“Beyond the Kitchen Door”: Racialised Female Domestic Labourer’s Mobility Experiences in Anna Muylaert’s The Second Mother

Francianne dos Santos Velho

[PDF]

Abstract

The successful Brazilian fictional film The Second Mother (Que horas ela volta?, 2015), directed by Anna Muylaert, illustrates that mobility is chiefly limited or stagnant for the main character, Val (Regina Case), a live-in racialised female domestic labourer who migrates from the Brazilian northeast to the southeast to work in the house of a wealthy family in São Paulo. However, the film subtly shapes Val’s mobility as a more active, unrestrained experience once her daughter arrives in town ten years later. My goal is to understand the fundamental factors influencing Val’s range of motions. Building upon on the cultural geography notion of mobility as a socially produced movement of time and space, I look at how control over Val’s ability to move derives from the embodiment of practices of power built on derogatory discourses around the ideas of the doméstica (“maid”) and the domestic spatial and interpersonal emotional relations ingrained in class, gender, and the racial dimensions of Brazil’s former colonial, plantation-based patriarchal society. On the other hand, Val begins to disembody the powerful practices that previously controlled her mobility. I argue that the spatial, social, emotional, and bodily mobility gained by Val, echoing the Brazilian period of empowerment for the working classes, reflects gains from law such as PEC das Domésticas EC 72/2013 and Lei Complementar 150/2015.

Article

The successful Brazilian fictional film The Second Mother (Que horas ela volta?, 2015), directed by Anna Muylaert, illustrates that mobility is chiefly limited or stagnant for the main character Val (Regina Case), a live-in racialised female domestic labourer who migrates from the Brazilian northeast to the southeast to work in the house of a wealthy family in São Paulo. However, the film subtly shapes Val’s mobility as a more active, unrestrained experience once her daughter Jessica (Camila Mardila) arrives in town ten years later. My goal in this article is to understand the fundamental factors influencing Val’s range of motions in The Second Mother. According to the cultural geographer Tim Cresswell, mobility is a socially produced movement of time and space, an interface between the mobile physical body and the represented and practised mobilities controlled by practices of power (On). Building upon this notion, this study addresses the overarching question: how does the film depict Val’s experience of mobility as a racialised female domestic labourer? Researching this question involves delving into Val’s purest level of movement, gestures, and actions, such as sitting, standing, serving, swimming, walking, and swinging; at the representational level, such as resigning/transgressing, arresting/freeing, and belonging/discovering; and at the level of experience, that is, the process of embodiment and disembodiment of practices of power (Cresswell, On 5).

I start by investigating how Val’s restricted and stagnant mobility is delineated before Jessica’s arrival. I draw my argument from the film’s use of predominantly still camera shots and the framing of the domestic worker’s repetitive motions, often physical activities related to household duties. Her actions remain consistent: starting the day by serving breakfast and concluding it by clearing the dinner table. A sense of entrapment is also highlighted as Val lives in a tiny, cramped prison-like bedroom, and adheres to a monotonous daily routine centred around the kitchen and service area. In a dialogue between the two, Jessica asks if it was from books that Val learned the rules concerning “cannot do this, cannot do that”, and her mother answers: “This here, one does not need to have explained, one is born knowing what she can and cannot do” (1:07:00). Unwritten rules control her position as a racialised female domestic worker, both at home and in society. Although not explicitly mentioned, Val knows the dos and don’ts that regulate her body and practices. For example, whether she can sit or stand, fulfil or decline tasks, and what specific spaces she is permitted or denied access to, such as the pool and the dining room. I look at how control over Val’s ability to move derive from the embodiment of practices of power built on derogatory discourses around the ideas of the doméstica (“maid”) and the domestic spatial and interpersonal emotional relations ingrained in class, gender, and the racial dimensions of Brazil’s former colonial plantation-based patriarchal society. These discourses perpetuate the stereotype of Black women as “maids”, which historically has been associated with the derogatory image of the “Black Mammy”—a symbol of “contamination” and “dirt”. (Roncador). They also trace the continuation of intimate “cordial” relations between the employer (master) and employee (maid), with the tiny “maid’s room” symbolising the contemporary rendition of the landowner’s house and the enslave quarters (Rara; Schwarcz, O espetáculo).

I will then explore the idea that Val’s return to bond with her daughter after many years of absence increases her range of mobility. Jessica is an intelligent and assertive young woman who recognises her life as worthy of dignity and free from mistreatment. She says: “I don’t think I am better, okay? I just don’t think I am worse; do you understand?” (1:16:00). Jessica moves to live with her mother in Sāo Paulo, not to follow in her mother’s footsteps but to pursue higher education, as her dream is to become an architect. Unlike Val, Jessica crosses, challenges, and reclaims the employer’s house material and symbolic spaces. She occupies every room within the house by graciously embracing the offers to stay in the guest room and dine in the dining room with her employer. The racialised girl from a rural area partakes in items typically associated with affluent urban white culture, such as art books, gourmet ice cream, and lemonade. At the film’s cathartic point, Jessica upsets upper-middle-class hierarchies when she is unexpectedly propelled into the pool, an architectural element that symbolises Brazilian society’s hierarchy of social privileges. Jessica’s silent transgressive actions make visible the silent practices of power that have been controlling Val’s movements, practices, and meanings.

In the article, I reveal how Val gradually begins to contest the dominant accounts of domesticity and to disembody the controlling forces that had previously constrained her mobility, triggering her ultimate dislocation “beyond the kitchen door” (1:16:00). Val’s physical motions increase dynamism and disengage from her household responsibilities. To convey the emphasis on Val’s self in motion, specific film techniques are utilised, such as accelerated takes, a travelling camera, vibrant colour schemes, and close-up shots. Val steps into the pool, finds a seat, liberates her body movements, refrains from domestic duties, resigns from her job, takes charge of her financial autonomy, pursues a new career path, forges a profound physical and emotional bond with her daughter, and assimilates into the city and its community life. I argue that the unbound mobile journey undertaken by Jessica and Val in The Second Mother reflects Brazil’s historical, economic, political, social, and cultural context of empowerment of domestic workers due to the progress made in the fight for their rights through PEC das Domésticas EC 72/2013 and Lei Complementar 150/2015 (Silva, Cirilo, and de Avila). It also aligns with the evolving socio-political perspective in Latin American films, which turns the narrative lens towards examining daily household interactions to grasp the profound and frequently hidden aspects of national and social inequalities (Shaw).

