Part of Whose World? How The Little Mermaid (2023) Attempts to Revise the Racist Tropes of the 1989 Animated Film Musical

Niall Richardson

[PDF]

Abstract

The Little Mermaid (1989) has been the subject of much critical discussion but there has been little attention paid to its representation of race. Utilising textual analysis and drawing upon relevant critical paradigms from Disney studies and scholarship of film musicals, this article argues that The Little Mermaid was an implicitly racist narrative. Through analysis of the musical sequences this article shows how The Little Mermaid created a dichotomy between an exclusively white land life that is coded as superior to multiethnic Mer life. While white society on land is represented as postindustrial, well ordered and crime free, the multiethnic culture under the sea is coded not only as sexually unbridled, where promiscuous fish all “get the urge and start to play” with each other’s bodies, but as a thoroughly corrupt society racked with Welfare Queen coded villainesses dealing in black magic. The article contends that the 2023 remake attempts to revise many of the racist tropes of the original song sequences but, in its depiction of a society in which racial difference is devoid of socio-political significance, The Little Mermaid (2023)—especially in its Berkeley inspired dance sequences—reduces racial difference to a mere aesthetic of colour.

Article

Often identified as the genesis of the Disney Renaissance, The Little Mermaid (John Musker and Ron Clements, 1989) was the company’s first box office hit after a succession of flops. The studio’s previous release, The Black Cauldron (Ted Berman and Richard Rich, 1985), for example, had been a box office disaster and “nearly bankrupted the company” (Byrne and McQuillan 27). A retelling of the Hans Christian Anderson story as an animated musical, The Little Mermaid narrates how Ariel, a sixteen-year-old, headstrong mermaid, becomes enchanted with life on land and falls in love with a human—Prince Eric. Ariel’s father, King Triton, forbids her from having any contact with land society and so Ariel makes a deal with a sea witch, Ursula, in which she exchanges her voice in return for a magic spell that transforms her tail into legs. Ariel then has three days to make Eric fall in love with her, signified by a heartfelt kiss, or else she will return to her mermaid form and be Ursula’s prisoner. After overcoming various obstacles, such as Ursula masquerading as the human Vanessa and bewitching Eric, Ariel does secure the love of her prince and, in classic Disney style, the pair are married in a white wedding ceremony.

A commercial and critical success, which “marked the rebirth of the Disney Corporation as one of the largest multinationals in America” (Zarranz 56), The Little Mermaid was also the first animated musical to bring the talents of composer Alan Menken and lyricist Howard Ashman to the Disney franchise. The film has been the subject of extensive analyses with critics discussing how it was the first Disney animated musical to utilise Broadway performance style (Bunch; Kunze); how it revised both the narrative and ideology of the Anderson tale (Bendix; Trites); how it supports “ideologies of compulsory able-bodiedness” (Sebring and Greenhill 257) and how it may be read as an allegory for gender transition (Hurley; Spencer). Understandably, most of the criticism of The Little Mermaid (and of Disney princess narratives more generally) has addressed the film’s representation of femininity with critics debating how the film either reinforces or challenges stereotypes of women (Bell; Davis, Good Girls; Do Rozario; O’Brien; Tseëlon; White). These discussions have ranged from analyses of how Ariel, through her desire to consume goods produced on land, can be read as a postfeminist heroine (Frasl; Stover) through to critiques inspired by Butlerian positions about how the narrative (especially the inclusion of the drag-appearing villain Ursula) can be seen to deconstruct essentialist ideas of gender (Sells).

However, relatively little analysis has focused on the film’s representation of race. The exceptions are Amy Davis (Good Girls, 180), who emphasises that life on land is represented as exclusively white, and Patrick Murphy, who argues that this land/sea dichotomy suggests a colonialist ideology in how human world is coded as postindustrial, while aquatic life is represented as underdeveloped, in which the Merpeople merely sing and dance to Calypso all day. Given that the ambassador of this under the sea lifestyle is the Jamaican coded crab, Sebastian, it is fair to read the Merpeople as representing “Caribbean and other equatorial peoples” (Murphy 132) or indeed developing nations generally (Davis, Good Girls 180).This article seeks to develop Davis’s and Murphy’s analyses by focusing on how The Little Mermaid can be read as a racist text. Through analysis of the key musical sequences, this article will show how The Little Mermaid represents a land life that is coded as postindustrial and exclusively white but, most importantly, sexually reserved. By contrast, sea life is not only represented as multiethnic but as riddled with black market crime and sexually unbridled. The Little Mermaid can even be seen as the genesis of the Disney motif of representing “white characters as more demure and conservative” while conflating the characters of colour (especially women) “with the exotic and sexual” (Lacroix 222). In representing Ariel as determined to flee Mer society to be part of life on land, the film legitimates a white supremacist narrative in which (white) land society is deemed preferable and superior to multiethnic Mer life.

“Down in the Muck Here”: Orgiastic Frenzy “Under the Sea”

In the much beloved “I want” song—“Part of That World”—Ariel explains how she longs to ascend to life on land. [1] According to Ariel, this culture is superior to Mer life because it makes such “wonderful things” and, in her naïve view (unsupported by empirical evidence), offers a more egalitarian society in which parents do not “reprimand their daughters” for their inquisitiveness about other cultures. This hierarchy, in which land society is coded as superior is supported through the cinematography of “Part of that World”, in which the camera either positions the spectator as looking down on Ariel via a high angle shot or else as offering her point of view—gazing at elevated life above sea (Sells 178).

