Decolonial Gesture and the Screening of the Botanical Artist in Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings (Bo Wang and Pan Lu, 2017)

Sarah Cooper

Abstract

Bo Wang and Pan Lu’s split-screen video essay Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings (2017) charts the relationship between its titular categories and British imperialism in China, especially the colonial possession of Hong Kong as a result of the Opium Wars in the nineteenth century. It centres on the collecting of plants from China for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, along with their documentation through botanical drawings by local Chinese artists. The video essay shows fleeting glimpses of several anonymous Chinese paintings, revealing in the process the dual sense of screening at the heart of the colonialist enterprise that involved showcasing the art while obscuring the artist. Wang and Lu, in contrast, return attention to the skills of the Chinese artists. Through their own dual vision, they challenge myriad hierarchical colonial images of human-plant relations. Drawing on Vilém Flusser’s work on the gesture of video and combining this with Walter D. Mignolo’s discussion of decolonial gesture, I show how Wang and Lu question through their own artistic gestures the distortions of the colonial gaze evident within dominant western image regimes. In this, their work speaks indirectly to recent writings in the environmental humanities and critical plant studies that valorise more lateral relations between humans and plants.

Article

Botanical illustration and flower portraiture have long generated images of plants that span a spectrum from the useful to the beautiful. Some of the earliest flower drawings helped people searching for culinary or medicinal plants to find them, while the heyday of flower painting in the Western world in the seventeenth century unleashed unbridled creativity in a grandiose celebration of floral beauty for its own sake (Blunt 1–2). Combining use value and beauty, the botanical art that emerged with the rise of scientific botany and in tandem with modern botanical nomenclature in the eighteenth century was rigorous in its naturalistic representation. In a tradition that survives through to today, the artist would work closely with botanists, if they were not such a plant expert themselves, learning what to focus on and how to dissect specimens in order to portray the plant’s specific characteristics with precision. Empirical observation and accuracy in the rendering of colour, form, texture, and scale are at the heart of this art form which works in the service of science while never diminishing the aesthetic appeal of the finished work to the untrained non-scientific eye. The history of botanical art is, however, far from innocuous and is, in fact, inseparable from a colonial past. It is one such imperialist facet of botanic history that Bo Wang and Pan Lu explore in their video essay, Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings (2017), which will be the focus of my discussion in this article.[1]

This split-screen work charts the relationship between its titular categories and British imperialism in China, especially the taking possession of Hong Kong as a result of the Opium Wars in the nineteenth century. It centres on the collection of plants from China for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew—a mission that was at the heart of the imperialist project—along with their documentation through botanical paintings by local Chinese artists, and the theory of miasma used to justify colonial hierarchies. This theory was founded on a belief that a noxious miasma arose when the air stagnated, emanating from the soil, as well as from human and animal bodies. In Hong Kong, the Europeans, particularly the British, felt that the higher up they were, the better the air quality would be, instilling a vertical hierarchy based on racial and social status. Wang and Lu’s video essay questions this and other aspects of colonial hierarchical stratification through attention to plant collection and its associated image regimes.

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings intersperses extracts of Hollywood feature films and a film from the Pathé archives about Kew Gardens with paintings by Chinese artists (botanical and general), archival photographs of Hong Kong, and other footage filmed by Wang. Highlighting botanical paintings by Chinese artists, alongside other export paintings, the video essay reveals the dual sense of screening at the heart of the colonialist enterprise, as it pertained to plant collection, which involved circulating the botanical art while obscuring the artist.[2] Wang and Lu, in contrast, return attention to the skill of the Chinese artists through their own artistic gestures. Drawing on Vilém Flusser’s work on the gesture of video and combining this with Walter D. Mignolo’s discussion of decolonial gesture, I show how Wang and Lu highlight the work of the Chinese artists by questioning the distortions of the colonial gaze evident within dominant Western image regimes. Mignolo defines decolonial gestures (fictional and non-fictional, artistic and non-artistic) as those that confront the colonial matrix, pointing to the task that colonial subjects are undertaking all over the world: “to engage in world-making not regulated by the colonial matrix” (“Looking”).[3] Through the form of the video essay, Wang and Lu challenge the regulations of the colonial matrix of power by means of their critical engagement with the circulation of plants and botanical art.Through their practice as video artists, and by valorising the skills of the Chinese artists whom Western history has side-lined, Wang and Lu open up a space in which to challenge the hierarchical relationship between humans and plants in and beyond the Western world. In this, they join tacitly with other moves within the environmental humanities that explore more horizontal connections with the vegetal world. The Chinese botanical artists whose work Wang and Lu attend to are inextricably linked with Kew Gardens. Showing how their painting is entwined with the history of plant collection for Kew and its ensuing image repertoire, along with broader colonial image regimes, will lead to seeing how the Chinese artists, along with Wang and Lu, gesture beyond colonial vision.

