Unfinished Thinking and the Unfinished Film: Feminist Filmmaking in Cuba, Catalunya, and Scotland

David Archibald and Núria Araüna Baró

[PDF]

Abstract

This article reflects on a creative research project which utilises audiovisual technologies to foster conversations with feminist activists in four historically related cities— Havana (Cuba) which is twinned with Glasgow (Scotland), and Matanzas (Cuba) which is twinned with Vilanova i la Geltrú (Catalunya). Under the banner “Ragged Cinema”, we are undertaking a project which brings together feminists across the four cities to explore how no-budget, collaborative filmmaking might be utilised to encourage experience sharing between activists in the Global South and the Global North, and develop translocal networks of support and solidarity. By developing a crosscultural project rooted in specific patriarchal states, capitalist and communist, we aim to amplify the often-unheard voices of nonstate actors. In December 2023, a step towards this occurred when work-in-process films made by the activists were presented at the Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano de La Habana (International Festival of New Latin American Cinema of Havana) alongside a festival symposium organised with our Cuban partners under the heading “Cine dialógico” (“Dialogical Cinema”). This article combines images from an unfinished academic film and an experimental written text, and seeks to illustrate the merits, or otherwise, of analysing academic work in a state of incompleteness.

Article

In this article, we reflect on and through an ongoing research project which utilises audiovisual technologies to foster conversations between feminist activists in four cities which are linked through local authority twinning arrangements: Havana (Cuba) which is twinned with Glasgow (Scotland), and Matanzas (Cuba) which is twinned with Vilanova i la Geltrú (Catalunya). We are currently undertaking a British Academy-funded project involving participants from the four cities to explore how no-budget, collaborative filmmaking might be utilised to build translocal networks of support and solidarity amongst feminist activists and collectives.[1] In developing a crosscultural project rooted in three specific patriarchal nation-states, with economic models labelled respectively as capitalist and communist, our aim is to explore how alternative networks and platforms might be utilised to amplify the voices of non-state actors which are often unheard within dominant media landscapes, moving beyond the abstract nature of nations, reaching towards sites of everyday experience, and, in the process, towards fostering a radical empathy (Givens). In doing so, we aim to make manifest what Catalan feminist Marina Garcés has termed “un món comú” (“a common world”), one in which we imagine the links between every irreducible subject without collapsing their differences or conflicts, fully cognisant of the conflicting nature of a decolonising practice. During the Covid19 lockdown, we worked together remotely to create Comrades together-apart (Camarades-junts-i-a-banda, Araüna Baró and Archibald, 2021), a short film featuring mobile phone footage of feminist activities in our respective areas—Scotland and Catalunya—and edited it online together. Inspired by feminist physicist Karen Barad’s notion of “cutting together-apart”, we utilised a dialogical filmmaking methodology to explore how activists might use low-budget digital technology to work together-apart at distance. We then pondered whether that which had been forced on us—that is, working together at distance—might in fact be utilised by political activists as a way to foster creative conversations and build alliances and solidarity. Following filmmaker and theoretician Ursula Biemann, we consider film as a device that enables the creation of translocal geographical connections with specific sites and experiences, revealing the “unfinished side of citizenship” and of lives (79). Or to align it with Barad’s work on diffraction, the entanglements and responsibilities between places, times, and human and nonhuman subjects.

A pilot project commenced in autumn 2022 when we assembled four groups of activists, one in each of the cities. We are based in Glasgow and Vilanova i la Geltrú, respectively, and we drew on existing connections to develop groups in these two cities. In Glasgow, under the aegis of Glasgow Havana Film Festival (HGFF), we distributed an open call for feminist activists to participate in the project. In Catalunya, we drew on previously established relationships with feminist collectives in Vilanova i la Geltrú, namely, Bullanga Feminista (Feminist Bullanga Association), l’Esquerda (Assembly for Sexual and Gender Dissidence in Vilanova i la Geltrú), and l’Ateneu Vilanoví (Cultural Association).[2] In Cuba, we worked with HGFF to establish suitable partners and formed an effective and ongoing relationship with Karibuni, a community centre in Havana Vieja led by Kenia Serrano Puig (University of Havana). Through this initial connection, we have been introduced to scores of community groups and activists in both Cuban cities, including Cuba in Africa, Matanzas Deaf Association, Matanzas Journalists Union, Afrofeminist Articulation, TransCuba, La Marina neighbourhood association, and many others, whose participants have been active in the project.

Figure 1: Damarys Benavides Criollo and Silvia Véliz Olivares talking after a Cine Dialógico meeting, Karibuni Community Centre, Havana, March 2025.

From the rushes of the project’s unfinished and untitled film.

