Music in “Reticent” Cinema

James Wierzbicki

[PDF]

Abstract

Expanding on ideas presented by Danijela Kulezic-Wilson in a chapter of her 2020 book Sound Design Is the New Score, this article explores the nature of “reticent” films both old and new, and it suggests that often it is because their soundtracks have so little to “say” that these films communicate so very, very much.

Article

In the chapter of her 2020 Sound Design Is the New Score that is devoted largely to the works of Peter Strickland, Danijela Kulezic-Wilson focused on “the aesthetics of reticence”, advocates of which, she wrote, “insist that restraint and a certain level of ambiguity are the basic conditions for allowing individuated responses to film and encouraging more active involvement with the text” (61–2). She noted that the idea of “reticent” filmmaking was hardly new with Strickland, and she made the point that held-back filmic storytelling, whenever it appeared, has always stood in sharp contrast to the cinematic norm. That norm has long been known as film’s “classical” style, a style of filmmaking characterised by the apparent fact that virtually all its elements—not just the dialogue and action but also the lighting and the costumes, and certainly also the sound effects and musical underscores—serve, as Susan Hayward succinctly put it in a dictionary of concepts common to film studies, “to explain, and not obscure, the narrative” (64).

The explanatory functions of extradiegetic music within the classical-style film have been carefully delineated by Claudia Gorbman, Kathryn Kalinak, and others who in the 1980s emerged from postgraduate programmes in English and comparative literature to become the first generation of modern-day film-music scholars, and they can be reduced to Kalinak’s statement that “first and foremost, music serves the story” (xv). But how does music function within the non-classical film, or, as some writers would have it—doubtless mindful that the term is “loaded with hidden assumptions and all sorts of connotations that are potential points of contention” (Thanouli 195)—the “post-classical” film? Do the soundtracks of these films obscure their narratives? If the soundtrack of the classical-style film has a lubricative effect on the story it serves, does the soundtrack of the non-classical, or post-classical, film have an abrasive effect? Are the soundtracks of such films irrelevant, existing in tandem with the narratives but having no real bearing on them? Or do they somehow complement the narratives—providing a contrapuntal commentary, perhaps, or a metonym-filled gloss—in a way that goes far beyond the conventions of what David Bordwell, with all due respect, called “the ordinary film” (Bordwell et al., Classical Hollywood Cinema 10)?

Expanding on some of Kulezic-Wilson’s ideas, this contribution to Alphaville explores the nature of reticent film both old and new, and it suggests that often it is because their soundtracks have so little to “say” that these films communicate so very, very much.

Signals

For most of its existence, cinema has been a storytelling medium. For most of cinema’s existence, too, scenarists have structured their work so that ultimately—in dark dramas and complex romances as much as in picaresque adventures and madcap comedies—the stories “make sense”, to the extent that entire plots can be summarised in just a sentence or two. And in most of the thousands upon thousands of storytelling films that have been produced and exhibited since early in the twentieth century, the “sense-making” of the films’ narratives has been assisted by music.

The films that prompt this essay tell stories. They are not examples of what Tom Gunning in 1986, specifically referring to the earliest manifestations of “moving pictures” yet anticipating the animate “selfies” that nowadays circulate on YouTube and Facebook, called the “cinema of attractions” (64). They are not instances of photojournalism, or documentaries that purport to show what supposedly happened at a particular place and time; nor are they abstract plays of light and image, with or without sound, that fit into the broad category of avant-garde cinema. These films are all works of fiction, some of them adapted from literary sources and some of them authored, not just with screenplays written but with stories wholly invented, by the persons who served as their directors. They are all more or less scripted, and their on-screen action features not “real people” but actors pretending to be real people. Their narratives, however, are anything but straightforward, and their music—whether it be music that the films’ characters supposedly can hear or music that reaches only the ears of the audience—rarely offers a hint as to what the characters might be thinking, or feeling or even doing.

Music in the classical-style film abounds with hints that relate to what the main characters think, feel, and do. Such hints are in most cases redundant. Assuming that one has been following the dialogue and attending to the actors’ body language, does one really need to hear a romantic-sounding underscore to know that the male and female leads are “having a moment”? Does one really need to be “told”, by means of fast-paced and dissonance-filled music, that a protagonist is engaged in a chase or a punch-up? In a comic scene that shows an oaf getting a much-deserved pie in the face, does one really need to have the splashy impact marked by a musical “hit” in order to be urged to laugh? The answers to these questions should, of course, be in the negative. Watching classical-style films, one does not need to hear music in order to “get the message”. Yet there can be no denying, as any cinephile will attest, that such music is much appreciated by its listeners, and that it has a potent effect on how smoothly the audience member “gets” the filmic message.

