Home Movies as Technologies of Belonging and Resistance

Elizabeth Patton

[PDF]

Abstract

This article examines the significance of home movies as tools of resistance and belonging, particularly for African American families during the Civil Rights era. Focusing on archival collections from the South Side Home Movie Project (SSHMP), African American Home Movie Archive (AAHMA), and the National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), the study reveals how African American families, through their cinematic documentation of visits to national parks and other leisure activities, challenged prevailing narratives of national identity. Despite encountering rampant discrimination, these families captured moments of joy and relaxation, highlighting their resilience and assertion of their rightful place within the American narrative. These historical home movies are profound testimonials of Black identity, resilience, and belonging in the face of adversity. Examining these films enriches our understanding of cultural memory, national identity, and the role of African American home movies in presenting a more nuanced American history.

Article

The screen brightens with the warm, grainy hues of Super 8 mm footage. Two bucks appear, grazing in a quiet clearing. Amidst the dense thicket of trees and tangled underbrush, the camera observes them, unseen and undisturbed. Their ears twitch, and tails flick occasionally, but they remain engrossed in their meal, providing an intimate glimpse into nature. A swift cut transports us to a breathtaking mountain vista. But this expansive view is interrupted abruptly. The camera jostles slightly before it settles onto a wooden plaque mounted to what appears to be a large rock on the ground. The engraved words reveal our location: “Pulpit Terraces”. A momentary pause occurs as the importance of the terraces is hinted at before the scene shifts again. Returning to the grandness of the mountain range, the camera initiates a slow, deliberate pan from left to right. The movement is smooth, contrasting with the earlier shakiness, guiding our eyes across the vast landscape, inviting us to breathe in the pristine air and immerse ourselves in the Patton family’s journey through Yellowstone National Park.

The Jean Patton Collection, accessible at the South Side Home Movie Project’s (SSHMP) website, captured by Chicagoan Jean Patton and her spouse Robert, chronicles their family life as well as their numerous vacations. With over one hundred reels, the collection features various film formats, including 16mm, 8mm, and Super 8 mm, from the 1940s to the 70s. The compilation of vacation titles offers a glimpse into the Patton family’s adventures: from Yellowstone National Park, the Tetons, Cheyenne to Denver, Colorado. As the couple ventured through Yellowstone National Park and the Grand Tetons in 1966, their home movies captured breathtaking landscapes with a level of expertise and intentionality that elevated them beyond the average family film. Utilising various filming techniques, such as panning, highlight the couple’s ability to create a narrative through their travels.

Figure 1: “Title cards.” Vacation (1966) Titles. 1966, 8 mm colour film. Jean Patton Collection.

South Side Home Movie Project, University of Chicago.

The Patton home movies also display remarkable attention to detail and forethought in documenting the family’s experiences, as demonstrated by the title cards they created for their films. These do-it-yourself title cards, created on Super 8 mm film, feature cut-out letters pasted onto picturesque backgrounds of lakes and mountains (Fig. 1). The Patton home movies’ meticulousness, as evidenced by their customised title cards and filming techniques, provides insights into their film practice. The deliberate use of title cards demonstrates a high level of commitment and investment in their filming. It reveals that they approached filmmaking with a semi-professional or at least very dedicated attitude, valuing documentation and presentation. The DIY nature of the title cards, with cut-out letters set against captivating backgrounds, also offers a window into the couple’s creative spirit and collaborative efforts. Creating these films probably became a cherished family activity, fostering bonding and a collective memory-making process. Overall, this level of dedication in documenting their travels demonstrates their belief in the importance of preserving and sharing the tourism experiences of African Americans.At a time when dominant public narratives were saturated with overt forms of political action, such as protests and sit-ins or mainstream African American cultural performances, these personal cinematic records offer a crucial counter-narrative. These home movies act as repositories of cultural memory, preserving the complexity and contradictions of Black life. African American home movies, particularly those capturing leisure activities in places like national parks, do more than document familial moments—they become subversive tools in shaping perceptions of national identity and belonging during tumultuous times. The act of leisure, especially during the Civil Rights era, takes on a revolutionary dimension for Black Americans. Leisure, after all, is often a privilege—one that was systemically denied to African Americans through both legal, economic, and social means. These Black families were silently staking their claim to the national narrative by documenting their presence in national parks, a symbol of American identity. Their very presence in these parks can be read as a refusal to be confined to the peripheries of the American dream.

