“X” Marks the What? “Cross Influence”, Extractivism, and the Labours of Moving Image Excavation in Harun Farocki’s The Silver and the Cross (2010)

Lawrence Alexander

[PDF]

Abstract

Harun Farocki’s 2010 video installation The Silver and the Cross (Das Silber and das Kreuz) presents a “soft montage” of Gaspar Miguel de Berrío’s 1758 painting of the Cerro Rico Mountain and surrounding city of Potosí in contrast to contemporary footage of the same region shot in present-day Bolivia. Questions of extraction (or, more specifically, extractivism) and histories of representation abound in relation to intersecting networks of capitalism, Christianity, and colonialism on the Latin American continent—andthe depredations of the imperial silver mining trade in particular. This article situates Farocki’s moving image practice within the broader media and technological genealogies and logics of extractivism. The importance of “soft montage” or “cross influence”, a signature of his later œuvre, to this kind of investigation is paramount. Farocki’s analysis sees the juxtaposition of close-up, tracking shots, and static shots of Berrío’s landscape to dwell on the class and racial hierarchies that might otherwise fall below the register of visibility while regarding Berrío’s eighteenth-century rendering. In a mode of performative practice that makes a plea for the archaeological survey of images in general, I contend, Farocki enlists the techniques of cinematography to conduct a forensic examination of superficial representation: “X” marks the spot.

Article

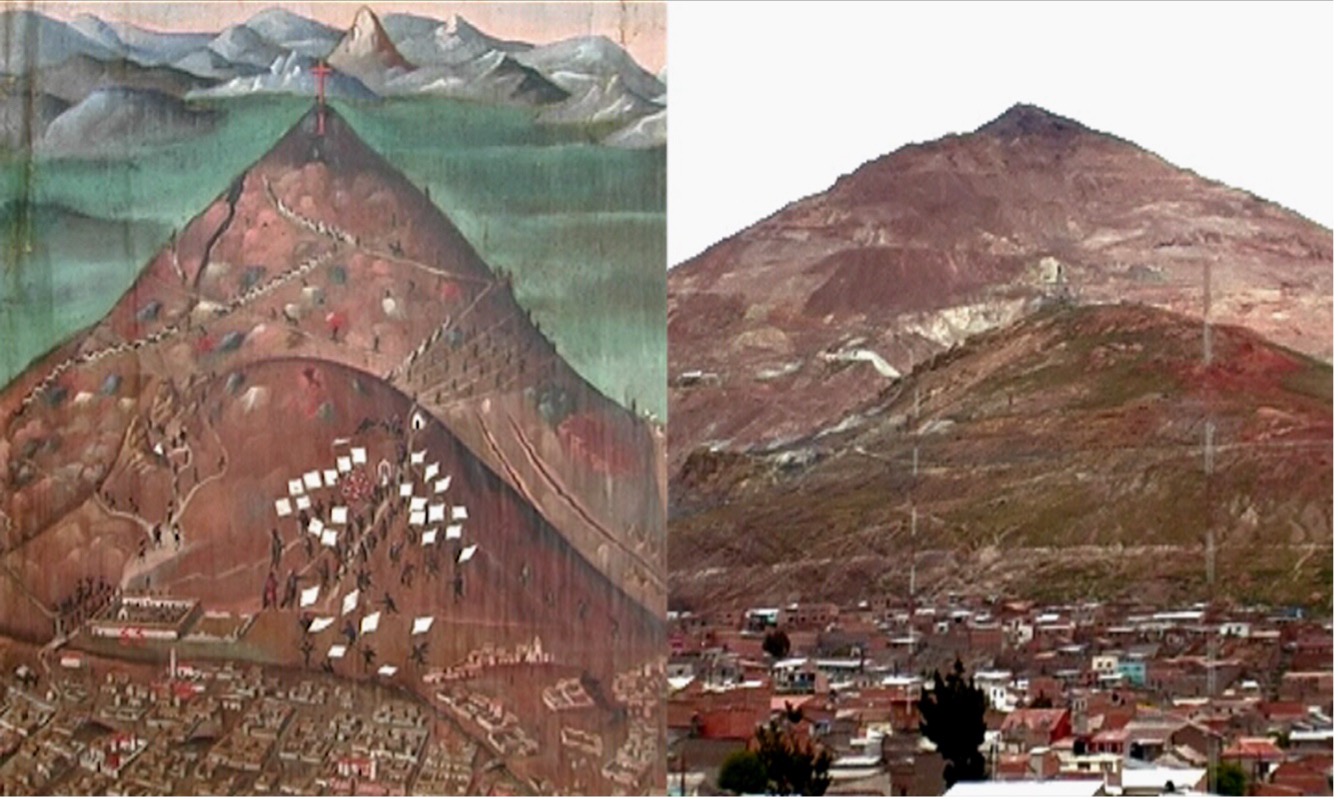

Figure 1: Farocki compares the eighteenth-century rendering of Gaspar Miguel de Berrío’s

Descripción del Cerro Rico e Imperial Villa de Potosí (1758) to contemporary footage of the mountainside.

Photo: The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010.

In his 2010 video installation The Silver and the Cross (Das Silber and das Kreuz) the German documentarian, essay filmmaker, and installation artist Harun Farocki performs a forensic reading of Gaspar Miguel de Berrío’s 1758 painting of the Cerro Rico Mountain (in Quechua, known as Sumaq Urqu) and the surrounding city of Potosí. The installation uses “soft montage”, a hallmark of Farocki’s later œuvrethat consists of two image tracks shown together in parallel or side-by-side. Also known by Farocki as “cross influence”, this technique is deployed in The Silver and the Cross to juxtapose various shots of Berrío’s painting—both with each other and in contrast to contemporary video footage of the same region in present-day Bolivia. As Farocki limns the contours of the filmed and painted landscape, he dwells on the class and racial hierarchies that might otherwise fall below the register of visibility while regarding Berrío’s eighteenth-century rendering.In this article, I argue Farocki’s intermedial moving image practice reprises his abiding interest in the connections between film history and histories of labour. Specifically, the extractivist mining of silver and the dominations of worker and landscape it entails are imbricated in a broader history of colonial violence and genealogies of moving image reproduction. The importance of “cross influence”to this kind of investigation is paramount: the compositional form of two-channel video installation that entails a crossing between image flows to frame the archaeological and the art historical together—spanning surfaces and temporalities—organised across space and through time. This arrangement provides Farocki with a relational model that both encompasses and cross-references the workings of an extractivist imperial economy and Farocki’s own media-archaeological practice to excavate the superficial representation of Berrío’s painting. In a mode of performative practice that makes a plea for the archaeological survey of images in general, Farocki enlists the techniques of cinematography to conduct a forensic examination of the surface: “X” marks the spot. I contend this practice of remediation places the installation’s images in a dynamic relationship with each other to animate the embedded and intertwined media genealogies implicated in broader histories of colonial violence, traces of which are still borne by the Potosí mountainside today.