A couple of scenes later, Sebastian tries to persuade Ariel that aquatic life is “better than anything they have up there.” Sebastian’s “Under the Sea” number is certainly very persuasive. It is the showstopper of the film (Whitley 42); its lyrics celebrate the multicultural, pleasure-oriented life of the Merpeople and, most relevant for the genre of the film musical, evokes the feeling of utopia that Richard Dyer argues is the key pleasure of musicals. According to Dyer, musicals give a sense not of how utopia looks but of how it feels. In the vibrant song-and-dance sequences, everyday experiences of boredom, lethargy and loneliness are replaced by feelings of excitement, vitality and community (Only 25–28). Yet, although “Under the Sea”, with its infectious calypso rhythms and dynamic choreography, does indeed make the spectator experience the joy of utopia—and a sense that life in the ocean is fabulous—the sequence utilises stereotyped, racist iconography in its depiction of the fish and conflates this racial diversity with sexual impropriety and even nonconsensual promiscuity.

“Under the Sea” reinforces tropes of race often found within film musicals given that many of the fish are represented through racial stereotypes. Sebastian not only speaks with an exaggerated Jamaican accent but has grossly caricatured lips while the Fluke is identified as “the Duke of Soul” and has the iconography often associated in popular culture with Black, heroin-addicted jazz musicians. Another fish, with her exaggerated, colourful head attire, is a reference to Carmen Miranda—especially her iconic role as the Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat in The Gang’s All Here (Busby Berkeley, 1943). Although Miranda was Portuguese, she was coded in her film roles as a sexy Brazilian whose performances can be read as supporting racist tropes of primitivism and Latina hypersexuality.[2] Finally, one of the fish is simply called “The Black Fish” and has facial features reminiscent of blackface minstrelsy—the entertainment spectacle (developed in the nineteenth century) in which white actors wore blackface makeup to caricature the iconography and racial stereotypes of Black Americans.

Not only are the fish represented as racial stereotypes (even caricatures) but the “Under the Sea” sequence functions as the narrative conceit that Dyer has labelled “the colour of entertainment” (Only 36), in which characters of colour feature in musicals only as entertainers—their sole purpose being to sing and dance for the amusement of the other white characters (in this scene, Ariel) who function as the point of focalisation for the spectator. Dyer explains that although white characters also sing and dance in musicals, their performances function in a different way from characters of colour. First, white characters’ singing, reveals further character development—especially in their “I want” arias where they sing about their desires and ambitions. Second, white characters’ dancing enables them to command the space—further colonising these areas through their dance (40). By contrast, when characters of colour sing and dance, they are merely performing for the entertainment of the white onlookers and are confined simply to one location (89).

“Under the Sea” not only furthers the trope of characters of colour represented as racial stereotypes and mere entertainers but is, for a children’s film, a very sexually suggestive song sequence. This is due to its innuendoes (“Darling it’s better, Down where it’s wetter”) but also in how its aesthetics reference one of the most risqué of all film musicals’ choreographers: the great Busby Berkeley (Bell 114; Do Rozario 48).

Although Berkeley is celebrated for being the most cinematic of choreographers (Robbins; Rubin), because he used his camera to create the illusion of dance from a group of chorines who were merely making poses, Berkeley’s choreography has also been criticised for the way it facilitated voyeurism of objectified female bodies (Rubin 70; Fischer 5; see also Delamater; Mellencamp; Rabinowitz) and, most relevant for the analysis of “Under The Sea”, coded dancers as sexually free and available. For example, in Berkeley’s “I’m Young and Healthy” from 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933), the lead male, Billy Lawler (played by Dick Powell), serenades a revolving platform of chorines (all attired in the suggestive outfit of furry hot pants) explaining that because he is “young and healthy” and “full of vitamin A” it would be “a shame” not to have all of these women in his arms. His song is not delivered to one woman but to the revolving platform of similar looking chorines thus suggesting that all these women are sexually available to him. However, as is characteristic of Berkeley, these medium shots of the chorines are then replaced with extreme high angle shots (Berkeley often joked that he needed to go through the roof to get the camera high enough) which abstract the women’s bodies into surreal, flower-like, kaleidoscopic patterns (Rubin 6). In this respect, Berkeley not only used the camera as a way of investigating and fragmenting the female body, so that the women would simply become another prop, but this technique of cinematographic abstraction masked the voyeurism and innuendo of Berkeley’s choreography. Given that the sequences represented the women’s identities as “completely consumed in the creation of an overall abstract design” (Fischer 5) in which a body is merely “a decorative or deindividualized part of a larger arrangement” (Rubin 70), the cinematography obscured the sexual suggestiveness of his sequences—especially how the dancers were coded as sexually accessible. Therefore, when the 42nd Street sequence concludes by having the camera track through the chorines’ open legs—a Berkeley motif labelled as “crotch shots” (Altman 217–23), the choreographic equivalent of contemporary upskirting—because this action is performed on dancers that have already been transformed into abstract, kaleidoscopic patterns, the spectator may not even be aware of how this camera movement implies sexual penetration of freely available bodies (Fischer 3).

