Cosmologies of the Living Forest: For a Metabolic Documentary

Dennis Hippe

[PDF]

Abstract

This article traces Swiss researcher and video artist Ursula Biemann’s use of sound and image in her video works Forest Law (Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, 2014) and Forest Mind (Ursula Biemann, 2021) to understand their aesthetic and epistemic envisioning as a plea for a metabolic documentary. Biemann films with the Indigenous people of Kichwa and Inga (territories of Ecuador and Colombia) who participate in international conferences and workshops on ecopolitics. With the aim of creating through aesthetic practice “new neural synapses that stimulate a more interconnected worldview” through aesthetic practice, these projects encounter Indigenous cosmologies from Latin America. By focussing on how disparate cosmologies are confronted with one another in Biemann’s videos, the article analyses the aesthetic and epistemological ways in which the interconnection of all life is portrayed: while Forest Law observes the hegemonic history of Indigenous knowledge production being suppressed by the Global North, Forest Mind excavates the converging aspects between the Inga’s cosmology and contemporary neuroscience. Reading Biemann’s metabolic documentary as ecocentric cinema, the article outlines the potential of this filmic practice for epistemic justice in the Amazon.

Article

On 27 June 2012, a landmark court case ends at the Inter-American Court for Human Rights: the Case of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku v. Ecuador. The Indigenous Sarayaku won their legal dispute against Ecuador, within whose borders their territory is located. Since the 1960s, the Sarayaku’s rainforest territory has been exploited and reduced in size by international agitators. The US-based firm Texaco has been extracting oil for over three decades there, clearing hectares of rainforest for its more than nine hundred oil pumps. The infrastructure required for these commercial interests destroyed the habitat of countless living creatures. In order to establish trade relations with the US and to obtain funds for the eventual armed conflict against neighbouring Peru, Ecuador allowed Indigenous habitats to be destroyed. The Ecuadorian state sold drilling rights to Texaco on the land the Sarayaku had inhabited for longer than the borders of Ecuador have existed. The colonial wounds left by global capitalism in this area can still be felt today. The tree population as well as the biodiversity of the Ecuadorian rainforest have shrunk massively; the groundwater is polluted over large areas; drought and forest fires have increased. But the rainforest’s natural resources are by no means exhausted and international corporations are still interested in extracting oil reserves and soils from these Indigenous areas.

The verdict won by the Sarayaku marks a legal turning point in this ongoing colonial history: the forest was acknowledged as a juridical subject. It was thus granted legal rights that had previously only been granted to individuals of other species—above all humans. The ruling was not based on market economy or Christian values (often going hand in hand in South America’s colonial history), but on the recognition of Sarayaku cosmology. Sarayaku activists and international experts explained a worldview to the court that supposedly has no place in a self-proclaimed rationalised dispositif such as the courtroom. Usually, Indigenous legal cases are circumvented by the cultural hegemony in legislative institutions of the Global North, making a dialogue between different “paradigms of truth” impossible (Kolowratnik). But things turned out differently: the Sarayaku concept of the “living forest” was acknowledged by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to the extent that a violation of the woods was recognised as bodily harm. The right to bodily integrity, cultural identity, and legal protection were violated. The vitality of the living forest of the Sarayaku was accepted by the court. The colonial wounds of oil extraction are now officially considered to be gaping flesh wounds that the state of Ecuador not only deliberately and negligently tolerated but also profited from financially for decades.

The legal approval of the forest as a living entity in the Case of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku v. Ecuador has been the starting point for Swiss researcher and video artist Ursula Biemann’s artistic and political engagement in the Amazonian area. With the aim of creating “new neural synapses that stimulate a more interconnected worldview” through aesthetic practice (Biemann, Forest Mind), her installation projects Forest Law (Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, 2014) and Forest Mind (Ursula Biemann, 2021) engage with Indigenous cosmologies from Latin America and their struggles against hegemonic epistemic pressures from the Global North. I trace Biemann’s use of sound and image in these two video works to understand how they envision an interconnected worldview based on the premise of all life being existentially intertwined. Thereby, I outline the aesthetic and epistemic operations of what I call—inspired by Desiree Förster’s concept of metabolic aesthetics—the metabolic documentary.

Metabolisms

Since the turn of the twentieth century, the concept of metabolism has been at the core of the Global North’s approach to understanding the functions of the human body. In biochemistry, metabolism describes the overall energy cycle of an organism, which includes the conversion of energy from nutrients and the energy used to process substances. Every organism uses a large part of its functions for a complex network of metabolic pathways, as it is dependent on a constant supply of energy and on the functioning of metabolism for its own survival. Metabolism as a cyclical system thus becomes the basis of the living organism. At the same time, however, it is metabolism that challenges the boundaries of this autonomously conceived organism: the energy and substances that are to be metabolised in the individual in order to continue living must be absorbed from the environment. When biochemists define living beings as “ordered systems that exchange substances with their environment and require energy to maintain their existence”, they make it clear that the existence of these living beings is dependent on the ability to be in constant exchange with the environment (Von Der Saal 6; my trans.). Therefore, metabolism denies a clear Cartesian separation of human and world on an existential level. A living being can only be alive because it is interwoven with its environment, because it exchanges energy with it. This applies to the food intake of a human being as well as to the photosynthesis of a banana plant. Thinking with and through metabolisms thus offers an opportunity to look at processes that constitute an entity as such and to blur these boundaries at the same time. This existential interconnectedness is the core ontological premise of a metabolic perspective on life.

