Cosmopolitan Crimes: Sebastian Schipper ’s Victoria (2015) and the Distribution of European Crime Films

Markus Schleich

Abstract

German crime films usually only find wide international circulation when they deal with either the two World Wars or the country’s unique position during the Cold War. Victoria (Sebastian Schipper, 2015) is an exception. The film, shot in one continuous take, tells the story of a young woman from Madrid who meets four local Berliners outside a nightclub in the middle of the night and ends up robbing a private bank with them. Without an established auteur or any sizeable star power attached to it, the film managed to travel widely within Europe, made possible by Creative Europe ’s funding schemes for distribution. The first section of the article examines the struggles of German crime films to cross the borders, despite the abundant national production of crime films, television series, and literature. The second section focuses on the importance of the distribution scheme that helped Victoria travel and explores how the policies of the MEDIA programme have shaped the European cinema landscape. In the third section, the paper examines how Victoria evokes images and discourses of European society such as disenfranchisement, solidarity, and precarity set in a cosmopolitan Berlin. By analysing the promotional texts, this final section explores how Victoria’s ideal combination of genre, auteurial ambitions and “added European value” granted the film access to support mechanisms which are usually out of reach for a film.

Article

Victoria and German Crime Films

While the label “Krimiland” (Wydra) is often used to describe the German appetite for all things crime, underlining the popularity of the genre withing the national borders, scholars did not fail to notice that German crime novels, films, or series do not travel well outside their domestic market and struggle to meet an international audience (Heuner).[1] Although crime series such as How to Sell Drugs Online (Fast) (Philipp Käßbohrer and Matthias Murmann, 2019) have introduced German crime fiction to international audiences, crime films—a consistently popular format in Germany that “has found its primary home on television” in the 1970s (Bergfelder 64)—rarely enjoy the same kind of exposure.[2] German films, as Thomas Elsässer points out, carry the mark of “the disasters of German history” (172). While scholarly attention for German films might have moved on from selected moments of German history (Bergfelder et al. 2), the country’s past continues to be the source material for contemporary German films and creates the most interest especially outside of Germany (Frey 179). This, in turn, supports to the hypothesis that German films tend to do well internationally when they contain “Hitler and the Berlin Wall” (Kürten). This holds true for the crime genre as well.

A look at the data collected by the European Audiovisual Observatory’s LUMIERE confirms that German films classified as crime by IMDb (Internet Movie Database) are more likely to meet an international audience when they engage with historical events. That is the case, for instance, of Sophie Scholl – The Final Days (Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage, Marc Rothermund, 2005)set during the Second World War, while Oscar-winning productions like The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006) and The Baader Meinhof Complex (Der Baader Meinhof Komplex, Uli Edel, 2008) are set at the height of the Cold War. Crime films production abounds on a national level; however, Victoria (Sebastian Schipper, 2015) is one of the very few that found success abroad without actively engaging in German history. Victoria is Sebastian Schipper’s fourth feature film and his prior films certainly fall into the category of German films that do not travel well internationally. According to the LUMIERE database, all his films were moderately successful in Germany through the arthouse circuit but failed to make an impact on non-national markets, reaching mainly German-speaking countries. Absolute Giganten (1999) was screened in Switzerland, Mitte Ende August (2009) graced a few screens in Austria, Ein Freund von mir (2006)—his most successful film before Victoria—was instead distributed both in Switzerland and Austria but collecting less than 15,000 total admissions on those markets despite the presence in the cast of Daniel Brühl and Jürgen Vogel, two very popular German actors. The distribution of Victoria followed a different path, reaching twenty-four European countries and achieving as many admissions outside of Germany as it did in its domestic market.

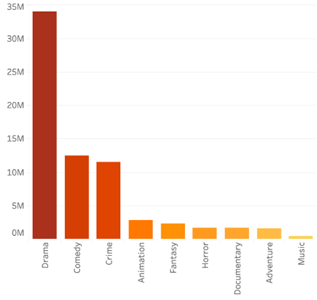

Shot in one continuous take, the film tells the story of a young Spanish woman, Victoria (Laia Costa), who has some time to spare between a long night of clubbing and her next shift as an underpaid barista. Victoria is a Spanish girl who recently moved to Berlin. She works in a cafe for less than minimum wage and wanders the city as a loner as she has no friends or acquaintances in the city. Her German is rudimentary, and she communicates primarily in English as is outlined in the very first scene when she orders drinks in the nightclub and interacts with her surroundings. She leaves the club in the early hours of the day, after dancing and drinking on her own. Outside the club, she meets four young men who are denied entry to the club. They are Sonne (“sun”; Frederick Lau), Boxer (Franz Rogowski), Blinker (Burak Yigit), and “Fuß” (“foot”; Max Mauff). They go on a stroll through the city, steal some beer from an off-license shop, and smoke marijuana on a rooftop. The mood changes when Sonne comes to pick them up. Sonne owes a favour to Andi (André Hennicke), a local gangster. Victoria learns that their mission is to rob a bank this morning. As Blinker is too intoxicated to participate, Sonne asks Victoria to fill his role. While the robbery goes smoothly, the police quickly catch up with them. The gang flees and a shootout ensues during which Fuß and Boxer are shot during the ensuing shootout, Sonne and Victoria can hide in an apartment. They can flee the scene, but Sonne has been hit by a bullet and dies as well. Alone and with the money from the robbery, Victoria leaves the hotel and wanders the streets of Berlin.

