Home as Survival: Seeing Queer Archival Lives

Jennifer Cazenave

[PDF]

Abstract

As a teenager in the eighties, French filmmaker Sébastien Lifshitz scoured flea markets for amateur photographs. In 2013, he assembled a book titled The Invisibles comprised of snapshots depicting queer lives. He included a pair of Kodachrome images, which replicate a near-identical domestic scene in the 1960s: two aging women in their bourgeois home sit at a table, embracing as they look at the camera. Taking as a point of departure these personal photographs, this article focuses on two documentaries that queer postwar domesticity: Lifshitz’s The Invisibles (2011) and Magnus Gertten’s Nelly and Nadine (2022). In his film, Lifshitz not only includes postwar snapshots and home movies, but also reinvents the amateur dispositif. He interviews queer aging men and women inside their homes, challenging social exclusion and stigma based on gender nonconformity and aging. In Nelly and Nadine, a sexagenarian named Sylvie retrieves home movies from her attic that uncover a lesbian love story between her grandmother Nelly and a fellow survivor of Ravensbrück named Nadine. Decades later, the centrality of the domestic space and the amateur archive in these two documentaries offers a lesson in seeing the home as survival and unlearning the master narratives of the postwar era.

Article

In 2013, French filmmaker Sébastien Lifshitz published The Invisibles, a book of amateur images depicting the everyday life of same-sex couples and crossdressers throughout the twentieth century. Near the middle of the book, two Kodachrome photographs—immediately recognisable as 1960s artifacts—have been placed side by side as they might have been in their original family album. Captured on different days, this pair of colour snapshots replicate a near-identical domestic scene: two aging women in their French bourgeois home sit at the table after a meal, embracing as they look directly at the camera. In his introduction, Lifshitz singles out these personal photographs, which were part of a collection of eleven family albums spanning thirty years. Purchased decades earlier at a flea market, they offered the future filmmaker a first lesson in seeing queer archival lives. “The images weren’t extraordinary in any way, but I was very quickly drawn to a detail,” he writes. “I was unable to discern the nature of the relationship between these two women: were they two sisters, two friends, or two lovers?” (par. 2).

Perusing the family albums, Lifshitz understood very quickly that the two sexagenarians were, in fact, a couple. What he found most remarkable was how these snapshots both replicated and disrupted the conventions of a postwar visual culture that celebrated heteronormative domesticity. In an era when people who identified as gay or lesbian existed as “the invisibles” of French society, the two women moved from the margins to the centre: they queered the normative image of home typically “imprisoned within the nuclear family”, all the while running the risk of being outed every time a roll of film had to be developed (Zimmerman, “Morphing” 276). In the twenty-first century, these Kodachrome photographs return as orphaned artifacts of queer documentation. Accordingly, their entry into the archive functions as a coming out: a movement toward cultural visibility and a process of unlearning the master narrative of compulsory heterosexuality.

In the 1960s, Kodachrome offered a new way of seeing the world. This mass-market version of colour photography captured a postwar era invigorated by a vivid palette, which further idealised the nuclear family. At the same time, the medium’s unique archival stability—properly stored Kodachrome could last one hundred years—opened new vistas for future memory-making that rendered the undoing of cultural erasure possible. The publication of The Invisibles, which coincided with a domestic turn in queer theory, came shortly after Kodachrome was discontinued in 2010. The two colour snapshots Lifshitz chose to include themselves offered a new way of seeing the home that accounted for the overlooked or socially marginalised. During the postwar era, the domestic sphere and the amateur image constituted rare spaces where the lesbian couple could socially exist: where they could pose together in front of others and show signs of physical affection. Rather than the negative experience of being closeted, these personal photographs preserved an interior filled with objects and furniture that draws attention to a lifelong partnership of nonconformity; to the construction of a hospitable world in the face of exclusion; and to the possibility of survival—what Lee Wallace describes as “queer domesticity, its ephemerality and material persistence” (207).In a book largely comprised of unrelated and undated black-and-white snapshots, the two Kodachrome photographs stand out as historical markers of a particular period in France’s history: the “Trente Glorieuses”, the so-called glorious thirty years of rapid economic growth, modernisation, and social progress following World War Two. The expression Trente Glorieuses was coined by French economist Jean Fourastié in The Glorious Thirty, or the Invisible Revolution from 1946 to 1975, a book originally published in 1979. Today, only remembered by its abbreviated title, the book cemented the periodisation of 1946 to 1975, effectively cutting with the dark years of collaboration that divided the French nation. Portrayed as an inevitable march toward progress and a celebration of national unity, the master narrative put forward by Fourastié remains largely taken for granted. Only in the past decade have French historians begun to recover the less “glorious” facets of economic prosperity and social conformity, from ecological destruction to the exploitation and exclusion of immigrants. They have also rejected the representation of the postwar era as an “invisible revolution” supposedly met with the silence of national consensus. Instead, the Trente Glorieuses resounded with resistance and dissent—with protests and counter-representations—marginalised by Fourastié after the fact (Pessis et al. 11).

