio-political and linguistically informed Three Wales Model, I considered and presented rural Wales as being culturally and socially diverse, which impacted experiences and matters of cinemagoing and exhibition. I have discussed such particularities in more detail elsewhere, with examples including the forgoing of Sunday screenings in more devout or middle-class areas of the country, whilst they proved to be a specific selling point of venues in more working-class areas, such as the southern mining town of Aberdare (Terrill, “More”). Yet, it became clear when exploring the FILM-coded responses that a particularity of period is equally important for considering contextual nuances of localised histories, especially when used in tandem with a particularity of place, and for identifying changing patterns of audience behaviour, tastes and memories between differing generations.

A notable example of a FILM-specific particularity of period, especially in comparison to research of Golden Age audiences, emerged from female respondents and their adolescent, and often sexually charged, recollections of male popstars. These observations were starkly different to Kuhn or Stacey’s findings of adolescent girls of the Golden Age, where their respondents typically discussed female stars and imitation of them. Yet it is important to first note that a great number of my male FILM respondents’ recollections do chime with the arguments of Golden Age research in relation to gender, primarily through preadolescent viewing of Westerns and memories of imitating and incorporating on-screen action into their play. For example, respondent 155 recalls “watching Westerns and pretending to shoot each other on the way home”, whilst 194 remembers “images of the USA. Walking out and being one of the actors. Westerns and the great outdoors.” Sarah Neely has noted a similar habit of recreation within the memories of rural Scottish audiences, arguing that the cinema created an “imaginative space” (784). For Neely, this “imaginative space” allowed the cinemagoer to “reimagine themselves and their world around them in different ways” and bridged the gap between them and the “disparate” cultures, identities, times and spaces presented through film (786). As Stacey has noted, the “pleasures of escapism” to be found in the British cinema auditorium are amplified by the “national” differences between Britain and the United States (118). For her respondents, the feeling of “losing oneself” was rendered more intense by the “unfamiliarity” of American culture (118). In terms of a particularity of place, those within this project’s dataset who overtly discussed the cinema as an opportunity to view a non-Welsh culture all identified themselves as having lived in the rural Mid- or North-West regions of Wales, with this idea of utilising film as a means of viewing other cultures being nicely evoked by respondent 171, who recalled being excited by the “whole experience of the world outside Porthmadog.”

Notably, discussions of the Western genre are disproportionally high within male FILM responses when compared to their female counterparts, with a similar trend being identified by Kuhn within her 1930s audience responses. She argues that male respondents have a tendency to reflect more on their childhood cinemagoing, and are particularly inspired by the Western, whereas women had “relatively little to say” about their preadolescent cinemagoing (100–1). Indeed, Stacey has positioned that filmic recreation of young women during this period revolved not around play and Westerns, but the female film star and her image, particularly in copying their favourite actresses’ hairstyle (168). Whilst no female FILM respondents discuss such imitation in my dataset, the mention of specific stars is more prominent than in comparison to their male counterparts, though not in a way that I had anticipated. Indeed, it is here that the notable modification of the findings of Kuhn and Stacey is located through the presence of the male popstar within these female FILM memories, with such examples being mentioned far more frequently than actresses. Female stars such as Katharine Hepburn, Joan Crawford and Doris Day, who are frequently discussed in either Kuhn or Stacey’s work, receive no mention here, whilst Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor are each mentioned once apiece across the questionnaire dataset with no elaboration beyond stating their names. Yet, the films and recorded concerts of popstars such as Elvis Presley, The Beatles and Cliff Richard are significant within the adolescent cinemagoing memories of female FILM respondents. For those who were younger during the late 1950s and 60s, this mania is experienced from a third-hand perspective, arguably as they had not reached the stage of adolescence that is discussed by Kuhn and Stacey as relating to such behaviour and attraction—sexually or otherwise—to film stars. For example, respondent 235 recollects “my dad taking me to see some of the Beatles films and not being able to hear anything because the older girls were screaming so much!”, whilst respondent 18 recalls being “very embarrassed by the gyrating hips”, in Cliff Richard and Elvis films, and that she “just couldn’t look”. Meanwhile, those who were teenagers at the time became actively involved in such behaviour, with respondent 98 remembering “queuing outside to see Elvis films, and going back to nick the poster from outside.”