Figure 1. Laia Costa in Victoria. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, MonkeyBoy/Deutschfilm/RadicalMedia/WDR/Arte/The Match Factory, 2015. Screenshot.

In his review for The Hollywood Reporter, Stephen Dalton points out that while the story is not overly novel, the film makes up for this:Padding out a minimal 12-page script with heavily improvised dialogue, Victoria takes a while to emerge from its fuzzy-headed, freewheeling first act. But it repays our patience when it shifts gear from Richard Linklater-style talk-heavy Eurodrama to a heart-racing, adrenaline-pumped heist thriller.

This article examines how Victoria stands out in terms of distribution and promotion to identify factors that helped the film flourish, especially compared with another German crime film which managed to be internationally successful while being set in contemporary times, Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (Lola rennt, 1998). I would argue that the Victoria’s success is based on its technical execution and its European subtext which culminated in financial funding for its European distribution.

Crime Films within Creative Europe ’s Distribution Schemes

When analysing the promotion and cultural circulation of Victoria, it is important to look at the film’s theatrical distribution the role played by supranational support mechanisms such as those offered by Creative Europe MEDIA Programme must be considered. This also helps to contextualise how unique the films international performance.

Victoria secured EUR €443,400 from Creative Europe Programme (2014–2020) through the Selective Distribution scheme which seeks to support the theatrical distribution through marketing, branding, distribution, and exhibition of audiovisual works. The criteria on which the support is awarded include the film distribution strategies, quality of the content and relevance of its international/European/regional dimension (Creative Europe). Creative Europe calls for applications makes no explicit reference to genre, indicating a lack of importance in relation to applying and funding. The viability of the projects in terms of “theatrical distribution through marketing, branding, and exhibition of audiovisual works” is at the forefront. It aims to “encourage and support the wider non-national distribution of recent non-national European films by encouraging theatrical distributors to invest in promotion and adequate distribution” of European films, “thus improving the competitive position” of such films (Creative Europe).

