Recognising and Addressing Unconscious Bias and Structural Inequalities: A Case Study Within Television Idea Development

Lucy Brown, Rosamund Davies and Funke Oyebanjo

[PDF]

Abstract

This article examines the idea development process within the UK television industry and raises the question of who has power and agency within it. Recently, there has been much discussion within the television industry about the commercial and social imperative for greater diversity, inclusion and risk taking in programme making, in order to both represent and appeal to contemporary audiences. However, our research suggests that there is at the same time a sense of disempowerment, a feeling that television culture itself is inhibiting this change and that individuals can do little to influence it. Building on existing research in the creative industries, this case study draws on observations, interviews and surveys carried out within the context of a talent development scheme and wider consultation with television development professionals. We will discuss the reasons for these contradictory currents of feeling, including the ways in which unconscious bias may operate to perpetuate inequalities and exclusions. Our article proposes that recognising and addressing unconscious bias within the idea development process is an important element in the wider process of tackling structural inequality in the television industry through collective action and institutional change.

Article

Figure 1: Abstract image representing the tangle of assumptions, contingencies and confusions that can occur in television idea development. Generated by Rosamund Davies, using DALL·E.

In this article we present a qualitative case study, based in the United Kingdom, in which we describe and interpret the ways that new entrants to the UK television industry responded to their encounter with television industry processes and cultures, as part of a talent scheme that introduced participants to the process of idea development in factual entertainment. The aim of the study was to investigate how diversity (i.e., with regard to race, gender, cultural background, etc. of individuals involved) might affect the range and originality of ideas developed within the scheme. Our research suggests that, while diversity of participants can positively affect the range and originality of ideas, the mutual reinforcement of unconscious bias and structural inequalities can also prevent such ideas emerging.

Background

The United Kingdom is a culturally diverse society. It has a long history of immigration, including from its former colonies in Africa and Asia, as well as more recently from the European Union, from which there was free movement of people into the UK, until the United Kingdom officially left the Union in January 2021. The most recent statistics provided by the UK government, taken from the 2011 census, suggest that 13% of the population identify as Black, Asian or belonging to a “Mixed” or “Other” ethnic group and 13% of the UK population were born in another country (“Population”). Although the UK has a legal framework that aims to prevent negative discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and other characteristics such as disability and sexuality (Equality Act 2010), research continues to suggest that discrimination and disadvantage persist with regard to these characteristics (Hackett et al.; Siddique; Zwysen et al.), as well as in relation to class (Friedman and Laurison), which is not a characteristic currently protected under the Equality Act. One area of disadvantage is through underrepresentation in high-paying and high-status jobs, including the television sector (Friedman and Laurison; Diversity). The latter is a mature sector, which includes Public Service Broadcasters (PSB), e.g., BBC, ITV, Channel 4, as well as many non-publicly funded channels, both small operators and large companies (e.g., Sky). Services comprise broadcast, cable, satellite channels, free-to-air, free-to-view and pay TV, scheduled and on-demand programming.

Following deregulation in the 1990s, which required the BBC to commission at least 25% of its output from independent production companies (Broadcasting Act 1990), the sector also comprises a large number of independent production and post-production companies, which supply the channels with content. Independent production has seen extensive consolidation in the last twenty years and is dominated by so called super-indies that have a global reach (Chalaby). Meanwhile, the BBC and ITV production subsidiaries, BBC Studios and ITV studios, also produce content for other channels. This complex network of ownership, commissioning and production chains has recently been impacted by the rise of streaming platforms offering television programming to global audiences, increasing competition over both content and audiences (“Biggest Challenges”). The television sector is regulated by the UK’s communications regulator, the Office of Communications (commonly known as Ofcom).[1] In 2019, Ofcom reported that both women and people from minority ethnic backgrounds were underrepresented in senior management roles in the UK television industry, with people from a minority ethnic background also underrepresented in creative and content production roles. Meanwhile, people with a disability and people from a working-class background were underrepresented across the industry as a whole, compared to the UK labour market population (4–30).

There has been much discussion, within both the television industry and the academy, about the commercial and social imperative for greater diversity and inclusion, with regard to both the television content produced and the range of people involved in its production. Arguments have been made both in terms of morality and social justice by scholars such as Mark Banks, Shelley Cobb, Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison, Ros Gill, and Anamik Saha, and in relation to market imperatives and competitive advantage by scholars such as Orlando Richard and Carliss Miller. Within the television industry, the emphasis is often on the moral and commercial concerns as indivisible, promoting the fact that “greater creativity and innovation will result from the variety of perspectives, experiences, backgrounds, and work styles that a diverse work-force may bring” (Chrobot-Mason and Abramovich 660). This view is exemplified in the The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC)/Ofcom report on increasing diversity within the UK television industry:

It is important that the most talented people should see a job in broadcasting as a rewarding career choice if our creative sector is to continue to be among the best in the world. Everyone wanting to pursue a career in broadcasting should have a fair and equal opportunity to do so, whatever their background. (“Thinking” 5)

In order to meet these objectives, UK television industry schemes have most typically focused on training and recruitment of a more diverse range of new entrants. The major broadcasters have also introduced additional policies and practices relating to diversity, including quotas in relation to both content and workforce (e.g., the Channel 4 360 Diversity Charter). However, systemic issues of lack of access and exclusion remain. Doris Ruth Eikhof has highlighted the fact that training and access schemes tend to focus on transforming “individuals and their alleged deficiencies”, rather than transforming institutions (303). Others have critiqued the assumption that diverse talent still needs to be “discovered”, arguing that the problem is that it is being ignored, marginalised, or excluded (Coel; Henry and Ryder; Olusoga; “Industry Voices”). Furthermore, the concept of the term diversity is contested and characterised by many different perceptions and understandings of the term (Chrobot-Mason and Aramovich 659; Zanoni et al. 10). This could be as a result of its origins stemming from a business rationale that popularised the notion that a diverse workforce could contribute to the overall economic benefit of a company (Amason 124; Cox and Black qtd. in Zanoni et al. 12; Thomas and Ely 80). Additionally, the business case for diversity extended beyond business strategies and underscored academic research on diversity (Zanoni et al. 12). For example, for Joseph McGrath, Jennifer L. Berdahl and Holly Arrow, the research definition of diversity observes the pitfalls of the visible “demographic difference among members of a group” (22).