In my pursuit to examine the less-documented facets of African American leisure activities, I explored three pivotal archival collections of home movies. Spanning from the 1920s to the 80s, the South Side Home Movie Project (SSHMP), initiated by Dr. Jacqueline Stewart at the University of Chicago, curates and preserves films made by individuals residing in historically African American neighbourhoods in Chicago’s South Side. Established in mid-2014 by Jasmyn R. Castro, the African American Home Movie Archive (AAHMA) features the Black Home Movie Index, which includes African American home movie collections from the early 1920s to the mid-80s. Its primary goal is to promote access, research, and reuse of these films, contributing to a more diverse understanding of the African American community. Rounding off my sources is the National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), which has diligently safeguarded a vast collection of African American home movies. These films recontextualise Black moving image history and offer insights into the multifaceted narratives of African American heritage. My decision to explore these archives was driven by their rarity, given the limited circulation and accessibility of most African American home movies. Notably, while many films showcased middle-class African American vacations to beaches, resorts, or family visits, I was intrigued to discover a significant number that documented visits to state and national parks.[1]

In this article, I examine the intersecting narratives of national parks as sites of American identity and home movies as technologies of belonging and resistance. Through these cinematic archives, African American families, venturing into spaces of national identity like national parks, challenged and reshaped notions of belonging, asserting both their right to joy and their undeniable place within the American narrative. The home movies subvert dominant notions of belonging. In an era of de jure and de facto segregation, the simple act of Black families enjoying spaces that were often hostile to them can be seen as a powerful avenue of resistance. These films highlight a paradox: while African Americans were fighting for their rights and facing rampant discrimination, they were also celebrating milestones, cherishing family outings, and asserting their right to joy and relaxation. These historical home movies, while appearing as simple recordings of family leisure, act as noteworthy assertions of Black identity, resilience, and belonging in America. They remind us that resistance can manifest in subtle yet powerful ways—in a family’s shared moments of joy and mere presence in spaces they were told they didn’t belong. By recognising the importance of home movies in media scholarship, we expand our understanding of how concepts like belonging, cultural memory, national identity, and the role of African American home movies are interconnected in revealing a more inclusive American history.

African American Leisure Practices and Belonging

During the postwar period, the American road trip became increasingly popular (Rugh 2). As more Americans acquired cars, which led to the creation of networked highways across the US, national parks became a popular tourist destination. This infrastructure made it possible for families to take longer vacations and visit more distant national parks, cementing their importance as a symbol of American identity and a source of national pride. Families packed up their cars and drove to national parks such as Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, where they would camp, hike, and explore the natural surroundings. As historian Susan Sessions Rugh claims, “family travel helped Americans understand their status as citizens in the American nation”, and visiting national parks “cultivate[d] civic identity and attachment to American history” (13). While African American families, as captured in the home movies discussed in this article, also engaged in these travel practices, their experiences included additional complexities. For middle- and upper-class African American families, travel was not just a leisurely pursuit but also a means of asserting their rights as US citizens and engaging with the American Dream. However, this dream, symbolised by celebrated national landmarks, conveyed a more complicated meaning for people of colour. While celebrated as ideal American landscapes, these places were also reminders of the nation’s racist history. Despite the barriers of structural racism, African American families chose to travel, navigating the desire for national belonging and the stark realities of their lived experiences.

Segregation was not consistent across the United States and underwent modifications over time. The locations and demographics involved influenced the types and extent of segregation. Before the 1930s, indigenous peoples and African Americans were openly discouraged from visiting national parks, although this practice was not publicly acknowledged (Young 652). In the 1930s, as Congress established new national parks in the South and camping emerged as a symbolic leisure activity epitomising American ideals like community, democracy, and self-reliance, the systemic racism that restricted people of colour access to these parks became a glaring and contentious issue. However, racism was not limited to the South. For example, historian Terence Young recounts how a group of African American campers was denied a permit to stay at Yellowstone National Park by a National Park official who used “subterfuge” to deny their application by filling up the entire summer schedule with dummy groups (663).