****

David Bordwell titled the opening chapter of his (and Janet Staiger’s and Kristin Thompson’s) 1985 book on the classical-style film “An Excessively Obvious Cinema”. Often quoted, the phrase is unfortunately misleading, because the adverb implies that the many devices that aid in the classical-style film’s storytelling collectively go “over the top”. But Bordwell meant nothing of the sort when he wrote this seminal text that celebrates what he called not just “the ordinary film” but also “the typical Hollywood film” and “the quietly conformist film that tries simply to follow […] the rules” (3, 10). He was not suggesting that the many narrative clues—musical or otherwise—embedded in the classical-style film are more than what they need to be; on the contrary, he was saying that even in run-of-the-mill classical-style films, where the balance of elements is usually just as much “right” as in the films that regularly top the lists of all-time favourites, these clues are so deftly woven into the whole that they tend to go unnoticed. Bordwell ended his chapter with a reference to a passage in Edgar Allan Poe’s 1844 “The Purloined Letter” in which the amateur detective C. Auguste Dupin explains to the story’s narrator why the just-solved mystery posed such difficulties to the police. “There is a game of puzzles,” Dupin tells his friend, “which is played upon a map”, a game in which one player

requires another to find a given word—the name of town, river, state, or empire—any word, in short, upon the motley and perplexed surface of the chart. A novice in the game generally seeks to embarrass his opponents by giving them the most minutely lettered names; but the adept selects such words as stretch, in large characters, from one end of the chart to the other. These, like the over-largely lettered signs and placards of the street, escape observation by dint of being excessively obvious (215).

With his paraphrase of Poe’s words, Bordwell generated a memorable chapter title; at the same time, he blunted his point.

There is nothing excessively obvious about the verbal, visual, and sonic signals in the classical-style film. The signals are there, in abundance, but only rarely do they call attention to themselves, and it is the crafty mix of their subtlety and their plentitude that in large part makes storytelling in this genre, as much in today’s international blockbusters as in the vintage Hollywood films that were the prime subject of Bordwell’s study, so enjoyably “comprehensible and unambiguous” (3). The “reticent” cinema that intrigued Kulezic-Wilson is not necessarily incomprehensible. But often such cinema is very much ambiguous.

Ambiguity

In a footnote attached to the first page of the 1946 second edition of his treatise on ambiguity, William Empson explains that after receiving feedback on the book’s original publication sixteen years earlier he adjusted his definition of the key term “to avoid confusing the reader”. To confuse the reader/listener is perhaps the goal of hucksters, con artists, and others who for a living spout perfectly parseable mumbo-jumbo. It was certainly not the goal of a writer like Empson, who as a twenty-four-year-old Cambridge scholar took an almost scientistic approach to a distillation of what some would say is the very lifeblood of worthy literature. The phrase for which Empson found it necessary to apologise described ambiguity as a quality that “adds some nuance to the direct statement of prose”; the revised phrase had it that ambiguity is “any verbal nuance, however slight, which gives room for alternative reactions to the same piece of language” (1).

Those who seek to understand the workings of “reticent” cinema would do well to review Empson’s logical breakdown of ambiguities. The first of his seven types of ambiguity arises “when a detail is effective in several ways at once”; his “second-type” ambiguity has to do with “two or more alternative meanings [that] are fully resolved into one”; “the condition for third-type ambiguity is that two apparently unconnected meanings are given simultaneously”; in a fourth type of ambiguity, Empson writes, “alternative meanings combine to make clear” an author’s “complicated state of mind”; a fifth type of ambiguity results from “a fortunate confusion” of ideas, or expressions of emotion, on the part of the author; a sixth type entails details that at first seem “contradictory or irrelevant” but which are presented in such a way that “the reader is forced to invent interpretations”; finally in Empson’s list, a “seventh type” of ambiguity contains a “full contradiction [that marks] a division in the author’s mind” (v–vi).

Empson’s sixth type of ambiguity is, I think, especially relevant to considerations of both the music and the narrative content of “reticent” cinema. This type of ambiguity, Empson writes, “occurs when a statement says nothing” (176; emphasis added); assuming that such a statement is made up of words that in themselves are meaningful, the reader has little choice but “to invent statements of his own” that somehow “explain” the words’ odd combination, and probably these reader-invented statements, even as they exist only within the mind of a single reader, will “conflict with another” (176). Unlike such ultimately resolved instances of verbal ambiguity as puns and irony, the statement that “says nothing” remains forever open to interpretation. And by ‘saying’ what appears to be nothing, it potentially speaks volumes.

To illustrate his chapter, Empson draws upon such exemplars of “the cult of vagueness” as quips by “the dowagers of Oscar Wilde’s plays” and passages from “nonsense writers like [Edward] Lear and Lewis Carroll” (187), but he relies as well on quotations from Shakespeare and the Bible, and from poets as wide-ranging as Alexander Pope, George Herbert, Omar Khayyam, and W. B. Yeats. Focussing for several pages on Yeats, Empson notes that his sixth type of ambiguity does not arise from the “wavering and suggestive indefiniteness” that in so much nineteenth-century English poetry is “often merely weak”; rather, it springs from constructions like the contradictory advice about brooding found in a Yeats poem that Empson thinks is so well-known that its title need not be mentioned (it is “Fergus and the Druid”, from Yeats’s 1893 collection The Rose), a construction that “has a great deal of energy and sticks in your head, […] because the opposites left open are tied around a single strong idea” (190). That the idea is “strong” is immediately evident to the sensitive reader, Empson observes, yet the essence of the idea remains elusive, and thus for so long as it is remembered its ambiguity provides food for thought.