In the twenty-first century, the colour portraits of the two sexagenarians further contrast with the many amateur photographs found in The Invisibles, which depict youthful bodies and desires, as well as wedding ceremonies suggesting a life to come. Yet, Lifshitz’s introduction leaves unacknowledged all the ways in which the pair of snapshots offers a lesson in unlearning “the master narrative of decline” associated with aging (Gullette 138). These private artifacts resist the compulsory youthfulness of the 1960s, evidenced in the proliferation of home images that traditionally celebrated the blissful everyday life of young families: “baby’s first step, not fighting with the adolescent; vacation, not work; wedding parties, not divorce proceedings; births, not funerals” (Citron 19). Half a century after being processed, the two Kodachrome photographs revise our notion of home images to account for doubly marginalised bodies and desires: queer and aging lives in the Trente Glorieuses. Their entry into the archive unsettles the “supposed invisibility” of compulsory heterosexuality and able-bodiedness, which continue to pass as “the natural order of things” (McRuer 1).

Lifshitz published The Invisibles two years after the release of a documentary bearing the same title that centres on middle-aged and elderly individuals, either lesbian, gay, or bisexual. His French subjects, aged sixty to ninety, were born between 1919 and 1939; they all reached adulthood during the homophobic Trente Glorieuses. In the film, Lifshitz omits his protagonists’ names until the closing credits, recalling anonymous postwar home movies that universalise the cultural ideal of the nuclear family. He also addressesthe loss of gay and lesbian history through radical visibility: he interviews his subjects inside their homes, defying past exclusion and stigma based on gender nonconformity and aging. Beyond this double meaning of “invisible”, the title of the film confronts the difficulty of documenting the queer everyday—whether inconspicuous lives confined to the domestic sphere or the less obvious experience of trauma as social injury (Cvetkovich, Archive 3).

Taking as a point of departure the centrality of aging queer bodies in The Invisibles, this article investigates how amateur images “challenge nationalist representations of sameness” (Zimmerman, “Morphing” 276) to expose the trauma of compulsory heterosexuality and able-bodiedness. I read Lifshitz’s impulse to collect personal photographs and create alternative histories of queer life in postwar France alongside Magnus Gertten’s documentary Nelly and Nadine (2022), which also tells the story of “the invisibles”. This simple yet aptly titled film claims archival status for a personal collection of home movies and paper documents generated by a love story between two aging lesbians—both survivors of Ravensbrück—living in exile in the 1950s and 60s. In focusing on the creation of queer archives against the backdrop of the Trente Glorieuses, this article proposes to reconsider the postwar home as a site of survival: the possibility of belonging in the past and memory-making for the future.

Queer Archiving

Exploring the role of photography in creating archives of the overlooked or marginalised, Ann Cvetkovich remarks: “Queers have long been collectors because they are not the subject of official histories and thus have to make it themselves by saving materials that might be seen as marginal. […] To love the wrong kind of object is to be queer (as is perhaps an overattachment to objects in the first place)” (“Photographing” 275). A gay filmmaker born in 1968, Lifshitz has long been a collector and curator of amateur images. He began amassing snapshots when he was a teenager in the early 1980s. Years later, he continued to search for personal photographs and family albums in flea markets and garage sales in France and abroad.

Lifshitz came of age during the first decade of the AIDS epidemic when mainstream media pathologised gay subjects, rendering them at once visible and invisible, spectacular and stigmatised. In this era, “[h]omosexual bodies were put on display as a traumatizing threat to the general public, while traumatized queer lives were discounted” (Hallas 17). Decades later, the collective trauma of AIDS still haunts the queer amateur archive created by Lifshitz, which he has since publicly circulated in the form of books and exhibitions.[1] Following the publication of The Invisibles, he remarked: “AIDS killed so many of the generation before me, so there is no one to pass down that legacy. A lot of gay people my age feel a bit orphaned” (qtd. in Radnor). Confronted with historical loss, he constructed an alternative world of kinship across countries and generations while giving a home to seemingly insignificant images long neglected by official archives.The snapshots collected in The Invisibles repair the dominant media representations of an entire century, throughout which homosexuality was embodied and pathologised as a negative image: a deviance, a menace, an abnormality.[2] By contrast, the (invisible) master narrative of compulsory heterosexuality was repeatedly reaffirmed and celebrated in everyday life, notably through amateur images that cultivated cultural conformity. In the postwar era, the snapshot and the home movie reproduced the nuclear family through iconic images of blissful domesticity: birthday parties, Christmas mornings, and summer vacations. Tightly framed, this visible evidence of national belonging seemingly protected the healthy nuclear family from its contaminated others. It demarcated the “natural” inside from the “unnatural” outside, the heteronormative centre from the abject margin (Fuss 2).

Lifshitz assembled the orphan images in The Invisibles as one would a family album. The reader moves from one unnumbered page to the next, encountering repeated scenes of domestic bliss and cultural conformity (albeit sanschildren) characteristic of the conventional snapshot image: a male couple on their front porch with an American flag flying behind them; a crossdresser in their kitchen; two young women getting married in their backyard; a bourgeois couple on a seaside holiday; two men embracing by a Christmas tree. At once ordinary and extraordinary, these private artifacts affirm domestic normalcy while disrupting the very norms of the heterosexual nuclear family that snapshot photography typically reinforces (Zuromskis 7). In the twenty-first century, they offer a lesson in seeing everyday image-making to account for self-representation and survival against the grain of conformity: what Lynn Spigel terms “a home-mode antidote” to social exclusion and erasure through the creation of personal photographs that transformed the postwar domestic interior into a site of resistance (13).