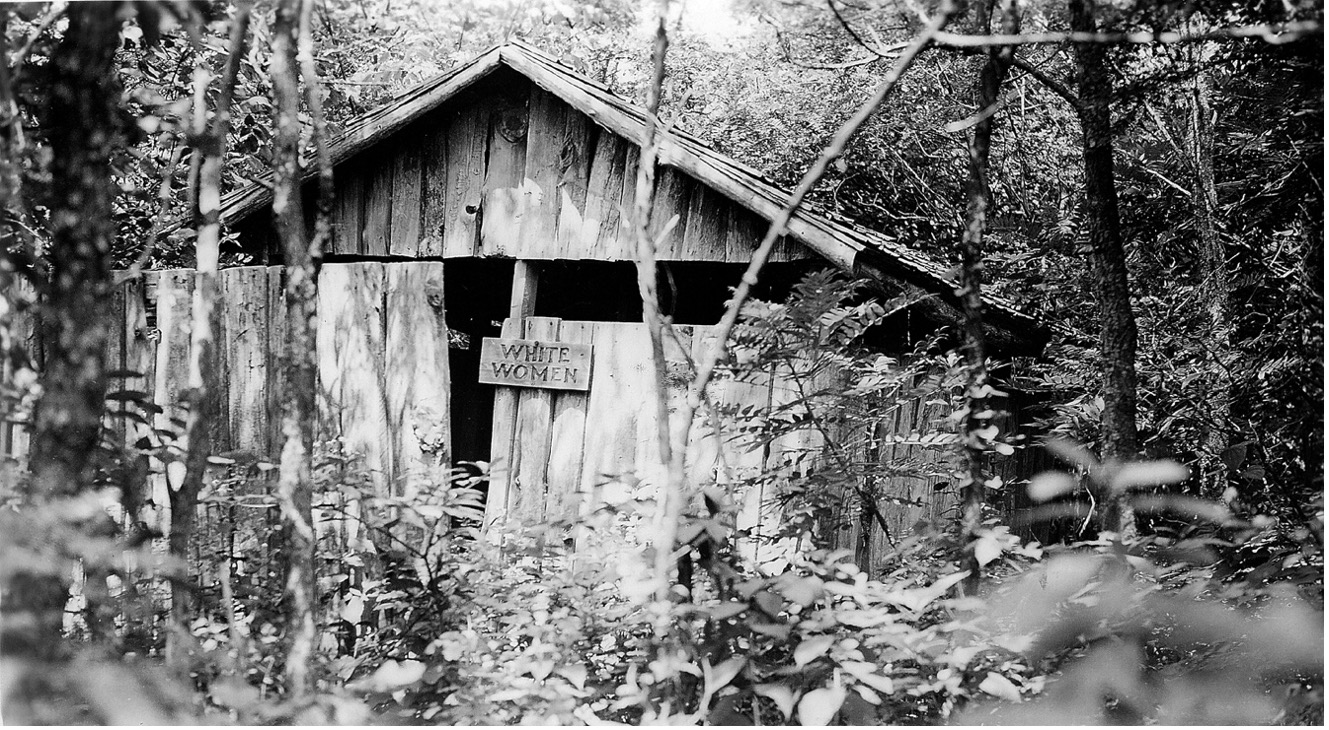

Figure 2: “Segregated restroom facility at Shenandoah National Park, 1940s.”

Courtesy of the National Park Service Archives.