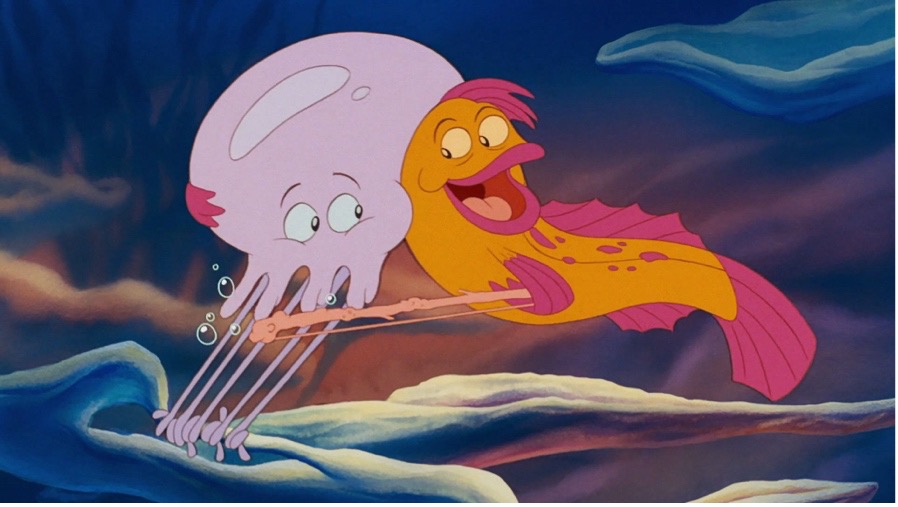

“Under the Sea” may feature anthropomorphised fish to “take the place of women in Ashman/Menken Berkeley-esque numbers, but the spirit of display remains” (Bell, 114). Like the Berkeley sequences, it commences with a representation of living (albeit in this case, animated) bodies which then metamorphose into abstract, kaleidoscopic patterns. The final sequence of “Under the Sea” is a fast montage which represents a whirl of indistinguishable shapes, in a flurry of vibrant colours, as the fish gyrate and dance freely together. Yet, where “Under the Sea” is most representative of Berkeley’s ideology is in its coding of the dancers (like the Berkeley chorines) as sexually available and promiscuous. Sebastian sings of how the fish all “get the urge and start to play” while the camera then shows fish playing with each other’s bodies and making music from each other’s body parts. This not only references the euphemism for sex—making sweet music together—but suggests sexual promiscuity. It is obvious that the fish not only get the urge to play with a random sexual partner but, after they have finished with one body, simply move onto another.

Figure 1: The promiscuous fish get “the urge and start to play” with each other’s bodies. The Little Mermaid, 1989. Dir. John Musker and Ron Clements, Walt Disney Studios. Screenshot.

This orgiastic dance is not merely celebrating sexual freedom but demonstrates a disregard for consent. Ariel’s friend Flounder (who is coded as being very young, perhaps even a tween) is swimming through this orgy, looking for Ariel, when the Carmen Miranda fish lassoes him and grinds her buttocks against him. It is obvious from the expression on Flounder’s little face that he is not enjoying this as he struggles to break free.

Figure 2: The Carmen Miranda-esque fish twerking her buttocks against Flounder.

The Little Mermaid, 1989. Screenshot.

Therefore, “Under the Sea” not only furthers the musicals’ trope of characters of colour as mere entertainers but represents this non-white culture as sexually uninhibited and disrespectful of consent. However, given the elaborate Berkeley-esque choreography, in which these ethnic coded fish are metamorphosed into abstract patterns, the spectator may not be aware of quite how sexually suggestive and racist this dance sequence is.

The orgiastic frenzy of “Under the Sea” is in stark contrast with the type of dancing performed on land by white people. While undersea life is coded as multiethnic and promiscuous, society on land is exclusively white and represented as human characters rather than fish that have been anthropomorphised into the racial stereotypes. Most importantly, human land life is sexually chaste. While the fish gyrate in orgiastic promiscuity, the only dancing that occurs on land is the brief sequence in which Ariel and Eric perform a ballroom waltz. This European dance is not only indicative of the type of dance associated with white performers in film musicals, such as Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, but in contrast to the sexualised calypso-grindings of the fish, is a dance in which sexuality is sublimated into the choreography. As Elizabeth Sells points out, the waltz has been a popular metaphor for sexuality because of how it both represents but also replaces the sexual act (113). The choreography of the waltz (with legs entwined while upper torsos remain distanced) is way of containing eroticism into “(an)aesthetic sexuality” (Sells 113). Indeed, life on white land is so sexually reserved that inspiring a soft kiss is represented as one of the major obstacles that Ariel must overcome. Therefore, it needs the highly sexed fish, performing the erotically suggestive “Kiss the Girl”, to incite Prince Eric even to consider making such a sexual advance as kissing Ariel. During the song, Sebastian croons in Eric’s ear while the other fish engineer sexually suggestive imagery (such as spurting water ejaculations) to agitate Eric’s reserved sexual desires. While this sequence has received criticism for Eric not asking permission for the kiss (something addressed in the 2023 remake), it should be noted that it is, again, the fish who are both encouraging and stimulating Eric’s advances through their sensual music and sexualised choreography.

While The Little Mermaid may code the fish as multiethnic, and conflate their racial identification with sexual promiscuity, it is perhaps most explicitly racist in its representation of the story’s villain, Ursula.

Those “Poor Unfortunate Souls” seduced by the black-market magic of the Welfare Queen