Focusing on visible demographic differences crucially overlooks the diverse experiences of the group, while emphasising diverse bodies. Thomas and Ely’s research attempts to address the limitations of visible demographics by suggesting diversity refers to “the varied perspectives and approaches to work that members of a different identity group bring” (80). However, Thomas and Ely’s shift from the pitfalls of visible bodies to a focus on “approaches” to work does little to question the power dynamics central to the work context and, in fact, may reinforce them (Noon 201). In their study of elite occupations in the UK, Friedman and Laurison point out that structural inequalities very often operate tacitly, through cultural norms and practices that exclude and frustrate the progression of those from working-class, female and non-white backgrounds. Some feminist theorists have defined the traditional dominant cultural bias as the “malestream” to describe the masculine rules and norms that lead to the exclusion and marginalisation of women (Beasley 3–4). Meanwhile, Saha, in his examination of race and the cultural industries, argues that techniques such as bureaucratisation, formatting, packaging and marketing, which have been developed to “deal with the inherent unpredictability of the cultural market”, are couched as commercial rather than cultural imperatives, but in fact are underpinned by unacknowledged cultural prejudices (132). Saha’s arguments offer new insights into Ien Ang’s concept of “the imagined audience”, through which, Ang argues, television as an institution attempts to control “the conditions of its own reproduction” (14). Ang proposes that television executives seek to achieve an exhaustive understanding of their audience in order to control its viewing habits. However, this audience is not a pre-existing object so much as a discursive construct, produced through the various techniques of audience measurement that television institutions employ. Following Saha’s arguments, this construct is likely to be the product of a number of unexamined cultural assumptions and stereotypes.

The “glass slipper” has been identified by Karen Lee Ashcraft as a metaphor for explaining the barriers women and marginalised identities face who do not fit into the existing dominant cultural milieu that benefits white men and reproduces inequality (qtd. in Friedman and Laurison 125). Others, such as Halberstam, argue for the unravelling of so called “normal” and limiting heterosexual gendered codes (9). Given the recognition of the influence and impact of such assumptions and stereotypes, it is perhaps not surprising that unconscious bias has been the growing focus of companies, particularly since the Black Lives Matters protests in 2020. Unconscious bias is described as a bias of which we are not in conscious control. It is a bias that happens automatically and is triggered by our brain making quick judgements and assessments of people and situations influenced by our background, cultural environment, and personal experiences (Cornish and Jones 14 qtd in Atewologun, Cornish, and Tresh 10; Lai etal. 1772; Kahneman et al. 4). Attempts to address concerns about how cultural prejudice operates to exclude people of colour and other protected characteristics within the television industry are most evident in the way that many media organisations and businesses have adopted unconscious bias training (Noon 198), particularly with regard to recruitment (“Diversity”). Addressing unconscious bias has also been the subject of critical research and training within work organisations and studies (Lee 2017–56; Devine et al. 1267–78), articulated as producing favourable impacts on members of underrepresented groups (Allen and Garg 1426–32); the reduction of implicit bias (Blair 828–41) and the perspective of the stigmatised other (Galinsky and Moskowitz 708–24) and attitudes (Kahneman et al. 50–60). However, it has equally been critiqued as the foundation for a narrative of psychological and individual rather than structural and political prejudice, which “effectively exonerates governments, institutions, organisations” (Bourne 2).

The arguments outlined above have clear relevance to the practice of ideas development, which sits at the heart of the television production process. Usually, in the initial stage in the creation of a television programme, ideas development is undertaken by media production companies or dedicated in-house broadcaster hubs, with the aim of securing a commission from a television broadcaster, channel or streamer, in order to move to the subsequent stages of pre-production, production and post-production (Brown and Duthie 16). In order to secure a commission, they need to convince those companies that the programme will meet their market imperatives and be successful in attracting a defined audience (30). This process corresponds closely to the “screen idea system” (a reworking of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model of creativity) (Redvall 31). This model posits that, in order to be recognised as creative, any individual work needs to both internalise the principles of an existing domain, which in the case we are discussing would be factual entertainment conventions, and to be approved by the field, which is comprised of the gatekeepers to the domain—in this case television controllers and commissioners (31). Friedman and Laurison’s research into class, which found commissioners have “posh” accents and sit in “by far the most prestigious and powerful department”, underlines the power dynamics embodied in this system (75).

In the account and discussion that follows, we attempt to understand more about the relationship between ideas development, diversity and television structures and processes through the lens of the talent scheme, one of the ways in which the television industry seeks both to open up to new and diverse talent and to induct them into its system.

The Talent Scheme

This scheme, which we will call TDS (Television Development Scheme), selects around sixty participants from the UK. It is not attached to one particular channel or streaming platform, but is funded through a charitable foundation, aiming to provide support across the sector to develop careers in television. A central objective is to identify those who do not already have existing connections or work experience and to help to address the fact that the television industry has been widely acknowledged as predominantly white and middle class. To this end, while the scheme is open to all, rather than targeted towards any specific gender, minority or marginalised group, it aims to recruit as diverse as possible a range of participants. This is achieved through the approach taken to recruitment: working with partner organisations and doing extensive community outreach to make sure that information about the scheme reaches a wide range of potential applicants. In the year that we studied the scheme, 73% of the participants were female, 30% were of colour and 12% were disabled. To monitor the socioeconomic status of participants, the scheme used a range of proxy indicators. This included education and the occupation of the main income earner in participants’ families, as per the UK National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC). Eighty-three per cent of participants had attended a state school and 42% were from families where the main income earner was in a professional occupation. These percentages compare favourably with the 2019 Ofcom monitoring report regarding UK television employment, which found that the UK television industry comprised 45% women, 13% minority ethnic group and 6% disabled, with 74% having attended state school and 60% from a family where the main income earner held a professional occupation (Diversity). It is interesting to note, however, that 95% of the scheme participants had at least an undergraduate degree.