This fascination with popstars within the memories of female respondents, who largely recall the late 1950s and 60s, is a logical cultural continuation of the interest in the glamorous actresses of the 1930s through to the early 1950s, the decades which Kuhn and Stacey’s respondents primarily recall. This argument has been explored by Stephanie Fremaux, who contends that the escapism and identification sought by the wartime and postwar female audiences of Stacey’s study culturally evolved into a fascination with popstars during the 1950s and 60s (17). Though mostly writing about USA audiences, Thomas Doherty argues that by the 1950s teenagers had become a distinct subculture, defined by their relative wealth and consumer power compared to previous generations, the heightened population of that age group due to the post–World-War-Two baby boom, and their awareness of themselves as teenagers (34). Indeed, the phenomenon of “Beatlemania” of the 1960s has been particularly linked to teenage girls and is argued by Ehrenreich, Hess and Jacobs to be “the first and most dramatic uprising of women’ssexual revolution” (85). The impact of sexual attraction or “fancying” of male stars is quite overtly demonstrated as overpowering the discursive content of memories in relation to female stars through the testimony of one interviewee. Here, the interviewee, respondent 235, occasionally makes mention of Elizabeth Taylor, but always within a frame of Taylor’s relationship with—and her own attraction to—Welsh actor Richard Burton. When specifically asked if she liked any female stars, she recalls: “Well, Elizabeth Taylor, obviously because she was with Richard Burton. [laughs] But, no not so much, not so much.”

How female fan activity was performed changed too, with the imitation of Kuhn and Stacey’s Golden Age audiences having shifted to an association with infatuation and screaming, as indicated by respondent 235. The experiences of rural Welsh female audiences can be observed to be a modification of findings from Golden Age scholarship, as identified through their responses to popstar films, and represent a globalised shift in culture. Whilst Kuhn’s audiences had to extract filmic sexuality from close reading—consciously or otherwise—of sequences such as the dance number within Top Hat (Mark Sandrich, 1935), these latter-1950s and 1960s were better supported culturally in presenting a different response to this new era of young male stars. It is also perhaps not surprising that male FILM respondents did not drastically modify the findings of young boys watching Westerns and incorporating that into their play. Whilst popstars and the teenage subculture swept the world in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the Western remained a popular genre of filmmaking into the early 1970s, particularly as part of a children’s weekend morning matinee in Britain (Heba and Murphy 309). Indeed, the ethnographic data of my research has conveyed matinees to be integral parts of social life for young rural Welsh children of the 1950s and 60s, particularly in smaller towns, where habitual attendance was as much a cornerstone of life as school or church. This, then, perhaps attests to the shared response of preadolescent memories of Westerns between my rural Welsh 1950s and 60s male FILM respondents and Kuhn’s of the Golden Age.

