Capturing European Crime: European Crime Cinema at European Film Festivals

Russ Hunter

Abstract

As “shop windows” for newly produced but not-yet-released films, the study of festivals is one measure by which it is possible to assess the nature, presence and relative quantity of European crime films made in any given year. This article explores the presence of European crime films at European film festivals by examining the complete festival programmes from Cannes, Berlin and Venice. These three festivals are widely regarded as the most prestigious and largest in Europe (forming part of the global “Big 5” alongside Sundance and Toronto) and as such are premier destination for films of all types, particularly European productions. The prestige and visibility afforded by them means that they are key sites of exhibition, marketing and potential distribution to any film that is programmed there. The aim is to begin substantiating the numerical, national and transnational make-up of European crime cinema by using its presence on the European festival circuit as means to highlight its contemporary production status. A systematic analysis of all films programmed at Cannes, Venice and Berlin in order to identify the European crime films present identified a total 289 films (8.05% of the total films programmed at these festivals) out of 3587 films surveyed across a five-year period (2016–2020).

Article

Typically, studies of crime cinema have wrestled with the complexity of its generic boundaries and taken a case study approach in textually breaking down the intricacies and dynamics of individual texts (Leitch; Chibnall and Murphy). Once considered as critically unnoteworthy, historically part of the drive with such work has been to legitimise the study of these films and establish their interconnected relationships to other generic forms and, in so doing, create a canon of crime films. The appeal of crime for audiences is broad and, as Kirsten Moana Thompson notes,

From the tabloid press to pulp fiction, and from the stalwart television franchises Law and Order and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation to movies about serial killers, gangsters and private eyes, film, television and popular culture reflect our continuing fascination with crime. (1)

But whilst Anglo-American scholarship has naturally focused upon exploring the generic make-up of its own domestic crime cinema, collectively its European counterpart (of which British crime films are also decidedly a part) still remains what, in a very different context, Julian Petley once referred to as a “lost continent” of films. Given the large geographical span of Europe as a continent and both its interdependency and intertwining as a political entity (both formally in relation to the European Union and beyond), understanding the “lay of the land” in terms of film production, exhibition and consumption is a complex and problematic task. This is even more complex when attempting to understand the dynamics of individual genre production and none more so than the European crime film. Continental European crime cinema exhibits a key tension that American—and to a lesser extent British—crime films do not: they tend to be inherently national in their appeal, struggling to cross national borders as popular cinema.[1] At the same time, their very different cultural, linguistic and historical contexts often make them hard to conceptualise collectively. This in part explains the lack of macro-level studies of European crime cinema and the related absence of a clear sense of what is being produced, where and when. One potential beginning here is to view film festivals, as pan-European exhibition sites, as a means of establishing the dynamics of European crime film production.

Whilst it is not the purpose of this article to rehearse the value or function of film festivals, it is worth noting a few key factors. The function of festivals has often tended to be viewed as a key exhibition space and, as Jeffrey Ruoff notes, a place to “nurture independent films, showcase national cinemas, and bring international films to ever-increasing audiences” (1). To put it more simply, as veteran festival director Marco Mueller has argued, it reveals what the market normally hides (qtd. in Iordanova 109). Despite often being viewed as lowbrow genre domestically, European crime films often struggle to have any significant popular presence outside of their own local markets, and “[a]s soon as they manage to cross their national borders their cultural capital changes, entering the realms of specialist cinemas, with their festivals, art-cinema theatres, and late-hour TV broadcasting” (Baschiera 592). This makes the role of festivals even more important in relation to a genre where the cultural specificities of crime cinema become less accessible in other European markets. Within a European film market context, therefore, festivals are a space that allow crime films to have the opportunity to circulate in ways that might otherwise prove problematic. Festivals here can, to an extent, be viewed as free-floating exhibition spaces that allow the spotlight to be shone on films that might in other circumstances be restricted to strictly local (and sometimes regional) markets. Whilst they are generally explicitly tied to a specific city in a specific nation, they offer the opportunity for crime films to sit side-by-side with each other, regardless of country of origin, in a viewing context that is specifically and competitively designed to facilitate such a comparison. To this end, as Stefano Baschiera has observed, “the main chance for European crime films to cross national borders is through the festival circuit […] the festival run adds prestige and cultural capital to the production, further establishing it as ‘quality cinema’” (594). There is, then, a paradox at the heart of European crime cinema as a genre: it is often seen as popular (or even lowbrow) entertainment in its own domestic market, but once it passes national borders its very cultural specificity renders it liable to be exhibited and viewed via an art cinema framework.