The assembled groups had mixed skill sets. For instance, the Glasgow group included several members with extensive experience in filmmaking, whereas the Catalan group had wide experience of feminist activism but less experience working with film. In Cuba, groups are even more diverse, with participants representing the abovementioned collectives, but also journalists and television workers, philosophers, and film students. We secured basic AV equipment for all four groups: DSLR cameras, tripods, microphones, and more. Over the next year or so, the activists began the process of meeting, discussing, and developing short films which connected the four cities in different ways.[3] In December 2023, four work-in-process films made by the activists were presented at the Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano de La Habana (International Festival of New Latin American Cinema of Havana) alongside a festival symposium organised with our Cuban partners under the heading “Cine dialógico” (“Dialogical Cinema”), that took place on 14 December in the Hotel Nacional de Cuba.[4] The films were Pegadas a mi alma (Stuck to My Soul, Maydi Bayona Estrada, 2023) from the Havana group; Acariciar la vida (Caressing Life, Grupo de Cine Dialógico Glahamavilla de Matanzas, 2023); Pel·lícula de les mans (The Hands’ Film, Beth Johnston, Emma Flynn, Úna O’Sullivan, 2023) from the Glasgow group and featuring footage from both the Glasgow and Vilanova i la Geltrú groups; and Pasos a una mirada trans (Steps Towards a Trans View, Damarys Benavides, 2023) from the Havana and Matanzas groups. Other screenings in cinemas and activist and domestic settings have taken place in Matanzas, Glasgow, and Vilanova i la Geltrú, and some films are still being made within the framework of the project.

The final outcome related to the British Academy grant is a low budget (circa £20,000) academic film on this research, which we plan to complete before the conclusion of the project, and which will be inspired by Helena Lumbreras and Colectivo de Clase’s aim of filming “the dreams of people fighting to change their lives” (qtd. in Borrull 1), by Cuban director García Espinosa’s concept of “imperfect cinema” and his defence of a popular art fused with life, and by Solanas and Getino’s conceptualisation of filmmaking as a generator of theory. In the act of making the film and throughout the project, we are addressing the three imbricated research questions, which we outlined in the grant application:

Can a film production methodology informed by theories related to deep listening, diffraction, and the dialogical be utilised by academics from the Global North working with non-academic partners in the Global North and the Global South to develop a more inclusive and participatory creative practice?

Can low-budget AV technology, channelled through dialogical communication, be utilised by feminist activists to develop translocal forms of filmmaking to effectively amplify feminist political discourse, complexify Western conceptions of feminism, and contribute to more just political and economic transitions across capitalist and communist, colonial, and ex-colonial, nation states?

How might creative research methods help to positively disorder the ecology of epistemologies in the Global South and the Global North?

We are still working with and through these questions, and this article combines rushes from the film with an experimental text in which we reflect on this work.

Henk Borgdorff suggests that artistic research is distinct from academic research in that the former advances “unfinished thinking” (44), and Alix Beeston and Stefan Solomon flag the feminist possibilities of analysing unfinished films. In creating this article, we sought to explore the merits, or otherwise, of theorising academic work in a state of incompleteness, before the final cut has delimited possibilities. The reader will have no problem identifying gaps and omissions in our article, and in our argument: we know that we have more reading and thinking to do. Our aim is that the article functions as a provocation to thought. We are aware that it might not achieve this aim: we are not afraid of failure. We are grateful to the detailed comments provided by the peer reviewers and the editors who have faced the challenging task of responding to an article in such form. Their input has been invaluable in helping us to advance our thinking.

Figure 2: Spontaneous sound recordist, Leodán Fleitas Aballi, tests mics with interviewees Marian Franklin Fuentes and Doryana Fuentes Cancino, Matanzas, March 2025. Project film rushes.

Methodologies

In answering the project’s research questions, we developed the idea of a dialogical cinema which draws on “deep listening”, a practice we encountered first through an awareness of the work of composer Pauline Oliveros, which she states is “intended to heighten and expand consciousness of sound in as many dimensions of awareness and attentional dynamics as is humanly possible” (xxiii). This concept has been brought into academic work by scholars such as Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Ben Silverstein when working with Indigenous and Global South communities, and by political activists who regard “listening as a form of activism” (O’Brien). As scholars based in Europe, we recognise that individuals and communities in the Global South have historically utilised methodologies and discourses beyond the “north-euro-androcentric paradigms” with universalising pretensions (Rodríguez and Da Costa) that have informed our academic background.

Our approach towards deep listening also builds on Jean-Luc Nancy’s distinction between hearing and listening in that the latter involves, as he puts it, “straining towards a possible meaning, and one that is not immediately accessible” (7). Deep listening for us is not simply durational. It is not listening for longer; rather, it involves critically reflecting on the positionality of ourselves as researchers, implicated as we are in postcolonial power imbalances. We are also long-standing activists in the feminist and labour movements, and our academic work is entangled in discourses and deeds of international solidarity related to these movements. Deep listening, then, is essential for the emergence of even the possibility of solidarity. As this article responds to a call for papers that deals with foreign practitioners—mostly Western—working in and about Latin America, we are highlighting our relationship with the project’s Cuban participants.[5] Considering that our project involves people and organisations from each of the four cities, we are aware that we are engaging with “multiple others”, thereby problematising simplistic binaries. Deep listening requires that we work from a position of deep humility across all four cities; however, when working in Cuba, we are particularly aware of the negative impact of previous colonial interventions, and of the extractivist potentiality of our own interventions.

Figure 3: View of Matanzas River from an apartment in the city. March 2025. Project film rushes.