Recasting the “Trente Glorieuses”

In 2011, when Lifshitz released his documentary The Invisibles, hebroke the silence and anonymity of the amateur archive he had assembled over the years, specifically the family albums that queered the bourgeois interior of the Trente Glorieuses. On camera, the aging men and women he interviewed recount their lives as sexual minorities in a postwar period traditionally narrated in two parts: on the one hand, the consumer and conformist France of the 1950s and 60s, which celebrated hygiene, the middle-class home, and the figure of the housewife; on the other, May 1968 and after. In the film, the expression Trente Glorieuses is never uttered. Through this silence, Lifshitz deviates from the master narrative to recount a different “invisible revolution”, one comprised of individuals orphaned by compulsory heterosexuality and homophobia.

The Invisibles resists the rigid periodisation of 1946 to 1975, opting instead for a more inclusive frame. The documentary traverses all three decades of the postwar era, discreetly arriving at 1981, on the threshold of the AIDS crisis and the decriminalisation of homosexuality in France. Lifshitz does retain the iconic year of 1968 as a marker of change that fuelled movements to depathologise queer identities over the next decade. Several interviewees recall the spectacular entry of homosexuals into the realm of the culturally visible and the concomitant exposure of compulsory heterosexuality as a bourgeois construct hidden in plain sight. Left off-frame but intimated in this visibility is the fact that “May ’68 forgot homosexuality in its smoke-filled meetings”, as students supposedly on the side of revolt tore down handwritten notices denouncing the repression of homosexuals from the walls of the occupied Sorbonne (Martel 15–16).

As a collector, Lifshitz decided only to interview individuals who had a family archive of their own that he could use in the documentary (Chareyron 188). In contrast to the photo album published two years later, many of the personal snapshots and home movies he included in The Invisibles capture seemingly happy lives, but are bounded by a heteronormativity that obscures queer bodies, desires, and identities. In the film, the story of the idealised nuclear family of the Trente Glorieuses is told in tandem through the testimonies and domestic archives of Thérèse Clerc, a well-known militant feminist in her eighties, and Christian, a middle-aged gay man from Marseille.

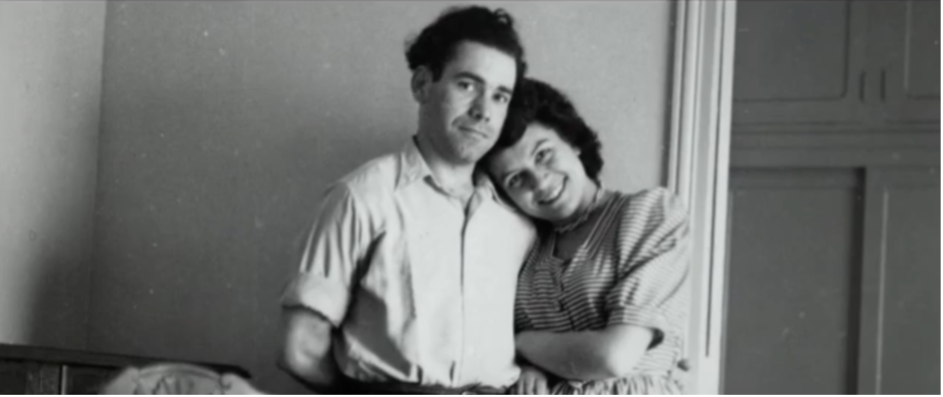

Thérèse and Christian are parallel protagonists: their individual interviews follow each other in the first half of the film, during which they recount their childhoods and early adulthoods. Through the editing, their postwar lives and amateur archives appear interchangeable, invisibly bound by compulsory heterosexuality: black-and-white snapshots of Thérèse as a newlywed housewife in the late 1940s are accompanied by a cheerful piano tune that continues to play as the film cuts to Christian returning to the now-abandoned family home of his postwar childhood. Later, a seamless transition set to the same tune blends a black-and-white home movie of Thérèse as a young mother with Super 8 mm footage of Christian’s family home.

Figures 1 and 2: Two black-and-white snapshots of domestic bliss showing Thérèse and her husband

as newlyweds (top) and Thérèse holding her new-born son (bottom) included in

Sébastien Lifshitz’s The Invisibles. Peccadillo Pictures, 2012.Screenshots.

Separately, Thérèse and Christian each describe the home pictured in these amateur images as a site of confinement: a rigid domestic frame that, cut off from alternative narratives and counter-memories, violently restricts bodies to the heteronormative order. “I realised very quickly that I was going to be shut in for years”, Thérèse remarks, upon recalling her life as a housewife, feeling condemned to invisible labour inside the home, expected only to raise her four children. “It was a dull ache, I never gave it a name”, she adds, designating a repression that could not be socially expressed in the Trente Glorieuses. For Christian, who comes of age as a gay man in the 1970s, home is a place where he is inevitably closeted, his sexuality silenced as he is expected to conform to bourgeois values and gender roles celebrated by a homophobic postwar society, of which his family is a microcosm.