But festivals do not merely act to reveal what may otherwise remain hidden (or obscure). Whilst Mueller’s much quoted maxim might be apposite in many cases, festivals do not just reveal what markets hide. Festivals are part of the film market—indeed some larger festivals such as Cannes literally have markets attached to them—and as such facilitate the functioning of the European and international aspects of that market. What a study of festivals can do is offer a window into the general production levels of specific genres and the relative production picture within individual national or regional contexts. As “shop windows” for newly produced but not-yet-released films, the study of festivals is one measure by which it is possible to assess the nature, presence and relative quantity of European crime films made in any given year. It is not, of course, an absolute measure given that not all films that are produced are programmed at film festivals, and those that are will be scattered across a number of generalist events. Yet, at any given festival the presence of so many crime films in one placedoes allow us to begin to build a picture of European crime cinema both in relation to national production and relative national production levels that is otherwise complex and hard to access. As Kirsten Stevens has argued, the “study of film festivals is inherently transnational, transmedia and interdisciplinary in its approach”, a fact that makes festivals the ideal loci to explore both the presence and interconnectedness of European forms of crime cinema (46).

If we accept that festivals offer an opportunity to garner a snapshot of crime film production in Europe, the difficulty comes in how to systemically capture and analyse their presence. Gathering such data is not as straightforward as it seems. Whilst, as Stevens has observed, an “ever-widening array of methodologies, disciplinary concerns and theoretical frameworks” are now employed within the field of film festival studies, the systematic analysis of film genres lacks an established methodological approach in relation to film festivals (47). As such, this essay explores the presence of European crime films at European film festivals by examining the complete festival programmes from the three major European film festivals: Cannes, Berlin and Venice. These three festivals are widely regarded as the most prestigious and largest in Europe (forming part of the global “Big 5” alongside Sundance and Toronto) and, as such, are premier destination for films of all types, particularly European productions. The prestige and visibility they afford means that they are key sites of exhibition, marketing and potential distribution to any film that is programmed there. The aim is to begin to substantiate the numerical, national and transnational make-up of European crime cinema by using its presence on the European festival circuit as means to highlight its contemporary production status. A systematic analysis of all films programmed at Cannes, Venice and Berlin in order to identify the European crime films present identified a total 289 films (8.05 % of the total films programmed at these festivals)[2] out of 3587 films surveyed across a five-year period (2016–2020).[3]

Given the apparent flexibility of what precisely the term “crime film” refers to, identifying crime films at film festivals is loaded with difficulties. In the first instance, the problem with attempting to identify European crime films across festival programmes is both how to do this this as objectively as possible and how to do it consistently. Thompson stresses that the scope of crime narratives is often broad and that their particular focus can vary from culture to culture (1). This makes objective classifications more complex but also more necessary. Defining a European crime film is further complicated by considering exactly what aspect of the film might make it European. Do, for instance, the films need to be set in a European country? Should all the production partners be European? Can a European nation be a minor production partner alongside a non-European nation, and it still be considered a European crime film? In order to provide as broad a sense of the European crime film presence at Cannes, Venice and Berlin, European crime films are defined here as those films that have at least one European production partner, with Europe being considered as a geographical (rather than political) entity. This provides as inclusive a picture as possible of the production and festival exhibition of European crime cinema across the continent. There are several important additional considerations here. Firstly, festivals rarely (if ever) offer generic classifications (and, in any case, these may differ from festival to festival) for the films they programme, either in their official (physical) programmes or online. Festivals are programmed, for the most part, via programming strands and this is reflected in the way the programme is both positioned and marketed by individual festivals. Equally, given the number of films under analysis here, it was impossible to make generic judgements based on viewing all of the films in this sample (and in any case this would require some guiding framework). As such, in order to maintain a consistent reference point, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) genre classification listed for each film was used. [4] Importantly, these IMDb genre assignations for individual films are created (in most cases) by film production companies when officially registering any given film, meaning that it is possible to reflect on how they self-identify their work. In addition to this, the plot summary of each film was cross-referenced with the genre classification and films that were very obviously crime films, but not labelled as such on the IMDb, were coded as crime films. This triangulating process helps to avoid imposing definitions from above and makes the generic identification a much more “bottom up” process. However, it also allowed for adjustments where—for whatever reason—a film’s producers had decided not to identify it as a crime film. As I will suggest below, the IMDb classification can often be used strategically and be viewed, àlaRick Altman, as a part of the producer’s game.

