On the Cultural Circulation of Contemporary European Crime Cinema

Editorial

Stefano Baschiera

Considering the transnational prominence of European cinema, European crime films present an interesting case. As a genre, crime “is clearly the most popular genre across Europe for novels, television series and films”, and crime fiction productions are abundant on a national level in most European countries (Bondebjerg et al. 223). Crime fiction, therefore, appears as the genre most able to facilitate transborder cultural exchange and communicate “Europeanness” at local, national, regional, and transnational levels. This is surely the case of television productions where “crime drama seems to be a powerful, cross-cultural phenomenon with the noteworthy possibility of travelling internationally” (Hansen et al. 3). However, while crime novels and television series have been receiving much critical attention—especially within the context of Nordic Noir—crime films are absent from most of the scholarly discussions and struggle to gain cross-border popularity. It can be argued that crime drama on television has profited from a changed transnational production and distribution culture which has not benefited European crime films in the same way.

Developing from the research topics addressed by the DETECt (Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives) project, this twenty-second issue of Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media aims to investigate the understanding and problematic genrefication of contemporary European crime cinema when it crosses the national borders. Consequently, the contributions in this issue, through a media industries approach, place the theatrical distribution at the centre of genre analysis, while addressing thematic and productive features as well as the changing cultural capital of crime productions.

In recent years, scholars have become increasingly interested in the study of European cinema from an industrial perspective. From the works of the early 2000s by Anne Jäckel, Tim Bergfelder and Thomas Elsaesser to the most recent research carried out by Petr Szczepanik and Patrik Vonderau and by Mariana Liz, the scholarly attention towards different components of the production value chain within the European audiovisual context have added a new dimension to an area of investigation traditionally characterised by textual analysis and a national approach. Several academic publications focusing on the likes of screen policies, co-production agreements, film festivals, star system, marketing and the exhibition sector linked and intertwined with the plethora of reports and analyses commissioned by public players in the audiovisual market to grasp the development and social impact of the European audiovisual industry. A recurring argument present in these publications is that film distribution is the Achilles’ heel of the European film industry. Not only there is a strong agreement on this point that can be found, for instance, in works by Jäckel, Andrew Higson, and Virginia Crisp and Gabriel Menotti Gonring, but such statement is also present across decades of analytical reports and in the different European policies in support of the audiovisual industry, starting with the introduction of the MEDIA programme in the 1990s and all its successful iterations.

Across these studies, ample evidence exists to prove that the film industry in Europe is very wealthy from a production perspective, with the number of films produced per year that is in constant growth (averaging a production of around 1,250 films per year) and able to challenge the production outcomes of the US. The problem is that only a small percentage of the films made in Europe manage to cross the national borders and meet an international audience. If we consider, for instance, the data collected by the European Audiovisual Observatory for the year 2019 (the last pre-pandemic) 61% of the films exported captured fewer than 1,000 admissions in non-national markets and “[o]verall, only 10% of the 3954 export films of 2019 travelled to six or more countries, capturing the majority of European admissions worldwide, among them, only 31 non-national European films generated at least 1 million ticket sales outside their home markets” (Simone 11).

As Higson argues in his analysis of the data collected as part of the MeCETES research project, “European films, both national and non-national, account for 65% of all films receiving a theatrical distribution in Europe in the period 2005–2015, but those films generated only 33% of all admissions. By contrast, only 17% of the films available in European cinemas were US-led productions, but they accounted for a huge 64% of all admissions” (Higson 307–8). Therefore, despite the cultural circulation of audiovisual products (and the goal of a common European market) has constantly been a key priority task of the Creative Europe–MEDIA Programme, European audiences rarely watch non-national European products, so films that are produced outside their own country. This is clear also in the data analysis conducted by Georgios Alaveras, Estrella Gomez‐Herrera and Bertin Martens, which takes into consideration a twenty-year timescale of distribution: “EU-produced films account for 44% of all titles available in EU cinema over the period 1994–2014 but only 29% of all admissions. US films account for only 45% of titles and 67% of admissions. One important reason is that US films are more widely available in the EU than EU films” (659).