Neither protagonist ever comments on the home images that Lifshitz juxtaposes with their talking-head interviews. Instead, their testimonies function to break the silence of the postwar domestic archive. For both, compulsory heterosexuality engendered a sort of death: “a premature aging” (to quote Christian) that contrasted with the images of youthful bodies captured in snapshots and home movies. They survived this social injury, escaping in radically different ways. Christian kept his identity secret throughout the 1970s, traveling the world and taking photographs.[3] He was outed in a 1979 reportage published in Paris Match, the emblematic illustrated magazine of the postwar era, of which his bourgeois mother was an avid reader. By contrast, May 1968 irremediably altered the life of Thérèse: she divorced her husband a year later and came out against the backdrop of the women’s liberation movement. She concomitantly transformed her home into a site of resistance, performing clandestine abortions in her apartment—another “invisible revolution” culturally erased from the master narrative, which was criminalised in France until the passage of the Veil Law in 1975.

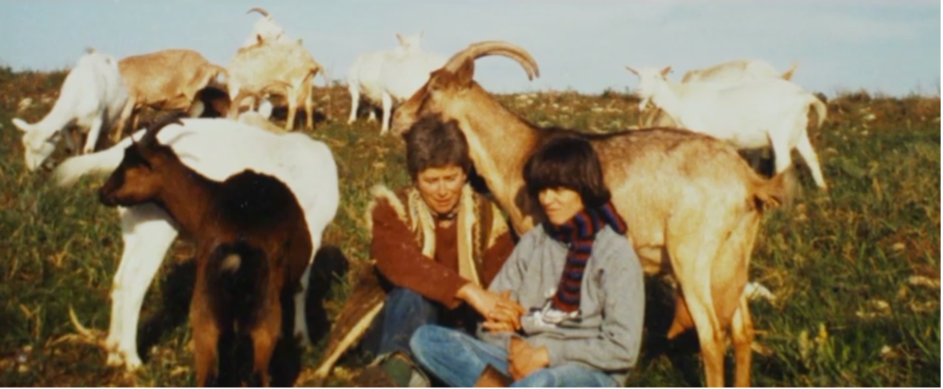

As a work of repair, Lifshitz’s documentary includes snapshots that bear witness to queer domesticities, such as colour photographs of a happy, aging Thérèse at home in the decades following May 1968, or the family albums of Babette and Catherine, a lesbian couple who started a goat farm after experiencing workplace discrimination in the 1970s. He further counters postwar cultural invisibility through archival footage depicting the vocal and visible protests of feminist and gay-rights movements in the streets of France. In the present, Lifshitz’s own camera inscribes the bodies of his protagonists into public spaces they had passed through unseen and unacknowledged decades before, at a time when “coming out of the closet also had its limitations: it meant entering the ghetto” (Martel 155). Attending to the everyday, Lifshitz records banal scenes, such as Christian swimming and sunbathing at a public outdoor pool or Bernard and Jacques, the oldest couple in the film, grocery shopping and affectionately walking together in the street.

Figure 3: A colour snapshot of Babette (left) and Catherine (right) with their goats included in

The Invisibles. Peccadillo Pictures, 2012.Screenshot.

The filmmaker further mediates cultural visibility in The Invisibles through thetalking-head interview, a visual convention that “is as much part of the hegemonic media discourse as it is of politically committed documentary” (Hallas 40). This testimonial encounter creates a portrait of survival—accentuated by the subjects’ aging faces—within a collective history haunted by the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 90s, an era entirely left off-frame in Lifshitz’s contemporary documentary. In response to the epidemic, queer media makers interrupted the dominant representation of the objectified other, notably by reinventing the talking head through performance and reappropriating home video technology to document illness and bear witness to trauma (Hallas 37, 115).In 2011, two years before France legalised same-sex marriage, Lifshitz reimagined the silent home movie as an inclusive frame. The Invisibles opens with the unusual image of a baby bird hatching under the care of gay couple Yann and Pierre—rather than the birth of a baby, “one of the primary motivations for purchasing a camera” in the postwar era (Citron 7–9). Lifshitz further queers the normative use of home movies in omitting young children entirely and rewriting kinship.[4] Much like the reimagined family album published two years later under the same title, The Invisibles fosters a sense of belonging, notably for a filmmaker left orphaned by the AIDS epidemic. In fact, the documentary creates an alternative community missing during the Trente Glorieuses. A certain closeness between the (invisible) younger filmmaker and his (visible) older subjects permeates the film, evidenced by their use of “tu”,the informal French “you”, when speaking to him. In turn, Lifshitz’s moving portraits of aging queer individuals inside the domestic sphere themselves emphasise care and intimacy: what Cvetkovich describes as “feelings that are not visible as such but embedded in the loving attention to surface detail and presentation” (“Photographing” 278).

In the film, Lifshitz combines archival images and talking-head interviews to create representations and memories of aging that address the traumatic exclusion underpinning compulsory able-bodiedness. “[V]isibly marked aged bodies”, Kathleen Woodward writes, “are typically considered so ordinary that they recede from view, becoming invisible” (33). The filmmaker subtly includes segments of reportage from the Trente Glorieuses, in which elderly women watching an abortion rights protest from the sidelines unhesitatingly express their support upon being interviewed. Within the domestic sphere, his camera lovingly renders visible the bodies of his elderly protagonists, such as Thérèse getting her toenails painted red before a dinner party or Bernard entering the hallway in his underwear.

In bearing witness to a queer and aging existence, The Invisibles resists a master narrative of decline that naturalises the isolation of the elderly: individuals confined to the private realm, their bodies “invisible to most other people” (Lindemann Nelson 89). Rather than offer a single story of old age, however, Lifshitz composes The Invisibles from manifold narratives: Jacques, who came out at the age of seventy-one when he fell in love with Bernard; Pierrot, an eighty-three-year-old bisexual peasant who describes his desire in the present tense; Monique, an aging lesbian who remembers the sadness and loss she experienced upon turning fifty when she no longer perceived herself as physically attractive. Toward the end of the film, it is also Monique who lingers on the cruel passage of time: standing in front of the now unrecognisable home of her childhood, she recalls invisible memories and missing protagonists, echoing an anxiety of transmission palpable in Lifshitz’s portrait of queer survival during the Trente Glorieuses.

Figure 4: Bernard (left) and Jacques (right) having tea in their living room in The Invisibles.

Peccadillo Pictures, 2012.Screenshot.

Repairing Postwar Silence

Picture this:in the early sixties, a Super 8 camera films a bourgeois interior reminiscent of the two snapshots found by Lifshitz. Paintings and sculptures adorn the bedroom walls, while framed black-and-white photographs and antique vases have been placed on a dresser. Immediately after, the silent home movie cuts to a close-up of a sexagenarian as she lights her cigarette. This static shot introduces the woman behind the camera: her name is Nadine Hwang. In the next scene, she returns to the bedroom, where another older woman in a navy blue dress now sits, knitting. She looks up at the camera, visibly talking to Nadine: her name is Nelly Mousset-Vos. The silent colour footage then cuts to a different day where the two women are giving a tour of their living room to a younger French gay man named Raymond. As Nadine points to an oval painting on the wall, her other hand rests on the back of a chair, discreetly touching Nelly’s. A few instants later, the couple and their guest are filmed at the dinner table talking and laughing. In the last scene, Nelly sits next to Nadine, who sets up the projector to screen her amateur films for their friends.

“In my family there were always home movies: shooting them and watching them”, Michelle Citron recalls of her American childhood in the early fifties (8). The Super-8 footage described above repeats this domestic convention naturalised in postwar everyday life. At the same time, the amateur films of Nelly and Nadine reconfigure the dominant model of domesticity and its family-centred representation. The two protagonists are an aging, childless lesbian couple. Their bourgeois home is at once familiar and unfamiliar, recognisable all the while exposing what has been constructed as invisible: the tight (and exclusive) frame of the presumably heterosexual nuclear family routinely pictured through the father’s gaze. The flickering home images captured by Nadine in the 1960s reimagine the interior past and the auteur. The colour footage expands postwar family togetherness to account for queer archival lives, which relate to each other in ways “that are neither predictable nor containable within straight ideologies of domesticities” (McRuer 102).

Figure 5: Home movie footage of Nelly (left), Nadine (centre), and Raymond (right) at the dinner table included in Nelly and Nadine (2022) by Magnus Gertten. Screenshot. Used by permission of Auto Images.

Intimated in these Super 8 mm reels is an understanding of home as a site of resistance as well as survival. Much like the two Kodachrome photographs, the amateur films of Nelly and Nadine could have been captured anywhere in postwar France. They were, in fact, recorded thousands of miles away in Caracas, Venezuela, far from the homophobia of the Trente Glorieuses. It was there that the couple relocated in 1950 and remained for nearly twenty years. They had carried with them not only the trauma of the camps but also the social injury of being “the invisibles”. In exile, they countered postwar erasure and silence, creating memories for a more capacious future in the form of home movies and an unpublished wartime memoir preserved in a trunk, which remained unopened for decades.In the twenty-first century, the story of Nelly and Nadine begins on a farm in northern France where their domestic archive lies dormant. The Swedish filmmaker Magnus Gertten arrived there by way of two documentaries, Harbour of Hope (2011) and Every Face Has a Name (2015), which centred on women survivors seen in a silent black-and-white newsreel recorded on 28 April 1945 in the port city of Malmö, Sweden. The camera captured many close-ups, among them the face of Nadine. She had been rescued only days before from Ravensbrück by the Swedish Red Cross. In the archival footage, she stands surrounded by three other women, two of whom are smiling. Nadine is the only one still wearing a striped prisoner uniform jacket from the Nazi concentration camp, affirming her status as a survivor. In that moment, she is also the only one staring intently at the camera, fully aware that they are being filmed.[5]

Figure 6: A black-and-white closeup of Nadine Hwang in April 1945 included in

Nelly and Nadine. Auto Images, 2022. Screenshot. Used by permission of Auto Images.

Her returned gaze is at once intimate and unfixable: is it an act of self-affirmation after having been dehumanised in the concentration camp? Is it a question, one that asks where the camera was when the women had been imprisoned at Ravensbrück, invisible to the rest of the world? Is it a form of bearing witness in the aftermath of collective silence and erasure: a means of belonging anew in the present and creating memories for the future?

The story of Nadine is, in part, the story of a reparative archival impulse: what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes as “a project of survival […] in which selves and communities succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture—even of a culture whose avowed desire has often been not to sustain them” (35). Nadine was an amateur photographer before the war. The daughter of a Chinese ambassador to Spain, she moved to Paris in 1933 and joined Natalie Barney’s artistic circle. Barney openly lived and wrote as a lesbian, hosting a famous literary salon for decades inside her home at 20 rue Jacob.[6] Pictured on several occasions at the Parisian residence, Nadine made photo albums of Barney’s queer entourage in the thirties. These black and white snapshots survived the war, resurfacing decades later alongside the silent home movies from Caracas. Nadine, too, was a collector and curator animated, like Lifshitz, “by a desire to create the alternative histories and genealogies of queer lives” (Cvetkovich, “Photographing” 275).

Several years after he first identified her in the silent newsreel, Gertten resumed his archival encounter with Nadine, retrieving, this time, an unseen love story from the margins of the frame. On Christmas eve 1944, Nelly and Nadine met at Ravensbrück and became a couple. Nelly, a Belgian opera singer and member of the French resistance, was subsequently transferred to Mauthausen. She survived, also rescued by the Swedish Red Cross. Before the war, Nelly had separated from her husband, with whom she had two daughters. After the war, she reunited with Nadine. The two women lived together until Nadine’s death in 1972. When Nelly passed away in 1987, she left behind a trunk containing their domestic archive, which eventually passed down to her granddaughter Sylvie Bianchi.

A sexagenarian born during the Trente Glorieuses, Sylvie is the true protagonist of Nelly and Nadine. “My grandmother, she never talked about Nadine. Their meeting at Ravensbrück never came up in a conversation. As I recall, my mother did not like Nadine”, she explainsearly in the film, describing a family narrative not yet queer, still permeated with postwar silence. In the present day, Gerttencaptures Sylvie’s inability to see the two women as a couple, as well as the difficult process of unlearning the master narrative of the Trente Glorieuses. His dispositif is reminiscent of The Invisibles: the documentary is primarily set inside Sylvie’s home in northern France, where she lives with her husband, Christian. It is on this farm with a bourgeois interior that Sylvie resumes her encounter with Nelly and Nadine.

Upon opening her grandmother’s trunk for the first time, she detects an intimacy of survival beyond the realm of compulsory heterosexuality. She unexpectedly retrieves an alternative family archive comprised of both Nelly and Nadine’s belongings, including the prewar photo albums and the postwar Super-8 reels. “I do distinctly remember that Nadine always had cameras”, Sylvie remarks in the film. In a subsequent scene, she sits in her living room watching the home movies on her laptop. Now the same age as Nelly and Nadine in the colour footage, she belatedly witnesses their relationship through the eye of the amateur camera. Just as she notices their hands touching, the interior past spills into the present, queering the bourgeois family narrative: the same oval painting visible on the laptop screen now hangs on the wall behind Sylvie. In that moment, the juxtaposition between the two domesticities is salient. On their farm, Sylvie and Christian lead isolated lives that invoke a model of privacy associated with the postwar nuclear family. By contrast, the home images filled with dinners and friends recover an alternative kinship strategy, one in which the two women living in exile in the 1950s and 60s appear “connected to [others]—as, in many ways, dependent on for survival” (McRuer 96).

Another home movie titled “A Day in Caracas” epitomises the survivalist impulse of Nadine’s filmmaking. Resisting the master narrative of decline, which deprives aging women of their beauty and sexuality (Lindemann Nelson 89), the loving eye of the amateur filmmaker instead subverts familiar images of youthfulness to celebrate Nelly. In this ordinary and extraordinary home movie, Nadine chronicles their postwar everyday life: Nelly preparing breakfast; Nelly in the passenger seat of their Volkswagen Beetle, leaning out of the window to smile at the camera; Nelly and a friend swimming in the ocean; Nelly sitting at her desk at the French embassy where she worked; Nelly posing like a 1950s movie star with sunglasses and a headscarf, the coastal mountains behind her; Nelly dressed in a pretty green skirt while visiting a lush botanical garden with brightly coloured parrots. At the end of the reel, Nadine briefly appears on-screen, rendering their queer domesticity visible while claiming authorship frequently denied to women filmmakers (Zimmerman, “Introduction” 17).

In Nelly and Nadine, Sylvie emphasises her grandmother’s silence about her wartime experiences. In so doing, she echoes the pervasive belief that survivors did not want to speak about the trauma of the camps after the fact. In recent decades, scholars have countered this master narrative of silence with a wide array of early testimonies that exposed society’s reluctance to listen in the postwar period. Historical silencing also haunts the memory of Nazi violence against LGBTQ+ people, whose experiences were long excluded from the Holocaust narrative.[7] When Sylvie’s mother gave her Nelly’s trunk, she also transmitted the culture of silence of the Trente Glorieuses. On camera, Sylvie acknowledges that she has had the unpublished memoir in her possession for twenty years and has been unable to read it. When she finally does, she discovers more than just her grandmother’s love story. Inside the trunk, she finds a paper trail documenting the making of the manuscript, including journal entries on scraps of paper penned by Nelly inside the camps and a version of the memoir handwritten by Nadine in the postwar era. In encountering this part of their domestic archive, Sylvie finally understands that Nelly and Nadine wrote the memoir—together, mobilising a more generous and fluid vision of bearing witness in the face of social exclusion and historical loss.

