Reproducing Home as a Space of Labour: The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai

Niyathi R. Krishna and P. Sivakumar

[PDF]

Abstract

In this article, we analyse home as a site of labour through two Indian films, The Great Indian Kitchen (Jeo Baby, 2021) and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai (Vipin Das, 2022). Produced and released in the Malayalam movie industry belonging to the South Indian State, Kerala, the two films received critical attention and generated broader discussion among Malayali audiences in the recent past. While the intricacies of gendered divisions of labour and domestic violence are documented through the day-to-day chronicles of the housewives’ lives in these films, we argue that both The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai illustrate how home is a different entity for men and women, conceptually and practically, as a space of leisure and labour respectively. Through narrative analysis, we interpret how these two films conceive and depict the disproportionate care work of women, highlight prevailing gender discrimination in a patriarchal setting, and expose new visual sensibilities to the audience.

Article

The COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide lockdowns have had a mixed impact on the medium of cinema in India. On the one hand, film productions halted midway and movie theatres closed in the wake of the first lockdown in 2020. On the other hand, subscribers of Over-the-Top (OTT) platforms increased, which led to films being produced exclusively for OTT release, an unprecedented practice in mainstream Indian cinema (Devaki and Babu 11307; Sunitha and Sudha 137). Even though the movie theatre experience was thoroughly missed by audiences, two significant changes were visible in Indian cinema during this period. First, most film shoots were limited to indoor locations with minimal cast and crews. This restriction eventually led to the creation of innovative and experimental films, web series, and documentaries and also motivated more women to get behind the camera. Second, the lockdown restrictions compelled many of these audiovisual narratives to highlight the home as the primary setting and theme, making the labour carried out within its walls visible.

The Malayalam cinema industry of Kerala, the southernmost state of India, is well known for its artistic content, innovative scripts, and veteran actors. It was also the first film industry in India to establish an organisation for women employed in the movies called Women in Cinema Collective (WCC) that “works towards building a safe, non-discriminatory and professional workspace for women in cinema through advocacy and policy change” (“Vision”). The past decade (2010–2020) has witnessed a higher number of women working in front of and behind the camera, and many mainstream films featuring a wide array of gender issues such as gender-based violence (domestic violence, marital rape, sexual violence, acid attacks, etc.), discrimination, stereotypes, and the gendered division of labour, which is notable given the extremely misogynistic context of the Malayalam film industry (Pillai, “Many Misogynies” 52). In 2020, COVID-19 lockdowns compelled people to stay at home. Many small-budget films in Malayalam on home and domesticity shot during this period have gained pan-Indian attention after their OTT release with subtitles, followed by awards and recognitions, and remake offers in other languages.

The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), directed by Jeo Baby, was one such film, released in January 2021 after many mainstream platforms refused to stream it since the content involved the political controversy regarding the Sabarimala temple (L. Jha). The Great Indian Kitchen portrays the gender politics of menstruation and pollution by incorporating the protests that happened in Kerala in 2018 against young women’s entry into the Sabarimala temple. A verdict of the Supreme Court of India in September 2018 allowed all Hindu pilgrims, regardless of their age and gender, entry to the temple, which was previously prohibited for women in their menstruating years (ten–fifty years of age). This verdict resulted in massive protests in Kerala, with many women in the forefront opposing the entry of women of reproductive age. This sensitive issue was boldly addressed in the film, which also problematises the gendered division of labour and women’s unequal burden of care work at home. Despite these controversies, the film received positive reviews and critical praise, was ultimately released on other mainstream platforms and was remade into two languages.

The Great Indian Kitchen narrates the journey of an aspiring dancer who is wedded into a prestigious traditional family with a substantial dowry. In her new marital home, she is confined to monotonous domestic tasks from dawn to dusk, devoid of any personal agency, and dominated by the family’s men. The narrative takes a pivotal turn when she is ostracised during her menstruation, leading to a sequence of distressing events that force her to reassess her self-worth. This introspection culminates in her decision to leave the marriage and pursue a life on her own terms. The Great Indian Kitchen has changed the way gender dynamics is narrated in movies (Pandey), and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai (2022), directed by Vipin Das and produced by Cheers Entertainments, is often called a “mass” version of The Great Indian Kitchen (Kumar). Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai was released in theatres in October 2022, and became a commercial success, followed by its OTT release in December 2022. Itdepicts the gendering process of a woman from childhood to adulthood and the tolerance of domestic violence in families (S. Jha; Nair; Vetticad; Dhar). Jaya (Darshana Rajendran), who has no means to escape domestic violence, starts resisting her husband Rajesh’s (Basil Joseph) physical abuse by learning martial arts online. Later, she is devastated to discover that she was deceived into becoming pregnant as a means to control her. This manipulation ultimately results in a miscarriage and her subsequent separation from her husband. Determined, Jaya establishes a business to rival her husband’s in the market. The film concludes showcasing Jaya as a content, divorced, and self-reliant individual. The gender politics represented in these two popular films shape home predominantly as a space of labour (Pandey; Pudipeddi; Shaji), and an ingrained workplace where women are expected to perform bonded labour based on love and loyalty.

Materials and Methods

We chose Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai and The Great Indian Kitchen for this study due to three reasons. First, although these are two widely discussed popular Malayalam films of 2021 and 2022 that unabashedly shifted the perception of the Indian family home as a love-driven, value-oriented, well-knit physical and emotional space, one was made for artistic purposes and the other purely for entertainment and theatrical experience. It is significant that films that are aimed at commercial success dare to discuss gender-related issues in the recent past in the context of Malayalam cinema. Second, these films traverse the binary of commercial movies and artistic movies (also called parallel movies) in the Indian context, in which the former are often defined as “feel good” and light entertainment, whereas the latter are conceived as classy, serious, and not intended to merely entertain. Third, men wrote, shot, and directed these two films, yet they highlighted significant gender issues within families through the portrayal of women. This is a positive step forward as male creators are addressing what is generally perceived as “women’s issues” as “gender concerns”, thereby making them mainstream.