The scheme introduces participants to the industry, giving them training, contacts and experience in television. Our study focused on the idea development strand of the scheme, which introduced participants to the process of idea development in factual entertainment television. We observed development workshops and pitches that were part of a broader range of activities that were offered to participants, including talks and panels from industry speakers and networking events. After this stage of the scheme, participants remained part of a long-term information network, through which they were offered unique access to a range of paid work experience and employment opportunities.

Scope of the Research, Background and Methods

In this case study, we investigate the extent to which the questions and issues discussed above impacted on and were part of the experiences of the participants. We were interested in whether there were any perceivable positive connections between the scope and originality of ideas and the extent to which the teams that produced them were comprised of a diverse range (i.e., with regard to race, gender, cultural background, etc.) of individuals, and also in any potential barriers that might operate to prevent such ideas emerging. Our research was carried out between June and December 2018. We carried out semi-structured interviews with, and surveys of, participants to find out how they experienced the process of working in teams to develop ideas. After the scheme itself had concluded, we interviewed participants who obtained work experience through the talent scheme. We also interviewed television development professionals working with the scheme in a range of roles (such as helping to select candidates, running workshops, giving talks, offering internships or mentoring) about their own experiences of television idea development. In addition, we observed initial selection workshops for the scheme, followed by a series of development workshops for successful participants, and also the resulting pitches to television commissioners, who selected a winning pitch.

Themes

To answer the research question of how diversity might affect the range and originality of ideas developed within the scheme, we had to unpick how diversity intertwines with the ideation process. Five key themes emerged from our research:

1. The Contingent Nature of the Good Idea

The starting point was to understand the criteria, by which both participants and the television professionals involved in their induction into the industry judged ideas. We therefore asked both participants and television professionals involved in the scheme what they thought were the attributes of a good idea. It emerged that they considered what defined a good idea to be neither inherent, absolute, or predictable. While television professionals did highlight such aspects as originality and distinctiveness, they stressed the importance of how an idea was communicated, received, and processed within the structures of television commissioning. As one development producer put it, “a good idea is just anything that you enjoy talking about and brainstorming… but then there are so many steps and processes beyond that idea” (Development Producer 1, white, female). For one creative director, “a good idea is an idea that has clarity to it… if you can say it in a line, that’s what makes a good idea” (Creative Director 2, white, male), while a different creative director told us:

About 10% of it getting commissioned is what the idea is. The rest of it is: what is going on at the channel, who is the label you’re working for, who are the people there who will be making that show. What makes a good idea I think is something distinctive and something new but probably something that doesn’t scare the horses […] a surprising take on something that we know people are interested in. (Creative Director 1, white, female)

Creative Director 2 admitted their frustration at the current commissioning process, suggesting that it limited the possibility for truly original ideas to actually get made into programmes and saying: “We’ve gotta play safe so we are now pitching the safe stuff that we don’t get as excited about” (Creative Producer 2, white, male). These responses suggest that television professionals consider it necessary—although not always possible, or indeed desirable—to try to anticipate in advance what factors might impact on an idea’s reception within the commissioning structure and indeed to build these insights into the inception of ideas.

It was also this aspect of ideas development that TDS participants, as new recruits to the industry, said they had learnt a lot about as part of the scheme, particularly those who went on to carry out work placements. One participant told us:I have been taught all sorts of formats for all kinds of programs and what different channels want and different audiences and I definitely think that my personal idea of what I think I want to make on TV has changed. (TDS Interviewee 3, white, female)

Another who had also undertaken work experience focused more on what she had learnt regarding the importance of how an idea was communicated and understanding the mechanisms of pitching:

When I got here just seeing like their process and seeing how they structured their pitches it just became a lot clearer […] you could see very clearly when you looked at their [pitch] decks—this is kinda how it works. (TDS Interviewee 2, Black, female)

2. Official Machinery

In their discussion of the contingent nature of the good idea, our respondents emphasised their acute sense of the fact that they were participating in a system, outside their control, which would determine how their ideas were judged. It was striking that, whether or not the television professionals we spoke to were sanguine about the situation, they discussed the commissioning system as if the rules and norms were not part of their own world view or practice. One noted: “Effective idea creation is you have to self-edit; you have to be quite critical of your ideas before you present them to other people” (Creative Director 2, white, male).

The idea development process entails a game of second-guessing the gatekeepers’ taste. Within TDS, this had a spiralling effect leading to some self-censorship or explicit censorship at all levels, with TDS applicants wanting to impress the TV producers who were holding the creative idea development workshops, as well as the other members in their group:

As soon as you had two or three women [as on-screen talent], they were like, why do you need an all-female panel, but the prior panel was like four men and nobody said “oh it’s all men on the panel.” And quite interestingly it was women in the group that were making this comment. So being in an environment where everybody’s liberal and diverse. But as soon as women are in the limelight it becomes a girl thing […] and I was more uneasy because it was coming from young girls and I’m thinking well you’re young, and you’re supposed to be different and the patriarchy has really got to your head already. (TDS Interview 2, Black, female)

Another participant, speaking about programming more generally, thought that if the commissioners changed there would be a more diverse range of programmes:

So you’d get less kind of borderline patronising stuff being commissioned […] now the commissioners are like “give (named talent) a show, people love that”, and yeh, it just doesn’t feel like it’s just natural diversity, it’s just forced […] if it changed to… then it would work because then you would have people from diverse backgrounds and they would see if something’s patronising or a bit like stereotypical and they would just say no, this isn’t representative. (TDS Interviewee 4, Asian, male)

Our research points to participants self-selecting ideas to meet the perceived needs of a narrow and elite set of gatekeepers. Rather than inspiring participants to think freely during the brainstorming phase of idea development, it suggests a process at work within groups, in which participants internalise the cultural values of the gatekeepers, thus risking stifling ideas that sit outside of these values and perpetuating a culture of risk aversion:

The word “risk” is bandied around too much and is often used as an excuse for failure of commissioning: safe, bad ideas that are then repackaged as risk because they didn’t work […] You’ve got this army of commissioning editors who are all trying to second-guess what their department head is gonna say, who is then trying to second-guess what the scheduling and the channel head is gonna say. It then has to go to the director of programming but then it has to go to the chief executive of content; there are so many layers. (Creative Director 2, white, male)

3. Diversity Is an Unstable Concept

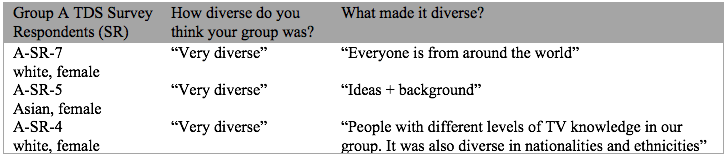

Given the fuzziness of the term “diversity” discussed earlier, it was necessary to survey the participants’ understandings of diversity. The responses revealed a range of perceptions and interpretations of the concept of diversity. However, the majority of participants focused on “visible” diversity rather than inclusive perspectives. The Tables below (1–3) provide a sample of the varied responses from a survey of groups developing ideas during the initial selection workshops.