Questions of extraction (or, more specifically, extractivism) and histories of representation abound in relation to intersecting networks of capitalism, Christianity, and colonialism on the Latin American continent—and the depredations of the imperial silver mining trade in particular. Moreover, given the criticism by Bolivian artists of The Potosí Principle exhibition to which the installation contributed, this article considers the context of the installation’s production and exhibition. Approaching the preeminent German practitioner’s sole work in and about Latin America, I examine the extent to which The Silver and the Cross both interrogates and rehearses the “overlap of hegemony and image production between Latin America and Europe” that forms the double focus of the installation and The Potosí Principle exhibition (Haus der Kulturen der Welt). While there exist accounts of the controversy surrounding the exhibition and its criticism by the Andean Colectivo (Alberro; Rivera Cusicanqui), these debates have to date not been brought to bear substantially on an analysis of Farocki’s video installation. In the last part of the article, I consider the physiognomic logic of Farocki’s video investigation that reads Berrío’s landscape at or as face value. This focus on the face of the Cerro Rico and Potosí combines the poststructuralist thought of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari with the Indigenous perspective of Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui. My analysis here accordingly performs a certain crossing of its own by combining close readings of Farocki’s video installation with requisite attention to the context of its production, exhibition, and reception in Europe and Latin America.

Beyond The Potosí Principle: Context and Controversy

In light of these intersecting scholarly and curatorial contexts and, in particular, in the spirit of a special issue on the theme of external perspectives approaching Latin America, it is especially critical to account for the circumstances of the installation’s development and exhibition. The Silver and the Cross was commissioned as part of The Potosí Principle, an exhibition shown first at Madrid’s Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in 2010, before travelling to Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt in the same year, and finally, Museo Nacional de Arte and Museo de Etnografía y Folklore, La Paz in 2011. During the project’s development and exhibition, however, The Potosí Principle came under scrutiny from an independent group of Bolivian artists known as “El Colectivo” (“The Collective”). These concerns can also be situated in dialogue with more recent scholarly discourses on extraction and increased awareness of Indigenous thinking that have gained prominence in the fifteen years since the installation was first exhibited (and the decade since Farocki’s death in 2014). Since 2010, a significant amount of scholarly attention has been paid to the connections between cinema and extraction; above all, by Priya Jaikumar and Lee Grieveson and by Brian Jacobson. These accounts draw on decolonial frameworks developed by the work of Latin American scholars such as Walter Mignolo and Aníbal Quijano that decentre European perspectives and the colonial epistemologies that constitute the discursive construction of history and memory. And while the primary object of our attention and analysis will remain Farocki’s installation and not the wider exhibition and the controversy it generated, the latter provide crucial context to a reading of the former that must not be overlooked. Otherwise said, it is not in the remit of this article to provide a comprehensive account of The Potosí Principle’s exhibition and its criticism by Bolivian and Indigenous artists (Alberro’s article already serves this purpose well). An awareness of this controversy and an acknowledgement of critical Indigenous voices such as Rivera Cusicanqui’s writing on El Principio Potosí Reverso, a counter-catalogue developed in response to the original exhibition, are, however, of vital importance to the analytical work I seek to perform on Farocki’s practice.

Curated by two Germans and a German-Bolivian curator, Andreas Siekmann, Alice Creischer, and Max Jorge Hinderer, The Potosí Principle sought in the iconography of Spanish Imperialism and, above all, the baroque visual art of the Counter-Reformation, an originating structural logic for the development of the world-system of global finance capitalism. This trajectory posited a “genealogy” that extended from the long sixteenth century to the “essential features of neoliberal globalization and contemporary art” (Alberro 19). Here “principle”, or principio in Spanish, has a double meaning, as both a guiding or structural logic and as an origin. To a certain extent, this curatorial credo has been corroborated by subsequent scholarship on histories of extraction and their enduring significance for today’s global economy. For instance, Martín Arboleda has argued that exploring “the colonial histories and geographies of the last six centuries reveals how natural-resource frontiers are internally related to the constitution of the very fabric of modernity” (28). Moreover, he notes that absent the “fabulous material wealth” generated by the silver mines of Potosí (and sugarcane plantations of Brazil), “the cultural, artistic and political efflorescence that characterized the so-called Golden Century of the Habsburg dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula would have never existed” (28). With a particular focus on the relation of extraction to media genealogies, Jaikumar and Grieveson similarly observe that silver mining was “integral to the early global system of capitalism moving matter from the new world to the old, before becoming part of the money supply circulating globally” (“Introduction” 10).

For his part, Alberro acknowledges the good intentions of the exhibition’s curators, which eschewed “traditional object-oriented curatorial practice to ask how their exhibition might open history to subjugated knowledge and alternative interpretations” (19). However, this curatorial ethos failed to subvert or surrender the hegemonic and asymmetrical position of Europe or the “North Atlantic art framework” in its representation of Indigenous and colonised populations (Alberro 26). Where Indigenous epistemologies were addressed, Alberro contends, they were demeaned as “anachronistic, quaint, or peripheral” (26). According to this account, the exhibition’s curators tended not to include works by Andean cultural producers for fear of setting a folkloric and affective tone as opposed to framing a critical and intellectual engagement with the material exhibited. As a result, the exhibition instead used “mostly foreign artists and creative Western production and exhibition techniques to speak for [Andean communities], largely neglecting the persistent asymmetries in this presentation” (Alberro 29–30).

Moreover, the exhibition’s insistence on the violence and subjugation meted out to Indigenous populations by their Spanish colonisers undervalued—or ignored—the “semiotic resistance” asserted by the subjectivity of Andean communities: what Alberro identifies as an “underlying notion that European culture had entirely subdued and destroyed Indigenous ways in the Andes” (27). Critics like Rivera Cusicanqui, who had initially been invited to work with the project’s curators, criticised the museal exhibition of these artefacts shorn of their local context as “a powerful force of de-territorialization and loss of meaning”. Ironically, despite the stated intentions of the exhibition’s curators, “[w]hat paradoxically persists”, Rivera Cusicanqui asserts, “is the act of expropriation, the colonial emblem of financial accumulation; the circulation of the Andean baroque as a spectacle and as a commodity of high symbolic and monetary value.” This characterisation also suggests a logic of extraction whereby Andean art does not “circulate” freely in every instance or in every direction. A most egregious example of this deterritorialising dynamic is the fact that the Berlin Ethnological Museum refused the curators’ request to lend a Bolivian artefact (a recording device known as a quipu or khipu) from their “enormous” collection to be included as part of the exhibition when it travelled to the Bolivian National Museum despite permitting loans to European museums (Alberro 28). These circumstances give the impression that the curators’ critical sensibility was not one applied to their own practices. And while the exhibition guide’s entry for Berrío’s painting exhorts, “you are now aware that every commodity and every investment bears and simultaneously conceals this form of [primitive] accumulation” (Potosí Guide), as Rivera Cusicanqui has suggested, this guidance falls short of acknowledging its own rehearsal and reproduction of extractive dynamics.