I argue that it is important to recognise Val’s disruptive actions, especially when we realise that the mobile experiences of female domestic laborers who are racialised can provide new insights into the current debates around marginalised groups’ mobility. Consequently, the private domain can be seen as a space of resistance (Cresswell, “Embodiment”). Drawing on Juliana Teixeira, it is within the ruptures of slavery pacts that we can discover new perspectives that redefine critical paths for transformation. This is especially relevant in a context where paid domestic labour holds a dominant position in labour relations, making it constantly necessary to acknowledge and recognise it as such and grasping the imperative need to understand the repeated class, gender, and racial colonial legacies, and craft alternative pathways for domestic labour in Brazil (Cal and Brito; Teixeria 200).

To understand the film’s politics of mobility expressed in its discourse and aesthetic strategies, I take a transdisciplinary approach combining cultural studies with the ways in which class, gender, and race intersect with the aspects of mobility, and cinema, a social practice of aesthetically creating and recreating cultural meanings (Tuner). Therefore, I begin this article by outlining some of my theoretical underpinnings to situate the dynamics of mobility in Brazil and its association with the narratives constructed around domestic space, interpersonal emotional connections, and the figure of the doméstica. This follows a commentary on the social, political, and cultural context of The Second Mother. I then turn to a close reading of Val’s restricted or inert mobile experiences before her reunion with Jessica, and finally examine the transformation of her mobility after her daughter’s arrival towards a more unregulated and fluid experience.

Domestic Labour in Brazil: Class, Gender, Race, and Mobility

Val, a light-skinned Black female in The Second Mother,migrated from Brazil’s northeast to the southeast for better living conditions. Val had no other option but to allow a female friend to raise her daughter while she cared for her employer’s son far from her home at her new workplace and residence: a tiny “maid’s room” in a wealthy home. Her story reflects the experiences of many women who left agrarian Pernambuco for industrialised São Paulo during a major internal migration wave of northeastern individuals in the late twentieth century (Oliveira and Jannuzzi) who faced the racialisation and discrimination because of their appearance, language, and jobs (Mendes).

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Cleonice, a sixty-three-year-old Black woman who worked as a domestic labourer, was the first confirmed death in Rio de Janeiro. The source of the infection was her employer, a white woman who had recently returned from a vacation in Italy and for whom Cleonice had been working for more than twenty years. She commuted two hours daily from the city’s periphery to her employer’s house in the neighbourhood with the highest cost per square meter in Brazil. Despite the danger of working in an infected household, Cleonice continued her work as she had no other means of survival (Rogero). Despite the different contexts, aspects of the mobility experiences of Val and Cleonice bear a striking resemblance as they are based on the politics of distance and closeness and the possibility of racialised female domestic labourers choosing to stay or leave. Both scenarios illuminate mobility dynamics, part of the social production process of time and space, which “becomes meaningful within systems of domination and resistance, inclusion and exclusion, and is embedded with systematically asymmetrical power relations” (Cresswell, “Mobilities” 9).

The Second Mother and Cleonice’s case sparked debate on how class issues impact domestic labourers navigating public or domestic spaces (Costa; De Luca; Slattery and Gaier; Vazquez). My argument asserts that their mobility dynamics are not exclusively determined by class. Instead, gender and race components present in traces of Brazil’s former colonial society are profoundly embedded in determining who moves, when they do so, how they go about it, and the reasons behind their movement. They are set into motion by practices of power, which come into play to prescribe meanings for their bodies and practices based on the consent or refusal of the position of doméstica—the female condition inherently linked to caregiving responsibilities and undeniably interconnected with discriminatory socio-cultural perceptions related to “blackness” (Roncador 14). The film The Second Mother is a compelling example because Val’s mobility is initially limited, and, subsequently, she discovers methods to move more freely. The character grapples with the complexities of remaining and departing, of being near and far— a challenge that Cleonice and many other domestic labourers cannot contest because they experience persistent material and symbolic forms of exploitation. In the following section, I will address how Val’s range of mobility is constructed. However, first, it is necessary to explore how the narratives around the doméstica were shaped within the Brazilian context and to understand the circumstances that framed the film in 2015.

Today, an estimated 75.6 million domestic workers exist worldwide, nearly eighty percent of whom are low-income women engaged in tasks traditionally considered women's work. These tasks range from cooking and cleaning to caring for children, the elderly, and the sick, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). Brazil has the world’s highest number of domestic workers: about 5.2 million women (OIT). In 2021, Black women represented up to 65% of the total (DIEESE). As previous research has noted, living in a traditionally tiny “maid’s room”, tucked away at the back of the house, represents the modern iteration of the landowner’s house and the enslaved quarters of the earlier plantation-based society. Seemingly intimate relations between the employer (master) and the employee (maid) reflect paternalistic, fossilised colonial social structures within the home that still resonate today in the frequent reference to domestic labourers, despite not being treated as such, as being “part of the family” (Rara; Schwarcz, O espetáculo). Live-in domestic labourers who sometimes spend a lifetime in the service of the same household constituted a mere 1% of Brazil’s domestic labour force in 2019 compared to 12% in 1995 (Pinheiro 18). Nowadays, most labourers are diaristas, domestic workers who are employed in multiple households and, in most cases, do not have a formal employment arrangement with any of them. However, despite the significant change in the social significance of domestic work as more transient and less subordinate, the historically imagined constructs strengthened by the enduring structural inequality of domestic workers persist (Teixeira 55).

After the abolition of slavery in 1888, the housemaid’s image was associated with “contamination” and “dirt”, due to the Brazilian project of (re)construction, modernisation, whitening, bourgeoisification, and restoration of the nation, which changed domestic dynamics. In this context, the white and bourgeois family’s chief image was created based on spatial opposition with the former enslaved, Black and poor servant who now is not part of the family clan and lives in the streets and tenements (Roncador 20–25). Furthermore, between the 1920s and the 1930s, the flow of nationalist ideologies inaugurates a celebratory image around relations between white and Black people in the intimate space of the patriarchal Brazilian family (Roncador 79–81). From Gilberto Freyre’s renowned book The Master and the Slaves (1933) a colonial myth of the “Black Mammy” resurged, a benevolent and subservient wet nurse, who is responsible for the nurturing and education of the master’s children (Roncador 91).