This recurring inability to have European films easily circulate among the state members and being competitive in non-national markets, mainly against American productions, is clearly problematic from different perspectives. First, from a cultural perspective, it compromises films’ potential as “identity builders”. Through self-representation of stories, values, spaces, social and political debates, the audiovisual products have been considered as an important vehicle of reflection on a collective identity embracing the EU’s motto of “unity in diversity”. The introduction by the European Commission of the LUX Prize is a clear example of how the circulation of cultural products is important to spread European identity and values (Baschiera and Di Chiara). Second, from an industrial perspective, the problematic international circulation underlines the shortcomings and questions the sustainability of a very prolific production system that cannot find an audience. This is even more significant considering the plethora of public support (at supranational, national, and regional level) and soft money available to boost production within the European territories (Milla et al.), which not only further deepens the gap with the scarce support to distribution but also seldom considers audiences’ tastes and demands. Despite there is a general agreement on the importance of distribution and cross-border circulation for the future of the European audiovisual sector—and several screen policies are aimed at addressing it—the funding initiatives to support them is still scarce if compared to those supporting production. Interesting for this special issue, the number of academic investigations dedicated to film distribution is low, making it a significantly under-researched area within screen industries, as also pointed out by Crisp and Menotti Gonring, Julia Knight and Peter Thomas, and Dina Iordanova and Stuart Cunningham among others.

While the recent technological advancements in online distribution are investigated by scholars looking at the impact of the digital distribution and the new channels of formal and informal circulation (Lobato), and while we have been witnessing new significant developments in the study of film festivals, audiences and (albeit in a very minor way) film marketing, theatrical distribution remains a subject mainly approached by industrial reports instead of scholarly research. However, I would argue that the distribution is a key element to understand the state of European cinema as a cultural industry, concerning its contribution to the development and understanding of genre cinema. From the involvement of broadcasters and distributors at the early stages of the production, to the role played by art-cinema venues in the visibility of European cinema, cultural circulation shapes the understanding of the genre and, through gatekeeping and audience expectations, addresses its categorisation, evolution, and canon. As Ramon Lobato and Mark David Ryan argue, “[a]ttention to the circulation of texts as material commodities in cultural markets, and to the structural and economic forces shaping movie genres as textual formations, industrial categories and production templates, can produce new models for genre analysis” (191).

Among the windows of film exploitation, this special issue focuses its attention on theatrical circulation of texts because of the cultural capital still strongly associated with it, and because it allows us to map the international reach of a film, also considering its marketing and visibility.

Which European Films Do Travel?

Unsurprisingly, most films that travel beyond the national market are from the “Big 5” of European production countries (France, Spain, Germany, UK, Italy), which therefore confirm their quantitative dominance in production also in the cross-border distribution (European Audiovisual Observatory). In this context, the UK is the main force because of its involvement in cross-Atlantic co-productions, which allows the making of films with a budget impossible to achieve for other nations. French and British films strongly dominate the export at the non-national level, to the extent that in 2019 they “accounted for 37% of export films and 62% of total export admissions to European films” (Simone 3). A closer look at the international outreach of the productions of the two countries reveals how UK films comprise “44% of total export admissions to European films worldwide, despite representing only 13% of European film exports on release in 2019. Conversely, French export films (24% of export films on release) performed comparatively poorly, accounting for only 18% of global non-national admissions to European films” (Simone 3). Productions of the “Big 5” have the advantage of a sizeable internal market (allowing the making of ambitious projects) and the possibility to rely on a series of infrastructures, networking, and established partnerships, which make them extremely competitive in securing supranational and national support. For instance, films made by the big five are by far (and unsurprisingly) the main beneficiaries of the support of distribution offered by the Creative Europe Programme (Baschiera and Schleich). According to the findings of the previously mentioned MeCETES project (Huw; Higson), the kind of European films that travel successfully (i.e., that achieve at least one million admissions in non-national markets) can be regrouped in five categories:

transatlantic European films which feature European characters, stories, and settings, but are made with American money and creative talent;

auteur-driven dramas, where the director’s name is the main bankable asset, alongside the reliance on a festival run;

mid-budget “middlebrow” comedies and dramas, characterised by British productions, usually shot in English with recognisable international stars;

family films and animations, which tend to be made in co-production agreements;

documentaries, usually nature non-fiction films.

Although crime is not named in this list, we can understand how the genre is often embodied in the first category through several examples of transatlantic English-speaking crime co-productions involving an international star. The most recent of this category is the UK, Norway, China, Canada, US, and France co-production Cold Pursuit (Hans Petter Moland, 2018) featuring Liam Neeson. To some extent, this film epitomised an ongoing trend within European crime narratives—aiming to an international audience through a focus on the action, violence, and the spectacular—to the point that it could be considered as a sub-genre on its own term. However, a bigger incidence in the circulation of a crime film is given by an established auteur associated with the production. If we consider the major factors that make a European film travel (budget, marketing and distribution, familiarity with the cultural content), the presence of a recognisable director is key to reach a significant non-national circulation. This happens for three reasons. First, the circulation of European films on non-national markets mainly occurs within an “arthouse” exhibition circuit. This is particularly true if the film circulates with subtitles, and it is not an English-language production. Within such exhibition sector, the director’s name works as the main marketing tool, dictating audience expectations. Second, and to some extent linked to the first point, films by established directors consider the film festival circuits as a fundamental venue for their international circulation, which allows them to be selected by agents and distributors for different European markets. Finally, most European crime films that are present in non-national markets are international co-productions, which significantly benefit from having a bankable director’s name associated with the project to find international (and supranational) finance support. Therefore, as I discussed elsewhere, the association between crime and auteur cinema is very strong in the European context, especially when the film manages to cross the national borders, and problematise the very understanding of the crime genre and its cultural capital, from the national “quality” productions to the art-house circuit distribution (Baschiera).

The Circulation of European Crime Films: The Mark of the Auteur

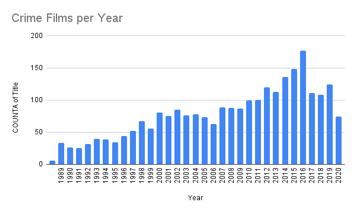

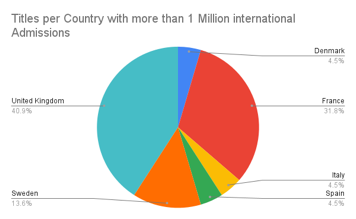

The production of crime films is abundant on a national level in most European countries, with 2,559 crime films produced between 1989–2020 according to IMDb (Fig. 1). Despite the popularity of the genre, these productions follow the same fate as other European feature films in terms of problematic access to non-national markets and difficulty in meeting a wider audience. Most European crime films fail to reach over six non-national markets, with a very low number of productions that achieve one million admissions outside the country of production (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 (above): Crime films per country according to IMDb. Figure 2 (below): Only 1% of all crime films reached over one million admissions internationally. Based on data from the LUMIERE Project, only six countries have achieved this. DETECt – Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives, 2018–2021.

Interestingly, the occurrence of the rare international success is characterised by factors that have little to do with the genre belonging, making the crime somehow incidental for their international appeal. While crime as a label can be seen as a viable component helping a film to go to production, this occurs mainly for the popularity of the genre within the national markets but does not translate into an ability to travel well.

To grasp the key features that make a crime film travel across Europe, meeting different audiences, we can consider the top five crime films, according to IMDb ranking, for each of the “Big 5” nations of European cinema.[1] This choice is made to capture the films that are the most popular for an international audience, considering the productive dominance of the UK, France, Spain, Germany, and Italy, and acknowledging that the position of those films as ranked by IMDb users, already implies a degree of cultural circulation.

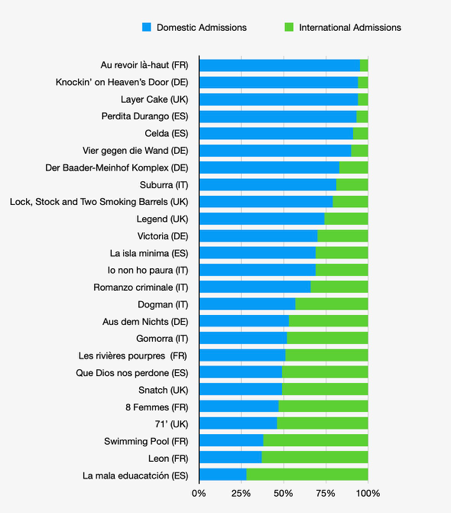

Figure 3: Domestic vs international admissions of the top five crime films for each of the “Big 5” nations. Data collected from LUMIERE project database. DETECt – Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives, 2018–2021.

Out of the twenty-five films selected, only nine are not the result of co-production agreements, three films each for Germany (Victoria, Sebastian Schipper, 2015; Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, Thomas Jahn, 1997; Four Against the Bank/Vier gegen die Bank, Wolfgang Petersen, 2016), Spain (Bad Education/La mala educación Pedro Almodóvar, 2004; Marhsland/Isla minima, Alberto Rodriguez, 2014; May God Save Us/Que dios nos perdone Rodrigo Sorogoyen, 2016) and UK (Layer Cake, Matthew Vaughn, 2004; ’71, Yann Demange, 2014; Lock and Stock and Two Smoking Barrels,Guy Ritchie, 1998), while all films from Italy and France come from transnational production.

The benchmark to establish the reliance of crime films on non-national markets in respect to other productions is roughly based on the average European admissions by using the 2019 data of the European observatory showing that, “[o]n a cumulative level, European films generated 59% of their total admissions in their respective national markets” (Simone).[2]

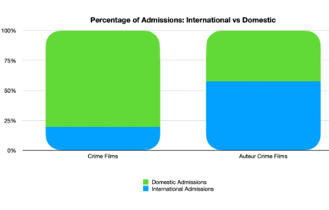

Figure 4. Percentage of domestic vs international admissions of the top five crime films for each of the “Big 5” nations. “Auteur crime films” have an award-winning director associated with them.

Admission data from LUMIERE project database. DETECt – Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives, 2018–2021.

Looking at the data (Fig. 3 and 4), and against this benchmark, we can grasp how crime films without a recognisable auteurial figure (understood here as an award-winning director) generate most of their admissions in the national market, reaching peaks of over 90%. This support the understanding that crime can be considered as a national genre, whose international scope has more to do with its strong presence in all European national markets than its ability to have an impact on non-national ones. Even for a film industry like the UK’s, which achieves most of its admissions in the non-national market, crime films struggle to travel. Things change when films are the work of an established auteur. On those occasions, as we can see from Figure 4, the national market admissions drop quite consistently under 61%, with the outlier of Almodovar’s Bad Education, which has only 25% of admissions in Spain despite, as previously mentioned, being one of the few films to be an exclusively national production.

To some extent, the main exception to such “auteur rule” is ’71, a film that per se is an outlier of IMDb genre labelling. The British film is the work of a French debutant director whose career then developed as a TV producer. However, ‘71 benefited from the Berlin festival selection. While it is undoubted that a well-known director associated with any European film significantly helps the circulation, and that more data collection and comparative research is needed, I would argue that, among popular genres, and therefore with the exclusion of the broad category of drama, crime is where this occurs more significantly. The role played by the director’s name is even more significant when the films have not been shot in English and, therefore, the association with art cinema, because of the use of subtitles, is considerably stronger. This is the case, for instance, of two of the most successful European crime films, in terms of non-national theatrical distribution, since the start of the new millennium: Volver (Pedro Almodóvar, Spain, 2006), with 6,550,216 European non-national admissions, and Gomorrah (Gomorra, Matteo Garrone, Italy, 2008), with 1,742,502. The latter is an interesting example because alongside the presence of a promising auteur, at the time not yet established at the international level, the film could benefit from another key feature in aid of an international distribution, that is the presence of a well-known source material.

Figure 5: Volver (Pedro Almodóvar, 2006). El Deseo, 2006. Screenshot.

Among the European crime films not shot in English and which widely and successfully circulated in non-national market, there is only a key example of a film that did not rely on a bankable director, or star: Niels Arden Oplev’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Män som hatar kvinnor, 2009), which benefitted mainly from the outstanding global success of Stieg Larsonn’s novel. If we consider the distribution data of 2019—the last year on record before the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—as a snapshot of the status of European crime films in non-national territories, it is possible to grasp how the trend already noticed within the top five crime films for the “Big 5” countries continues to persist. Among the top fifty films released in non-national European markets in 2019, only four have been labelled as crime by IMDb: The Sisters Brothers (Les Frères Sisters, Jacques Audiard, 2018), Everybody Knows (Todos lo saben, Asghar Farhadi, 2018), The Traitor (Il traditore, Marco Bellocchio, 2019), Cold Pursuit. Therefore, in a year when 124 crime films were produced in Europe, only four of them managed to have a significant presence outside the national borders and, among them, only Cold Pursuit achieved more than one million admissions in non-national markets. These four films somehow represent the condition of European crime cinema in non-national markets, between the ambiguous geographical, generic and narrative belonging of Cold Pursuit (set in Colorado and shot in Canada) and the art-house “quality” direction of The Traitor. Moreover, looking at the genre belonging of the top fifty films according to the non-national admissions, it may come as a surprise that a genre usually associated with national markets like comedy is far more present than crime, making the list seventeenth times (usually in association with other genres, like “comedy, drama, fantasy”).

Despite the international appeal of the genre, European crime cinema as popular culture lies mainly within the national borders to the extent that it becomes “European” only when associated with an auteurial figure. When films cross the borders, their cultural capital changes because of the place of exhibition. This leads to the predominance of an auteur-centric approach for its understanding, which compromises any possibility of industrial and critical genrefication within a European context (Baschiera). The role of the auteur name is also one of the most recurring topics emerging from the five articles of this issue and their attempt to address contemporary European cinema when it crosses the national borders.

In his article “DETECting the ‘Noirification’ of European Popular Narratives Across Film, Fiction and Television” included in this issue of Alphaville, Federico Pagello engages with the research carried out within the DETECt project to consider the use of the “noir” label in the context of the recent development of a “European quality crime cinema”. By analysing the transnational distribution of contemporary national Italian cinema, and the impact of an intermedial approach, Pagello considers the centrality of crime narratives within contemporary creative industries also as a consequence of a process of cultural legitimisation.

The genre’s cultural capital is also at the centre of the article by Russ Hunter, “Capturing European Crime: European Crime Cinema at European Film Festivals”, which analyses crime narratives within the festival circuit. By looking at the films programmed at the film festivals in Cannes, Venice and Berlin over a five-year period Hunter not only reflects on the European production and exhibition of the genre but also engages with the problematic definition of crime film itself, and its national connotations.

Among different intertwining of crime narrative within a national context, Richard Gallagher’s article “The Troubles Crime Thriller and the Future of Films about Northern Ireland” considers changes in screen policies and the appeal to an international audience in order to frame the development of Northern Irish productions engaging with “Troubles stories”. According to Gallagher, recent films such as Shadow Dancer (James Marsh, 2012), A Belfast Story (Nathan Todd, 2013) and The Truth Commissioner (Declan Recks, 2016) provide a depiction of the region and its history while adopting a series of features from popular genres, in particular crime and thriller, meeting in this way the demands of market-driven cultural policies.

The last two contributions of this issue are instead dedicated to specific case studies, following their transnational marketing and distribution. Accordingly, Damiano Garofalo’s “The Distribution and Promotion of Dogman (2018) in the United States” relies on interviews with distributors and on primary sources to grasp how Matteo Garrone’s film circulated within the American market. By doing that, Garofalo reveals the shifting understanding of the concepts of crime genre, national, European, and auteur cinema by contextualising the distribution strategies employed for Dogman against the tendencies for the promotion and circulation of Italian and European cinema in the United States. The issue closes with Markus Schleich’s article “Cosmopolitan Crimes: Sebastian Schipper’s Victoria (2015) and the Distribution of European Crime Films” which, alongside questions related to promotion and circulation, analyses the supranational support awarded to the film by Creative Europe Programme (2014–2020) through the Selective Distribution Scheme. Schleich’s work addresses the difficult presence in non-national markets of German films by comparing Victoria to another crime production which travelled well, Run Lola Run.

Overall, the articles in this issue reveal a problematic genrefication of European crime cinema in non-national markets, where the genre belonging is overshadowed by the authorial dimension and the “quality” of the productions. The result is that crime is a genre relying on strong national connotations and, despite its global appeal, struggles to meet an international audience and to manifest an Europeanness of the genre itself.

Acknowledgements

The research presented here has been financed by the research project DETECt — Detecting Transcultural Identity in European Popular Crime Narratives (Horizon 2020, 2018–2021) Grant agreement number 770151.

Data collection and analysis on the circulation of the top-ranked European crime films according to IMDb was performed by Dr Markus Schleich as part of the research carried out within DETECt Work Package 5, “Creative Audiences: Distribution, Accessibility and Meaning-Making of Transcultural European Contents”.

Notes

[1] Data collected in August 2019. It needs to be stressed that IMDb ranking and genre labelling are ever shifting. However, this selection offers an appropriate snapshot of the international popularity of the films. If the film is the result of a co-production agreement, it has been assigned to the country with the majority stake in the production process.

[2] While I am aware of the limits of such benchmarking, considering that the films analysed were distributed in different years, I also think that the data for 2019 nevertheless offers a general idea of where on average a European film finds its audiences. Such a percentage only changed slightly over the years (in 2018 it was a 61%–39% division).

References

1. ’71. Directed by Yann Demange, Film 4/British Film Institute/Screen Yorkshire, 2014.

2. Alaveras, Georgios, Estrella Gomez-Herrera, and Bertin Martens. “Cross-Border Circulation of Films and Cultural Diversity in the EU.” Journal of Cultural Economics, no. 42, 2018, pp.1–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9322-8.

3. Bad Education [La mala educación].Directed byPedro Almodóva/Canal + España/El Deseo, 2004.

4. Baschiera, Stefano. “European Crime Cinema and the Auteur.” European Review, vol. 29, no. 5, 2021, pp. 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798720001143.

5. Baschiera, Stefano, and Francesco Di Chiara. “‘The European Parliament Projecting Cultural Diversity Across Europe’: European Quality Films and the Lux Prize.” Studies in European Cinema, vol. 15, no. 2–3, 2018, pp. 235–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411548.2018.1442619.

6. Baschiera, Stefano, and Markus Schleich, editors. Cultural Mobility through Narrative Media Production in the European Market, June 2021. https://www.detect-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/D4.3-Final.pdf.

7. A Belfast Story. Directed by Nathan Todd, Adnuco Pictures, 2013.

8. Bergfelder, Tim. International Adventures. German Popular Cinema and European Co-productions in the 1960s. Berghahn, 2004.

9. Bondebjerg, Ib, et al. Transnational European Television Drama: Production, Genres and Audiences. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

10. Cold Pursuit. Directed by Hans Petter Moland, Summit Entertainment/Studio Canal/Mas Production, 2019.

11. Crisp, Virginia, and Gabriel Menotti Gonring, editors. Beside the Screen: Moving Images through Distribution, Promotion and Curatio.Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

12. Dogman. Directed by Matteo Garrone, Archimede/Le Pacte/Rai Cinema, 2018.

13. Elsaesser, Thomas. European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam UP, 2004.

14. European Audiovisual Observatory. Yearbook 2018/2019: Key Trends. European Audiovisual Observatory, 2019. https://rm.coe.int/yearbook-keytrends-2018-2019-en/1680938f8e. Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

15. Everybody Knows [Todos lo saben]. Directed by Asghar Farhadi, Memento Films Production/Morena Films/Lucky Red, 2018.

16. Gomorrah [Gomorra]. Directed by Matteo Garrone, Fandango/Rai Cinema, 2008.

17. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo[Män som hatar kvinnor]. Directed by Niels Arden Oplev, Yellow Bird, 2009.