****

Is it not the same with certain films? For those seeking entertainment of the sort traditionally promised and delivered by the “ordinary” movie, time spent with the modestly budgeted Strickland films that Kulezic-Wilson mentions (Katalin Varga (2009), Berberian Sound Studio (2012), The Duke of Burgundy (2014)), or with such mid-century masterpieces as Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957), Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (L'Année dernière à Marienbad, 1961), and Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 (1963), or with such star-studded productions as Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), and Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups (2015), is surely frustrating. These films feature plenty of music, but this music—whether composed for the film or borrowed from pre-existing sources—rarely serves, as Gorbman writes is typical of the classical-style film score, to “ward off the displeasure of uncertain signification” (58). Indeed, this music—because it does not imitate or illustrate on-screen action, or attempt to “explain” the characters’ unspoken thoughts—contributes much to the films’ enduring fascination. Amongst filmgoers of a certain persuasion this hardly causes displeasure. On the contrary: Whereas the huge “general” audience for movies around the world repeatedly demonstrates, with its behaviour at the box-office, “a massive distaste for [cinematic] ambiguity and multivalence”, a small and arguably “elite” audience finds such qualities quite delectable (Brown 10).

By generating what Empson described as a “massive fog”, the best examples of “complete ambiguity” (182) leave their consumers in a state of perpetual doubt, a state whose onset might well push them into debate with fellow-consumers as to the “real meaning” of this or that but which eventually, after such debates come to nothing, settles into a lingering condition of wonderment. The mini-synopsis attached to the IMDb (International Movie Database) on-line page for Bergman’s The Seventh Seal informs us that the film portrays someone who “seeks answers about life, death, and the existence of God”; the IMDb synopses tell us that Lynch’s Mulholland Drive is “about” a “search for clues and answers […] in a twisting venture beyond dreams and reality”, and that Malick’s Knight of Cups is “about” a screenwriter who “undertakes a search for love and self.” Seeking and searching, but never finding, is a theme found often in non-classical cinema. Another common theme has to do with the blurring of fact and fantasy; another has to do with persistent memories that, like the clocks in Salvador Dalí’s famous painting of 1931, seem to “melt” into everyday experience.

According to the IMDb entry, the film that most occupies Kulezic-Wilson’s attention in her Strickland chapter—Berberian Sound Studio, whose central character is a meek British recordist for nature documentaries inexplicably recruited to supervise ghastly sound effects for an Italian horror film—is “a terrifying case of life imitating art.” Boiled down to its essence, the meagre plot of Berberian Sound Studio perhaps merits that bromidic description. But one could argue that what is embodied by the film as a whole—with its deep psychological reverberations, with its pervasive ambience of dislocation, with its unsettling lack of a tidy wrap-up—is actually, like many another example of reticent cinema, a case of art imitating life.

Endings

One of the landmark works in postwar literary criticism begins with a chapter titled “The End”. Published when the Cuban Missile Crisis was fresh in the minds not of not just seasoned academics but of a whole generation of adolescents and young adults, including the female undergraduates at Bryn Mawr College to whom its contents, in the form of a series of lectures, was first addressed, Frank Kermode’s 1966 The Sense of an Ending starts with a digest of several millennia’s worth of “apocalyptic thought” (5). But most of Kermode’s book concerns contemporary fiction, especially fiction of the “anti-novel” type practiced by such French writers as Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Alain Robbe-Grillet. These writers flout convention, Kermode writes, all the while knowing that the “old paradigms continue in some way to affect the way we make sense of the world” (28).

The old paradigm most dominant in novelistic/cinematic storytelling seems to have been first articulated ca. 335 B.C. by Aristotle in his Poetics. Touting his 2022 translation of the Poetics, Philip Freeman noted in an article for the on-line journal Aeon that anyone aspiring “to write a screenplay for a blockbuster film” would do well to look to Aristotle, because Aristotle’s Poetics—even with its “missing and rearranged sections, logical gaps, and the loss of its whole second half on comedy”—remains the best advice there is as to “what makes a story work well.” That advice comprises seven precepts, the most-often paraphrased of which has it, as Freeman summarises in the introduction to his book, that “stories must have a beginning, middle, and end” (xiii).

That a story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and that the events that make up even a long and complex middle section should be discernibly connected with one another, was not an idea that Aristotle invented. Other cultures might see things differently, but it almost goes without saying that most persons steeped in Western thinking—today as much as in Aristotle’s time—feel truly comfortable only with phenomena, narrative or otherwise, that they can for the most part understand. Knowing this, and whether or not they had ever even heard of Aristotle, manufacturers of motion pictures have profitably delivered “understandable” stories to customers ever since the dawn of the classical-style film in the years surrounding the First World War. But the very fact that Aristotle’s dictum seemed to be “a rule” made it for some story tellers—especially in the unsettled wake of the Second World War, as rule-breaking became increasingly fashionable—a provocation.

Jean-Luc Godard’s much-quoted refutation of the Aristotelean “rule” was already a cliché by the time he spoke it in 1966. Reporting on the Cannes Film Festival for London’s Observer in the same year that Kermode’s book was published, Kenneth Tynan wrote that the festival’s events included “a public debate between writers and directors” on the topic of plot, in the course of which the veteran filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot asked Godard: “But surely you agree, M. Godard, that films should have a beginning, a middle part and an end?” To which Godard replied: “Yes, but not necessarily in that order.” According to a website called Quote Investigator, whose contributors specialise in tracking down citational trivia, a book reviewer for the Los Angeles Times in 1964 remarked that in a recently published novel (Charles Haldeman’s The Sun’s Attendant) “those who insist on Aristotle’s story formula—a beginning, a middle, and an end—will get those three goodies but not necessarily in that order.” Quote Investigator also informs us that as early as 1955 the British critic Peter Dickinson wrote, in a review for Punch of Orson Welles’s Confidential Report (a.k.a. Mr. Arkadin), that the plot of this film most certainly “has a beginning, a middle, and an end, although they don’t come in that order.”