While the intricacies of gendered divisions of labour and domestic violence are documented through the day-to-day chronicles of the housewives’ lives in these narratives, we argue that both films illustrate how home is an entirely different entity for men and women, both conceptually and practically. It is a space of rest and leisure for men and a site of labour for women. Through narrative analysis, we interpret how these two films have conceived and represented the disproportionate care work of women and highlighted prevailing gender discrimination within a patriarchal setting. Rather than providing a thorough examination of narrative structure, character and plot, our objective is to pivot the narrative analysis around three major themes that frame the plots of the two films, namely home and domesticity, home as a site of labour, and the status quo and the resistance of women. These themes are discussed in detail in the following sections.

The Representation of Home and Domesticity in Malayalam Films

Due to the patrilocal tradition prevalent in India, women have to leave their natal homes after marriage to settle down in their husbands’ homes, which often accommodate also their parents and siblings. We argue that, with the advent of globalisation in the early 1990s, Malayali women found that associated labour migration and the formation of nuclear families were an opportunity to escape the rigidity of traditional patriarchy and embrace modernity, for they could start a life of their own with as much agency as they could exercise within the scope of capitalist patriarchy. This is partly because of the fact that, while staying in the marital home, a woman had to adjust to the habits and practices of the marital family (and the customs and beliefs of the community) in terms of cooking, cleaning, and maintaining the household, and generally had to follow her mother-in-law’s instruction in performing her labour. In the nuclear family, however, she could independently engage in traditional roles, through some transformative advantages of modernity and negotiated levels of authority, even though she worked under the husband, the patriarch. This period also witnessed the transition of feudalist patriarchy to capitalist patriarchy, characterised, among other changes, by increased consumerism and mobility. The changing notions of masculinity in modern Kerala reshaped the modern husband to be somewhat progressive or a “liberal patriarch”, who allowed their fellow women to enjoy enough freedom.

As Pillai points out, “[r]egional cinemas in India have had a great role in imagining, shaping and embodying cultural and social identities as part of the project of modernity in India” (“Matriliny” 102). The representation of characterising aspects of this period in Malayalam cinema—i.e., unemployment of educated men, labour migration, disintegration of tharavadu (ancestral residence of upper-caste Keralites), and, eventually, the transition from the joint family (multigenerational family households) to the modern nuclear family during the 1980s and 90s—is accompanied by the lament of the traditional past, feudal nostalgia, resistance to modernisation, mocking of feminism, and the binary of rural/purity vs. urban/evil (Lukose 927). These changes (and their perceived dangers) were depicted through the transition of women and their alienation from tradition and culture that brought inevitable doom to the family (Menon; Pearson). Through women who make choices of their own over family sentiments, as in Alkoottathil Thaniye (I.V. Sasi, 1984), Vivaahithare Ithile (Balachandra Menon, 1986), Vatsalyam (Cochin Haneefa, 1993), and Pavithram (T. K. Rajeev Kumar, 1994), or women attracted to consumerism and modernity, as in Thalayinamantram (Sathyan Anthikad, 1990), Ayalathe Addeham (Rajasenan, 1992)and Sreekrishnapurathe Nakshathrathilakkam (Rajasenan, 1998), a large number of popular films during this time depicted in a negative light their female characters’ independence and the tiniest deviation from traditional gender roles. They reinforced the notion of the domesticity of women through the “morality” of the stories, showing that women with agency and who aspire to be independent have to pay heavy costs for disintegrating the family.

The trajectory of the representation of home in Malayalam films during the neoliberal period started in the early 1990s evoked sentiments of home or projected the traditional home as an element of nostalgia (Pillai, “Matriliny” 109). Therefore, women who embraced modernity were treated as antithetical to traditional nostalgia. The marital family in The Great Indian Kitchen, for instance,lives in the nostalgia of a feudal past and follows customs and practices that are rejected by modernity. During menstruation, the female protagonist, simply referred to as the “wife” (Nimisha Sajayan) has to remain isolated in a separate room without a bed and is restricted from touching anything in the household. The wife’s original family in fact takes pride in their alliance with such a traditional family. When the wife leaves the house (and marriage), her mother says to her, “Did you come out of the house for such a silly thing? Come, I’ll take you back. Apologise and go back to that house” (01:32:02). This not only indicates how women themselves are apathetic as well as indoctrinated to women’s disproportionate work burden and position in the family, but also internalise that, once married, a woman’s place is within the four walls of the husband’s household.

Ownership also matters when it comes to households. In Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, Jaya’s family lives in a rented house. When Rajesh’s family visits Jaya’s house to arrange the marriage, Rajesh’s mother asks: “Rented house? How do you sleep in a rented house?” (00:28:09). Later on, when Jaya undergoes a miscarriage, Rajesh’s mother comments, “We didn’t get anything from you”, hinting that Jaya’s family was supposed to provide a dowry, although Rajesh’s family didn’t demand it. She also indicates that the miscarriage is God’s punishment and tells Jaya that she should have thought about “God watching her actions” while she was disobedient and disrespectful to her husband. Witnessing these interactions, Jaya’s parents also blame her for her plight. In the following conversation, it becomes apparent that a married daughter can never go back to her original family:

Jaya to her mother-in-law: “I am not coming back home.”

