Displacing the Gaze: Imaging Brazil in Transnational Experimental Cinema and Video Art

Fábio Andrade

[PDF]

Abstract

The encounter between Latin American subjects and landscapes with filmmakers from the global North has been studied primarily through analyses of documentary and fiction films, whether it is through the presence of auteurs like Orson Welles, Sergei Eisenstein, or Luis Buñuel in key moments of the formation of filmic identity in countries such as Brazil and Mexico; their use as backdrop in Hollywood or European films; or the different iterations of Jean Rouch’s documentary workshops Ateliers Varan in the region. The theoretical corpus surrounding the ethics of asymmetrical representation proves insufficient when dealing with another perennial form of audiovisual transnational encounters in Latin America: experimental cinema and video art. This article looks at a group of works made in the past three decades by female artists from the global North who have turned to Brazil as a physical, cultural, and symbolic space that invites destabilisations of conventional filmmaking strategies: Um Campo de Aviação (An Aviation Field, Joana Pimenta, 2016); Teatro Amazonas (Sharon Lockhart, 1999); Inferno (Yael Bartana, 2013), Plages (Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, 2001); and Æqualia (Emilija Škarnulytė, 2023).

Article

In the landmark 1970 essay “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematic Apparatus”, Jean-Louis Baudry asks a provocative rhetorical question which his own essay will try to answer: “Does the technical nature of optical instruments, directly attached to scientific practice, serve to conceal not only their use in ideological products but also the ideological effects which they may provoke themselves?” (40). For his investigation of how the cinematic apparatus—from the camera to the exhibition space—is tied with complex ideological processes, from macropolitical relations to microscopic mechanisms of individuation, Baudry’s essay became influential enough to generate an entire subfield of cinema studies, now known as apparatus theory. However, its incorporation within aesthetic analyses is hardly widespread, and is yet to fully infiltrate more dominant frameworks, such as narratology, national cinemas, or genre studies.

This lethargy becomes more pernicious when dealing with sociopolitical contexts historically dispossessed by those very same ideological processes that the cinematic apparatus both concealed and projected—in the case of this essay, Latin America. The persistent ideological reinvisibilisation within film scholarship doubles down on this dispossession as if business as usual. But, more importantly, it refuses to consider that the encounter between the cinematic apparatus and these spaces and people takes place within peculiar circumstances that are also at work in the films themselves, and that are being reimagined and renegotiated in their form. This essay investigates how Latin America is both recognised and embraced in multiple ways by several non–Latin American experimental filmmakers and video artists as a perceptual and cognitive disruption capable of destabilising the presumptions concealed by the cinematic apparatus, and its role in forging Western individuation.

Before the Cinema, A Horizon Line

In 2004, the Brazilian philosopher Paulo Arantes gave a public talk on the global state post-9/11 titled “O Mundo-Fronteira”—the frontier-world—proposing a genealogy of the mechanisms of otherness created by the Western world dating back to the invention of the Lines of Amity in 1559. A juridical agreement between the Spanish and the Portuguese that set a precedent for all of Europe, the Lines were drawn roughly west of the Canary Islands and south of the Tropic of Cancer to prevent conflicts between European territorial states beyond the line from resulting in war on European soil. Extractive capitalism and the self-image of modern Europe were consolidated in unbalanced mutuality: for European states to acknowledge each other’s sovereignty in a system of international law, they “created” this other space that could never be recognised as sovereign, and where total exploitation could go on unchallenged. The “New World” thus served as an escape valve for the impulses of a once “barbarian” regime that needed to be preserved elsewhere to sustain a new civilizational model in the “Old World”.[1] For that to happen, that space beyond the line should never be recognised as an equal—a perennial parallax that continuously frames, actually or metaphorically, Latin America as a “land of cannibals”.[2]

This juridical and cartographical slicing of the world following a series of lines is imbricated with simultaneous processes related to perception and subjecthood. As noted by Hito Steyerl, “the use of the horizon to calculate position gave seafarers a sense of orientation, thus also enabling colonialism and the spread of a capitalist global market, but also became an important tool for the construction of the optical paradigms that came to define modernity, the most important paradigm being that of so-called linear perspective.” This other line presupposes a single viewer (in fact, a single eye) who is, in turn, gifted with the impression that the whole world is organised for their gaze.

This self-centered visual economy has had manifold consequences in cinema. As Robert Stam and Louise Spence observe, “the same Renaissance humanism which gave birth to the code of perspective—subsequently incorporated, as Baudry points out, into the camera itself—[…] produces us as subjects, transforming us into armchair conquistadores” (4). In a study of depictions of Brazil in US and European cinemas, Tunico Amancio highlights how a previous form of popular entertainment already created a shared imaginary around real places and historical events: the panorama (13–17). Comprising a single platform in the centre of a rotunda-like construction covered with paintings carefully installed to hide any seam that could break the illusion of total immersion,

the panorama played its part as a “privileged indicator” (as TV does today) representing cities, heroic actions and landscapes, building and transmitting a collective imaginary tailored by painters and entrepreneurs in search of clients […] It is then that individual imagination and singular fantasies get replaced or contaminated by a collective imaginary composed of clichés and stereotypes. (Amancio 15; my trans.)