Within the last decade, the metabolic has become a widely used figure of thought in the Humanities and Cultural Studies, from socioeconomic perspectives analysing human history as a social metabolism (Molina and Toledo) and architectural considerations examining building materials and construction substances in the cultural metamorphoses of meaning (Moravánszky), to decolonial positions in curatorial and educational museum planning that think of the museum as a body and deal with its connection to human and nonhuman bodies moving within it (Deliss). In the field of Film and Media Studies, however, thinking with and through the metabolic is not so well established, limited to fields such as the study of technological gadgets monitoring the human body (Denson), or archival theory (Mende). In all of these studies, there is not only an inherent connection between the constituent parts of what is thought of as metabolic networks, which enables them to continue to exist together. Additionally, the cyclical nature of this interconnectedness is repeatedly emphasised; it is never a matter of mere exchange or transfer. Rather, the interaction of energies is always based on a process of transformation within the individual links, which in turn requires and initiates the transformation between the links and, eventually, of the whole system. The metabolic is thus not only characterised by cyclical interconnectedness, but also always links this dimension to a transformative exchange within and between the systems involved. This is the specificity of the human–world relationality outlined by thinking in and through metabolisms. But does this relationality also have a specific potential when it comes to generating and passing on knowledge? What dimensions of meaning open up when we become aware of metabolic interdependencies? What epistemological capacity does the metabolic possess?

In her book Aesthetic Experience of Metabolic Processes, Desiree Förster not only analyses art installations that focus on metabolisms but also establishes the concept of “metabolic aesthetics”, which focuses on these questions. If a metabolic process is experienced aesthetically, it has the potential to make us aware of our own relationality to the environment, constituted by existential intertwinings. For Förster, this aesthetic dimension of the metabolic always has an epistemic dimension since “the aesthetics of metabolism [...] concerns meaning that arises in the environment through the intensified relations between sensing bodies and spatial surroundings” (14). Through the conscious—but no less bodily—interweaving with the environment, the “metabolic subjectivity” achieved through aesthetic experience, as Förster calls it, is opened up to ways of gaining knowledge in which the human subject is not the only actor in the production of meaning. Förster proposes “understanding this orientation as a practice of re-imagining our relation to the world based on a foundational interrelatedness through shared metabolic pathways” (43). The re-experiencing of metabolic processes thus becomes a reconfiguration of the production of meaning. In this perspective on the metabolic, the interrelatedness of humans and the environment goes hand in hand with the interrelatedness of aesthetics, perception, and knowledge.

In contemporary anthropological works on Amazonian communities, this interspecific coproduction of meaning and knowledge has been excavated as one of the core principles of Indigenous cosmologies. Whether in Eduardo Kohn’s seminal monograph How Forests Think or in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s discussion of the concept of “perspectivism”, it becomes clear that in various Indigenous communities in the Amazon, what I have outlined as metabolic principles are lived realities that need no further explanation or conceptualisation. Likewise, the people appearing in Biemann’s films need no one to give them a voice or agency, since they already participate in political engagements and discussions all over the globe.[1]

Therefore, neither Biemann’s work nor this article attempts to appropriate or immerse themselves in the Indigenous cosmologies with which they engage in a way the anthropological “going native” would try to do. Instead, they focus on relating and confronting their own cosmological background with alternative ones. Being aware of the hegemonic histories those cosmologies have with one another, opening up one’s own perspective should finally lead to a provincialising stance that acknowledges the missed potential and previously unseen connections a shared approach to life can offer. Both Biemann’s work and this article aim to reflect on possible affinities and contact zones between their own Western epistemic socialisations, Indigenous cosmologies, and how they can be aesthetically disclosed. The metabolic seems to be a suitable approach for this endeavour since its origin and establishment in a particular local scientific history locate the target audience for this intervention. Simultaneously, it tries to avoid the appropriation of Indigenous terms and some new materialists’ tendencies toward “Romantic invocations of Indigenous life” by relating the learnings from these cosmologies back to this established concept, revealing its hidden but already therein incorporated potentials of realising the interconnectedness underwriting life on this planet (Luciano 19). Biemann’s films seem to be a fruitful starting point for discussing the capabilities and pitfalls of such an idea, advocating for what I call an ecocentric cinema, questioning fixed positions around culturalisms that limit the category of documentary to an inherently colonial and imperialist standpoint, without denying the histories that are undoubtedly linked to these attributes.

Forest Law: Contesting Cosmologies

In 2014, Biemann and San José-based architect and scientist Paulo Tavares launched the installation Forest Law. The main components of this installation, which was first shown in Zurich and has since been exhibited all around the globe, are a multichannel video and a bilingual book project (Biemann and Tavares, Forest Law). While the book Forest Law takes a primarily historical approach to the connection between colonialism, cosmology, and the juridical, the video focuses entirely on the current situation of the Sarayaku and their territory. Nevertheless, the whole project deals with a cosmological conflict, or, as Biemann puts it: “Ultimately, it is a conflict between the Western cosmology, in which the earth is understood as a resource and corporate property, and the cosmology of the Indigenous people, who know that they are part of these ecologies and depend on them” (Biemann and Tavares, “Gespräch” 5; my trans.).

It represents Biemann’s first, but by no means last, work in the Amazon rainforest, while Tavares had already realised several projects about this region and its inhabitants in the Anthropocene before. Both had previously worked on projects that explored how ecology as a political intervention could destabilise hegemonic and exploitative conceptions of nature through aesthetic practices (Biemann et al.). The starting point for the project was a joint close reading of Michel Serres’ book Le Contrat naturel (The Natural Contract), which seemed to have gained new relevance in light of the judgment won by the Sarayaku. With funding from Michigan State University’s Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, Biemann and Tavares went on an excursion to the rainforest on Ecuadorian territory to explore the ongoing extractive colonialisation of Indigenous lands. On the day of their arrival a conference on the Shuar territory was taking place to shine a light on the recent murder of an Indigenous activist. Moved by the testimonies of the various Indigenous communities, Biemann and Tavares started to engage in conversations and to conduct interviews (Biemann and Tavares, “Gespräch” 4–6).

The Sarayaku territory is a remote location without capitalist infrastructure connecting it to the official Ecuadorian community (Biemann and Tavares, Forest Law 29). Therefore, the filmmakers were reliant on the intellectual as well as geographical guidance of Indigenous representatives from the start of the project. The artists’ book reflects far less on these dependencies than that of the follow-up project. Nevertheless, it becomes clear that the Sarayaku strictly regulate access to their lifeworld and cosmology for non-members of their community. After victory in their legal battle, the Sarayaku have been even more interested in representing their agency with collaborators from the Global North toward audiences who are uneducated about the circumstances and existential urgencies in the Amazon and who won’t find their way to the Indigenous activists’ conferences or social media channels. Biemann and Tavares’ project appeared to be an opportunity for the Sarayaku to reach different audiences and galvanise political support for the whole region. To this day, Forest Law continues to circulate primarily in group exhibitions within the European and North American art world, conveying to audiences of the Global North the “sense how the forest is a multi-tiered source of life, yet one that also exists as a physical, legal and cosmological entity” (Gómez-Barris 105). The material gathered during the filmmaker’s research and published around the video is meant to be used by Indigenous activists for their political interests (Biemann and Tavares, “Gespräch” 7).