****

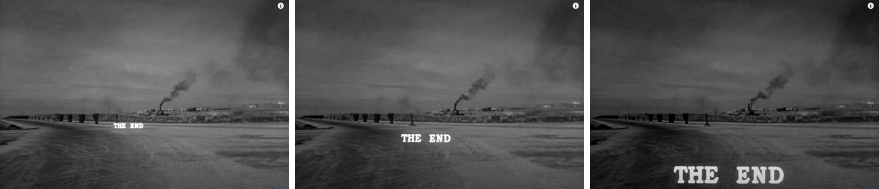

In fact, Welles’s Confidential Report and the dozen or so full-length films that Godard had made up to 1966 do have beginnings, middle sections, and endings that occur precisely in that order. What the narratives of these films notably lack, however, is a sense of closure. Almost as if to tease the audience, the last scene of Confidential Report shows the daughter of the mysterious Mr. Arkadin driving off with a clueless companion as the words “The End” sweep in as if from a distance; this is the end of the film, to be sure, but persons who have tried to understand Arkadin’s character know that this cannot possibly be the end of the story. Most of Godard’s films up through the late 1960s likewise feature on-screen displays of the word “Fin”, and in the films nearest to the date of the anti-Aristotelean quip—Alphaville (1965), Masculin Féminin (1966), Week End (1967)—the typography is graphically “played with” to the extent that even an inattentive audience member knows that the word cannot possibly mean what it says.

Figures 1–3: At the end of Confidential Report, the words “The End” sweep in as if from a distance. This is the end of the film, but certainly not the end of the story. Confidential Report (a. k. a. Mr. Arkadin), dir. Orson Welles. Filmorsa and Mercury Productions, 1955. Screenshots.

Because they reach stopping points but do not really conclude, works of this sort seriously violate the structure of classical-style cinema. Feature films in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s typically begin with title sequences whose music alone gives the audience a summary of all that is to come, and typically the final image of these films is a screen-filling display of the words “The End” underscored by a decisive musical cadence. Classical-style films today tend to exchange the synoptic title sequence for a prologue that is relatively devoid of plot-predicting music, but the directors of these films are just as much aware as were their forebears that people who go to the movies have hearty appetites for entertainment in particular genres, and so before too many minutes pass most of these slow-starting films fairly erupt with a signal that both visually and sonically assures patrons that they have entered the right room of the cineplex; rarely at the end of a modern classical-style film does one see the words “The End”, yet these films’ long dribbles of music-accompanied credits are often preceded by one or another of such now codified “closural signals” as the fade-out or the zoom-out, or a mute action that depicts “leave-taking” or of “something being closed up” (Hock 71–73), and often the pre-credits scenes somehow combine a “resolution [that] sorts out the problems the film has set up” with an “epilogue [that] shows the stability thus achieved” (Walker 7). Amongst all the framing devices standard to the classical-style film, the endings are especially important, and they remind us of the simple fact that most examples of cinema are first and foremost commercial commodities. Obeying “rules” that have less to do with Aristotle than with the marketplace, classical-style films new as well as old start by building up expectations and finish with strong efforts to remind ticket-buyers that they got what they paid for.

What does the audience member “get” from the film that eschews closure? The pay-off is certainly not an immediate sense of satisfaction that within the story all questions have at last been answered, or, on a more deeply psychological level, a fulfilment of “individual and social desire for moral authority, a purposeful interpretation of life, and genuine stability” (Neupert 35). On the contrary, the reward for concentrated time spent with such a film is usually just another confirmation of what hard-bitten persons knew all along to be true. As David Robey writes in his introduction to the collection of essays by Italian novelist and semiotician Umberto Eco gathered under the apt title The Open Work, the story that evades a neat ending “represents by analogy the feeling of senselessness, disorder, ‘discontinuity’ that the modern world generates in all of us” (xiv). Most adults who have been “around the block” a few times acknowledge this feeling but are uncomfortable with it, and so we prefer classical-style films whose well-wrought plots allow us temporary escapes from what Stanley Cavell, reflecting on the Heideggerian implications of Terrence Malick’s 1978 Days of Heaven, called the actual “scene of human existence” (xiv). But some of us, at least once in a while, and perhaps for reasons that justify our own soul-searching, relish the film whose absence of formal closure reminds us—as does Days of Heaven—that this is how life, for better or worse, really is.

Comparing real life not just to conventional fiction but also to conventional Western music, in which dissonances both short-range and long-range tend ultimately to resolve, Royal S. Brown suggests that the subject matter of the cinematic “open work” is more often than not simply an evocation of raw affect. And “affect in its pure state,” he writes,

is neither linear nor does it have a beginning, middle, and an end. There may be points [in life] at which one starts and stops having a particular feeling, but that feeling itself is synchronic and does not invite a structural sense of closure. The necessity for such a sense of closure derives from a need, inherent in the psychology of the occident, for emotional release and/or consummation. (93)

Approaching the same target from a different angle, and quoting from Lloyd Alexander’s translation of Sartre’s Nausea, Kermode in his penultimate chapter writes that “in [real] life there are no beginnings, [none of] those ‘fanfares of trumpets’ which imply structures ‘whose outlines are lost in the mist’” (148). He might have observed as well that in real life there are no endings, no matter how hard we try to package our reminiscences. In an epilogue attached to a turn-of-the-century edition of The Sense of an Ending, Kermode adds that in our ever-flowing courses of existence we are always “stranded in the middle,” and thus “to make sense of our lives […] we need fictions of beginnings and fictions of ends, fictions which unite beginning and end and endow the interval between them with meaning” (190; emphasis added).