Exactly what to count as part of a festival’s film programme is less clear than it at first might seem. Whilst it is usually straightforward to identify films in competition at Cannes, Berlin or Venice, for instance, the picture is much less clear in considering other parts of the programme. Major festivals often have multiple programming strands (that can vary from year to year) and understanding what has been programmed as part of any given festival in any given year is far from simple. Archival information on previous programmes is often fragmented in terms of its access points and, in any case, information on specific films can vary in terms of detail. So, for instance, individual festival websites and/or IMDb film data is often partial or missing for films in the various short film programmes and frequently entirely absent for specific strands, particularly those that have a relatively low profile. The Cinéfondationprogramme at Cannes, which focuses on films made by students at film schools, for instance, is made up of films for which it is hard to locate even basic information pertaining to narrative or genre. This complicates attempts to identify crime films as there is simply not enough information to do so consistently. Equally, it can be difficult to separate broader festival events from the central programme. At Cannes, for instance, the Marché du Film and the festival are “two side of a single coin” and operate side by side (“Marché”). But the films available at the Marché are not part of the festival per se (they are not officially screened by it) but they do form a key part of the broader Cannes offering and identity. The Marché, however, screened 857 films in 2019. Given the make-up of the official Cannes programme itself in 2019 (it screened eighteen crime or crime-based films that year), it is safe to assume that the Marché would have a significant number of crime films present. All of which makes the process of elucidating the presence of crime films at these festivals both complicated and necessarily fragmentary.

One of the criticisms levelled at festival studies—particularly by those working within it—is that there has been a disproportionate focus on large A-list festivals, given that these represent a tiny proportion of the between 3,000–6,000 film festivals that exist (de Valck). The move away from a focus on larger (particularly A-list) festivals has therefore been a welcome step in helping to remove the reductive temptation to see festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Sundance and Toronto as gateways into understanding key debates surround the film festival circuit as a whole. That noted, this does not mean that there are not ways in which a focus on them can still be instructive. In attempting to understand the presence of crime films on the European film festival circuit, an examination of Europe’s most high profile and largest festivals offers the opportunity for a clear and immediate sense of the current production status of European crime cinema. There are other reasons for focusing on “the big 3” that do not relate to the relative popularity, importance and size of Cannes, Venice and Berlin, but to a (perhaps) surprising lack of crime-specific film festivals. We might expect, for instance, a popular genre form such as crime cinema to have numerous specialist film festivals dedicated to it, in the same way that other forms of popular genre cinema such as horror, sci-fi, action and fantasy do (to name but a few). But, whilst in Europe the post-millennium period saw a rapid and notable growth of a variety genre-focused festivals—demonstrating the vibrancy and diversity of what Marijke de Valck has identified as specialised but non-political festivals—dedicated crime film festivals have shown little to no development. There are several reasons for this. In part, this lack of growth is symptomatic of the fact that crime film festivals have little or no presence on the European film festival circuit at all. In fact, Europe has a negligible number of festivals specifically dedicated to crime films and beyond this there are an extremely limited number of crime-specific film festivals worldwide. It is telling, for instance, that the industry-standard film submission portal FilmFreeway.com does not list “crime” as one of its searchable “Festival Focus” categories. These exist to allow filmmakers to quickly filter festivals by type and focus on a mix of genres and identity-based categories that include (amongst others) action/adventure, black/African, comedy, horror, LGBTQ and women. Crime is notable by its absence.