Much of the criticism of The Little Mermaid has been intrigued by the representation of the villain, Ursula (Griffin; Sells; Li-Vollmer and LaPointe; Trites). On the one hand, Ursula can be seen as the embodiment of 1980s fatphobia—this was the decade when gyms and fitness became big business (Dworkin and Wachs)—and homophobia. In comparison to Ariel’s Barbie-doll dimensions, Ursula is an “overweight, ugly woman” (Trites 150) and, given her masculine voice and the way her tentacles embrace and caress Ariel, can also be read as queer coded (Helmsling; Li-Vollmer and LaPointe; Roth). Yet although Ursula is represented as fat, queer and the villain of the narrative, her iconography is also an homage to many of the camp icons of cinema—notably the drag queen Divine (Griffin 146) and Norma Desmond of Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950) (Bell 116). Ursula’s performance in “Poor Unfortunate Souls” is also one of the few critiques of heteronormativity to feature in Disney. As Laura Sells argues, drag queen coded Ursula, through her caricaturing of traditional gender roles, demonstrates that all gender is a masquerade (182). This is most obvious when Ursula displays how her magic has “helped” poor, unfortunate Merfolk by conjuring a vision of two Merpeople who are lonely and unloved because of their body shapes. The Merman is skinny while the Merwoman is fat. Ursula then transforms their bodies into male muscularity and female svelteness, and this automatically solves their problems as they are now “able” to fall in love. On one level, this can be read as supporting the body fascism of Disney’s representations (Herbozo et al.) but it can also be interpreted as Ursula’s critique of heteronormativity and traditional gendered iconography. Given that Ursula can shapeshift (she later assumes the appearance of the Ariel-looking Vanessa), yet chooses to remain resplendently corpulent, the scene can be read as mocking 1980s diet and exercise culture and naïve expectations of heterosexual romance.

Although critics have noted the ambivalence of Ursula (she is either reinforcing queerphobia and fatphobia or is a gender iconoclast deconstructing heteronormativity) there has been considerably less attention paid to how she is coded in terms of racial identification. Although the fish may be coded as a multiethnic community, all the Merpeople—such as King Triton and his daughters—are white. By contrast, Ursula is the only Merperson depicted with a dark epidermal hue. Most importantly, when Ursula first appears in the film she is lounging in her cave, gazing into her magic mirror (arguably, a metaphor for TV) while eating literal fast food in the form of some very lively grubs. This image references the 1980s media stereotype of the welfare queen who was depicted as a fat, lazy, woman of colour who spent her days watching TV, stuffing her face with fast food while claiming welfare benefits. Although the “original” welfare queen was a benefit fraud (a Chicago-based woman named Linda Taylor who claimed welfare benefits through having several addresses and impersonating a variety of people [Kohler-Hausmann 762]), the discourse of “welfare queen” evolved to become a caricature of “lazy, sexually promiscuous (typically African American) women who shirked both domestic and wage labor” (Kohler-Hausmann 757). Despite the inaccuracy of this media stereotype, the welfare queen became a key scare tactic within the Reagan presidential campaign. Soon, the trope of the welfare queen “would become the embodiment of all that had gone wrong with America” (Pimpare 74) and would feature not only in right-wing political campaigns as a threat to the fiscal and moral economy of the USA but would appear in various pop culture representations. Many 1980s films represented the welfare queen as the villain and even horror cinema of the period can be seen to engage with social anxieties about this character. For example, Amy Taubin argues that it is possible to read the final sequence of Aliens (James Cameron, 1986), in which the dark coloured, alien queen is finally revealed as spending all day lying about her lair and producing babies, as a metaphor for the welfare queen (9).

These anxieties about the welfare queen can be seen to condense in the representation of Ursula. Not only does Ursula correspond to the character traits of the welfare queen (she is dark skinned, fat, indolent, lazy and sexually insatiable) but, in her cottage industry of selling black magic, she is subverting the system of hard work that is the bedrock of USA capitalist society. Lazy Merpeople don’t even have to engage in the neoliberalist labour of diet and exercise when they can acquire body-transformation spells from Ursula. As Silvia Federici has researched, magic has always been deemed a threat to capitalism because it challenges the “rationalization of work” by allowing people to obtain what they want without engaging in the necessary labour (172). It could even be argued that Ursula’s cottage industry of body transforming spells is a metaphor for drug dealing—especially physique changing drugs such as steroids or amphetamine fat burners. The sequence then progresses into one of the most visually horrific images of the film when Ursula invades Ariel’s body—orally penetrating her with a magic tentacle to steal her voice. As in the Alien franchise, where the monsters penetrate their human victims via their mouths, this is an image often read as a metaphor of rape (Greven 129).

Figure 3: Ursula’s magic tentacle orally penetrating Ariel. The Little Mermaid, 1989. Screenshot.

However, the scene ends “happily” given that Ariel—in the classic motif of rebirth via emerging from sea water—has now escaped the horror of this debauched aquatic society. The conservative spectator can breathe a sigh of relief that Ariel has managed to flee this unruly culture that is filled with promiscuous, ethnic fish and magic-dealing welfare queens—a world which, as summarised by Sebastian in the final line of “Under the Sea”, is literally “down in the muck.” Now, Ariel has ascended to the superior, clean land of sexual chasteness and propriety which, most importantly, is exclusively white.

The Little Mermaid (2023)

The 2023 live action remake received mixed reviews from journalists with complaints that the film was too long, featured dubious CGI and that the new songs—“The Scuttlebutt” in particular—lacked the usual Menken magic (Kermode; Morris). However, all reviews were united in their praise of Halle Bailey’s performance of Ariel, especially her exquisite singing. Robyn Muir commended the remake for giving the heroine more agency by representing Ariel, rather than Eric, as steering the ship which impales Ursula (5). The “Kiss the Girl” sequence also contained a subtle change in the lyrics to denote that the kiss was now consensual rather than Eric taking liberties.