Meaning

In the verbose classical-style film, music regularly conveys director-intended “meanings”— about historical periods and geographic locales, about actions and emotions, about unspoken thoughts—that the vast majority of viewers, even if they watched the film in silence, could probably figure out on their own. Music in the reticent non-classical film sometimes does that as well, although mostly in early scenes, as characters are depicted as more or less anchored in quotidian normality before being, as it were, cast adrift. But often music in the non-classical film, especially when it is not composed originally for the film and thus sounds at least somewhat familiar, has no meaning other than what the individual audience member chooses to read into it.

Familiar music in non-classical films may seem cryptic if one insists on trying, for the sake of satisfying a personal need for “consummation”, to decode messages that might not exist. For the musically educated filmgoer, the temptation to do so is surely great. Just reading about Malick’s use of the lonely trumpet calls from Charles Ives’s The Unanswered Question in the muted after-battle scene of The Thin Red Line (Terrence Malick, 1998) perhaps leads some persons to surmise, of course, that the quotations “mean” that the answers to questions about life and death are forever blown’ in the wind. Likewise, a simple awareness of Godard’s use of sharp-edged fragments from various of Beethoven’s string quartets in both Une femme mariée (1964) and Prénom: Carmen (1983) is perhaps enough to convince even cinephiles who have never experienced these films that by this ear-catching technique Godard, of course, “means” that the lives of the main characters are dangerously splintered. Likewise, too, the mere knowledge that the organ music that recurs throughout Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (Solyaris, 1972) is not just something or other from long ago but a Bach chorale prelude based on the sixteenth-century hymn “Ich ruf zu dir” (“I call to you”) is perhaps all the evidence some interpreters need in order to conclude, of course, that the entire “meaning” of this Soviet-era sci-fi film is firmly rooted in Christian values.

Quoted music in non-classical films, like the pop songs in the so-called compiled soundtrack, indeed offers its listeners opportunities to make what Anahid Kassabian, in her 2001 account of for the most part not at all reticent recent Hollywood products, describes as “affiliating identifications” that have much to do with individual filmgoers’ tastes and histories, and such “identifications” indeed “open […] wide” the “psychic field” for interpretation (3). But in archly reticent cinema, which withholds much more than it reveals, quoted music regardless of its source seldom encourages audience members to “read between the lines” of a screenplay and embellish it with their personal feelings. In most cases, the quoted music is simply there, for reasons that defy explanation; if the excerpts of Ives, Beethoven, and Bach in the just-mentioned films do signify what was described, the reality of that signification is something known for sure only to those persons who, for whatever reasons, believe it to be so.

****

Quotation, or at least allusion, permeates works that fall into the portmanteau category of the “postmodern” film. Such films teem almost to the point of overflowing with references to “artefacts” that lie beyond the immediate scopes of their narratives but which likely are within the grasp of many in their audience. Some of these films, almost in game-like fashion, challenge audience members to participate in possibly meaningful intertextual analysis; others of them, perhaps only because nowadays it is fashionable, simply load their footage with what M. Keith Booker, borrowing a phrase coined by Alissa Quart for the sake of his 2007 monograph on postmodern Hollywood, calls cinematic “hyperlinks” (xix, 12). As when scrolling through a typical page on the Internet, individual filmgoers while experiencing such a film can in effect “click” on as many, or as few, of the hyperlinks as they choose. And the simple fact that the links are abundant yet optional makes films of this type, regardless of the nature of their storytelling, endlessly open to interpretation.

Well-known examples of films whose soundtracks, dialogue, and imagery are rich in extra-filmic citations are Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994), Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (Lola rennt, 1998), and Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! (2001). Another is Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which Matthew Flisfeder argues is the cinematic “marker of the transition from modernity to postmodernity” (89). Whether regarded in the form of its original theatrical release or its arguably more open-ended director’s cut (1992), Blade Runner is deliciously filled with icons that Flisfeder says are not so much “direct representations of the past” as they are—and here he paraphrases a key line from Fredric Jameson’s essay “Postmodernism and the Consumer Society”—“representations of the cultural stereotypes of the past” (99).

Underscored throughout with electronic music by the Greek composer who went by the single name Vangelis, Blade Runner sonically pays only fleeting homage—in the form of the occasional throbbing “club” beat, or the occasional whiff of “smoky” jazz—to what audiences in 1982 possibly imagined the film’s characters, from their fictional perspective of a dystopian 2019 (!), took to be symbolic of a stereotypical past. But other allegedly postmodern films are more overt in their musical borrowings. Probably not many filmgoers will know just from hearing it that the main theme and much of the scene-supporting music in Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995), although the score is credited to Paul Buckham, in fact draws liberally from the third movement of Astor Piazzolla’s tango-flavoured 1980 Suite Punta del Este, but doubtless there is not a cinephile alive who can suppress all manner of thoughts Hitchcockian after the two main characters emerge from a marathon showing of Vertigo (1958) and The Birds (1963) and then, for long moments afterwards, are “trailed” by Bernard Herrmann’s music for that first-named film. Likewise, doubtless even filmgoers who pretend to ignorance of “popular” music cannot help but at least notice the foregrounded snatches of lyrics in the panoply of songs—by artists as stylistically diverse as Radiohead, The Monkees, Paul McCartney, and Bob Dylan—that figure into the soundtrack of Cameron Crowe’s Vanilla Sky (2001).