Group A’s comments explicitly point to the differences in their understanding of diversity including people from around the world to ideas and background (Table 1):

Table 1: Group A’s response to the questions “How diverse do you think your group was?”

and “What made it diverse?”

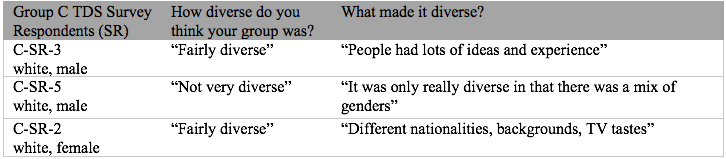

As in the previous example, Group C’s responses highlight the term’s ambiguity in its affirmation of diversity of experience, ideas, and gender (Table 2):

Table 2: Group C’s response to the questions “How diverse do you think your group was?”

and “What made it diverse?”

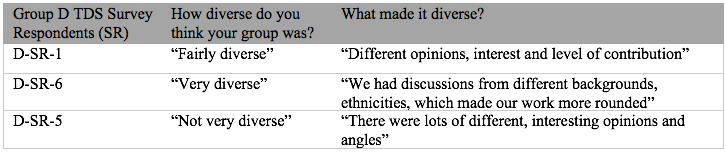

As with Group C, a pattern emerges from Group D that suggests a varied understanding of the term “diverse group”, again linked to ethnicities and ideas (Table 3):

Table 3: Group D’s response to the questions “How diverse do you think your group was?”

and “What made it diverse?”

One survey respondent’s answer we found connected with Thomas and Ely’s use of the term “varied perspectives and approaches”, while other comments from the TDS participants groups A, C and D display an awareness of the concept of a diverse group, which also suggests an acknowledgement of Thomas and Ely’s “different identity groups” but overlooks “varied perspectives and approaches” (80). It is worth noting that a larger proportion of the survey respondents from the underrepresented groups from the Global South linked “diversity of ideas” to different identity groups, while the participants from the global north mostly equated diversity with diverse bodies but did not make the connection to diverse ideas. These comments reflect how the term “diverse group” may reproduce ambiguities that problematise the term’s functionality and operation within the idea’s development process. For example, as one TDS interviewee response indicates:

To be honest, it’s spoken so much now, I’m not sure, like… But I’m… no I’m confused actually, because everything says diversity, I’m like, “What is it?” because, obviously there’s colour, race, etc., there’s culture, yeh. From this task, I guess, you could see different backgrounds, so, different voices, so maybe that’s it, yeh. (TDS interviewee 4, Asian, male)

It would seem that the ambiguities within the term “diverse group” also promotes scepticism that translates into neutralisation within the idea development process. For example, as one TDS interviewee responded:

If we’re speaking about it in terms of race, gender whatever, it was diverse. We had a man, a woman, a person of colour as well, but in terms of characteristics, thought and personality it wasn’t really diverse. (TDS interviewee, 1, Black, female)

Arguably, the instability of the term “diverse group” suggests a connection between ideas and bodies, through which one can be substituted for the other. This confusion limits the term’s effectiveness in the ideas development process.

4. The Norm Prevails

The survey responses offer a glimpse into how the participants understood and approached “ideas” and “opinion” and, as a result, these terms reveal how the instability of diversity as a concept both reflects and shapes the television idea development process

It was quite uncomfortable to talk about anything that wasn’t of the norm… I remember coming out of that thinking, “Hmmm—do I really want to work in development because am I going to be working in teams where I’m going to be this minority where I can’t say anything that isn’t the popular opinion”. (TDS interviewee 2, Black, female)

For so long a lot of people who are people of colour, who are minorities, who are people like Michaela Coel, have been playing a game where they feel like every move they make they end up on a snake and they’re coming down. (TDS Interviewee 1, Black, female)

These statements suggest that the assumption of “norms” are nothing more and nothing less than this: dominant cultural values—a euphemism for male and white. These “norms” are assumed to be universally available and applicable to every participant’s cultural experience. As a result, the instability of diversity presents television “norms” as prevalent, and fundamental in the development process and the participants’ different ideas and opinions as secondary. The instability of the concept of diversity does a disservice to members from marginalised groups. By actually serving dominant cultural values, instead of challenging the “norms” of the television ideas development group, it challenges the different ideas and opinions it was designed to introduce and reflect.

5. Informal Processes

Television culture in general is informal and operates on unwritten rules (Friedman and Laurison 115). Our research pointed to this happening within the idea development process:

I don’t think we have a usual approach to development there’s a small group of us and we each present ideas to each other on an ad hoc basis and then we will talk about it in a very informal way and then we will agree somebody who’s gonna kind of run that and drive it forward to a point of which we feel confident that it’s worked through enough to be able to present it to a broadcaster. (Creative Director 2, white, male)

We found that this informality can reinforce structural inequalities within the television development process. One TDS interviewee told us that because he was from a different background and “watching completely different stuff” to other participants, he might “just concede ideas for the benefit of the team” (TDS Interviewee 4, Asian, male). He went on to explain:

So, I might be like, “Oh I know this comedian who’s really good and he’s someone I watch a lot,” but no one might have heard of him, so he might just kind of get pushed away […] well, people I know have heard of him, but people in the group might not have. (TDS Interviewee 4, Asian, male)

However, despite this internal sense that ideas unknown to the rest of the team would get rejected, the interviewee found that in fact when he nominated a comedian to his team “they were fine, it was just like, ‘Oh we don’t know him, but go for it.’” (TDS Interviewee 4, Asian, male). Another participant, a Black woman, was perceived as “shy” by workshop leaders. However, she told us that her reticence was not an innate personality trait. Rather, it was due to her feeling the need to “walk on eggshells” because of the group dynamics (TDS Interviewee 2, Black, female). These examples illustrate the contradictory experiences of participants when brainstorming in groups, due to the lack of formal processes, suggesting that it is left largely to chance and individuals within a group to determine the ideas that get heard.