Suffice it to say the circumstances of the exhibition and the resulting controversy are complicated. It remains possible to discern a curatorial attempt to trace a critical genealogy of extractive capitalism and its concomitant “world-system”—arguably from a decolonial perspective—that is nonetheless implicated in the extractive deterritorialisations it might otherwise target for criticism. And while it remains of utmost importance to emphasise the Indigenous and Andean voices of dissent and criticism levelled at the exhibition, it also appears that many of the curatorial “principles” that underpinned the project share much in common with the convictions of scholarship on the logics of extraction and their relation to historical and contemporary media. However, it must also be made clear that this scholarship demands a “disciplinary unsettling” that “reformulates” global media studies (Jaikumar and Grieveson, “Media” 2). Moreover, Jaikumar and Grieveson insist that such work “be compelled to question Western epistemological frameworks that remain culpable in enabling and sustaining the planet’s instrumentalization” (“Media” 2). Elsewhere, Jaikumar and Grieveson sound “an opening caution regarding media histories of extraction […] that such narratives should not lead us to reinforce, yet again, Western Europe and the United States as primary historical actors of consequence” (“Introduction” 24). It is perhaps on these terms that the original exhibition falls short of the imperatives that have since driven scholarly attention to the historical and contemporary modes of relation that embed media in forms of economic and cultural extraction.

In any case, situating the exhibition in the context of these critical and scholarly discourses provides crucial context for thinking about Farocki’s position as a German filmmaker who produced an installation for The Potosí Principle alongside a majority of non–Latin American practitioners. As we shall see, Farocki seeks to excavate and reveal what lies behind the silent surface of painted representation; he points out and indexes with an “invisible” authorial hand. And yet, a critical lamentation of silence by European philosophy in the face of genocidal violence nonetheless risks reproducing the wider curatorial decision to forego the inclusion of oral histories from Andean and Indigenous perspectives. While it is worth noting Farocki’s own heritage, having been born to an Indian father and German mother living in the occupied Sudetenland a year before the end of the Second World War, this author recognises the limitations of accounting for Farocki’s positionality on identitarian grounds. The following section will pay close attention to the logics of extraction critiqued by Farocki’s video installation, a forensic examination of Berrío’s painted surface, while also considering the extent to which Farocki also elides or overlooks Indigenous experiences in his work.

Excavation and Extraction

The “heart” of the colonial silver trade, Potosí was home to one of the first mints established in South America by Spanish colonisers. At its peak, the city had more inhabitants than Paris or London at the time, becoming the fourth largest city in the world. By the time of Cervantes, the city had become a byword for extreme wealth as is evident from the expression valer un Potosí: meaning to be worth a fortune. The focus of Farocki’s video installation on this mining community traced across particular traits of a painted landscape provokes questions of excavation and extraction, as well as coinage and the monetary value of silver taken from the natural environment to fund the colonial expansion of the Spanish Crown. As the installation’s voiceover describes, the plunder of natural resources and the development of industrial-scale extraction stimulated a flow of capital that reached across the world. In Marxian terms, this system of “primitive accumulation” would pave the way for a global system of financial capital that is familiar today. To a broad extent, this narrative follows that of The Potosí Principle curators who sought to expose or make visible the workings of accumulation and exchange that were borne yet concealed by “every commodity and every investment” (Potosí Guide 10).

More specifically, these practices can be understood as a preeminent form of extractivism entailing the removal of “large quantities of natural resources that are not processed (or processed only to a limited degree), especially for export” (Acosta 62). This mode of extraction and export rests on forms of environmental and racial violence that provide the conditions for raw materials to be integrated into broader, global economic structures that attribute and accumulate value. As Kathryn Yusoff has noted: “The motivation of colonialism was as an extraction project. The consequence of this formation of inhuman materialism was the organization of racializing logics that maps onto and locks into the formation of extractable territories and subjects” (88). In the The Silver and the Cross, these dynamics and the scalar exchange they activate (between global and local, economic and ecological, micro and macro registers) are transposed to the medial reproduction of Berrío’s eighteenth-century painting in Farocki’s video work, which often focuses on minute details of the painted canvas.

In other words, Farocki’s installation seeks to excavate that which is hidden by the surface effects of Berrío’s painting, an artwork that is itself symptomatic of what Farocki describes as the silence of the European Enlightenment’s philosophers in the face of slavery and colonialist depredations. According to the voiceover, the veneer of “science, world trade, and capital in place of simple robbery” conceals the conditions of forced labour and the deaths of many Black and Indigenous workers that produced the riches of the silver trade. Farocki thus seeks to provide “counterimages” to the omissions or “silences” of Berrío’s representation and of Enlightenment philosophy. His visual analysis of the painting and its juxtaposition with the scenes of modern-day Potosí (shot in the late 2000s) establish the mountainside as a forensic site for the investigation of colonial crimes, the effects of which are still being uncovered by archaeologists today.[1] In this vein, Kodwo Eshun has linked this analysis to Eyal Weizmann’s conception of the “forensic process” and the “thresholds of detectability” examined in the practices of the Forensic Architecture collective. This formulation rearticulates what Nora Alter terms Farocki’s attention to “the im/perceptible at the margins of vision or cognition” in his modus operandi (20). However, while it is clear that Farocki seeks to render visible those overlooked by the record of colonial history, silent figures unable or not permitted to speak for themselves, he does so by opening up a dialogue between the images rather than through a concerted attention to the oral histories of Andean populations actively omitted by the exhibition’s curators.

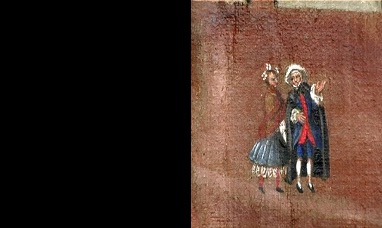

Figure 2: “On the mountain, the cross. In the mountain, the silver ore.”

The installation’s voiceover establishes its cross influence between signifying regime and raw material juxtaposed across two close-ups. Photo: The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010.