The repercussions of this foundational problem in cinema have been primarily detected in documentary and fiction films, using variations of the anthropological concepts of emic and etic.[3] Coined by linguistic anthropologist Kenneth Pike, these two terms find more concise definitions in the words of James Lett: “Emic constructs are accounts, descriptions, and analyses expressed in terms of the conceptual schemes and categories that are regarded as meaningful and appropriate by the members of the culture under study,” while “etic constructs […] are regarded as meaningful and appropriate by the community of scientific observers” (382–83). A manifestation of the emic as cultural validation applied to film analysis can be found in Lúcia Murat’s Olhar Estrangeiro (Foreign Gaze, 2006), a documentary feature inspired by Amancio’s book featuring actors, directors, writers, and producers—chiefly American, French, and British—of films that either took place in or referenced Brazil as a space “beyond the line”. Works such as Blame It on Rio (Stanley Donen, 1984), L’Homme de Rio (That Man from Rio, Philippe de Broca, 1964), and Lambada—The Forbidden Dance (Greydon Clark, 1990) are eviscerated for mischaracterising the country through geographical or juridical errors, and upholding stereotypes. But Murat also frames the commitment to authenticity as a burden. When discussing with director Zalman King about Wild Orchid (1989), his mash-up of Rio de Janeiro and Bahia—two states that are roughly as far apart as London and Budapest—Murat argues that she could never have a similar “poetic liberty” with New York City, because everybody knows that, for instance, there is no jungle there. Stephanie Dennison takes this scene to conclude that “it is thus the lack of knowledge to start with, or perhaps lack of historical interest in looking beyond clichés, of places such as Rio de Janeiro or Brazil more broadly, that make such creative license problematic” (154).

But what if this familiarity is, in fact, depriving New York City of a radical alterity that can re-imagine it? Whether it is in the Hollywood western or the European art film, narrative cinema has been dominated by the realist illusion established by linear perspective, disseminated by panoramas, and maintained by the continuity-editing system.[4] The notion that films can “misrepresent” presupposes the stability of a representational contract whose very principle is normative, cornering any reactions to this mimetic effect/defect to fall back on a currency that has been just as harmful to the expression and imagination of those “beyond the line”: the burden of authenticity. But, even more so, it introjects the impression that, since they are not an equal, whoever is beyond the line does not have a gaze, and therefore cannot look back.

Before the Horizon, Cinema

In a panorama or in a Hollywood film, linear perspective is also a trompe l’oeil—an impenetrable surface disguised as another imaginary line—and this mirage has also been claimed as a privileged destabiliser by artists working in production modes devoted to investigating the gaze: experimental cinema and its sprawling presence in the museum world. Filmmakers like Maya Deren, Bruce Conner, and Chick Strand, for instance, have created landmark works of experimental cinema in tension with the spaces and faces of Haiti and Mexico. Instead of holding on to representational clichés or following the hanging carrot of authenticity via research practices that are hardly any less contentious, the films discussed in this article look at Latin America—more specifically, Brazil—as a place that challenges the position held by both the filmmaker and the filmic apparatus.

These dynamics find a powerful analogy in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s definition of Amazonian perspectivism as “capable of providing a counter-description of the image drawn of it by Western anthropology and thereby capable, again, of ‘returning to us an image in which we are unrecognizable to ourselves’” (55). Instead of working to make the outsider’s gaze less problematic, these works use different strategies—often contrasting the centrality of the camera with the enveloping nature of sound—to submit their own positionality to this other perspective that reimagines and reimages both cinema and the asymmetries at its core. Using different filmmaking strategies, Um Campo de Aviação, Teatro Amazonas, Inferno, Plages, and Æqualia problematise their presence to create different forms to be together.

The Troubled Horizon

“Brasília is constructed on the line of the horizon” (Lispector). These words open “Visão do Esplendor” (“Vision of Splendor”), a short story by the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector—herself a Ukrainian immigrant with a degree in Law.[5] A work of creative nonfiction, “Vision of Splendor” positions the 1960-inaugurated capital of Brazil designed by Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa as both a modernist utopia and a glitch in linear perspective. “Wherever people stand,” she goes on, “children might fall, and off the face of the world. Brasília lies at the edge” (Lispector).

The opening words of “Vision of Splendor” are the first ones heard in Um Campo de Aviação, a 14-minute-long short film by the Portuguese filmmaker Joana Pimenta, produced by Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab. The quotation nonetheless comes not at the beginning but only eleven and a half minutes into the film. Read by the filmmaker with a recognisable Portuguese accent that adds another layer of foreignness to Clarice Lispector’s own—a woman who spoke and wrote with a lisp—the sentence hovers over a black screen, retroactively introducing verbal clarity to an otherworldly collection of images and nonverbal sounds.[6]

Shot in Brasília and Fogo, an island in Cape Verde close to where the Lines of Amity were drawn, Um Campo de Aviação explores liminal spaces between the concrete and the abstract. The two real locations are emphasised in their uncanniness, turning the Cape Verde island into a science fiction setting, and Brasília—a larger-than-life, science fiction city—into a miniature model. As manifestations of and against Portuguese colonisation, both places are connected by a directorial choice that rejects the very principle of the grandes navegações: the horizon line. Even though the film title promises amplitude, Um Campo de Aviação opens with a series of panoramic movements shot on 16mm that fail to find any vanishing point behind trees and walls silhouetted by nightfall. The same movement is repeated in different locations—a mountain range in Cape Verde; a widescreen window near Oscar Niemeyer’s Pombal monument at Praça dos Três Poderes, in Brasília—again denying a vanishing point. In their radical alterity, the locations repel the penetration of the ethnographic gaze, turning mountains into layers of film grain, and clouds into veils that block the view.

Figure 1: A panoramic movement without horizon in Um Campo de Aviação (Joana Pimienta).

Terratreme Filmes/Film Study Center/Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), 2016. Screenshot.

The fragmented appropriation of Lispector’s “Vision of Splendor” concludes this experiential estrangement as both text and subtext. While Pimenta’s several panoramic movements and evocative landscape shots seem tied to the single eye of the camera, this centrality is eroded by the uncanny placelessness of the acousmatic narration, which remains “fluctuating, constantly subject to challenge by what we might see” (Chion 22). Instead of a “voice of God”, which connotes “a position of absolute mastery and knowledge outside the spatial and temporal boundaries of the social world the film depicts” (Wolfe 256), the acousmatic voice in Um Campo de Aviação is graced with a frail precision by the director’s accent, which is promptly dispersed by borrowing someone else’s words. This hollowed-out specificity is significant. In stories such as “O Búfalo” (“The Buffalo”, 1960), “O Ovo e a Galinha”(“The Egg and the Chicken”, 1964), “Tentação”(“Temptation”, 1964), and “As Águas do Mundo” (“The Waters of the World”, 1971), Lispector created encounters with the natural world—an animal; a stretch of landscape—that bounced the gaze back, reflecting humans’ ambivalence between exteriority (as a sovereign vantage point for whom the world is organised) and interiority (as part of the organic whole that stands before them). In “The Waters of the World”, this otherness is in fact embodied by the horizon line itself:

There it is, the sea, the most unintelligible of non-human existences. And here is the woman, standing on the beach, the most unintelligible of living beings. As a human being she once posed a question about herself, becoming the most unintelligible of living beings. She and the sea.