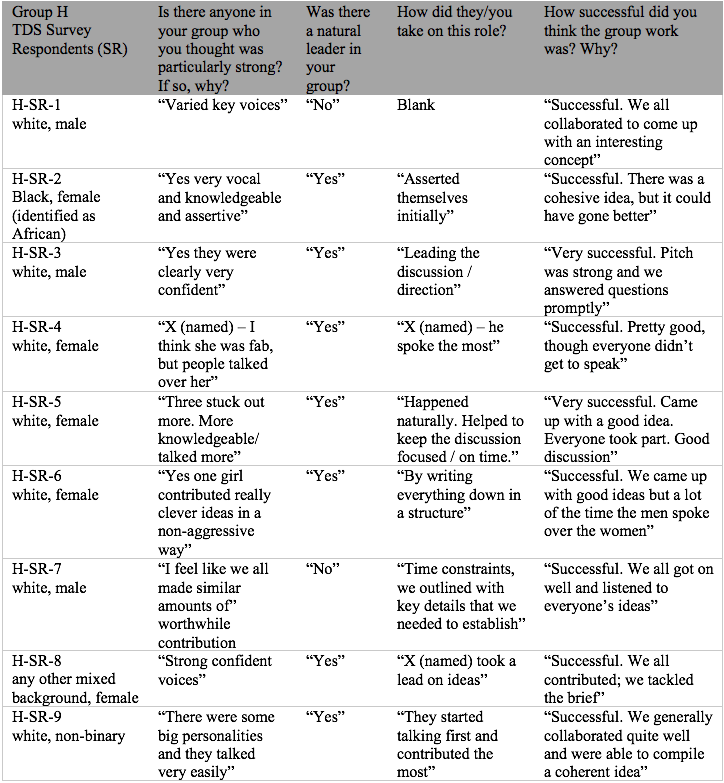

As part of the initial survey, most participants stated that their group was “successful” at working together. However some issues were raised. Table 4 shows the range of views within one group:

Table 4: Group H’s response to the group’s measure of success.

The results demonstrated that many participants identified leaders as those with “big personalities” who “started talking first” (H-SR-9, white, non-binary). However, being vocal was also identified as a barrier to hearing everyone’s ideas “a lot of the time the men spoke over the women” (H-SR-6, white, female) and another noted that “everyone didn’t get to speak” and “people talked over” a Black female participant (H-SR-4, white, female). This is in contrast to the experiences of the White male participants in the group who reported that they “collaborated” (H-SR-1, white male) and “listened to everyone’s ideas” (H-SR-7, white male). Another participant, in a different group, expressed frustration at not being heard:

At first [the group was] trying to narrow down what the brief meant but mostly trying to answer the brief by “ripping up the TV rule book”—I didn’t think that we were doing that, but no one would listen. (G-SR-8, white, female)

The ability to listen to others was attributed by many as the reason for their group’s success at working well together. As survey respondents in group E explained: “We were good at listening and thoughtful with criticism” (E-SR-7, white, female). And this seemed to allow for more space for quieter members of the group to participate: “Noisy types ceded to quieter ones. Good listening and reflecting back of opinions” (E-SR-9, white, female).

These quotes from group E are based specifically on the experiences of working in teams to brainstorm TV ideas and it was notable that some participants mentioned there were instances of stopping people from taking charge. “Someone wanted to be [the leader] but the group didn’t really permit it!” (E-SR-9, white, female). Being vocal is valued by television professionals who are looking for participants who “weren’t afraid to shout out” (Development Producer 2, white, male). This is in contrast to the suspicion of leadership within group E as being about taking over and impeding equal participation: “A couple of people seemed to try to take leadership, but instead it ended up as everyone on an equal platform” (E-SR-5, white and Asian, female). The benefits of no defined leader in this group meant “everyone had their chance to speak” (E-SR-4, Black, male). This shows a level of self-awareness about the value of listening: “I think it [the group] was very successful as we were able to come up with multiple aspects and opinions which needed representing” (E-SR-4, Black, male). This raises the question of whether there should be a leader.

Discussion

At the end of the workshop stage of the talent scheme, the pitch selected as the winner by television commissioners was one that had been developed by a group that was all female and diverse with regard to race, age and regional background (from different regions within England). This would seem to uphold the principle that greater diversity in development teams can have a positive effect on the creativity of the team and the quality of ideas produced. However, the themes we have highlighted above, drawing on the lived experience recounted by some of the participants, demonstrate that substantial barriers also exist to such ideas making their way through the process.

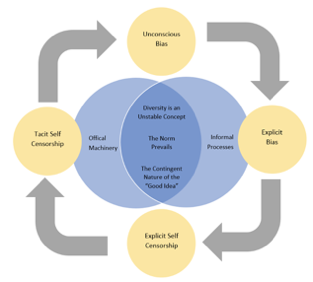

Figure 2 shows a visual representation of different forms of intersecting and overlapping bias that we identified as running through the process of ideas development. Unconscious and unacknowledged assumptions inform the explicit structural and hierarchical rules of engagement through which development teams engage with gatekeepers. Not only do development teams explicitly tailor and modify their ideas to meet the stipulations of the gatekeepers regarding the viewing habits and tastes of the audience, but these stipulations are also often internalised and operate as unexamined norms within development teams. Members of the team from marginalised and underrepresented cultural groups, who have not necessarily internalised these norms, may find their ideas are undervalued or dismissed, or seem simply to go unheard. They often engage in tacit self-censorship in order to fit in.

Figure 2: Differing forms of intersecting and overlapping bias underpinning TV ideas development.