Our filmmaking methodology is also influenced by Mikhail Bakhtin’s thinking on the dialogical and Karen Barad’s thinking on diffraction. Whereas Bakhtin’s work stresses the importance of the dialogical as an open-ended, continuous movement in which meaning is always-already contextually determined in an ongoing chain of dialogues, Barad’s work on diffraction involves the study of objects or subjects through analysis of how they intra-act rather than inter-act. This approach continually collapses the self–other, subject–object binaries, postulating that single entities can be comprehended only through actions with the other, and it is these actions which reveal their qualities in any specific moment. By bringing deep listening, diffraction, and the dialogical together, we understand the ongoing dialogues of the participants through their intra-actions rather than as isolated individuals or communities. Our methodology, moreover, is not interdisciplinary but intradisciplinary, one that refuses disciplinary boundaries, including Film Studies, Anthropology, and Gender Studies. We then attempt to read texts in, through, and across these disciplines. In reflecting on our methodology, we continually explore the extent to which hegemonic and reified binaries and borders—disciplinary, geographical, and conceptual—can be disrupted through artistic and academic knowledge production. This is crucial in theorising a research practice which refuses the practice–theory and artistic–academic research binaries. This is our abstract position: utilising this process as a laboratory, we are in the process of testing it out. While developing this project in Cuba, we have learned of other approaches to filmmaking akin to these endeavours, which have been put into practice before our own work started, as noted by filmmaker Gloria Rolando at the 2023 Havana festival post-screening discussions. “Dialogical cinema” or “cine dialógico”, then, has become a shared and fluid label used to encompass a multimodal film and conversational practice which allows us to set a decentred frame for working together. We started using the label “dialogical cinema” as a machine for thinking; with Cuba, “cine dialógico” has been and is many other things, some of which we are still working to understand.

Unfinished Thinking and an Ecology of Epistemologies

Arts and Humanities academics working in Global North institutions are tasked with creating new knowledge about the world, and that knowledge tends to be clearly articulated in written form. There can be nuance, of course; however, one might expect an essay or monograph to arrive at a singular position, which can be expressed unambiguously in words. Even in what is variously described as “practice-research”, “artistic research”, “creative research” and so on, academics are required to produce written statements that make explicit the findings of their research. What might be gained, or lost, if it were done another way? Borgdorff suggests that “it is not formal knowledge that is the subject matter of artistic research, but thinking in, through and with art” (44). We are unconvinced by Borgdorff’s binary between artistic and academic research; however, if academic outputs are artworks, rather than artworks being the subject of academic scrutiny, what might we expect of them? Why should we demand that these artworks articulate clear and coherent arguments? Might we not hope for something more expansive, alive, and open to broader possibilities? Academic film critics often lean towards art cinema, which David Bordwell notes is characterised by ambiguity (156). What would artistic academic outputs look, sound, and feel like if they embraced ambiguity rather than demanded (or even performed) certainty? We are interested in how the process of “unfinished” artistic and academic activity—that is, work which refuses narrative closure, which consciously leaves a gap or an entry point for the audience to walk through—might be viewed not as a lack, but as a strength.

In the seminal Screen debate on realism and film form, Colin McCabe argued that the “classic realist text” was unable to contain contradiction and advanced the notion of a revolutionary cinema in content and form. Leaving the debate’s merits to one side, what required greater attention was a recognition of the formal qualities of the participants’ essays, which were more aligned with the features of the classic realist text than the radical form of cinema which was being demanded. While academic film criticism largely champions experimental and ambiguous cinema, most academic film criticism conforms to, and is locked within, the established critical orthodoxy, presenting research findings in written narrative form, and with a clear argument supposedly free of contradiction. There is, though, a performativity in the seemingly nonperformative; that is, the academic essay performs closure because these are the conventions and requirements of the genre. What would scholarship in the Global North gain if it embraced more fully forms of knowledge production that it had previously been involved in erasing? In grappling with the ontology of epistemology, we note that C. L. R. James’ seminal history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins, was developed initially as a theatrical performance in 1936. Might artistic research be utilised to establish affective, emotional, and other ways of knowing beyond the dominant knowledge regimes promoted by the West? Where can we find spaces where the binary between art and intellectual work is less demarcated? How (and with whom) can we develop these spaces, always cognisant that creative forms were also central to colonial rule, not least, cinema itself?

Figure 4: A taxi driver refuels a taxi with petrol purchased from a passing driver on the road from Matanzas to Havana, March 2025. Project film rushes.

