Stick to the Status Quo? Music and the Production of Nostalgia on Disney+

Toby Huelin

[PDF]

Abstract

This article examines the production of musical nostalgia in High School Musical: The Musical: The Series (2019–23), one of the first series created for Disney’s streaming platform. On one level, the series serves as a nostalgic extension of the High School Musical franchise in its setting and narrative construction, and a nostalgic continuation of the teen-musical genre in its idealised depiction of high-school life mediated through song. At the same time, this nostalgia is coupled with an emphasis on the show’s newness: the series transposes the original film to a new format—a self-referential, multi-episodic mockumentary—and occupies a different temporal world, in which nostalgia is technologically mediated and constructed as part of the diegesis. Focusing on music, as a primary sensory input for the evocation of nostalgia, this study explores how The Series capitalises upon this nostalgia/modernity dichotomy to structure its narrative and engender brand affinity. Drawing together textual analyses of audiovisual sequences and practitioner testimony from the show’s creatives, it demonstrates how The Series uses music to develop Disney’s brand, harnessing the technological and creative promise of the Company’s proprietary streaming service, whilst simultaneously employing nostalgic strategies to reaffirm the status quo in aspects of its narrative.

Article

With the rapid advancement of technology, our youth’s culture is constantly in a state of transformation. So often do we forget the little things that made our childhood so special and intimate. The feeling of nostalgia is one that can be so hard to replicate and yet so surreal. This feeling is something that High School Musical captures in its entirety. (Rochlin)

The evocation of nostalgia is central to the establishment of Disney+. At its launch in November 2019, the streaming platform already incorporated well-loved content from across the spectrum of Disney brands (including not only Disney but Marvel, National Geographic, Pixar, and Star Wars) and featured media dating back to the 1920s. The Disney+ subscription base massively expanded during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic—with consumers looking for reassuring “comfort” TV (Nielsen Music 25)—and reached Disney’s own five-year estimates in under a year of trading, totalling over eighty-six million subscribers by the end of 2020 (Bursztynsky). Despite recent challenges, including a steep decline in numbers of new subscribers (Sweney), Disney+ still occupies a distinctive position in the streaming landscape: its primary value lies in its ability to draw upon the Walt Disney Corporation’s vast media holdings—comprising its recent and more distant past—to elicit nostalgic emotions in its consumers and engender brand affinity; crucial components in the emergence (and sustainability) of this SVOD platform.

There are two primary ways in which Disney+ evokes nostalgic emotions in its audiences: first, through the creation of texts as “intentionally nostalgic” due to their explicit connection to pre-existing Disney media properties; and second, through the rewatching of previously created titles in a new streaming context (Pallister 2; see also Armbruster 11–12). At the launch of the service, Disney+ included two original “intentionally nostalgic” series. Both rely heavily on established franchises owned by Disney: High School Musical: The Musical: The Series (2019–2023), a mockumentary-style reboot of the original film series, and The Mandalorian (2019–), part of the Star Wars franchise. This article examines the production of musical nostalgia in the first of these shows (Fig. 1). The Series follows a group of present-day teenagers attending East High School, Salt Lake City (where the original movie was filmed), as the students mount their own production of High School Musical: The Musical. Subsequent seasons focus on productions of Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991)(Season 2), Frozen (Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, 2013) (Season 3), and High School Musical 3: Senior Year (Kenny Ortega, 2008) (Season 4), making explicit intertextual connections between The Series and the broader Disney universe.

Figure 1: High School Musical: The Musical: The Series presented within the Disney+ interface. Screenshot.

On one level, The Series serves as a nostalgic extension of the High School Musical franchise in its setting, narrative, and overall dramatic construction, and more broadly, a nostalgic continuation of the teen-musical genre in its sanitised and idealised depiction of high-school life, mediated through song. The central themes mirror the stock narrative tropes epitomised in Grease (Randal Kleiser, 1978), arguably the most famous musical set in a high school, and a nostalgic enterprise itself in its evocation of 1950s musical styles and settings. The serialised format also draws on the conventions of more recent high-school musical TV series such as Glee (2009–15). Such connections are already made explicit in the Disney+ interface, as Kyra Hunting and Jonathan Gray observe, the service “connect[s] viewers to the sprawling corporate network that is Disney through an interface that at first blush may appear similar to that of all the leading streamers, but that serves as a tightly woven net of Disney intertexts” (367). In the case of The Series, the list of suggested episodes includes a combination of newly produced Disney content (e.g., The Slumber Party (Veronica Rodriguez, 2023), World’s Best (Roshan Sethi, 2023)), the original High School Musical films (2006, 2007, and 2008), and Glee, connecting titles along the lines of genre, franchise, and context, and mixing new and pre-existing media together in the digital interface to create a deeply nostalgic viewing experience for audiences.

At the same time, this evocation of nostalgia in The Series is coupled with an emphasis on the show’s newness: this is a series which transposes the original film to a new format—a self-referential multi-episodic mockumentary—and occupies an altogether different world to the original films, in which nostalgia is now technologically mediated (e.g., through narratively significant uses of smartphones and social media) and constructed as part of the diegesis. As the series’ promotional material proclaims: “the spirit of High School Musical is back […] with new characters, new storylines, new songs, and of course, new drama” (Lin). This foregrounded tension between nostalgia and modernity in The Series thus provides an important case study for understanding the Disney brand in the twenty-first century.