The Brazilian “desire for intimacy”, the aversion to formality in relationships, and the preference for effusive and personable contact refer to the often-quoted notion of “cordiality” developed in Sergio Buarque Holanda’s cultural theory. In the Roots of Brazil (1936), Holanda demonstrates that “cordial” relations are rooted in a colour-coded culture based on the power of a small elite, whose influence was sustained by eliminating any distinction between private and public spheres. Through the seemingly informal practice of “seeking and conceding personal favours into all realms of public and business life”, cordiality can include both affectionate/intimate and violent/coercive behaviour, which carries hierarchical forms of sociability within the Brazilian private domain (Sá; Schwarcz, “Sérgio Buarque de Holanda”).

In The Second Mother, Val’s embodiment and disembodiment of these discourses play a role in determining her mobility. Embodiment relates to “the process whereby the individual body is connected into larger networks of meaning at a variety of scales. It refers to the production of social and cultural relations through and by the body at the same time as the body is being ‘made up’ by external forces” (Cresswell, “Embodiment” 176). The charismatic, hilarious, and zealous Val represents the Black Mammy; a benevolent house cleaner, cook, and nanny. Working for more than ten years in the same position, Val fostered a “cordial” relationship with her employers Barbara (Karine Teles) and Ze Carlos (Lourenço Mutarelli) and affectionately raised as a mother the couple’s son Fabinho (Michael Joelsas). The unwritten rules rooted in the idea of the domestica as a symbol of “contamination” and “dirt” leads Val to never use the family’s leisure spaces for her enjoyment, namely the swimming pool, which is a marker of her employer’s class privilege (Vazquez). Upon Val’s reunion with her daughter Jessica, the labourer redefines the established spatial norms within the household and challenges the marginalised roles and limitations placed on domestic bodies, both in terms of what they can and cannot do. She promotes the disembodiment of crystallised narrative remnants of colonial influence on gendered and racialised dynamics.The unbound mobile journey undertaken by Jessica and Val reflects the new ground the fights for domestic workers’ rights gained in the Brazilian context of the film’s production and release period—a workforce that historically sustained itself within the informal market and had traditionally been denied all fundamental rights. Proposed by the PEC das Domésticas EC 72/2013 and Lei Complementar 150/2015,domestic work was made equal with other labour categories and guaranteed basic entitlements such as a 44-hour working week, paid vacations, maternity leave, and insurance in case of unemployment (Silva, Cirilo and De Avila). Additionally, this moment marks the significant economic advances of the Worker’s Party left-wing Lula era (2003–2011):

A seismic shift that shook the structures buttressing Brazil’s social divide, which fuelled class conflict. Firstly, the marketplace, historically targeted at the upper- and middle-classes in the country (or A and B classes, as they are known in Brazil), had to come to terms with a new reality wherein the tastes and interests of lower middle-class consumers (the C class) now accounted for a sizable share of the market. Secondly, public spaces previously enjoyed only by the elites started to lose their exclusive status. (De Luca 2)

The Second Mother brought to light diverse types of polarisations:

social polarizations (employer and employee, upper and lower classes), spatial polarizations (maid’s bedroom and guest’s bedroom, kitchen and living room, townhouse and shantytown, southern and northern), and material polarizations (cheap and expensive ice-cream, fan and air-conditioning, fine and popular dishware). (Lana 125)

These dualities echo the political polarisation of Brazil, a historical division in the country, which remains a subject of ongoing contention and shows its strong legitimacy during the 2016 crisis marked by the impeachment of the former left-wing female president, Dilma Rousseff, and the consolidation of the Parliamentary Coup: the starting point of the rise of the extreme right in Brazil in the figure of Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 (Rogero). In public discourse, the idea of the working class achieving a higher quality of life triggered considerable apprehension among upper-middle-class families. They argued that this situation would destroy their households because domestic workers might no longer be available for hire, which could in turn affect the family members’ ability to fulfil their own responsibilities effectively. It is not coincidental that the number of workers hired informally has increased (Cal and Brito). An example of the determination to maintain control over the colonial structures of servitude and resist any changes that could challenge that control (and foster marginalised groups’ restricted mobility), the former Minister of Economy, Paulo Guedes, said in early 2020, amid an economic crisis, that the dollar should not drop because “maids were going to Disneyland [in Lula’s era], a hell of a party” (Sakamoto).

The film is also included in the new socio-political vision present in Latin American cinema since the early 2000s that indicates “a collective moment in which there is recognition from filmmakers that to understand the deep, often hidden manifestations of national and social inequalities, the focus needs to shift to daily interactions inside the home” (Shaw 126). In the Brazilian context, films responding to this changing context also include Maids (Domésticas - O Filme, Fernando Meirelles and Nando Olival, 2001), Santiago (João Moreira Salles,2007), Nannies (Babás, Consuelo Lins,2010), Housemaids (Doméstica,Gabriel Mascaro,2012), Hard Labour (Trabalhar Cansa, Juliana Rojas e Marco Dutra, 2010), Neighbouring Sounds (O Som ao Redor, Kleber Mendonça Filho, 2012), and Aquarius (Kleber Mendonça Filho, 2016) (Denison; Randall; De Luca). Directed by the white middle-class director Anna Muylaert, even though her behind-the-scenes gaze captures the image of the racialised female domestic labourer, the film broadens the peripheral perspective on-screen since Val’s gaze is emphasised by the many stationary shots with the camera positioned often in the kitchen (De Luca). The film premiered in Brazil on 27 August 2015; upon release, the film reached 493,022 viewers (Ancine). Many countries purchased its exhibition rights, and it received prestigious awards, including the audience award for Best Film at Berlinale and a special jury prize for Case and Mardila in its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival (IMDb).