In our work, we seek to explore how academic outputs in the Global North might be reimagined; to accommodate, indeed, embrace, and foster methods of knowledge production which it was previously complicit in erasing. In doing so, we aim at developing a more positive ecology of epistemologies across the Global Norths and Souths. Articulated, authoritative knowledge has been one of the tools used for the reproduction of power, and Curiel notes that, as the institutions in charge of producing legitimised (traditionally Western) discourse, universities are the centre of the coloniality of knowledge (Curiel and Guerrero). How, then, might we operate when we are working both inside and outside the Western academy and contribute to anticolonial methodologies? How might we refuse to ignore the double standards by which decolonising projects are funded whilst universities in the Global North operate in a colonialist mindset, a process made explicit in university league tables and the exploitative fees that are demanded of the selected international students who can afford them? How might we hope to create work that fosters change yet refuses the “Scramble for Impact”? How might we make knowledge accountable to the power dynamics it sustains and by which it is sustained and produced? And how should we perform as bearers of the institutional knowledge of our funding bodies and our own institutions? These are only some of the questions which have emerged during this work. Our own thinking here is unfinished: perhaps, though, a deep listening ethics is a starting point for a recalibration of epistemologies. Working together creatively, we hope this might help tie these elements together; this requires an emotional predisposition to work, the same generosity that any transformative action needs.

Writing Is a Practice

Writing is a practice. Essay writing is a practice. Monograph writing is a practice. Yet, the status of writing as practice is largely invisible. Although there has been an increase in alternative forms of academic knowledge creation in recent years, writing remains the dominant form of scholarship in the arts and humanities. In conventional and, we might add, conservative thinking writing is positioned as superior to practice. Indeed, the fact that creative and artistic practice forms of research are named as such, whereas standard written outputs are categorised easily as “research”, highlights this unspoken hierarchy. This position exemplifies Maurice Blanchot’s observation that academic research “refuses to question the form that it borrows from tradition” (3). The primacy of the word in Western culture is well established: we wonder whether the prioritisation of theory created in the written word over theory created in, through, and with practice is also gendered with the latter cast as “women’s work” by some scholars who, consciously or otherwise, prioritise the word on the page. In disturbing the theory–practice binary, greater consideration must be given to the affordances which might emerge from developing theoretical insights in multifarious form. Concomitant with this, more thinking needs to be done about the limitations of the existing dominant forms.

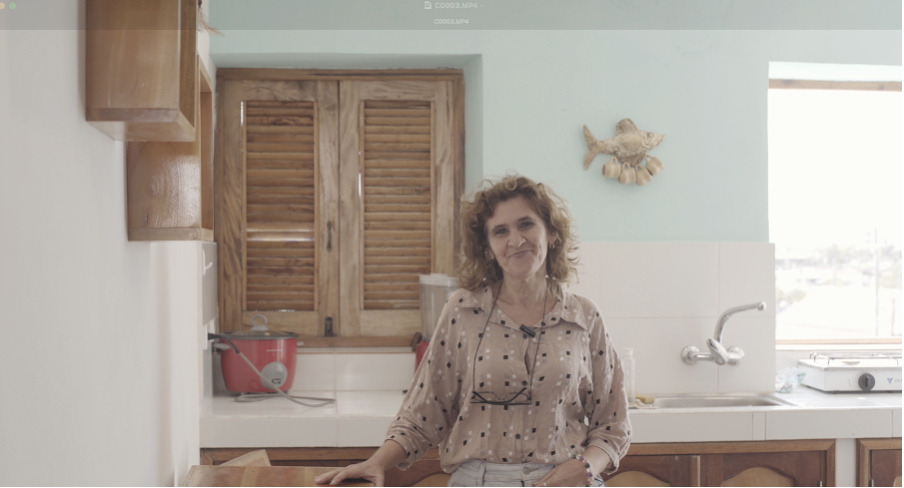

Figure 5: Damarys Benavides Criollo being interviewed, Havana, March 2025. Project film rushes.

Silence and Scholasticide

The first time it was reported that our friends were being butchered there was a cry of horror. Then a hundred were butchered. But when a thousand were butchered and there was no end to the butchery, a blanket of silence spread. (Brecht 247)

Remaining silent on one of the worst atrocities against women and children in our lifetime is indefensible. When 70% of those killed are women and children; when Palestinian women are digging through rubble to find their missing children; when mothers are holding their lifeless babies; when families are burning to death in refugee camps while they sleep; when mothers watch their children die from hunger as a result of Israel’s starvation campaign; and when children cry for food amidst famine conditions, silence is not a matter of being “politically correct”—it is a betrayal of feminist principles (Aldossari).

Figure 6: Demonstration in Vilanova i la Geltrú against gender-based violence, 25 November 2024.

Co-organised by Catalan participants Ana Ballesteros García, Sonia Roig Fornells and

Anna Stanton Solabre. Project film rushes.

Solidarity Outwith Identity

December 2022: during the workshops in Cuba, women in Havana and Matanzas record a short video message to Victor, a young Catalan man facing three years of prison for his part in disrupting the far right on the streets of Barcelona. In this process, solidarity emerges as an embodied, physical, and intellectual experience: it emerges in struggle. The word “outwith”, used primarily but not exclusively in Scotland, which means “beyond” or “outside”, might be useful in highlighting the tension between difference and the universal. If solidarity fosters a commonality of experience, a sense of unity in action, how might it negotiate difference? This question has provoked significant thinking in feminist scholarship, and the phrase “solidarity beyond identity” has been utilised previously (as related to the contemporary circulation of images, by Hito Steyerl). However, does this suggest that the solidarity which emerges does so “beyond” or with the dissolution of identity? Playing with words and the slippages of meaning in different local contexts is a methodology to deal with doubts and ideas. “Outwith”, which conjoins “out” and “with”, suggests they operate “together-apart” (Barad), crossfertilising, diffracting, constituting, and reconstituting its parts in political struggles which recognise differences within the universal, but which moves forward with an emphasis on commonality such that the universal becomes a mobilising unattainable rather than an actually existing physical reality (perhaps discourses around commonality are more useful than those around universality). In moving from an intradialogical encounter between the women from the four cities to an open and public call of solidarity from Cuban women to a young Catalan man engaged in radical political activity outwith conventional feminist politics, this dialogical encounter makes manifest the possibilities of common engagement between different subjects.