Vanilla Sky is a Hollywood remake of Alejandro Amenábar’s 1997 Open Your Eyes (Abre los ojos), 12 Monkeys is a variation on Chris Marker’s still obscure 1962 short film La Jetée, and Blade Runner is based on a 1968 novel by Philip K. Dick titled Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The stories of all these, like that of Tarkovsky’s Solaris, which is based on a 1961 novel by Stanisław Lem, are set in “a future” whose advanced technology might boggle the modern mind but whose human concerns are painfully familiar. As has long been standard in science-fiction cinema, certain diegetic noises in these films are evocative of yet-to-be-invented machinery. But these futuristic films’ liberal use of pre-existing music, especially music that audiences not only recognise but likely regard as being somehow “old-fashioned”, suggests subtexts whose prime concerns are based very much in the present.

****

Most of the films whose ambiguities I savour are neither futuristic nor historical; whether old or new, their settings are for the most part contemporaneous with the worlds inhabited by their original audiences. Granted, some of these films’ characters move, with or without knowing it, between various planes of parallel existences. Some of them are depicted as holding credible points of view that grow questionable as their owners areshown to be mentally ill, or living in a dream world, or no longer living at all. Some of them are entangled in extremely “complex” (Staiger) or “perturbatory” (Schlickers) plots whose puzzles may or may not be solved by the time the closing credits roll. In any case, the central characters of what I think are the most resonant examples of reticent cinema are by and large of the type that at least to me seem not much different to myself.

With certain of the especially “perturbatory” films—sometimes described as “mind-game” films (Elsaesser; Buckland) or, less politely, and mostly by German writers, as “mindfuck” films (Beckmann; Menke; Strank)—advance knowledge of what will be surprisingly revealed in the very last moments has the potential to ruin an audience member’s relationship with the entire film (think, for example of M. Knight Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999), David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind (2001), and Alejandro Amenábar’s The Others (2001)). With most examples of reticent cinema, however, there is hardly a need for a “spoiler alert”. What, one wonders, could possibly be said about the final scenes of Last Year at Marienbad or Eyes Wide Shut or Knight of Cups that might “spoil” the filmgoer’s overall experience? It is not that literally “nothing” happens in these final scenes, but what happens seems to be of little consequence, and an imaginative audience member would have good reason to think that if these films were to go on for another several hours the depicted events would be just more of the same.

Whether set in a fantastic future or in a mundane here-and-now, whether dealing with aberrant mental states or trafficking in glimpses of “reality”, the reticent films that for me warrant not just repeated viewings but repeated reflection seem to have in common the fact that they probe deeply, and sometimes uncomfortably, into the nature of consciousness. It may well be that literature in all its forms, as the fiction-writing female protagonist in David Lodge’s 2001 novel Thinks… says in her wrap-up address to a crowd of scientists gathered for a conference on Artificial Intelligence, is “an investigation into what makes us human, and how it is that we know what we know” (316). Yet it seems that some examples of literature, including the screenplays of many a reticent film, go much further than others in their epistemological diggings.

Conclusions…?

In my opening paragraphs I noted the truism that in classical-style cinema almost all of a film’s perceptible elements—including its musical underscore—serve the single purpose of clarifying whatever story the film purports to tell, and I raised questions about how music might function in a film whose mode of storytelling holds not at all to the classical model. There are no simple answers to those questions; like the unhappy families that Tolstoy mentions at the start of his novel Anna Karenina, soundtracks in non-classical cinema veer from the norm in many different ways, and an attempt to reduce these deviations to a short list of “principles”, as Gorbman so neatly did in her landmark account of music in the classical-style film (73), would be an endless, and probably fruitless, task. Still, one can make a few general points that perhaps apply to the entire range of cinema just discussed.

At the risk of seeming tautological, one might say, for example, that music in reticent cinema, like much else in such cinema, is markedly lacking in clear-cut signals. One might say, too, that music in reticent cinema often provides individual filmgoers with frissons of intellectual/emotional stimuli that may or may not be shared with others in the audience. Finally, and at the risk of seeming not just tautological but platitudinous, one might say that music in reticent cinema is by and large consistent with the narratives it accompanies.

Reticent films are sparing in signals yet generous in invitations for speculation. Typically open-ended, their stories perhaps “make sense” enough, but only to those audience members who accept the idea that a film’s “meaning” could well have less to do with what is depicted than what is perceived. The music in the reticent films already mentioned—and in a raft of recent films by such largely “authorial” directors as Darren Aronofsky, Leos Carax, Shane Carruth, Michel Gondry, Michael Haneke, Yorgos Lanthimos, Béla Tarr, Lars Von Trier, and Gus Van Sant—sometimes provides atmosphere aplenty but by and large refrains from explication. By definition, reticent cinema is “held-back” in its storytelling; accordingly, so is its music.