Both the official machinery and the informal processes of ideas development perpetuate a system of risk aversion in which the norm prevails. Our research suggests that new entrants are quickly inducted into this system and required to adapt to its explicit and tacit rules. The attempt to introduce diversity into this well-established system is hampered by the fact that while the system is stable and entrenched, diversity is an unstable concept. Diversity and inclusion have traditionally been associated with the problem of historical, structural racism and sexism and efforts to redress these unfair practices (Ahmed; Grimes; Hunter et al.). However, the ubiquity of the terms in current institutional and cultural discourse can lead to their modification, dilution and abstraction such that, on the one hand they may appear fulfilled merely through the presence of diverse bodies, while on the other, diversity can be used simply to refer to a range of views, without reference to a diversity of cultural backgrounds.

Meanwhile, the experience of actual individuals from marginalised and underrepresented backgrounds is of occupying a racialised, gendered or otherwise othered position, shaped by historical power relations that are longstanding and enduring (Chrobot-Mason and Aramovich; Cobb; Gill; Nkomo and Al Ariss; Saha). When a space in an institution is allowed for diverse bodies but their diversity of experiences and ideas is not given corresponding space, alienation and disempowerment can occur. Individuals are either silenced or take on the heavy physical and emotional burden of fighting to overcome such barriers. Institutional suppression of the experience and agency of marginalised groups is unlikely to be overcome without a conscious effort to go beyond diversity to full inclusion, opening a space that is conceptual as well as physical, within which the experiences and perspectives of currently marginalised groups are fully articulated and acknowledged. However, the dominant cultural norms embedded in the screen idea system mitigate against the opening up of such a space (Redvall 27). As a practical mechanism to manage the stages of production, some version of the screen idea system may be inevitable and indeed necessary, but the efficacy with which television industries’ “risk-reducing techniques and strategies of regulating television programming” (Ang 15) maintain the status quo and perpetuate certain cultural assumptions (Saha) demonstrates why recruiting and inducting a diverse range of individuals into the system as it currently functions is unlikely to produce significant change on its own.

Since the recognition of an idea as good is contingent on the structure and processes of the system, the less open and more infused with risk aversion the system is, the harder it will be for new ideas, embodying a full diversity of perspectives, to emerge from it and be acknowledged as good. If real innovation and diversity of ideas are to be achieved, changes also need to be made at the level of the screen idea system in order to address the structural inequalities it produces.

Conclusion

The risk-averse culture of the contemporary TV industry is evident in the experiences and views recounted by participants in the talent scheme. This suggests that the way that new recruits are inducted into the television industry through talent schemes needs to be addressed, but also that a focus on diversity in recruitment is not enough, since there needs to be a match between recruitment and the wider structures. We suggest that identifying and naming unconscious bias needs to be taken into consideration when creating alternative practices in both the induction of new talent and the idea development process more generally. However, we stress that unconscious bias needs to be seen in relation to historical, structural, gender and racial inequalities, or it risks pushing the responsibility of these processes on to the individual as a solution, while overlooking the normative order within the media industry.

To overcome “bias”, space must be created for diverse bodies and experiences. The concepts of a truly “diverse group” and diverse ideas need to be more transparent and explicit, being more likely to have the same meaning for all involved in the administrating of and participation in the diverse group. Rather than simply providing space for diverse bodies to replicate dominant ideas and experiences propagated by the television industry, a space needs to be created that obliges all participants to search beyond dominant cultural norms for truly diverse ideas.

Recommendations

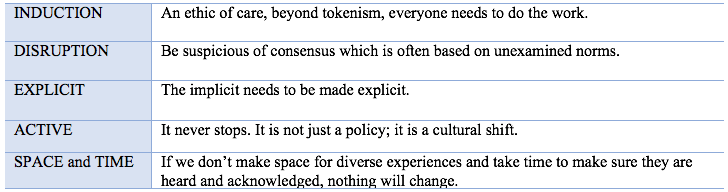

When we presented our research findings to industry leaders, a recurring issue they raised was that introducing procedures to address the lack of transparency and equality embedded in informal processes would protract the whole process. Following the adage “time is money”, they stressed this was time that they did not have. However, we propose that it is simply not possible to create a more inclusive space and disrupt the unexamined norms of informal habitual practices without devoting more time to doing so. We propose an ideas development framework to address barriers to inclusivity in Table 5:

Table 5: Inclusivity Development Framework.

Within the framework above, we highlight the importance of how individuals are induced into a collective, advocating an ethic of care (Bunting; Care Collective; Tronto), by which one does not just assume that equality and inclusion are the automatic foundations of every group. Rather, the mutual interdependence of all group members needs to be acknowledged and material steps need to be implemented to actually ensure equality and inclusion are practised within the group and that everybody does it. This approach conceives induction to be what Haslam et al. have termed:

an inductive process of identity formation, wherein group members interact with one another to develop consensus around new group norms and new understandings of shared social identity—thereby constructing these from the bottom up. (394)

To truly create diverse thinking and inclusion, this approach needs to be embedded in all interactions within the TV development stage; from new entrants to commissioners and from informal processes of brainstorming to the machinery of decision-making. Implicit assumptions and norms need to be made explicit and challenged, giving room to discuss a wider range of experiences and support the needs of everyone present. Different skills need to be emphasised and different practices introduced. Indicative examples include:

Giving listening skills greater priority in the idea development process and practising active listening, i.e., concentrating on what is being said rather than passively hearing the message of the speaker. Not listening when working in a group results in talking becoming a form of silencing. There is no point bringing in diverse voices if they cannot be heard.

Being explicit in how ideas are developed, for example keeping notes on ideas that have been logged, who initiated them, what has been rejected or accepted, and why. These can then be reviewed to discern patterns that might not have been perceived in the moment but may need to be addressed.

The TV industry needs to gain new audiences and create a workplace and culture that is fully inclusive and representative of everybody. This needs to be an active and ongoing process that is constantly renewed, and space and time has to be given to allow for divergent ideas for change to take place. Our intentions are to collaborate with the television industry to put the framework into practice, and continue this research both in the academy and with television industry development teams.

Note[1] Ofcom also regulates radio and broadband and phone networks. At the time of writing, while Ofcom oversees TV on-demand services, this does not include streaming platforms, such as Netflix. However, the UK government is reportedly planning for it do so in the future (Easton).