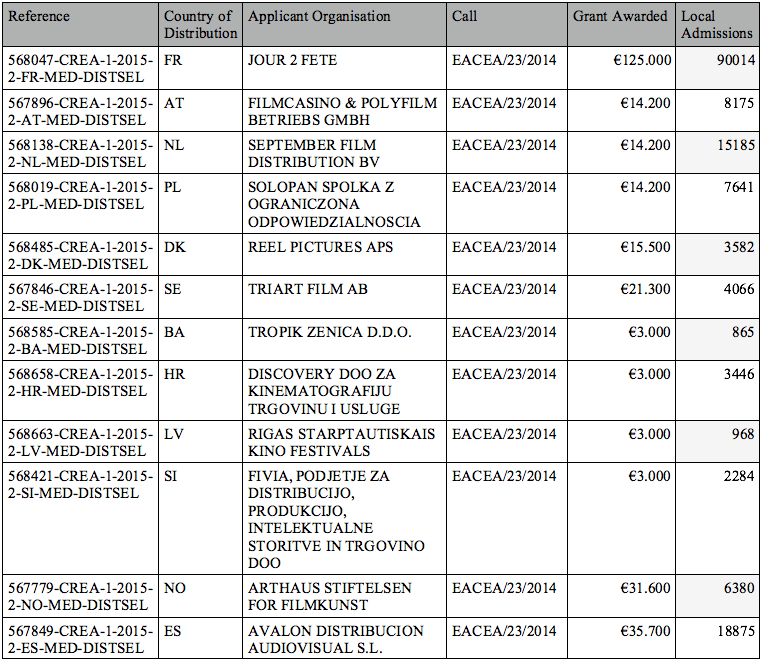

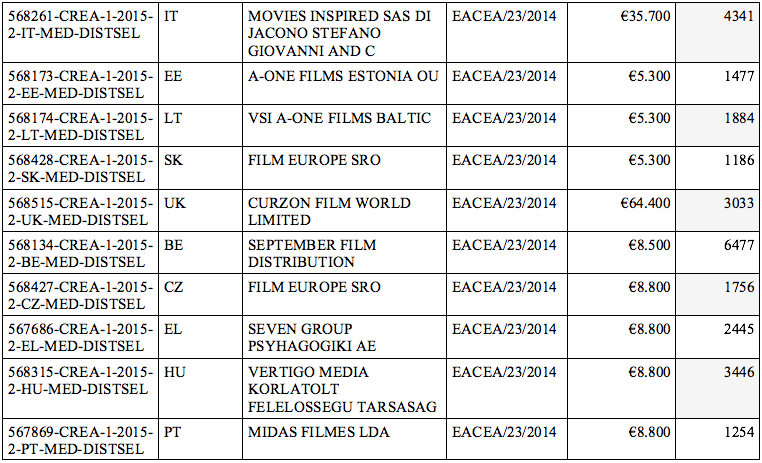

It is worth pointing that the policies from 2014–2020 saw a shift towards “high commercial and circulation potential” of the films applying for funding. The semantics of these policies stress the economic logic and “market-oriented perspective” which moves away from focusing solely on European Cultural Heritage (Bruell 23). Within this policy framework, Stefano Baschiera identifies “genre cinema as a commercial and cultural product. Genre films, in fact, tend to be commercially viable in the national market but struggle to reach a transnational audience, making them, on paper, a viable candidate for the transnational circulation support offered by Creative Europe” (30). [3] The question then is how does the economic potential of crime films translate into actual support? From 2014 to 2020, the MEDIA programme has seen 2,407 successful applications for the Selective Distribution scheme. That number is slightly misleading. Until 2018, each project needed at least seven local distributors but each of those had to apply individually. When the numbers are broken down by film and not by the distributor, only 152 films received funding, supported with total funding of approximately €66M. Breaking the applications down by genre, it becomes clear that drama, as a genre, receives 52% of the entire budget of €66M, followed by comedy with 12%, crime at 11%. Animation, adventure, horror, documentaries, and fantasy sit at around 5% each. There are some obvious reasons why drama secures most of the funding, given that the genre classification of drama is more inclusive than, for instance, crime or adventure.

Of the 152 films that received funding from 2014 to 2020, only twenty-two are crime films according to their classification on IMDb. And these films have something in common: the majority have an auteur attached to it: In the Fade (Aus dem Nichts,Fatih Akin, 2017), Dogman (Matteo Garrone, 2018), Dheepan (Jacques Audiard, 2015), Graduation (Bacalaureat,Cristian Mungiu, 2016), Human Capital (Il capitale umano,Paolo Virzì, 2013), A War (Krigen,Tobias Lindholm, 2015), Double Lover (L’Amant double,François Ozon, 2017), The Workshop (L’Atelier,Laurent Cantet, 2017), Mama Weed (La Daronne, Jean-Paul Salomé, 2020), the Unknown Girl (La Fille inconnue,Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne 2016), Nocturama (Bertrand Bonello, 2016), The House That Jack Built (Lars von Trier, 2018), Everybody Knows (Todos lo saben, Asghar Farhadi, 2019), and Utøya - July 22 (Utøya 22. Juli,Erik Poppe, 2018). The remaining films are either being based on successful source material—The Absent One (Fasandræberne,Mikkel Nørgard, 2014), A Conspiracy of Faith (Flaskepost fra P,Hans Petter Moland, 2016), Borders (Gräns,Ali Abbasi, 2018), Piranhas (La paranza dei bambini,Claudia Giovannesi, 2019), and Suburra (Stefano Solima, 2015)—or feature well-known actors—A Second Chance (En Chance Til, Susanne Bier, 2014) and A Bigger Splash (Luca Guadagnino, 2015).

Table 1. Genre affiliation of films supported by the selective distributed scheme (2014–2020).

Baschiera identifies the limited effort by European industries to invest in the promotion of popular crime films on a continental level, while arguing that the key factor that truly helps crime film to cross international borders is the presence of a recognisable auteurial figure (5).[4] Interestingly, an attached auteur does not only help crime films to travel but helps crime films to secure grants for international distribution. One could certainly argue that these crime films would probably have found an international audience regardless of the funding. Victoria’s success is even more astonishing when one considers that coproductions tend to circulate significantly more and better than nationally produced film. As Christian Grece notes in a report prepared by the European Audiovisual Observatory, in 2015 the “only two 100% nationally produced films” that made it on the list of the twenty films with the widest circulation in European cinemas were Victoria and Dheepan (19). Victoria is a film without any star power, the reputation of Schipper as a director is at best respectable and limited to the German-speaking part of Europe, and there is no source material that would attract viewers abroad. The commercial logic that benefitted the other crime films, does not apply here, yet Victoria did secure €443,400 in funding.

A Question of Technique: Victoria and Run Lola Run

Victoria has only been released to one European country that did not apply for distribution support: Curzon Film World in Ireland distributed the film and reached 1,981 admissions in 2016. This highlights the importance of these schemes for European crime films that might have auteurial ambitions, but no actual auteur attached to them.

Arguably, the biggest achievement lies in the technical execution of the film: with a runtime of 140 minutes and shot in a single continuous take, Victoria offers a very stylised cinematography, with the camera smoothly moving through large parts of Berlin framing car races, break-ins, and shootouts with the police as the narrative develops. It can hardly be denied that the technical aspect of the film contributes heavily to the circulation of the film. Even Germans scholars and critics, who tend to be lukewarm about domestic films, showed excitement about the success story of Victoria. Robert Reimer and Reinhard Zachau argue that this film shows that German films can once again compete globally: “the movie was filmed in one take of 140 minutes. German film seems once again to have come back as an important player in the international scene” (247). It might, however, be somewhat premature to conclude that technique accounts for the success alone. As Lutz Koepnick points out in his book The Long Take: Art Cinema and the Wondrous, the one-take is usually the “privileged stuff of cinephiles. They are designed for viewers passionate about the traditions of post-war art cinema and deeply suspicious about how technologies threaten the vibrant materiality of the analog experience” (9). One-take films do not translate into admissions as Russian Ark (Русский ковче, Alexander Sokurov, 2002) proved in the early 2000s. The technical virtuosity of this film has certainly helped it travel, but the popular element, represented by the crime genre, should not be overlooked.