Forest Law contrasts two divergent epistemic practices. How knowledge is acquired in both cases is distinguished aesthetically. On the one hand, there is what I propose to call an extractive-forensic epistemology. Two characters appear in front of the camera as representatives of this “school”. One is Donald Moncayo who works at a white plastic table in the middle of the green forest (Fig. 1).[2] His white lab coat and white breathing mask repeat and reinforce the chromatic distancing from his surroundings. He takes soil samples, arranges them with utensils on the table, and makes notes on his white pad of paper. The transparent jars on the table, which contain parts of the extracted soil, symbolise the epistemic premise of this action: extraction and visualisation in a setting that is as “clean” as possible. The almost fetishised desire for objectivity, which requires a meticulous separation from the environment approximates the performance of a rapture that materialises in each object and gesture. Ostensibly the basic prerequisite for gaining knowledge, this kind of scene portraying the extractive-forensic epistemology is among the only scenes in Forest Law in which music can be heard. There are mystical sounds which carry the scenery further away—not in the direction of the desired objectivity, however, but into the unreal and obscure. The dissonant clusters that accompany the images of removal and visualisation exoticise this way of gaining knowledge, marking it as an alien element in the living forest. It is clear that the Amazon is an “occupied forest” not only in terms of physical presence but also on an epistemological level (Gómez-Barris).

Figure 1: Donald Moncayo during his forensic performance in Forest Law

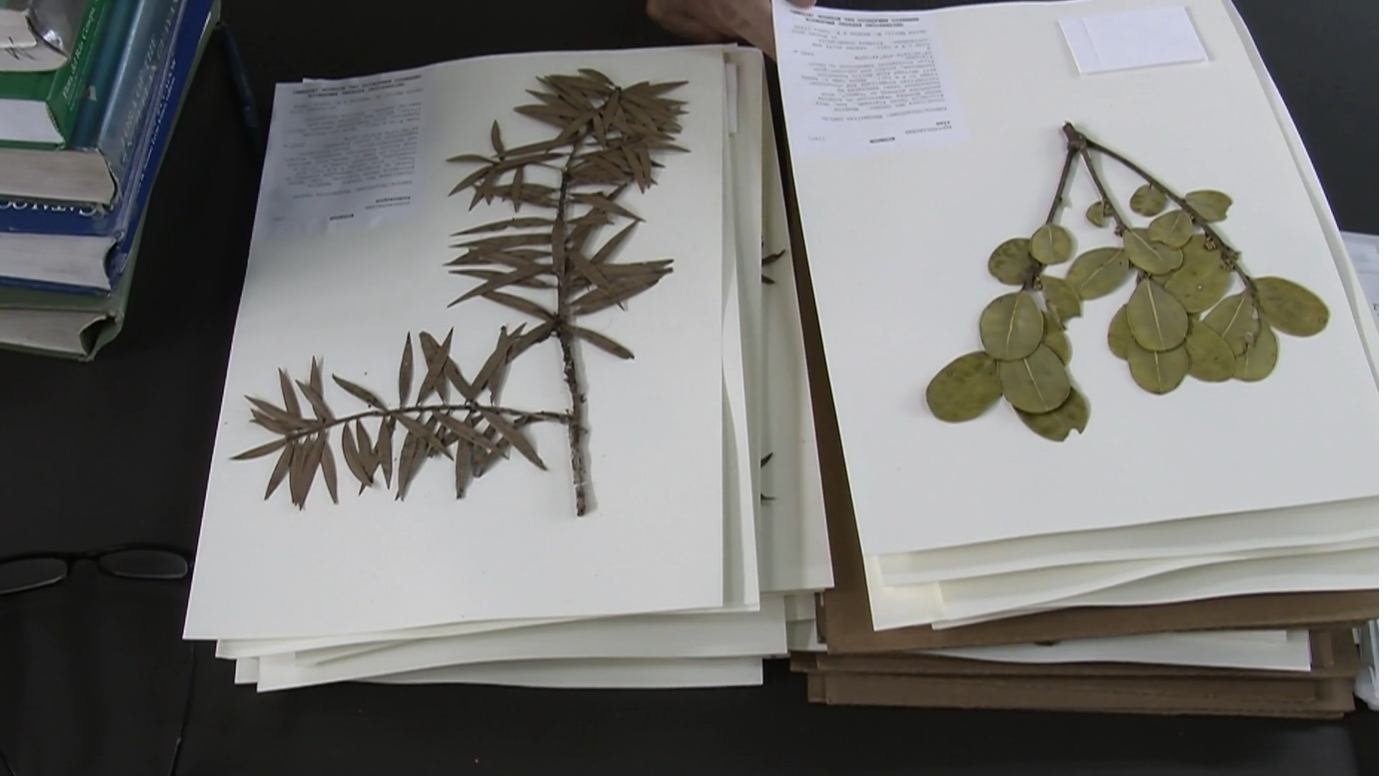

(Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares). 2014. Screenshot.Botanist David Neill is also part of this extractive-forensic epistemology. The US-American has been researching the flora in Ecuador for several decades and his work is funded by international research institutions and universities. He is the only person in Forest Law who is not interviewed in the midst of the forest but in his office, books piled up on his desk, no background noise to be heard. He talks about how fascinated he is by the biodiversity of the Amazon rainforest and how many plant species there are for him and future generations of researchers to discover. He reflects on the ambivalence of his stay in Ecuador: for him, the accessibility of the undiscovered is linked to the infrastructures that institutions install to exploit the forest. Accessibility thus goes hand in hand with destruction. A glance at what lies on the desk in front of him makes it clear that Neill is nevertheless part of the extractive-forensic epistemology: in his herbarium, the collected plants and leaves are arranged, labelled, and presented in a clean, distanced manner (Fig. 2). Discovering, describing, naming, organising: these are the epistemic operations with which Neill encounters the notably numerical richness of the forest to quench his classical thirst for “discovering” the “order of things” (Foucault). Filling the classificatory blanks is his life’s work; extracting, visualising, and separating are its essential approaches.