In The Silver and the Cross, Farocki applies the techniques of cinema—static shots, tracking shots, close-ups, and voiceover—to parse the surface of painterly representation.His analysis begins with a juxtaposition by soft montage of two images—or counterimages—from Berrío’s painting: a cross protruding above the ground atop the mountain and the dark crack in the surface of the mountainside like a slash cut through the canvas, penetrating the ground to expose what lies beneath. Farocki’s voiceover then recalls the legend of the Indigenous man Diego Huallpa who is said to have discovered a vein of silver in the cave on the traditional territory of the Charcas and Chullpas people by accident after lighting a fire there in 1545. The Promethean legend of a man lighting a fire only to discover silver as well as the introduction of fire to a cave-like topographical site is already suggestive of Plato’s cave allegory: yet another principio—both originary space and guiding principle for representational thinking. The play of light and shadow in the darkness of the mines is further suggested by the depicted sale of candles at markets, which Farocki dwells on in close-up moments later, with the mineworkers pictured carrying a candle attached to their thumb on their way to work. The site of the cave as a space for flickering images projected by firelight is reminiscent of the cave not only as an allegory for representation in general but also traces a media genealogy that extends much further back in time as a “pre-history” of cinema.

Figure 3: Workers painted as featureless black figures buy candles at the market before setting off for work in the mines. Photo: The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010.

The installation, like so much of Farocki’s work, can thus also be read as a self-reflexive meditation on image-making processes in general and the intertwined relation between genealogies of film, photography, and other representational forms, most notably painting. In particular, the implicit connection between the mining of silver and the processes of photochemical reproduction integral to the development of analogue filmmaking is situated within a broader history of colonial and capitalist expansion and the labours that sustained it. Farocki’s moving image practice also suggests that film technology can be used to perform a thoroughgoing analysis—even an excavation—of those histories and their superficial layers of pictorial and historical representation. This accords with what Alter describes as Farocki’s “method of close hermeneutic and even deconstructive image analysis” that “remained constant throughout his career” (19). Produced in 1758 and taking two years to complete, Berrío’s painting comes to figure in Farocki’s analysis as a kind of anachronism in a double sense: on one hand, at the time of painting, the extraction of silver had long since passed the peak it had reached in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The reserves of silver ore that had “flowed” so abundantly eventually became harder to access and squabbles between the Spanish settlers (featured in close-up at intervals by Farocki) began to break out. On the other hand, the painting comes much earlier than the invention of photographic and filmic recording as a vehicle for the evidentiary indexing and documentation of the landscape: a photochemical process that relies on the exposure of silver halide crystals for the development of resolution and detail. In this vein, both the extraction and amalgamation of silver ore using the catalyst of mercury and Farocki’s excavation of the painted representation of the same processes using a video camera suggest a kind of exposure or transferral of the inside to the outside that is analogous to processes of photochemical reproduction and photographic negativity.

Or perhaps this sense of anachronism is overblown. As Siobhan Angus claims in Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography: “When we read the history of photography through the lens of silver, Potosí is a precondition for the emergence of photography” (75). Ariella Azoulay, who Angus cites, likewise locates the emergence of photography in the fifteenth-century conquest of the Americas rather than the nineteenth century (75). In this sense, Potosí stands for another principio, a precondition for the development of photographic reproduction and a concomitant image economy that is itself analogous to the circulation of silver. That these same processes have, in turn, been theorised by Alessandra Raengo in relation to historical and enduring structures of race formation further complicates the metonymic imbrication of extraction and exposure in The Silver and the Cross. As Raengo argues, “the process of racialization is analogous to the photographic process of photochemical fixation” (11). The cross influence of Farocki’s installation thus serves to historically situate the ontological status of technological processes of image reproduction and their relation to the organisation of workers according to racial hierarchies that are equally highly constructed. Moreover, given that Potosí stands for a system of accumulation based on the expropriation and displacement of Indigenous populations and their forced or waged labour alongside enslaved African and Chinese workers (Alter 108–09), Raengo’s analysis is instructive for analysing Farocki’s work in The Silver and the Cross and the association of binary systems of negation (and negativity) that demarcate non-white bodies in representational space.[2] Berrío’s painting comes, then, in a sense too early and too late: much later than the Cerro Rico’s heyday, the colonisation of the Americas, and the conditions that enable the development of photography, but much earlier than the application of film to harness this analogous photochemical process for the purposes of explorative documentation.

Moreover, the mutual imbrication of the extractive mining economy and the history of photography is further complicated by the compositional form of cross influence that structures Farocki’s video investigation across two channels. Tellingly, Farocki describes this hallmark of his later practice using a petrochemical analogy:There is succession as well as simultaneity in a double projection, the relationship of an image to the one that follows as well as the one beside it; a relationship to the preceding as well as to the concurrent one. Imagine three double bonds jumping back and forth between the six carbon atoms of a benzene ring; I envisage the same ambiguity in the relationship of an element in an image track to the one succeeding or accompanying it. (“Cross” 70)

Not only does this framework suggest a molecular model for the volatility of the relations between images concatenated in time and space (succession and simultaneity) by soft montage. Farocki’s chosen image also indicates his conception of the moving image artwork, a processual endeavour, as analogous to the chemical and labour processes of industry. It is the workers that are subordinated by these industrial processes given such granular attention by Farocki that the following section will examine.

Workers Leaving the Chapel: Processional Politics

I will now consider in detail an early sequence that articulates the relations of workers and their representation in congregational and processional formations. Following the early “establishing shots” of the mountaintop and cross, the installation proceeds to dwell on what Farocki calls “processions” of figures up and down the Cerro Rico mountainside. This movement of bodies encompasses both the religious, ceremonial, and ritual dimension of congregational scenes as worshipers arrive at and depart from a chapel and the more profane scenes of them leaving or arriving to work. Indeed, the chapel here serves both as an analogous space of enclosure to the workplace of the cave or mine, as well as the factory and the prison targeted elsewhere in Farocki’s œuvre, and to the cinema as a site in which the conditions of domination that structure working relations are extended to would-be spaces of leisure.[3]

Figure 4: Workers leaving the chapel: a procession of figures traced downhill by a tracking shot that also marks the second axis of a cross between the two channels of Farocki’s installation.

The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010. Screenshot.