Dialogical

The video message to Victor was received enthusiastically in Vilanova i la Geltrú and shared on antirepressive collectives’ social media throughout Catalunya. This remote yet close connection provoked a sense of surprise and warmth; a sense that even with words having different meanings in both contexts (“solidaridad”, “antifascista”, “repression”), translations could bring about new ways of supporting each other’s human rights. For us, it was an early example of how the audiovisual process of production might foster productive and positive translocal dialogues, which were in line with our own dialogical approach to filmmaking, which we developed when we made our first short film.

Figure 7: Doryana Fuentes Cancino being interviewed in Matanzas, March 2025. Project film rushes.

Yet if our first reference to the dialogical was Bakhtin, as detailed above, we have become more aware of dialogical approaches to creation and filmmaking (even if they are not always named as such) in the Global South and among feminist and radical collectives and thinkers elsewhere. When we describe a certain cinema as “dialogical”, we navigate the contradiction that, from a dialogical standpoint, actually “all cinema is dialogical” or, more precisely, may be observed as such. However, for us, a conscious “dialogical” cinema would be one which makes explicit this nature and incorporates dialogical potentialities into its way of working in all aspects of production and exhibition.

So, how might we conceptualise a “dialogical cinema”, or one which can use the dialogical properties of audiovisual media, to foster solidarities in what Marina Garcés defines as a “common world”? Pierrette Malcuzynsky reads Bakhtin in feminist terms, asserting that in dialogical texts there is an encounter between “multiple consciousness, coming from diverse horizons [that] converge to constitute a specific conjuncture” (33). These conjunctures do not require the closeness of agreements (another connection of the dialogical with the unfinished), but only a coexistence and interrelation which may adopt many forms, and coresponsibilities. Conjunctures and conjectures about others are also part of this interrupted yet ongoing communication, and an intrinsic part of what the dialogical provokes: expectations about us, others, and encounters, imaginations of better, fairer worlds, yet imaginations that may not entirely converge. Richard Sennet attempts to clarify the difference between the dialogical and the dialectical, suggesting that the former does not need to reach a common agreement nor a superior state of knowledge—as a dialectical process would imply when contradictions clash and new syntheses emerge. In the dialogical conversation, “though no shared agreements may be reached, through the process of exchange people may become more aware of their own views and expand their understanding of one another” (Sennet 19). To Sennet, the dialogical overcomes the pressure to homogenise, tame or negate difference and thus its subversiveness remains intact, challenging universalism (20). Working from a feminist decolonial perspective, Francesca Gargallo argues for the convenience of this critical distance attainable by the dialogical to appreciate togetherness in difference. Then it becomes clear that there is an order built around the non-uttered idea that “only the Western is Universal”, and this order is sustained in a system of knowledge that confines “habits, intelligences, cosmovisions and diverse forms of communication to a specific local and folkloric field, not expected to be reproduced in the next generations” (Gargallo 62; our trans.). Consequently, differences, if tolerated, were considered the minority survival of a past that is deemed to disappear, or one that remains as a museum curiosity.

Figure 8: From left to right, Beth Johnston, Amparo Fortuny, Nuria Araüna Baró and David Archibald, Glasgow, December 2024. Project film rushes.

In our work, we are aware that a dialogical relationship does not come merely by sharing space, technology, or even a creative process. Following Gargallo, we recognise that there needs to be a specific emotional predisposition for this dialogue to take place. For Gargallo, a dialogue needs a subject prepared to open oneself to the “grammatical, symbolic and spiritual universe” of another person, and such openness requires the absence of mutual fear (58; our trans.). Fear is an emotion strongly linked to processes of coloniality and inequality more generally, as a culturally constructed category that has come to be employed to legitimise human exploitation. The Cuban city of Matanzas translates literally as “the killings”, named as such after the execution of Spanish colonialists by the indigenous population in the sixteenth century. The name “Matanzas” served as a reminder of the fear of the “savage resistance” that must be contained through the various mechanisms set in motion by the colonial entities, and a legitimation story for the violence already exerted by the colonial settlers and armies. Simultaneously, the fears of the indigenous population were promoted by the colonial powers to subdue any form of resistance and benefit from local resources and human exploitation. Against this historical backdrop, how can a contemporary dialogue take place? We wonder if the internationally well-known (very popular in Catalunya and elsewhere) left-wing saying “que la por canviï de bàndol” (“for the fear may switch sides”), by assertively calling for an analysis of individual positionality, can open possibilities.