This invites a comparison with the last German crime film that travelled widely without any connections to the German past. Run Lola Run shares a lot of Victoria’s features:Tom Tykwer’s film is also set in Berlin and follows a woman named Lola (Franka Potente) who needs to obtain 100,000 Deutschmarks in only twenty minutes to save the life of her boyfriend Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu) who is threatened by his employer, a local crime boss. Additionally, as the film tells its story in three-time loops that are all slightly different, Run Lola Run just as Victoria, a film shot in real time, stresses its own temporality (Rudolph 20).

But the similarities do not end there: Run Lola Run is also a German-only production which managed to get distributed widely. Most striking, however, is how this “entertaining but thoughtful thriller” combines a variety of media formats and techniques: “video, 35 mm stock, animation, digital effects, marking the passage of time with black-and-white photography for flashbacks and colour for flash-forwards” (Jäckel 31). The style has invited comparison to video games and “a feature-length music video” (Chappell 4). Tykwer, however, insists that his “arty mainstream” movie is first and foremost enjoyable, which some philosophical substance that allows for reflection afterwards (Jäckel 33).

Stephen Brockman notes that the film captured the mood of audiences especially in Europe as it “announced to the world the arrival of a dynamic young Germany synonymous with what many observers had begun to call the post-reunification ‘Berlin Republic’” (457). The film becomes a text that embodies the image of new Germany. Capitalising on the reputation that Berlin has gathered in the 1990s as the centre of techno culture and the annual Love Parade, the film is peppered with English lyrics and uses dialogue rather sparsely which made it especially attractive for international audiences, leading Miramax to sign a special agreement with X Filme, the production company of Run Lola Run, to secure exclusive first looks rights (Jäckel 33). For Brockman, the success of Run Lola Run has a lot do with how it “marked Berlin as a virtual territory for this generation of youth around the world” (458).

Berlin and the European Aspect

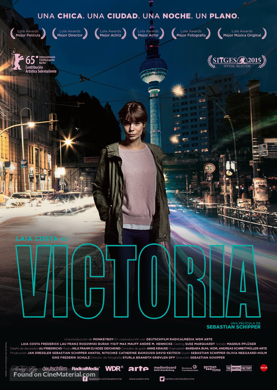

I will argue that Victoria employs a similar strategy: the film has been advertised with the tagline “One Girl, One City, One Night, One Take” even in Germany, which embodies the film’s strong European themes, crucial to understand how this film obtained funding for distribution. The film does represent a promising compromise between commercial viability, artistic ambitions, and current discourses on Europeanness, or, to quote Mariana Liz, “images of European society that will more clearly resonate with European citizens” (31). Sebastian Schipper has given numerous interviews in which he explained the tagline. Talking to Wolfgang Frömberg from Intro, Schipper explains how the bank robbery at night and the one-take don’t just create attention and awareness but just function as a vehicle to explore quieter themes, such as loneliness, solidarity, and precarity in a transnational Europe. Victoria and her new companions are all social and economic outsiders: Victoria is a foreigner who speaks no German, has made no friends, and works in a 4-Euro-per-hour job while Sonne and his pals loiter on the streets because they don ’t have the money for anything else. In the end, this is a film that, according to Schipper, very much “talks about money and privilege” embedded in a greater European context (Gamble). Victoria, the aforementioned “one girl”, comes from Spain which, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, carries a lot of significance. Spain, as a member of what has been coined “PIG states”—Portugal, Italy, Greece—in the late 1970s, and has been rebranded as “PIIGS” after 2008 to include financially struggling Ireland, saw much of its educated youth leave the country moving to the economically stronger countries in Central and Northern Europe. Schipper explicitly mentions this in the press kit released by Wolf Consultants:

In the general narrative, Germany is the rich, functioning straight-A student in Europe. Spain does not seem to be on the edge like Greece—but nevertheless, news about young Spanish people left with few to no perspectives has become commonplace. These are young people who don’t know what to do, where to go, or how to plan a future for themselves. […] For young people, life is still a huge challenge—especially if you don ’t come from a privileged background.

The setting of Berlin is essential here. In her article “Berlin the Virtual Global City”, Janet Ward argues: “Berlin ’s regained status as capital of the German nation is still being withheld, in part due to the urban regional strengths of the West German federalist system. […] In other words, Berlin has literally constructed […] itself […] in the shape of a European world city” (245). Berlin is barely a German city, something that Brockman also acknowledges when he speaks of the “Berlin Republic” in the context of Run Lola Run (457). Berlin is an international/European melting pot which makes for a perfect setting for a crime narrative that “represent[s] European landscapes and social realities to show-case the great geographical, social and cultural diversity that characterizes the continent”. (Dall’Asta, Levet, and Pagello 7).