The processional character of the workers’ movement is first considered as Farocki notes the trajectory of the Indigenous workers, visible only as featureless black figures against the reddish hue of the mountainside, ascending to their workplace of the silver mines. A tracking shot in the left-hand frame then traces another movement (diagonally uphill from right to left) of figures toward what looks like a chapel, implying an analogous form of social organisation to the working conditions of the mine. The left-hand frame then cuts to black while on the right, another procession is visible as this time the tracking shot moves “downhill” and follows another procession diagonally from right to left. The soft montage or cross influence of these two tracking shots traces a cross that spans the broader field of vision of the two video channels and thus works to perform another kind of crossing. In the wider context of The Silver and the Cross, this camera movement might be read as tracing the “sign of the cross”, albeit at an oblique angle. This sequence thus serves to concatenate a range of different crosses and crossings that include both the perpendicular intersections of vertical and horizontal axes in the Roman cross and the diagonal crossings that form an “X”. In the context of the Spanish conquest and colonisation of Latin America, the latter combines these functions (both “cross” and “X”) in the form of the Burgundian cross: an emblem not only of European dynastic power, but also of the Spanish Crown’s mission as a Christianising colonial force. Moreover, by tracing an “X” in the field of vision and crossing the two channels of his video work Farocki indicates what he conceives of as a space for excavation and media-archaeological enquiry: “X” marks the spot.

Farocki then follows “a further procession” of Spaniards heading toward a reservoir where the white figure of a hunter can be seen shooting at a bird. The focus of the “X” is thus associated with the crosshairs of the hunter’s rifle and the implication of the shot-countershot structure of oppositional montage that is organised spatially in the installation form of “soft” montage. The operation of the “X” in The Silver and the Cross thus reaches across multiple scales and semiotics that intersect in the practice of what Akira Lippit calls an “archaeology of the surface”, in which “X” operates “as the sign for an imaginary topography deep beneath the signifier” (54). Lippit’s exegesis of the functions of “X” is worth considering at length:

Simultaneously known and unknown, “x” eludes the economy of signification, generating a phantasmatic signifier without signification or, conversely, a full signification with no signifier. “X” can be seen as the master signifier for no signification, for deferred or postponed, overinscribed and erased signification. […] Both a letter of the Roman alphabet, a number, and a figure, a graphic symbol, “x” operates within various economies of signification and meaning at once, never reducible to one system or another, to language or image. A trace: an erasable sign and sign of erasure that erases as it signs and is in turn erased already. (54)

In the context of the Potosí silver mines and their status—according to Angus (75)—as the precondition to the subsequent emergence of photographic reproduction, “X” as the sign of a topographical depth-model that nonetheless relies on the signifying surface is useful for thinking about how the external perspective of Farocki’s installation is inscribed across the visual field of its two channels. While Farocki does not appear in The Silver and the Cross (unlike a number of his works where he figures as “author-as-receiver”), the cross as a trace that signs and erases at the same time is apposite to his own ambivalent authorial status between intervention and disavowal, absence and presence: what Volker Pantenburg calls “the hinge and relay between production and reception” (51). This gesture is, then, perhaps a knowing play on the “invisible hand” of the market conceived of by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations and mentioned by the Potosí Principle exhibition guide in the entry for Farocki’s installation (10). The “invisible” hand of the artist here works to render visible the social and economic relations that constituted the reality of historical experience of the miniature figures depicted at—and indeed beyond—the margins of perceptibility in Berrío’s painting. And yet, the marking of the “X” as a movement that signs and “unsigns”, inscribes and erases at once, is also one that underscores the metonymy whereby the silver betokened by Potosí more widely comes to stand in for photography. It alludes to a photographic process—and product—that nonetheless occludes the labour relations of its own production. As Angus asserts: “Silver appears and disappears in the photographic developing process: its capacity to move forms the print. Trying to ground photography in the depths of the mine […] is an incomplete gesture” (105).

The “crossing” of silver here works to index both the mobility of capital and the forced movement of people to constitute the labour supply across the Americas and the Atlantic. The recurring processional motif of bodies in motion is also reminiscent of Farocki’s earlier essay film Workers Leaving the Factory (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik, 1995) and the installation Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzehnten, 2006) as well as the project Labour in a Single Shot (Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit, 2011–14), all of which take the flight of workers from the workplace as paradigmatic for thinking about histories of both labour and film. In this context, the processions of workers in The Silver and the Cross might figure as a pre- or proto-industrial iteration of workers leaving the Lumière Brothers’ factory: Farocki’s (literal) point of departure for his earlier films. Viewed in this light, the work’s concern with working activity—waged or unpaid, that which might remain hidden or unseen—connects these kinds of procession with historical processes more broadly and the processual production of film images more specifically. In The Silver and the Cross, Farocki’s camerawork animates the still images of Berrío’s painting and imbues them with motion in a proto- or paracinematic fashion. As Thomas Elsaesser has suggested, this technique also brings the viewer closer to the black figures of the labourers, “making us part of the different crowds depicted” (Elsaesser and Alexander Alberro 5). But unlike the other racial and social classes of traders, artisans, and Spanish colonisers who are depicted with a facial complexion in minute detail, these workers remain figures without a face. Farocki’s use of the close-up and tracking shot thus allows his viewer to draw nearer to the procession of these figures not to show the face of the other but to excavate the structures of a politics that is based on negation, exclusion, and crossing out. This “gesture” however inadequate or incomplete, to use Angus’s terms, nonetheless serves to emphasise what she calls “the unresolved tension in photography: between the world of the surface and the labor that makes the world, labor that is often underground or out of sight” (104).

Figure 5: Meanwhile, the faces of white Europeans are captured in minute detail.

Photo: The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010.

Landscape at Face Value

What is the significance of the facial features bestowed to certain figures and not to others in Berrío’s painting according to their position in a racial hierarchy that configures the conditions of forced and waged labour? In the final sections of this article, I will consider the physiognomic logic that is instrumental to Farocki’s forensic analysis in The Silver and the Cross. The Potosí Principle exhibition guide’s entry for Berrío’s painting that hangs opposite Farocki’s video investigation notes: “You don’t see any mines in the mountain, you see the investments and the infrastructure: dams, canals, and refineries. But you see only a few workers in the city, as if this picture were also a character mask” (10). The Marxian term used repeatedly by the curators refers to the collective social expression at a particular historical moment that conceals the underlying conditions that support an economic system: in this case, a representation of the forced labour of displaced Black and expropriated Indigenous populations. Here too there is a suggestion of the “X” sign that marks only to dissemble. There is something of a figure-ground slippage and modulation between scales in the attribution of a social mask that stretches across Berrío’s landscape. It is then as a surface of facial representation, a “mask” to be lifted, that we might engage with the rendering of the Potosí mountainside; the painted canvas magnified and animated by the techniques of cinematography might resemble an organic or pellicular surface beneath which veins of silver and conditions of exploitation are concealed.[4]