The second epistemological tradition portrayed in Forest Law is contrasted with the extractive-forensic one. Julio Tiwiram is a shaman of the Shuar and in this role responsible for the healthcare of his people. The biological knowledge about the plants and their powers is acquired through dialogue between humans and the forest and is passed on in his family from one generation to the next. As his worktable reveals, the practice of collecting plays a central role in his work (Fig. 3). To do this, he searches, feels and tastes. However, the composition of the image makes it clear that some of the operations we saw in Neill’s herbarium are missing here: Nothing is labelled, and the sorting does not follow the strict rules a clean setting would demand. Here, too, things taken from the forest are presented to the camera, but in an intuitive, organic way. The collected objects do not have to be clearly separated from one another. Nor do they have to be clearly distinguished from the environment they originate from.

Figure 2: David Neill’s herbarium in Forest Law. 2014. Screenshot.

Figure 3: Julio Tiwiram’s collected plants and herbs, presented on his worktable in Forest Law. 2014. Screenshot.

The epistemic difference becomes even clearer in scenes that show Julio Tiwiram at work. Filmed from a fixed perspective, he disappears and reappears with jump cuts through the forest. Collecting is an act of embodied knowledge; it is lived expertise requiring no classificatory measures in order to function. At this point, I do not want to attribute the colonial violence of exoticisation to the merging of people with their environment—as Karine Bertrand’s critical intervention would suggest (267). I do not want to read into these scenes the politically oppressive gesture of an imagination of the Global North that would like to see ideas of “savagery” or “primitiveness” confirmed. In contrast to the scenes of extractive-forensic production of meaning, there is no use of music. Instead, the sounds of the forest shape the soundtrack. No voiceover interprets the procedure that we can observe here, but it is the voice of the woods that is present, commenting on and directing the images. “Life is semiotic” is the emphatic ontological aphorism from Kohn’s How Forests Think. The living itself provides interpretation, intentionality, and representation. The organic nature of this lived epistemology arises from the harmony in which human and nature work hand in hand, root in root, leaf in leaf. There is no clean, objectivity-suggesting alien element at work. It is the interdependence between human and forest that makes knowledge possible. This knowledge is acquired and implemented bodily. The collector and the collected remain part of the cyclical exchange system that interweaves knowledge and energy. By juxtaposing these practices with those of the extractive-forensic epistemology, showing the interconnectedness of the lifeforms appearing on screen and mediating their codependent and co-constitutive existences, Forest Law makes this epistemic experience of the living forest aesthetically intelligible.

The same happens in the Sarayaku interview scenarios, which take centre stage in Forest Law. Interviews are perhaps the simplest form of knowledge reproduction that documentary and, above all, journalistic practices entail: experts convey their expertise through words; the authenticity of what is said seems assured. Interview situations therefore seem to be the least metabolic thing that documentary has to offer. In these scenarios, who could be interwoven with what? However, looking at the interviews in Forest Law, one thing stands out: the high depth of field which is very uncommon in journalistic interviews. After all, it is taken for granted that the interviewees should be set apart from their background, especially through a shallow depth of field. This should allow us to concentrate on the talking heads since the blurred background cannot distract us from the words being spoken. But precisely because the interview shots in Forest Law would be such poor newsreel footage, they hold a metabolic potential. As with the shots of Julio Tiwiram collecting, the Sarayaku speakers appear in front of the camera on an equal footing with the forest surrounding them. While José Gualinga outlines how the forest is enmeshed in all aspects of his life, his left hand, emphasising the words spoken and central arguments, is not the only thing moving in the rhythm of the thoughts expressed; fern fronds and leaves express their affirmation and support of his words in the same manner as the human body does. The high depth of field allows us to recognise and attune visually to those movements (Fig. 4). In these medium shots, which encompass more space and thus frame the speaker’s body in the context of the natural environment more comprehensively than the typical close-ups for “talking heads”, the focus is literally not on the human individuals alone. Their anecdotes about the legal trial, their explanations of the colonial experience and their fabulations on the cosmology of the living forest are mixed with the equally loud sounds of the life in and of the woods. The Sarayaku and the forest are interviewed simultaneously, describing their shared experiences at the same time. As such, it becomes possible to trace the energy and nonlinguistic semiotics that emerge from and permeate these concurrently appearing elements throughout the entire visual and acoustic space of the interviews, allowing us to observe the distributed agency of the living forest. It is the existential interweaving between human and environment communicating to us, creating a new chronotope of the Amazon through “vegetal storytelling” of a shared history and present (Russell). The image and the soundtrack capture the inseparability of the instances to be seen and heard, allowing them to appear as a coherent organism in these interview scenarios. In this way, the interviews do not serve to represent people as distinct subjects who have a voice and a territory. Rather, an epistemic agency is expressed here that embodies their cosmology and makes it perceptible.

Figure 4: Interview with José Gualinga in Forest Law. 2014. Screenshot.

Through these aesthetic practices, Forest Law captures the interconnectedness of humans and the world. It renders the ongoing interspecific exchange of the living forest through its metabolic pathways aesthetically perceptible and thus stimulates forms of knowledge production among audiences in the Global North that contest those represented by the performances of Moncayo and Neill originating in Cartesian philosophy. This existential dimension of life provides the basis for the metabolic aspect of Forest Law’s documentary method: it makes this interweaving of organisms intelligible and opens up epistemic potentials through aesthetic operations. This documentary mode ostensibly constitutes a “natural”, more existentially precise form of meaning production. Tavares sees the project as an intervention in the regime of perception: by “using artistic means of expression”, Forest Law intends “to close the gap between nature and our Western society, which have long since ceased to coexist in harmony” (Biemann and Tavares, “Gespräch” 9; my trans.) and thereby activate a new experience of one’s own relationality to nature. By conveying a sense of the living forest aesthetically, the work of Biemann and Tavares tries to pull down the hegemonic stance of the Global North’s cosmology and works toward a position that allows for dialogue with others. The metabolic documentary in Forest Law is Biemann’s first attempt to initiate an “interconnected worldview” by means of aesthetics, to address the colonial wounds of the rainforest aesthetically, and take a first step toward “epistemic justice”.