Jaya’s mother (in anger and crying): “Then where else will you go?”

Jaya’s father (in anger with a raised voice): “We didn’t get you married for you to come out of it whenever you want. I won’t let you in to my house if you leave your marital home.”

Jaya: “Did I say I am coming there?”

Jaya’s mother (in anger): “Where else will you go?”

Jaya’s father (in anger with a raised voice): “Let her go. Let her. Then will you live alone? Do you have money? Do you have a job? Girls of your age are earning and living in a modest way. You are good for nothing.”(01:53:01)The film satirically depicts the hypocrisy of Jaya’s family, who made all the significant and insignificant decisions in her life without giving her any choice. They now accuse Jaya of facing the consequences of their own poor choices. At this point, Jaya realises that, though society dictates terms and conditions for a woman’s life, no one but the woman herself has to face the consequences. Both films not only capture the subtle and profound gender discrimination without compromise, they also demonstrate the points of women’s resistance without underplaying the fact that they still exist in a capitalist and patriarchal world. Within the home, neither resistance nor revolution truly liberates women unless it reshapes gendered spaces and challenges the gendered division of labour. In these two films, leaving home serves as the point of no return and the launching point of independence for the female characters. While The Great Indian Kitchen’s treatment of these turning points are very realistic, Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai celebrates and flaunts Jaya’s transformation, although toned down within the vulnerabilities and shortcomings of the character.

Home as a Site of Labour

Home has always been a site of labour in India, in terms of both economic and non-economic activities. Primary occupations such as agriculture, live-stock management, and home-based production were mostly centred in and around the home in the pre-colonised era. Both men and women were labourers in the household, even though the nature and gendered division of labour were distinct. With the advent of the capitalist economy, a shift to a stricter public–private divide occurred when economic labour was sought outside the domestic sphere. This led to a more rigid gendered division of labour, with men’s work seen as taking place outside the home and women’s work within it. The quantity of care work confined women to the home. Framed as a bondage of love, women were taught from childhood that it was their responsibility to take care of the family. This creates a moral dilemma for women since work performed out of love cannot be quantified or compensated.

The feudal system in the state considerably changed after the independence of India (1947), the unification and formation of the state of Kerala under the first communist government (1957), and ultimately with The Land Reform Act (1969). Several social reform movements that happened in Kerala during this period emphasised education and the cultivation of a scientific temperament among its populace. These initiatives also sought to empower women by freeing them from discriminatory customs and practices. Notably, The Great Indian Kitchen’s opening credits express gratitude to science rather than “God”. However, the invisible burden of domestic labour did not gain much consideration during these early development discourses.

Homes represented in Malayalam films are undoubtedly gendered. The movie camera has made gendered spaces and the gendered division of labour visible. The men sit in the living room or veranda, with a newspaper and/or a cup of tea, or talking to a guest in a leisurely manner, while women hurriedly run around the kitchen, alone or talking to someone while engaging in labour. Although the structure of houses changed from the old, tile-roofed Tharavadu or a traditional household—where joint families mostly lived—to concrete houses and apartments accommodating the nuclear family, the gendering of space and portrayal of the gendered division of labour in films remained unaltered, with very few exceptions in the past decade. This reinforced the association of home as a site of leisure for men and labour for women (Hochschild and Machung 4).

Home as a site of labour for women is synonymous with a capitalist workplace, but the reward at home is love as opposed to wages in the labour market. Hochschild rightly calls women’s unpaid care work as an act of outsourcing of the self. According to the “prisoner of love” theory (Folbre), this affective care work involves both material production and non-material reproduction at home and its extension outside. As Marxist feminism points out, women contribute to the political economy of a capitalist society in three significant ways: through the social reproduction of capitalism; as unpaid domestic labourers at home; and as reservoir of cheap labourers (Molyneux 8). Although Marx’s division of labour is not the context here, we argue that Marx’s alienation theory resonates with domestic labour as well, as women also get alienated from their activity, agency, and self. The means of production (home, people, and raw materials) are still owned by men and women workers are alienated from it.

Karl Marx defines alienation as “the breakdown of, the separation from, the natural interconnection between people and their productive activities, the produce, the fellow workers with whom they produce those things, and with what they are potentially capable of becoming” (qtd. in Ritzer and Stepnisky 26). Marx’s theory refers only to productive labour, and some scholars such as Alison Jaggar argued that housewives cannot be alienated (218, 307). However, Kain’s argument contradicts this. He notes that:

And just as alienation from the product and in the process of production gives rise to alienation from the species, because one does not control and therefore cannot direct either one’s product or one's activity for the benefit of the species, so also in housework and in child care, because the housewife does not control the product or her activity, she cannot direct them for the benefit of the species. Instead, housework and child care produce a mere commodity. They produce power. A woman works to prepare her children, her husband, and herself to enter the alienated realm of the factory; she thus works to distort and frustrate the development of the species.(131–32)

We argue that the alienation theory proposed by Marx becomes significant in these women’s plight. The women in The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai are restricted from having choice, compelled to work at their husband’s properties, unpaid and devalued, and denied any rewards, conditions that eventually alienate them from their labour, agency, and self. Unlike the capitalist, the husband gets an additional advantage of a dowry, along with an unpaid worker engaging in the social reproduction of his lineage. This alienation only applies to the activity and the space of labour. We also contend that the value attached to domestic work and the value attached to women form a vicious cycle of devaluation. The devaluation theory of care work argues that “care work is badly rewarded because care is associated with women, and often women of color” (England 381). While gendered division of labour allocates unpaid domestic work to women, which is unrecognised, unacknowledged, and undervalued, it gradually transforms into the identity (being) of women, which in turn devalues them.