Writing on “Faciality” in A Thousand Plateaus,Deleuze and Guattaridevelop a physiognomic approach to elaborate on the embedded character of the face in a wider social reality since “concrete” faces are not produced in the same way by every system of sociocultural meaning. The representation of a landscape on a canvas or screen thus has the same flattening function as faciality, reducing to a surface of meaning that which had belonged to another “multidimensional” order (Deleuze and Guattari170). The reduction of topography to a collection of traits, lines, and contours, which can be read in a physiognomic way equally corresponds to this logic that extends far beyond the face proper to cover surfaces, objects, and indeed landscapes. On the one hand, this correlation implies an anthropomorphic image of the natural environment: how topographic features appear and are rendered in two-dimensional representational space. Deleuze and Guattari thus claim that architectural features—“houses, towns or cities, monuments or factories”—are configured “to function like faces in the landscape they transform” (170). Painting meanwhile positions “landscape as a face” while “close-up in film treats the face primarily as a landscape; that is the definition of film, black hole and white wall, screen and camera” (170). As such, Deleuze and Guattari destabilise the figure-ground character we might associate with the composition of face and landscape along with the representational and orientational binaries of portrait and landscape. Approaching Farocki’s treatment of Berrío’s landscape in this context, we might consider the painting as a surface that bears ciphers or encoded meaning in the tradition of portraiture. Indeed, Alter likens Farocki’s aesthetic practice to Theodor W. Adorno’s notion of the Vexierbild or “picture puzzle” insofar as it is the artist’s “project to reveal both sides of the puzzle” (20). The slippage between face and landscape implied by Farocki’s meticulous examination of the canvas and its juxtaposition with shots of present-day Potosí while revelatory might also encourage the critical capacities of his viewer to scrutinise the “face value” of superficial representations along with the socio-economic relations that undergird them.

While the “X” here serves as a cipher for archaeological practice, artistic composition, and industrial process, held together in the metonymy and polysemy of Farocki’s work, it also stands for a political economy and mode of social organisation predicated on exclusion. Indeed, Deleuze and Guattari also identify a system in which facial identity is constructed and imposed on an “individual” according to a binary schema, always necessarily in a “biunivocal relationship” with another, nonconforming, divergent face to single out those racial, gender, or sexual identities that differ from the universal image of the white, European male or “Christ-face” (178). The face is not just another part of the (whole) body, but a system of ordering people and worlds—polities and, above all, the state—according to a series of branching negations (not-male, not-white, etc.) that distribute subjectivity in line with contingent formations of power. The idea that faciality “propagates waves of sameness” thus might apply to the history of colonial expansion and missionary Christianity over the course of modernity as Deleuze and Guattari describe: “From the viewpoint of racism, there is no exterior, there are no people on the outside. There are only people who should be like us and whose crime it is not to be” (178). As we have observed, this binary logic between the facial representation of white and non-white bodies comes into sharp relief in Farocki’s close-up of Berrío’s canvas and a juxtaposition between the facial features of the white, European, and Christian colonisers and the faceless, featureless black figures of the labour force.

A Ch’ixi Complexion?

While the Deleuzo-Guattarian model of faciality is certainly apposite, I do not wish to retrench a Eurocentric perspective on the history of the Potosí mountainside with this recourse to the French poststructuralists. On the contrary, affinities can be found between this framework and the work of Rivera Cusicanqui in her criticism of The Potosí Principle project from an Indigenous perspective as she conceives of the mountainside in explicitly facialised terms. For example, Rivera Cusicanqui contrasts the “patriarchal and totalizing dimension in the right side, the white and masculine face of this book” to “its left face—dark and feminine—[that] internally traverses the lived space of the Andean geography in the cycle of festivities that mark turning points in time/space (pacha)”. While Rivera Cusicanqui regrets that “the only recognition Europeans have of our culture seems to be expressed either in terms of folklore or misery”, she asserts that “the whole system of colonial transferals and relocations were experienced as an overlapping space of negotiation and resistance, which took place in and through the market”. There is, then, a complex double vision articulated from her perspective situated in Indigenous understandings of the “semiotic resistance” to colonial domination. Looking again at the processional motif marked out by the sign of the cross, it becomes possible to discern what Rivera Cusicanqui describes as “the itineraries of ritual libations, dances, and chants in the routes that connect the wak’as with the centers of power in successive historical horizons of signification and territorialization”. The very fact that our attention is trained on these ritual itineraries grounds the critical, external perspective of Farocki’s analysis and brings it back down to earth.

In turn, the proximity of our focus to those on the ground might thus allow us to see what Rivera Cusicanqui calls “the inscription of the sacred in the materiality of the landscape” alongside the domination of colonisation and Christianisation. A “dialectic without synthesis”, the Andean conception of “a different configuration of collective subjectivity, which we have termed as a ch’ixi subjectivity” is conceived of as “an active recombination of opposed worlds and contradictory meanings, which forms a fabric in the very frontier of these antagonistic poles”. Without equating this form of Indigenous subjectivity with a European aesthetic paradigm, the resonances of this description with montage in general and cross influence (soft montage) in particular are hard to overlook. Moreover, with a meaning approximate to “mottled” or “stained”, the notion of ch’ixi thus suggests both a sense of blemished complexion in the representation of the mountainside landscape as a corporeal, facial surface while also suggesting the “recombination” or chiasmus of Farocki’s two-channel cross influence. To be sure, Farocki’s participation in The Potosí Principle exhibition implicates him in its “asymmetrical presentation” of deterritorialised artefacts and commissions for predominantly non–Latin American artists. And yet, the compositional form of his video analysis can also be read alongside forms of Indigenous knowledge that provide a means of situating Farocki’s work remarkably closer to Andean perspectives on the region’s history and memory than his external position would otherwise suggest.

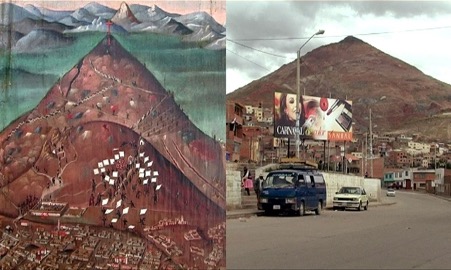

It is perhaps not until the final shot of The Silver and the Cross that the correlation of face and landscape is made explicit within the same compositional frame. The image track first shows two parallel shots of the mountain: on the left-hand side, Berrío’s painting and on the right, a shot of the mountainside in 2010. The voiceover notes: “Today, archaeology can already determine from the remains of long-dead people whether they were able to feed themselves adequately or suffered from deficiencies. After many centuries.” This reference to the archaeological investigation of human remains found buried far beneath the surface of the mountain landscape that figures as an analogue to the investigation of images and—or as—representational surfaces is thus made explicit and literal. The images then cut to shots of the broader landscape of the painting and the “corresponding” or “parallel” image from the video footage. The right-hand image (from 2010) shows the mountainside from the perspective of a city street; instead of the streaming bodies on the painted mountainside, we see passing motor traffic. A billboard is visible in the foreground that displays an advert for the cosmetics brand Yanbal including a woman’s face and the tagline: “carnaval de color” (“carnival of colour”). In the background, the mountainside looms behind the billboard: face is grounded by landscape in a kind of montage within the single frame of the right-hand image, which is in turn juxtaposed with Berrío’s landscape in the left-hand frame.