Focusing on music as a primary sensory input for the evocation of nostalgia (Garrido and Davidson 32), this study explores how The Series capitalises upon this nostalgia/modernity dichotomy to structure its narrative and engender brand affinity, revealing how the relationship between the past and future is built into the show’s off-screen production processes and its on-screen narrative. The Series both uses the songs from the original High School Musical film franchise—adapted and rearranged for the new streaming context, and presented as part of the series’ own production of High School Musical: The Musical—and introduces new songs that function diegetically in the characters’ lives. Accordingly, this article examines two key musical moments that structure the first episode, and thus establish the series’ overall dramatic (and musical) tone: the new song “I Think I Kinda, You Know”, and a reimagined “Start of Something New” from the original franchise. In doing so, the research demonstrates how The Series uses music to develop the Disney brand, harnessing the technological and creative promise of the Company’s proprietary streaming service, whilst simultaneously employing nostalgic strategies to reaffirm the status quo in aspects of its narrative. Taken as a whole, the article examines the specific ways in which nostalgia is mobilised through music on Disney+ and reveals how these nostalgic processes constitute a distinctive, self-reflexive engagement with the Company’s history.

Music, Nostalgia, Disney

Nostalgia can be understood in this context as a “yearning for the past and refers to the bittersweet memories people have of past personal experiences, frequently from the period of adolescence and early adulthood” (Hans Baumgartner qtd. in Wissner 59). The term was used by physician Johannes Hofer in the seventeenth century to describe the ailments of “displaced soldiers, domestic workers and students who developed symptoms in response to their profound homesickness” (Pallister 2). The negative status of nostalgia persisted in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when it was characterised as a psychological disorder involving aspects of depression, anxiety, or psychosis (Sedikides et al. 193). In the present day, more positive formulations of nostalgia are frequently cited, in which the psychological benefits of this emotional state are often recognised. Nostalgia can, for example, foster “a stronger sense of belongingness”, “higher continuity between […] past and […] present”, and “higher levels of self-esteem and positive mood” (“What”). These positive attributes of nostalgia can be usefully capitalised upon in marketing and branding activities: as Benjamin Hartmann and Katja Brunk suggest, nostalgia is a key device for the “creation of enchantment”, or “the rendering of the ordinary into something special” (669). This is evidenced, for example, through processes of “re-enactment” that “valorize past-themed brands as tokens of a cultural condition that now appears to be superior” (677)—a trend seen in streaming media through nostalgically targeted original series (e.g., Stranger Things (2016–)), reboots (e.g., Saved By The Bell (1989–93; 2020–21)), and sequels (e.g., Gilmore Girls (2000–07) and Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life (2016)).

In the case of Disney, this trend comprises live-action remakes (e.g., The Lion King (Jon Favreau, 2019)), sequels (e.g., Mary Poppins Returns (Rob Marshall, 2018)), and serialised productions connected to pre-existing franchises (such as The Series), where the mobilisation of nostalgia is designed to maximise the commercial potential of pre-existing Disney properties.[1] The activation of nostalgia is not always positive, however: drawing upon Ryan Lizardi’s concept of “narcissistic nostalgia”, Matthew Leggatt identifies that “nostalgia, particularly when considered as an industry tool, becomes a highly conservative force. Rather than bring us closer to our past, it has a tendency to erase certain histories (often the marginal) replacing these with a […] sanitized simulacrum” (5). In the original High School Musical film series, for example, Dominic Symonds identifies the tension between its presentation of a surface-level “post-millennial, post-feminist utopia” on the one hand, and its “firmly entrenched conservative ideologies” on the other (171). He notes how the film series is “deeply committed to gender ideologies from the past”—most notably in the “rigidly demarcated way in which males and females within this school environment are ascribed activities” (i.e. sport versus academics) (173). Nevertheless, recent scholarship has recognised how Disney has used nostalgia to “correct some of the less palatable elements of its narratives” in its film remakes: for example, in the recharacterisation of Belle and the Beast in the live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast (Bill Condon, 2017), thereby creating “a considerable distance between these contemporary re-imaginings of Disney’s fairy tales and their (now dated) animated counterparts” (Mollet, Cultural History 140, 158).[2] Likewise, The Series has been “praised for its diversity and inclusion of queer teen narratives”, facilitating a more positive form of these nostalgic processes (Mollet, “I”).[3]

Central to the nostalgic work of The Series is the role of music; indeed, music is frequently cited as one of the most important sensory inputs in the evocation of nostalgia. As Sandra Garrido and Jane W. Davidson write, “just a few bars of a tune can be powerfully evocative of another time, another place, and the events and people associated with them” (32). They note, “listening to music that induces nostalgia can serve several psychological functions”, including enabling people to “reinterpret past events”, “construct identity”, and improve their mood “in times of distress” (33). Consequently, musical nostalgia can be used by brands to strengthen marketing campaigns and sell products or content to audiences. With Disney, the use of nostalgic music can be heard in, for example, the self-conscious references to previous Disney properties, such as Cinderella (Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Clyde Geronimi, 1950), in Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz’s songs for Enchanted (Kevin Lima, 2007); the interpolation of songs from the Disney Renaissance including “Part of Your World” (The Little Mermaid (John Musker and Ron Clements, 1989)) and “Beauty and the Beast” (Beauty and the Beast) into the Broadway arrangement of “Friend Like Me” (Aladdin, 2014); and the re-recording of pre-existing Disney songs for live-action remakes (e.g., Christina Aguilera’s re-recording of “Reflection” for Mulan (Niki Caro, 2020)). The activation of musical memories from one’s youth (in this case, relating to the original High School Musical film) is central to the nostalgic construction of The Series, and can be understood as participating in a broader trend mobilising millennial nostalgia in contemporary Disney properties—for example, via the aforementioned remakes of musical films from the late 1980s and 90s (The Little Mermaid, Aladdin,etc.).[4]

Important work on musical nostalgia in television has been undertaken by, among others, Reba Wissner on The Twilight Zone (1959–64) and Faye Woods on American Dreams (2002–05), in which popular music is foregrounded as part of the series’ narrative. However, the specific role of nostalgic music in the production of contemporary streaming texts has yet to be fully explored. Consequently, by centring this research around music and nostalgia in The Series, the study makes a distinctive contribution to existing scholarship, demonstrating how the use of music frequently moves beyond hearing “just a few bars of a tune” (Garrido and Davidson 32), towards long-range narrative strategies that use music to accrue meaning and build nostalgia into the fabric of episode-level musical arcs. The result is that present events in the show’s narrative can be reinterpreted through the lens of the prior High School Musical franchise, enabling Disney to solidify its brand identity on this new platform.