Forest Mind: Converging Cosmologies

The question of how artistic research can be an act of reparation and initiate epistemic justice is the starting point of Biemann’s follow-up project in the Amazon, Forest Mind, primarily funded by the Swiss Arts Council and by the Art Museum at the National University of Colombia. Similar to Forest Law, this video installation was first shown in Zurich and continues to circulate primarily in the art world of the Global North. Starting in 2018, Biemann has worked with the Inga people, an Indigenous community in today’s Colombia, on a project that aims to establish an Indigenous university on Inga land. Biemann is one of numerous artists and scientists from the Global North who were invited by the Inga to materialise this “Indigenous Biocultural University”. In this endeavour, the Inga assigned Biemann the tasks of documenting the project’s development, archiving knowledge, raising funds, and forging partnerships with scientific communities. Forest Mind is one of Biemann’s publications originating from this project, searching for decolonial, nonextractivist forms of aesthetic and epistemic collaboration between the Inga’s and Global North’s cosmologic understandings (Biemann, Forest Mind 17–23).

Led by Hernando Chindoy, former governor of the Resguardo Indígena Inga de Aponte (Aponte Indigenous Reserve) and scholar as well as political activist for traditional Inga medical knowledge, Biemann once again explores the extractive colonial histories of the Amazon and gets introduced to a particular cosmology: the Inga concept of the “master plant”. Even more than Forest Law, Forest Mind focuses “on the interconnection of all life”, as the subtitle of the written work indicates. Therefore, juridical questions get pushed into the background by ontological and epistemological concerns in order to create a “biosemiotics project, a bio-video-essay on the intelligence of nature and the interconnection of all life, taking into account the active, performative role images play in merging mind and forest” (Biemann, Forest Mind 27). Again, cosmologies are confronted with each other. But while the colonial wounds inflicted by the Global North’s scientific self-as-universal-understanding in the Amazon during the Anthropocene are discussed historically in great detail, Forest Mind is particularly interested in the connections between the Inga’s understanding of the world and contemporary findings in “Western” science that are concerned with relationality amongst living beings.

Like its predecessor, Forest Mind focuses on interviews in which the Inga talk with their environments to the camera, explaining their shared cosmology and history of oppression. This time, the ways of lived communication between different species within the network of livelihoods is discussed in more detail: a major role is attributed to the Ayahuasca plant, an autochthonous liana (or vine) with which generations of Indigenous people in the Amazon have engaged. The Quechuan name refers to the liana of the soul, the dead, or the spirit. From the Global North’s perspective, this plant is called “Banisteriopsis caapi” while Ayahuasca is considered to be a hallucinogenic brew of which the liana is only one part. This linguistic difference carries a cosmological implication: referring to a manufactured substance, Ayahuasca becomes an epitome of the Global North’s “syntax for the composition of the world” with its constituting dichotomy between the natural and the cultural (Descola 127). Thus, Ayahuasca is understood to be a cultural phenomenon with a history distinct from the natural, while the Quechuan understanding of the word makes no such differentiation and allows for a shared semiotic connection with nonhuman entities.

As Chindoy explains in one of Forest Mind’s interviews, in the Inga cosmology, Ayahuasca becomes the central instance for experiencing this semiotic interrelatedness. The Inga think of the liana as the “master plant”, a teaching entity that enables the people ingesting it to communicate with the territory around them which turns out to be a relational field of cobeing and counderstanding. Ayahuasca is the physical and cognitive substance connecting all lives that are part of this territory and therefore existentially linked to one another through this master plant. As a narrating voice concludes: “the master plant has a mind. It also has semiotic agency and intention. When ingested, the plant evokes a feeling of social belonging and trust within a social group. It is a psycho-integrator plant, mediating a fully embodied thinking-feeling-knowing-imaging. It is a thinking with earth.” Through the metabolic process of ingesting and digestion, this shared coexistence is not only experienced but also connected to an epistemological dimension, since taking ayahuasca is seen as an entry point to a meaningful communication with entities which are neither less intelligent nor less articulate than the ones considered to be human. On the contrary, as a teacher, ayahuasca transmits knowledge to the Inga about the healing potentials of other plants and about their existence in the Amazon. Learning through engaging with this network of life by ingesting the master plant has become a key aspect of the knowledge the Inga have gathered for generations. Similarly to Gregory Bateson’s conception of the mind as a relational category, Ayahuasca enables interspecific meaning making and intelligence through metabolic processes.

Understood as a biosemiotic process, a constitutive biological and biochemical intercellular communication in and between lifeforms, Biemann is interested in exactly this aspect of interspecific meaningful interactions. For Inga shamans, knowledge can only be gained through a bodily conversation that requires understanding the other as an entity with intentionality. Engaging in a meaningful relation with subjects such as the master plant is a constitutive factor of knowledge and cobeing. This epistemological conviction can only function in a cosmology based on what Philipe Descola calls “animism”, in which all living beings are equipped with kindred cognitive capabilities but have different appearances; they have a similar interiority while having a dissimilar physicality (122).[3] Thereby, the distinction between culture and nature as well as teleological hegemonies between phenomenologically different kinds of beings collapse due to the shared capabilities of all lifeforms that have a soul and can form meaningful relations with another. Communicating and learning with and from other species is essential for cosmologies based on animism. In such cosmologies, social, ethical, and political kinship inherently overcome boundaries between species (Haraway).