18. Larsonn, Stieg, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Translated by Reg Keeland,Quercus, 2008.

19. Four Against the Bank [Vier gegen die Bank]. Directed byWolfgang Petersen, Hellinger/Doll FIlmproduktion, 2016.

20. Hansen, Kim Toft, Steven Peacock and Sue Turnbull, editors. European TV Crime Drama and Beyond.Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

21. Higson, Andrew. “The Circulation of European Films within Europe.” Comunicazioni Sociali: Journal of Media, Performing Arts and Cultural Studies, no. 3, 2018, pp. 306–23.

22. Iordanova, Dina, and Stuart Cunningham. Digital Disruption: Cinema Moves Online. U of St Andrews P, 2012.

23. Jäckel, Anne. European Film Industries. British Film Institute, 2003.

24. Huw, David Jones. “What Makes European Films Travel?” Conference paper, European Screens, University of York, 5–7 Sept. 2016.

25. Knight, Julia, and Peter Thomas. “Distribution and the Question of Diversity: A Case Study of Cinenova.” Screen, vol.43, no. 9, 2008, pp. 354–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjn040.

26. Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door. Directed by Thomas Jahn, Buena Vista International Film Production/Mr Brown Entertainment, 1997.

27. Layer Cake. Directed by Matthew Vaughn, Marv Film, 2004.

28. Liz, Mariana. Euro-Visions: Europe in Contemporary Cinema. Bloomsbury, 2016.

29. Lobato, Ramon. Shadow Economies of Cinema: Mapping Informal Film Distribution. British Film Institute, 2012.

30. Lobato, Ramon, and Mark David Ryan. “Rethinking Genre Studies Through Distribution Analysis: Issues in International Horror Movie Circuits.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2011.556944.

31. Lock and Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Directed byGuy Ritchie, Handmade Films/Polygram Film Entertainment, 1998.

32. Marhsland [Isla minima]. Directed by Alberto Rodriguez, Atípica Films/Sacromonte Film/Atresmedia Cine, 2014.

33. May God Save Us [Que dios nos perdone]. Directed byRodrigo Sorogoyen, Tornasol Films/ Atresmedia Cine/Hernández y Fernández Producciones Cinematográficas/ Mistery Producciones, 2016.

34. Milla Julio Talavera, et al. Public Financing for Film and Television Content: The State of Soft Money in Europe. European Audiovisual Observatory, July 2016. https://rm.coe.int/public-financing-for-film-and-television-content-the-state-of-soft-mon/16808e46df.

35. Run Lola Run [Lola rennt]. Directed by Tom Tykwer, X-Filme Creative Pool/Arte Deutschland/TVWestdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), 1998.

36. Simone, Patrizia. “The Circulation of European Films in Non-national Markets. Key Figures 2019.” European Audiovisual Observatory, 2021, rm.coe.int/export-2020-en-final-online-version/1680a1e35f.

37. The Sisters Brothers [Les Frères Sisters]. Directed by Jacques Audiard, Why Not Productions, 2018.

38. Shadow Dancer. Directed by James Marsh, BBC Films/Element Pictures/Lipsync Productions, 2012.

39. Szczepanik, Petr, and Patrick Vonderau. Behind the Screen: Inside European Production Cultures. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

40. The Traitor [Il traditore]. Directed by MarcoBellocchio, IBC Movie/Kavac Film/RAI cinema2019.

41. The Truth Commissioner. Directed by Declan Recks, Big Fish Films/Head Gear Films/Kreo Films FZ, 2016.

42. Victoria. Directed by Sebastian Schipper MonkeyBoy/RadicalMedia/The Match Factory, 2015.

43. Volver. Directed by Pedro Almodóvar, El Deseo, 2006.

Suggested Citation

Baschiera, Stefano. “On the Cultural Circulation of Contemporary European Crime Cinema: Editorial.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 22, 2021 pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.22.00

Stefano Baschiera is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Queen’s University Belfast. His work on European cinema and film industries has been published in a variety of edited collections and journals including Film International, Bianco e Nero, Studies in European Cinema and The New Review of Film and Television Studies. He is the co-editor with Russ Hunter of Italian Horror Cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2016) and with Miriam De Rosa of Film and Domestic Space: Architectures, Representations, Dispositif (Edinburgh University Press, 2020).