Feminisms

Ochy Curiel points out that market logics are absorbing academic critical theories, which constitute an elitist space. In this context, even “alterity, that which is considered different, subaltern, is also potable for the market and continues to be raw material for Western Colonialism” (100).

We expect to get dirty.

We expect that we will make many mistakes.

We are not afraid of making mistakes.

She who makes no mistakes makes nothing.Feminism is the long fight for gender equality, and yet a term that has acquired many different meanings in diverse contexts. It has also been instrumentalised to legitimise the colonial predations in the contemporary world. For bell hooks, we need to overcome an image of feminism which relates women’s equality with imperialism (78), and which has imposed onto non-white, non-European or poor women normative views regarding what should be their fight—sometimes at the expense of exterminating their peoples, exemplified by Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

We can only grasp what feminism may be if we understand its multilocality, the various instances where it is remade, every day, within and outwith the university. We aim, then, at contributing to what Márgara Millán has named as a “feminism from above and from the left” (11). Millán also defines a “decolonising epistemology, whose objective is feminist knowledge itself”, postulating that this knowledge “is being made in multiple places and through many voices” (11). We are aware of the potential pitfalls of totalising narratives; however, we aspire to what we have termed “alliancial thinking” on feminist and decolonising epistemologies, and creative forms of knowledge production.

Interrupting (hegemonic) feminisms implies creating distance from certain sources and lines of thought and practice, allowing ourselves to be interrupted. Interruptions are linked to the dialogical, where the discourse is not one but a multiplicity. In these flows, Mariana Alvarado has also highlighted the importance of listening to create knowledge that differs from what is possible within the colonial matrix. For Alvarado, listening is a theoretical practice built by active subjects, one which allows other kinds of knowledges (and feminisms) to be articulated around what she calls “the listening of life-stories, testimonies and experience narratives” (56).

Figure 9: Silvia Véliz Olivares being interviewed, Havana, March 2025. Project film rushes.

Very concretely, audiovisual technologies can be used to listen and set in motion encounters, as well as amplify voices that are marginalised both in corporate media outlets and in institutional media regulation. Alvarado suggests that there needs to be a “restitution of the space of enunciation and of the times of audibility” for voices that, emerging from subalternity, can “(dis)organise in, from, for the South in every audible interruption, restoring a History from below” (53). Through making films together-apart, not only those who make them (the participants in the project, in Matanzas, Havana, Vilanova, Glasgow, and ourselves) offer our voices, but also seek out others whose voices will be listened to (in the filmmaking process, the film itself, and its exhibition). For us, listening opens a gate to develop further the above-mentioned “alliancial thinking”, a prerequisite for building material alliances.

Technologies and Utopias

In Scorched Earth, Jonathan Crary counterposes the importance of real-life encounters to foster solidarity in activist circles against possible networks of solidarity which might be built through the Internet. Crary makes irrevocable points against online connectivity, mediated through extractivist companies that seek massive data mining and the commerce of our time of life, and highlights the importance of face-to-face encounters. To build a common world, however, requires finding ways to connect with those in remote locations, making visible the entanglements that cross our existences, and using this visibility to dismantle, sabotage, and hack these exploitation networks. We hold on to the Utopian perspective that digital technologies hold out possibilities. This implies an optimistic approach to digital technologies, recognising the possibilities they offer for exposing injustices, facilitating connectivity, and sharing images and sounds related to experiences of time and place. In this sense, we have worked through Hito Steyerl’s concept of the poor image, one that is not concerned about its low resolution, since it has its value in its multiple possibilities for circulating, translating experiences and thus distributing epistemic richness.

Today, it may be difficult to discern what a poor image is, when low-range mobile phones can shoot in high resolution and 4K. In a way, cheap high-resolution images challenge certain stereotypes about who can produce poor or rich images, forcing us to rethink what we mean by poor (again, inequalities must be rendered visible, so they become vulnerable to our attacks). Inequalities amongst images and sounds prevail, and poorness emerges in the languages that one can or cannot learn to express ideas through audiovisual means, the access to certain means of production, the power imbalances inscribed in production processes, the blockade of some products, and the marginalisation of certain kinds of practices and authors. Of course, in Cuba, this has also involved working with fragile yet expensive Internet connections that struggle to send and receive video files, and the very practical implications of the US blockade, which prevents the use of some software that we might have utilised. For example, when we started using project laptops in Cuba, the editing software detected our location, and the applications were immediately blocked. This technological blockage, though, forces the project participants to find alternatives and learn from the many strategies used by Cuban people to deal with the blockade, including the use of VPNs and alternative or unlicensed software.

Filmmaking is also about futures. We take the view that it has the capacity, following Donna Haraway, to support consciousness, imaginative understandings of the world and, also, of the possible (yet to come): speculative fabulation. Making films with feminists is about imagining a Utopia, a word which has etymologically been read as a “good place” and as a “no place”, depending on the reading of the classical Greek prefix “eu-” or “ou-”. There is a tension between the possibility of this good world to come and its permanent nonexistence, contained simultaneously in utopian thought and the well-known motto popularised by Gramsci—but attributed by him to Romain Roland—“Pessimismo dell’intelligenza, ottimismo della volontà” (“Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Yet films may make possible what is still “non” and “good”, or at least this is one of the project’s aims.