The representation of women engaged in unpaid care work in films is also framed within the periphery of visual pleasure. It is primarily agreeable women (usually, the mother, wife, or sister of the male protagonist) in cleaning attire who are found engaging in domestic labour in popular movies. An overwhelming number of Malayalam films casted veteran actors such as Kaviyoor Ponnamma or K. P. A. C. Lalitha and Sukumari to play the “all-suffering mother” role (Ramachandran 118), often depicted draped in clean mundu neryathu (traditional attire of Kerala women similar to a sari), with a gracious smile selflessly working in the kitchen and caring for the family. However, the details of domestic labour are missing from the frame, since they are believed to add drudgery and monotony to the scene. Though some films represent culinary scenes with great detail (and the woman is out of focus), they only do that to stimulate the audience’s palate. This is where The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai diverge from typical films within the genre. First, they detail home, the activities being carried out at home and the person who carried out the activities. Second, women are portrayed beyond being gracious and visually appealing, instead they are depicted as sweating, bored, frustrated, angry, and aggressive while engaging in care work.

In Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, the process of gender indoctrination of the female protagonist (Jaya) was extremely discriminatory, and the family always reiterated that it is for her betterment (to be a marriageable woman in the market). While the family spent money on Jaya’s brother, they refused to do so to meet Jaya’s needs. She was asked to wear her brother’s used clothes, study from his old, torn textbooks, denied a tutor to pursue her favourite course, and finally her marriage alliance was made as though warding off a burden. In contrast, the wife in The Great Indian Kitchen wants to pursue a career but her father-in-law doesn’t want her to engage in wage labour (Shalini and Alamelu 703). He takes a benevolent sexist stance when he says, “It is grandeur to have women at home. What you women do is greater than what bureaucrats and ministers do” (01:04:16). In Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, Jaya was told before marriage that she could prepare for public examinations to gain formal employment after marriage; however, her husband refuses to let her study. These two circumstances reflect the reality and some of the major factors contributing to Kerala’s lower female labour force participation rate. Jaya’s education was always compromised by her parents as they only focused on her brother’s education. Because her husband is less educated, he doesn’t want her to study or pursue a career either.

In The Great Indian Kitchen, characters are intentionally left unnamed, and in Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai Jaya’s name is seldom mentioned. This is because her identity is largely defined by her father and husband. By choosing not to assign names, The Great Indian Kitchen encourages viewers to see these characters as reflections of their own personal and familial experiences. In Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, there is a particular flashback scene in which one of the female cashew workers labouring under the supervision of Jaya’s father asks him the name of his recently born girl child. Immediately another worker woman responds, “Why he needs a name for his daughter? He will call her Nee or Edee” (00:04:25). Everybody laughs as it is how he addresses them. “Nee” or “Edee” are phrases equivalent to “you” in meaning; they directly establish the hierarchy and authority of the speaker over the listener. Later on, it is obvious that Jaya is often called by these phrases rather than by name by her parents and husband. This is one of the examples of how women can be denied agency and autonomy, by constant othering from the self (Beauvoir 104). Consequently, the movie is titled Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai (meaning “Hail Jaya”, where Jaya indicates the name of the main character and also the literal meaning of the word “victory”), repeatedly emphasising her name to assert her agency.

The opening scenes of the film depict the early morning routines of a working class woman preparing food and rushing to the work place where she is treated very disrespectfully by the supervisor. Similarly, The Great Indian Kitchen starts with the contrasting, intercuts of the wife dancing and savouries being prepared at her home to receive the prospective groom. Once married, the wife in The Great Indian Kitchen has to work from early morning until late night and engage in sex almost on a daily basis, clearly without enthusiastic consent. The interior of the home is captured in longer single shots with a sound design that allows viewers to experience the space through the use of realistic sounds when the household is engaged in activities. Jaya also has to perform all the household activities and cook her husband’s favourite dishes amidst all the abuse. This reminds us of the fact that women’s time is spent on cooking and household work, resulting in the leisure gap and limited free time, which is very prevalent in India (Chakraborty 5). Also, both of these wives are very young, conditioned to obey elders, displaying timid body language, wearing a taali chain, sindoor (traditional attributes that indicate loyalty to husband), and salwar kameez, considered modest clothing for married women. They spend the majority of their time cooking and serving, often enduring insults. They tirelessly seek wage employment in hope of escaping this drudgery, while seemingly having no voice in their sexual and reproductive choices.