Their mysteries could only meet if one surrendered to the other: the surrender of two unknowable worlds made with the trust by which two understandings would surrender to each other.She looks at the sea, that’s what she can do. It is only cut off for her by the line of the horizon, that is, by her human incapacity to see the Earth’s curvature. (Lispector)

Instead of an organising principle, the horizon is reframed as a bias, a byproduct of the human apparatus’s deficiency in accurately making visual sense of the world. Challenging sovereignty, the encounter with the sea and all it has come to protect, allow, and represent in colonial relations accentuates this handicap, disentangling the desire to look from the illusion of knowing.

Pimenta’s use of Lispector’s prose manifests the untranslatability of the encounter between the Portuguese gaze and the familiar foreignness of the Lusophone Atlantic—an encounter that has both concrete and imaginary repercussions. “[Brasília] used to be inhabited by extremely tall blond men and women who sparkled under the sun”, the narration continues, abridging different parts (for some have fallen off the face of the world) of Lispector’s invented history for that made-up place. “They were all blind,” she completes, adding meaning to the black screen paired with the film’s final and only voice-over narration. But the text also addresses the internalisation of asymmetries by that very city that it reimagines while it contemplates: “[Brasília] was built with no place for rats. A whole part of us, the worst, precisely the one horrified by rats, that part has no place in Brasília.”

“Constructed on the line of the horizon” of Brazil’s own expansion toward the west, to borrow Lispector’s words, the construction of the new capital also resulted in the eviction and marginalisation of the workers who built it to the satellite cities that surround it. This is a central concern in Pimenta’s later films with the Brazilian director Adirley Queirós as either cinematographer or codirector, shot in Ceilândia and Sol Nascente: Era Uma Vez Brasília (Once There Was Brasília, 2017) and Mato Seco em Chamas (Dry Ground Burning, 2022). In the modernist dream in concrete of Costa and Niemeyer, “a whole part of us, the worst” (Lispector)—precisely the one that must be constantly investigated—has no place: these white paper buildings recycle colonial practices that taint the country like an original sin.

In Um Campo de Aviação, the filmic utterance renounces stability by enacting this “no place” (Lispector) in the dissociation between image, voice, and text, diachronically separating these elements so that any synthesis of meaning can only come through difference, and any possibility of centralisation must necessarily be built from its surroundings. As Michel Chion has defined, “the acousmêtre is everywhere, its voice comes from an immaterial and non-localized body, and it seems that no obstacle can stop it” (24). While the film’s point of view is stretched between Portugal, Fogo, and Brasília—three precise locations that converge in the platform of the film’s unfeasible panorama—it is actually Pimenta’s voice speaking through Lispector’s words that turns these landscapes into a possibility of flight.

The Reversed Proscenium

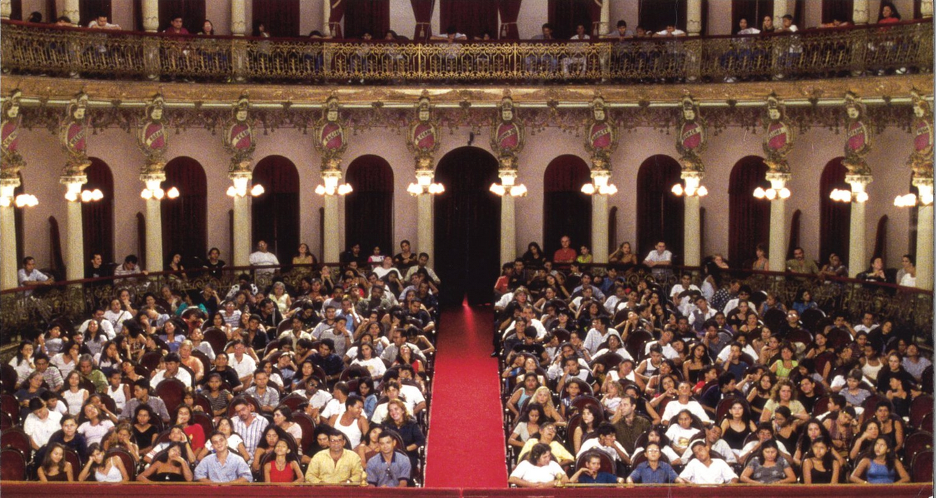

The destabilisation of point of view by sound takes radically different forms in Sharon Lockhart’s Teatro Amazonas. Made for theatrical exhibition, the 39-minute-long 35mm film comprises a single, 29-minute-long shot in the location that renders its title: a nineteenth-century theatre in Manaus, the capital of the state of Amazonas, in Northern Brazil.[7] This take is recorded from the vantage point of the stage, in a symmetrical tableauthat splits the image both vertically, centring the corridor between the left and right sections of the audience, and horizontally, giving equal prominence to the venue’s decor, on the upper half, and the spectators filling all the visible seats on the bottom half.

Figure 2: Teatro Amazonas in the eponymous film. Teatro Amazonas. Sharon Lockhart, 1999. Screenshot.

The soundtrack consists mostly of a (seemingly) live performance of an original piece by Becky Allen, in which the voices of Coral do Amazonas extend overlapping vowels—a prominent phoneme in Brazilian Portuguese—to create a continuous sound. On the surface, that is all. But, as is often the case with structural films, the joy of the experience lies precisely in unpacking the seemingly flat.