Figure 6: Eighteenth-century canvas and twenty-first century billboard: two surfaces that demand archaeological scrutiny. Photo: The Silver and the Cross © Harun Farocki, 2010.

It is surely no coincidence that Farocki’s installation closes on this image of face and landscape: the implication of a cosmetic surface in juxtaposition to the contours of the surrounding mountainside. The cosmetically made-up face is reminiscent of the repeated attention given to footage of a model being made up in Farocki’s landmark essay film Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges, 1988).[5] The footage was originally featured in the short film Make Up (1973) and is reprised in Farocki’s ars poetica, Interface (Schnittstelle, 1995), evidence of what Farocki termed his Verbundsystem (“composite system”): an industrial metaphor for his artistic practice, which entailed reusing material shot for other, often commercial purposes. The final shots of the installation also recall the allegorical logic of Farocki’s 1997 film Still Life (Stillleben), which suggests a link between the photography of 1990s advertising campaigns and the paintings of sixteenth and seventeenth century Flemish painters. Moreover, as a by-product of the petrochemical industry, make-up is not only an industrial analogue for Farocki’s own composite production system, it also serves as a metonym for the (raw) materiality of image (re)production and its relation to an extractive economy that penetrates the Earth’s surface. If we recall Farocki’s analogy of the benzene ring to articulate his conception of soft montage/cross influence, form and function coalesce in the metonymic structure and extraction of hydrocarbons. This is not to mention the chemicals industry that features centrally in Images of the World and the Inscription of War alongside the earlier and foundational Inextinguishable Fire (Nicht löschbares Feuer, 1969), and specifically, the IG Farben dye factory and the metalworking industry in the former, which anticipates the analytical focus on silver mining in The Silver and the Cross.

In its glorification of a commodity form, the advertisement presents a highly structured composition—in allegorical terms a totality that stands in contrast to the already past or decayed, the topographical ruin, or bodily remains mentioned by the voiceover. The superficiality of the advertising hoarding—both literally and metaphorically—works to impose a surface that must be excavated and investigated further to uncover the hidden, buried, or silent traces of deeply embedded and intertwined historical and representational processes. This image serves as an additional confirmation of the logic that guides Farocki’s practice in The Silver and the Cross: as a physiognomic gaze is applied to the traits that can be detected on the surface of the painted, filmed, or photographed landscape. The decision to dwell on the surface of the billboard advertising cosmetics in this final shot serves to retrospectively refer to the questions of landscapified complexion, blotches, and pigmentation in Berrío’s painting to which Farocki’s video investigation pays close attention earlier in the installation. Moreover, the suggestion of a cosmetic veneer and the composition of an etiolated ideal of beauty (the billboard ostensibly shows a white woman’s face) also have clear colourist implications. The juxtaposition of the billboard with the painted surface further implies a sense that the blots and blemishes of racial and environmental violence on the mountainside landscape can be concealed or covered up by a silence deserving of closer scrutiny. The facialised regime that is implied here means that in Berrío’s painting as in the cosmetic advertisement, the labour and bodies of the region’s Black and Indigenous populations—historic and contemporary—are pushed to the margins of visibility and legibility if not eradicated entirely. The “carnaval de color” so redolent of religious procession and ritual thus comes to perform a profane form of the same meretricious rites of Christianisation and colonisation traced by Farocki across Berrío’s painting.

Conclusion

And yet, as we have observed in the recto/verso logic of Farocki’s picture puzzles placed in the context of Andean understandings of history, it is possible to discern another side to this historical representation and read against the grain of superficial appearance. Doing so affords a mode of redress that unsettles the “asymmetry” of The Potosí Principle exhibition and inheres in the ambiguity and volatility of the video installation’s compositional make-up. Whether conceived of as the unresolved tension of a dialectic without synthesis, an approximation of ch’ixi subjectivity, or both, the cross influence and chiasmus of Farocki’s moving image practice in The Silver and the Cross activates a chain of metonymic association that encompasses analogues of labour and value that are far from stable or fixed. On the contrary, in Farocki’s video installation, representational binaries of surface/depth, inside/outside, margin/centre, invisibility/appearance, simultaneity/succession are troubled by the practitioner’s double perspective.

Perhaps it is a generous or provocative reading to suggest such an affinity between the ch’ixi subjectivity of Indigenous experience and the cross influence of Farocki’s aesthetic practice. And yet, what emerges from Farocki’s many crossings between various kinds of image (re)production is an impulse to enlist the medium of the video camera to perform a forensic examination of superficial representation. This entails not only a meticulous scrutiny of the surface, but also the technique of cross influence, which situates images in a dynamic relationship with each other across space and time, to animate both the embedded and intertwined media genealogies and histories of colonial violence on which such representational surfaces may be seen to rest. In this context, an “archaeology of the surface” in Lippit’s terms marks its terrain with an “X” to span the many registers and scales, erasures and significations, that are bound up in an extractivist economy that is itself also analogous to the representational regimes and material bases of moving image production. Farocki thus implores the viewer of his works to cast a critical eye over cosmetic renderings across a range of media—from the billboard to the painted canvas—in search of who or what is left out of view and unheard.

In this context, it is surely necessary to read Farocki’s intermedial cross influence as media-archaeological practice in all its performativity: “X” marks the spot by self-consciously indexing the intervention of the filmmaker. And yet, this sign of the cross intersects with the multiple crossings between video channels made by the viewer of the installation. As with so many of Farocki’s authorial gestures, there is an inherent, even an instrumental ambivalence that functions to point both to itself and something else at the same time. This “X” directs his viewer toward or into the frame while working from without or outside it to inscribe the epidermal, facialised surface of the painted landscape while also inviting the viewer to consider what depths may be behind or beneath it.

Notes

[1] While the installation’s voiceover repeatedly describes the forensic process of excavating remains, a mass grave of four hundred workers was unearthed by archaeologists in 2014 (“Colonial-Era Mass Grave”).

[2] Alter notes: “When the Spanish decimated the population, they replenished the labor pool with people from West Africa and later with Chinese people who also perished in large numbers due to the hazardous work conditions” (108–09).

[3] Notable examples of these essay films of the 1990s and 2000s include Prison Images (Gefängnisbilder, 2000) and Workers Leaving the Factory (Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik, 1995).

[4] This corporeal model also recalls the foundational history written about the colonisation of the continent and the mythology of Potosí in the Latin American imagination in Eduardo Galeano’s canonical Las venas abiertas de América Latina (Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent).