Studying The Series

The first season of The Series focusses on the character of Nini (Olivia Rodrigo), who is cast in the lead role of Gabriella in East High’s production of High School Musical: The Musical, and Ricky (Joshua Bassett) who has an on-off relationship with Nini and is cast opposite her as Troy. Each of the ten thirty-minute episodes takes a humorous look at a different aspect of the musical’s production process, from “The Auditions” and “The Read-Through”, to “The Tech Rehearsal” and “Opening Night”.[5] Beyond the meta-narrative at the heart of the series’ premise, numerous examples of the characters’ own nostalgia for the original film (and to a lesser extent, its two sequels) are established from the outset. For example, Carlos (Frankie A. Rodriguez), the student choreographer, defines himself as the school’s “resident High School Musical historian” and notes that he has watched the original film “thirty-seven times” (“Auditions” 07:28–07:38); Ricky is seen watching the original film on a computer to learn his audition song; and a plot point revolves around drama teacher Miss Jenn (Kate Reinders) securing Gabriella’s phone from the film to use as a prop in the school production of the show. This nostalgic reverence for the original film is heightened by numerous cameos from the original cast members, including Lucas Grabeel (Ryan), who duets with Miss Jenn in a dream sequence; Kaycee Stroh (Martha), who appears as a member of the school board; and Corbin Bleu (Chad), who directs a documentary in the third season.

In forging these close connections to the original High School Musical franchise, both in the show’s overall premise and specific narrative moments, The Series is constructed to target three overlapping audience demographics: new teen audiences discovering the High School Musical franchise on Disney+ for the first time; millennial audiences with nostalgic memories of experiencing the original franchise on the Disney Channel in the mid-2000s; and audiences who (like the characters in The Series) have performed High School Musical as their own school musical, thus creating an additional degree of identification with the characters and narrative of The Series.[6] This multifaceted approach foregrounds the concept of coviewing, with parents and children watching The Series together on Disney+, as a key marketing strategy (see Hunting and Gray 373). The Series’ simultaneous targeting of new and existing audiences is a distinctive feature of its narrative approach, with the use of music functioning as a primary device for activating feelings of nostalgia—both for audiences with memories of the original film (and its music) from their childhood and contemporary viewers encountering High School Musical for the first time on Disney+.

Whilst The Series has already attracted some critical attention, centred around its representation of nostalgia and Disney fairy tale narratives (Mollet, “I”), the precise role of music in the formation of these nostalgic processes has been less explored. Therefore, to move towards a greater understanding of musical nostalgia in The Series, this article combines textual analysis of key musical numbers and music-centred scenes with practitioner interview testimony from the show’s creatives; this second strand comprises an original interview conducted by the author with composer and songwriter Gabriel Mann, supplemented by secondary interview testimony from showrunner Tim Federle.[7] Mann composed the title music and instrumental underscore for all four seasons of The Series, and also cowrote five original songs. He had previously worked for Disney-owned projects including A Million Little Things (2018–23) and Modern Family (2009–20), the latter of which occupies a similar mockumentary style to The Series. Given his involvement throughout the full production process, Mann’s testimony offers first-hand insight relating to how nostalgia was embedded in the show’s creation.

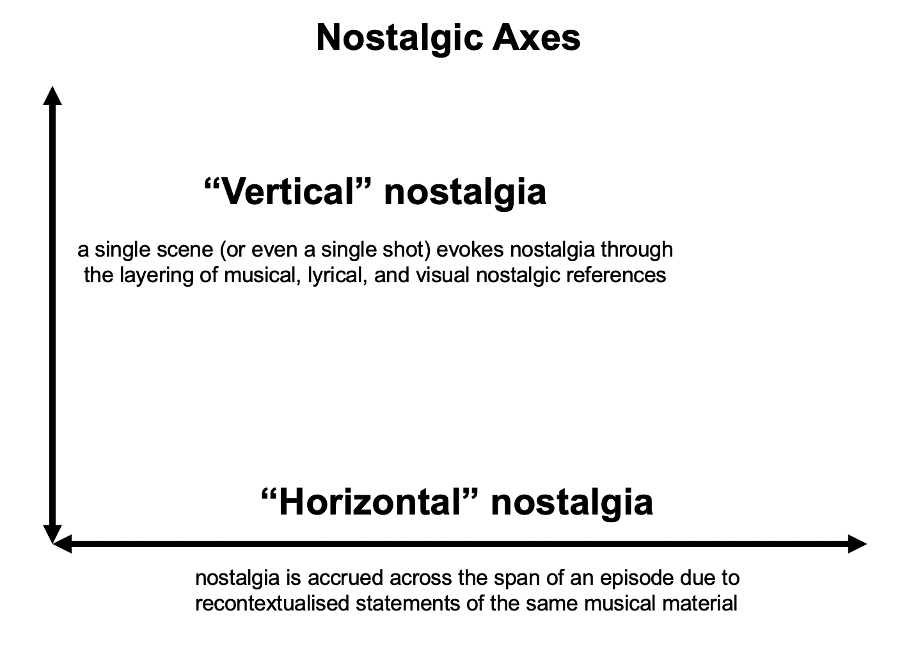

Informed by Mann’s testimony, I characterise the accumulation of nostalgia in terms of two nostalgic axes on the show (Fig. 2). Crucially, these axes are not isolated, but instead combine to create long-range, intertextual nostalgic strategies. The first axis is what I term vertical nostalgia. Louis Bayman, writing in the context of the film Pride (Matthew Warchus, 2014), discusses the notion of “temporal layering” to refer to the “potential multiplicity of temporalities within a single moment”, whereby a single scene, or even a single shot can evoke nostalgia for multiple time periods simultaneously (8). I explore an adaptation of this concept in the first episode of The Series with reference to the deployment of the original song “I Think I Kinda, You Know”. I examine how this song evokes nostalgia for the characters’ shared pasts through the construction of musical and visual nostalgic references in its presentations as part of the diegesis. Second, I extend Bayman’s analysis to encompass an additional nostalgic axis: horizontal nostalgia. This refers to the ways in which nostalgia is accrued across the span of an episode due to recontextualised statements of the same musical material, rather than through the multiple temporalities present in a single musical moment. I explore this concept with reference to the framing of a pre-existing song from the original film, “Start of Something New”. I examine how the re-presentations of this song across the span of the episode create long-range nostalgic connections to the original High School Musical film, thus placing a relationship between Disney’s past and future at the heart of The Series’ musical narrative.