Yet, the denial of access to spaces of leisure was not a mere inconvenience; it represented a pervasive form of systemic oppression, limiting African Americans’ right to partake in experiences many took for granted. Leisure studies scholar Rasul Mowatt claims that “leisure is the articulation of power […] it determines how we see and think of ourselves, what we can do, and where it can be done” (664). For African Americans, the pursuit of leisure represented the achievement of “the good life, upward mobility, and prosperity” (670). Consequently, Black people during Reconstruction persisted in finding ways to enjoy leisure time, much to the annoyance of many of their white counterparts (Foster 135). This was one of several conflicts concerning public accommodations that culminated in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling of 1896, which legalised segregation in public spaces until 1954. By the early twentieth century, Black Americans became increasingly determined to overcome systemic racism in all aspects of everyday life, which includes taking part in leisure activities. Activities like picnics, music, movies, trips to amusement parks, and other forms of entertainment provided temporary relief from the stress of segregation (131). For African Americans who owned a car, a road trip provided a sense of adventure and escape, free from daily stress (141). During the postwar period, many of these road trips included national parks as a destination.The process of cultural memory involves negotiation among different narratives competing for a place in history, but it is also intertwined with complex political stakes and interests (Sturken 1). Historically, Black people were absent from dominant representations of park tourism even though the creation of national parks involved significant contributions from African Americans. For example, Charles Young served as the first African American superintendent of Sequoia National Park in 1903. Formerly enslaved Stephen Bishop discovered Mammoth Caves in central Kentucky (Mills). Furthermore, many of the parks stand as poignant reminders of the ancestral lands that Indigenous communities have been forcibly dispossessed of. However, while representing a history of displacement and erasure, these spaces can also serve as important sites of memory for marginalised communities and their histories, providing a place for them to connect with their cultural and spiritual heritage and assert their place in the national narrative. As Marita Sturken notes, cultural memory “both defines a culture and is the means by which its divisions and conflicting agendas are revealed” (1). This can be especially powerful for individuals whose cultural heritage has been marginalised or erased, as these places can provide a sense of connection to their roots and a deeper understanding of their history.

Home movies, like the Jean Patton Collection, serve as tangible sites of memory. The Patton Collection, for example, offers an intimate glimpse into the lives of its subjects, presenting not just familial events but also the cultural, social, and historical milieu of the time. French historian Pierre Nora introduced the term “sites of memory” or “lieu de mémoire” in his seminal work, Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past. Nora’s concept refers to both physical and symbolic locations where collective memory is preserved and perpetuated (xvii). This encompasses a wide range of manifestations, from monuments and museums to commemorative events and archives like the Jean Patton Collection. According to Nora, sites of memory are created when a group of people preserves a specific aspect of their past that they consider significant. These sites may commemorate people, events, places, or traditions that hold a particular meaning for the community. Another critical aspect of sites of memory is their role in creating a sense of belonging and continuity for the community that preserves them. They help create a shared cultural heritage and cultural memory that reinforces the group’s identity, values, and traditions.

Some scholars, such as Geneviève Fabre and Robert O’Meally, argue that sites of memory are created not only by dominant groups or governments but also by marginalised groups who use them to preserve their history and identity. As Fabre and O’Meally argue, Nora’s concept is a valuable tool for understanding how memory is constructed, transmitted, and contested in different societies (6–7). It highlights the importance of examining not only the dominant narratives but also the marginalised voices and alternative memories that exist in society. Fabre suggests using Nora’s concept of sites of memory as a starting point for examinations into African American history and collective memory (7). For historians of African American culture, the idea of lieu de mémoire opened new categories of sources for historians, including dance, art, architecture, oral expressions, novels, poems, and autobiographies, which are “repositories of individual memories” that create a “collective communal memory” (Fabre and O’Meally 9). In the context of the experiences of African Americans during the Civil Rights era, Fabre and O’Meally’s approach to cultural memory expands our understanding of how marginalised communities can use various cultural expressions to challenge dominant historical narratives. By incorporating home movies as repositories of personal and collective memories, historians can access a more diverse range of voices and perspectives that were previously obscured in official histories.Cultural memory is inherently tied to the notion of imagined communities. Benedict Anderson’s influential work Imagined Communities provides a theoretical framework for understanding the emergence and significance of national identity and cultural memory in the modern world. Anderson claims that members of a nation construct, preserve, and perpetuate a collective narrative that forms the basis of their cultural memory (204–205). This memory serves to solidify their national identity, binding individuals together by anchoring them to a shared past (6–8). National identity is an essential aspect of imagined communities, as it shapes a shared sense of belonging among citizens of a particular nation. One can observe the interplay between imagined communities, national identity, and cultural memory in various contexts. For example, national parks serve to reinforce a nation’s shared narrative, instilling a sense of pride and belonging in its citizens. Therefore, national parks can also be understood as sites of memory, as they often hold symbolic significance for a nation and its populace.