Figure 2. Spanish Poster for Victoria. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, MonkeyBoy/Deutschfilm/RadicalMedia/WDR/Arte/The Match Factory, 2015.

Victoria ’s promotional texts constantly remind the viewer that this film takes place in Berlin, explicitly mentioning its setting and how much most of the personnel, apart from Victoria, identify as “Berliner”. Whereas the German posters only show Victoria ’s face, international posters, such as the Spanish one (Fig. 2), feature the TV Tower quite heavily. The French, English, North American, and Italian trailer all include clear architectural clues and dialogue that emphasise the importance of Berlin as a setting. That is by no means coincidental, as Susan Ingram and Katrina Stark conclude in World Film Locations: Berlin:

Despite the government’s best efforts to establish the Brandenburger Tor as the city’s post-Wende representative centre, the gate has so far proven unable to compete with the post-socialist TV Tower at Alexanderplatz, which was arguably the city’s most popular symbol at the outset of the 2010s. (7)

There are countless interviews that question Schipper's language choice which probably cost his film an Oscar nomination: it did not qualify for the Best Foreign Language Oscar category because the majority (51%) of the film is spoken in English (Aftab)—which, however, helped its international appeal and reflected the reality of Berlin where Europeans “run into other people from other countries and you speak this kind of English” (Whale). In most, if not all, interviews, Schipper repeatedly accentuates Berlin as a European hub and the fact that the heist is almost secondary to a much more universal theme. The decision to have a Spanish girl speak English to a German group came because the director wanted, according to his statements, to celebrate Europe and reflect the reality of the German capital as a cosmopolitan melting pot but also touch upon aspects of liminality within a fragile European enterprise:

It had to do with Berlin. […] But it also has to do with our times. I wanted this European aspect. I wanted this aspect of Berlin, being a little refuge for the people of Europe. The solidarity amongst young people is very touching, they stand for each other, they help each other, and of course, it’s no coincidence that she comes from Spain. […] I didn't want her to come from Greece, because that would make it super political, but obviously, she is coming from a place that is not doing so good, and she is coming to a country Germany, and we are doing really, really good [sic]. (Aftab)

This touches upon concepts of a transnational European identity that is heavily shaped by recent, especially economic, events: Victoria—a young Spaniard in Berlin—references a contemporary political and fiscal reality, and a crisis that has brought many young Europeans to Berlin. This, in turn, might reveal the films deeper subtext and also its auteurial ambitions: As Ib Bondebjerg et al. point out, “We are also influenced by mediated information and fictional or factual stories about reality” (24), a statement resonating with an often-quoted phrase by Joke Hermes: “popular cultural texts and practices are important because they provide much of the wool from which the social tapestry is knit” (11). The general hypothesis is that such “mediated encounters” with representations of other social and cultural realities through the consumption of popular (e.g., crime) narratives originating from other countries “enhance reflexive understanding of cultural others”, as being exposed to such works that are part of the everyday life of European citizens might challenge and enrich the audience’s sense of their own cultural identity (Bondebjerg et al. 5). Such experiences do not only promote the identification of commonalities among different cultures, but also elicit a reflection on the diversity that constitute the social and cultural fabric of Europe.

Thoughtful reflections on the nature of the European enterprise, however, do not necessarily make for a commercially viable film. In the introduction of the volume The Europeanness of European Cinema, Mary Harrod, Mariana Liz and Alissa Timoshkina postulate the thesis that a European film’s success often depends on capturing the mood of its European audience (4).[5] While not exactly comparable, this phenomenon can also be witnessed for television series. Discussions about the international success of Spanish hit series, Money Heist (La casa de Papel, Netflix, 2017–), about a group of anti-establishment bank robbers, often take notice that a show about robbers attacking capitalism and European banks is the reason for its captivated audience. Victoria does capture the mood of a post-2008-financial-crisis-crash Europe and the precarity shared by many young Europeans—who in this case must rob a bank out of despair and lack of opportunities. That might be just the kind of image of that clearly resonate with European citizens.

Conclusion

Crime feature films are rarely distributed outside their domestic market, even though the popularity and appeal of the genre become evident in the abundance of national productions. By analysing the data provided by Creative Europe’s “Selective Distribution” scheme and the European Audiovisual Observatory, a trend becomes apparent: crime films do travel when an auteurial figure is attached to it or a film can capitalise on popular source material, i.e., a successful crime novel. In Tatort Germany: The Curious Case of German-language Crime Fiction, Lynn M. Kutch and Todd Herzog observe that “the neglect of German language crime fiction on the international stage is nothing new”, which alludes to the fact that German crime tends to travel in the guise of historical drama, concerned with distinctive episodes of twentieth-century history and is therefore rarely perceived as crime (5).

Within the last twenty-five years, only two German films accomplished the feat of being distributed widely in Europe and beyond, and they share striking similarities. Victoria follows a strategy successfully employed by Run Lola Run in the late 1990s: fusing radical technique, a popular genre, and sociocultural reflections that resonated with the European zeitgeist. The latter aspect, a European subtext, is certainly more pronounced in Victoria and elevates the film above an exercise de style. By capturing the mood of its European audience—supported by Europe MEDIA’s Selected Distribution scheme—Victoria compensates for the lack of an attached auteur with clearly pronounced auteurial ambitions on both the stylistic and the narrative level which could prove to be a winning formula for other German crime films to unlock their international potential.