Restriction and Stagnation: “This Here, One Does Not Need to Have Explained, One Is Born Knowing What She Can and Can’t Do”

This section looks at different scenes of The Second Mother before Jessica’s arrival to explore how Val’s mobility is restricted and stagnated when her mobility is regulated by colonial gender and racial dynamics, which are perpetuated by myths ingrained in Brazilian culture. The film’s opening scene portrays Val’s work environment. A long still shot showcases the expansiveness of the swimming area at her employer’s house. The distant sound of construction indicates that she is isolated in protected premises. As I previously argued, the stationary camera acts as a Foucauldian panoptic mechanism (Velho 23, 217). Like the popular security cameras installed in luxurious Brazilian households, its positioning and stillness imprison Val in a permanent state of self-vigilance. Even though her employers’ eyes are not monitoring her, Val monitors “her can and cannot do”, and her mobile constraints and concessions.

Figure 1: Film’s opening scene. Swimming area at Val’s employer’s house.

The Second Mother (Que Horas Ela Volta?). Directed by Anna Muylaert. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

Fabinho wants them to swim together. Being alone, they could enjoy the sunny day, but as Val is constantly under surveillance, she refuses. As the figure of the domestic labourer is connoted by contamination and dirt, she acknowledges that the pool in her employee’s house is not a space where she can be; swimming is not an action she can perform, and wearing a swimsuit is not possible for her there. Instead, perplexed, she claims not to have a swimsuit and exclaims, “Me, swimming?” Val’s soft, tender tone towards Fabinho brings to the surface the warmth that characterises their intimate relationship. However, Val wears a white uniform, a common requirement by wealthy families for nannies to wear while on duty—a symbol of Brazilian social segregation that defines these workers’ subaltern and invisible position (Da Silva and Lira). Here, the uniform functions as a brand to mark their “cordial” relationship, encompassing both affectionate and coercive interactions. Val shares mother-and-son feelings with Fabinho, yet she is an employee, a non-member of the family, who she must serve.

The camera remains fixed to demonstrate the inertia of the situation. Val talks on the phone, insisting on speaking with her daughter, who does not want a conversation. Val’s frustration of being separated from her daughter contrasts with Fabinho’s proximity. Val holds him tenderly when he asks when his mom will return, but she does not know. The title The Second Mother appears centre framed, and the narrative direction is determined through absence and presence, distance and closeness, coldness and warmth. Drawing on the idea that the mobility of some groups can undermine or imprison the power of others (Massey), Barbara must delegate her maternal responsibilities to Val to thrive in a career; the experience of motherhood for both white Barbara and racialised Val is conditioned to emotional and spatial distance from their children.

Figure 2: Val is on the phone with Jessica while Fabinho awaits her attention.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

The following sequence depicts a time-lapse of more than ten years but indicates that everything remains the same. The house’s daily routine is still predominantly shown through a fixed camera, with long shots and slow takes, indicating a determined state of things. The house’s ample spaces, like the dining and living rooms and external area with cold, impersonal colours, remind us of a detention centre—a counterpoint to the small, claustrophobic cell that is the maid’s tiny bedroom. Capturing her confinement, Val is centre framed behind the window’s bars (13:13) of her crowded bedroom, which has a locked window and door, and where taking more than two steps is unfeasible (29:49). Much like an inmate who collects posters, letters, and gifts, the domestic labourer collects her cherished treasures: the television, the orange squeezer, the mixer, and the fan; objects lying about (like Val), awaiting a place to call home (their release). Val is restricted from movement within the home and society, seeming to live in another time and space, disconnected from technological advancements and lacking access to shared knowledge from the outside world. A notable example of this disconnect is Val’s need for assistance to use an old mobile phone and her surprise upon discovering the possibility of online registration for the university’s entrance exam.

Figure 3: Val is seen through the bars of her bedroom window.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

A hand-held camera follows Val’s backside travelling around the room while serving the guests to focus on this almost omnipresent yet still invisible figure (23:10). To Tiago De Luca,

as the camera refuses to leave the kitchen and remains in place even when the maid leaves the frame to serve her bosses or collect the dishes, it seems to echo Val’s own fixed position, her foot in the kitchen […] any attempt to cross over to “the other side” of the house, as in the scene of Barbara’s birthday party, will effectively render her invisible. (11)

De Luca argues that this scenario reveals the spatial division between employer and employee and the impossibility of social mobility for the main character. Here, I extend the concept of social mobility by incorporating Cresswell’s perspective on mobility, to the understanding that not only class defines Val’s mobile experiences but also her gender and race.

The kitchen serves as the primary space designated for domestic labour, and Val perceives herself as the one in charge of setting its rules, often referring to herself as the “owner” of the kitchen. However, despite her authority in this room, Val rarely takes the opportunity to sit down. She is constantly standing. Whenever a family member has a meal in the dining room, Val remains in the kitchen, ready to respond to any requests for assistance. Upon receiving a request, she undertakes every minor task her employers can easily handle. For example, she retrieves a can of guarana, opens it, and pours it into their glasses (08:00). At the employee’s lunchtime, Val repeats the same mechanical gestures when serving the male gardeners seated at the kitchen table (08:18). She serves the food to them and grants the request of the Black gardener who wants cassava flour. However, like her employer, the employee does not get up to pick it up. This contrast reveals that class associated with gender and racial hierarchies reflect those who can stand up and sit down and can request and do not request. A racialised female domestic labourer is not allowed to sit at the servants’ facilities, an action which is at least offered to the Black male subordinate (gardener). Val embodies the servitude and benevolence directed at the Black Mammy, revealing more mechanised forms of movement. What remains for her is to be prepared to fulfil the constant requests.

Figures 4 (above) and 5 (below): The camera remains fixed in the kitchen while Val serves soda to

her employer in the dining room and to the gardeners seated at the kitchen table, respectively.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshots.

This conflict can also be discerned within the relationship between white Barbara and racialised Val. As Cresswell argues, “[m]obility is a resource which is differentially accessed. One person’s speed is another person’s slowness. Some move in such a way that others get fixed in place” (9). Val’s slow and stagnant life contrasts with the “trendsetter” Barbara’s fast-paced and dynamic life. In a metaphor of speed and slowness, Val, who is listlessly standing, tries several times to speak with Barbara, who is vigorously running on the treadmill, about Jessica’s arrival in town: “Miss Bárbara, I needed to talk to you.” Barbara says, “Of course, did you finish the lasagne?” Val replies, “I did it, I did it, but…?” (14:15). Barbara immediately ends the conversation without listening to her. Val remains silent, yet her expressions suggest that she has more to say. After a long weekend, when she finally gets a chance to speak to Barbara, her employer asks, “Who is Jessica?” Barbara’s unfamiliarity with the name of Val’s daughter, despite Val having worked in her house for many years, underscores the contradictions between the professed love and fair treatment Val is said to receive and the neglectful treatment to which she is actually subjected by her employers.