It is instructive to compare this situation to other forms of genre-based cinema, where there are clearer signs of specialised and genre-specific festivals. In Europe alone, for instance, there are over 120 horror-dedicated or related festivals (Hunter), but as of 2021 less than ten crime-related ones. Indeed, the International Film Festival of Detective Films & Television (Moscow, at his twenty-third edition in 2021) stands out precisely because it is so unusual. Other examples are either slightly quirky (the International Police Award Arts Festival in Florence), are hybrid events (Anatomy: Crime-Horror International Film Festival in Athens) or one-offs such as The Manchester Crime and Justice Festival (2019) that was tied to Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service Insights ’19 Initiative.5] There are also an extremely limited number of short crime or crime-based festivals such as Corto Nero Noir Short Film Competition (Naples) or the Film Noir Festival in Albert (France). Whilst this list is not exhaustive it does point to a genre that—for whatever reason—has not seen an associated rise in dedicated film festivals in a post-millennial period that saw an explosion of genre-related events. What is also notable is that none of these festivals are straightforwardly crime film festivals, but instead are mixed genre events (Anatomy: Crime-Horror International Film Festival) or focus on one particular sub-section of the crime genre (International Film Festival of Detective Films & Television, Corto Nero Noir Short Film Competition, Film Noir Festival).[6] This is, perhaps, suggestive of some of the complications inherent in uses of the label of “crime cinema” and its industrial application. More substantially, a lack of crime festival growth is indicative of a wider industrial issue with the particular status of crime as a generic identifier. Crime has tended to be an umbrella term that “encompasses many genres, sub-genres and film cycles” ranging from police to procedurals to film noir (Thompson 2). These amorphous and often complex generic boundaries therefore make it a “forbiddingly broad genre” and one that is generically hard to pin-down (Leitch 2). Given this, crime is a genre that, due to its inherently composite generic nature, appears in a variety of more generalist festival spaces, few of which dedicated solely to crime. As such, they tend to appear at festivals such as Venice, Cannes and Berlin, as well as other major European (and international) events.

It was noted above that the definition used for “crime film” was taken from the IMDb. Whilst this was in part to allow for a consistency of identifying what constituted a “crime film”, it is also instructive because the IMDb genre definitions are, for new releases, user led. What this means, in reality, is that the genre assignations on the site are created by any given film’s producers and, as such, it is possible to see the ways in which those who produce European crime films are generically positioning their own work. Not one of the 289 crime films identified here is labelled as purely a “crime” film. Crime, it seems, might be popular at the box office, but it is a genre label that producers are reluctant to use on its own. Instead, films labelled as crime films are always generically hyphenated as, for instance, a crime-drama, a crime-drama-thriller and so on. What this means in practice is that crime is not used as a distinct identifying marker for European crime films but is always linked to another generic tag. Most commonly, crime is linked to drama, and for the most part some combination of crime-drama (often with additional generic modifiers) is applied. In fact, the top ten most used genre labels are dominated by a combination of the term “crime” and “drama”. There are several possible conclusions that can be drawn from this. This suggests that crime itself is not seen as a fruitful or productive generic term when used on its own—it always needs another genre marker to orientate it. Moreover, as Baschiera has argued, “crime is, along with drama, the genre where realism features more prominently and offers an opportunity to reflect on social issues, ethical dilemmas, and the depth of the human condition” (590). In short, films that are “stories about illicit worlds and transgressive individuals” are necessarily going to contain drama (Thomspon 2). As such, this tendency to reflect or explore realist filmmaking means that drama is a natural corollary of making crime films and hence the label qualifies any singular use of the term “crime”. But, given that crime cinema has traditionally had a low critical and artistic reputation (normally being viewed as a form of genre cinema), the addition of drama as a genre qualifier might also be explained as a culturally legitimising strategy. Whilst these factors help to explain the predominance of the “drama” in addition to crime as a descriptor for European crime films, they do not wholly clarify it. Arguably, part of this cultural legitimisation strategy in mobilising the genre designation of “drama” is to utilise its cachet to both distributors and to festivals programmers (and counteract any negative connotations that the term “crime” alone might bring). Due to its broad (and somewhat vague) nature, using the genre tag of “drama” (which often appears as almost a default description) allows producers to position their films in a much more generalist way and avoid potentially being side-lined as a genre film. There was a very clear tendency for the films analysed here to follow this strategy. In fact, out of the 289 crime films identified across the film programmes for Cannes, Venice and Berlin here, 212 use “drama” as either a hyphenated or sole genre descriptor.