Wales and Welshness on Screen

In relation to other particularities of place and period identified through this study, the 1950s through to the early 1970s saw a notable rise in nationalism in Wales, with culture and the arts being key factors for Welsh people in expressing this (Leese 76). A link between politics, Welsh identity and cinemagoing has previously been considered in relation to early-twentieth-century urban Wales, with the majority of existing works concerning Welsh cinema history having explored the link between South Wales’ labour movement and cinema (Hogenkamp; Ridgwell; R. James, “Very Profitable”; Moitra). The period that my ethnographic research covers represented quite a different socio-political climate that that of the labour movement, with this rise of nationalism emerging from North and Mid Wales and with a focus on language and nationality, rather than class. Whilst such nationalism had been on the rise since the turn of the twentieth century, the 1960s saw a rapid increase in the movement, with Plaid Cymru, a political party dedicated to Wales and Welsh independence, winning its first parliamentary seat (Elias 59), as well as the emergence of more controversial groups such as Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru, perhaps better known as MAC, and the Free Wales Army. The preservation and celebration of the Welsh language was also boosted in this decade, with the establishment of the Welsh Language Society in 1962. The emergence of agencies dedicated to individual facets of Welsh identity, such as the Welsh Language Society, is argued by Alistair Cole to have allowed Plaid Cymru to shift its image as a somewhat conservative and “reactionary” movement that was focussed on the rural, to a party dedicated to the “distinctive social, economic, political and cultural development” of Wales as a whole (51).

Yet, there was limited FILM discourse within the questionnaires or even interviews that indicated a reflection of this, especially in terms of texts that resonated with Welsh identity or rising tensions. This is perhaps not surprising, as films made in or about Wales were scarce throughout the twentieth century, whilst Welsh language films were even more of a rarity, certainly for mainstream release. Furthermore, given my initial focus on cinemagoing as a social experience and a desire for a questionnaire that was not too leading in what it asked respondents to recall, my initial methods were not the best suited for elicitation of such discourse. The most evident discussions or allusions to nationalism came from the questionnaire dataset through discussions of national anthems being played after a feature film, which I had coded as an environmental factor of the cinemagoing experience.

Within FILM responses, there were a few nascent hints of text-focused memories reflecting matters of Welsh identity. Most typically, these examples presented a sense of the respondent considering themselves to have been part of a cultural in-joke, one shared with the rest of the specifically Welsh audience. Respondent 36 mentions “ironic cheers” when Welsh was used in Barbarella (Roger Vadim, 1968), with a similar shared audience experience noted by respondent 147, who recalls a throwaway joke in A Hard Day’s Night (Richard Lester, 1964), regarding a producer being demoted to Welsh radio, as having “brought the house down” and that “it was probably not that funny anywhere else but in Aber at that time seemed hilarious!” For these two respondents, references to Wales and or the Welsh language within non-Welsh productions constituted as a positive experience, one remembered fondly within their memories and as part of a shared collective audience experience. A more emotional experience is shared by respondent 185, who recalls that the only film she ever left during the opening was How Green Was my Valley (John Ford, 1941), due to the traditional Welsh song “Myfanwy” reducing her to tears. These respondents suggest a cultural pride about their Welshness, even when Wales is the butt of a joke, the country’s acknowledgement—even within an English or American production—elicited humour, as if it were designed as an in-joke for them, rather than about them. Such a relationship between a native tongue or heritage within a largely English-language distribution area is explored by José Carlos Lozano in relation to American-born respondents of Mexican descent who grew up in the Texas city of Laredo, which bordered their cultural homeland. For Lozano’s respondents, Spanish language and Mexican-produced films were more widely available than Welsh productions screening in Wales. However, some similarities are shared, I argue, between these bilingual audiences. Lozano considers his respondents as balancing their new cultural identity as American “without losing contact with their core Mexican cultural background” (40). English language films were dominant throughout Welsh cinemas, regardless of their geographic location or the degree to which the area was Welsh speaking. As such, these respondents have constituted such rare mentions or references to Welsh identity as part of their striking memories of rural Welsh cinemagoing.