If Ariel was a more feminist character in the remake, Eric (Jonah Hauer-King) was also given a greater role than merely “a prize bequeathed to the heroine” (Davis, Handsome Heroes 170). The 1989 version was unusual within the genre of film musicals for lacking what Rick Altman labels a “dual focus narrative” (16–28). In musicals, both the male and female leads are given equal scenes—often with comparable “I want” songs—which demonstrate that, although they may appear to represent irreconcilable differences (such as, for example, socio-economic class), they also share similar beliefs and ideologies (Altman 16–28). The Little Mermaid (2023) mobilised this dual focus narrative by giving Eric an “I want” song—“Wild Uncharted Waters”—to demonstrate that, like Ariel, he dreams of exploring other cultures. Although from seemingly irreconcilable societies, Eric and Ariel share similar ambitions. This was further emphasised by the visual motif in which the iconography of Ariel’s cave of wonders is echoed later in the film by Eric’s library/observatory. When Ariel discovers Eric’s observatory, the camera repeats the low angle point of view that Sebastian had when first finding Ariel’s cave and it becomes apparent that both Eric and Ariel are united by their love of exploring and learning about new cultures.

However, the most important difference was how the 2023 version attempted to address the racism inherent in the original. First, the film featured a woman of colour, with unstraightened hair, as Ariel—thus affirming that black looks are beautiful and worthy of Disney princess status. Second, the character of Ursula was also reworked. Played by white Melissa McCarthy, Ursula is no longer represented with a dark epidermal hue. Although McCarthy is famous for her roles as unruly women (Smith 166), this unruliness is always tempered by the way McCarthy herself denotes middle-class whiteness (Meeuf 140). Therefore, any allusions to Ursula as a welfare queen were no longer present in the remake.

Most significant was that the 2023 film no longer featured caricatured racist iconography. Sebastian’s exaggerated lips did not feature on the new photorealistic crab nor were any of the other fish represented as racist stereotypes. Most importantly, the 2023 remake no longer conflated nonwhite identifications with sexual debauchery. “Under the Sea” may still contain the linguistic innuendoes in its lyrics but these were not anchored with images of the overly tactile fish grabbing hold of each other’s body parts to make sweet music together. There was also no Carmen Miranda-esque fish twerking against tween Flounder. The final sequence of “Under the Sea” does still echo Berkeley (perhaps even more than the original) as the high camera angle transforms the dancing fish into an abstract kaleidoscopic pattern.

Figure 4: The Berkeley-esque high-angle cinematography transforming the dancing fish into a kaleidoscopic pattern of abstract shapes. The Little Mermaid, 2023. Dir. Rob Marshall, Walt Disney Studios. Screenshot.

However, none of the fish are clinging to each other’s bodies but instead are shapes dancing alone within line formations. In a very touching development, Ariel is not bored by the song but now joins in and is given a charming descant to demonstrate Bailey’s vocal skills. Ariel’s engagement with the song suggests that she does not dislike aquatic life but simply wishes to explore new cultures.

In another key narrative development, the “Under the Sea” sequence is then echoed by the market dance scene on Eric’s island—replacing the waltz of the 1989 original. In the market scene, Calypso music—a contrafact of “Under the Sea”, reworking many of the harmonic progressions of the song—inspires Eric, Ariel and all the other people at the market to dance to the infectious rhythms.[3] As in “Under the Sea”, the same primary colours are foregrounded so that women’s whirling dresses echo the visual motif of the spinning flat fish. Similarly, the sequence also develops into a kaleidoscope of colours in which the characters appear more like shapes than people. This visual repetition links the human world with the Merworld and reinforces the message delivered by the island’s Queen in her soliloquy at the film’s conclusion: the two cultures of Mer and land are not as different as previously thought. This is further enhanced by the way the animators modelled the photorealistic fish in “Under the Sea” on the movements of dancers from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre (Travis)—thus evoking greater anthropomorphism of the sea creatures and heightening their similarity with the market dancers.

Conclusion: But Part of Whose Colour-Blind, Heteronormative World?

This article has argued that the 2023 remake removed the racist stereotypes and sexualised racism of the 1989 original. Instead of depicting a binary of a multiethnic, sexually debauched and crime-ridden Mer world set against sexually reserved, civilised, white human culture, the remake attempts to demonstrate similarity across both societies by utilising the dual focus narrative to link Ariel and Eric and echoing the “Under the Sea” dance sequence in the marketplace calypso. The 2023 Little Mermaid therefore challenges the implicit white supremacist ideology of the original. Arguably, this is why the casting of Halle Bailey as Ariel “received significant racist backlash” (Muir 2), which culminated in the #notmyariel hashtag. It can be speculated that Twitter trolls were not merely upset by how the casting of a Black Ariel would continue “Disney’s new vision” of expanding its representation of race and ethnicity (Shearon Roberts 5) but that it would challenge the white supremacist narrative of the 1989 animated musical.

However, in its attempt to revise the problems of racial representation from the 1989 film, the 2023 remake can be critiqued for reducing race to a signifier that has no socio-political or historical significance. Marcus Ryder points out that the 2023 narrative may feature casting that is “beautifully ‘colour blind’”, but it therefore demonstrates no awareness of the history of the Caribbean island setting—especially its colonial exploitation and function in slave trading industries (Adderley). Representing a Caribbean island in the nineteenth century as a utopia in which all races mix happily is not only historically inaccurate but can also be accused of obfuscating legitimate issues. Arguably, this is a problem which features in all period dramas which utilise diverse or “colour-blind” casting. As Christine Geraghty explains, the spectator is placed in a confusing position given that they are expected not to see skin colour as significant yet recognise the casting as representing multicultural diversity (171). Perhaps even more problematic is that this trope can reduce race merely to a visual aesthetic. This is especially evident in the dance sequences set on the island. As has been discussed earlier, the marketplace dance echoes “Under the Sea” not only through its contrafact of the tune but in its Berkeley aesthetic of representing the dancers as abstract, swirling shapes. The sequence’s final montage of dancers in colourful costumes becomes merely a kaleidoscope of patterns and thus reduces racial diversity to mere visual spectacle. Devoid of historical and social significance, race in this marketplace dance functions only as an aesthetic of colour.