Ivone Margulies describes Teatro Amazonas, the venue, as a patchwork of colonial architecture. Built between 1884 and 1896, just before the arrival of the cinematograph in Brazil, the seven-hundred-seat theatre designed by architects Jorge Santos and Felipe Monteiro, with décor by Henrique Mazzaloni and Crispim do Amaral, was meant to be “constructed almost entirely of materials imported from Europe […] but as soon as it became difficult to import goods, local artists started making elaborate fakeries. Cement and plaster columns, wainscoting, eyed windows, and balustrades were created to look as if they were made of marble and other noble materials” (Margulies 99). Named after the state where Brazil’s rainforest is mostly located, the theatre is a Third World pastiche of the European presence in the local colonial imaginary. This ethnographic component is multiplied by nondiegetic information: in her research process, Lockhart recorded interviews and made still portraits when casting every single person in the “audience”. According to the end credits, the cast was clustered according to their neighbourhood and proportionally distributed to mirror each region’s demographic presence in the city. This extradiegetic information unfurls another meaning for the title: in the film, Amazonas, the state, is itself a theatre that has been assembled, rehearsed, and directed to create an anthropological spectacle.

However, the film incorporates ethnography with a vengeance. Countering the stratification of space used as criteria for the research and casting processes, the continuous wide group shot ends up calling attention to the singularities in each person’s behaviour over the collective. Small differences get amplified: a woman dozes off in her chair, another whispers something to the spectator sitting next to them, a boy stands up and paces around, a man rests his head on his hand—an exhausted proletarian or Auguste Rodin’s Le Penseur? While the credits and the ancillary information provide context, this redirection of attention that turns the audience into a spectacle is also a result of diegetic elements. Using droning voices that oscillate in pitch and tone, Becky Allen’s minimalist piece recalls the tuning of an orchestra before a concert starts. Are we and the audience all waiting for something to begin? The director’s decision to keep the house lights on for the entirety of the shot (and film) corroborates that what is being shown is not so much a spectacle, but the moments that precede it.

The protraction of this preliminary moment infuses the gaze with anticipation for something else to start… but it does not. Teatro Amazonas reduces the system of mimetic representation sustained by ethnography, narrative, and linear perspective to its minimal elements. Disentangling it from storytelling, the film displaces William Archer’s landmark definition of drama as “expectation mingled with uncertainty” (227)—in this case, in the very structure of the piece, playing with the viewer’s uncertainty about what, when, and where the action is actually taking place. As noted by Timothy Martin, in Lockhart’s Brazilian project “photographic and filmic moments drift between poles of apparent articulation, concealment, and deferral with respect to their subject(s), to the degree that the viewer must at times doubt whether the apparent subject is indeed the subject intended” (13). In Teatro Amazonas, “the audience is there to be watched, and we are there to watch them being watched, audience to audience” (13).

As an uninterrupted record of continuous time, the soundtrack creates the impression that image and sound are synchronous and that the choir is just visually inaccessible—either in the orchestra pit, below, or just behind the camera. But, as the musical piece progresses, it gradually fades toward the background, as coughs, giggles, whispers, and the rustle of clothes against the fabric of the seats dominate the last ten minutes of the soundscape. At first, this rebalancing directs the viewer’s attention from the inaccessible stage to the audience, displacing theatricality, and switching from medium to site specificity. But what if these sounds are coming from behind the camera? Teatro Amazonas may indeed be about what has been happening on stage from the very beginning: the presence of the camera. After all, the conventions of linear perspective are also behind a revolution in theatre: the development of the Renaissance stage, whose core configuration is still dominant in stage design. While this transformation of the scenic space stabilised the vantage point of the spectator, it paradoxically multiplied the possibilities of leakage between the stage and the audience. As noted by Fabio Finotti, in medieval and Roman Theatre “the real theatrical space was in front of the public and wasn’t visibly opened behind the backdrop that worked as a sort of boundary of the area consecrated to the play” (26). However, that paradigm would soon change. As he explains:

In sixteenth-century Italian theater, the world that the perspective opens in front of the spectators is connected to the same one that they have left behind them […]. The scene becomes the center for interplay between reality and fiction that fuses the space occupied by the spectators with that of the actors. The horizontal structure of theatrical stage, cloistered by the scenery, intersects the vertical articulation of the perspective lines, leading the spectators beyond the backdrop toward a part of their real world. (27–28)

It is precisely this porousness between who watches and who is being watched that is activated, scrambled, and dramatised in Teatro Amazonas, playacting the back-and-forth between attraction and repulsion that is involved in looking and being looked at. Is Sharon Lockhart looking at Teatro Amazonas, or is the theatre that she has assembled looking at her? In that pastiche of European theatre, cinema ends up becoming the subject matter of its own ethnography.

Eye in the Sky

The point of view generated by linear perspective is not ahistorical. As Walter Mignolo notes in an essay about the construction of subjectivites and maps, the “growing European awareness of a previously unknown part of the earth”—in this case, the Americas—“became a decisive factor in the process of integrating the unknown to the known, which also transformed the configuration of the known” (264). Joined at the hip with colonial exploitation, the horizon line is also bound to be transformed by significant changes in both visual economy and geopolitical conceptions of space. For Arantes, the world defined by the Amity Lines has been replaced by a new world order best defined in the words of Zygmunt Bauman: “The global space has assumed the character of a frontier-land. […] In a frontier-land, alliances and the frontlines that separate them from the enemy are, like the adversaries, in flux” (90). The linearity of the geographical and cognitive world had been replaced by a different kind of (dis)orientation.