****

This summary, I realise, is hardly as conclusive as the typical ending of a classical-style film. Some readers might find that bothersome, but others might take the comments’ airiness to be apt for the topic at hand. As the theoretical physicist F. David Peat wrote in the final chapter of his 2011 monograph on films that in one way or another deal with the ineffable nature of what it means to be human, “it seems to me entirely appropriate that a book on film and reality should have no real conclusion because that is also the condition of reality itself” (227). To which I would add simply that that is the condition, as well, of many a non-classical film.With its characteristic understatement, Kulezic-Wilson wrote, cinema that is reticently ambiguous, or ambiguously reticent, in effect clamours for “engagement with the text” (62). Perhaps an essay that touches on much but deliberately steers clear of dictum does the same. In any case, I do believe that Danijela would have appreciated this effort.

References

1. Amenábar, Alejandro, director. Open Your Eyes [Abre los ojos]. Sociedad General de Televisión and Les Films Alain Sarde, 1997.

2. ——, director. The Others. Cruise/Wagner Productions and Sogecine, 2001.

3. Aristotle. Poetics. 335 B.C. Translated by Malcolm Heath, Penguin Classics, 1996.

4. Bach, Johann Sebastian. “Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ.” 1732. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis(BWV)/ Bach Works Catalogue, 177.

5. Beckmann, Bennet. “Mindfuck Movies: Filmische Irritationen im US-amerikanischen Gegenwartskino.” 2012. University of Vienna, M.Phil. dissertation.

6. Bergman, Ingmar, director. The Seventh Seal [Det sjunde inseglet]. Svensk Filmindustri, 1957.

7. “Berberian Sound Studio.” IMDb, www.imdb.com/title/tt1833844/?ref_=nm_flmg_t_13_dr. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

8. Booker, M. Keith. Postmodern Hollywood: What’s New in Film and Why It Makes Us Feel So Strange. Praeger, 2007.

9. Bordwell, David, with Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960. Columbia UP, 1985.

10. Brown, Royal S. Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music. U of California P, 1994.

11. Buckham, Paul. “12 Monkeys Soundtrack.” MCA Soundtracks, 1995.

12. Buckland, Warren, editor. Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema. Blackwell, 2009.

13. Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Enlarged edition. Harvard UP, 1979.

14. Crowe, Cameron, director. Vanilla Sky. Paramount Pictures, 2001.

15. Dalí, Salvador. “The Persistence of Memory.” 1931, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

16. Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Doubleday, 1968.

17. Elsaesser, Thomas. The Mind-Game Film: Distributed Agency, Time Travel, and Productive Pathology, edited by Warren Buckland et al., Routledge, 2021.

18. Empson, William. Seven Types of Ambiguity. 2nd ed., Meridian, 1946.

19. Fellini, Federico, director. 8 ½. Cineriz and Francinex, 1963.

20. Fincher, David, director. Fight Club. Twentieth Century Fox, 1999.

21. Flisfeder, Matthew. Postmodern Theory and Blade Runner. Bloomsbury, 2017.

22. Freeman, Philip. “Aristotle Goes to Hollywood.” Aeon, 20 May 2022, aeon.co/essays/how-to-write-a-hollywood-blockbuster-with-aristotles-poetics.

23. ——. How to Tell a Story: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Storytelling for Writers and Readers. Princeton UP, 2022.

24. Gilliam, Terry, director. 12 Monkeys. Universal Pictures, 1995.

25. Godard, Jean-Luc, director. Alphaville. André Michelin Productions and Chaumiane, 1965.

26. ——, director. Masculin Féminin. Anouchka Films and Argos Films,1966.

27. ——, director. Week End.Comacico, Les Films Copernic and Lira Films, 1967.

28. ——, director. Prénom: Carmen. Sara Films and JLG Films, 1983.

29. ——, director. Une femme mariée. Columbia Films, 1964.

30. Gorbman, Claudia. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. Indiana UP, 1987.

31. Gunning, Tom. “The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” Wide Angle, Vol. 8, Nos. 3–4. 1986, pp. 63–70.

32. Haldeman, Charles. The Sun’s Attendant. Jonathan Cape. 1963.

33. Hayward, Susan. Cinema Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge, 2000.

34. Hitchcock, Alfred, director. The Birds. Universal Pictures, 1963.

35. ——, director. Vertigo. Paramount Pictures, 1958.

36. Hock, Tobias. “Film Endings.” Last Things: Essays on Ends and Endings, edited by Gavin Hopps et al., Peter Lang, 2015, pp. 65–79.

37. Howard, Ron, director. A Beautiful Mind. Universal Pictures and Dreamworks Pictures, 2001.

38. Ives, Charles. “The Unanswered Question.” 1930–1935. Southern Music Publishing, 1953.

39. Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism and the Consumer Society.” Postmodernism and Its Discontents: Theories, Practices, edited by E. Ann Kaplan, Verso, 1988, pp. 192–204.

40. Kalinak, Kathryn. Settling the Score: Music and the Classical Hollywood Film. U of Wisconsin P, 1992.

41. Kassabian, Anahid. Hearing Film: Tracking Identifications in Contemporary Hollywood Film Music. Routledge, 2001.

42. Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction. Oxford UP, 1966.

43. ——. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction with a New Epilogue. Oxford UP, 2000.