Acknowledgment

The research presented here has been financed by the research project DETECt — Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives (Horizon 2020, 2018–2021) [Grant agreement number 770151].

Notes

[1] The few publications devoted to this issue focus primarily on literature. One possible argument is that the dominance of foreign crime fiction (e.g., Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Wallace, the latter especially in its televised form) has for a long time occupied the German-speaking crime market, marginalising domestic crime fiction, and certainly influenced the opinion that crime fiction is not a German genre (Kutch and Herzog 5). German crime fiction is still largely neglected in non-German-speaking territories as there are few translations available. Furthermore, Germans appear to be rather negligent towards their domestic crime fiction. While there have been examples of highly popular and critically acclaimed crime novels written in German, they rarely are categorised as such. For his book, Euro Noir: The Pocket Essential Guide to European Crime Fiction, Film & TV, Barry Forshaw interviews Almuth Heuner who informed him that his plan to include authors such as Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Heinrich Böll, Hans Fallada, Peter Handke or Elfriede Jelinek in his study might prove problematic. In Germany, these authors are widely perceived as “literary writers” whose works are not associated with the genre of crime or mystery (109).

[2] European crime television series tend to travel exceptionally well in general (Hansen, Peacock, and Turnbull).

[3] In 2019, the European Audiovisual Observatory recorded 7.821 European feature films, meaning that there was at least one admission in one cinema, including the domestic territory (Gilles). At first glance, the international distribution of European export films appears healthy with 3.954 films (50%) screened outside the domestic market. However, the data also highlight a less convincing European distribution pattern. 28% (or 2.210) were screened in only one territory outside their home market. 8.5% (667 films) were released on two non-national markets. Only 5.2% (411 films) were released in six or more international markets, and this 5.2% comprise almost 80% of all European admissions for European films (Simone). Based on this, we may assume that European films travel, but most of them do not travel widely. Furthermore, the number of European films that are released outside their domestic territory may be rising, but theatrical admissions to these films are in decline.

[4] There is an interesting similarity between the perception of widely distributed crime films as auteur films and internationally successful German crime novels as being written by German highbrow authors (Forshaw 109).

[5] The authors draw drawing on the success of Cédric Klapisch ’s Pot Luck (L ’auberge Espagnole) from 2002. This film presents a somewhat romanticised version of Europe: a group of European Erasmus students lives in a shared flat in Barcelona, eventually becoming friends. All flatmates showcase their specific national characteristics hence being united in diversity, which is the official slogan of the European Union after all. Harrod, Liz and Timoshkina make a convincing case that this film was so successful because it sold a narrative based on the positive mood associated with the European Union at the time. A story of very different people from various European countries who come together under the roof of one flat which represents the European Union, something that is also highlighted by the fact that all the protagonists study in Barcelona funded by a European exchange program, and of course, speak English (4).

References

1. The Absent One [Fasandræberne]. Directed by Mikkel Nørgard, Det Danske Filminstitut/ Eurimages/Film Väst/TV2 Danmark/Zentropa, 2014.

2. Absolute Giganten. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, X-Filme Creative Pool, 1999.

3. Aftab, Kaleeb. “Director Sebastian Schipper on German film Victoria that Was All Shot in a Single Continuous Take.” Independent,13 March2016, www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/sebastian-schipper-on-german-film-victoria-that-was-all-shot-in-a-single-continuous-take-a6925271.html.

4. The Baader Meinhof Complex [Der Baader Meinhof Komplex]. Directed by Uli Edel, Constantin Film Produktion, 2008.

5. Baschiera, Stefano. “European Crime Cinema and the Auteur.” European Review, vol. 29, no. 5, 2021, pp. 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798720001143.

6. Baschiera, Stefano, and Markus Schleich. “Cultural Mobility through Narrative Media Production in the European Cultural Space.” DETECt, June 2021, www.detect-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/D4.3-Final.pdf.

7. A Bigger Splash. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, Frenesy Film Company/Cota Film, 2015.

8. Borders [Gräns]. Directed by Ali Abbasi, META Film/Black Spark Film/TV Karnfilm, 2018.

9. Bergfelder, Tim. “Introduction.” The German Cinema Book,edited by Tim Bergfelder, Erica Carter, Deniz Göktürk and Claudia Sandberg, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp. 15–7.

10. Bergfelder, Tim, Erica Carter, Deniz Göktürk, and Claudia Sandberg. “General Introduction.” The German Cinema Book,edited by Tim Bergfelder, Erica Carter, Deniz Göktürk and Claudia Sandberg, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp. 1–10.