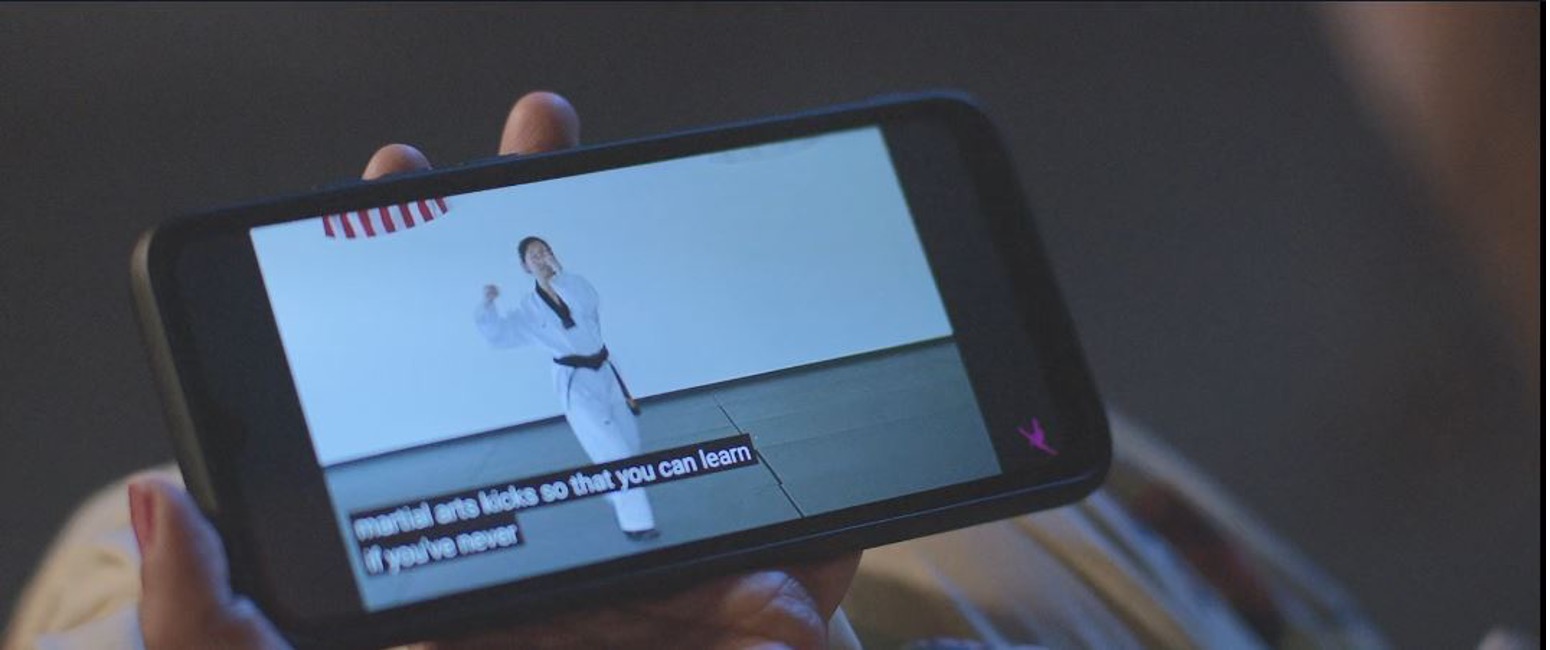

Furthermore, the father-in-law in The Great Indian Kitchen demands traditional cooking that takes more time and energy, and doesn’t allow women to use pressure cookers, mixers, grinders and washing machines. He is always seen leisurely sitting at home either reading a newspaper or watching YouTube videos. He is never seen entering the kitchen. Similarly, the husband (Suraj Venjaramood) doesn’t attempt to repair the leaking pipe in the kitchen sink that results in his wife manually cleaning it every time after use. The value dissociation of women is evident in these scenes and in two particular sequences that are thought-provoking due to their inherent paradoxes. In one specific scene from The Great Indian Kitchen, the wife drafts and sends a job application on her laptop while sitting in a traditional kitchen, surrounded by food being cooked on an open wood fire (Fig. 1). Another scene in Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai showcases Jaya learning Taekwondo using YouTube tutorials amidst her domestic duties (Fig. 2). These juxtapositions underline the irony: technology and progress have been introduced into these women’s lives, but they have not considerably alleviated the burdens of their domestic labour.

Figure 1 (above): The wife applying for a job using her laptop sitting at the traditional kitchen in the middle of cooking.

A frame that speaks of the contradictions. The Great Indian Kitchen, directed by Jeo Baby.

Mankind Cinemas, Symmetry Cinemas & Cinema Cooks, 2021. Screenshot.

Figure 2 (below): Jaya learning Taekwondo through YouTube. Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai,

directed by Vipin Das. Cheers Entertainments, 2022. Screenshot.

The theory of value dissociation (Scholz qtd. in Müller 3) suggests that, in a capitalist society, unpaid care work is separated from wage labour because it does not generate income. As this type of work is predominantly performed by women globally, both the unpaid tasks and the workers themselves are removed from the realm of recognised productive labour. Consequently, this separation leads to the diminished value of both care work and those who provide it.In both films’ representation of home, all the utensils, kitchen appliances and household appliances are old and outdated because men do not want to invest in them (Fig. 3). In Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, almost all the equipment in the house is broken indicating the violent behaviour of the husband. Cooking is entirely based on the demands of the husband and any cookery experiment or new additions on the menu are violently resisted by the husband (Fig. 4). Jaya undergoes passive and verbal aggression from her family of origin, controlling and physical abuse from her ex-boyfriend and a series of abuses from her husband (verbal aggression, slaps on the face, and manipulation). In contrast, the wife in The Great Indian Kitchen undergoes neglect and passive aggression where she is not allowed to exercise any agency.

Figure 3 (above): The wife engaged in daily cooking, unpleasant and tired.

This frame gives a snapshot of the kitchen. The Great Indian Kitchen. Screenshot.