[5] Alter has also noted how the use of Cynthia Beatt’s voiceover in The Silver and the Cross “forges a sound bridge to her delivery of the commentary in Images of the World and the Inscription of War, an earlier film about the recto/verso of in/visibility” (109).

References

1. Acosta, Alberto. “Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two Sides of the Same Curse.” Beyond Development: Alternate Visions from Latin America, edited by Miriam Lang and Dunia Mokrani, Transnational Institute and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2013, pp. 61–86.

2. Alberro, Alexander. “Ch’ixi Epistemology and The Potosí Principle in the 21st Century.” ARTMargins, vol. 12, no. 2, June 2023, pp. 18–30, https://doi.org/10.1162/artm_a_00347. Accessed 23 July 2025.

3. Alter, Nora M. Harun Farocki: Forms of Intelligence. Columbia UP, 2024.

4. Angus, Siobhan. Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography. Duke UP, 2024.

5. Arboleda, Martín. Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism. Verso, 2020.

6. Berrío, Gaspar Miguel de. Cerro Rico and the Imperial City of Potosí. 1758, oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz.

7. “‘Colonial-Era Mass Grave’ Found in Potosi, Bolivia.” BBC News, 27 July 2014, www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-28508389. Accessed 20 May 2025.

8. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated and with a foreword by Brian Massumi, U of Minnesota P, 1987.

9. Ehmann, Antje, and Harun Farocki. Labour in a Single Shot [Eine Einstellung zur Arbeit]. Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 26 Feb.–6 Apr. 2015.

10. Eshun, Kodwo. “Capitalism, Colonialism & Silver Harun Farocki, The Silver & the Cross 17 Mins.’ YouTube, Uploaded by The School of Advanced Study, University of London, 8 Mar. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKarirIo8tc. Accessed 23 July 2025.

11. Elsaesser, Thomas, and Alexander Alberro. “Farocki: A Frame for the No Longer Visible: Thomas Elsaesser in Conversation with Alexander Alberro.” e-Flux Journal, no. 59, Nov. 2014, www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61111/farocki-a-frame-for-the-no-longer-visible-thomas-elsaesser-in-conversation-with-alexander-alberro. Accessed 1 July 2022.12. Farocki, Harun, “Cross Influence/Soft Montage.” Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, edited by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun, Koenig Books/Raven Row, 2009, pp. 69–74.

13. ——, director. Images of the World and the Inscription of War [Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges].Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin-West, 1988.

14. ——, director. Inextinguishable Fire [Nicht löschbares Feuer].Harun Farocki, Berlin-West für WDR, Cologne, 1969.

15. ——, director. Interface [Schnittstelle]. Musée Moderne d’art de Villeneuve d’Ascq, Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin, 1995.

16. ——, director. Make Up. Larabel Film Harun Farocki, Berlin-West, für BR, München, 1973.

17. ——, director. Prison Images [Gefängnisbilder]. Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin, Movimento Paris, Christian Baute, commissioned by ZDF/3sat, 2000.

18. ——. The Silver and the Cross [Das Silber und das Kreuz], video installation (double projection), Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin, 2010.

19. ——. Still Life [Stillleben]. Video installation for two monitors, Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin, Movimento Production, 1997.

20. ——, director. Workers Leaving the Factory [Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik]. Harun Farocki Filmproduktion, Berlin, WDR, Köln, 1995.

21. ——. Workers Leaving the Factory in Eleven Decades [Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik in elf Jahrzehnten]. Video installation for 12 monitors, produced for the exhibition Kino wie noch nie, curated by Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki, Generali Foundation, 2006.

22. Galeano, Eduardo. Las venas abiertas de América Latina. Siglo XXI Editores, 2004.

23. Haus der Kulturen der Welt. “The Potosí Principle.” HKW, 7 Oct. 2010–2 Jan. 2011, archiv.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2010/potosi/potosi_prinzip_start.php. Accessed 31 July 2025.

24. Jacobson, Brian R. The Cinema of Extractions: Film Materials and Their Forms. Columbia UP, 2025.

25. Jaikumar, Priya, and Lee Grieveson. “Introduction to Media and Extraction: On the Extractive Film.” Media+Environment, vol. 6, no. 1, Nov. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1525/001c.123925.

26. ——. “Media and Extraction: A Brief Research Manifesto.” Journal of Environmental Media, vol. 3, no. 2, Mar. 2023, pp. 197–206, https://doi.org/10.1386/jem_00085_1.

27. Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Atomic Light (Shadow Optics). U of Minnesota P, 2005.

28. Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Duke UP, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822371779.29. Pantenburg, Volker. Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory. Amsterdam UP, 2015.

30. The Potosí Principle: How Can We Sing the Song of the Lord in an Alien Land? Exhibition Guide. Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2010.

31. The Potosí Principle: How Shall We Sing the Lord’s Song in a Strange Land? Exhibition, curated by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, Max Jorge Hinderer, Alice Creischer, and Andreas Siekmann; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, May–Sept. 2010; Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 7 Oct. 2010–2 Jan. 2011; Museo Nacional de Arte and Museo de Etnografía y Folklore, La Paz, 22 Feb.–30 May 2011.

32. Quijano, Anibal, and Michael Ennis. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South, vol. 1 no. 3, 2000, pp. 533–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005.

33. Raengo, Alessandra. On the Sleeve of the Visual: Race as Face Value. Dartmouth College Press, 2013.

34. Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. “The Potosí Principle: Another View of Totality”, The Hemispheric Institute, vol. 11, no. 1, 2014, hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-11-1-decolonial-gesture/11-1-essays/the-potosi-principle-another-view-of-totality.html.

35. Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia, and El Colectivo, editors. Principio Potosí Reverso. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2010. Yumpu, www.yumpu.com/es/document/read/14446444/el-principio-potosi-reverso-ii-encuentro-internacional-de-. Accessed 27 July 2025.

36. Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. Ed. Andrew Skinner, Penguin Classics, 2003.

37. Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U of Minnesota P, 2018.

Suggested Citation

Alexander, Lawrence. ““X” Marks the What? “Cross Influence”, Extractivism, and the Labours of Moving Image Excavation in Harun Farocki’s The Silver and the Cross (2010).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 183–201. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.10

Lawrence Alexander holds a PhD in Film and Screen Studies from the University of Cambridge and is a Leverhulme Early-Career Research Fellow at the Ruskin School of Art (University of Oxford). His writing on topics ranging from BoJack Horseman to Wozzeck has appeared or is forthcoming in publications such as Alphaville, Frames Cinema Journal, and Screen Bodies. He serves on the Editorial Board of German Screen Studies and alongside Molly Harrabin is Co-Editor of the Weimar Film Network.