Figure 2: Vertical and horizontal nostalgic axes in The Series.

“I Think I Kinda, You Know”

“I Think I Kinda, You Know” (written by Alan Zachary and Michael Weiner) is the first original song in The Series and introduces the relationship between the first season’s protagonists, Nini and Ricky. Regarding the development of these original songs (of which there are nine in the first season), Mann notes that songwriters would receive a brief from the showrunner, which would function as the “starting point”, but could then develop or change as the scene became fully formed. Importantly, Mann observes that “there was no consistent directive on the songs other than, ‘we want a great song right here’, in whatever capacity”. He notes how the new songs fulfilled an important role in “driving the sound [of the franchise] forward”, harnessing a more commercial, “poppier” sound world than the “typically musically theatrical [style]” that dominates much of the music of the original film franchise. Nevertheless, writers with musical theatre experience were still engaged to compose some of the original songs in The Series (especially in the first season). Notably, Zachary and Weiner previously wrote the music and lyrics for the Broadway musical First Date (2013–14), and, like Mann, have also worked within the broader Disney universe, writing songs for the musical episode (“The Song in Your Heart” (S06E20)) of Once Upon a Time (2011–18). Zachary and Weiner’s musical theatre background enables them to consider the narrative role of songs in The Series across the temporal span of a full episode (and beyond), rather than working in the moment-to-moment structures of pop singles. Accordingly, in the case of “I Think I Kinda”, the song features in two significant iterations within the first episode, and is central to the construction of nostalgia within Nini and Ricky’s relationship.

The first presentation of this song occurs as Nini and Ricky have been dating for approximately a year, and the song is heard in flashback. Nini has written the song and filmed herself performing it, which she uploads to Instagram. As Federle comments, “in a TikTok universe, we have a generation that puts so much content out there natively. I wanted to capture, in the first couple episodes, that spirit of music being a part of their lives. And not in a way where they’re fantasy songs, but where it’s just baked into their DNA” (qtd. in O’Keeffe). Nini overlays her recorded performance with home footage of the couple’s shared history. She has included a nostalgic black-and-white photograph and incorporates moments such as the characters playing Guitar Hero, arguably a nostalgic game, first released in 2005 (a year before the original High School Musical film). These visual nostalgic references are enhanced by the lyrical content of the song. The verse begins: “So much has happened, think of what we’ve done/In the time that the Earth has travelled ‘round the Sun”, and concludes, “Sure is every year has to come to an end/ I’d go spinnin’ ‘round the Sun with you again and again”, as Nini looks back through rose-tinted glasses on her relationship with Ricky. Musically, the sparse instrumentation features just ukulele, an instrument co-opted for similarly nostalgic pop songs, including Ingrid Michaelson’s “You and I” and Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole’s cover of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World”. Nini strums the classic four-chord pattern, with the addition of a minor chord iv in the chorus used to enhance this feeling of constructed nostalgia and wistfulness.

On one hand, this temporal layering of vertical nostalgia—the accumulation of nostalgic references in a single moment—gives Nini agency: she constructs musical, lyrical, and visual content to elicit Ricky’s nostalgic feelings so that he will tell her that he loves her, using contemporary technology (i.e. Instagram) and uploading an entire song with accompanying music video about their relationship. But crucially, this evocation of nostalgia does not work. Later, Ricky tells Nini that the Instagram video is “a really big thing to post online” and suggests that the couple “take a temporary pause” over the summer (“Auditions” 22:24–22:54). In this moment, then, the construction of nostalgia serves to reinforce the status quo of the original High School Musical series. This is a world where Nini is still defined through her relationship to the male characters, specifically Ricky, who has the agency to dismantle the temporal layering of Nini’s nostalgic construction at the conclusion of the scene. Just as Symonds writes that the original film series is “Troy’s story” (182), so this nostalgic moment puts Ricky—a character who only takes part in the school musical to save his relationship with Nini—front and centre.

In the audition sequence for East High’s production of High School Musical: The Musical, “I Think I Kinda” is heard again, constructing a form of horizontal nostalgia in its re-presentation across the episode. Ricky decides not to perform the set audition song, “Start of Something New” (from the original High School Musical film), and instead performs “I Think I Kinda” directly to Nini, in a deliberate attempt to win back her affections. There are several distinct changes from Nini’s original Instagram recording of this song: this performance is now live, unmediated through technology; Nini’s ukulele accompaniment is replaced by Ricky’s acoustic guitar; and the song features new lyrics, written by Ricky, within the narrative world of the series, to more accurately reflect his own difficulties in saying “I love you”. He rationalises that “it’s just three little words” and “it’s not a big deal”, culminating in the reflection that he does, in fact, love Nini, and can now express this to her (“Auditions” 28:42–28:48). Just as Nini’s evocation of nostalgia in the original scene was unsuccessful, however, so Ricky here also cannot use this song to earn Nini’s love. Instead, she remains unhappy with him for hijacking the audition process for his own ends, and the couple remain separated until the final episode of the season.[8]

These two presentations of “I Think I Kinda” demonstrate how nostalgia is woven into the fabric of the episode’s diegesis, as both Ricky and Nini attempt to harness the positive aspects of this emotion to mythologise their romance through song, with the ultimate goal of furthering their relationship. The fact that this construction fails in both cases demonstrates a more negative, individualised formulation of nostalgia. The focus on the characters’ present, rather than the franchise’s past, means that this form of nostalgia is ultimately less successful within the narrative world of The Series. Instead of nostalgia being evoked as a result of a pre-existing connection to the franchise (as in the example of “Start of Something New”, discussed below), the characters here construct their own forms of nostalgia around a new song, unknown to audiences until the release of this episode, which does not have the same emotional resonance as a long-range nostalgic connection to the established High School Musical brand.