This reduction of race to a mere aesthetic can also be dangerous in obfuscating the significance of other sequences which would usually be read as racially charged. For example, the opening shots of the market sequence is an extended long take offering only Ariel’s point of view as she wanders around the market, gazing at the marketeers offering their wares. In comparison to the usual shot-reverse-shot editing found throughout the rest of the film, this sequence is a sustained long take of a low angle, point of view. This type of cinematography usually denotes a character’s disorientation (often amazement or fear) when they are in a new, strange environment. Given that Ariel has never seen a market before, this cinematography can be read as merely suggesting her amazement. Yet an alternative reading is also possible in which this sustained long take can be seen to replicate a tourist gaze marvelling at the exoticism of the nonwhite Caribbean market. However, given that the film has coded race as a mere aesthetic of colour, then the ideology of this sequence is obfuscated. The sequence’s tourist gaze is merely marvelling at the colourful, rather than raced, Caribbean market. It is also significant that this gaze, suggesting uncertainty and fear, resumes the standard editing of reverse field cuts only when the white Jodi Benson (who voiced Ariel in the 1989 version) makes a cameo appearance. The change in cinematography denotes that Ariel now feels less uneasy with the exotic market but this only happens when she encounters the very reassuring (and, for the spectator, nostalgic) image of this lovely, white woman.

Finally, it is worth observing that the 2023 remake is, arguably, less progressive in queer representation than the original. Although Melissa McCarthy has spoken of how her performance of Ursula was inspired by drag queen aesthetics (Robledo), she is clearly not a drag queen but a middle-class, heterosexual, cis woman. Unlike the 1989 Ursula, with her deep voice and touchy-feely tentacles, McCarthy’s sea witch is definitely not lesbian coded. Also, missing from the 2023 “Poor Unfortunate Souls” is the moment when Ursula mocks heteronormativity. The lyrics still reference a love-starved couple but there is no illustration of them. Therefore, Ursula’s queer critique of heteronormative romance and gendered standards of beauty is lost. In this respect, while The Little Mermaid (2023) may revise racist iconography, tropes of sexualised racism, and demonstrate similarity between the human and Mer world, it does still raise the question of exactly what type of world Ariel wishes to be a part of. This is not only a world in which race, like the variety of fish under the sea, is merely an aesthetic of different, vibrant colours but also a world in which there is no queer signification at all.

Note

[1] The “I want” (sometimes called “I wish”) song, is the number in which the protagonist sings of their dreams and ambitions. In musicals, it is usually only the hero(ine) who has an “I want” song, promoting greater empathy for the protagonist. By contrast, the supporting characters and villains only have “I am” songs in which they sing about their current situations but do not express hopes for their future.[2] Miranda’s self-referentiality, and the control she exercised over her performances and screen persona, can problematise these readings (Shari Roberts 16).

[3] A contrafact is a musical work based on a prior musical composition.

References

1. Adderley, Rosanne Marion. “New Negroes from Africa”: Slave Trade Abolition and Free African Settlement in the Nineteenth-Century Caribbean. Indiana UP, 2006.

2. Aliens. Directed by James Cameron, 20th Century Studios, 1986.

3. Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical. Indiana UP, 1987.

4. Awkwafina and Daveed Diggs. “The Scuttlebutt.” The Little Mermaid: 2023 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 2023.

5. Bell, Elizabeth. “Somatexts at the Disney Shop: Constructing the Pentimentos of Women’s Animated Bodies.” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, edited by Laura Sells, Lynda Hass, and Elizabeth Bell. Indiana UP, 1995, pp. 107–24.

6. Bendix, Regina. “Seashell Bra and Happy End Disney’s Transformations of The Little Mermaid.” Fabula, vol. 33, no. 3–4, 1993, pp. 280–29. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1993.34.3-4.280.

7. Benson, Jodi. “Part of Your World.” The Little Mermaid: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack,Walt Disney, 1989.

8. The Black Cauldron. Directed by Ted Berman and Richard Rich, Walt Disney Studios, 1985.

9. Bunch, Ryan. “Soaring into Song: Youth and Yearning in Animated Musicals of the Disney Renaissance.” American Music, vol. 39, no. 2, 2012, pp. 182–95. https://doi.org/10.5406/americanmusic.39.2.0182.10. Byrne, Eleanor, and Martin McQuillan. Deconstructing Disney. Pluto Press, 1999.

11. Carroll, Pat. “Poor Unfortunate Souls.” The Little Mermaid: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack,Walt Disney, 1989.

12. Cinderella. Directed by Wilfred Jackson, Hamilton Luske, and Clyde Geronimi, Walt Disney Studios, 1950.

13. Collins, Jim, Hilary Radner, and Ava Preacher. Film Theory Goes to the Movies. Routledge, 2021.

14. Davis, Amy M. Good Girls and Wicked Witches: Women in Disney’s Feature Animations. John Libbey Publishing, 2011.

15. ——. Handsome Heroes and Vile Villains: Masculinity in Disney’s Feature Films. John Libbey Publishing, 2015.

16. Delamater, J. “Busby Berkeley: An American Surrealist.” Wide Angle, vol. 1, no. 1, 1976, pp. 24–29.

17. Diggs, Daveed. “Under the Sea.” The Little Mermaid: 2023 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 2023.

18. Diggs, Daveed, et al. “Kiss the Girl.” The Little Mermaid: 2023 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 2023.