44. Kubrick, Stanley, director. Eyes Wide Shut. Warner Bros. and Stanley Kubrick Productions, 1999.

45. Kulezic-Wilson, Danijela. Sound Design Is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack. Oxford UP, 2020.

46. Lem, Stanisław. Solaris. MON/Walker, 1961.

47. Lodge, David. Thinks… Penguin, 2001.

48. Luhrmann, Baz, director. Moulin Rouge! Twentieth Century Fox, 2001.

49. Lynch, David, director. Mulholland Drive. Les Films Alain Sarde and Canal+, 2001.

50. Malick, Terrence, director. Days of Heaven. Paramount Pictures, 1978.

51. ——, director. Knight of Cups. Dogwood Films and Waypoint Entertainment, 2015.

52. ——, director. The Thin Red Line. Fox 2000 Pictures, 1998.

53. Marker, Chris, director. La Jetée. Argos Films, 1962.

54. Menke, Sara. “Die Zeit des Mindfuck-Effekts: Zu Wirkungspotenzialen von Echtzeit im Mind-Bender-Film.” Echtzeit im Film: Konzepte–Wirkungen–Kontexte, edited by Stephan Brössel and Susanne Kaul, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2020, pp. 269–85.

55. “Mulholland Drive.” IMDb, www.imdb.com/title/tt0166924/?ref_=nm_flmg_t_42_wr. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

56. “Music from Vanilla Sky.” Reprise/WEA, 2001.

57. Neupert, Richard. The End: Narration and Closure in the Cinema. Wayne State UP, 1995.

58. “Night of Cups.” IMDB, www.imdb.com/video/vi1496757529/?ref_=nm_vi_t_4. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

59. Peat, F. David. A Flickering Reality: Cinema and the Nature of Reality. Pari Publishing, 2011.

60. Piazzolla, Astor. “Suite Punta del Este.” 1982. Azzurra Music. 1999.

61. Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Purloined Letter.” 1844. Great Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe, Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1940, pp. 199–219.

62. Quart, Alissa. “Networked.” Film Comment, vol. 41, no. 4. 2005, pp. 48–51.

63. Quote Investigator. “Films Should Have a Beginning, a Middle, and an End.” “Yes, But Not Necessarily in That Order.” Quote Investigator, 4 Jan. 2020, quoteinvestigator.com/2020/01/04/middle.

64. Resnais, Alain, director. Last Year at Marienbad [L’Année dernière à Marienbad]. Cocinor and Terra Film, 1961.

65. Robey, David. “Introduction to Umberto Eco.” The Open Work, Umberto Eco. Translated by Anna Cancogni, Harvard UP. 1989, pp. vii–xxxii.

66. Sartre, Jean-Paul. Nausea. Translated by Lloyd Alexander, New Directions. 1969.

67. Schlickers, Sabine. “Perturbatory Narration in Literature and Film.” Frontiers of Narrative Studies, vol. 3, no. 2. 2017, pp. 206–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/fns-2017-0014.

68. Scott, Ridley, director. Blade Runner. The Ladd Company and Warner Bros., 1982.

69. ——, director. Blade Runner: Director’s Cut. The Ladd Company and Warner Bros., 1992.

70. “The Seventh Seal.” IMDb, www.imdb.com/title/tt0050976/?ref_=nm_flmg_t_60_wr. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

71. Shyamalan, M. Knight, director. The Sixth Sense. Hollywood Pictures and Spyglass Entertainment, 1999.

72. Staiger, Janet. “Complex Narratives: An Introduction.” Film Criticism, vol. 31, nos. 1–2. 2006, pp. 2–4.

73. Sterritt, David. The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible. Cambridge UP, 1999.

74. Strank, Willem. Twist Endings: Umdeutende Film-Enden. Schüren Verlag, 2015.

75. Strickland, Peter, director. Berberian Sound Studio. Illuminations Films, 2012.

76. ——, director. Katalin Varga. Libra Film, 2009.

77. ——, director. The Duke of Burgundy. Rook Films, 2014.

78. Tarantino, Quentin, director. Pulp Fiction. Miramax, 1994.

79. Tarkovsky, Andrei, director. Solaris [Solyaris]. Mosfilm, 1972.

80. Thanouli, Eleftheria. Post-Classical Cinema: An International Poetics of Film Narration. Wallflower, 2009.

81. Tostoy, Leo. Anna Karenina. The Russian Messenger, 1878.

82. Tykwer, Tom, director. Run Lola Run [Lola rennt]. X-Films Creative Pool and ARTE, 1998.

83. Tynan, Kenneth. “Films: Verdict on Cannes.” The Observer, 22 May 1966, p. 24.

84. Vangelis. “Blade Runner: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack.” Atlantic Records, 1982.

85. Walker, Michael. Endings in the Cinema: Thresholds, Water and the Beach. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

86. Welles, Orson. Confidential Report (a.k.a. Mr. Arkadin). Filmorsa and Mercury Productions, 1955.

87. Zborowski, James. “Review of Philippa Gates and Katherine Spring Resetting the Scene: Classical Hollywood Revisited.” Screen, vol. 63, no. 2, 2022, pp. 405–07. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjac036.

Suggested Citation

Wierzbicki, James. “Music in ‘Reticent’ Cinema.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 27, 2024, pp. 189–205. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.27.17

James Wierzbicki is an essayist and cultural historian. Before embarking on an academic career (teaching musicology at the University of California-Irvine, the University of Michigan, and the University of Sydney), for more than twenty years he served as chief classical music critic for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and other American newspapers. His books include Film Music: A History (2009), Elliott Carter (2012), Music in the Age of Anxiety: American Music in the Fifties (2016), Terrence Malick: Sonic Style (2019), and When Music Mattered: American Music in the Sixties (2022).