“Start of Something New”

While “I Think I Kinda” is an original song composed for The Series, “Start of Something New” connects The Series directlyto the original franchise. This song is heard as the first musical number in the original High School Musical film (and therefore in the franchise as a whole), as Troy and Gabriella meet and sing karaoke at a ski resort. The status of “Something New” as a pre-existing song (i.e. available for selection on a karaoke machine’s playlist) is thus established from the outset of the franchise. In The Series, “Something New” is heard on five distinct occasions—moving from an “unheard” presentation as part of the instrumental underscore in its first iteration to a supradiegetic musical number by the end of the first episode, as the diegetic space of the school auditorium is (to borrow Guido Heldt’s framing) “transform[ed] […] into a stage” and Nini is “transform[ed] […] into a [musical-theatre] star” (137; see also Altman 67–71)— embedding musical and nostalgic links to the original film across the episode’s narrative.

The first appearance of “Something New” occurs as Nini goes to visit her grandmother. As they play cards, they discuss Nini’s opportunity to audition for the school’s upcoming production of High School Musical.Nini’s grandma counsels her on her lack of confidence in auditioning for the lead role of Gabriella. As Nini gains reassurance from her grandma, a simple instrumental rendition on solo piano of “Something New” is heard as intradiegetic underscore (“Auditions” 12:45–13:03). This type of music is defined by Ron Rodman as music that “conveys or narrates the tone, mood, or subject matter of the story”, but is not audible to the characters (56). In this context, the music has crossed over from its original diegetic presentation in the first High School Musical film, and is now built into the fabric of The Series’instrumental soundtrack. Mann notes that “occasionally Tim [Federle] would ask for [references to the songs]” to be added into the score, and that “the more important [the songs] were to the story, the more [he] would be likely to reference them.” In this case, the implied lyrics suggest the new start in Nini’s acting career and subtly evoke nostalgia for the original film series, underlining Nini’s decision to audition for the school musical which precipitates the remainder of the season’s narrative.

“Something New” is heard again three minutes later, as the song moves into the diegesis through technological mediation. Ricky has decided to also audition for the school production in an attempt to win back Nini. To prepare for his audition as Troy, he watches the “Something New” scene from the original film on a computer in one of the school’s science labs. Whilst Nini used contemporary technology to construct a nostalgic music video for “I Think I Kinda”, here, the mediation of “Something New” through quasi-retro technology is ironic. Ricky is watching this performance on a DVD, rather than viewing the title on Disney’s own streaming service. In a self-referential nod to the emergent power of Disney+, the DVD gets stuck and Ricky is extremely late for his audition because he cannot remove it from the computer. The music’s move into the diegesis combines nostalgia for the original film with a type of anti-nostalgia for its technological mediation via DVD, using music to humorously and self-reflexively imply the benefit of Disney’s new streaming platform.

Later in this episode, “Something New” is fundamental to the audition scenes; the song is now performed live in the diegetic context of the school auditorium, and is no longer heard as underscore nor mediated through digital technology. First, we witness the characters of E. J. (Matt Cornett) and Gina (Sofia Wylie) both sing their own renditions of excerpts from the song in close succession, intercut with Ricky running to the audition. Then, the audition sequence (and episode as a whole) culminates in Nini’s audition. Nini’s rendition begins a cappella, and then continues with simple piano accompaniment, during a power cut in the school auditorium. A prominent cymbal crash leads into the prechorus, with the addition of a lyrical string ensemble to the instrumentation. Dramatic wind chimes before the chorus facilitate an audio dissolve—“a passage from the diegetic track […] to the music track (e.g., orchestral accompaniment) through the intermediary of diegetic music” (Altman 63)—through which the song reaches its climax. Nini is transformed: now wearing Gabriella’s iconic red dress from the (end of the) original film with full orchestration and evocative stage lighting, the song morphs into a supradiegetic musical number. As Heldt identifies, this occurs when the audio dissolve is matched by the “transformation of a realistic diegetic space […] into the ideal space of a faraway time or land or dream; and the transformation of a character into a hidden self that can only come out in musical performance” (137). The audience witnesses Nini’s self-confidence visibly increase as she continues to sing, reaching a triumphant climax in the song’s final moments. Richard Dyer has characterised such musical numbers as creating feelings of “utopianism” in musical theatre, offering “something we want deeply that our day-to-day lives don’t provide” (20). But, importantly, Nini is still denied agency in this moment: she can only transcend reality through singing a song which is not hers—it is a pre-existing song and originally enters the diegesis bonded to Ricky (via the technological context of watching the original film on DVD), rather than Nini. In addition, this transcendent, utopian moment is only fleeting: the scene abruptly returns to the ordinary world of the school auditorium as Nini delivers the final line, and her “day-to-day” reality returns (Dyer 20).

The deployment of “Something New” across the span of this episode demonstrates how horizontal nostalgia can function not just through the mere suggestion of a melody or lyric, but through imbuing the entirety of an episode with references to this song across different diegetic levels, culminating in Nini’s final performance. On one level, this long-range nostalgic strategy promotes audience engagement: the extensive musical connections to the original High School Musical films prime viewers to identify where and how these pre-existing songs will be reappropriated to new dramatic ends in The Series (e.g., as subtle underscore or viewed on TV), thus creating positive nostalgic feelings for the High School Musical brand, enhanced by the layering of visual and narrative references to the original films. At the same time, however, the instances of “Something New” within the episode’s diegesis—both the unsuccessful use of retro technology (the High School Musical DVD), and the sudden return to reality at the end of Nini’s audition performance of “Something New”—mirror the more negative nostalgic formulations of “I Think I Kinda” within The Series’ narrative construction, and foreground the impossibility of returning to an idealised, nostalgically remembered past.