As discussed, my initial questionnaire was designed to be limited in terms of how leading the questions were, particularly in relation to asking for striking memories of rural Welsh cinemagoing. This was ultimately beneficial in eliciting a wide range of narratives, discursive tropes and registers, and providing the ENV/FILM separation. However, with a fresh desire to explore filmic memories and their relationship with matters and issues of Welsh national identity, I sent a set of follow-up questions to those who had provided contact information in the initial questionnaire. These questions were more film and Welsh identity focussed, including asking respondents to list their favourite film stars, any films they recall being excited to see, and if they remember any films set in Wales, that featured Welsh actors or were fully or partly in the Welsh language. Ultimately, only twenty-one respondents replied to these follow-up questions, yet the answered provided some very useful data in terms of linking Welshness and film. No follow-up respondents recalled seeing a film in Welsh, whilst Richard Burton and How Green Was My Valley were by far the most commonly cited actor and film, with four and nine mentions, respectively. The fact that How Green Was My Valley is the most frequently mentioned “Welsh” film is indicative of the state of genuinely Welsh-produced and focused films prior to 1970, not least as it was filmed in California and featured mostly Irish actors. This did not deter respondent 109 who, in response to the question about recalling Welsh language films, states “no, but [I] loved Maureen O’Hara in How Green Was My Valley.”

How Green Was My Valley and Welsh Identity

The popularity of How Green Was My Valley and its inclusion as a “Welsh” film by respondents may seem somewhat counterintuitive, a film made in America with largely non-Welsh actors sporting some very questionably attempts at Welsh accents. Yet, the film clearly resonated with some, including bringing respondent 185 to tears, despite what I personally would have assessed to be failings or even stereotyping of Wales and its landscape. The number of responses from questionnaires and interviews regarding How Green Was My Valley are few in number yet pose an interesting question about the relationship between Welsh identity and filmic representation, and require further and more specific ethnographic investigation. In lieu of having the chance to carry out such research at the time of writing, I here offer a textual analysis combined with relevant scholarship as a means of exploring the nuanced relationship between How Green Was My Valley and constructs of Welsh identity. As David Berry notes, despite some shortcomings and absurdities such as the “ludicrously out-of-scale” miners’ cottages and their inflated interiors, the film can be argued to have a “deeper, more potent reality” found in its representation of an “imagined communal experience” (162). That is, the film presented an idealised version of a sense of community or small-town/village closeness that is part and parcel of what is itself an idealised facet of Welsh identity (Charles and Davis). Indeed, Welsh national identity and its symbology are relatively recent and quite actively constructed structures. Following years of English rule, a rise of industrialisation during the nineteenth century saw Wales reclaim its identity, becoming a “proto-nation”, as argued by David Andrews, that “manufactured” its identity through a resurgence of “pseudo” traditional Welsh dress, eisteddfods and retelling of mythology, along with the incorporation of new facets such as rugby and the national anthem, “Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau” (53). I argue that the relationship between How Green Was My Valley and this active reclaiming and creation of Welsh national identity, combined with the rise of nationalism during the period under study, suggests why the film proved popular with respondents, despite its shortcomings. Such an understanding is made more evident through a closer textual analysis of the film and its presentation of Wales. Indeed, much like the interiors of its fictitious mining cottages, the film in many ways is an inflated version of Wales and Welshness. Such an inflation is presented through the number of occasions we see members of the community marching through the streets, singing in unison and evoking the communal singing of Welsh chapel choirs. Notably, similar roaming gangs of singers are present in the equally idealistic Miramax-produced The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill but Came Down a Mountain (Christopher Monger, 1995), whilst the trope is lampooned in the dark comedy Twin Town (Kevin Allen, 1997), where a youth marching band engage in a curse-laden dispute with two corrupt police officers.