The sovereignty of the vantage point has also been affected by this shift, as emerging technologies and media habits have created new territories for exploration and exploitation, as well as areas of refusal. Take, for instance, the internet. On 10 October 2024, the Brazilian Instagram profiles GreengoDictionary and HistoriaNoPaint posted a joint video that appropriated content whose authorship was not disclosed, shot with a vertical aspect ratio on a lower-resolution camera that has come to be associated with cell phones. Taken from the vantage point of a ship, the shot focused on the imposing waves in a rough, stormy sea that crashed against the hull. The horizon dissolves behind clouds, as the camera struggles to pan around, shaken by the tides. Superimposed, a single piece of text reframes that unidentified piece of footage, collapsing multiple layers of space and time: “pov: vc é um europeu indo atrás de tempero” (sic)—“pov: ur an european searching for spice.” The meme represents its own paradigm shift—a critical joke adrift in a new form of commons that gets profiled, privatised, and monetised into a virtual space. As Steyerl noted in 2011:

Our sense of spatial and temporal orientation has changed dramatically in recent years, prompted by new technologies of surveillance, tracking, and targeting. One of the symptoms of this transformation is the growing importance of aerial views: overviews, Google Map views, satellite views. We are growing increasingly accustomed to what used to be called a God’s-eye view. […] Just as linear perspective established an imaginary stable observer and horizon, so does the perspective from above establish an imaginary floating observer and an imaginary stable ground.

Her choice to describe the extreme verticality of point of view as God’s-eye view, instead of the more commonly used bird’s-eye view, recalls a term that was once in common use in film scholarship in different Romance languages: the zenithal shot. Borrowed from astrophysics and solar geometry, the zenith is both more precise and less specific than the attribution of the gaze to a bird, or even to God. This cold detachment seems to better fit the new frontier-world (Bauman), and the growing presence of this “eye in the sky” addressed by Steyerl—an eye that is often disembodied, mechanical, and desubjectified.

The popularisation of drones has turned aerial footage into another documentary convention. Once saved for extravagant projects, such as Werner Herzog’s 1992 film about the Gulf war, Lektionen in Finsternis (Lessons of Darkness), hovering cameras are now a common part of the mainstream nonfiction toolbox, subsuming the conventional “voice of God” into a divine point of view. However, as with every other convention, this point of view and its dissemination are not neutral, representing yet another overlap (or perhaps joint project) of the surveillance, military, and entertainment industries.

Much like with linear geometry, the asymmetries embedded in this other vantage point also create new possibilities of critique. As Choi-Fitzpatrick notes, aerial images “open spaces for and raise new questions about contestation, meaning making, and resistance. In particular, these tools require fresh theorizing of the verticalization and colonization of the ground, the sky, and the subterranean […] about what space is public and which is private.” As with the predicaments of linear perspective and the separation between audience and stage, experimental filmmakers have also looked at Latin America—this space beyond the line—through this peculiar viewpoint as a relief from the grounded politics of borders and nation-states.

The ambiguity of the materialisation of this other dimension gets semantic precision in Inferno. Shot by the Israeli artist Yael Bartana in São Paulo, the 21-minute-long videovirtualises a real event: the construction of the Templo de Salomão (Temple of Solomon)—a mega-church by the Evangelical neo-Pentecostal transnational denomination Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (Universal Church of the Kingdom of God), built after the mythical temple in Jerusalem. In the film, Bartana creates a multiethnic religious parade of people dressed in white who gather for the inauguration of the temple. Combining elements of Judaism, Afro-Brazilian religions, and Carmen Miranda–inspired fruit headdresses, the crowd enacts Brazil’s myth of racial democracy, evoking the type of “positive image” of diversity one was used to seeing in commercials by brands such as Benetton, and that has since infiltrated independent and mainstream cinema, as well as video art.[8] However, at the end of the video, this pastiche temple (and film) will have the same destination of the original that it has been designed to mimic: its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar, the King of Babylon. In a Hollywood ending, the new temple is engulfed in flames and eventually blown up to pieces. Its ruins will be revered.

While narratively surprising, this fate is announced from the very opening of the film, which instantiates a visual refrain: an aerial shot. Inferno opens with the camera hovering above dense trees, in a typical zenithal shot that has been used in works such as the Netflix true crime series Bandidos na TV (Killer Ratings, Daniel Bogado, 2021) to depict Brazil’s forests. However, as the movement progresses, it gradually tilts up to frame the (lack of) horizon of the cityscape of São Paulo. Hovering in the air, the camera zooms in, and the title Inferno (Hell) is superimposed on the city, turning that disembodied image into both a description of life in a modern metropolis, and a prescient bad omen. The opening shot is followed by another aerial shot that reframes the motif of contrasting worlds: instead of the trees, São Paulo’s skyscrapers now appear surrounded by the unfinished houses of the local favelas. This prologue employs the “eye in the sky” in its usual ambiguity. While the view from above allows for the “objective” measuring and description of geological characteristics, its omnivision has a strange metaphysical quality that reconnects “heaven” and “sky”—which, in Portuguese as in other Romance languages, are subsumed into a single word: “céu”.

However, such an ambiguity is enacted just in order to be revoked: Inferno’s third shot is another aerial take, but this time the shadow of the helicopter is projected over the cityscape. This shadow creates a peculiar form of grounding. In The Good Drone, Choi-Fitzpatrick examines a different device used for aerial image-making to create a more nuanced catalogue of the implications of this vantage point: the balloon. Connected to the ground by a rope or thread, the balloon suggests a distinct visual economy from the one traditionally associated with the view from above:

Here we have the technological antithesis to Donna Haraway’s oft-cited gaze from nowhere. The view from nowhere is “tied to militarism, capitalism, colonialism, and male supremacy.” The view from nowhere tries to “distance the knowing subject from everybody and everything in the interests of unfettered power.” The view from nowhere eschews accountability. An aerial view from somewhere, on the other hand, exudes accountability. The view from somewhere links the curious explorer to engaged publics by means of a simple thread. (Choi-Fitzpatrick).