19. Do Rozario, Rebecca-Anne C. “The Princess and the Magic Kingdom: Beyond Nostalgia, the Function of the Disney Princess.” Women's Studies in Communication, vol. 27, no.1, 2004, pp. 34–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2004.10162465.

20. Dyer, Richard. In The Space of a Song: The Uses of Song in Film. Routledge, 2012.

21. ——. Only Entertainment. Routledge, 2005. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203993941.

22. Dworkin, Shari L., and Faye Linda Wachs. Body Panic: Gender, Health, and the Selling of Fitness. NYU P, 2009.

23. Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation. Autonomedia, 2014.

24. Fischer, Lucy. “The Image of Woman as Image: The Optical Politics of Dames.” Film Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 1, 1976, pp. 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.1976.30.1.04a00040.

25. 42nd Street. Directed by Lloyd Bacon, Warner Brothers Studios, 1933.

26. Frasl, Beatrice. “Bright Young Women, Sick of Swimmin’, Ready to… Consume? The Construction of Postfeminist Femininity in Disney’s The Little Mermaid.” European Journal of Women's Studies,vol. 25, no. 3, 2018, pp. 341–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506818767709.

27. The Gang’s All Here. Directed by Busby Berkeley, Twentieth Century Studios, 1943.

28. Geraghty, Christine. “Casting for the Public Good: BAME Casting in British Film and Television in the 2010s.” Adaptation, vol. 14, 2. no. 2, 2021, pp. 168–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/adaptation/apaa004.

29. Greven, David. “Demeter and Persephone in Space: Transformation, Femininity, and Myth in the Alien Films.” Representations of Femininity in American Genre Cinema: The Woman’s Film, Film Noir, and Modern Horror, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, pp. 117–39. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230118836_5.

30. Griffin, Sean. Tinker Belles and Evil Queens: The Walt Disney Company from the Inside Out. NYU P, 2000.

31. Harrod, Mary and Katarzyna Paszkiewicz. Women Do Genre in Film and Television. Taylor & Francis, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315526096.

32. Hauer-King, Jonah. “Wild Unchartered Waters.” The Little Mermaid: 2023 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 2023.

33. Helmsing, Mark. “‘This Is No Ordinary Apple!’: Learning to Fail Spectacularly from the Queer Pedagogies of Disney’s Diva Villains.” Disney, Culture, and Curriculum, edited by Jennifer A. Sandlin and Julie C. Garlen, Routledge, 2016, pp. 89–102. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315661599-15.

34. Herbozo, Sylvia, et al. “Beauty and Thinness Messages in Children’s Media: A Content Analysis.” Eating Disorders, vol. 12, no. 1, 2004, pp. 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260490267742.

35. Hurley, Nat. “The Little Transgender Mermaid: A Shape-shifting Tale.” Seriality and Texts for Young People: The Compulsion to Repeat, edited by Mavis Reimer et al., Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 258–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137356000_14.

36. Kermode, Mark. “The Little Mermaid Review: Bland but Good-Natured Disney Remake.” The Guardian, 27 May 2023, www.theguardian.com/film/2023/may/27/the-little-mermaid-review-bland-but-good-natured-disney-remake-halle-bailey.

37. Kohler-Hausmann, Julilly. “Welfare Crises, Penal Solutions, and the Origins of the ‘Welfare Queen’.” Journal of Urban History, vol. 41, no. 5, 2015, pp. 756–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144215589942.

38. Kunze, Peter C. Staging a Comeback: Broadway, Hollywood, and the Disney Renaissance. Rutgers UP, 2023. https://doi.org/10.36019/9781978827844.

39. Lacroix, Celeste. “Images of Animated Others: The Orientalization of Disney’s Cartoon Heroines from The Little Mermaid to The Hunchback of Notre Dame.” Popular Communication: The International Journal of Media and Culture, vol. 2, no. 4, 2004, pp. 213–29. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15405710pc0204_2.

40. Li-Vollmer, Meredith, and Mark E. LaPointe. “Gender Transgression and Villainy in Animated Film.” Popular Communication, vol. 1, no. 2, 2003, pp. 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15405710PC0102_2.

41. The Little Mermaid. Directed by John Musker and Ron Clements, Walt Disney Studios, 1989.

42. The Little Mermaid. Directed by Rob Marshall, Walt Disney Studios, 2023.

43. McCarthy, Melissa. “Poor Unfortunate Souls.” The Little Mermaid: 2023 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 2023.

44. Meeuf, Russell. “Class, Corpulence, and Neoliberal Citizenship: Melissa McCarthy on Saturday Night Live.” Celebrity Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2016, pp. 137–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1044758.

45. Mellencamp, Patricia. A Fine Romance: Five Ages of Film Feminism. Temple UP., 1995.

46. Morris, Wesley. “The Little Mermaid Review: Disney’s Renovations are Only Skin Deep.” New York Times, 24 May 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/05/24/movies/little-mermaid-review-halle-bailey.html.

47. Muir, Robyn. “Disney’s The Little Mermaid Review: Ariel Finally Finds her Feminist Voice”, The Conversation, 30 May 2023, theconversation.com/disneys-the-little-mermaid-review-ariel-finally-finds-her-feminist-voice-206695.

48. Murphy, Patrick D. “The Whole World was Scrubbed Clean: The Androcentric Animation of Denatured Disney.” From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, edited by Laura Sells, et al., Indiana UP, 1995, pp. 125–36.

49. O’Brien, Pamela Colby. “The Happiest Films on Earth: A Textual and Contextual Analysis of Walt Disney’s Cinderella and The Little Mermaid.” Women’s Studies in Communication, vol. 19, no. 2, 1996, pp. 155–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.1996.11089811.