National parks have been integral to American identity since their creation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These protected areas of wilderness played a significant role in shaping American identity. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act, establishing Yellowstone National Park as the world’s first national park. The park’s creation was a milestone in American history, as it marked the first time a nation had set aside land specifically for conservation purposes (Meringolo 52). Over the next several decades, more national parks were established across the country, including Yosemite, Sequoia, and Grand Canyon, and the establishment of the National Park Service (“Quick History"). These parks were seen as a way to portray America’s monumentalism and promote tourism, but they also served a deeper purpose. As Carolyn Finney argues in Black Faces, White Spaces, the prevailing environmental discourse in the US is primarily shaped and influenced by white and Euro-American perspectives (3). “This narrative not only shapes the way the natural environment is represented, constructed, and perceived in our everyday lives, but informs our national identity as well” (Finney 3). National parks became a symbol of white American identity. In the Jean Patton Collection, there are snippets that, while not overtly political, subtly resist the national parks’ predominantly white narrative, showcasing Black families enjoying leisure moments, thus pushing against this complicated historical backdrop.

The relationship between African Americans and the outdoors presents a nuanced and contrasting narrative. Sociologist Cassandra Johnson argues that African Americans have weaker emotional ties to outdoor places than white people, partly because their “collective memory” of wilderness is marked by slavery, Jim Crow, and lynching (qtd. in Cavin and Scott 2). The writings of Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois highlight the historical origins of African Americans’ complex relationship with the outdoors. Douglass’s writings expressed positive feelings towards nature within the context of leisure, which was rare for enslaved people in his time (Cavin and Scott 3). However, since enslavers used leisure time to dissuade escape, Douglass had mixed feelings about it. The woods represented both a “path to freedom” and a place of fear and forced labour, resulting in a complicated relationship with nature (4). This duality is further supported by the cultural and historical context of the time. As Finney notes, “arguably, lynching succeeded in limiting the environmental imagination of black people whose legitimate fear of the woods served as a painful and very specific reminder that there are many places a black person should not go” (60). In his book Darkwater, Du Bois explains why people who have been beaten down by the cruelty of the world do not travel to beautiful places and immerse themselves in the “utter joy of life” (228). He expresses his deep love for the Grand Canyon and describes it as the one thing that “will live eternal” in his soul (237). He believed that the grandeur and beauty of nature could serve as a basis for hope and that even in the face of brutal oppression, nature can be a source of healing. Despite acknowledging the ambivalent feelings many African Americans had towards nature in the early twentieth century, Du Bois recognised the redemptive potential of natural places in the face of segregation (Cavin and Scott 6).

Home movies, such as those found in the Jean Patton Collection, stand as powerful testaments to the multifaceted experiences of African Americans with the outdoors and leisure spaces. In both films from the collection that document their trip to Yellowstone National Park, the primary focus is the captivating landscape and the wild animals. Like many other tourists, one notable scene shows the couple captivated by a bear and her cub approaching a car parked along the road. Although the films predominantly centre on nature and wildlife, the couple make a brief appearance during leisure moments: sharing a meal beneath a tree with friends, at a picnic table, and as they watch the iconic eruption of Old Faithful. These understated scenes convey a deep significance. Despite the everyday reality of systemic racism, these films directly depicts the couple’s determination to find moments of enjoyment and relaxation. By documenting their experiences in Yellowstone, the Pattons not only challenge the prevailing narrative that equates national parks with whiteness and national identity but also craft their own sites of memory. As mementos of their lived experiences, these home movies anchor them to these national landscapes, fostering a personal and collective sense of belonging and asserting their place in the American narrative.