References

1. Ahmed, Sara.“The Language of Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, 2007, pp. 235–36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870601143927.

2. Amason, Allen C. “Distinguishing the Effects of Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict on Strategic Decision Making: Resolving a Paradox for Top Management Teams.” Academy of Management Journal, no. 39, 1996, pp. 123–48. https://doi.org/10.5465/256633.

3. Ang, Ien. Desperately Seeking the Audience. Routledge, 1991.

4. Atewologun, Doyin, Tinu Cornish, and Fatima Tresh. “Unconscious Bias Training: An Assessment of the Evidence for Effectiveness.” Report No. 113, Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2018, rch-report-113-unconcious-bais-training-an-assessment-of-the-evidence-for-effectiveness-pdf.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov. 2022.

5. Banks, Mark. Creative Justice: Cultural Industries, Work and Inequality. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

6. Beasley, Chris. What Is Feminism Anyway? Understanding Contemporary Feminist Thought. Allen & Unwin, 1999.

7. “The Biggest Challenges.” Broadcast Commissioner Survey, 25 Nov. 2021, www.broadcastnow.co.uk/commissioner-survey/the-biggest-challenges/5165363.article.

8. Blair, Irene. V., et al. “Imagining Stereotypes Away: The Moderation of Implicit Stereotypes Through Mental Imagery.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 81, no. 5, 2001, pp. 828–41. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.828.

9. Bourne, Jenny. “Unravelling the Concept of Unconscious Bias.” Race & Class, vol. 60, no. 4, 2019, pp. 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396819828608.

10. Broadcasting Act 1990. UK Government, UK Public General Acts, 1990, . Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

11. Brown, Lucy, and Lyndsay Duthie. The TV Studio Production Handbook. Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

12. Bunting, Madeleine. Labours of Love: The Crisis of Care. Granta, 2020.

13. The Care Collective (Chatzidakis, Andreas, Jamie Hakim, Jo Litter, and Catherine Rottenberg). The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Independence. Verso, 2020.

14. Chalaby, Jean. “The Rise of Britain’s Super-indies: Policy-making in the Age of the Global Media Market.” International Communication Gazette, vol. 72, no. 8, 2010, pp. 675–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510380800.

15. Chrobot-Mason, Donna, and Nicholas P. Aramovich. “The Psychological Benefits of Creating an Affirming Climate for Workplace Diversity.” Group & Organization Management, vol. 38, no. 6, 2013, pp. 65www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/42/contents9–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601113509835.

16. Cobb, Shelley. “What About the Men? Gender Inequality Data and the Rhetoric of Inclusion in the US and UK Film Industries.” Journal of British Cinema and Television, vol. 17, no. 1, 2020, pp. 112–35. https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2020.0510.

17. Coel, Michaela. “MacTaggart Lecture”. Edinburgh TV Festival 2018, YouTube, 23 Aug. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odusP8gmqsg.

18. Creative Director 1. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown and Rosamund Davies, 5 June 2018.

19. Creative Director 2. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown and Rosamund Davies, 12 June 2018.

20. Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention. 1997. Harper Collins, 2013.

21. Development Producer 1. Interview. Conducted by Rosamund Davies, 23 Aug. 2018.

22. Development Producer 2. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown, 14 December 2018.

23. Devine, Patricia G., et al. “Long-term Reduction in Implicit Race Bias: A Prejudice Habit-breaking Intervention.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 48, no. 6, pp. 1267–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003.

24. “Diversity in Practice: in Production.” Creative Diversity Network, creativediversitynetwork.com/diversity-in-practice/production. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

25. Easton, Jonathan. “Streamers Operating in the UK Set to be Regulated by Ofcom.” Digital TV Europe, 21 June 2021, www.digitaltveurope.com/2021/06/21/streamers-operating-in-uk-set-to-be-regulated-by-ofcom.

26. Eikhof, Doris Ruth. “Analysing Decisions on Diversity and Opportunity in the Cultural and Creative Industries: A New framework.” Organization, vol. 24, no. 3, 2017, pp. 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508416687768.

27. Equality Act 2010. UK Government, UK Public General Acts, 2010, www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.

28. Friedman, Sam, and Daniel Laurison. The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to be Privileged. Policy Press, 2019.

Galinsky, Adam. D., et al. “Perspective-taking: Decreasing Stereotype Expression, Stereotype Accessibility, and In-group Favouritism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 78, no. 4, 2000, pp. 708–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708.29. Gill, Ros. “Unspeakable Inequalities: Post Feminism, Entrepreneurial Subjectivity, and the Repudiation of Sexism Among Cultural Workers.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, vol. 21, no. 4, 2014, pp. 509–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxu016.

30. Grimes, Diane Susan. “Challenging the Status Quo? Whiteness in the Diversity Management Literature.” Management Communication Quarterly,vol. 15, no.3, 2002, pp. 381–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318902153003.

31. Hackett, Ruth A., et al. “Disability Discrimination and Well-being in the United Kingdom: A Prospective Cohort Study.” British Medical Journal, vol. 10, no. 3, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035714.

32. Halberstam, Jack. Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender, and the End of Normal. Beacon Press, 2012.

33. Haslam, Alexander S., et al. “The Collective Origins of Valued Originality: A Social Identity Approach to Creativity.” Personality and Social Psychology Review, vol. 17, no. 4, 2013, pp. 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313498001.

34. Henry, Lenny, and Marcus Ryder. Access All Areas: The Diversity Manifesto for TV and Beyond. Faber, 2021.

35. Hunter, Shona, et al. “Introduction: Reproducing and Resisting Whiteness in Organizations, Policies, and Places.” Social Politics, vol. 17, no. 4, 2010, pp. 407–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxq020.

36. “Industry Voices: Videos” Screen Industries Growth Network (SIGN), screen-network.org.uk/videos. Accessed 21 June 2021.

37. Kahneman, Daniel, et al. “The Big Idea: Before You Make that Big Decision.” Harvard Business Review, vol. 89, no. 6, 2011, pp. 50–60.

38. Lai, Calvin K., et al. “Reducing Implicit Prejudice.” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, vol. 7, no. 5, 2013, pp. 315–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12023.