50. Pimpare, Stephen. Ghettos, Tramps, and Welfare Queens: Down and Out on the Silver Screen. Oxford UP, 2017.

51. Powell, Dick. “I’m Young and Healthy.” Soundtrack: 42nd Street, Warner Bros., 1933.

52. Rabinowitz, P. “Commodity Fetishism: Women in Gold Diggers of 1933.” Film Reader, vol. 5, 1982, pp. 141–49.

53. Reimer, Mavis, et al. Seriality and Texts for Young People: The Compulsion to Repeat. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137356000.

54. Roberts, Shari. “The Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat”: Carmen Miranda, a Spectacle of Ethnicity.” Cinema Journal, vol. 32, no.3, 1993, pp. 3–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1225876.

55. Roberts, Shearon. Recasting the Disney Princess in an Era of New Media and Social Movements. Lexington Books, 2020.

56. Robbins, Allison. “Busby Berkeley, Broken Rhythms and Dance Direction on the Stage and Screen.” Studies in Musical Theatre, vol, 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1386/smt.7.1.75_1.

57. Robledo, Jordan. “The Little Mermaid: Melissa McCarthy says Drag Queens Influenced Her Ursula Role.” Gay Times,9 Apr.2023, www.gaytimes.co.uk/films/the-little-mermaid-melissa-mccarthy-says-drag-queens-influenced-her-ursula-role.

58. Roth, Matt. “The Lion King: A Short History of Disney-Fascism.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, vol. 40, 1996, pp. 15–20, www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC40folder/LionKing.html.

59. Rubin, Martin. Showstoppers: Busby Berkeley and the Tradition of Spectacle. Columbia UP, 1993.

60. Ryder, Marcus. “Disney’s The Little Mermaid, Caribbean Slavery and telling the Truth to Children.” Black on White TV, 2023, blackonwhitetv.blogspot.com.

61. Sandlin, Jennifer A., and Julie C. Garlen. Disney, Culture, and Curriculum.Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315661599.

62. Sebring, Jennifer Hammond, and Pauline Greenhill. “The Body Binary: Compulsory Able-bodiedness and Desirably Disabled Futures in Disney’s The Little Mermaid and The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea.” Marvels & Tales, vol. 34, no. 2, 2020, pp. 256–76. https://doi.org/10.13110/marvelstales.34.2.0256.

63. Sells, Laura. “Where Do the Mermaids Stand?” Voice and Body in The Little Mermaid.” In From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture, edited by Laura Sells, et al., Indiana UP. 1995, pp. 175–92.

64. Sells, Laura, et al. From Mouse to Mermaid: The Politics of Film, Gender, and Culture. Indiana UP, 1995.

65. Sleeping Beauty. Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, Clyde Geronimi, Eric Larson, and Les Clark, Walt Disney Studios, 1959.

66. Smith, Frances. “Melissa McCarthy: Gender, Class and Body Politics in Contemporary US Comedy.” Women Do Genre in Film and Television, edited by Mary Harrod and Katarzyna Paszkiewicz, Taylor & Francis, 2017, pp. 164–78. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315526096-12.

67. Spencer, Leland G. “Performing Transgender Identity in The Little Mermaid: From Andersen to Disney.” Communication Studies, vol. 65, no. 1, 2014, pp. 112–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.832691.

68. Stover, Cassandra. “Damsels and Heroines: The Conundrum of the Post-feminist Disney Princess.” LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013, p. 29. https://doi.org/10.5642/lux.201301.29.69. Sunset Boulevard. Directed by Billy Wilder, Paramount Pictures, 1950.

70. Taubin, Amy. “Invading Bodies.” Sight and Sound, vol. 2, no. 3, 1992, pp. 8–10.

71. Travis, Ben. “Rob Marshall on Making The Little Mermaid into an All-Out Underwater Musical.” Empire, 4 Nov. 2023, www.empireonline.com/movies/news/rob-marshall-the-little-mermaid-underwater-musical-exclusive.

72. Trites, Roberta. “Disney’s sub/version of Andersen’s The Little Mermaid.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 18, no. 4, 1991, pp. 145–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.1991.10662028.

73. Tseёlon, Efrat. “The Little Mermaid: An Icon of Woman’s Condition in Patriarchy, and the Human Condition of Castration.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, vol 76, 1995, pp. 1017–30.

74. White, Susan. “Split Skins: Female Agency and Bodily Mutilation in The Little Mermaid.” Film Theory Goes to the Movies, edited by Jim Collins, Hilary Radner, and Ava Preacher, Routledge, 2021, pp. 182–95.

75. Whitley, David. The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation: From Snow White to WALL-E. Ashgate, 2021.

76. Wright, Samuel, E. “Kiss the Girl.” The Little Mermaid: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack,Walt Disney, 1989.

77. ——. “Under the Sea.” The Little Mermaid: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack,Walt Disney, 1989.

78. Zarranz, Libe Garcia. “Diswomen Strike Back? The Evolution of Disney’s Femmes in the 1990s.” Atenea, vol.27, no. 2, 2007, pp. 55–65.

Suggested Citation

Richardson, Niall. “Part of Whose World? How The Little Mermaid (2023) Attempts to Revise the Racist Tropes of the 1989 Animated Film Musical.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 27, 2024, pp. 94–109. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.27.08

Niall Richardson teaches film and media studies at the University of Sussex where he convenes MA Gender and Media. He is the author of the monographs The Queer Cinema of Derek Jarman (2009), Transgressive Bodies (2010), Ageing Femininity on Screen (2018) and Trans Representations in Contemporary Popular Cinema (2022).