Conclusions

This article has examined the ways in which the construction of musical nostalgia is central to the narrative work of The Series, through its use of both pre-existing and original songs. In establishing an original, bipartite framework for the analysis of nostalgia, which could be productively applied to other texts within the Disney universe (and beyond), it has advanced two main arguments. First, it has shown how long-range forms of musical nostalgia can provide latent meaning that directly impacts upon The Series’ narrative. Within the context of Disney+, this evocation of nostalgia is vital to continued brand familiarity and engagement; music thus fulfils an important role in connecting the new streaming interface (and its new content) to the prior High School Musical franchise, and by extension, to Disney’s history. Second, on the surface, these kinds of nostalgia present a forward-looking vision: in “I Think I Kinda”, nostalgia is mediated through technology and Nini is initially given greater narrative agency than Gabriella in the original franchise in her self-conscious construction of the nostalgic video. Likewise, in “Something New”, the recontextualisation of the song across the diegesis arguably calls attention to the artifice of its dramatic construction. At the same time, however, the fact that these nostalgic evocations are often unsuccessful—either through frustrated relationships (Nini and Ricky in “I Think I Kinda”) or uses of outdated technology (the High School Musical DVD in “Something New”)—presents a more knowing, less idealistic formulation of nostalgia.

Disney’s contemporary construction of nostalgia for the High School Musical franchiseextends into the real world (a third nostalgic axis, perhaps) in the original Disney+ reality series Encore! (2019–20), which reunites high-school alumni to recreate their childhood performances. One of the chosen musicals is High School Musical, thus adding additional layers of paratextual meaning in relation to notions of lived nostalgia as these adults look back on their childhood. As one participant comments, “I moved to New York City and I performed, but now […] it’s on the back burner”, as the intertitles note that the performers get “the chance […] to do it all again” (“Encore!”0:49–1:05).[9] Like the uses of music in The Series, Encore! arguably offers a more knowing vision of the dangers of rose-tinted nostalgia, in highlighting how the participants’ lived reality differs from their childhood expectations and unfulfilled aspirations of a utopian future. Considered more broadly, whilst the marketing materials for Disney+ foreground nostalgic “comfort TV”—as a way of exploiting the commercial potential of the Company’s extensive pre-existing media properties—these extensions of the High School Musical franchise demonstrate a less straightforward version of nostalgia, in which a more critical relationship between Disney’s past and present emerges. Whilst such a relationship may not be immediately generalisable to other streaming platforms, given the Company’s vast back catalogue and the interconnectedness of its titles in the Disney+ interface, the arguments advanced herein nevertheless provide an important window for understanding evolving nostalgic processes—as constructed through music—in contemporary streaming media. These processes serve, to a degree, to undercut the “magical experience” of Disney content (Bryman 109), instead connecting The Series to the real world and offering a more contemporary, self-reflexive engagement with Disney’s past.This more negative vision of nostalgia in The Series is striking when viewed within the current context of Disney’s 100th anniversary celebrations, where the promotional materials emphasise tradition, and foreground the continuation of “the greatest stories” passed “from one generation […] to the next” (“Disney 100” 00:38–00:56), as facilitated through the curated “Disney 100 Collection” within the Disney+ interface. By contrast, both The Series and Encore! demonstrate a more complex and nuanced relationship between the utopian nostalgia that is promoted as central to remembering Disney’s past, and the more realistic visions that mark the continuations of the High School Musical franchise, and which are embedded into The Series’ production. As Mann comments, “as soon as you get into nostalgia, you’re not present in the show […]. It’s […] something you’re putting onto the show that has nothing to do with the show” (2023). In this sense, The Series demonstrates the need to engage fully with the present, rather than a misremembered, nostalgic past, and thus provides a new angle for understanding the relationship between nostalgia and the Disney brand as it enters its second century.

Acknowledgements

Early versions of this research were presented at the genre/nostalgia conference (University of Hertfordshire, 2021), and the annual conference of the British Association of Film, Television and Screen Studies (University of Southampton, 2021). I am grateful to colleagues at both events for their questions. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Notes

[1] This activation of nostalgia can be traced back to (at least) the founding of Disneyland in 1955: Walt Disney proclaimed the theme park as a place where “the older generation [could] recapture the nostalgia of days gone by” (qtd. in Bryman 21), as demonstrated in the “harking back to turn-of-the-century middle America” on Main Street USA, or the “cinematic mould” of the Wild West in Frontierland (21).

[2] Mollet identifies how the original Beauty and the Beast animated feature “has been criticised for effectively validating an abusive storyline” in the relationship between Belle and the Beast, whereas in the contemporary remake, the couple “forge a more emotionally complex connection” in which the Beast’s “intellectual suitability as a partner for Belle” is foregrounded (Cultural History 155, 153).

[3] The Series won the 2020 GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Kids and Family Programming in recognition of its inclusion of gay and bisexual characters: for example, Carlos and Seb begin a relationship in the first season; Nini has same-sex parents; and Ashlyn and Big Red both come out as bisexual (Season 3).

[4] Part of this trend comprises the construction of (musical) nostalgia for specific Disney Channel properties (such as High School Musical). The “Throwback Thursday” strand of the Disney Channel’s YouTube account, for example, presents compilations of 2000s theme songs as a way of driving engagement among millennial audiences.

[5] This article takes The Series’ first season as its primary object of analysis, given that this is where the connections to the original High School Musical franchise are established and rendered most explicit.

[6] The real stage musical available for licensing by schools is entitled High School Musical on Stage!, not High School Musical: The Musical, thus adding another layer of construction to The Series’ narrative.