11. Brockmann, Stephen. A Critical History of German Film. Camden House, 2020.

12. Bruell, Cornelia. Creative Europe 2014–2020: A New Programme - A New Cultural Policy as Well? Ifa, 2013.

13. Bondebjerg, Ib, et al. Transnational European Television Drama: Production, Genres and Audiences. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017

14. Chappell, Crissa-Jean. “Movie Maid: Crissa-Jean Chappell Tracks Run Lola Run.” Film Comment, vol. 35, no. 5, 1999, p. 4.

15. Crece, Christian. “The Circulation of EU Non-national Films. A Sample Study: Cinema, Television and Transactional Video On-demand.” European Audiovisual Observatory, Nov. 2017, rm.coe.int/the-circulation-of-eu-non-national-films-cinema-tv-and-tvod/16808b35a2.

16. Creative Europe. “Funding Opportunities.” Ec.Europa.eu,2019, www.eacea.ec.europa.eu/grants/2014-2020/creative-europe/support-distribution-non-national-films-distribution-selective-scheme-2020_en.

17. A Conspiracy of Faith [Flaskepost fra P]. Directed by Hans Petter Moland, Det Danske Filminstitut/Eurimages/Film Väst/TV2 Danmark/Zentropa, 2016.

18. Dall ’Asta, Monica, Natcha Levet, and Federico Pagello. “Glocality and Cosmopolitanism in European Crime Narratives.” Academic Quarter, no. 22, Spring 2021, pp. 1–18, https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.academicquarter.vi22.6598.

19. Dalton, Stephen. “Victoria: Berlin Review.” Hollywood Reporter, 7 Feb. 2015, www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/victoria-berlin-review-770825.

20. Dheepan. Directed by Jacques Audiard, Canal+, 2015.

21. Dogman. Directed by Matteo Garrone, Archimede/Le Pacte/Rai Cinema, 2018.

22. Double Lover [L’Amant double]. Directed by François Ozon, Mandarin Cinéma/Scope Pictures, 2017.

23. Ein Freund von mir. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, X-Filme Creative Pool, 2006.

24. Eduqas. “Victoria (2015, Sebastian Schipper, Germany).” EDUQUAS, 2015. https://resource.download.wjec.co.uk/vtc/2016-17/16-17_1-19/_eng/victoria.pdf.

25. Elsaesser, Thomas. “The German Cinema as Image and Idea.” Encyclopedia of European Cinema, edited by Ginette Vincendeau, Cassell/British Film Institute, 1995, pp. 172–5.

26. Everybody knows [Todos lo Saben]. Directed by Asghar Farhadi, Memento Films/Morena Films/Lucky Red, 2019.

27. Fontaine, Gilles. “Audiovisual Fiction Production in the European Union. 2019 Edition.” European Audiovisual Observatory, Feb. 2020, rm.coe.int/audiovisual-fiction-production-in-the-eu-2019-edition/16809cfdda.

28. Forshaw, Barry. Euro Noir: The Pocket Essential Guide to European Crime Fiction, Film & TV. Pocket Essentials, 2014.

29. Frömberg, Wolfgang. “Intro trifft Victoria. Ein Take, ein Interview.” Intro,11 June 2015. https://www.intro.de/tv/kultur/intro-trifft-victoria-ein-take-ein-interview. Accessed 30 Oct. 2021.

30. Frey, Mattias. Postwall German Cinema. History, Film History and Cinephilia. Berghahn, 2015.

31. Gamble, Patrick. “Sebastian Schipper on Single-shot Crime Flick Victoria.” The Skinny, 25 March2016, www.theskinny.co.uk/film/interviews/sebastian-schipper-victoria-berlin.

32. The Graduation [Bacalaureat]. Directed by Cristian Mungiu, Why Not Productions/Les Films du Fleuve/France 3 Cinéma, 2016.

33. Heuner, Almuth. “Germany’s Crime and Mystery Scene.” World Literature Today, vol. 85, no. 3, 2011, pp. 16–17, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41310426.

34. Harrod, Mary, Mariana Liz, and Alissa Timoshkina. The Europeanness of European Cinema: Identity, Meaning, Globalization. I. B. Tauris, 2015.

35. Hermes, Joke. Re-reading Popular Culture. Blackwell Publishing, 2005.36. Herold, Anna, and Claudia Golser. “Reconciling Economic and Cultural Goals in Film Policy Propositions from Europe.” Reconceptualizing Film Policies, edited by Nolwenn Mingant and Cecilia Tirtaine, Routledge, 2018, pp. 198–204.

37. The House That Jack Built. Directed by Lars von Trier, Zentropa/Film i Väst/Eurimages/ Nordisk Film/Les films du losange, 2018.

38. How to Sell Drugs Online (Fast). Created by Philipp Käßbohrer and Matthias Murmann. Netflix, 2019–.

39. Howard, Jack. “Victoria: An Interview with Sebastian Schipper.” Berlin Film Journal,2015. http://berlinfilmjournal.com/2015/02/victoria-an-interview-with-sebastian-schipper/. Accessed 30 Oct. 2021.

40. In the Fade [Aus dem Nichts]. Directed by Fatih Akin, Bombero International/Warner/ Macassar Productions/Pathé Film/Dorje Film/Corazón International, 2017.