Figure 10: Cine Dialógico workshop, Havana, March, 2025. Project film rushes.

In Matanzas, the participants conjured the translocal entity of “Glahamavila”, made up of the initial letters of each of the participant cities. Glahamavila would be a dialogical space, a film festival that would bring together activists and films from the four cities, and an invitation to imagine together what film can do. Glahamavila, a nonexisting yet existing entity, opens a space for utopian and translocal imaginings. An alternative form of being together, either virtually or physically. A small step, in dark times, towards a common world.

Conclusion

What does it mean to conclude,

as bombs drop

and blockades choke?

Notes

[1] The British Academy grant runs from May 2023 to April 2025. A 2022 pilot project was funded by the Glasgow Centre for International Development (University of Glasgow). The article deals primarily with the research conducted until summer 2024.

[2] Havana Glasgow Film Festival was established in 2015 by Glasgow-based writer and filmmaker, Eirene Houston (“About Us”).

[3] The terminology of “zero-budget” filmmaking is problematic in that the labour involved in production is not recognised in any balance sheet. We include the term here to highlight that, beyond the basic filmmaking equipment which we provided to the groups, the films were only possible as a result of the activists’ non-quantified voluntary labour.

[4] The symposium was hosted jointly with Cine Dialógico (the name given to the project by our Cuban partners) and Proyecto Palomas, a community organisation led by Cuban filmmaker and activist, Lizette Vila. For a Spanish-language media report, see Sierra Liriano.

[5] See Araüna Baró and Archibald (“Métodos”) for a Spanish language article on this work.

References

1. “About Us.” Havana Glasgow Film Festival (HGFF), hgfilmfest.com/about. Accessed 14 June 2025.

2. Acariciar la vida/Caressing Life. Directed by Grupo de Cine Dialógico Glahamavila de Matanzas, Matanzas Group, 2023.

3. Aldossari, Maryam. “#MeToo Unless It’s Palestine: Why Western Feminists Ignore Proven Israeli Rape of Palestinians.” The New Arab, 14 Aug. 2024, www.newarab.com/opinion/why-western-feminists-ignore-proven-israeli-rape-palestinians.

4. Alvarado, Mariana. “Epistemologías feministas en los sures comunitarios e indígenas.” Nomadías, no. 31, 2022, pp. 47–73, enfoqueseducacionales.uchile.cl/index.php/NO/article/view/69431.

5. Araüna Baró, Núria, and David Archibald. “Métodos creativos para un feminismo dialógico. Tejiendo alianzas translocales a partir del audiovisual.” Hacia la igualdad de géneros: Comunicación para el empoderamiento, edited by Inmaculada Postigo Gómez and Malely Linares Sánchez, Editorial UOC, 2024.

6. ——. “Ragged Cinema: Twelve Theses on the Making of Comrades Together-apart / Camarades junts-i-a-banda (Araüna Baró and Archibald, Catalonia/Scotland, 2021)”. Framework, vol. 63, no. 1–2, 2022, pp. 13–24, https://doi.org/10.1353/frm.2022.a875873.

7. Archibald, David, and Núria Araüna Baró. “Feminism and Film: A Dialogue.” The Drouth,2021, www.thedrouth.org/feminism-and-film-a-dialogue-by-nuria-arauna-baro-and-david-archibald. Accessed 26 May 2025.

8. Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays.1940. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, U of Texas P, 1981.

9. Barad, Karen. “Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart.” Parallax, vol. 20, no. 3, 2014, pp. 168–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623.

10. Beeston, Alix, and Stefan Solomon. Incomplete: The Feminist Possibilities of the Unfinished Film. U of California P, 2023.11. Biemann, Ursula. Geography and the Politics of Mobility. Generali Foundation, 2003.

12. Blanchot, Maurice. The Infinite Conversation. 1969. Translated by Susan Hanson, U of Minnesota P, 1993.

13. Bordwell, David. “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” Film Criticism, vol. 4, no. 1, 1979, pp. 56–64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44018650.

14. Borgdorff, Henk. “The Production of Knowledge in Artistic Research.” Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson,Routledge, 2011, pp. 44–63.

15. Borrull, Mariona. “Helena Lumbreras, la activista del ‘cine marginal’ que dignificó a la clase obrera en la transición.” El Español, 18 Dec. 2023, https://www.elespanol.com/el-cultural/cine/20231218/helena-lumbreras-activista-cine-marginal-dignifico-clase-obrera-transicion/817668289_0.html.

16. Brecht, Bertolt. “When Evil-doing Comes like Falling Rain.” Bertolt Brecht: Poems 1913–1956, edited by John Willett and Ralph Manheim, Routledge, 1997, p. 247.

17. Comrades together-apart (Camarades-junts-i-a-banda). Directed by Araüna Baró and Archibald, Catalonia/Scotland, 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3hVuar9Uqo.