Kew Gardens and the (Chinese) Botanical Artist

The botanic garden in the south-west of London at Kew was established in 1759 by Princess Augusta, with the aid of Lord Bute, after the death of her husband. There was a strong desire from the outset for the garden to become the hub of botanical exchange between the colonies. Plants and seeds were brought to Britain via colonial routes, and plants “introduced” to the British Isles were taken from their native habitats around the world. The publication of the first catalogue of the gardens in 1768, titled Hortus Kewensis, showed that by the late eighteenth century Kew was already becoming one of the most extensive repositories for the world’s flora (Desmond 43). The garden was created initially as a royal private space and when Augusta died, George III inherited the estate and united it with the royal estate in Richmond, which led to the plural use of gardens known today (Parker and Ross-Jones 8). Joseph Banks, a wealthy landowner who was also a passionate naturalist and who accompanied James Cook on his first voyage around the world, worked with George III to establish the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. That Kew can announce in promotional films today that it is “the most biodiverse spot in the world”, on the basis of the plants that it grows there and at its sister site Wakehurst, owes a great deal to the colonial history of how the plants were first brought together in previous centuries (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kev, “World-Class Plants”). Botanical artists have played a key role in recording and preserving the history of plants collected over the years.

Botanical art was integral to the scientific operations at Kew from the very beginning. The first resident botanical artist was Austrian botanical illustrator Franz Andreas Bauer, appointed by Banks in 1790 (Flower 317). He recorded plants as they arrived from Africa, Asia, and the Americas following the newly adopted Linnaean binomial system of plant classification, which identified them according to their sexual characteristics. He pioneered the use of a microscope to scrutinise minute details. The importance of botanical artists’ painting and drawing has not changed over the years in spite of developments in imaging technologies.[4] In A Prospect of Kew (1981), part of the BBC2 television documentary series on natural history The World About Us, nature writer and narrator Richard Mabey declares, over images of a plant being painted for Curtis’s botanical magazine, that paintings are regarded as more helpful than photographs in capturing a plant’s identifying characteristics. This is still the case over forty years later.[5] Historically, botanical line drawings and paintings were not only executed after the collected plants arrived at Kew but were commissioned in the field prior to their being shipped to the British Isles. Botanical art was embedded thus at the start of the plant collecting process, and this is demonstrated through one such commissioning of botanical paintings from local Chinese artists two hundred years ago.

It was at the behest of Joseph Banks in the early nineteenth century that John Reeves, tea officer to the East India Company, was invited to collect plants from China. As Reeves scholar Kate Bailey notes, Reeves collected and researched a wide range of material for Banks, sending back to England frequent shipments of plants. Reeves’ work collecting, describing, and classifying botanical material led to his becoming a corresponding member of the Horticultural Society, which also involved commissioning drawings (Bailey, Reeves 66). Reeves would have employed many different local Canton artists to paint for him (108).[6] The names of four Chinese painters are recorded in Reeves’ handwritten books between 1828–1830—Asung, Akam, Akew, and Akut—along with a list of drawings made and details of remuneration in dollars (108).[7] What is now the Reeves Collection of Chinese Botanical Drawings held at the Royal Horticultural Society’s Lindley Library in London is part of the illustrated record of his extensive plant collecting in China, alongside holdings in archives at Kew Gardens and the Natural History Museum in London. As Bailey observes, there are many different kinds of botanical illustrations, and the first of these is applied art akin to technical drawing in which accuracy is key since the images help to identify plant specimens. They are meant to convey knowledge and are frequently accompanied by text. The images of the Reeves Collection by the Chinese artists, in contrast, were detailed plant portraits, scrupulously accurate but unaccompanied by text. The aim was to show the plant as it was growing in China. Chinese botanical illustrators would sometimes create a composite image showing buds, inflorescence, and seed heads, even though these were out of keeping with the plant as it would appear in one season (15–17). As Wang and Lu’s video essay reveals in a sequence that begins with a mid-twentieth century promotional film about Kew, Reeves would ensure that the work by the Chinese artists would circulate alongside the collected plants, uniting them in the imperialist mission.

Having focused on Reeves’ arrival in China from the outset of Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings, counterposing Chinese export paintings on the left-hand side of the screen with contemporary video footage of tourists photographing themselves on the deck of boats cruising a city harbour on the right, Wang then turns explicitly to Reeves’ plant collecting for Kew in his voiceover commentary. An extract from a 1962 film titled Kew Gardens plays on the left-hand side of the screen as the right-hand side remains black (Fig. 1).[8]

Figure 1: An extract from Kew Gardens (1962).