The mise en scène is equally embellished, with the dramatic Santa Monica mountains—products of the Californian filming location—peeking out in the backgrounds of many scenes, whilst the mine is located impossibly close to a row of impeccably clean cottages that better resemble a Cotswolds style than anything from South Wales. Elsewhere, there are examples of Welsh stereotypes, such as the prevalence of alcoholic beverages, including patrons of the village pub carrying their pints of beer to the scene of a tragic mining disaster, along with archetypes such as the highly maternal and empowered Welsh “Mam” (M. James 95–96) The women, most notably the sweetshop clerk, wear the traditional Welsh dress and hat, a garment very much built out of the active creation of Welsh identity and of dubious historical usage (R. Jones). Welshness also exists in opposition to Englishness within the film, with the strict schoolteacher, Mr Jonas, played by English actor Morton Lowry, embodying an upper class that is distinctive to England and its influence on Wales. Indeed, class is a complex issue in relation to Wales, with Daryl Perrins arguing that rather than a purely economic factor, those from “English Wales” constitute as the country’s upper class.[3] It is of note, then, that no questionnaire respondents from my research selected “upper class”, whilst the option of class being “not an issue in rural Wales” was the second most frequently selected identifier, at 27% across the dataset, and “working-class” being the most frequent at 44%. Jonas’s suit, Received Pronunciation accent and role of authority—also presented by the wealthy mine owner, Mr Evans—calls upon the sentiment of Wales being a colony under the English ruling class, with his caning of young Huw Morgan further highlighting this. This discipline is only delivered upon Huw after he has managed to physically confront and defeat his bully, an equally English sounding pupil in the school who had previously beaten Huw with no recourse from Jonas. It is not revealed in the film strictly what nationality Mr Jonas is, whilst the novel it was adapted from depicts him as being very much within the English Welsh archetype, somewhat ashamed of his Welsh heritage and with aspirations of being part of the English upper class. At one point, in the original source novel, Jonas even claims that “Welsh was never a language”, but rather a “crude” means of communication between “tribes of barbarians” (356). Satisfactory payoff is then produced from two of Huw’s family friends making an unannounced visit to the classroom, ultimately beating up Jonas under the guise of a boxing lesson. This sequence has a meta reverberance too, with actor Rhys Williams’s character Dai Bando administering this revenge, one of the few Welsh actors within the production. A representation of Englishness has bullied and beaten a defenceless Welsh child, before being beaten itself by an empowered and physically strong representation of Welshness, first through Huw learning to fight his classmate and later by Dai Bando.

With these textual elements in mind, it is perhaps less difficult to see why How Green Was My Valley proved to be popular with rural Welsh respondents, particularly against a backdrop of rising nationalist sentiment during the 1950s and 60s. Whereas other films from the era may have provided a more realistic version of Welsh life, such as David (Paul Dickson, 1951), or a similar box-office sheen whilst being partially filmed in Wales with some Welsh actors, The Proud Valley (Pen Tennyson, 1940), How Green Was My Valley conjured a semi-mythical version of an idealised Welsh identity that resonated with the actively reinforced constructs of Welshness. The titular refrain of “how green was my valley?”, a question that the adult Huw Morgan’s narration bookends the film with, suggests a mythical Wales, a time that was better for the people of Wales and their traditions or way of life. Of course, that it is arguably the most prominent film ever made about Wales likely did not hinder its prominence within respondents’ memories either. Directed by John Ford at the height of his fame and winning five Academy Awards, How Green Was My Valley had an international profile as a major Hollywood production. The film also received repeat screenings at Welsh venues over the years, with ledgers for Aberystwyth’s Coliseum cinema showing it having six separate successful runs at the venue between 1942 and 1968. Indeed, its screenings at the venue always performed well, even compared to contemporary releases, whilst its initial July 1942 week run was one of the most successful weeks in the venue’s history in terms of pure ticket sales, peaking at £131.22 on its second night, a Tuesday.[4]

Conclusion

Whilst this article has not offered any answers as to what potentially informed the stark separation between ENV and FILM memory narratives, it has provided examples of the benefit considering and analysing text can have when exploring cultural and social elements of cinemagoing past. As previously discussed, this is not exactly ground-breaking, with notions such as a “histoire totale”, as argued for by Barbara Klinger, having called on historians to collect and assess as many sources and forms of evidence as possible when exploring the past (108–10). Yet, there is a sense that two divergent camps of film and cinema history have emerged in recent years, prompting calls such as Biltereyst’s for a unification of our foci as historians.