Figure 1. Screened at Cannes in 2019: Oleg, by Juris Kursietis.

Tasse Film, Iota Production, iN SCRiPT, Arizona Films Productions, 2019. Screenshot.

This reluctance to use only the genre marker of “crime film” is not just evident in relation to variations on the use of the term “drama” as a qualifying genre. Whilst this is clearly the most prevalent way in which crime films are positioned, it is notable that the total of 289 crime films contained 31 documentaries but only five (16%) of these used the term “crime”. For the most part these films are simply identified as “documentaries”. In part, this relates to documentaries often circumventing traditional generic identification, instead typically being singled out by their mode of filmmaking, and not genre. However, in some instances this appears curious and throws light onto the recalcitrance of producers to use the label of “crime”. An example will serve to illustrate this point. Asif Kapadia’s Diego Maradona (2019), which screened out of competition at the 2019 edition of the Cannes film festival, is a documentary that traces the Argentine footballer’s move from Barcelona to Naples in 1984. To that end, it is possible to view it rather straightforwardly as a sports documentary. As such, it is listed on the IMDb as “documentary, sport” (which leads us to assume that this is how its producers wished to position it). However, in reality a large portion of the film deals with Maradona’s intimate connection to the Camorra (as well as suggesting that the club itself might also have connections). Whilst the film is very clearly a sports documentary, it could also be identified as a “crime documentary” (or that very niche category of “crime sports documentary”). Regardless, this points to the challenges in being able to effectively outline the generic scope of European cinema.

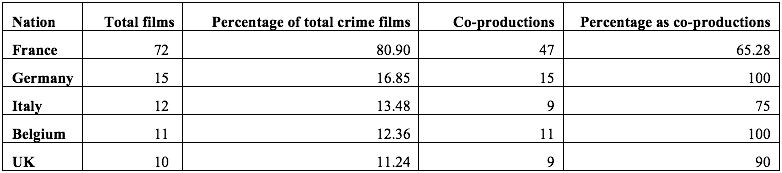

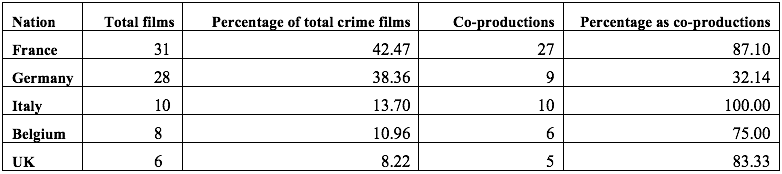

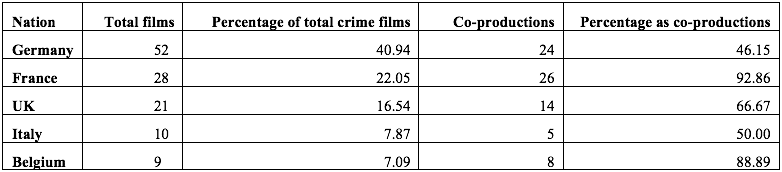

The following tables highlight the number of films by individual production country where the national production partner is involved either as the sole producer or as a co-producer of a European crime film (Tables 1–3). The tables also list the number of co-productions each has been involved with, the percentage this forms of the total for that country. In each case, the top five production partner countries are listed.

Table 1 – Crime films at the Cannes Film Festival by national production partner (2015–2020)[7]

The total number of films identified as crime films were 89 out a total of 901 screened.

Table 2 – Crime films at the Venice Film Festival by national production partner (2015–2020)

The total number of films identified as crime films were 73 out a total of 717 screened.

Table 3 – Crime films at the Berlin Film Festival by national production partner (2015–2020)

The total number of films identified as crime films were 127 out a total of 1969 screened.