However, instead of cleaving to Descola’s distinction between Indigenous animism and “Western” naturalism, Forest Mind searches for connections between the described form of knowledge production and those currently present in the natural sciences of the Global North, using biosemiotics as a bridge between those cosmologies. Biemann is particularly interested in new findings in neuroscience and microbiology concerning the interaction of mental and physical capacities for the purposes of biosemiotic artistic research. On the one hand, the question of signalling amongst plants is a current issue in biology. Understanding natural lifeworlds as connected networks in which interaction, transmission, and communication take place is especially prominent in biological research on fungi. The idea of the “wood wide web” and its discovery of mycorrhizae as the key communication entity amongst plants and fungi in forests in the late 1990s can be seen as a huge step for Global North science toward an ecocentric understanding of the world (Simard et al.). The research on mycorrhizae indicates that the metabolic system of the forest is based on a complex network of plants which communicate their needs and offerings amongst each other to secure a shared survival of the biosphere (Simard et al.). In this respect, biosemiotics and metabolism are similarly bound together as they are in the Inga cosmology.

On the other hand, Forest Mind is highly concerned with recent developments in DNA research. Not only do the ground principles of DNA hint toward a shared organic composition of all lifeforms, research on the memory functions of DNA has been of increasing interest within recent decades. Highly influencing the idea of biocentrism, DNA is the most effective storage material for memory (Lanza and Berman), which can be seen as a move toward the acknowledgement of Kohn’s aforementioned aphorism, “life is semiotic”, within modern biochemistry. The discovery of the “biophoton” is yet another step toward biosemiotics as a key principle of life in the Global North’s life sciences. According to biochemical findings, these special kinds of photons, with ultraviolet frequencies ranging from 10−17 to 10−23 W/cm2, are emitted by every organism. Over the course of the twentieth century, a wide range of biochemists has dealt with the role of biophotons for cell communication. In the field of quantum physics, it is the energetic part of DNA that stores this information. Consequently, organisms communicate and exchange information through the emission of biophotons. In Forest Mind, this leads to the most significant parallel between contemporary developments in the Global North’s sciences and Indigenous involvement with Ayahuasca: in order to consciously engage with this communicative flow of information, you have to attune to a layer of semiotic interaction (Narby). For numerous generations, the Inga have done this with the master plant, while the Global North was too entangled with Cartesian philosophy to even imagine, let alone pursue this kind of knowledge acquisition.

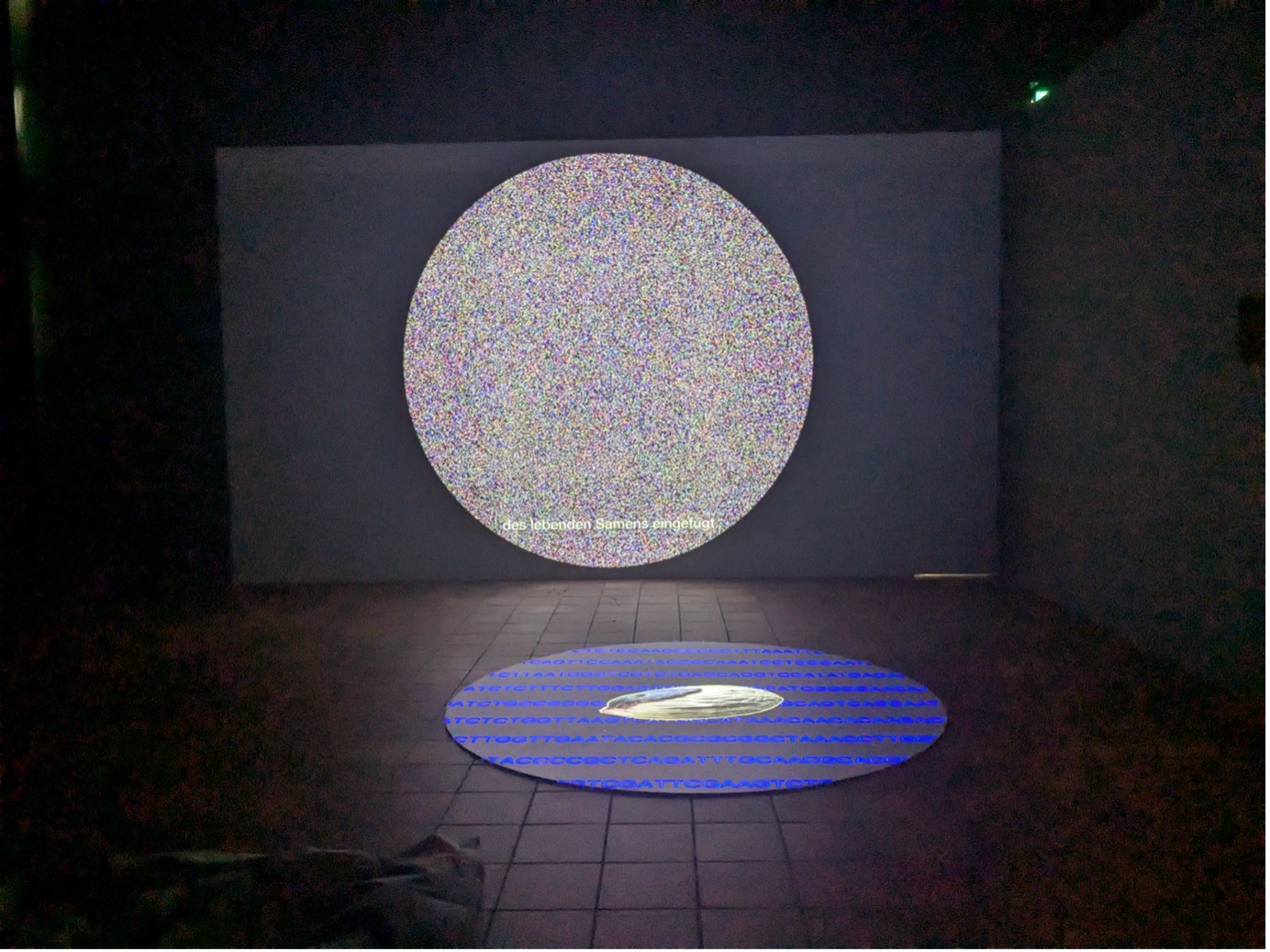

Forest Mind tries to reconcile these convergent cosmologies by imagining these possibilities artistically. The images of interviews and the Amazon are continually intertwined with visualisations—orbs composed of bulks of red, blue, green, and white circles as well as bubbles branching infinitely with other bubbles through bulky arms.[4] These animations are produced by DNA sequencing at ETH Zurich, a practice used by various European and US-run biotech enterprises in the Amazon to extract information from this living forest for pharmaceutical and nutritional purposes. Using this process for aesthetic rather than financial ends, Biemann used the archiving capacities of the DNA to combine materials she collected in the rainforest. The new, unique double helix is a material reconfiguration of amalgamated videographic, sonic, and organic information relying on the knowledge-storing capabilities of life. Eventually, the colour-emitting DNA strand was filmed and the visual output of this binary-to-biological transcoding produced the animation (Biemann, Forest Mind 106–19) (Fig. 5). Later on, this DNA was blended into the ink that was put onto the walls around the installation and used for the book cover of Forest Mind.