Home Movies as Technologies of Resistance

Throughout the mid-twentieth century, the depiction of the American West in films and television was often used to represent the ideal national identity (Courtney 42). The popularity of Westerns transcended boundaries like gender, class, and race, promoting the West as the foundation of American identity (Rugh 94). In 1959, about 25% of TV content was Westerns. By 1960, they captivated more than a third of all TV viewers, with eight out of the top ten shows being Westerns (92). However, the rise in popularity of Westerns during the mid-twentieth century was not confined only to professional programming. This national fascination is also reflected in the personal visual records of the era. A home movie from the AAHMA collection provides a glimpse into this phenomenon (“014_AAHMA”). The 20-minute and 31-second orphan home movie depicts African American tourists as they embark on a road trip to the Western US during what appears to be the early 1960s.

Figure 3: “Man with a cowboy hat taking pictures.” 014_AAHMA. 1960s, 8 mm colour film.

Private Collections, African American Home Movie Archive.

The movie begins with a group of unidentified men on a hunting trip, staying at the Mountain View Motel, a lodging establishment listed in the AAA Travel Guide, which allowed African American travellers to find accommodations despite widespread racial segregation. As the camera pans away from the men gathered around their car inspecting the game in the trunk, the snow-capped mountains and the motel sign come into view. The scene then shifts to a man wearing glasses and a cowboy hat, filming other group members (Fig. 3). This scene is followed by a highway view from a moving car, showcasing the freedom these African American tourists enjoyed while travelling across the country. Filmed primarily from the passenger side facing forward, the camera captures various landscapes, including mountains and the Missouri River, as well as a sign welcoming visitors to Mount Rushmore and still shots of the iconic monument featuring the four presidents. In the home movie, the experience of African American tourists is highlighted, from their stay at a racially inclusive motel to their exploration of iconic Western landscapes. Through their personal lens, they captured their experiences of the American West. This act ties into Susan Courtney’s theory that “seeing” the West for oneself and then recording it through home movie cameras became the “exemplary mode of being an expert American” (49). The home movie places the viewer right into the heart of America’s idealised West. Through their camera lens, they are not just tourists but become representative of the broader American experience, connecting personal narratives with national identity.

It is important to acknowledge that the link between the West and the assertion of American identity, exemplified by African American travellers documenting their journeys, was not a new concept to the community. Early African American filmmakers had been exploring similar themes, a testament to how deep-rooted and lasting these connections were. Historically, Black filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company depicted the Western frontier as an idyllic space that stood in stark contrast to the urban environments, even though many African Americans were migrating to cities during that period (Stewart 191). Micheaux, in particular, held the West as a sanctuary where African Americans could flourish and claim their rightful American identity (Stewart 225). Moreover, early Black filmmakers, in their attempts to resonate with a dispersed Black audience, made concerted efforts to emphasise the inherent “Americanness” of their characters and stories (225). They often utilised narratives of migration and patriotism, drawing clear parallels with the previously discussed African American tourists’ journey to the West. Therefore, home movies of African American tourists venturing into the West are not isolated events but are part of a larger cultural history.

Black filmmakers’ representation of African American migration and the West in early films provides a cinematic precursor to the themes depicted in the home movies from the SSHMP, AAHMA, and NMAAHC examined in this article. Historically, these films portrayed the West as a symbolic landscape where African Americans sought to carve out their place in the American narrative. It is a testament to the continuous and evolving relationship between mobility, identity, and the American dream for the African American community. The portrayal of the West in these films highlights a deeper narrative, where mobility was not merely material but also sociocultural. This cultural backdrop enriches our understanding of the home movies. When African American tourists celebrated “mobility and the freedom of the open road”, they were not just asserting their right to movement but also participating in a broader historical dialogue, one that had been depicted in early Black films (Bay 3). As historian Mia Bay argues, the right to freedom of movement has historically been regulated, limited, and policed for African Americans (3). Like the early Black films, the home movies serve as powerful reminders of the challenges presented by structural racism and the constant pursuit of belonging. Mobility has played a significant role in racialisation throughout the twentieth century, working in conjunction with place to influence cultural memory and foster a sense of belonging among diverse racial groups (Carpio 14). African Americans’ ability to be considered citizens, in other words, their sense of belonging within the nation, was tied to their participation in automobility, which combined self-determination, mobility, consumption, and social interaction. White supremacy has tried to limit Black mobility, but African Americans affirmed idealised spaces of freedom, such as national parks, through automobility (Seiler 1099).

It is important to note that national parks were often dominated by white families. In the films, the Pattons, the Nashes, and the Grahams were among the few or only families of colour present. For example, one of the films from the Graham family home movies (NMAAHC) during the 1960s commences with a heart-warming scene of three girls dressed immaculately in their Sunday best, departing from their home and walking along a city sidewalk (“Graham Family Collection”). Their cheerful waves to the person behind the camera offer a glimpse of everyday family relations. This domestic scene transitions to what seems to be the beginning of a vacation, characterised by prairie land and haystacks visible against a vast blue sky, and even a humorous check on an outhouse’s availability. As the film unfolds, we witness scenes of the family enjoying leisure moments, like fishing in a national park or visiting Mount Rushmore. The only Black family in the crowd of viewers gazes at the memorial from a viewing platform. The film then cuts to a geyser erupting—presumably Old Faithful. In the next shot, at least fifty people encircle the geyser. The camera then captures a bear causing traffic as it attempts to cross the street. The Graham family appears to be the only people of colour in each of these spaces.

To truly grasp the meaning of these images, one must recognise both the visible and the concealed. It is jarring to note the lack of diversity in these home movies. This absence is highly indicative of segregation of the period and exemplifies the economic challenges many Black Americans faced as only a limited number could afford such leisure trips, highlighting the degree of economic inequality of the period. While the film overflows with joy and family bonds, it does not explicitly depict the likely challenges stemming from the pervasive structural racism of the period despite the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The absence of racial confrontations in these films does not mean they did not exist; rather, it could signify an intentional choice to focus on joy and resilience in the face of adversity. By examining the history of segregation and the contentious racial politics surrounding national parks, we begin to see the significance of these moments of Black leisure. Engaging in such activities at iconic American landmarks when their rights as citizens were heavily curtailed is not just leisure—it is a subtle yet powerful act of resistance. The seeming discontinuity in the shots, indicative of spliced footage, further suggests a constructed narrative—one of joy and resistance against the socio-political backdrop of the Civil Rights era.

Conclusion

The rise of the American road trip during the postwar period and the increasing accessibility of national parks contributed to the formation of national identity and cultural memory. For middle-class African American families, these road trips allowed them to assert their rights as US citizens and participate in the American Dream. Drawing on Nora’s concept of sites of memory and Anderson’s theory of imagined communities, as well as archival collections, the analysis emphasises the importance of home movies as a means of resistance and belonging, empowering marginalised communities to create and share their narratives beyond mainstream representation in television and film. The significance of documenting tourism experiences for African Americans becomes evident when considering the limitations imposed on their travels through the 1960s. The examination of home movies in this article reveals the critical role of mobility in fostering a sense of belonging for African Americans during an era characterised by de facto and de jure racial segregation. By extension, home movies were more than just personal memories—they were a powerful means of creating a sense of belonging and community in the face of widespread discrimination. The archival footage shows the resilience and determination of these families to find time for leisure as they navigated national parks. Their experiences contribute to a more inclusive understanding of national identity, contesting the predominantly white narrative associated with environmental discourse and national parks and underscoring the significance of acknowledging all Americans’ diverse histories and leisure experiences in shaping the nation’s cultural memory.

Note

[1] While the Dr. Helen Nash Collection (SSHMP) offers a rich collection of home movies detailing African American family vacations during the racially segregated 1960s to notable destinations such as the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone National Park, and Mount Rushmore, it couldn’t be delved into extensively within the main body of this article due to space constraints. Despite its similarities to the Patton Collection, Nash’s films have unique filming techniques, from establishing shots to accidental Dutch angles. Noteworthy is the 1968 road trip footage to the western US, characterised by its unintentionally shaky style. These films, while briefly discussed here, masterfully capture the family’s travel experiences against a backdrop of vast natural landscapes.

References

1. African American Home Movie Archive. “014_AAHMA.” Private Collections. www.aahma.org/privatecollections.

2. Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Verso, 2006.