As Tables 1–3 demonstrate, French crime films (or films where there was at least one French co-production partner) were clearly the dominant national crime film from 2015–2020 representing 131 out of the total of 289 (45%) crime films. There is a notable national dimension to what is programmed at each of the festivals. At Cannes, for instance, 80.90% of the total number of crime films shown were French. Whilst French crime films were also a dominant part of the crime-based film programming at Venice (31 films, making 42.47% of the total crime films programmed) and Berlin (28 films, making 22.05% of the total crime films programmed). In these cases, the figures represent films that are either entirely French or that have at least one French co-production partner and as such it is difficult from raw data alone to ascertain if, for instance, there is something about French culture, society or its industry that particularly encourages crime film production or if this merely reflects broader levels of French film production and co-production arrangements. Moreover, it is also the case that Italian crime films are strongly represented at Venice (10 films)—second only behind France in terms of numbers of crime films present—and German crime films are the most numerous (52 films) at Berlin.It is, perhaps, unsurprising that—albeit in a varied order—the top five crime-film-producing nations are the same across each of the festivals investigated. Whilst it is possible to see a clear “country of origin” bias for each of the three festivals (or, at least, it is possible to say that each screens a significant amount of crime films from its own nation), it is notable that the top crime-film producers are all Western European nations. The question here is whether or not this is because of a favouring (for whatever reason) of Western European crime films or if, in absolute terms, this happens to be where the majority of European crime film is produced. The latter would seem more likely given that France, Italy and Germany are traditionally amongst the larger European film-producing nations. This low level of presence might, in part, be explained by the geographical positioning of Venice, Cannes and Berlin in Western Europe and the noted tendency towards their own national crime cinema; either because of a desire to promote national cinema or because it appears more culturally relevant than non-Italian, French or German crime cinema. Further research is required to understand the dynamics at play here and to substantiate exactly why French crime film (in particular) is the dominant national crime cinema at the three major European film festivals.

European crime cinema, then, plays an important part in the programming of Europe’s major film festivals, as evidenced by Venice, Cannes and Berlin. There is a clear dominance by crime films from Western Europe and, most notably, by France, Italy and Germany. France, in particular, makes (either as sole or co-producer) significantly more crime films than any other European country, producing nearly twice as many films (131) as the next most productive country, Germany (73). More generally, the data also shows that a significant proportion of European crime films are co-productions (often with multiple partners), with a small minority being set outside of the geographical boundaries of Europe. But the picture is not as straightforward as an (albeit complex) counting process. It has been noted that the generic label “crime” is never used on its own, and that makers of European crime films do not—or, importantly, do not want to—see their films as solely crime films, but instead use a variety of additional genre labels to make sense of them to viewers and position them more effectively in the international film market. Crime films offer a kind of “push-pull” for their creators. It has long been a derided critical category and as Steve Chibnall and Robert Murphy point out in their influential British Crime Cinema, the genre was long critically unfavoured and seen as an illegitimate area of study within the academy precisely because crime films were, for the most part, seen as low-brow genre fare. At the same time, they are often broadly popular with audiences, although—with the exception of American crime cinema, which plays broadly across film festivals in Europe and is more widely distributed in general—box office success tends to be domestic. As Baschiera has noted, when these films travel, their socio-cultural register changes and the European crime film is more likely to be exhibited and understood within an art cinema context, not a popular cinematic one.

In conclusion, in discussing the presence of European crime films at three major European (and global) film festivals such as Cannes, Venice and Berlin, in spite of the difficulties in identifying them in the programmes, this article has sought to begin a process of building a picture of the production and (festival) exhibition presence of the genre. In so doing, the aim has been to begin to provide a clearer picture of what level European crime film production is at, where it is being made and with whom. But such processes are, by their very nature, beginnings. There is much work to do now in more clearly understanding the dynamics of European crime cinema as a transnational entity and in understanding more clearly the dynamics of the statusthat these films have, not only at nationally “free-floating” events like festivals, but within the broader context of European cinema.

Notes

[1] There is a curious point of departure here with European crime television where Scandanavian crime dramas in particular have proved popular in international markets.

[2] A number of films in the sample, for instance, were identified as crime films from their plot descriptions (where they were very obviously crime films) but labelled by their producers as dramas on the IMDb.