In Inferno,the shadow of the helicopter has a similar effect to that of the balloon’s thread, locating and implicating the filmmaking gaze as part of the view it creates—like Pimenta’s panoramic movements, and Lockhart’s self-aware tableau. But the helicopter—which quickly becomes three—is not only the vessel of the film’s physical vantage point. They are also flying, into the Temple of Solomon, the Ark of the Covenant, a menorah, and other religious relics. These props serve a double purpose. On the one hand, they problematise the complicated relationship between the Evangelical imaginary and Judaism into a born-again Judeo-Christian mythology. But on the other hand, they signal the director’s own ethnic, cultural, and social positions in that imaginary world, emphasising the “from-somewhereness” of all that is shown.

Figure 3: The shadow of the helicopter over São Paulo. Inferno. Yael Bartana, 2013. Screenshot.

Inferno doubles down on this fundamental defamiliarisation of the culturally specific in the film’s second half, which concerns the destruction of the Temple of Solomon. As noted by Bartana herself, “I shot and edited with stylistic references to Hollywood action epics, so that the final film employed a new term ‘historical pre-enactment,’ a methodology that commingles fact and fiction, prophesy and history.” By both embracing and rejecting the theological connotations of the God’s-eye view as part of Hollywood’s apparatus, the film presents this apocalyptic vision of Brazil as a view from an implicated somewhere, unveiling what the apparatus is designed to imply.A similar thread grounds Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s Plages, a 35mm short film produced by Le Fresnoy. Shot from the window of the twenty-first floor of a hotel on Avenida Atlântica, in Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro, the 15-minute-long film documents the interaction between the neighbourhood’s landmark sidewalk panels by Roberto Burle-Marx and the gathering crowd that awaits the seaside fireworks show on New Year’s Eve. Instead of showing the horizon line subliminally suggested by the beach, the film shoots Copacabana from above, flattening the people against the rippling waves, and pinning the camera’s exploratory panoramic movement against the asphalt below. This shot, which rolls uninterrupted for more than nine minutes, is complemented by a collection of disembodied voices that tell or sing stories in Portuguese. Disembodied, the acousmatic is nonetheless specific, providing, through language, accent, and testimony, a paradoxical “on the ground” perspective of Copacabana.

Figure 4: Copacabana from above. Plages. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, 2001. Screenshot.

This tension between showing and telling, public and personal, communal and individual, seeing and not seeing creates a filmic form that translates the peculiar porousness of life in Brazil. As written by Pablo León de la Barra, in a text addressed to Gonzalez-Foerster, this blurring of boundaries provides relief for the regimented project of Western modernity:

In contrast to the American model of the urban sea front, in which hotels and other buildings are generally constructed directly on the beach, and the beach itself is transformed into private property, in Rio the beach is a democratic space, with a walkway for the pedestrian and a road for the car, an arrangement which creates a space between the buildings and the beach […] Copacabana’s fluidity, like that of many other spaces in Rio, could be a model for a possible social and urban utopia, but this utopia is also a fragile one. (77)

In Plages, this fragile utopia is also expressed by a subtle shift in perspective. While the opening shot’s duration gives it documentary indexicality, evoking the off-screen ticking clock that motivates that collective wait, the film’s first cut is triggered by the beginning of the fireworks show. Skipping the precise moment in which one year becomes another—and, in this case, one millennium—the cut also provokes a gradual change in the regime of images, as the film starts superimposing shots of the fireworks over that informal audience. The collapsing of shot and reverse shot into a single composition materialises Copacabana’s fragile utopia of togetherness, which is both celebrated and challenged by pouring rain. Through the combination of fireworks and raindrops, Plages emphasises the ambivalent nature of the filmmaking gaze that at once documents and projects the vision of Brazil as a “a possible social and urban utopia” for Western modernism, represented by the interaction between the people and Burle-Marx’s sidewalk mural.

While both Inferno and Plages create zenithal shots using techniques and apparatuses (the helicopter and the skyscraper window view) that attach a body to the gaze, an even more enigmatic use of the “eye in the sky” appears in Emilija Škarnulytė’s Æqualia, an immersive video installation co-commissioned by Canal Projects and the 14th Gwangju Biennale. As a dominating focal point in the room when installed at Canal Projects, in New York City, 19 January – 30 March 2024, the video consists primarily of drone shots captured on high-definition video in an extremely wide aspect ratio (approximately 4.3:1—nearly twice as wide as anamorphic cinemascope) of a precise geographic location: the gathering of the waters of Rio Negro and Rio Amazonas, in the Amazon region of Manaus, Brazil. While the image is largely disembodied, appropriating even the lexicon of satellite imagery by providing the precise location (3°8′12″S 59°54′17″W) in the liner notes of its exhibition, the profilmic is, once again, implicated, like the thread that connects the ground to a balloon’s aerial view: at the visual seam between Rio Negro’s characteristically dark waters and Amazonas’s milky beige, the artist herself swims, wearing a mermaid costume, alongside Amazonian pink dolphins—the “boto cor-de-rosa”.

Figure 5: The zenithal shot films the artist as mermaid. Æqualia. Emilija Škarnulytė, 2023. Screenshot.

The suspended authorship of the zenith is directly mirrored by the artist’s diametrical presence, self-exoticised as a half-fish humanoid from elsewhere that interacts with an indigenous species vulnerable to extinction, and which is immersed in a peculiar Amazonian mythology: the river dolphin allegedly can turn into a handsome man who will seduce and impregnate women who live close to the river—a myth explored in Walter Lima Júnior’s Ele, o Boto (The Dolphin, 1987).

The prevalence of interstitial states is made visually striking by the contrasting waters of both rivers, which invite reflections on Brazil’s myth of racial democracy as both a practice and a projected utopia. This predilection is mirrored further in the exhibition space. In its display at Canal Projects, Æqualia was shown in a large screen positioned in front of medium-sized glass structures that were laid down on the floor before it, over a black reflective surface. The film literally poured out of the screen, disarranging its own horizontality with a clear reflection that doubled its presence on the floor, inviting yet another view from above: the eye of the spectator that contemplated the sculptures. The panorama returns, but instead of focusing on what its images represent, it is the very possibility of immersive looking that is thematised.