As noted by Lúcia Sá The Second Mother’s main trope is a choreography of “the over-friendly, affectionate mode and the colder, professional, commanding mode that expects to be served” from Barbara, Carlos, and Fabinho (322). In an intimate and hierarchical distancing dialectic, “Barbara’s friendliness does not mean friendship or equality; and that being ‘almost’ part of the family means being a complete outsider” (323). In fact, Val is another functional object in the house with well-established roles. Her desires and feelings remain stagnated in the shadows.

Contestation and Rupture: “I Don’t Think I Am Better, Okay? I Just Don’t Think I Am Worse; Do You Understand?”

The final section of this article examines scenes of the film after Jessica’s arrival to analyse Val’s mobility as a more active and unrestrained experience. It highlights how she begins to subtly yet meaningfully challenge the powerful practices rooted in the prevailing gendered and racialised narratives of domesticity that had, until then, controlled her mobility. Transitioning from the stillness of the first part, upon Jessica’s arrival, the film proceeds to a sequence where Jessica disrupts an intimate familial dinner (32:29). The camera captures Jessica’s gaze at the family from a side-angle overhead shot, signalling that her viewpoint is now in the foreground. Quick cuts and brief takes break the inertia that dominated the film up to this point, speeding up its flow. Barbara, Fabinho, and Jose Carlos are depicted in close-ups to highlight their discomfort upon realising that a racialised girl from a humble background, who spent ten years separated from her mother in the countryside, shares similar aspirations with Fabinho, a privileged white boy from the metropolis.

Jessica’s goal is to take an entrance exam for the highly competitive Architecture and Urbanism programme and study at the prestigious University of São Paulo (USP), a place the “maid’s daughter” traditionally could not access in Brazil. Jessica represents the generation of inclusion empowered by the Lula era; at the time, 17% of the Brazilian working-class entered higher education compared to 8% in 2005 (“Longa”). With naturalness and confidence, Jessica occupies every corner of the residence. The camera moves, tracking Jose Carlos, Fabinho, Jessica, and Val on tour around the house (33:00). This sequence features a higher intensity of luminosity and vibrant colours compared to previous shots, evoking the enlightening influence of the girl’s ideas. Jessica accepts Jose Carlos’s invitation to spend some days as a guest in the guest room, a space Val only entered to clean. Here, Jessica dedicates most of her time to studying, sitting on a desk chair, a behaviour that Val, who is constantly on her feet working, finds quite outrageous.

Figures 6 (top left), 7 (top right), 8 (bottom left) and 9 (bottom right): In close-up shots, Barbara, Jose Carlos, and Fabinho gaze upward at Jessica with perplexed expressions on their faces, while Jessica looks firmly downward. The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshots.

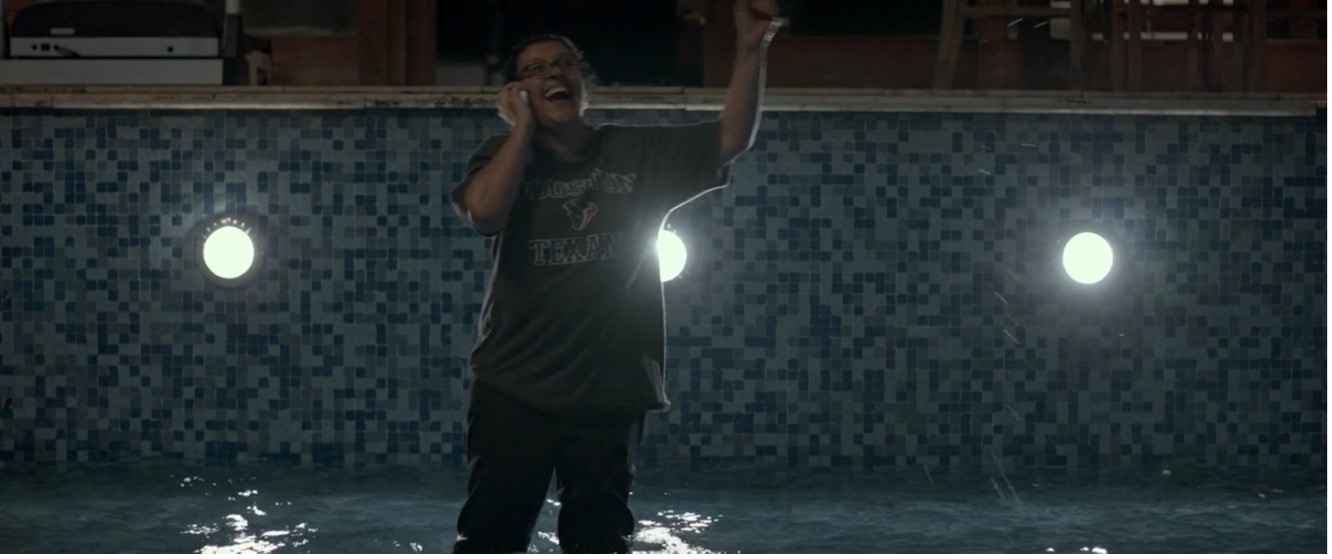

Jessica rouses annoyance as she shares her opinions on art when visiting Jose Carlos’s studio, has lunch in the dining room with the employer, and eats the expensive gourmet ice cream that “belongs” to Fabinho. Barbara contorts her face into numerous unpleasing expressions, and Val points out that her daughter sounds “cocky” and like a “know-it-all”. However, what incites the most significant uproar and dissatisfaction is Jessica’s unintentional fall into the swimming pool when Fabinho and his friend, who run around the area while she watched standing, pull her in (1:02:00). The moment unfolds in slow motion, highlighting the gushing water and their spontaneous interaction. It implies crossing the spatial class divide, representing the lower classes’ social mobility and inciting fear among the middle classes (Vazquez 39). This incident prompts Bárbara to drain the pool, claiming it was infested with rats, reinforcing the notion of contamination, attributed initially to Val but now attached to Jessica. Barbara sends Jessica to her mother’s room, and finally, the girl leaves the house.

While Jessica moves around the house putting things out of order little by little, Val’s disembodiment of the powerful practices that once restricted her mobility begins to unfold. On the morning that follows her daughter’s arrival, Val does not show up in the kitchen on time, and Barbara must cook herself breakfast (41:15). Val’s hair is messy and, instead of her usual uniform or apron, she is wearing a t-shirt, signalling a disruption in her routine. To uphold the facade of a “cordial” relationship, Barbara provides Jessica with breakfast and the fancy exclusive lemonade she enjoys (a social marker of upper-middle class) while Val does not arrive. Yet, Barbara cannot hide her irritation when she realises that the roles have reversed: the maid’s daughter is now the one being served, comfortably seated and indulging in luxurious products, while she stands and attends to her. In the following days, Val’s nervousness intensifies because of Jessica’s attitude, which leads to the doméstica breaking an expensive silver object, revealing that she can no longer perform this kind of work. Her housekeeping skills are gradually disintegrating.

Figure 10 (top left), 11 (top right), 12 (bottom left) and 13 (bottom right): Jessica occupies the employer’s house. She starts by sitting in the guest bedroom and observing an art piece in Jose Carlos’s studio. Later, she shares lunch with Jose Carlos in the dining room, where Val serves them. Finally, she’s pulled into the pool by Fabinho. The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshots.

Val is initially sceptical, but later she feels immense happiness and pride when Jessica performs well in her university entrance exams. As Jessica enters the university, Val steps into the pool. For the first time in over a decade, she occupies the pool, an ample and, up to that point, exclusive space. In a medium shot, Val is in the centre of the screen, illuminated by the pool lights as if her desires and selfhood are now in the centre of focus (1:31:50). With emotional music playing in the background, she calls out her daughter and says she loves her. Val does not swim but swings her arms and legs in the water so that her daughter can hear the soothing sounds. She gestures freely. Even though they are not physically close at that moment, Val approaches Jessica as mother and daughter both engage in the same “rebellious” act—they finally demonstrate a genuine connection after many years of their physical and symbolic distance.

Figure 14: Val stands at the center of the pool, lit up by the pool lights.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

When comparing the following two scenes, Val’s restricted mobility in the beginning of the film juxtaposes with her gradual ascent to greater and more unrestricted mobility in the second part. Initially, Val rests in the house’s outdoor area after hanging the laundry (09:22). In the twelve-second-long take, she enjoys her free minutes leaning towards the sun, enjoying the sunbathing hour (typical of the prison routine). The white tones of Val’s t-shirt and apron blend with the hanging clothes, signalling a fusion of body and domestic work function. Her life is inert, imprisoned, and her body is work. As the film draws to a close, once again Val works in the external area in the day after Fabinho has left for an exchange programme (1:36:00). Her clothes and the laundry hanging are now colourful, yet they do not match. The servitude and affection (particularly towards Fabinho) that once anchored her there no longer keeps her tied to that place. She notices the now-empty bucket, metaphorically announcing her reconfigured life.

Figure 15 (above) and 16 (below): In the film’s beginning, Val takes a break after hanging the white laundry in the house’s outdoor area. In a poignant echo, at the film’s end, Val returns to the exact location to hang colourful clothes. The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshots.

Val resigns from her job. Barbara, trying to retain her, offers a salary increase, but Val makes it clear that money is not the issue and decides to depart. As noted in the beginning of the narrative, Val is financially independent. She used to send gifts and financial support to raise her daughter and maintained no financial ties with Jessica’s father. This reflects the economic context of the Lula era, and its newfound opportunity for domestic workers to choose to leave their jobs as live-in maids. The rights granted by PEC das Domésticas EC 72/2013 and Lei Complementar 150/2015 made it possible for this group to be more confident about their entitlements and job security, paving the way for new and more optimistic life prospects and increased purchasing power (Silva, Cirilo and de Avila 178; Pezzini). Seeking different careers once they have achieved financial stability—as Val expresses her desire to enrol in a massage course—is a possibility that may not have been feasible in Brazil in the past.

The ability to sever the emotional bonds that once tied her to the employers’ household and enable her mobility is not solely reliant on the economic power Val has gained. However, this is also an important contributing factor. Initially cluttered around her small bedroom, the electronic devices Val accumulated have now been unpacked and used in her simple house in a shantytown, where she moves in with Jessica. The functionality of Val’s belongings resembles the purposes of her new bold functional life centred around herself and her daughter. On the way to their new home, the camera focuses on Val’s perspective as she gazes from inside the car out into the outside world, beyond the walls of her employer’s domestic space (1:43:03). The entire width of the avenue and the cars moving forward in six different lanes is seen in a general plan. This moment points to new pathways and fresh modes of motion now accessible to Val. She has integrated into the public sphere, which she can navigate. The car window is rolled down, allowing the wind to blow in Val’s face in a close-up view. The sun illuminates her face. Sunlight bathes her countenance, and she relishes the sun’s warmth for as long as she wants, freed from the confines of the limited patches of sunlight within the house.

Figure 17: The general shot captures the entire width of the avenue with cars moving in six lanes.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

Figure 18: Val’s face is illuminated by the sun in a close-up shot as she sits in the car.

The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

Val longs to establish both physical and emotional proximity with her daughter, much like she experienced with Fabinho over the years, and distance from the place that imprisoned her. She discovers that Jessica has left Jorge, her grandson, in the countryside and urgently requests to have him brought to São Paulo to prevent history from repeating itself. This aspiration becomes feasible as she can now reside in her own home, contemplate new employment opportunities, and allocate more free time to care for the well-being of her own family rather than that of others.

Figure 19: Val and Jessica savor coffee served in cups with mismatched colors in their new house on the outskirts. The Second Mother. Pandora Filmes, 2015. Screenshot.

In the movie’s final sequence, a notable first occurs as Val takes a seat in her kitchen (1:41:00). She does not hesitate to ask her daughter to prepare coffee for them both, savouring this moment on a Thursday afternoon. The coffee is poured into cups with mismatched colours, “black on white, white on black”, a different choice in Val’s eyes, as is her daughter a different girl. The coffee cup set was “stolen”; Val gave it to Barbara as a birthday present, despite Barbara’s disdain for it. The minor subversive act illustrates the fracture, underscores the shift from the benevolent, contaminated, and cordial Val to the one who acknowledges her own preferences and aspirations and is no longer susceptible to mistreatment. Subservience cannot bind her anymore. Val moves on.

Conclusion

Once the study of mobility considers “the fact of movement, the meanings attached to movement and the experienced practice of movement” (Cresswell, “Towards”11), examining the mobility patterns of marginalised groups, such as domestic labourers, sparks novel perspectives on acknowledging and challenging mobile dynamics entrenched in colonial, class, racial, and gender structures inside the upper-middle-class families’ homes legitimatised by Brazilian culture. In The Second Mother, there are practices of power at play in the domestic space, ensuring Val is kept in a state of stagnation. In this article, I argue that Val’s physical motion is mainly limited to repetitive actions required for household tasks, and long, motionless shots are used to reflect her lack of mobility. Val lives in her cramped, confined bedroom and maintains an inert routine predominantly in the kitchen. She appears as the Black Mammy, the symbol of contamination and dirty (Roncador). The intimate cordial relations between the employer (master) and employee (maid), dictates where and how she is allowed or not allowed to be, whether she sits or stands, serves or refuses, and accesses or is denied spaces (Holanda). These immobile experiences determine Val’s embodied role within the household, the family, and society, as Bárbara points out to Jessica: “Not past the kitchen door.”

Yet, after the arrival of Jessica, Val’s daughter, who is the product of a period characterised by the social, economic, and cultural advancement of the Brazilian working class, the impact on Val’s life is disruptive. This leads to the denaturalisation of hierarchies and a re-examination of the subtle repressions present in everyday life. Val builds new meanings and therefore extends her degree of mobility. I argue that Val’s physical movements become more dynamic and detached from household tasks. Faster shots, a travelling camera, brighter colours, and close-ups are all devices that bring the focus on Val’s self in motion. Once the self-confident young woman traverses, disputes, and regains control over the physical and symbolic spaces within the employer’s household, Val begins, simply yet meaningfully, to disembody the powerful practices that previously controlled her mobility. Val enters the pool, takes a seat, moves her body, abstains from domestic chores, quits her job, seizes command of her financial independence, aspires to a new career, and establishes a close physical and emotional connection with her daughter.

The spatial, social, emotional, and bodily mobility gained by Val, echoing the Brazilian period of empowerment for the working classes reflects gains from PEC das Domésticas EC 72/2013 and Lei Complementar 150/2015, and continues to be a source of resentment among the wealthier classes in Brazil (Rogero). Eight years after its debut, The Second Mother continues to be an indication of hope. Val’s mobility serves as a reminder of the pressing necessity to understand persistent colonial reiterations and uncovers alternative possibilities for domestic labourers in Brazil (Cal and Brito). The film steadily recognises domestic workers’ rights, ensuring that racialised female domestic labourers can continue to echo Val’s assertion: “beyond the kitchen door”.

References

1. Ancine – Agência Nacional do Cinema. “Listagem de filmes brasileiros lancados 1995 a 2019.” Observatório Brasileiro do Cinema e do Audiovisual, http://www.gov.br/ancine/pt-br/oca/cinema/arquivos-pdf/listagem-de-filmes-brasileiros-lancados-1995-a-2019.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct. 2021.

2. Cal, Danila Gentil Rodriguez, and Rosaly de Seixas Brito. “Comunicação, gênero e trabalho doméstico: das reiterações coloniais à invenção de outros possíveis.” CRV, 2020 livroaberto.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/prefix/904.

3. Costa, Fernanda. “Morte de trabalhadora doméstica por coronavírus escancara falta de políticas para proteger a classe.” Jornal da Universidade, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 16 Mar. 2020, www.ufrgs.br/jornal/morte-de-trabalhadora-domestica-por-coronavirus-escancara-falta-de-politicas-para-proteger-a-classe.

4. Cresswell, Tim. “Embodiment, Power and the Politics of Mobility: The Case of Female Tramps and Hobos.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 24, no. 2, 1999, pp. 175–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.1999.00175.x.

5. ——. “Mobilities: An Introduction.” New Formations, no. 43, 2001, pp. 9–10.

6. ——. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. Routledge, 2006.

7. ——. “Towards a Politics of Mobility.” Environment and Planning. D: Society & Space, vol. 28, no. 1, 2010, pp. 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407.

8. Da Silva, Marusa Bocafoli, and Rodrigo Anido Lira. “O uniforme branco como marca da desigualdade.” Análise Social, vol. 56, no. 2 (239), 2021, pp. 242–62. https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2021239.02.

9. De Luca, Tiago. “‘Casa Grande & Senzala’: Domestic Space and Class Conflict in Casa Grande and Que Horas Ela Volta?” Space and Subjectivity in Contemporary Brazilian Cinema, edited by Antônio Márcio da Silva and Mariana Cunha, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2017, pp. 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48267-5_12.

10. Dennison, Stephanie. “Intimacy and Cordiality in Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Aquarius.” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2018, pp. 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14701847.2018.1531226.

11. DIEESE (Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos). “Trabalho Doméstico no Brasil.” IBGE – Continuous National Household Sample Survey, www.dieese.org.br/infografico/2022/trabalhoDomestico.pdf.

12. “Longa ‘Que Horas Ela Volta?’ retrata Brasil pré-crise política.” Folha de S.Paulo, 13 Sept. 2015, www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2015/09/1681021-longa-que-horas-ela-volta-retrata-brasil-pre-crise-politica.shtml.

13. Freyre, Gilberto. Casa-grande e Senzala. U of California P, 1986.

14. Filho, Kleber Mendonça, director. Aquarius. Vitrine Filmes, 2016.

15. ——, director. Neighbouring Sounds [O Som ao Redor]. Vitrine Filmes, 2012.

16. Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Pantheon Books, 1977.

17. Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de, and G. Harvey Summ. Roots of Brazil. U of Notre Dame P, 2012.

18. IMDb. Awards, The Second Mother, www.imdb.com/title/tt3742378/awards/?ref_=tt_awd.

19. OIT – Organização Internacional do Trabalho. “Trabalho Doméstico.” www.ilo.org/brasilia/temas/trabalho-domestico/lang--pt/index.htm. Accessed 15 Nov. 2021.

20. ILO – International Labour Organization. “Who Are Domestic Workers?” www.ilo.org/global/topics/domestic-workers/who/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 11 Oct. 2021.

21. Lana, Lígia. “‘Da porta da cozinha pra lá’: gênero e mudança social no filme Que Horas ela Volta?” Rumores, vol. 10, no. 19, 2016, pp. 121–37. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-677X.rum.2016.110278.

22. Lins, Consuelo, director. Nannies [Babás]. Produced by Flávia Castro, 2010.

23. Mascaro, Gabriel, director. Housemaids [Domésticas]. Vitrine Filmes, 2012.

24. Massey, Doreen. “A Global Sense of Place.” Space, Place and Gender. U of Minnesota P, 1994.

25. Meirelles, Fernando, and Nando Olival, director. Maids [Domésticas - O Filme]. Pandora Filmes, 2001.

26. Mendes, Pedro Vítor Gadelha. “A racialização dos nordestinos em São Paulo: representações na imprensa da década de 1950 e relatos de migrantes idosos.” Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, 2021.

27. Muylaert, Anna, director. The Second Mother [Que Horas Ela Volta?]. Pandora Filmes, 2015.

28. Oliveira, Kleber Fernandes de, and Paulo de Martino Jannuzzi. “Motivos para migração no Brasil e retorno ao nordeste: padrões etários, por sexo e origem/destino.” São Paulo em Perspectiva, vol. 19, 2005, pp. 134–43.

29. Pezzini, Mario. “An Emerging Middle-Class.” OECD Yearbook 2012, vol. 2011, no. 5. www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-observer/volume-2011/issue-5_observer-v2011-5-en.

30. Pinheiro, Luana Simões, Fernanda Rezende Lira, Marcela Torres, and Natália de Oliveira Fontoura. “Os desafios do passado no trabalho doméstico do século xxi: reflexões para o caso brasileiro a partir dos dados da PNAD contínua.” Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea), 2019. repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/9538.

31. Randall, Rachel. “Cordiality and Intimacy in Contemporary Brazilian Culture: Introduction.” Journal of Iberian and Latin-American Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2018, pp. 295–310. https://doi-org.ezproxy.leidenuniv.nl/10.1080/14701847.2018.1531224.

32. Rara, Preta. Eu, Empregada Doméstica. Letramento, 2017.

33. Rogero, Tiago, host. “Os piores patrões.” Projeto Querino, season 1, episode 5, Rádio Novelo, 6 Aug. 2022. projetoquerino.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Ep-05_Os-piores-patroes_Querino-1.pdf.

34. Rojas, Juliana, and Marco Dutra, directors. Hard Labour [Trabalhar Cansa]. Dezenove Som e Imagens, 2010.

35. Roncador, Sônia. Domestic Servants in Literature and Testimony in Brazil, 1889–1999. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

36. Sá, Lúcia. “Intimacy at Work: Servant and Employer Relations in Que horas ela volta? (The Second Mother).” Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2018, pp. 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14701847.2018.1531225.

37. Sakamoto, Leonardo. “Guedes reclama de viagem de doméstica à Disney e escancara visão de país.” UOL, 12 Dec. 2020. noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/leonardo-sakamoto/2020/02/12/guedes-reclama-de-domestica-na-disney-e-prova-ser-ministro-de-bolsonaro.htm?cmpid=copiaecol.

38. Salles, João Moreira, director. Santiago. Videofilmes Produçoes Artisticas Ltda, 2007.

39. Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. O espetáculo das raças: cientistas, instituições e questão racial no Brasil. Companhia das Letras, 1993, pp. 99–133.

40. ——. “Sérgio Buarque de Holanda e essa tal de ‘Cordialidade’.” Ide, vol. 31, no. 46, 2008, pp. 83–89, pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-31062008000100015&lng=pt&nrm=iso.

41. Shaw, Deborah. “Intimacy and Distance-Domestic Servants in Latin American Women’s Cinema: La Mujer Sin Cabeza and El Niño Pez/The Fish Child.” Latin American Women Filmmakers: Production, Politics, Poetics, edited by Deborah Martin and Deborah Shaw, I. B. Tauris, 2017, pp. 123–48.

42. Silva, Camila Carvalho, Mirian dos Santos Cirilo, and Maria Cristina Alves Delgado de Ávila. “Vantagens E Desvantagens Da PEC 72/2013 - Domésticas.” Revista Científica Do UBM, no. 34, Feb. 2022, 167–88. https://doi.org/10.52397/rcubm.v0in.%2034.1273.

43. Slattery, Gram, and Rodrigo Viga Gaier. “A Brazilian Woman Caught Coronavirus on Vacation. Her Maid is Now Dead.” Reuters, 24 Mar. 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-rio-idUSKBN21B1HT.

44. Teixeira, Juliana. Trabalho Doméstico. Editora Jandaíra, 2021.

45. Turner, Graeme. Cinema como prática social. Summus Editorial, 1997.

46. Vázquez Vázquez, María Mercedes. “New Geographies of Class in Mexican and Brazilian Cinemas: Post Tenebras Lux and Que horas ela volta?” Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Resisting Neoliberalism?, edited by Claudia Sandberg and Carolina Rocha, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 65–81.

47. Velho, Francianne dos Santos. “A (i)mobilidade da doméstica brasileira nos filmes Domésticas (2001) e Que Horas Elas Volta? (2015).” MA thesis, Leiden University, The Netherlands, 2017, openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/52288.

Suggested Citation

dos Santos Velho, Francianne. “‘Beyond the Kitchen Door’: Racialised Female Domestic Labourer’s Mobility Experiences in Anna Muylaert’s The Second Mother.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 103–123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.07

Francianne dos Santos Velho is a PhD Candidate at the Centre for the Arts and Society at Leiden University. Her current research project is titled Migrant Domestic Workers in Brazil and the Netherlands: Experiences, Sensibilities, and Narratives in Visual Culture. She holds a Master of Arts in Latin American Studies from the University of Leiden, focusing on Cultural Analysis. She was also a research assistant on the HERA-funded project Night Spaces: Migration, Culture, and Integration in Europe (NL).