41. Ingram, Susan, and Katrina Stark. World Film Locations: Berlin. Intellect, 2012.

42. Jäckel, Anne. European Film Industries. BFI, 2004.

43. Hansen, Kim Toft, Steven Peacock, and Sue Turnbull (eds.). European TV Crime Drama and Beyond.Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

44. Human Capital [Il capitale umano]. Directed by Paolo Virzì, Indiana Production Company/Rai Cinema/Manny Films, 2013.

45. Koepnick, Lutz. The Long Take: Art Cinema and the Wondrous. U of Minnesota P, 2017.

46. Kürten, Jochen. “German Cinema Moves Beyond Nazis and the Cold War to Reinvent Its Image Abroad.” DW, 30 June 2016, www.dw.com/en/german-cinema-moves-beyond-nazis-and-the-cold-war-to-reinvent-its-image-abroad/a-19364483.

47. Kutch, Lynn M., and Todd Herzog. Tatort Germany: The Curious Case of German-language Crime Fiction. Camden House, 2014.

48. The Lives of Others [Das Leben der anderen]. Directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, Bayerischer Rundfunk/Arte /Creado Film, 2006.

49. Liz, Mariana. Euro-Visions Europe in Contemporary Cinema. Bloomsbury, 2016.

50. Mama Weed [La Daronne]. Directed by Jean-Paul Salomé, Les Films du Lendemain/La Boétie Films/Scope Pictures, 2020.

51. Money Heist [La casa de papel]. Created by Álex Pina.Antena 3/Netflix, 2017.

52. Mitte Ende August. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, X-Filme Creative Pool, 2008.

53. Nocturama. Directed by Bertrand Bonello, Wild Bunch/Arte, 2016.

54. Pagello, Federico. “Images of the European Crisis: Populism in Contemporary European Crime TV series”. European Review, 20 July 2020, pp. 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798720001167.

55. Piranhas [La paranza dei bambini]. Directed by Claudia Giovannesi, Palomar/Vision Distribution, 2019.

56. Pot Luck [L ’auberge Espagnole]. Directed by Cédric Klapisch, Ce Qui Me Meut France 2 Cinéma Mate Production, 2002.

57. Reimer, Robert, and Reinhard Zachau. German Culture through Film: An Introduction to German Cinema. Hackett Publishing, 2017.

58. Rudolph, Eric. “Production Slate: A Runaway Hit.” American Cinematographer, vol. 20, no. 6, 1999, pp. 20–6.

59. Russian Ark [Русский ковче].Directed by Alexander Sokurov, Seville Pictures, 2002.

60. A Second Chance [En Chance Til]. Directed by Susanne Bier, Zentropa, 2014.

61. Simone, Patrizia. “The Circulation of European Films in Non-national Markets. Key Figures 2019’. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2021, rm.coe.int/export-2020-en-final-online-version/1680a1e35f.

62. Sophie Scholl – The Final Days.Directed by Marc Rothermund, Warner Home, 2005.

63. Suburra. Directed by Stefano Solima, Cattleya/Rai Cinema, 2015.

64. The Unknown Girl [La Fille inconnue]. Directed by Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Les Films du Fleuve/Archipel 35/Savage Film, 2016.

65. Utøya - July 22 [Utøya 22. Juli]. Directed by Erik Poppe, Paradox Film 7, 2018.

66. Victoria. Directed by Sebastian Schipper, MonkeyBoy/Deutschfilm/RadicalMedia/WDR/ Arte/The Match Factory, 2015.

67. A War [Krigen]. Directed by Tobias Lindholm, AZ Celtic Films/Nordisk Film Production, 2015.

68. Ward, Janet. “Berlin, the Virtual Global City.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014, pp. 239–56, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412904044819.

69. Whale, Chase. “A Conversation with Sebastian Schipper.” ChaseWhale.com, 20. Sept. 2015, www.chasewhale.com/interviews/sebastianschipper.

70. Wolf Consultants. “Victoria: A Film by Sebastian Schipper.” German Films, 2015. www.german-films.de/fileadmin/mediapool/pdf/Press_Books/VictoriaPressbook.pdf.

71. The Workshop [L’Atelier]. Directed by Laurent Cantet, Archipel 35/Archipel 33, 2017.

72. Wydra, Thilo. “Spannung muss sein. Deutschland, Krimiland.” Tagesspiegel,12 Dec. 2010, www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/medien/sapnnung-muss-sein-deutschland-krimiland/3620846.html.

Suggested Citation

Schleich, Markus. “Cosmopolitan Crimes: Sebastian Schipper ’s Victoria (2015) and the Distribution of European Crime Films.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 22, 2021 pp. 66–81. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.22.05

Markus Schleich has published articles on serial narration, quality television and the European film industry in journals and edited collections and coedited various books. With Jonas Nesselhauf, he coauthored an introduction to Television series for the German UTB-series (Fernsehserien. Geschichte – Theorie – Narration, UTB 2016). He holds a PhD from the University of the Saar in comparative media studies with a thesis on the relationship between popular music and mythology. From 2019 to 2021, he was a research fellow with the Horizon 2020 project DETECt – Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narrative. He is internal examiner for German at Queen’s University Belfast.