The trompe l’oeil is, therefore, reclaimed as panorama, but instead of historical events or faraway lands, its surfaces lead the gaze elsewhere. In his text, Pablo Léon de la Barra quotes words by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster that illuminate the radical potential of this experience: “I’ve always looked for a relationship to the environment, an immersion, rather than a relationship to the object [ ... ] a relationship with things that surround us” as a way of “seeing not what’s in front of you, but rather inside of you” (84). Historically, Brazil seems to have been a fertile space for that kind of fold, in which an outward impulse seems to turn inwards, and the separation between who sees and who is seen, what sees and what is seen, is temporarily suspended. In the legendary exploration of the Amazon documented in the imaginative travel journal O Turista Aprendiz (The Apprentice Tourist, posthumously published in 1976), Mário de Andrade expresses that internal multiplicity in a projection of his own interiority over the Amazon river: “Nothing pleases me more than to be by myself and look at the river in the fullness of day, deserted. It’s extraordinary how everything bubbles up with beings, with gods, with indescribable beings behind it all, especially if the yonder in front of me is a bend in the river.” Through the failed ethnographic cartographies of Um Campo de Aviação and Teatro Amazonas, or the seemingly all-seeing zenithal shots in Inferno, Plages, and Æqualia, the spectators as “armchair conquistadores” (Stam and Spencer 4) look at Latin America, but end up seeing something else: a possibility for cinema, and the ideological effects it has always subsumed and promoted, to go on without anything to hide, for reflexivity has been claimed as its only ethical vocation.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Hernani Heffner and Nora M. Alter for suggestions that have helped shaped this article, and Heissell Contreras for assisting me in this research.

Notes

[1] Mark Netzloff argues that the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, which established the Lines of Amity, actually does not make a distinction between European soil and rivalry over the Americas. However, it has nonetheless been cited as precedent for that in subsequent treaties, such as the Franco-Spanish Peace of Vervins (1598) and the Anglo-Spanish Treaty of London (1604), and it has “held a status as established fact” in diplomatic practice (Netzloff 54–68).

[2] In “Caliban: Notes Toward a Discussion of Culture in Our America”, the Cuban writer Roberto Fernández Retamar unpacks the lasting imbalance behind the image of a cannibalistic Latin America through a quintessential work of Western literature: William Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

[3] For a more detailed discussion on the terms “etic” and “emic,” see Harris (568–604).

[4] In separate works, David Bordwell notes how both Hollywood and the European art film are governed by the same principle: realism. “In Hollywood cinema, verisimilitude usually supports compositional motivation by making the chain of causality seem plausible [...]. Classical Hollywood narrative thus often uses realism as an alibi, a supplementary justification for material already motivated causally” (“Classical Hollywood” 19) While this cause-effect chain is challenged by European art cinema, realism remains untouched: “The art cinema motivates its narratives by two principles: realism and authorial expressivity. On the one hand, the art cinema defines itself as a realistic cinema. It will show us real locations (Neorealism, the New Wave) and real problems (contemporary ‘alienation,’ ‘lack of communication,’) […]. Most important, the art cinema uses ‘realistic’—that is, psychologically complex-characters” (“Art Cinema” 57).

[5] For the persistence of the Law in Lispector’s literature, see Pichon-Rivière.

[6] Lispector was born in the Ukraine, and moved to Recife, Brazil, when she was nine years old. Later, she spent fifteen years abroad, living in Europe and the United States between 1944 and 1959.

[7] Lockhart’s Brazilian project also resulted in the publication of an exhibition catalogue with two scholarly essays detailing the research process behind the film, and photographs taken for a different project at fishing villages in the Amazon region (Lochart and Schampers).

[8] For Brazil’s myth of racial democracy, see Freyre.

References

1. Amancio, Tunico. O Brasil Dos Gringos: Imagens No Cinema. Intertexto, 2000.

2. Andrade, Mário de. The Apprentice Tourist: Travels Along the Amazon to Peru, Along the Madeira to Bolivia, and around Marajó before Saying Enough Already. Translated by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux, E-book edition, Penguin Books, 2023.

3. Arantes, Paulo Eduardo. “O Mundo-Fronteira: Conferência no Congresso Balanço do Século XX.” Sentimento da Dialética, 2021, sentimentodadialetica.org/dialetica/catalog/book/104. Accessed 16 Oct. 2024.

4. Archer, William. Play-Making; A Manual of Craftsmanship. Small, Maynard and Company, 1912.

5. Bartana, Yael. “Interview with Artist Yael Bartana” Aesthetica, 26 Aug. 2014. aestheticamagazine.com/interview-artist-yael-bartana.

6. _____, director. Inferno. 2013.

7. Baudry, Jean-Louis. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus.” Translated by Alan Williams, Film Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 2, Winter 1974–1975, pp. 39–47. https://doi.org/10.2307/1211632.

8. Bauman, Zygmunt. Society Under Siege. Polity, 2002.

9. Bogado, Daniel, director. Bandidos na TV [Killer Ratings]. Caravan Media

Quicksilver Media, 2019.

10. Bordwell, David. “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” Film Criticism, vol. 4, no. 1, 1979, pp. 56–64.11. ——. “The Classical Hollywood Style, 1917–60.” The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, edited by David Bordwell, Janet Steiger, and Kristin Thompson, Routledge, 1985, pp. 1–72.

12. Broca, Philippe de, director. L’Homme de Rio [That Man from Rio]. Les Films Ariane/Les Productions Artistes Associés/Dear Film Produzione, 1964.

13. Chion, Michel. The Voice in Cinema. Translated by Claudia Gorbman, Columbia UP, 1999.

14. Choi-Fitzpatrick, Austin. The Good Drone: How Social Movements Democratize Surveillance. E-book edition, MIT Press, 2020.