Figure 5: Animation of the biophoton emitting, sequenced DNA, consisting of visual, auditory,

and organic material from the Amazon. Photograph of the installation Forest Mind(Ursula Biemann, 2021) in Senckenberg Nature Museum, Frankfurt, taken by the author in July 2024.

The images and sounds of the living forest, the digital recording of its herbal, human, and atmospheric layers of being are no longer the only techniques of presenting and representing it. The visual field is enriched by depictions of the (intra)microbial layer of existence within this interspecific network. Evolving from the interview scenarios of Forest Law, the signs and acts of co-constitutive knowledge transfer throughout all the elements appearing within the frame have now materialised with additional visual techniques. Simultaneously to the talking people, the affirming leaves, grasses, and trees, next to the multilayered thought-articulating soundscape of the forest, bubbles of the formerly unseen permeating energies and meanings appear on screen. The Inga’s animist ontology is depicted by animations created with the Global North’s state-of-the-art scientific technologies and procedures. The Indigenous knowledge and lived reality of the interconnecting capabilities of the mother plant is thus articulated with techniques used for observations about biophotons in European scientific institutions. Combining them in the same frame not only allows for a dialogue between these two cosmological certainties but also emphasises the affinities between them.

In addition to hearing the different instances of the living forest-entity, the communication systems between them are made visible: the bioneural networks and the biophotons emitting DNA strands are now phenomenologically perceptible. As a result, the metabolic interview scenarios introduced in Forest Law are extended to a microbiological and submolecular layer of communication. For Biemann, “writing the living forest and its sonic and pictorial representation into the same genetic code, effectively collapses the distinction between life and its representation” (Forest Mind 121). With this animation, the biosemiotic endeavours of Forest Mind reach their artistic and epistemological peak, creating a newly imagined and realised form of experiencing the interconnectedness of all life through artistic practices, being fertilised by different but in this instance converging cosmologies.

Coda

As Amitav Ghosh argues, to really grasp the degree of the Anthropocene’s disastrous impact on all life, people in the Global North require cultural production that is able to attune them to the “force of unthinkable magnitude that creates unbearably intimate connections over vast gaps in time and space” (63). As their everyday life lacks the capacity to illustrate this impact, their cosmology is not able to realise these vital connections they share with others and how dependent everyone on this planet is on one another. Aesthetic practice focusing on these relationships between lives can therefore be a crucial device for acknowledging political and ethical responsibilities. Starting at a familiar existential principle but subsequently opening up toward uncertainties, the metabolic documentary has the potential to activate the political and ethical consciousness of its audience in this manner.

Additionally, Biemann’s metabolic documentaries situate themselves within the “urgent need to embrace greater epistemological diversity and thus to advocate for greater epistemic justice” (Forest Mind 128). They imagine a critical alternative to recent conceptualisations of epistemic attunement to nature that turn to German Romanticism and thereby disregard the role of this epoch for the establishment of the nineteenth century’s division between nature and culture and within the solidification of Cartesian philosophy (Taylor; Bohnenkamp-Renken et al.). They advocate for interepistemological and intercosmological cooperations which, by focusing on the interconnectedness of life, are more reparative than the established positions that build their political endeavours for the environment upon reconfigurations of institutional structures of the Global North (Latour 91–127). Over the course of the last decade, Biemann repeatedly came to Indigenous territories in the Amazon to be educated by the living forest and the people who are part of it. The collaborations resulted in a turn from a depiction of contrasting cosmologies in Forest Law to Forest Mind’s imaginative exploration of the converging features of them. “In drawing on autochthonous epistemologies”, Biemann is one of the numerous contemporary “filmmakers and artists [who] are breaking away from the dominant Western visual regime that has opposed animate and inanimate beings, landscapes and human figures” (Brenez et al. 35). The video and installation works, made for audiences in the Global North whose cosmologies are inherently connected to this visual regime, but who are nevertheless part of the same metabolic network of the planet, emerge in a time where the colonial exploitation of lands presumably far away from these audiences continues to trigger existential tipping points. Questioning the histories of cosmologies and opening up their current state for connections with different epistemic traditions is one step toward imagining and practising a shared future on and with this planet. The metabolic documentary offers one way to attune our interrelated bodies and minds to this end by making this status quo of life intelligible.

To really make this metabolic documentary an act of epistemic justice, other practices within and beyond the analysed installation projects for the Global North must be enacted: practising interviews as a form of citation, not exploitation; walking on paths guided by Indigenous people instead of using the comfortable ones smashed into the forest by extractive corporations; publishing the work at least bilingually… All these considerations become even more complex in Biemann’s ongoing project Devenir Universidad, an artistic and archival documentation of the Inga’s efforts to build an Indigenous university on and out of their territory. Testing the limits of the metabolic documentary in the realm of this struggle to institutionalise intercosmological knowledge production by imagining the Indigenous scientist as a crucial figure for the establishment of a liveable future (Biemann, “Forest”), the project will show how far epistemic justice and decolonial collaboration between Indigenous cosmologies and artists, scientists and scholars from the Global North in the region of the Amazon can be realised. Nevertheless, Ursula Biemann’s metabolic documentary, envisioned as a form of ecocentric filmmaking, can be seen as one step toward this mission.