Figure 4 (below): Jaya preparing Idiyappam, by pressing the dough through idiyappam maker,

a process that requires strength and energy. Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai. Screenshot.Not only gendered spaces but also the fact that these women do not have any ownership in the spaces they inhabit is also problematised in these movies. Both husbands in the movies make clear to the wives in various occasions that the house belongs to them, as in these examples from the dialogues of The Great Indian Kitchen: “My house, my comfort, and I will do whatever I wish to” (00:54:03) and “You have to obey us if you are living in this house” (01:26:29), or in the following ones from Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai: “You should be careful next time you talk to Rajesh” (00:38:48) and “You are done. Now you will live here obeying my orders and looking after my children. You will not go for a job or anywhere else. Now, didn’t you get to know who this Rajesh is?” (01:49:55). It is noteworthy that Jaya’s husband Rajesh uses his own name to stress a point and his house is named as “Raj Bhavan” (Rajesh’s house). He often tries to prove his masculinity and superiority over the household and among other family members. Both the wives are advised through various sources that their job is to satisfy their husbands and family members and work under their husbands in the households owned by them. In Jaya’s case, her husband doesn’t like Jaya lying down on the sofa watching YouTube videos. When the wife in The Great Indian Kitchen is deemed impure because of menstruation, everything she cooks, cleans, and tends to is promptly avoided by others. Her menstruation is treated with the same discrimination and ostracism as apartheid and untouchability. When the women complain to their own families about violence and discrimination, the parents (especially the mothers) normalise these experiences and behave indifferently to the women’s plight. Also, they try to convince their daughters repeatedly that they are privileged to have such a marital life.

Status Quo and Resistance

The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai are written, directed, and shot by men, yet the cameras captured women’s labour, discrimination, and violence faced by them and normalisation by the family. The films challenge common perceptions of family, which often serve as the stronghold of patriarchy and the main source of gender discrimination. In these settings, traditional gender roles are both perpetuated and strengthened. In these films, female characters are visually depicted as helpless, exploited, and transformed through domestic drudgery, abuse, and control. For example, Jaya’s initially frail physique transforms into one of strength and endurance. As she physically confronts her husband, her newfound vigour challenges the traditional notions of feminine passivity and helplessness. Women’s bodies are also desexualised and are depicted as a source of labour. For instance, in The Great Indian Kitchen, a sex scene portrays the wife with a look of revulsion, her mind preoccupied by the odour of discarded food.

The wife in The Great Indian Kitchen realises that while menstruating she is treated as dirty and disgusting as the food waste oozing out through the leaking pipe in the kitchen. She observes that even their housemaid possesses greater social mobility, and her menstrual cycle is overlooked by the family when observing traditions that isolate menstruating women. It becomes apparent that the wife’s menstruating body becomes as disgusting to the husband as the food waste; both are by-products of her husband’s pleasure. She defiantly hurls the dirty water of the food waste, the residue of her labour’s efforts, at her husband and father-in-law, then locks them in the kitchen. She also chooses to come out of the house through the front door, walking past the visitors sitting in the veranda, indicating that she is neither guilty of her action nor cares what people may think of her behaviour. She divests herself of all the patriarchal symbols of loyalty that she carried on her body—her taali chain, sindoor, etc.—and embraces the world bravely. The same confidence is visible when Jaya leaves the court room after signing the divorce petition. The transformation from meekness to confidence is due to the fact that they have made a decision for themselves and they are unapologetic about the consequences (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

Figure 5 (above): The “divorced” wife on her way to the stage to choreograph a dance performance.

The Great Indian Kitchen. Screenshot.

Figure 6 (below): The “divorced” Jaya leaving the courtroom. Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai. Screenshot.

In The Great Indian Kitchen, the linear narrative and realistic and slow-moving scenes immerse spectators so convincingly that they feel they are personally experiencing the detailed and slow-moving scenes depicting the drudgery of domestic labour.However, Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai has a non-linear, sensationalistic structure that provides entertainment value through the use of music, background score, number of frames, and frame speed. Another compelling aspect of the visual narrative/aesthetics is the consistent presence of metaphors such as food waste in The Great Indian Kitchen and cashew nut in Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai. While food waste indicates the invisible unpaid domestic labour and the objectification of the labourer woman, the cashew nut may be seen to signify the phallus representing patriarchy. During the transformative fight in the movie, the shot of burned hard cashew nut shell being smashed is used in intercuts between the fight, indicating Jaya’s resistance to patriarchy.

For both women, leaving home represents a point of no return. Even though they are trying to transform and resist subjugation within the household, they are isolated in the process within the structure of a patriarchal family. Despite being cordial, supportive, and caring towards the family members, family as a system supports the men, rather than these women, who are struggling. The movies do not portray male characters as evil, cruel and vicious in their interactions with the outside world, but instead, they are portrayed as regular family men the audience can relate to. This relative perspective and suspension of disbelief challenge the male gaze, especially when characters’ aggressions are criticised instead of being lauded as masculine traits. At the same time, home also becomes the point of self-realisation for these women. The wife in The Great Indian Kitchen is seen with a laptop filling in the application form for a job, while Jaya uses the internet as an opportunity to learn what was previously denied to her. When women attempt to voice their concerns, their husbands’ delicate egos are bruised, making them unwilling to question their patriarchal privileges. Jaya, who inhabits the marital house in constant fear and threat of being beaten, ultimately retaliates physically against her husband’s violence. She hits, kicks, and punches him when he attempts to beat her. Soon, she prepares for a reconciliation, but departs from the marital home upon realising she was deceitfully impregnated to ensure her lifelong subjugation.

We contend that these women’s desire for an individual identity was pivotal to their transformation. Both women confronted their husbands’ dominance, both within the household and externally, ultimately departing from their marital lives forever. Both achieve economic independence: Jaya emerges as an entrepreneur competing against her husband’s business, while the other woman becomes a dance school teacher. In a significant move, she takes charge of the car—initially given as a dowry to her husband—and, in doing so, reclaims control over her life. While she may have escaped the confines of the kitchen, however, another woman soon steps in to take her place, inheriting the same responsibilities. This underscores the notion that, while individual female protagonists may escape their predicaments, the overarching system remains unchanged.