15. Clark, Greydon, director. Lambada—The Forbidden Dance. Cannon Films/Film and Television Corporation, 1990.

16. Dennison, Stephanie. Remapping Brazilian Film Culture in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2020.

17. Donen, Stanley, director. Blame It on Rio. Sherwood Productions, 1984.

18. Fernández Retamar, Roberto. “Caliban: Notes Toward a Discussion of Culture in Our America.” The Latin American Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Ana Del Sarto, Alicia Ríos, and Abril Trigo, Duke UP, 2004, pp. 83–99.

19. Finotti, Fabio. “Perspective and Stage Design, Fiction and Reality in the Italian Renaissance Theater of the Fifteenth Century.” Renaissance Drama 36/37: Italy in the Drama of Europe, edited by William N. West and Albert Russell Ascoli, Northwestern UP, 2010, pp. 21–42.

20. Freyre, Gilberto. The Master and the Slaves (Casa-Grande & Senzala): A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization. Translated by Samuel Putnam, 2nd ed., U of California P, 1986.

21. Gonzalez-Foerster, Dominique, director. Plages. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, 2001.

22. GreengoDictionary and HistoriaNoPaint. “pov: vc é um europeu indo atrás de tempero.” Instagram, 10 Oct. 2024. www.instagram.com/p/DA8gBhGRn1k/?igsh=bXFwYXJ2eHdmc2ox.

23. Harris, Marvin. The Rise of Anthropological Theory: A History of Theories of Culture. Thomas Y. Cromwell Company, 1971.

24. Herzog, Werner, director. Lektionen in Finsternis [Lessons of Darkness]. Premiere Medien/Canal+, 1992.

25. King, Zalman, director. Wild Orchid. Vision PDG, 1989.

26. León de la Barra, Pablo. “Gardens, Parks, Landscapes, Environments, Exhibitions, Museums, Pavilions, Tropics, Beaches, Swimming Pools, Deserts, Microclimates, Immersions, Heterotopias.” Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster 1887–2058, edited by Emma Lavigne with Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Prestel, 2016, pp. 72–85.27. Lett, James. “Emic/Etic Distinctions.” Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology, edited by David Levinson and Melvin Ember. Henry Holt and Company, 1996, pp. 382–83.

28. Lima Júnior, Walter, director. Ele, o Boto [The Dolphin]. Luiz Carlos Barreto Produções Cinematográficas, 1987.

29. Lispector, Clarice. “The Buffalo.” The Complete Stories.E-book edition, New Directions, 2018.

30. ——. “The Egg and the Chicken.” The Complete Stories.E-book edition, New Directions, 2018.

31. ——. “Temptation.” The Complete Stories.E-book edition, New Directions, 2018.

32. ——. “Vision of Splendor.” The Complete Stories.E-book edition, New Directions, 2018.

33. ——. “The Waters of the World.” The Complete Stories.E-book edition, New Directions, 2018.

34. Lockhart, Sharon, director. Teatro Amazonas. 1999.

35. Lockhart, Sharon, and Karel Schampers. Sharon Lockhart: Teatro Amazonas. Edited by John Alan Farmer, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Kunsthalle Zürich, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, and NAi Publishers, 1999.

36. Margulies, Ivone. “At the Edge of My Seat.” Sharon Lockhart: Teatro Amazonas, pp. 93–109.

37. Martin, Timothy. “Documentary Theater.” Sharon Lockhart: Teatro Amazonas, pp. 9–31.

38. Mignolo, Walter D. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. U of Michigan P, 1995.

39. Murat, Lucia, director. Olhar Estrangeiro [Foreign Gaze]. Limite/Okeanos/Taiga Filmes, 2006.

40. Netzloff, Mark. “Lines of Amity: The Law of Nations in the Americas.” Cultures of Diplomacy and Literary Writing in the Early Modern World, edited by Tracey A. Sowerby and Joanna Craigwood, Oxford UP, 2019, pp. 54–68.

41. Pichon-Rivière, Rocío. “Choreographies of Consent: Clarice Lispector’s Epistemology of Ignorance.” Postmodern Culture, vol. 30, no. 3, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1353/pmc.2020.0019.

42. Pimenta, Joana, director. Um Campo de Aviação [An Aviation Field]. Terratreme Filmes/Film Study Center/Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), 2016.

43. Pimenta, Joana, and Queirós, Adirley, directors. Mato Seco em Chamas [Dry Ground Burning]. Cinco da Norte/Terratreme Filmes, 2022.

44. Queirós, Adirley, director. Era Uma Vez Brasília [Once There Was Brasília]. Cinco da Norte/Terratreme Filmes, 2017.

45. Rodin, Auguste. Le Penseur (The Thinker). 1904, Musée Rodin, Paris.

46. Škarnulytė, Emilija, director. Æqualia. 2023.

47. Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Edited by Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine, Folger Shakespeare Library, Simon & Schuster, 2015.

48. Stam, Robert, and Louise Spence. “Colonialism, Racism, and Representation: An Introduction.” Screen, vol. 24, no. 2, 1983, pp. 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/24.2.2.

49. Steyerl, Hito. “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective.” e-flux, vol. 24, April 2011, http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_8888222.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2025.

50. Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Cannibal Metaphysics. Univocal, 2014.

51. Wolfe, Charles. “Historicizing the Voice of God: The Place of Voice-Over Commentary in Classical Documentary.” The Documentary Film Reader: History, Theory, Criticism, edited by Jonathan Kahana, Oxford UP, 2016,pp. 264–80.

Suggested Citation

Andrade, Fábio. “Displacing the Gaze: Imaging Brazil in Transnational Experimental Cinema and Video Art.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 146–164. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.08

Fábio Andrade is an Assistant Professor of Film at Vassar College, with a PhD in Cinema Studies from New York University, and an MFA in Filmmaking from Columbia University, with a CAPES/Fulbright fellowship. He specializes in Latin American cinema and video art. His work has been published by Film Quarterly, the Criterion Collection, Senses of Cinema, Cinética, DAAD, Film Comment, among others. He is also an artist, with works in sound, music, and video for theatrical projection and gallery exhibition.