Notes

[1] Representatives of the Sarayaku travel to international conferences and roundtables on nonhegemonic and decolonial approaches to Indigenous territories. Inga representatives continuously engage in transcultural discussions on Ayahuasca, such as the International Ayahuasca Conference.

[2] Donald Moncayo is an Indigenous activist. The scene described here follows one of his numerous performances illustrating the irreversible impact Texaco’s drilling has done to the environment—even to areas of the Amazon which are not subject to contracts between the company and Ecuador.

[3] For the relation between animism and Viveiros de Castro’s perspectivism, see Descola (138–43).

[4] In the multichannel installation version of Forest Mind, these images appear simultaneously on the various screens adjacent to one another.

References

1. Bateson, Gregory. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. U of Chicago P, 2000.

2. Bertrand, Karine. “From Pierre Perrault to Rolf de Heer: Auteur Cinema and the Poetic Exploration of Indigenous Lands and Identities.” Cinema of Exploration: Essays on an Adventurous Film Practice, edited by James Leo Cahill and Luca Caminati, Routledge, 2020, pp. 266–79.

3. Biemann, Ursula, director. Devenir Universidad. 2018–ongoing, deveniruniversidad.org.

4. ——, director. Forest Mind. 2021.

5. ——. Forest Mind: On the Interconnection of All Life. Spector Books, 2022.

6. ——. “The Forest as a Field of Mind.” Quaderni Culturali IILA, vol. 4, no. 4, Feb. 2023, pp. 21–30, https://doi.org/10.36253/qciila-2059.

7. Biemann, Ursula, et al. “From Supply Lines to Resource Ecologies: World of Matter.” Third Text, vol. 27, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 76–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2013.752199.

8. Biemann, Ursula, and Paulo Tavares. “Ursula Biemann & Paulo Tavares im Gespräch mit Lina Louisa Krämer.” Enter the Void 10/07–01/11/20 Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Ursula Biemann, Forensic Architecture, Paulo Tavares Gespräche/Interviews. Kunsthalle Mainz, 2020, pp. 4–8.

9. ——, directors. Forest Law. 2014.

10. ——. Forest Law—Selva Jurídica. Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, 2014.

11. Bohnenkamp-Renken, Anne, et al., editors. Wälder: Von der Romantik in die Zukunft. Freies Deutsches Hochstift / Frankfurter Goethe-Museum / Senckenberg Museum / Museum Sinclair-Haus, 2024.

12. Brenez, Nicole, et al. “‘What’s the Point of Cinema?’ Struggles, Conviviality, and the Vivacity of Images.” Film X Authochtonous Struggles Today, edited by Nicole Brenez et al., Sternberg Press, 2024, pp. 8–47.

13. Deliss, Clémentine. The Metabolic Museum. Hantje Cantz, 2020.

14. Denson, Shane. Post-Cinematic Bodies. meson press, 2023, https://doi.org/10.14619/0436.

15. Descola, Philippe. Beyond Nature and Culture. Translated by Janet Lloyd, U of Chicago P, 2013.

16. Förster, Desiree. Aesthetic Experience of Metabolic Processes. meson press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.14619/1808.

17. Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Pantheon Books, 1970.

18. Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. U of Chicago P, 2016.

19. Gómez-Barris, Macarena. “The Occupied Forest.” The Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change, edited by T. J. Demos et al., Routledge, 2021, pp. 100–05.

20. Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822373780.

21. Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Case of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku v. Ecuador. Judgement of June 27, 2012 (Merits and Reparations). Inter-American Court of Human Rights, 2012.

22. Kohn, Eduardo. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. U of California P, 2013.23. Kolowratnik, Nina V. The Language of Secret Proof: Indigenous Truth and Representation. Sternberg, 2019.

24. Lanza, Robert, and Bob Berman. Biocentrism: How Life and Consciousness Are the Keys to Understanding the True Nature of the Universe. BenBella Books, 2010.

25. Latour, Bruno. Politics of Nature: How to Bring Sciences into Democracy. Harvard UP, 2004.

26. Luciano, Dana. How the Earth Feels: Geological Fantasy in the Nineteenth-Century United States. Duke UP, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478027843.

27. Mende, Doreen. “The Undutiful Daughter’s Concept of Archival Metabolism.” E-Flux, vol. 93, 2018, pp. 1–11, http://worker01.e-flux.com/pdf/article_215339.pdf.

28. Molina, Manuel Gonzalez de, and Víctor M. Toledo. The Social Metabolism: A Socio-Ecological Theory of Historical Change. Springer, 2014.

29. Moravánszky, Ákos. Metamorphism: Material Change in Architecture. Birkhäuser, 2017.

30. Narby, Jeremy. The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. Penguin, 1999.

31. Russell, Catherine. “Amazon Cinema: Vegetal Storytelling.” Cinema of Exploration: Essays on an Adventurous Film Practice, edited by James Leo Cahill and Luca Caminati, Routledge, 2020, pp. 228–43.

32. Serres, Michel. The Natural Contract. Translated by Elizabeth MacArthur and William Paulson, U of Michigan P, 1995, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9725. Originally published in French as Le Contrat naturel, Éditions François Bourin, 1990.

33. Simard, Suzanne W., et al. “Net Transfer of Carbon between Ectomycorrhizal Tree Species in the Field.” Nature, vol. 388, no. 6642, Aug. 1997, pp. 579–82, https://doi.org/10.1038/41557.

34. Taylor, Charles. Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment. Harvard UP, 2024.

35. Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Cosmological Perspectivism in Amazonia and Elsewhere: Four Lectures given in the Department of Social Anthropology, Cambridge University, February–March 1998. HAU, 2012.

36. Von Der Saal, Karin. Biochemie. Springer, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-60690-2.

Suggested Citation

Hippe, Dennis. “Cosmologies of the Living Forest: For a Metabolic Documentary.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 92–108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.05

Dennis Hippe M.A. is a research fellow and PhD candidate at the DFG-funded research training group “Configurations of Film” at Goethe University Frankfurt. He studied Film Studies and Audiovisual Publishing at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. His research focuses on issues of scientific film, documentary filmmaking, media witnessing, and the production of filmic knowledge. In his dissertation project, he combines these elements to explore the estate of volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft.