The Importance of a House and the Pandemic Formation of the ATLFilmParty Community

Jenny Gunn

[PDF]

Abstract

This article discusses the short films of the Atlanta-based black American filmmaker Olamma Oparah. Oparah’s film The Importance of a House was the winner of the inaugural ATLFilmParty (AFP) free film competition and industry networking event created by Brooke Sonenreich in the summer of 2021. Produced and directed in the era of both the COVID-19 pandemic and the aftermath of the US racial reckoning after the murder of George Floyd, The Importance of a House iterates the home as a site of refuge. This article analyses Oparah’s short in the context of two other films she directed in the same period, Laundry Day and No One Heals Without Dying that similarly explore the meaning of home as a black, female, and spiritual space. Using an object-oriented and artist-centered methodology informed by the author’s work with the liquid blackness research group, this article argues that Oparah’s films as texts speak to the contextual needs that AFP meets in fostering a local and independent home for filmmakers in Atlanta facing global Hollywood’s increasingly dominant presence in the city and the region.

Article

This article examines the birth of the ATLFilmParty (AFP) community in the spring of 2021, a collective and organically formed network of upcoming film practitioners and scholars working at the intersection of commercial and independent production in Atlanta, Georgia. More specifically, it examines the short film works of Olamma Oparah, who was the winning filmmaker of AFP’s inaugural open-call competition. Unlike when founder Brooke Sonenreich formed AFP in the spring of 2021, still prior to the wide accessibility of vaccinations, the majority of Americans were fully immersed in COVID-19 restricted work-from-home conditions that demanded the merging of the personal and the professional. The prior barrier between spaces, and a “room of one’s own”, particularly for working women, had both disappeared. As this article recounts through interviews with Oparah and Sonenreich, those conditions fully informed the DIY formation of the AFPcommunity, as well as the narrative themes of many of the submissions to its first short film competition, particularly the domestic and somatic themes of Oparah’s winning film, The Importance of a House (2021). The inspiration for both emerged within, and remain marked by, the imprint of the home’s private spaces yet speak to a persistent need for community despite the then still-strict isolation measures. The increasing presence of global Hollywood and mainstream streaming network productions in the metro-Atlanta area over the past decade have been equally determinative, driving the mission of AFPto foster a resistant, racially diverse, independently funded filmmaking collective of Atlanta-based filmmakers (Docktherman).

Atlanta is now a well-established location for production including tentpole films, TV series, indie films, animation, and reality series. According to the Georgia Department of Economic Development, as of 2022, more than 2,200 productions have been completed in the state of Georgia since 1972 (Tupper). Since 2008, the number of large-scale productions in the state has dramatically increased due to changes in the state’s tax incentives. As quoted in The Macon Newsroom,

according to the state, filming in Georgia provides a 20 percent base transferable tax credit, a 10 percent Georgia Entertainment Promotion uplift and both resident and non-resident workers’ payrolls qualify. Additionally, post-production of Georgia filmed movies and television projects qualify for these tax breaks if the post is done in Georgia. (Tupper)

Although these tax breaks are not without significant cost to the state, and thus not without controversy, their rationale is based on the economic impact they produce. By 2019, film and television was a 9.5-billion-dollar industry in the state of Georgia (Sandberg). The scale of the industry has fostered growth in the indie film scene and festival circuit in Atlanta as well. For example, Out on Film, one of only two Oscar-qualifying LGBTQ film festivals in the US and based in Atlanta, has seen its submissions double year-over-year as a result of the growth of the Georgia film industry (CBS46 News Staff). Nevertheless, it is still difficult for emerging Georgia-based filmmakers to find work in above-the-line roles in production. These are precisely the types of filmmakers that AFP aims to cultivate as a burgeoning community: day players in the industry, many of whom are graduates of Georgia university film programmes, with dreams of producing and financing their personal projects but who still lack the networking contacts and resources to succeed.

According to its website, AFP is a “a free, local, short form film competition and industry networking event with a goal of transforming ATL’s film industry into a real a$$ community that is accessible to all” (“A Little Bit”). Although filmmakers in Atlanta have access to established film screening competitions such as, most prestigiously, the Atlanta Film Festival, this is an international competition that includes full-length feature films and participation in these require significant fees. While the Atlanta Film Society, which runs the Atlanta Film festival, only charges modest fees for membership, its filmmaking community is very broad, from seasoned professionals to pre-professionals. Due to COVID-19, however, the operations of many large-scale film festivals in 2020 and 2021, such as Atlanta Film Festival, were impossible to safely maintain and were either cancelled or forced to go online. In this context, Sonenereich’s intention with AFPwas to foster a safe community of a manageable size where free-range socialising, if initially distanced and outdoors, was as crucial as formally screening films. It is in the centre of this intentionally social and local space that the potential for future DIY or low-budget collaborations is formed. AFP is thus only one of many case studies of what Marijke de Valck and Antoine Damiens have described as the “resourcefulness, adaptability, and creativity of festival organisers who had to, very quickly, find local solutions to a global calamity” (299). In the unique context of 2020 and 2021, the need for human interaction influenced festival and film competition participation as much as professional goals or prior experience.

This melding of the personal and the professional is at the roots of AFP’s beginnings. The formation of AFPstarted as the need for its founder Sonenreich to do something for herself, as she told me in an extended interview for this article. As a Jewish-American queer woman influenced by her parents’ dedication to the arts in her childhood home of Miami, Florida, Sonenreich was raised to believe that doing something for oneself is an inherently communitarian pursuit. Sonenreich works now as Events and Education Director at Moonshine Post-Production and was previously community relations manager for the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, another intentional filmmaking community in Atlanta, but AFP is her labour of love. At the time of its founding in the spring of 2021, Sonenreich was Editor-in-Chief at Oz magazine, an Atlanta-based business-to-business film and media industry publication. She worked on a regular series, “Filmmakers on the Rise”, dedicated to covering emerging Atlanta-based independent filmmakers. Drawing on this experience, Sonenreich decided in the spring of 2021 to launch the AFPfilmmaking competition that would invest in fostering the local Atlanta filmmaking community, intentionally bringing a diverse range of practitioners together in a shared space. But keeping her oral history a little more “real”, Sonenreich also revealed that, then in her late twenties, part of her impetus for starting AFP was to get over a recent break up. Indeed, both Sonenreich and Oparah, who had met previously in the Film and Media Master’s degree programme at Georgia State University, identified AFP’s beginnings in this break-up and the need for Sonenreich to “keep herself busy”.

Now in its third year, AFP waves all film submission fees for entry. Although the intention is for future calls to be limited to short films, a strict time limit was set in the first competition to encourage a large pool of entries. To make entering as easy as possible for contributors, the first call was for only two-minute experimental films. The submissions were then narrowed down and voted on independently by a jury of local film industry and academic professionals (including myself) to a group of four finalists to be screened and voted on by attendees at the first party in June of 2021. As mentioned, the winner of the first call was Olamma Oparah’s The Importance of a House. Despite the open-ended nature of the call for experimental films, The Importance of House was just one of several entries to the first competition cycle that emphasised domestic and somatic themes largely influenced by the pandemic conditions we were still then living under. For much of the general population in Georgia, the earliest COVID-19 vaccination appointments only became available in April, the same month as the first AFPcall. The organisers of the competition likewise asserted the theme of domesticity in the location they selected for the first party: Sleepy Housein Southwest Atlanta is a DIY gallery and home of the Atlanta-based painter Madison Sparks. COVID-19 continued to assert itself as well, with attendees mostly gathering outside and only cycling inside to watch the final four films in competition play on a loop as they cast their votes. Indeed, the pandemic haunted AFP throughout its entire first cycle (no pun intended—symptomatically, Cycle Two’s theme was “Horror”).

As a quarterly event, each call for films eerily coincided with another COVID wave—Alpha, Delta, Omicron. Mimicking the viral nature of COVID itself, each FilmPartydoubled in size from the one previous, leaving Sonenreich with an itinerant party in need of a permanent home once it had outgrown Sleepy House. Cycle Three (iPhone Shorts) was held at Underground Atlanta, a shopping and entertainment district in the Five Points neighbourhood of downtown Atlanta, and Cycle Four (Music Videos) at the beloved East Atlanta Village neighbourhood restaurant and bar, Argosy. By this time, sparkling water brand Topo Chico, Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer (PBR), and Videodrome, a local video store and Atlanta film scene institution, had all become sponsors. Burnaway, an Atlanta-based, non-profit magazine of contemporary art and criticism from the American South, had also begun carrying AFP’s calls for submissions. Despite this growing corporate and artworld support, Sonenreich was still preoccupied with the question of how to build a sustainable future for AFPand, more precisely, how to do so while continuing to prioritise the diversity of the film community it was attempting to cultivate. Save for Oparah’s initial win, competitors and attendees throughout 2021 were majority white. Beginning with the second cycle in the summer of 2022, Sonenreich intentionally pivoted, adopting a new strategy with new partnerships for season two and intentionally centring Black filmmakers that reflect the demographic uniqueness of the city of Atlanta compared to the film industry as a whole.

Figure 1 (left): Inaugural ATLFilmPartyposter advertisement sold at the event and shared on social media. Poster art by Brooke Sonenreich and Jordan Moore. Figure 2 (right): ATLFilmPartyposter advertisement for the second competition, Horror Shorts. Poster Art by Matthew Panuska.

To achieve this centring of Black practitioners, Sonenreich forged a partnership with Bianca Cato, a Black female Atlanta-based project manager in non-profit development. Cato had separately foundedAudio Video Club, a community screening film club held at the Cabbagetown neighbourhood bar, 97 Astoriaand Peters Street Station, a venue in Castleberry Hill, a historic neighbourhood and arts district adjacent to downtown Atlanta, frequently used as a film industry production location. Cato’s partnership helped AFP develop stronger ties within the Black independent filmmaking scene, and between FilmParty cycles, Sonenreich and Cato began partnering on smaller film-screening events as ATLFilmClub. The club’s March 2023 event was a screening of three of Oparah’s short films Importance of a House, Laundry Day (2019), and No One Heals without Dying (2022). Although Importance of a House was showcased at the “Best of Season One” in December 2022 at Switchyards Downtown club, the new permanent home of AFP, Sonenreich still felt compelled to host this event in honour of Oparah, partially because given its short two-minute length, the film was often missed by party attendees dropping in and out of the screening loop. Atlanta Journal Constitution arts reporter, Felicia Feaster, had praised all three of Oparah’s films as “the spiritual heart” of an exhibition entitled “Sweet/Discord” curated by the Black Women in Visual Artfounders, Lauren Jackson Harris and Daricia Mia DeMarrat, at Mint Gallery in the summer of 2021 (Feaster). At Mint, however, the films had screened on small installation screens, and Sonenreich wanted to showcase them in a theatrical full-size screening followed by a panel discussion featuring Oparah, which I moderated.

In its commitment to iterations of Black being and everyday life, the themes of The Importance of a House resonate with the spiritual heart of AFP. Specifically inspired by the Dikenga, or the African cosmogram, the film opens with a black screen with the sound of a teaspoon clinking against a glass. Next, we see shots of a domestic interior—den to dining room, cluttered work room, to cluttered kitchen sink overlaid with the following intertitles, which Oparah also reads aloud in voiceover:

In Igbo cosmology, the spirit moves in a circle, counter-clockwise from birth to adult rite. To death to becoming an ancestor and back to birth. So, the spirit moves in a way that each experience is longing for the next. The spirit wants to be housed in the body and the body is looking for relief from that house. It wants to be in the everlasting.

The symbolism of the Dikenga, as described in this opening voiceover, speaks powerfully to the conflicts of embodiment—to the spirit’s inherent ties to the body’s materiality but also the attenuated burdens of the body, whether racial, gendered, or more universally, its mortality, all of which then weighed heavily not only due to the pandemic but equally in the aftermath of the galvanising deaths in the US of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd by police, as well as the large-scale protests that followed.

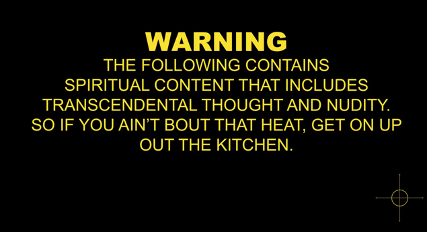

At the start of the film, we are “warned” by an intertitle of the African spiritual and nude content of the film (Fig. 3). In the short, which features thirty distinct shots in just two minutes,

Figure 3: Warning message that precedes the short film featuring the Dikenga symbol in the lower right corner. The Importance of a House (Olamma Oparah), Pot & Kettle Productions, 2021. Screenshot.

Oparah’s performance in the nude enacts the spirit’s restless relationship to the body. Like the pressure building up in the teapot we see placed on the stovetop and ignited in shot six, many shots feature Oparah’s restless movements around the house. Following the voiceover introduction, the remainder of the short film’s soundtrack features Paul Robeson’s original 1924 version of “All God’s Chillun Got Wings”. We first see Oparah, fully nude, engaging in domestic tasks such as picking up clothes or spraying down surfaces. Later, we see her resting or attempting to rest, but restless, unable to settle the body down comfortably onto the sofa. Instead, Oparah abandons the sofa, standing up to dance: first swaying her neck, then tapping her foot in two separate close-up shots. In montage with shots of Oparah’s readjusting on the couch, we are given the briefest flashes of an overgrown outdoor forest environment covered in kudzu, an invasive perennial vine commonly found in the Southeastern United States. These outdoor shots will return for longer stretches allegorising “the everlasting”, previously mentioned in her voiceover as we see Oparah’s nude dance performance occur here in greater length and with greater abandon. Although Oparah may physically be confined, dancing in the nude within her home, spiritually she is free as represented by the more expansive outdoor space of the nature preserve. Like the spirit’s conflicted interdependent relationship with the body in Igbo cosmology, the relationship of the metaphors in Oparah’s film are not purely oppositional; they guide her intimate directorial approach as driven by her spiritual beliefs.

Figure 4: Oparah’s nude performance in a Southwest Atlanta Nature Preserve, The Importance of a House. Pot & Kettle Productions, 2021. Screenshot.

Facing the increasing difficulties for independent filmmakers to access locations due to the dominance of Hollywood in metro Atlanta, Oparah’s home was certainly a convenient location to shoot during the pandemic, but her commitment to shooting films in her home runs much deeper. Oparah holds her home up as a safe space for women. More specifically, her home is an intentional site for a community of Black female filmmakers to freely experiment with their practice and pursue their vision unencumbered from white and male majority institutional settings such as academia and the industry (Oparah, Interview). This level of safety seems especially important for The Importance of a House given her identity as a Black female performing in the nude. But this film was certainly not without risk given its nude performance scenes on public property. Indeed, Oparah herself decided to perform the nude role in her film to avoid objectifying anyone else in the achievement of her vision. The intimate and domestic themes of The Importance of a House cross over with her short films, Laundry Day and No One Heals without Dying, shot during the same period.

Figure 5: Scene shot in Oparah’s home in Atlanta, Georgia, from Laundry Day (Olamma Oparah).

Sally Walker Productions, 2019. Screenshot.

Just over four minutes, Laundry Day also features Oparah’s voice-over narration duplicated as subtitles, and derived from the poem “Mother’s Stain” by Victoria P. Allen, who performs as the youngest daughter in the film. The themes of the poem regarding the inevitable but also difficult bond between mothers and daughters are reiterated in the film’s images, which shows three generations of Black women’s laundry routine. The grandmother still does her laundry by hand using a washboard, the mother uses a home machine, and the daughter does her laundry at the laundromat, conveying the greater precarity of youth. All three come together in the backyard of the mother’s home to hang laundry to dry on the clothesline. The film is dedicated to Toni Morrison and its soundtrack features Alice Coltrane’s “Angel of Air/Angel of Water” from 1974; Oparah and her cinematographer for all three films, Colbie Fray, often cut their films side-by-side while listening to Alice Coltrane. As expressed in the symbolism of the Dikenga cosmogram described in the voiceover of The Importance of a House, in Laundry Day Oparah revisits themes of the body’s conflicted relationship to the spirit: this time by examining the deep, generational ties of mothers and daughters through to the ancestors but also the pressures of labour in the everyday as crystallised through the mundane act of doing laundry.

Shanti Om, who plays the mother in Laundry Day, is the star of Oparah’s longest and most ambitious short film, No One Heals without Dying. With a runtime at just over thirteen minutes, No One Heals without Dying carries through the themes of Laundry Day,focusing on childbirth and the duties, risks, and rewards of Black motherhood. The film’s opening image in “Act I: Birth” is also the Dikenga, reiterating the cyclical and spiritual themes of The Importance of a House. Haunting, low-lit exterior shots of Om performing the active labour of childbirth, draped in a long red knitted skirt, are paired with the desynchronised sound of a policeman shouting hostile commands, which bleed over into cross-cut shots of found footage featuring police brutality and other forms of white-on-black violence. This sequence is followed by black-and-white footage of a live birth that they were able to add to the film when Fray’s sister went into labour during their production. “Act II: Death” returns to the earlier imagery of Om, still labouring before cutting to more experimental medium shots of her seated, her head being spooled with red thread, resembling the material of the knitted skirt she wears while labouring.

Figure 6: Actress, Shanti Om spooled in red thread. No One Heals without Dying (Olamma Oparah).

Pot & Kettle Productions, 2022. Screenshot.

Here the binding thread, like the length and heaviness of the knitted skirt, makes visible the non-negotiable burdens of motherhood, and particularly Black motherhood. Firstly, the fears of the Black mother for the safety of her child in a culture of white supremacy and state-sanctioned violence, secondly, the undue burdens on Black mothers as single parents. This reading is substantiated by the film’s next sequence of talking-head style interviews with Black women recalling either difficult romantic relationships or strained relationships with their fathers given their playboy reputations. The red lace background behind the subjects reiterates that of the blood-red thread, and the knitted skirt, as well as the blood-red colour of the Dikenga—as in The Importance of a House, here it appears once again—all underscore the cyclical nature of joy and pain that both love and family necessitate, which revolve around and emanate from the act of mothering. “Act III: Healing” features a sisterhood of women, dressed in Ghanaian funeral fabric used when someone young dies. In general, the red, black, and white colour scheme of the film is inspired by the Iyami Aje of Yoruba Cosmology, the divine mother, force of creation and sustainer of life. In Act III, the women, which Oparah conceptualises as seven priestesses, are seen journeying into the woods to perform a communal, healing ritual in the film’s first high-key daylit sequence. Oparah included this sequence in the third act because she felt that the film needed a release and wanted to show “the release that happens when women come together and grieve: that letting go, whether it be relationships, death, ego, can be very powerful and not something that I have ever seen shown of black women on film” (Oparah, Interview). “Act IV: Resurrection” features another talking-head style testimonial, this time of a daughter describing the guidance she was able to provide her mother in seeking out a mastectomy after a breast cancer diagnosis—the daughter’s strength helping her to step into her mother’s former place as family leader and reiterating the film’s emphasis on life’s cyclical nature. Optimistically, in the final sequence of the film, we see Om break free from the suffocating red thread that encases her. Her newly naked and smiling face is No One Heals without Dying’s final image.

As these brief descriptions of the narrative and style of Oparah’s films show, a certain anti-institutionalism reflects in the ethos of her practice, which is much more intuitive and organic. She rejects the conventions of the assembly-line production mode typical of traditional film and television industries, eschewing preproduction rituals such as storyboarding in favour of shooting the film in the same sequence as its narrative events occur to her. In fact, working with Fray, Oparah prefers to shoot first, visualising images first seen internally. The script emerges later from reviewing the footage and editing it in post. However, Oparah does pursue extensive meditation and open-ended research of her projects. For The Importance of a House, this process included coming upon the location for her exterior shots at the Kudzu-covered nature preserve in southwest Atlanta near her home that she happened to pass by at the golden hour. The discovery of this spot and the idyllic lighting at this hour inspired images in Oparah’s mind that ultimately led to the outdoor, nude performance segments of the film but also the inspiration for the interior shots in her home that focus on practices of keeping house:

It was a very organic process [. . .]. I did research. And I channelled. Meditated on it and I started getting images. So okay, I’m going to do this. I know I want to be in this space, and I drove around southwest Atlanta, and I found a space. You know, I was just driving to work one day, and I saw a nature preserve that was closed, and so I parked and went in there and it was unkempt and wild, and very scary. Because everything was really tight. There was a path, but it was way overgrown [. . .]. It was the golden hour and so I was like, this is where we’re going to shoot, and we’re going to shoot in my house. And I got these flashes of, you know, me doing domestic things, but the ritual of domesticity, the ritual of keeping your house. And the things that you have to do to clear out the energy because things can get cluttered and tight and that festers like depression. (Oparah, Interview)

I have placed the repeated word “tight” in italics in this quote to underscore how one shooting sequence organically informs the other in Oparah’s process. The overgrowth, unkemptness, and claustrophobia of the nature preserve’s kudzu-covered landscape returned her to the domestic labours necessary to clear the energy in the home, a theme that resonates not only with exacerbated COVID-era burdens of domestic and embodied cleanliness, but also histories of gendered and raced domestic labour. These histories, indeed, materially intervened in Oparah’s film, ultimately inspiring the title, The Importance of a House, when she coincidentally discovered a Home Economics textbook from the 1930s left in her house from a previous owner:

I was doing laundry, which is a part of my meditative practice, and I heard a whisper and that book called out to me, and I looked and there was this book among all my paint and tools that had been there. I guess I never cleared it out from the previous owner of the house. It was a home economics book from the 1930s, and it had all these lessons that they no longer teach, very sexist and racist. But also, a lot of really good practical information. It’s just the way that they thought about things like they didn’t know what melanin was. So, they were trying to explain why there are different skin tones because you have to dress according to your skin tone. Winter, Spring, Summer. And then you have to decorate your house according to your skin tone so that you can always appear beautiful to your husband. So, I saw the book, and I saw all the rituals, how to play with children, how to play with more than one child, how to hang pictures, you know, all of these things. It’s a thick book. It’s over 200 pages. And the drawings because there were no photographs. And I thought you know, homes are really important, and then as oftentimes when I’m making a film, the title comes first: The Importance of a House. And my body is a house because a lot of the book was about the body. So, The Importance of a House is really about the house as a home for the body, and the body as a home for the spirit. And the rituals that you do to maintain both. (Oparah, Interview)

The tension between housekeeping as an intuitive, even meditative practice that Olamma conveys in this anecdote and the regimented, disciplinary practices of both housekeeping and embodiment that the textbook preaches to women, contains echoes of Oparah’s frustrations with film as a discipline and industry. As previously stated, in her independent projects, Oparah does not work according to the regimented systemisation of industrial production modes. Indeed, her experience working in mainstream television production as an Executive Production Assistant on The Wonder Years reboot (2021–2023) only increased her distaste for the formalisation of the filmmaking process, despite the series being a majority Black production. Oparah found the systemisation of film and TV industrial productions as suffocating there as anywhere. Despite achievements in representation both behind and in front of the line that The Wonder Years represents, Oparah’s experience was that the form of the network family series remained dictated by the demands of whiteness and capitalism. The persistence of white supremacist forms echoes again in the selection of the soundtrack for The Importance of a House from Eugene O’Neill’s play All God’s Chillun Got Wings about a white woman’s resentful and abusive marriage to a Black lawyer, given her attachment to white supremacy and racial fetishism. This decision, too, arrived organically. Oparah had been reminded of a 1990’s Gospel choir rendition of the song while she was writing, but when discussing the emergent narrative and its inspiration in the vintage home economics manual with her frequent sounding board, her mother, she spontaneously mentioned being reminded of the Paul Robeson version of the same song, cementing Oparah’s decision to use this song as the film’s soundtrack.

In my interview with her, Oparah frames the intuitive nature of her process as opposed to traditional modes of production in philosophical terms, as the choice to value fluidity over rigidity as a mode of being. Embracing fluidity for Oparah required quite literally throwing out the rule book, rejecting further employment in the industry (despite its presence in Atlanta and the opportunities available) in productions where it remains attached to outdated systems and the assembly line mode. Instead, she admires contemporary Black filmmakers working across commercial and high-art contexts with newly fluid if challenging filmmaking practices such as Terence Nance, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, Jenn Nkiru, and perhaps the “godfather” to these all, Arthur Jafa. In the collective of the liquid blackness research group dedicated to the study of the contemporary Black arts based at Georgia State University, we have framed the practices of such filmmakers— with specific emphasis on this very fluidity as an aesthetic principle—as forging a new “music art video” practice, which leverages the experimental history of Black music from free jazz to hip-hop to inspire a new and experimental Black filmmaking aesthetic for the twenty-first century (“Music Video”). Jafa himself theorised the ethos of this new generation of filmmakers as “Black Visual Intonation” or the drive to materialise in contemporary Black filmmaking the boundary-breaking achievements of twentieth-century Black music. 267 Like these influential filmmakers, Oparah prefers to produce work in the short form and to showcase it in venues that bridge popular and fine art contexts centring blackness, precisely what Sonenreich’s AFPaims to provide for the Atlanta film community.

Framing contemporary Black moving image production as akin to a musical form— forged in collective and improvisational arrangements—liquid blackness prioritises new ways of approaching a singular work, privileging call-backs, citations, and riffs on other artists’ outputs. The methodology of liquid blackness is thus avowedly object-oriented (“What”). Theory emerges immanently from the artwork itself, which thus requires taking the creator seriously as not only an artistic but also an intellectual force. Thus, capturing the artist’s thoughts on their own works is a necessary requirement of the archival process. liquid blackness’ approach to crafting its research projects around its artists reflects this ethos, making plain the artist’s intentional network of relations to the creators that inspire them in film and other media. Prioritising interviews with Oparah, this method has been put into practice in this article. Let’s unpack just one of Oparah’s aesthetic lineages—break down merely one riff.

The domestic and feminist themes of Oparah’s films and her commitments to the local resonate with those of Baltimore-based filmmaker Elissa Blount Moorhead, whose work liquid blackness studied for the research project “Facing the Band: Elissa Blount Moorhead and the (Ana)Architectures of Community Ties”. Blount Moorhead’s films focus on “the poetics of quotidian Black life [. . .] emphasis[ing] quiet domesticity and community building.” The short title of the research project, “Facing the Band”, refers to Miles Davis’s tendency to turn away from his audiences in live performances in favour of facing his jazz ensemble. In her essay “Someday We’ll All Be Free”, Moorhead leverages this habit of Davis’s as a metaphor for her own ethical commitment to blackness (Moorhead). Similarly, Oparah has emphasised her commitment to centring blackness in both style and narrative but also as her intended audience—for both Moorhead and Oparah, as for Miles Davis, anyone else is only listening in. Both Moorhead and Oparah likewise prioritise creating conversations around their work—and facilitating a context for those conversations to occur—over commercial success or financial gain. This process of context facilitation, Moorhead understands as a unique mode of curation very close to the explicit goals of AFP. As the liquid blackness collective has argued in describing Moorhead’s practice, Oparah and Sonenreich likewise prioritise “forms of ‘curation’ that transcend their traditional sense and refer instead to a more careful gathering of people, communities, and ideas, around the making of art” (“Facing”).

Although Moorhead is not a filmmaker who Oparah mentioned in our conversations, direct exposure to an artist’s authored works is not necessary to prove in the hyper-contemporary climate of Black filmmaking today. As liquid blackness graduate research staffer Ashley Hendricks asks and answers in a recent promo reel for the tenth anniversary symposium of liquid blackness, “How do you make it legit? It’s already legit: all the [student] work that’s come out.” That is, in the digital video sharing online ecologies of YouTube and social networking, where artists today build followings, the mapping of influences is rhizomatic, not hierarchical. Recognisable artists are as likely to be influenced by their audience’s content as the inverse: the relationship is symbiotic, not didactic. Indeed, most of the filmmakers Oparah identifies as inspiring her practice have worked collaboratively. To take but one example, Moorhead is a partner in the production company TNEG along with Arthur Jafa and Malik Sayeed. For all of these players, social media and digital video sharing are crucial extensions of physical sites for facilitating such organic gathering and community-building between artists, scholars, and fans, particularly during the lockdowns of the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, Instagram remains an important promotional and networking site for both liquid blackness and AFP. Like Moorhead’s site-specific film As of a Now (2019), an x-ray projection screened onto the facade of abandoned Baltimore row houses that revivifies its former occupants’ presence through audio-visual recreations, the accumulating archive of the present documented through AFP’s film competition cycles similarly acts as a “repositor[y] of lived histories that urban renewal makes otherwise disappear” (“Facing”). Scholarship that flows from contemporary art objects is, in large part, inherently an archival process documenting individual threads of a filmmaking community in formation, constantly reforming as the networks of interaction among collaborators shift or become brittle in the face of material challenges to their survival.

To Atlanta independent filmmakers, the increasingly dominant presence of global Hollywood poses the most pressing gentrifying threat. As Oparah describes, the cost for independent filmmakers is rising because of the industry’s dominance on everything from locations to sets to crew fees. As a result, one of Sonenreich’s primary goals is to foster a community for crowd-sourcing production resources, not only creating a network of artists that can help to facilitate the achievements of each other’s projects but also securing donated film equipment for Atlanta-based filmmakers to utilise. While most of the AFPcompetitors ultimately seek the funding to make their own features, the shorts they produce for the competition provide the basis for securing the funding for more ambitious projects.

Having recently secured a substantial Creative Industries Grant from the City of Atlanta, Sonenreich also has ambitions to create a mentorship programme for local talent with industry leaders already present in Atlanta. Ultimately, AFPaims to entice the industry to have some stakes in the local talent in the Atlanta community and not just to fill low-level temporary day jobs. If minority filmmakers such as Oparah are understandably sceptical based on their experience in the industry, Sonenreich insists that for her, hope remains vital:

I think that there has to be a faith system. I personally, in order to keep doing this, have to have faith. That when the writing rooms come here, they’re not going to be lazy. They’re going to look for local talent and that might be a pipe dream, but for the first time, the Atlanta film office just came to ATLFilmClubto scout out what we’re doing. If Olamma was [featured] in the AJC (Atlanta Journal Constitution) because of a two-minute film that she made and because I had a breakup, then I just have so much faith in her vision and all the filmmakers’, but I mean especially my winning filmmakers’ visions that, they’re not going to be stagnant (Interview).

Unlike the Oscar-qualifying Atlanta Film Festival, the aims of AFPinherently must remain modest in scope to stay mission-focused on fostering local talent and building a local community. As Sonenreich describes echoing the themes of housekeeping that inspired The Importance of a House, this process is akin to tending to an ecosystem, to a form of mothering that requires a certain amount of emotional labour and, ultimately, a celebration of what this community has achieved in spite of the many barriers to entry at the time of its formation whether it be race, gender, economic precarity, or COVID-19: “There’s such a sterilized way of doing things in ordinary film festivals. Whereas I’m trying to emphasise that there are more letters in party than there are in film. It’s a joy thing.AFPis about preserving their joy in such a daunting sort of field” (Sonenreich, Interview).

Writing for the New Yorker on music videos shot by Arthur Jafa, journalist Cassie da Costa argues that historic lineages of Black aesthetics evolve with a great deal of opacity, but as I have argued in my work with the liquid blackness research group, it may be precisely where the proper terms of the lineage seem the least transparent that the work of the archive becomes most necessary (“Jenny Gunn’s Letter”). We may not know now exactly what the future of AFPwill hold or what its ultimate impact on the Atlanta filmmaking community will be, but it is without a doubt an important force in the genealogy of Black cinema to come. Given its intentional centring of Black independent filmmaking—its fostering of this community’s continuation in the face of industry dominance in the region, born in no less than a global health pandemic—the early history of the AFP community deserves documenting now before it becomes opaque. As two other committed “Atliens”, Big Boi and André 3000 of hip-hop duo Outkastremind us in their 2000 track “Humble Mumble”, “if you want to reach the nation, start from your corner.”

References

1. Allen, Victoria P. “Mother’s Stain.” Thoughts of a Mustard Seed, 2020.

2. CBS46 News Staff. “Indie Filmmakers, Festivals Benefiting from Georgia’s Thriving Film Industry.” Atlanta News First, 9 Aug. 2022, www.atlantanewsfirst.com/2022/08/09/indie-filmmakers-festivals-benefiting-georgias-thriving-film-industry.

3. Coltrane, Alice. “Angel of Air / Angel of Water.” Columbia Records, Sony Music Entertainment, YouTube, 26 Jan. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=sOlqlhF8dKU.

4. Costa, Cassie da. “The Profound Power of the New Solange Videos.” The New Yorker, 24 Oct. 2016, www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-profound-power-of-the-new-solan ge-videos.

5. Docktherman, Eliana. “How Georgia Became the Hollywood of the South.” Time, 26 July 2018. time.com/longform/hollywood-in-georgia.

6. “Facing the Band: Elissa Blount Moorhead and the (Ana)Architectures of Community Ties.” The Liquid Blackness Project, liquidblackness.com/elissa-blount-moorhead-research-project. Accessed 30 Mar. 2023.

7. Feaster, Felicia. “A Complex Mix of Pain and Joy Defines a Group of Contemplative Shows at Mint Gallery.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 17 Aug. 2021, www.ajc.com/things-to-do/a-complex-mix-of-pain-and-joy-defines-a-group-of-contemplative-shows-at-mint-gallery/M4UN37BQS5FWBNFSISX3MYAEXQ.

8. Gunn, Jenny. “Jenny Gunn’s Letter to the Editor: Re: ‘The Profound Power of The New Solange Videos,’ By Cassie Da Costa, New Yorker, October 24, 2016.” The Liquid Blackness Project, liquidblackness.com/curating-for-blackness/jgny. Accessed 30 Mar. 2023.

9. Jafa, Arthur. “Black Visual Intonation.” The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Columbia UP, 1998, pp. 264–68.

10. “A Little Bit About Us…” ATLFilmParty, 2023, atlfilmparty.com/about.

11. Moorhead, Elissa Blount. As of a Now. 2018. Light City, Baltimore, MD.

12. Moorhead, Elissa Blount, et al. “Someday We’ll All Be Free.” How We Fight White Supremacy: A Field Guide to Black Resistance, edited by Akiba Solomon and Kenrya Rankin, Bold Type Books, 2019, pp. 239–78.

13. “Music Video as Black Art.” The Liquid Blackness Project, liquidblackness.com/music-video-as-black-art. Accessed 30 Mar. 2023.

14. O’Neill, Eugene. All God’s Chillun Got Wings. American Mercury-Alfred A. Knopf, 1924.

15. Oparah, Olamma, director. The Importance of a House. Pot & Kettle Productions, 2021.

16. ——. Interview. Conducted by Jenny Gunn, 3 Feb. 2023.

17. ——, director. Laundry Day. PSally Walker Productions, 2019.

18. ——, director. No One Heals without Dying. Pot & Kettle Productions, 2022.

Outkast. Humble Mumble. YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zx3H99uPz_k.19. Patterson, Saladin K, creator. The Wonder Years. Lee Daniels Entertainment, 2021–2023.

20. Robeson, Paul. “All God’s Chillun Got Wings.” Ol’ Man River, Crates Digger Muisc Group, YouTube, 30 May 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=o-l-FL0acZQ.

21. Sandberg, Bryn. “States Race to Poach Georgia Film and TV Projects Amid Hollywood Boycott Calls.” The Hollywood Reporter, 4 June 2019, www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/states-race-poach-georgia-film-tv-projects-boycott-calls-1215532/.

22. Sonenreich, Brooke. Interview. Conducted by Jenny Gunn, 7 Feb. 2023.

23. Tupper, Sam. “Georgia and Macon’s Film Industry Continue to Grow despite Pandemic – The Macon Newsroom.” Macon Newsroom, 12 Dec. 2022, macon-newsroom.com/16025/studentwork/georgia-and-macons-film-industry-continue-to-grow-despite-pandemic.

24. Valck, Marijke de, and Antoine Damiens. “Film Festivals and the First Wave of COVID-19: Challenges, Opportunities, and Reflections on Festivals’ Relations to Crises.” NECSUS European Journal of Media Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 2020, pp. 299–302, necsus-ejms.org/film-festivals-and-the-first-wave-of-covid-19-challenges-opportunities-and-reflections-on-festivals-relations-to-crises.

25. “What Is Liquid Blackness?” The Liquid Blackness Project, liquidblackness.com/what-is-liquid-blackness. Accessed 6 Sept. 2023.

Suggested CitationGunn, Jenny. “The Importance of a House and the Pandemic Formation of the ATLFilmParty Community.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 154–168. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.10

Jenny Gunn is Assistant Professor of Film Theory in the School of Film, Media & Theatre at Georgia State University. Jenny is affiliated faculty with the liquid blackness research group, a collective at Georgia State University dedicated to open-access and collaborative study of the contemporary black arts.