[7] This interview with Mann was conducted on 3 Dec. 2023 via Zoom. Other production personnel were contacted for interview but did not respond within this project’s timeframe. Federle’s testimony is quoted in O’Keeffe.

[8] These problems in their relationship are borne out as The Series progresses: Nini is gradually written out of the show (due in large part to Rodrigo’s escalating pop-music career), and Ricky begins a new relationship with Gina, initially established as Nini’s musical-theatre rival.

[9] In an example of Disney+’s tightly controlled branding practices, Encore! was removed from the service in May 2023, alongside around sixty other titles (Palmer 2023).

References

1. Aguilera, Christina. “Reflection.” Mulan: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney Records, 2020.

2. Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical. Indiana UP, 1987.

3. American Dreams. Created by Jonathan Prince, NBC Studios, 2002–2005.

4. Armbruster, Stefanie. Watching Nostalgia: An Analysis of Nostalgic Television Fiction and Its Reception. Transcript, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839435090.

5. “The Auditions.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, Season 1, Episode 1, 12 Nov. 2019, Disney+, https://www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/video/bed7ee1f-d476-4ca9-8f18-19b07fd4d4eb.

6. Bassett, Joshua, and Olivia Rodrigo. “I Think I Kinda, You Know.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series: The Soundtrack, Walt Disney Records, 2020.

7. Bayman, Louis. “Can There Be a Progressive Nostalgia? Layering Time in Pride’s Retro-Heritage.” Open Library of Humanities, vol. 5, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1–29. https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.324.

8. Beauty and the Beast. Directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1991.

9. Beauty and the Beast. Directed by Bill Condon, Walt Disney Pictures, 2017.

10. Beguelin, Chad, et al. Aladdin. Directed by Casey Nicholaw, performance by Adam Jacobs et al., 2014–present, New Amsterdam Theatre, New York City.

11. Benson, Jodi. “Part of Your World.” The Little Mermaid: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney Records, 1989.

12. Bryman, Alan. The Disneyization of Society. SAGE, 2004. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446220122.

13. Bursztynsky, Jessica. “Disney+ Emerges as an Early Winner of Streaming Wars, Expects up to 260 Million Subscribers by 2024.” CNBC, 11 Dec. 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/11/after-showing-massive-growth-disney-hikes-5-year-subscriber-goal-.html.

14. Cinderella. Directed by Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Clyde Geronimi, Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1950.

15. “Disney 100 Years Super Bowl Commercial.” Uploaded by Inside the Magic, YouTube, 13 Feb. 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPK_JIM6Hi0.

16. Dyer, Richard. Only Entertainment. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2002.

17. Enchanted. Directed by Kevin Lima, Walt Disney Pictures, 2007.

18. Encore! Created by Jason Cohen, Disney+, 2019–2020.

19. “Encore! Official Trailer. Disney+” Disney Plus, YouTube, 24 Aug. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgR3DLLm_j4.

20. Frozen. Directed by Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2013.

21. Garrido, Sandra, and Jane W. Davidson. Music, Nostalgia and Memory: Historical and Psychological Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02556-4.

22. Gilmore Girls. Created by Amy Sherman-Palladino, Warner Bros. Television, 2000–2007.

23. Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life. Created by Amy Sherman-Palladino, Warner Bros. Television, 2016.

24. Glee. Created by Ryan Murphy, Brad Falchuk, and Ian Brennan,Twentieth Century Fox Television, 2009–2015.

25. Grease. Directed by Randal Kleiser, Paramount Pictures, 1978.

26. Guitar Hero. Directed by Greg LoPiccolo, Harmonix/RedOctane, 2005. PlayStation 2 game.

27. Hartmann, Benjamin J., and Katja H. Brunk. “Nostalgia Marketing and (Re-)enchantment.” International Journal of Research in Marketing, vol. 36, no. 4, 2019, pp. 669–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.05.002.

28. Heldt, Guido. Music and Levels of Narration in Film.Intellect, 2013. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_625671.

29. High School Musical. Directed by Kenny Ortega. Disney Channel, 2006.

30. High School Musical 2. Directed by Kenny Ortega. Disney Channel, 2007.

31. High School Musical 3: Senior Year. Directed by Kenny Ortega. Disney Channel, 2008.

32. High School Musical: The Musical: The Series. Created by Tim Federle, Disney Channel, 2019–2023.

33. Hunting, Kyra, and Jonathan Gray. “Disney+: Imagining Industrial Intertextuality.” From Networks to Netflix: A Guide to Changing Channels, edited by Derek Johnson, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2023, pp. 367–76. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003099499-38.

34. Iglehart, James Monroe, et al. “Friend Like Me.” Aladdin: Original Broadway Cast Recording, Walt Disney Records, 2014.

35. Johnson, Derek, editor. From Networks to Netflix: A Guide to Changing Channels. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003099499.

36. Kamakawiwo‘ole, Israel. “Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World.” Facing Future, Mountain Apple, 1993.

37. Lansbury, Angela. “Beauty and the Beast.” Beauty and the Beast: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney Records, 1991.

38. Leggatt, Matthew, editor. Was It Yesterday? Nostalgia in Contemporary Film and Television. SUNY Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781438483504.

39. The Lion King. Directed by Jon Favreau, Walt Disney Motion Pictures, 2019.40. The Little Mermaid. Directed by John Musker and Ron Clements, Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1989.

41. Lin, Kelly. “Get to Know High School Musical: The Musical: The Series!” Disney News, 31 Oct. 2019, https://news.disney.com/get-to-know-high-school-musical-series.

42. Lizardi, Ryan. Mediated Nostalgia: Individual Memory and Contemporary Mass Media. Lexington Books, 2015.

43. The Mandalorian. Created by Jon Favreau, Lucasfilm, 2019–present.

44. Mann, Gabriel. Zoom interview. Conducted by Toby Huelin, 3 Dec. 2023.

45. Mary Poppins Returns. Directed by Rob Marshall, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2018.

46. Michaelson, Ingrid. “You and I.” Be OK, Cabin 24, 2008.

47. A Million Little Things. Created by DJ Nash, ABC Signature, 2018–2023.

48. Modern Family. Created by Christopher Lloyd and Steven Levitan, Twentieth Century Fox Television, 2009–2020.

49. Mollet, Tracey. A Cultural History of the Disney Fairy Tale: Once Upon an American Dream. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50149-5.

50. ——. “‘I Guess I Just Don’t Feel Like a Natural Belle [...] and Sometimes that Feels Complicated...’: High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, Disney Fairy Tales, Nostalgia and Authenticity.” Disney, Culture and Society Research Network Annual Conference, online, 26 June 2023.

51. Mulan. Directed by Niki Caro, Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2020.

52. Nielsen Music. “COVID-19: Tracking the Impact on the Entertainment Landscape.” Nielsen Music, 8 Apr. 2020, static.billboard.com/files/2020/04/COVID-19-Entertainment-Tracker-Release-1-1586793733.pdf.

53. O’Keeffe, Kevin. “High School Musical: The Musical: The Series Creator Talks Inspiration, Punctuation and More.” Primetimer, 7 Nov. 2019, www.primetimer.com/quickhits/high-school-musical-the-musical-the-series-showrunner-tim-federle-talks-disney-series-punctuation-and-a-male-sharpay.

54. Once Upon a Time. Created by Edward Kitsis and Adam Horowitz, ABC Studios, 2011–2018.

55. “Opening Night.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, Season 1, Episode 9, 3 Jan. 2020, Disney+, www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/play/649f5c1c-119f-4733-91c7-77c4955cab1b.

56. Pallister, Kathryn, editor. Netflix Nostalgia: Streaming the Past on Demand. Lexington, 2019.

57. Palmer, Roger. “Industry Insider Explains Why Disney+ Is Removing Original Content.” What’s on Disney Plus, 25 May 2023, whatsondisneyplus.com/industry-insider-explains-why-disney-is-removing-original-content.

58. Pride. Directed by Matthew Warchus, Twentieth Century Fox, 2014.

59. “The Read-Through.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, Season 1, Episode 2, 15 Nov. 2019, Disney+, www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/play/613f35e1-6d51-4c1c-bb7b-f5e14322a947.

60. Rochlin, Steven. “Review of High School Musical (2006).” Google Reviews, 2019, www.google.com/search?q=high+school+musical+reviews. Accessed 29 Nov. 2023.

61. Rodman, Ron. Tuning In: American Narrative Television Music. Oxford UP, 2010.

62. Rodosthenous, George, editor. The Disney Musical on Stage and Screen: Critical Approaches from Snow White to Frozen. Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474234207.

63. Rodrigo, Olivia. “Start of Something New.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series: The Soundtrack, Walt Disney Records, 2020.

64. Saved by the Bell. Created by Sam Bobrick, NBC Productions, 1989–1993.

65. Saved by the Bell. Created by Sam Bobrick, Universal Television, 2020–2021.

66. Sedikides, Constantine, et al., “To Nostalgize: Mixing Memory with Affect and Desire.” Advances in Experimental Psychology, vol. 51, 2015, pp. 189–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2014.10.001.

67. The Slumber Party. Directed by Veronica Rodriguez, Disney Channel, 2023.

68. “The Song in Your Heart.” Once Upon a Time, Season 6, Episode 20, 7 May 2017, ABC.

69. Stranger Things. Created by The Duffer Brothers, 21 Laps Entertainment, 2016–present.

70. Sweney, Mark. “Global Giants Gear Up to Build Streaming Model 2.0.” The Guardian, 30 Dec. 2023, www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/dec/30/global-giants-gear-up-to-build-streaming-model-20.

71. Symonds, Dominic. “‘We’re All in This Together’: Being Girls and Boys in High School Musical (2006).” The Disney Musical on Stage and Screen: Critical Approaches from Snow White to Frozen,edited by George Rodosthenous, Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2017, pp. 169–84. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474234207.ch-010.

72. “The Tech Rehearsal.” High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, Season 1, Episode 8, 27 Dec. 2019, Disney+, www.disneyplus.com/en-gb/play/460b2d41-352e-43c4-8cbd-d9155b0f9896.

73. The Twilight Zone. Created by Rod Serling, CBS Productions, 1959–1964.

74. “What Nostalgia Is and What It Does”. Nostalgia Research Group, University of Southampton, UK,2023, www.southampton.ac.uk/nostalgia/what-nostalgia-is.page. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.75. Winsberg, Austin, et al. First Date. Directed by Bill Berry, performance by Zachary Levi et al., 2013–2014, Longacre Theatre, New York City.

76. Wissner, Reba A. “No Time Like the Past: Hearing Nostalgia in The Twilight Zone.” Journal of Popular Television, vol. 6, no. 1, 2018, pp. 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1.

77. Woods, Faye. “Nostalgia, Music and the Television Past Revisited in American Dreams.” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, vol. 2, no. 1, 2008, pp. 27–50. https://doi.org/10.3828/msmi.2.1.3.

78. World’s Best. Directed by Roshan Sethi, Walt Disney Pictures, 2023.

Suggested Citation

Huelin, Toby. “Stick to the Status Quo? Music and the Production of Nostalgia on Disney+.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 27, 2024, pp. 58–74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.27.06

Toby Huelin is a musicologist and media composer based at the University of Leeds, where he holds the positions of Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Arts and Humanities Research Institute and Teaching Fellow in Film Music in the School of Music. Toby is the author of journal articles for Music and the Moving Image, Critical Studies in Television, and the European Journal of American Culture, and has contributed chapters to edited volumes (Routledge, Palgrave Macmillan). He recently coauthored a chapter on Disney film music for The Frozen Phenomenon (Bloomsbury, forthcoming).