The expression Trente Glorieuses is also never uttered in Gertten’s film. However, Nelly and Nadine harkens back to a homophobic postwar era that prompted the two survivors to leave France and Belgium for Venezuela, where Sylvie often visited her grandmother as a child. In the present day, the culture of silence and erasure that permeated the Trente Glorieuses resurfaces through clues: the figure of Sylvie’s mother who refused to stay in the couple’s home in Caracas; the social exclusion of Nadine, whose funeral Sylvie never attended in Brussels; a wartime memoir detailing their love story, which French publishers rejected; Nelly, who asks “What will become of us?” in the manuscript, seemingly referring to their survival both in the camps and after the war.

“So much of this kind of history is lost completely because, although people lived together, as your grandmother did, nobody says it. And nothing is real, socially, until it is expressed”, the late Joan Schenkar tells Sylvie in Nelly and Nadine. Schenkar was herself a collector and curator of queer archives: using “unknown, unread, and unpublished” writings, she penned a biography of Dorothy Wilde, Barney’s lover and Oscar Wilde’s niece (11). Early on in Gertten’s documentary, Schenkar and Sylvie peruse the photo albums belonging to Nadine. In this scene, they sit inside the Jacques Doucet Literary Library in Paris, which houses the paper archives of canonical French authors. This institutional setting focuses on the continued social marginalisation of Nelly and Nadine, whose unpublished memoir and unseen Super 8 films remained buried in a trunk long after the Trente Glorieuses.

The act of looking at snapshots of queer life inside the Parisian library intimates Gertten’s own reimagining of the archive in Nelly and Nadine. The documentary juxtaposes the black-and-white footage captured in Malmö in 1945 with the postwar home movies made by Nadine, thus endowing the amateur films—and the woman behind the camera—with archival significance and a sense of belonging. Like The Invisibles, Nelly and Nadine functions as a work of inclusion and an entry into representation. Both documentaries give a home to orphan images by moving them from the domestic archive to the public sphere, from the personal to the historical, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. “By creating larger spheres of collectivity”, Patricia Zimmerman remarks, “fractures of trauma are repaired” (“Introduction” 16). In our contemporary moment, Lifshitz and Gertten each create an archive of trauma and survival premised on reparative readings of the Trente Glorieuses.They confront missing pictures and stories, reassembling an intimate community of witnesses to transform cultural visibility and subvert the silence of the master narrative across generations.

Notes

[1] After The Invisibles, Lifshitz published in 2016 two more books from his collection of vernacular photographs: Amateur and Mauvais genre: les travestis à travers un siècle de photographie amateur. In the fall of 2019, he curated at the Centre Pompidou in Paris the exhibition L’inventaire infini, whose catalogue appeared under the same title. The sheer extent of Lifshitz’s archive calls to mind the important collection of snapshots associated with Casa Susanna, a 1960s resort for cross-dressers in the Catskills and the subject of an eponymous documentary he released in 2023. Casa Susanna includes many personal photographs that began to resurface in the early 2000s, offering a lesson in seeing how snapshots could provide shelter to and function as a place of belonging for a community of “invisibles” in postwar America (Hackett 205–06).

[2] As Lifshitz remarks in the book’s introduction, “As a teenager, when I dreamed of my adult life, if I stuck to the literature or the few films that existed on the subject, the future promised to be dark. To be gay or lesbian meant belonging to a genealogy of suffering, to have a dramatic, if not tragic, destiny. Despite the many battles and certain victories that ensued, the homosexual remained a victim in the collective consciousness; a hidden man” (par. 2).

[3] Christian’s trajectory finds an echo in the story of Pierre, the first protagonist (with his partner Yann) interviewed in The Invisibles. Closeted in his Catholic family, Pierre also escaped through travel: he spent a year in the South Pole for his military service, a chapter in his life that he documented with an amateur camera. With Thérèse and Christian, Pierre is the only other protagonist to have home movies in his possession.

[4] Only Thérèse’s grown children appear in The Invisibles. Themselves middle-aged, they call her by her first name rather than “mom”.

[5] Upon being interviewed by Gertten in Every Face Has a Name, Elsie Ragusin, the young woman standing to the right of Nadine in the newsreel, could not recall that a film crew had recorded them on that day.

[6] In The Invisibles, Thérèse omits the story of her paternal grandmother, Andréa Clerc, who accompanied the French writer Lucie Delarue-Mardrus to Barney’s salon in Paris. Little is known about her encounters within this famous literary circle that celebrated women writers and sexual freedom: when Andréa died in 1948, at the very beginning of the “Trente Glorieuses”, Thérèse’s father burned her diaries in an attempt to erase her queerness from the family narrative (Michel-Chich 41).

[7] On postwar silence, see Cesarini and Sundquist. On the historical erasure of queer victims and survivors, see Newsome.

References

1. Cesarini, David, and Eric J. Sundquist, editors. After the Holocaust: Challenging the Myth of Silence. Routledge, 2011.

2. Chareyron, Romain. “Sébastien Lifshitz: cinéaste des identités.” Modern & Contemporary France, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639489.2019.1586659.

3. Citron, Michelle. Home Movies and Other Necessary Fictions. U of Minnesota P, 1999.

4. Cvetkovich, Ann. “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice.” Feeling Photography, edited by Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu, Duke UP, 2014, pp. 273–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11319fq.17.

5. ——. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke UP, 2003.

6. Fourastié, Jean. Les trente glorieuses ou la révolution invisible de 1946 à 1975. Fayard, 1979.

7. Fuss, Diana. “Inside/Out.” Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, edited by Diana Fuss, Routledge, 1991, pp. 1–10.

8. Gertten, Magnus, director. Nelly & Nadine. Auto Images, 2022.

9. ——, director. Every Face Has a Name. Auto Images, 2015.

10. ——, director. Harbour of Hope. Auto Images, 2011.

11. Gullette, Margaret. Aged by Culture. The U of Chicago P, 2004.

12. Hackett, Sophie. “Bobbie in Context.” Imagining Everyday Life. Engagement with Vernacular Photography, edited by Tina M. Campt et al., Steidl, 2020, pp. 205–13.

13. Hallas, Roger. Reframing Bodies: AIDS, Bearing Witness, and the Queer Moving Archive. Duke UP, 2009. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jfm5.

14. Lifshitz, Sébastien. Amateur. Steidl, 2016.

15. ——, director. Casa Susanna. Arte, 2023.

16. ——. L’inventaire infini. Éditions du Centre Pompidou/Éditions Xavier Barral, 2019.

17. ——, director. The Invisibles. Peccadillo Pictures, 2012.

18. ——. The Invisibles: Vintage Portraits of Love and Pride. Translated by Molly Stevens, Rizzoli, 2014.

19. ——. Mauvais genre: les travestis à travers un siècle de photographie amateur. Éditions Textuel, 2016.

20. Lindemann Nelson, Hilde. “Stories of My Old Age.” Mother Time: Women, Aging, and Ethics, edited by Margaret Urban Walker, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999, pp. 75–95.

21. Martel, Frédéric. The Pink and the Black: Homosexuals in France since 1968. Translated by Jane Marie Todd, Stanford UP, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503617377.

22. McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory. Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. New York UP, 2006.23. Michel-Chich, Danielle. Thérèse Clerc, Antigone aux cheveux blancs. Éditions des femmes-Antoinette Fouque, 2007.

24. Newsome, W. Jake. Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Cornell UP, 2022. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9781501765155.001.0001.

25. Pessis, Céline, et al. “Introduction. Pour en finir avec les ‘Trente Glorieuses’.” Une autre histoire des “Trente Glorieuses”: modernisation, contestations et pollutions dans la France d’après-guerre,edited by Céline Pessis et al., Éditions La Découverte, 2015, pp. 5–31.

26. Radnor, Abigail. “Pictures of the Week: The Invisibles, by Sébastien Lifshitz.” The Guardian, 13 June 2014,www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2014/jun/13/invisibles-sebastien-lifshitz-gay-photography.

27. Schenkar, Joan. Truly Wilde: The Unsettling Story of Dolly Wilde, Oscar’s Unusual Niece. Basic Books, 2001.

28. Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction Is about You.” Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction, edited by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Duke UP, 1997, pp. 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822382478-001.

29. Spigel, Lynn. TV Snapshots: An Archive of Everyday Life. Duke UP, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478022893.

30. Wallace, Lee. “Queer Chattels and Fixtures: Photography and Materiality in the Homes of Frank Sargeson and Patrick White.” Domestic Imaginaries: Navigating the Home in Global Literary and Visual Cultures, edited by Bex Harper and Hollie Price, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66490-3_10.

31. Woodward, Kathleen. “Aging.” Keywords for Disability Studies, edited by Rachel Adams et al., New York UP, 2015, pp. 33–34.

32. Zimmerman, Patricia R. “Introduction. The Home Movie Movement: Excavations, Artifacts, Minings.” Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories, edited by Karen I. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmerman, U of California P, 2007, pp. 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520939684-004.

33. ——. “Morphing History into Histories: From Amateur Film to the Archive of the Future.” Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in Histories and Memories, edited by Karen I. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmerman, U of California P, 2007, pp. 275–88.

34. Zuromskis, Catherine. Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images. The MIT Press, 2013.

Suggested Citation

Cazenave, Jennifer. “Home as Survival: Seeing Queer Archival Lives.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 74–89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.05

Jennifer Cazenave is Assistant Professor of French and Film at Boston University. She has published articles, book chapters, and essays in such venues as Cinema Journal, SubStance, and Los Angeles Review of Books.Her monograph An Archive of the Catastrophe: The Unused Footage of Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah” (SUNY Press, 2019)received an honourable mention for the 2020 Best First Book Award presented by the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.