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings (Bo Wang and Pan Lu, 2017). Screenshot.

Wang speaks over the Kew Gardens commentary intermittently, noting first that thanks to Banks, Kew had developed a network of gardeners, plant hunters, and naturalists who transported plants from colonies all over the world. In its entirety, Kew Gardens is a short film from the Pathé archives that runs for just over two minutes. In Wang and Lu’s video essay this is edited to just over one minute to feature the beginning and the end. Kew Gardens is concerned with showcasing the geographical diversity of the gardens’ plant life and to map this onto people. In this, it picks up a strand of representation of Kew that dates back to a longer film made during the Second World War, World Garden (1942), whichwas directed by documentary filmmaker Robin Carruthers, who would go on most notably to make the Oscar-nominated colonial film They Planted a Stone (1953) on the British presence in Sudan.

Actor Charles Lefeaux provides the commentary in this earlier short, explaining at the start over an aerial panning shot of the gardens and the rooftops of London that Kew is a world garden because it has “flowers and shrubs and trees from every country in the world.” In both Kew films, the garden is constructed as an ideal space, suggesting continuity in the twentieth century with what historian of science Jim Endersby notes of the Edenic plan of the early modern garden to bring everything in the world back together. World Garden, like the later Kew Gardens, thereby posits an ideological vision that disguises the power relations behind its construction as idyll. Although the world is at war in the earlier film, there is no sign of it in the blue skies and verdant sunlit gardens, and although the accumulation of various plants and people in London in the later film is presented equally sunnily, the riven colonial backdrop is still there in multi-cultural 1960s Britain. The aspiration of bringing together myriad aspects of the globe in one place is driven by an unacknowledged imperialism and ethnocentrism, led here by plants. Senior figures at Kew Gardens have sought recently to address the connection between Kew and colonialism as part of a widely reported pledge to decolonise Kew, committing not only to equality, diversity, and inclusion principles in the present and future but also to revisiting its history (Antonelli and Deverell). Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings precedes this ambition, already initiating critical processes that challenge the colonial matrix in its own artistic context. The positioning of the extract from Kew Gardens in this video essay is crucial to exposing the colonial mission that guided the botanical paintings Reeves commissioned from the local Chinese artists.

The male voiceover of the Kew Gardens extract declares over percussive music how beautiful the Orient is, exclaiming “what a pity it is that the Far East with its exotic flowers, its carved temples, is so very far away.”[9] Querying the initial location, the voiceover continues to observe that we are not in the Far East but in tropical Africa, as a black gardener is shown tending to a hibiscus plant and a close-up of one of its red blooms is shown “that only grows near equatorial ponds and swamps.” As Wang and Lu’s edit then takes us to the closing part of the film, Wang describes how imperial expansions remapped the order of society and the transfer of plants rearranged the order of nature. The impetus behind the earlier film, World Garden, to set up Kew as a microcosm of the world, is returned to in the final sentence of the Kew Gardens extract as the camera pans to a red double-decker bus pulling up outside the place that presents “the whole of this colourful world of ours in miniature. And to get there, you take a bus.” This London garden is, then, still a world garden in the sense that plants are gathered together from around the world. Yet the colonising as well as Orientalising principles that inform the declared ease of access to this world by bus are made more rather than less apparent by focusing on people of colour tending to or visiting the garden, who are set up on the side of the exotic through their opening alignment with flowers. Through their editing and commentary, however, Wang and Lu succeed in challenging the harmony of the narrative of how diverse people and flowers grow side-by-side at Kew, and this carries over to their treatment of Reeves’ commissioned Chinese botanical art before it spans the whole essay.

The positioning of the edited Kew Gardens film within the colonial historical context of Reeves’ plant collecting for Banks and Kew jars with its harmonious presentation of content. Wang and Lu bring out the imperialist structures that enable the earlier film’s celebration of global diversity at the heart of London and the fault lines within its seamless vision that register the dissonance of colonialism instead. In Wang and Lu’s video essay, the ensuing sequence displaces Kew Gardens with close-ups of plants in a darkened space, lit by colourful lights and accompanied by synthetic music.[10] These images that play on the right are then joined by botanical art on the left, as Wang’s commentary specifies that few specimens could survive the four-month long journey from Canton to England. Hence the importance of local artists’ paintings, which back in London occasioned such a rapturous visual experience that they made horticulture and botany a new fashion for the upper classes.

Figures 2–8: Botanical paintings/plants from botanic gardens.

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshots.

The paintings of the talented botanical artists that Wang and Lu show on screen are not attached to an image of the artist. This contrasts with the present-day film images of Chinese painters in brightly lit studios copying European paintings, or reproducing them through printers, which appear earlier on. Although there are records of the names of the artists in Reeves’ personal papers, there was no cult of the artist when his commissioned drawings were circulated back in Britain, such that individual painters went unrecognised and remained invisible. Wang’s dynamic camera peruses the images in close-up, not giving us a holistic view of any one of the painted plants, but panning up, down, and sideways around segments of the plant paintings in all their brightness, as a camera also tracks the contrasting darkly lit living plants on the other screen. Listening to the commentary about the European fascination with this artwork over mobile camera images of botanical paintings, shadowed by the eerie music as well as the blend of darkness and coloured lighting of the plants filmed on the other screen, produces a discordant effect. The camera movements stand in for those of the viewer’s eyes that would otherwise choose where and how to look at these paintings, and the body and brushstrokes of the artist are displaced by a broad-brush filmic approach to living and painted plants. Looking thus at a painted representation of the Prunus cv. hybrid tree (Fig. 7) or a Traveller’s palm, Urania speciosa (Fig. 8),both part of the Reeves Collection, is not just a matter of admiring the beauty of the paintings or seeing their usefulness in botanical terms.[11] It is, rather, to be prompted to think again about the context of their production from which they went into circulation far from the roots of the plant that inspired it. In their filming of the botanical art and their juxtaposition of it with living plants, Wang and Lu re-view the artistic gesture of painting through video and thereby begin to unmake the Western view of the world.

Decolonising Artistic Gesture

Media theorist Vilém Flusser characterises gesture as a movement of the body or of a tool connected to it, for which there is no satisfactory causal explanation (3). For Flusser, gestures, whether tied to technology or not, reveal a way of being-in-the-world. Writing about the gesture of painting, and true to a desire to actually see the gesture rather than the bodies that move in it and the objects it might be trying to portray, Flusser notes:

“the world” is not an objective context of “objects” but a context of interacting concrete events, some of which have meaning inasmuch as they give it. If, by observing such a gesture as that of painting, one can get free of the objective worldview of the West, one can see how “having meaning,” “giving meaning,” “changing the world,” and “being there for others” are four formulations expressing the same state of affairs. (70)

When Flusser turns to the gesture of filming, he considers it from the perspective of a viewer rather than a filmmaker. He defines the filmic gesture as follows: “it works with scissors and glue on strips that contain the traces of scenes so as to produce a strip that represents history, that is, historical time, in cavelike basilicas. […] Accordingly, we need to direct our attention to this gesture rather than to the manipulation of the film camera” (88). Wang and Lu’s work is on video rather than a filmstrip, however, and this distinguishes it in a number of ways, even as the aforementioned gestures of painting and film editing borrowed from these other media are an important aspect of the completed essay. Defining videotape as a “dialogical memory,” Flusser notes that film and video belong to different image genealogies: “Genealogically, film can be traced to the line fresco–painting–photography; video can be traced back to the line water surface–magnifying glass–microscope–telescope. In its origin, film is an artistic tool: it depicts; video, conversely, is an epistemological tool: it presents, speculates, and philosophizes” (144). For Flusser, video falls into the category of posthistorical gesture insofar as it composes alternative events (posthistorical engagement) rather than aiming only to commemorate events (historical engagement) (145). Most pertinently for my analysis of Wang and Lu’s work, Flusser notes how video can be manipulated with gestures borrowed from other media, specifying nonetheless that they will have a new quality: “This new quality will come from the dialogic structure of video. To put it briefly, we will be dealing with a gesture that no longer attempts to produce a work whose subject is the maker but rather with one that the gesture of video attempts instead to produce an event in which the maker participates, even if he is controlling it” (145–6). In Wang and Lu’s work, the editing on each side of the screen and the relation between them that is left to the viewer to navigate is a filmic gesture that is formally akin to the one Flusser describes in medium specific terms. However, when manipulated through video in combination with the mobile camera’s re-viewing of paintings, Wang and Lu’s artistic gestures participate in a renegotiation of a relation to the world different from the objective worldview of the West.

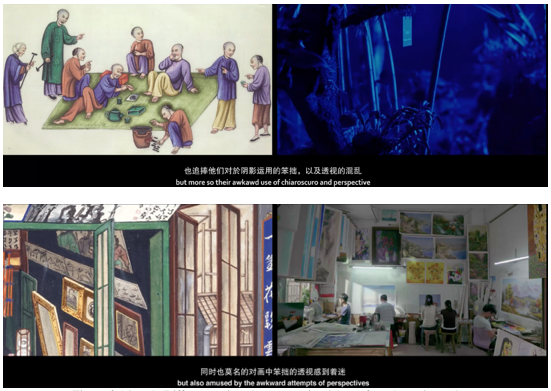

Inserted after the botanical art is a succession of other paintings of Chinese settings, over which Wang explains the European fascination with their meticulousness, bold use of colour, and deft brushwork, but more so their awkward use of chiaroscuro and perspective. The final painting in this sequence (Fig. 9) shows how the people in the frame who are further away from the painter’s position do not recede into the distance but seem to sit at the same size at a higher level, echoing earlier points about perspective (Fig.10).

Figure 9 (above): Different painterly perspectives/plants from botanic gardens.

Figure 10 (below): Different painterly perspectives/a modern-day artist studio.

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshots.

As Wang will observe in the closing moments of the video essay, it was not the case that Chinese artists had no idea of perspective, contrary to the way in which Westerners would belittle their talent in this regard. As Kate Bailey also suggests in her scholarship on Reeves and the Chinese drawings, the idea of perspective was just different and this was partly due to the influence of the vertical scroll format: “on which distant objects such as the sky and mountain ranges would be painted at the top and closer features, images of people and pavilions, for example, appeared towards the bottom” (Reeves 22).Commenting further on the botanical art of the Reeves Collection, she notes that Western painters would paint what they thought they saw, foreshortening leaves and flower parts pointed towards the viewer. In contrast, the traditional Chinese painters would have painted the petals and leaves as they knew them to be, resulting in the fact that in the Reeves Collection, petals, sepals, leaves, and stems were not foreshortened (22). Wang and Lu’s focus on the work of Chinese artists throughout their essay reveals a challenge to, rather than ignorance of, Western perspective. In this, the original Chinese artists were already performing decolonial gestures, as Mignolo defines them, which are enhanced by Wang and Lu in their treatment of painting, as well as film and photography.

Through their own use of perspective, Chinese artists were asserting their break from the aesthetic vision of Renaissance perspective and “delinking” from the imperialists in a manner Mignolo describes as

always already being engaged in project [sic] and processes of re-existence, re-surgence and re-emergence of all signs of living in plenitude and harmony that coloniality repressed, suppressed, or disavowed in the name and justification of “modernity” as salvation. (“Looking”)

In not replicating Renaissance perspective, the artists were going against the Western system while working for it, perpetuating a way of seeing that does not conform to Western expectations and that dissociates from what the imperialist gaze deems to be correct. Asserting a way of seeing through the gestures of botanical art that Westerners derided in perspectival terms, even as the art galvanised an entire generation of horticultural passion, is already a gesture critical of the colonial matrix, which Wang and Lu take up in their own artistic gestures.

From the content of the images, through the editing that disturbs the colonial narrative, to the split-screen vision that challenges one perspectival viewpoint, Wang and Lu’s editing gives the body of the video essay a movement akin to that which Mignolo describes. Mignolo writes: “it is a body movement which carries a decolonial sentiment or/and a decolonial intention; a movement that points toward something in relation to something already constituted that the addressed of the gesture or whomever sees the gesture, recognizes in relation to ‘colonial gesture’” (“Looking”). Colonial gestures are embedded in the different films that their essay cites and engages with critically, while also being at work tacitly in the botanical paintings through the commissioning process and context of circulation, as Reeves supervised their execution while never eradicating their perspectival difference. The export of the Chinese botanical artists’ paintings became part of the colonial traffic in images to which Wang and Lu’s video essay refers, the legacy of which travels through to more recent moving images. In addition to Kew Gardens which not only testifies to the transfer of plants from Asia and other parts of the world to London, but which is a latter-day part of the colonial botanical image culture that perpetuates an ideological vision, Hollywood films also feature in extract form, edited in such a way as to propagate Wang and Lu’s own decolonial artistic gestures across the entire video essay.

With Wang’s voiceover regarding Western perceptions of the awkward perspective of the Chinese paintings still resonating, an orchestral score becomes audible as an extract from Tai Pan (Daryl Duke, 1986) appears on the right-hand side of the screen. It shows the European artist Aristotle Quance (Norman Rodway) painting a nude Asian female model at his easel before he gets distracted by external events.

Figure 11: An extract from Tai Pan (Daryl Duke, 1986). Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

The sequence from Duke’s film unfolds to show the claiming of Hong Kong, declaring its soil to be British soil. The implications of this possession of soil manifest themselves not only in terms of the export of plants and paintings. Wang recounts later in Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings over photographic images of the plants in the Hong Kong botanical garden, that when this garden opened to the public, only the European public were allowed in. These colonial gardens that relate back to the Kew hub expand the colonial mission that took plants from their natural habitat while restricting local Chinese from having access to that habitat. The image of a European artist and his Asian model that opens the clip from Tai Pan is however also a reminder of the underpinning racial and sexual hierarchies of such possession of plants and soil through the Western (painterly) objectification and treatment of people, especially Asian women.

Such European, especially British, belief in their superiority is referred to over a shot of a bust of the eighteenth-century Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. The commentary reminds viewers that in 1735 his Systema Naturae placed humans inside the natural world’s classification for the first time, dividing the human species problematically into creative white Europeans; lazy black Africanus; undisciplined red Americans; and melancholic yellow Asiaticus. Wang and Lu invoke distancing techniques to query any alignment with Linnaeus, showing first a close-up of his bust, followed by a more distant shot and then a shot in which the Asian camera operators are shown filming the statue before walking away and leaving it, along with their equipment.

Figure 12: Taking distance from Linnaeus/an extract from Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (Henry King, 1955). Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

The ostensibly seamless alignment of people and plants that featured in the Kew Gardens film extract is further undercut through this more distanced relation to Linnaeus’s racist classification of humans within his botanical treatise. This undercutting aligns too with Wang and Lu’s treatment of Hollywood film. The decolonial artistic gesture here is one of exposing, through the continued precision of attention to editing, hierarchically aligned relations between humans and plants, which have always benefited the colonisers. The European artist who is pictured painting the Asian model in Tai Pan shifts focus from the painting of flowers to the painting of women, cementing nonetheless the continuity of a possessive hierarchy in the process.

Extracts from Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (Henry King, 1955) feature in the video essay, demonstrating Wang’s commentary on the fact that territorial colonial expansion was facilitated by advances in plant transportation methods—most significantly, Wardian cases—and involved sending more seeds, plant samples, and drawings to Britain, as more people were also sent to the colonies.[12] One extract from Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing appears on both sides of the screen, as Dr Han Suyin (Jennifer Jones) declares herself to feel like a seed, sprouting up, clutching at life, hearing and smelling the sun, with a heightened awareness of surfaces and textures (Fig. 13). As the scene progresses, the left-hand side of the screen splits again to show Mark Elliott’s (William Holden) glistening forehead, emphasising the studio construction of the humid atmosphere (Wang notes in voiceover that this filming took place in California and not Hong Kong). Towards the end of the video essay, a final extract shows the couple at a hilltop meeting place, with the left-hand screen fixed steadfastly on a black-and-white archival photograph emphasising Hong Kong’s verticality. Dr Han is pictured finally standing by a tree, her apricot dress moving in the breeze as she waves (Fig. 14).

Figure 13: Dr Han Suyin (Jennifer Jones) and Mark Elliott (William Holden) in Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

Figure 14: An archive photograph of Hong Kong/Dr Han Suyin in Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

The shot is an instantiation of her privileged yet fragile floral status in a racialised and sexualised colonial hierarchy reinforced by Hong Kong’s social stratification exemplified in the earlier extract (Fig. 15–16).

Figure 15 (above): Dr Han Suyin and Mark Elliott in Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Figure 16 (below): Dr Han Suyin and Mark Elliott/a Chinese funeral procession in Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshots.

The association that Dr Han makes between herself and a plant is echoed implicitly through Wang and Lu’s earlier inclusion of an extract from Broken Blossoms (D. W. Griffith, 1919). This film extract points to the kind of trading activity that Reeves would have been part of in his own era.

Figure 17: A Chinese painting of trade/an extract from D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919).

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

Significantly, though, this is a film in which Lilian Gish plays a young girl nicknamed “White Blossom” by the Chinese man, blending both skin colour and beauty in the connection between flowers and the feminine. The fair-skinned-woman-plant left standing on the hilltop alongside a tree in the final extract from Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing co-opts the natural metaphor in the service of the hierarchically oriented, colonialist ideology operative in Hong Kong. From the painting of an Asian nude by a European artist, through images of a fair-skinned woman comparing herself to a plant, to a film in which flowers, femininity, and whiteness are entwined, Hollywood perpetuates the colonial relations between people and plants witnessed throughout Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings, which Wang and Lu underscore and trouble from beginning to end.

In the video essay’s concluding moments, Wang’s commentary emphasises that Reeves, among other imperialists, overlooked what was there whenever they defined what could be seen.

Figures 18–19: Questioning the eyes of Empire/plants from botanic gardens.

Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Screenshot.

It is for this reason that viewers of Wang and Lu’s work are encouraged to look again at relations between plants and people from the different perspective of the Chinese artists as seen through the lens of this video essay. Noting that these artists were far more advanced than Westerners gave them credit for at the time, Wang and Lu position the painters’ different approach to painting as part of a broader decolonial gesture that they extend and develop in their own artistic medium. The Western perspective of the selection of film extracts included in their work involves comparing people to plants, or women to flowers, and objectifying or possessing them accordingly. Through their work on the colonial transfer of plants, Wang and Lu show how analogical thinking of the kind that compares humans and plants can perpetuate rather than dispel hierarchies when mobilised by dominant ideologies. Their critique of this regime of representation does not, however, render human relations with plants irredeemably problematic. In this, Wang and Lu’s work speaks indirectly to indigenous teachings from different parts of the world, along with philosophical exploration of plants as persons, which seek kinship with plant life in more lateral terms (Hall; Kimmerer). It also dovetails with a broader tendency in the field of critical plant studies to attend centrally to the vegetal realm rather than leaving it at the margins of consideration (Marder). It is the work of Anna Tsing here, though, that offers the most fitting comparison.

In her research on the matsutake mushroom Tsing talks of the importance of arts of noticing, noting that although not very popular these days, taxonomy draws attention to the pleasure of naming through which we notice the diversity of life. She adds that collecting went together with painting, also an art of noticing (6). While Tsing is alert to the colonial regimes with which such noticing is entangled, there is also a sense in which the painterly skill of noticing might not always play into the hands of the colonialists. It could indeed be classified instead as what she terms an art of inclusion, closer to what enables us to preserve rather than callously disregard what we see around us, leading to a kind of multi-species love. In their own medium and art of noticing, Wang and Lu’s video essaystrives towards lateral plant–human relations through its exposition and critique of colonial hierarchies, drawing attention to what the imperialists missed when they looked at both the culture and the paintings of the life—that of plants and humans—that they appropriated. Indebted to the different perspective proffered by the Chinese painters through their vision and gestures, Wang and Lu disrupt the history of oppressive colonial analogical thinking, encouraging their viewers, too, to explore more ethical relations with (images of) plants.

Notes

[1] I thank Bo Wang for sharing a copy of this video essay with me and for corresponding with me about its production. Wang and Lu wrote the script, and Wang was responsible for camera, editing, and voiceover. The video essay is also a two-channel video installation. For more information about screenings and exhibitions, see Bo Wang’s website (“Miasma”).

[2] The term “Chinese export painting” was coined by Western art historians in order to distinguish this kind of painting from traditional Chinese painting. Such works were made for export to the West.

[3] Mignolo’s polemical project strives to move beyond post-coloniality, deeming this a Euro-centered project through the poststructuralist theory that grounds the postcolonial canon. In his view, decoloniality is more open than is the postcolonial to other sources of critique and activism that are associated with figures from Latin America, Asia, and Africa, for example Cabral, Ghandhi, and Fanon. While this latter point is open to question, given that postcolonial theoretical discussion does not occlude these figures, my interest lies in Mignolo’s concept of gesture and how it challenges the colonial project. See also his article “DELINKING: The Rhetoric of Modernity, The Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of Decoloniality”.

[4] Such developments in imaging technologies have been abundant over the last three centuries. Karl Blossfeldt’s plant photography provided an alternative view to painted and drawn plants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Flower 273). Leendert Blok’s colour photographic work is pertinent too, since by the 1920s the colour quality of prints began to satisfy naturalists and botanists in a way that it never did before (33). Other more recent imaging techniques render visible the insides and outsides of flowers as well as what the naked eye cannot see. See, for example, the use of 3D technologies by Japanese artist Macoto Murayama (35), and of ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence in the work of American photographer Craig P. Burrows (153).

[5] See, for example, Kew’s promotional and informational films, “What is Botanical Art?”and “How to Paint Like a Botanical Artist”.

[6] The Reeves Collection at the RHS Lindley Library was the subject of a conservation research project in the early 2000s (Bailey, “Reeves Collection”).

[7] Bailey notes that there could have been a fifth painter too.

[8] Extracts from Kew Gardens also feature in Wang and Lu’s essay film Many Undulating Things (2019), centred likewise on Hong Kong.

[9] This is not the only film about Kew Gardens made between the 1940s and the 1960s to look to the East or to mention Orientalist stereotypes. See, for example, Trees (1940) and Kew Blossoms (1967).

[10] These plants were filmed in a botanic garden in Shenzhen, which borders Hong Kong. I thank Bo Wang for this production information.

[11] Figures 2–8 include images from beyond the Reeves Collection as Wang films botanical postcards drawn from London’s Natural History Museum Library.

[12] These extracts from King’s film, along with commentary on Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s cases, recur in Many Undulating Things.

References

1. Antonelli, Alexandre. “The Time Has Come to Decolonise Botanical Gardens like Kew.” The Independent, 26 June 2020, www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/kew-gardens-black-lives-matter-decolonise-botanical-a9585661.html.

2. Bailey, Kate. John Reeves: Pioneering Collector of Chinese Plants and Botanical Art. ACC Art Books, 2019.

3. ---. “The Reeves Collection of Chinese Botanical Drawings.” The Plantsman, Dec. 2010, pp. 218–25.

4. Blossom Time Aka Saving the Fruit or Kew Gardens at Springtime. British Pathé, 1963, www.britishpathe.com/video/blossom-time-aka-saving-the-fruit-or-kew-gardens/query/blossom+time.

5. Blunt, Wilfrid. The Art of Botanical Illustration: An Illustrated History. 1950. 4th ed., Dover Publications, 1994.

Carruthers,Robin, director. They Planted a Stone. World Wide Pictures, 1953.6. ---. director. World Garden. Spectator,1942.

7. Desmond, Ray. Kew: The History of the Royal Botanic Gardens. The Harvill Press, 1995.

8. Deverell, Richard. “Addressing Racism Past and Present.” Kew Royal Botanical Gardens, 12 June 2020, www.kew.org/read-and-watch/kew-addresses-racism.

9. Duke,Daryl, director. Tai Pan. De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, 1986.

10. Endersby, Jim. “Gardens of Empire: The Role of Kew and Colonial Botanic Gardens.” Gresham College, 2 Dec. 2019, www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/gardens-of-empire.

11. Flower: Exploring the World in Bloom. Curated by Phaidon Editors, Phaidon, 2020.

12. Flusser, Vilém. Gestures. 1999.Translated by Nancy Ann Roth, U of Minnesota P, 2014. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001.

13. Griffith, D. W, director. Broken Blossoms. D. W. Griffith Productions, 1919.

14. Hall, Matthew. Plants as Persons: A Philosophical Botany. SUNY, 2011.

15. Kew Blossoms. British Pathé, 1967, www.britishpathe.com/video/kew-blossoms/query/kew+blossoms.

16. Kew Gardens.British Pathé,1962, www.britishpathe.com/video/kew-gardens.

17. Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions, 2013.

18. King, Henry. Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing. Twentieth Century Fox, 1955.

19. Lu, Pan, and Bo Wang, Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings.Andrew Lone, 2017.

20. ---, directors. Many Undulating Things.BÖC Features Production and Ulsan MBC Co-production, 2019.

21. Marder, Michael. Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. Columbia UP, 2013.

22. “Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings.” Bo-wang.net, www.bo-wang.net/miasma.html. Accessed 30 May 2022.

23. Mignolo, Walter D. “DELINKING: The Rhetoric of Modernity, The Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of Decoloniality.” Cultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 2–3, 2007, pp. 449–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647.

24. ---. “Looking for the Meaning of Decolonial Gesture.” Hemispheric Institute, vol. 11, no. 1, 2014, edited by Jill Lane, Marcial Godoy-Anativia and Macarena Gómez Barris, hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-11-1-decolonial-gesture/11-1-essays/looking-for-the-meaning-of-decolonial-gesture.html.

25. Parker, Lynn, and Kiri Ross-Jones. The Story of Kew Gardens in Photographs.Arcturus Publishing Limited, 2013.

26. A Prospect of Kew. World About Us Series, BBC2, 1981.

27. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.“The World-Class Plants at Kew.” YouTube, 1 Apr. 2020, youtu.be/QVCM2lVgbg4.

28. ---. “How to Paint Like a Botanical Artist.” 29 Apr.2021, youtu.be/3No8SaxkxL8.

29. ---. “What is Botanical Art?”YouTube, 25 Apr. 2019, youtu.be/_B6yRDDxOzw.

30. Trees.British Pathé,1940, www.britishpathe.com/video/trees/query/trees.

31. Tsing, Anna. “Arts of Inclusion, or, How to Love a Mushroom.” Australian Humanities Review, no. 50, 2011, pp. 5–21. https://doi.org/10.22459/AHR.50.2011.01.

Suggested Citation

Cooper, Sarah. “Decolonial Gesture and the Screening of the Botanical Artist in Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings (Bo Wang and Pan Lu, 2017).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 23, 2022, pp. 93–110. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.23.05

Sarah Cooper is Professor of Film Studies at King’s College London. Her recent publications include Film and the Imagined Image (Edinburgh University Press, 2019) and an edited volume of Paragraph: A Journal of Modern Critical Theory, “New Takes on Film and Imagination” (vol. 43, no. 3, 2020). She has written previously on plants and film, attending specifically to flowers in articles on Rose Lowder, Jessica Hausner, and F. Percy Smith.