[3] The period under analysis here includes the impact of COVID-19 and the global pandemic, which saw a significant effect upon the 2020 edition of Cannes, in particular. Whilst Venice and Berlin 2020 went ahead as live events under strict Covid protocols, the live edition of Cannes was cancelled and replaced by a later very limited set of screenings.

[4] The IMDb offers a guide of potential genres and definitions, of which “crime” is one. This is listed as “Whether the protagonists or antagonists are criminals this should contain numerous consecutive and inter-related scenes of characters participating, aiding, abetting, and/or planning criminal behaviour or experiences usually for an illicit goal. Not to be confused with Film-Noir, and only sometimes should be supplied with it” (“Genres”).

[5] HMPPS Insights was created to bring together stakeholder groups from across the Criminal Justice System. The festival was a one-off event and was not intended to become an annual or bi-annual film festival.

[6] It is also worth noting that crime films are dispersed at various points across literary crime fiction events, although these are often retrospectives and limited in number – they are not the main point of such events but rather film-based add-ons.

[7] Note that as European nations will have been a production partner in more than one film the total will exceed the total number of crime films identified.

References

1. Altman, Rick. Film/Genre. BFI, 1999.

2. Baschiera, Stefano. “European Crime Cinema and the Auteur.” European Review, vol. 29, no. 5, 2021, pp. 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798720001143.

3. Chibnall, Steve, and Robert Murphy. “Parole Overdue: Releasing the British Crime Film into the Critical Community.” British Crime Cinema, edited by Steve Chibnall and Robert Murphy, Routledge, 1999, pp. 1–15.

4. de Valck, Marijke. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam UP, 2007.

5. Diego Maradona. Directed by Asif Kapadia, Film4, 2019.

6. “Genres.” IMDb Help Centre. 15 Dec. 2021, help.imdb.com/article/contribution/titles/genres/GZDRMS6R742JRGAG?ref_=pe_2610490_199225680_helpsrall.

7. Hunter, Russ. “Genre Film Festivals and Rethinking the Definition of ‘The Festival Film’” International Film Festivals: Contemporary Cultures and History Beyond Venice and Cannes, edited by Tricia Jenkins, I.B. Tauris, 2018, pp. 90–105.

8. Iordanova, Dina. “The Film Festival Network.” The Film Festival Reader, edited by Dina Iordanova, St.Andrews Film Studies, 2013, pp.109–26.

9. Leitch, Thomas. Crime Films. Cambridge UP, 2002.

10. “Marché du film: A Great Script!” Festival de Cannes, www.festival-cannes.com/en/qui-sommes-nous/marche-du-film-1. Accessed 7 Jan. 2022.

11. Petley, Julian. “The Lost Continent”, All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema, edited by Charles Barr, BFI, 1986, pp. 98–119.

12. Ruoff, Jeffrey. “Introduction: Programming Film Festivals.” Coming Soon to a Festival Near You: Programming Film Festivals, edited by Jeffrey Ruoff, St Andrews Film Studies, 2012, pp.1–2.

13. Stevens, Kirsten. “Across and In-between: Transcending Disciplinary Borders in Film Festival Studies”. Fusion Journal, no 14, 2018, pp.46–59.

14. Thompson, Kirsten Moana. Crime Films: Investigating the Scene. Wallflower Press, 2007.

Suggested Citation

Hunter, Russ. “Capturing European Crime: European Crime Cinema at European Film Festivals.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 22, 2021 pp. 31–41. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.22.02

Russ Hunter is a Senior Lecturer in Film & TV Studies at Northumbria University. His work focuses upon film festivals and genre film (particularly genre film festivals, Italian genre cinema and early horror cinema). He has written on numerous aspects of horror cinema, with an emphasis on European horror. With Stefano Baschiera he was the co-editor of Italian Horror Cinema and his scholarship has appeared in journals such as Studies in European Cinema, Film Studies, The Italianist and The Journal Italian of Cinema and Media Studies, as well as in collections such as International Film Festivals: Contemporary Cultures and History Beyond Venice and Cannes (2018), Italian Horror Cinema (2016), Screening the Undead: Vampires and Zombies in Film & Television (2013) and European Horror since 1945 (2012).