Through searching for an answer to the ENV and FILM separation, a process which forced me to take a deeper look into text-centred memories, I have identified valuable modifications to existing scholarship, notably the impact of male popstars on female rural Welsh respondents in comparison to the works of Kuhn and Stacey. This, in turn, prompted the consideration of a particularity of period and not just place, with a focus on social and cultural cinemagoing having previously compelled a “spatial turn”, which Jeffrey Klenotic has argued to be a vital function of the New Cinema History (61). Meanwhile, textual analysis proved to be a useful tool for exploring the possibly counter-intuitive popularity of How Green Was My Valley, a Hollywood representation of Welsh life, that arguably complemented a cultural backdrop of rising nationalism through repeated screenings. Ultimately, a reinvigorated inclusion of text to this research benefited the desire to fuller understanding of rural Wales’ cultural and social cinemagoing history. Importantly, text here does not replace these cultural or social concerns, but rather complements their study and analysis in the same manner as any other form of competing archival evidence would. Simply put, striking a middle ground of the New Film and New Cinema provides potential for a more wide-ranging toolbox in our pursuit of uncovering and understanding history.

Notes

[1] Of the fifty-four descriptive codes, many could be considered off-shoots of parent nodes, an approach that allowed for more detailed analysis. For example, the code MAR for marriage—where someone recalled meeting or dating their future spouse at a cinema—always derives within talk than was also coded as DAT for dating.

[2] In 2018 Statista reported that 7.8 million of Britain’s 44.1 million Facebook users were over the age of fifty-five. A 2017 Welsh Government survey revealed that 40% of people over the age of 75 were actively using the internet in comparison to 22% in 2012–2013 (Gov.Wales). The dates of these studies represent the ethnographic data collection stage of my research.

[3] Geographically this includes the regions of Wales that most closely border England, as well as Pembrokeshire, due to its influx of English settlers. For the concept of an “English Wales”, Perrins draws upon Balsom’s Three Wales Model, which positions a similar British Wales grouping.

[4] The figure of £131.22 is converted from the pre-decimal form of £131/4s/4d.

References

1. Allen, Robert C., and Douglas Gomery. Film History: Theory and Practice. McGraw-Hill, 1985.

2. Andrews, David. “Masculine Hegemony of the Modern Nation: Welsh Rugby, Culture and Society, 1890–1914.” Making Men: Rugby and Masculine Identity, edited by John Nauright and Timothy J. L. Chandler, Routledge, 1996, pp. 50–69.

3. Balsom, Denis. “The Three Wales Model.” The National Question Again: Welsh Political Identity in the 1980s, edited by John Osmond, Gomer Press, 1985, pp. 1–18.

4. Barbarella. Directed by Roger Vadim, Paramount Pictures, 1968.

5. Barker, Martin, et al. The Crash Controversy. Wallflower Press, 2001.

6. Berry, David. Wales and Cinema: The First Hundred Years. University of Wales Press, 1994.

7. Biltereyst, Daniel. “Audience as Palimpsest: Mapping Historical Film Audience Research.” Researching Past Cinema Audiences: Archives, Memories and Methods conference, 26–28 March 2018, Aberystwyth University.

8. Bosma, Peter. Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives. Columbia UP, 2015.

9. Caughie, John. “Small-Town Cinema in Scotland: The Particularity of Place.” Cinema Beyond the City: Small-Town and Rural Film Culture in Europe, edited by Judith Thissen and Clemens Zimmermann, Palgrave, 2016, pp. 23–37.

10. Česálková, Lucie. “Silence under the Linden Tree: Rural Cinema-Going in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s and 1960s.” Rural Cinema Exhibition and Audiences in a Global Context, edited by Daniela Treveri Gennari, Danielle Hipkins, and Catherine O’Rawe, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 261–79.

11. Chapman, James, Mark Glancy, and Sue Harper, editors. The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

12. Charles, Nickie, and Charlotte Aull Davies. “Studying the Particular, Illuminating the General: Community Studies and Community in Wales.” The Sociological Review, vol. 53, no. 4, 2005, pp. 672–90, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00590.x.

13. Cole, Alistair. Beyond Devolution and Decentralisation: Building Regional Capacity in Wales and Brittany. Manchester UP, 2006.

14. Coliseum Cinema Account Book, 1993.22.4, 1942. Ceredigion Museum, Aberystwyth.

15. David. Directed by Paul Dickson, Regent Films, 1951.

16. Doherty, Thomas. Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s. Temple UP, 2002.

17. Drake, Philip. “Reputational Capital, Creative Conflict and Hollywood Independence.” American Independent Cinema: Indie, Indiewood and Beyond, edited by Geoff King, Claire Molloy, and Yannis Tzioumakis, Routledge, 2013, pp. 140–53.18. Ehrenreich, Barbara, et al. “Beatlemania: Girls Just Want to Have Fun.” The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media, edited by Lisa A. Lewis, Routledge, 2003, pp. 84–106.

19. Elias, Anwen. “From Protest to Power: Mapping the Ideological Evolution of Plaid Cymru and the Bloque Nacionalista Galego.” New Challenges for Stateless Nationalist and Regionalist Parties, edited by Eve Hepburn, Routledge, 2011, pp. 55–79.

20. The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill but Came Down a Mountain. Directed by Christopher Monger, Miramax Films, 1995.

21. Fink, Arlene. The Survey Handbook. Sage, 1995.

22. Fremaux, Stephanie. The Beatles on Screen: From Pop Stars to Musicians. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

23. Gov.Wales. National Survey for Wales, 2016–17 Internet Access and Online Public Services. gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-02/national-survey-wales-internet-access-and-online-public-services-2016-17.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2018.

24. A Hard Day’s Night. Directed by Richard Lester, United Artists, 1964.

25. Harper, Sue. “‘It Is Time We Went Out to Meet Them’: Empathy and Historical Distance”. Participations, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 687–97.

26. Heba, Gary, and Robin Murphy. “Go West, Young Woman! Hegel’s Dialetic and Women’s Identities in Western Films.” The Philosophy of the Western, edited by Jennifer L. McMahon and B. Steve. Csaki, UP of Kentucky, 2010, pp. 309–28.

27. “Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau.” Words by Evan James, tune by James James, 1856.

28. Hogenkamp, Bert. “Miners’ Cinemas in South Wales in the 1920’s & 1930’s”. Llafur, vol. 4, no. 2, 1985, pp. 64–76.

29. How Green Was My Valley. Directed by John Ford, Twentieth Century Fox, 1941.

30. James, Manon Ceridwen. Women, Identity and Religion in Wales: Theology, Poetry, Story. U of Wales P, 2018.

31. , Robert. Popular Culture and Working-Class Taste in Britain, 1930–39. Manchester UP, 2010.

32. ---. “‘A Very Profitable Enterprise’: South Wales Miners’ Institute Cinemas in the 1930s.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol. 27, no. 1, 2007, pp. 27–61, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01439680601177114.

33. Jones, Matthew. “Far From Swinging London: Memories of Non-Urban Cinemagoing in 1960s Britain.” Cinema Beyond the City: Small-Town and Rural Film Culture in Europe, edited by Judith Thissen and Clemens Zimmermann, Palgrave, 2016, pp. 117–29.

34. Jones, Rhian E. Petticoat Heroes: Gender, Culture and Popular Protest in the Rebecca Riots. U of Wales P, 2015.

35. Klenotic, Jeffrey. “Using GIS to Explore the Spatiality of Cinema.” Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies, edited by Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 58–41.

36. Klinger, Barbara. “Film History Terminable and Interminable.” Screen, vol. 38, no. 2, 1997, pp. 107–28, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/38.2.107.

37. Kuhn, Annette. An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory. I. B. Tauris, 2002.

38. ---. “Heterotopia, Heterochronia: Place and Time in Cinema Memory.” Screen, vol. 45, no. 2, 2004, pp. 106–14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/45.2.106.

39. Leese, Peter. Britain Since 1945: Aspects of Identity. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

40. Llewellyn, Richard. How Green Was My Valley. 1939. Simon and Schuster, 2009.

41. Lozano, José Carlos. “Film at the Border: Memories of Cinemagoing in Laredo, Texas.” Memory Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, 2017, pp. 35–48, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016670787.

42. Maltby, Richard. “New Cinema Histories.” Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies, edited by Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 3–41.

43. Miskell, Peter. A Social History of the Cinema in Wales 1918–1951: Pulpits, Coal Pits and Fleapits. U of Wales P, 2006.

44. Moitra, Stefan. “‘The Management Committee Intend to Act as Ushers’: Cinema Operation and the South Wales Miners’ Institutes in the 1950s and 1960s.” Cinema, Audiences and Modernity: New Perspectives on European Cinema History, edited by Daniel Biltereyst, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers, Routledge, 2012, pp. 99–115.

45. Neely, Sarah. “‘Reel to Rattling Reel’: Telling Stories about Rural Cinema-Going in Scotland.” Participations, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 778–95.

46. “Myfanwy.” Composed by Joseph Parry, 1875.

47. Perrins, Daryl. “Arcadia in Absentia: Cinema, The Depression and the Problem of Industrial Wales.” Regional Aesthetics: Mapping UK Media Cultures, edited by Ieuan Franklin, Ieuan Franklin, and Kristin Skoog, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 35–55.

48. Pillemer, David B. Momentous Events, Vivid Memories. Harvard UP, 1998.

49. The Proud Valley. Directed by Pen Tennyson, Ealing Studios, 1940.

50. Richards, Helen. “Memory Reclamation of Cinema Going in Bridgend, South Wales, 1930 – 1960.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol. 23, no. 4, 2003, pp. 341-55, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0143968032000126636.51. Ridgwell, Stephen. “South Wales and the Cinema in the 1930s.” Welsh History Review, vol, 17, no. 4, 1995, pp. 590–615.

52. Stacey, Jackie. Stargazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship. Routledge, 1994.

53. Statista. UK: Number of Facebook Users by Age and Gender 2018. www.statista.com/statistics/507417/number-of-facebook-users-in-the-united-kingdom-uk-by-age-and-gender. Accessed 12 July 2018.

54. Terrill, Jamie. An Investigation of Rural Welsh Cinemas: Their Histories, Memories and Communities. 2019. Aberystwyth University, PhD thesis.

55. ---. “More to the UK than England: Exploring Rural Wales’ Cinemagoing History Through its Showmen.” Participations, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 738–61.

56. Top Hat. Directed by Mark Sandrich, RKO Radio Pictures, 1935.

57. Treveri Gennari, Daniela, and Sarah Culhane. “Crowdsourcing Memories and Artefacts to Reconstruct Italian Cinema History: Micro-Histories of Small-Town Exhibition in the 1950s.” Participations, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 796–823.

58. Treveri Gennari, Daniela, et al. Italian Cinema Audiences: Histories and Memories of Cinema-Going in Post-war Italy. Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

59. Twin Town. Directed by Kevin Allen, PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, 1997.

Suggested Citation

Terrill, Jamie. “Filmgoing or Cinemagoing? The Role of the Film Text within Cinema Memory.” History of Cinemagoing: Archives and Projects Dossier, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 21, 2021, pp. 178–192, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.11

Jamie Terrill is a Research Associate at Lancaster University, currently working on the AHRC-funded research project “Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive”. His recently completed PhD explored a social history of rural Welsh cinemagoing, a topic on which he has also published. He is a coeditor of the upcoming edited collection Researching Past Screen Audiences.