3. Bay, Mia. Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance. Harvard UP, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674258709.

4. Black Home Movie Index. African American Home Movie Archive, 6 June 2023, www.aahma.org/black-home-movie-index.

5. Carpio, Genevieve. Collisions at the Crossroads: How Place and Mobility Make Race. U of California P, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520970823.

6. Cavin, Drew, and David Scott. “An Analysis of Nature in Three African American Autobiographical Narratives.” Journal of Unconventional Parks, Tourism & Recreation Research, vol. 3, no. 1, 2010, pp. 2–7.

7. Courtney, Susan. Split Screen Nation: Moving Images of the American West and South. Oxford U P, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190459963.001.0001.

8. Du Bois, W. E. B. Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. 1921. Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 2006.

9. Fabre, Geneviève, and Robert O’Meally, editors. History and Memory in African-American Culture. Oxford UP, 1994.

10. Finney, Carolyn. Black Faces White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. U of North Carolina P, 2014. https://doi.org/10.5149/northcarolina/9781469614489.001.0001.11. Foster, Mark S. “In the Face of ‘Jim Crow’: Prosperous Blacks and Vacations, Travel and Outdoor Leisure, 1890–1945.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 84, no. 2, 1999, pp. 130–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2649043.

12. Great Migration Home Movie Study Collection. “Graham Family Collection.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. sova.si.edu/record/NMAAHC.SC.0001.

13. Meringolo, Denise D. Museums, Monuments, and National Parks: Toward a New Genealogy of Public History. U of Massachusetts P, 2012.

14. Mills, James Edward. “These People of Color Transformed U.S. National Parks.” National Geographic, 4 May 2021, www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/people-of-color-who-transformed-us-national-parks#:~:text=One.

15. Mowatt, Rasul A. “A People’s History of Leisure Studies: Leisure, the Tool of Racecraft.” Leisure Sciences, vol. 40, no. 7, 2018, pp. 663–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1534622.

16. Nora, Pierre. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past. Vol. 1: Conflicts and Divisions. Edited by Lawrence D. Kritzman, translated by Arthur Goldhammer, Columbia UP, 1996.

17. “Quick History of the National Park Service.” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/articles/quick-nps-history.htm. Accessed 11 Nov. 2023.

18. Rugh, Susan Sessions. Are We There Yet: Golden Age of American Family Vacations. U P of Kansas, 2010.

19. Scott, David and KangJae Jerry Lee. “People of Color and Their Constraints to National Parks Visitation.” The George Wright Forum, vol. 35, no. 1, 2018, p. 73–82.

20. Seiler, Cotten. “‘So That We as a Race Might Have Something Authentic to Travel By’: African American Automobility and Cold-War Liberalism.” American Quarterly, vol. 58, no. 4, 2006, pp. 1091–117. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068407.

21. South Side Home Movie Project. “Dr. Helen Nash Collection.” University of Chicago. sshmpportal.uchicago.edu/index.php/Detail/collections/5.

22. ——. “Jean Patton Collection.” University of Chicago. sshmpportal.uchicago.edu/index.php/Detail/collections/8.

23. Stewart, Jacqueline Najuma. Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity. U of California P, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520936409.

24. Sturken, Marita. Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the Aids Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. U of California P, 1997.25. Vacation (1966) Titles. “Jean Patton Collection”, South Side Home Movie Project, sshmp.uchicago.edu/archive/SSHMP-2016-PATTON-00005.

26. Young, Terence. “‘A Contradiction in Democratic Government’: W. J. Trent, Jr., and the Struggle to Desegregate National Park Campgrounds.” Environmental History, vol. 14, no. 4, 2009, pp. 651–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40608542.

Suggested Citation

Patton, Elizabeth. “Home Movies as Technologies of Belonging and Resistance.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 90–102. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.06

Elizabeth Patton is an Associate Professor of Media and Communication Studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Her research interests center on media history, identity and space, and how media practices have informed popular understandings of work and leisure. She is the author of Easy Living: The Rise of the Home Office (Rutgers University Press, 2020) and the recipient of the 2023 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. She currently serves as co-managing editor of Mediapolis: A Journal of Cities and Culture.