Conclusion

At the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, increased domestic violence and women’s unequal burden of care work were widely addressed as serious concerns (UN Women, “Shadow Pandemic”; “Whose”). Globally, people were confined to their homes, and outsourced care work, like many other forms of paid labour, came to a halt. Interestingly, many attributed this to men being limited in their movements and obliged to stay home—a restriction women have faced for centuries. Domestic violence was labelled a “shadow pandemic,” and the issue of women’s time poverty, combined with a care crisis (Fraser 117), became a focal point in academic research and policy discussions worldwide. At this point, The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai, which represent these gendered labour concerns, were introduced to the general public within a traditional patriarchal setting.

We conclude this essay by reiterating the three major themes articulated in these films. First, the movies portrayed master–slave (Beauvoir 19) or capitalist–worker relationships between husband and wife, which are reproduced at home and perpetuated through gendered divisions of labour, social norms, and customary practices. For a country like India, it is still the status quo. This challenging dynamic is perpetuated through the gender roles assigned to women, their bodily expressions, activities, and domestic responsibilities. Second, while women can resist, their ability to do so is constrained. Even though these women transform and start resisting exploitation within the home, it is when they leave the (marital/husband’s) home forever that they are able to exercise agency in their life and claim their individuality in terms of autonomy and vocation. We must remember that, as they transition from the marital home to the workplace, their exploitation shifts from a patriarchal household to a capitalist work environment. However, this capitalist paid labour gives them economic independence, social status, and social mobility. Also, it is observed that the home and men withstand this change. Finally, it is noteworthy that, in these two films, women seize the narrative spotlight as protagonists, thereby becoming central subjects, contrary to the earlier movies that depict a woman’s world limited to the home and domestic tasks through a male perspective. The depiction of their actions and experiences bring depth to the scenes. We argue that this introduces fresh visual perspectives to the viewers.

2. Taali is a heart-shaped pendant on a gold chain that the groom ties around the neck of the bride during the wedding of Kerala Hindus. This indicates that they are married. After that, he puts sindoor (vermillion) on the parting of the hair above her forehead. This indicates a long marriage. An ideal Hindu wife is supposed to be seen wearing both as long as she is married.

References

1. Alkoottathil Thaniye. Directed by I.V. Sasi, Century Films, 1984.

2. Ayalathe Addeham. Directed by Rajasenan, Kairali Films Productions, 1992.

3. Chakraborty, Lekha. “Covid19 and Unpaid Care Economy: Evidence on Fiscal Policy and Time Allocation in India.” NIPFP Working Paper Series, No. 372, 28 Feb. 2022, www.nipfp.org.in/publications/working-papers/1971.

4. Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated and edited by H. M. Paishley, London, Routledge, 1962.

5. Devaki, Revati, and Dinesh Babu. “The Future of Over-The-Top Platforms after Covid-19 Pandemic.” Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, vol. 25, no. 6, 2021, pp. 11307–13.

6. Devika, J. “The Defence of Aachaaram, Femininity, and Neo-Savarna Power in Kerala.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, 2020, pp. 445–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521520939283.

7. Dhar, Debabratee. “Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey: An Escapist Fantasy for Women, a Warning for the Rest.” Film Companion, 9 Jan. 2023, www.filmcompanion.in/readers-articles/jaya-jaya-jaya-jaya-hey-an-escapist-fantasy-for-women-a-warning-for-the-rest.

8. Engels, Frederick. “The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State.” Translated by Alick West, Marx/Engels Selected Works: Volume 3. International Publishers, 1942.

9. England, Paula. “Emerging Theories of Care Work.” Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 31, 2005, pp. 381–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122317.

10. Folbre, Nancy. The Invisible Heart: Economics and Family Values. New Press, 2001.

11. Fraser, Nancy. “Contradiction of Capital and Care.” New Left Review, vol. 100, 2016, pp. 99-117.

12. The Great Indian Kitchen. Directed by Jeo Baby, Mankind Cinemas, Symmetry Cinemas & Cinema Cooks, 2021.

13. Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. Penguin, 2012.

14. Jaggar, Alison M. Feminist Politics and Human Nature. Rowman & Littlefield, 1983.

15. Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai. Directed by Vipin Das, Cheers Entertainments, 2022.

16. Jha, Lata. “Tamil Remake of The Great Indian Kitchen to Release on 29 December.” Live Mint, 24 Dec. 2022. www.livemint.com/industry/media/tamil-remake-of-the-great-indian-kitchen-to-release-on-29-december-11671857089287.html.

17. Jha, Subhash K. “Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey: A Bubbling Satire on Gender Stereotypes That Loses its Fizz.” First Post, 17 Jan.023. www.firstpost.com/entertainment/jaya-jaya-jaya-jaya-hey-a-bubbling-satire-on-gender-stereotypes-that-loses-its-fizz-11997682.html.

18. Kain, Philip J. “Marx, Housework, and Alienation.” Hypatia, vol. 8, no. 1, 1993, pp. 121–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1993.tb00631.x.

19. Kumar, Manoj R. “Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey: The ‘Massy’ Version of The Great Indian Kitchen.” Indian Express, 27 Dec. 2022. indianexpress.com/article/entertainment/jaya-jaya-jaya-jaya-hey-the-massy-version-of-the-great-indian-kitchen-8345323.

20. Lukose, Ritty. “Consuming Globalization: Youth and Gender in Kerala, India.” Journal of Social History, vol. 38, no. 4, 2005, pp. 915–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2005.0068.