39. Lee, Cynthia. “Awareness as a First Step Toward Overcoming Implicit Bias.” Enhancing Justice: Reducing Bias, edited by Sarah E. Redfield, GWU Law School, Public Law Research Paper No. 2017–56, 2017. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3011381.

40. McGrath, Joseph, et al. “Traits, Expectations, Culture and Clout: The Dynamics of Diversity in Work Groups.” Diversity in Work Teams: Research Paradigms for a Changing Workplace, edited by Susan E. Jackson and Marian N. Ruderman, American Psychological Association Washington, DC, 1995, pp. 17–45.

41. “The National Statistics Socio-economic classification (NS-SEC).” Office of National Statistics, UK Government, United Kingdom, 2010, www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/otherclassifications/

thenationalstatisticssocioeconomicclassificationnssecrebasedonsoc2010. Accessed 11 Nov. 2022.42. Nkomo, Stella M., and Akram Al Ariss. “The Historical Origins of Ethnic (White) Privilege in U.S. Organizations.” Journal of Managerial Psychology, vol. 29, no. 4, 2014, pp. 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2012-0178.

43. Noon, Mike. “Pointless Diversity Training: Unconscious Bias, New Racism and Agency.” Work, Employment and Society, vol. 32, no. 1, 2018, pp. 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017719841.

44. Ofcom. “Diversity and Equal Opportunities in Television: Monitoring Report on the UK-based Broadcasting Industry.” United Kindom, 18 Sept. 2019, www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/166807/Diversity-in-TV-2019.pdf.

45. Olusoga, David. “James MacTaggart Lecture.” Edinburgh TV Festival 2020, YouTube, 24 Aug. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XALf10024r8O.

46. “Population of England and Wales.” UK Government, Ethnicity Facts and Figures, 7 Aug. 2018, www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest.

47. Redvall, Eva Novrup. Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark: From The Kingdom to The Killing. Palgrave, 2013.

48. Richard, Orlando C., and Carliss D. Miller. “Considering Diversity as a Source of Competitive Advantage in Organizations.” The Oxford Handbook of Diversity and Work, edited by Q. M. Roberson, Oxford UP, 2013, pp. 239–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199736355.013.0014.

49. Saha, Anamik. Race and the Cultural Industries. Polity Press, 2018.

50. Siddique, Haroon. “Minority Ethnic Britons Face ‘Shocking’ Job Discrimination.” The Guardian, 17 Jan. 2019. www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/17/minority-ethnic-britons-face-shocking-job-discrimination.

51. TDS Interviewee 1. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown and Rosamund Davies, 23 Aug. 2018.

52. TDS Interviewee 2. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown, 14 Dec. 2018.

53. TDS Interviewee 3. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown, 28 Nov. 2018.

54. TDS Interviewee 4. Interview. Conducted by Lucy Brown and Rosamund Davies, 23 Aug. 2018.

55. TDS Survey. Conducted by Lucy Brown and Rosamund Davies, June and July 2018.

56. “Thinking Outside the Box: Supporting the Television Broadcast Industry to Increase Diversity.”The Equality and Human Rights Commission and Ofcom, Aug. 2015 (updated Mar. 2019), www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/thinking-outside-the-box-increasing-diversity-television-broadcasting-industry.pdf. Accessed 30 Jan. 2022.57. Thomas, D. A., and Robin Ely. “Making Differences Matter: A New Paradigm for Managing Diversity.” Harvard Business Review, 74, no. 5, Sept.–Oct. 1996, pp 79–90.

58. “360° Diversity Charter.” Channel 4, United Kingdom, 12 Jan. 2015. www.channel4.com/media/documents/corporate/diversitycharter/Channel4360DiversityCharterFINAL.pdf.

59. Tronto, Joan, C. Caring Democracy. Markets, Equality and Justice. New York UP, 2013.

60. Zanoni, Patricia, et al. “Guest Editorial: Unpacking Diversity, Grasping Inequality: Rethinking Difference through Critical Perspectives”, Organization, vol.17, no. 1, 2010, pp. 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508409350344 .

61. Zwysen, Wouter, et al. “Ethnic Penalties and Hiring Discrimination: Comparing Results from Observational Studies with Field Experiments in the UK.” Sociology,vol. 55, no. 2, 2021, 227–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520966947.

Suggested Citation

Brown, Lucy, Rosamund Davies, and Funke Oyebanjo. “Recognising and Addressing Unconscious Bias and Structural Inequalities: A Case Study Within Television Idea Development.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 24, 2022, pp. 97–117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.24.06

Lucy Brown is Head of Film at London South Bank University, and an award-winning practitioner and educator. She has taught at film schools across five continents and is the Founder and Chair of Women in Screen and the Trailblazing Women On and Off Screen conference. Lucy sits on the editorial board of Representology: The Journal of Media and Diversity. Her 2021 documentary on Thelma & Louise has screened globally picking up Best Mobile Short and International Producer awards. She is author of “Script Development on Unscripted Television” in The Palgrave Handbook of Script Development and co-author of The TV Studio Production Handbook (Bloomsbury).

Rosamund Davies is Senior Lecturer in Screenwriting with a background in professional practice in the film and television industries, in which she worked with both independent production companies and public funding bodies as a script editor and story consultant. Rosamund is a member of the International Screenwriting Research Network and a contributor to the Journal of Screenwriting. Recent publications include Introducing the Creative Industries, SAGE 2013 (with Gauti Sigthorsson) “The Screenplay as Boundary Object” in Journal of Screenwriting (vol. 10, no. 2, 2019) and “Trapped: A Case Study of International Co-production” in The Palgrave Handbook of Screen Production, Palgrave 2019.

Funke Oyebanjo is a script consultant, lecturer and scriptwriter and web fest curator for the Raindance Film Festival. She was one of the founder members of the Talawa theatre writers’ group. Her television script The Window was produced for Channel Four’s Coming Up season and she currently has three screen features in development. One of her projects The Land, was selected by Script House, for development at the Berlin film festival’s talent campus. Funke has worked as a script reader and development consultant with Arena Majicka in Norway, BBC Writer’s Room, BBC World Service, The UK Film Council, Creative England.