18. Crary, Jonathan. Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World. Verso, 2022.

19. Curiel, Ochy. “La crítica poscolonial desde las prácticas políticas del feminismo antirracista, colonialidad y biopolítica en América Latina.” Revista Nómadas, vol. 26, 2007, pp. 92–101, nomadas.ucentral.edu.co/index.php/component/content/article?id=298.

20. Curiel, Ochy, and Julián Guerrero. “Por un feminismo decolonial, antirracista y popular: una charla con Ochy Curiel.” Cartel urbano, 9 Mar. 2019, cartelurbano.com/libreydiverso/por-un-feminismo-decolonial-antirracista-y-popular-una-charla-con-ochy-curiel.

21. García Espinosa, Julio. “Por un cine imperfecto.” 1968. La doble moral del cine, Editorial Voluntad, 1995, pp. 11–30. Published in English as “For an Imperfect Cinema.” Translated by Julianne Burton, Jump Cut, no. 20, 1979, pp. 24–26.

22. Garcés, Marina. Un món comú. Tigre de paper, 2022.

23. Gargallo, Francesca. Ideas feministas latinoamericanas. Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México–UACM, 2006.

24. Givens, Terri E. Radical Empathy: Finding a Path to Bridging Racial Divides. Bristol UP, 2021.

25. Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing, U of Michigan P, 1990.

26. Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Experimental Futures). Duke UP, 2016.

27. hooks, bell. Passionate Politics. Pluto Press, 2000.

28. James, C. L. R. The Black Jacobins. 1938. 2nd ed., Vintage Books, 1989.

29. Malcuzynski, Marie Pierrette. “Yo no es un O/otro.” Acta Poética, vol. 27, no. 1, 2006, pp. 19–44, https://doi.org/10.19130/iifl.ap.2006.1.188.

30. McCabe, Colin, “Realism and the Cinema: Notes on some Brechtian Theses.” Screen, vol. 15, no. 2, 1974, pp. 7–27, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/15.2.7.

31. McGrath, Ann, Laura Rademaker, and Ben Silverstein. “Deep History and Deep Listening: Indigenous Knowledges and the Narration of Deep Pasts.” Rethinking History, vol. 25, no. 3, 202, pp. 307–26, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2021.1966201.

32. Millán, Márgara. “Más allá del feminismo, a manera de presentación.” Más allá del feminismo. Caminos para andar, edited by Márgara Millán, Red de Feminismos Decoloniales, 2014, pp. 9–14.

33. Nancy, Jean-Luc. Listening. Translated by Charlotte Mandell, Fordham UP, 2007.

34. O’Brien, Kerry. “Listening as Activism: The ‘Sonic Meditations’ of Pauline Oliveros.” The New Yorker, 9 Dec. 2016. www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/listening-as-activism-the-sonic-meditations-of-pauline-oliveros.

35. Oliveros, Pauline. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. Universe Books, 2005.

36. Pasos a una mirada trans [Steps Towards a Trans View]. Directed by Damaris Benavides, Havana and Matanzas groups, 2023.

37. Pegadas a mi alma [Stuck to My Soul]. Directed by Maydi Bayona Estrada, Havana group, 2023.

38. Pel·lícula de les mans [The Hands’ Film]. Directed by Beth Johnston, Emma Flynn, and Úna O’Sullivan, Glasgow Group, 2023.

39. Rodríguez, Rosana Paula, and Sofia Da Costa. “Descolonizar las herramientas metodológicas. Una experiencia de investigación feminista.” Millcayac - Revista Digital de Ciencias Sociales, vol. 6, no. 11, 2019, pp. 13–30, revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs3/index.php/millca-digital/article/view/2242.

40. Sennet, Richard. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. Yale UP, 2023.

41. Sierra Liriano, Raquel. “Desarrollan el Panel Cine Dialógico en Festival de Cine de La Habana (+Fotos).” Tribuna de La Habana, 15 Dec. 2023, www.tribuna.cu/cultura/2023-12-15/desarrollan-el-panel-cine-dialogico-en-festival-de-cine-de-la-habana-fotos.

42. Solanas, Fernando E., and Octavio Getino. “Hacia un tercer cine. Apuntes y experiencias para el desarrollo de un cine de liberación en el tercer mundo.” 1969. Cine Club, year 1, no. 1, 1970. Published in English as “Toward a Third Cinema.” Translated by Julianne Burton, Movies and Methods: An Anthology, edited by Bill Nichols, U of California P, 1976, pp. 44–64.

43. Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” eFlux Journal, no. 10, Nov. 2009, worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_94.pdf.

Suggested Citation

Archibald, David, and Núria Araüna Baró. “Unfinished Thinking and the Unfinished Film: Feminist Filmmaking in Cuba, Catalunya, and Scotland.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 165–182. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.09

David Archibald teaches Film Studies at the University of Glasgow. Among other things, he works with Núria Araüna Baró on Ragged Cinema, a feminist-socialist film collective.

Núria Araüna Baró teaches Audiovisual Communication and Media Studies at the University Rovira i Virgili (URV). Among other things, she works with David Archibald on Ragged Cinema, a socialist feminist video collective.