21. Menon, Neelima. “Malayalam Cinema’s History of Slotting Women Into the Good-Bad Binary.” The News Minute, 19 July 2023. www.thenewsminute.com/kerala/malayalam-cinema-s-history-slotting-women-good-bad-binary-179947.

22. Molyneux, Maxine. “Beyond the Domestic Labour Debate.” New Left Review, vol. 116, no. 3, 1979, pp. 3–27.

23. Müller, Beatrice. “The Careless Society: Dependency and Care Work in Capitalist Societies.” Frontiers in Sociology, vol. 3, 2019, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2018.00044.

24. Nair, Ranjini. “Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey: How a Movie About Domestic Violence Reveals the Patriarchal Biases We Have as an Audience.” Indian Express, 19 Jan. 2023. indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/jaya-jaya-jaya-jaya-hey-domestic-violence-darshana-malayalam-movie-8383326.

25. Pandey, Geeta. “The Great Indian Kitchen: Serving an Unsavoury Tale of Sexism in Home.” BBC News, 11 Feb. 2021, www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-55919305.

26. Pavithram. Directed by T. K. Rajeev Kumar, Vishudhi Films, 1994.

27. Pearson, Edna. “Malayalam Cinema and ‘Her’ Evolution.” The Times of India Readers’ Blog, 21 Mar. 2023. timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/indianwaysofportrayingromeosandjuliets/malayalam-cinema-and-her-evolution-51728.

28. Pillai, Meena T. “The Many Misogynies of Malayalam Cinema.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 52, no. 33, 2017, pp. 52–58.

29. ––––. “Matriliny to Masculinity: Performing Modernity and Gender in Malayalam Cinema.” Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas. Routledge, 2013, pp. 102–14.

30. Pudipeddi, Haricharan. “The Great Indian Kitchen Review: Powerful Film on Patriarchy and Men-Governed Traditions.” Hindustan Times, 16 Jan. 2021. www.hindustantimes.com/entertainment/the-great-indian-kitchen-review-powerful-film-on-patriarchy-101610792874537.html.

31. Ramachandran, T. K. “Note on the Making of Feminine Identity in Contemporary Kerala Society.” Social Scientist, vol. 23, no. 1–3, 1995, pp. 109–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3517894.

32. Ritzer, George, and Jeffrey Stepnisky. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots: The Basics. Sage Publications, 2022.

33. Shalini, Lourdes Antoinette, and C. Alamelu. “The Great Indian Kitchen: Serving of an Unpalatable Tale of Male Chauvinism in Home.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 12, no. 4, 2022, pp. 702–06. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1204.10.

34. Shaji, Sukanya. “From Veruthe Oru Bharya to The Great Indian Kitchen: Female Identity in the Domestic Space.” Feminism in India, 18 Oct. 2021, feminisminindia.com/2021/10/18/great-indian-kitchen-kerala-state-awards-jeo-baby-nimisha-sajayan.

35. Sreekrishnapurathe Nakshathrathilakkam. Directed by Rajasenan, Highness Arts, 1998.

36. Sunitha, S., and S. Sudha. “Covid-19 conclusion: A Media and Entertainment Sector Perspective in India.” Vichar Manthan, vol. 8, no. 24, 2020, pp. 135–37.

37. Thalayanamantram. Directed by Sathyan Anthikad, Mudra Arts, 1990.

38. UN Women. “The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women During COVID-19, 2020.” www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19.

39. ——. “Whose Time to Care? Unpaid Care and Domestic Work during COVID-19, 2020.” data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Whose-time-to-care-brief_0.pdf.

40. Vatsalyam. Directed by Cochin Haneefa, Jubilee Productions, 1993.

41. Vetticad, Anna M. M. “Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey Movie Review: Domestic Abuse Satire that Seesaws from Realism to Myth, Depth to Superficiality.” First Post, 22 Nov. 2022. www.firstpost.com/entertainment/jaya-jaya-jaya-jaya-hey-movie-review-domestic-abuse-satire-that-seesaws-from-realism-to-myth-depth-to-superficiality-11674081.html.

42. “Vision & Mission.” Women in Cinema Collective, wccollective.org/about. Accessed 20 Jan. 2023.

43. Vivaahithare Ithile. Directed by Balachandra Menon, V&V Productions, 1986.

Suggested Citation

Krishna, Niyathi R., and P. Sivakumar. “Reproducing Home as a Space of Labour: The Great Indian Kitchen and Jaya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hai.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 58–73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.04

Niyathi R. Krishna, PhD, is assistant professor at Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development (RGNIYD), India and has around ten years of academic experience in qualitative research. Her areas of research interests include Gender, Migration, and Labour. She is the recipient of Sir Ratan Tata Post-Doctoral Visiting Fellowship (2023–24) at the London School of Economics and Political Science, UK. In 2020, she was awarded the first Triennial “Preet Rustagi Research Fund Award” by Indian Association for Women’s Studies (IAWS). She has published two collections of poems and is a film enthusiast. She is also the recipient of National Balshree award from the President of India for excellence in Creative Writing.

P. Sivakumar, PhD, is an academic and development practitioner who has been working in the area of youth development for almost two decades. He is currently the Head of the Department of Development Studies at Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development (RGNIYD), India. His areas of research include migration, labour, and social policy. He is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in Development Ethics (Indian Council of Philosophical Research Fellowship) from Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi. He has been associated with UNICEF; UNV; UNESCO-MGIEP; Commonwealth Youth Programme (CYP) London; and Centre for Development Studies (CDS), Kerala for various projects. His latest works include Sustainable Development Goals and Migration (Routledge, 2021) and Tamil Migrants: Demographic, Social and Economic Analysis (Orient Blackswan, 2021).