From Thailand to Colombia: Soundscapes of a Violent Past in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria (2021)

Javier Pérez-Osorio

[PDF]

Abstract

Memoria (2021) is Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s first film made outside his native Thailand. The director’s geographical origin, the Colombian setting, and the extensive international funding make the film a singular transnational production. The global and local elements embedded in both the narrative and the production history open a space for critical examination of the geopolitical interconnections between the Global North and South, and between two diverse Global South countries—Thailand and Colombia. Considering the film as a crossroads of different discourses, I analyse its innovative approach to the Colombian context, seeing it as the result of a journey of several months made by the director through the country, a dynamism later echoed both by the mobility of the main character and by the singular model of exhibition chosen for the film. I propose that the perspective of a foreign auteur from a different Global South context offers a novel view on Colombian collective memory of historical violence. I further explore how this transnational blend is echoed in the film’s meticulous sound editing and meditative framing. Finally, I suggest how Memoria transposes local trauma into a broader idiom of “global” art cinema, reformulating the exchanges shaping Latin American international coproductions.

Article

“Sound is the last sense to go when you die holding hands” (Weerasethakul)

The history of Colombian cinema is characterised by persistent depictions of the multifaceted iterations of the nation’s civil conflict. The first feature film ever produced in the country, El drama del 15 de octubre (Francesco Di Domenico, 1915), recreated the violent assassination of Rafael Uribe Uribe, a renowned political leader and veteran of a brutal civil war, La guerra de los mil días (1899–1902). The film was produced by Italian brothers Francesco and Vicenzo Di Domenico, who pioneered the film industry in Colombia in the early twentieth century. Interestingly, the portrayal of the local conflict through the lens of filmmakers from other countries has been a recurring motif since the inaugural film by the Di Domenico brothers. From now-classics such as Canaguaro (1981) by Chilean filmmaker Dunav Kuzmanich and A Man of Principle (Cóndores no entierran todos los días, 1984) by Colombian-Belgian Francisco Norden, to more recent representations such as Maria Full of Grace (Joshua Marston, 2004) and Dirty Hands (Manos sucias, Josef Kubota Wladyka, 2014), this external perspective on Colombia has become an integral part of the cinematic discourse about the nation for decades. These depictions, nonetheless, have largely relied on stereotypical representations of the Colombian context, often resorting to overt portrayals of violent acts and oversimplifying the structural origins of the conflict. This approach not only emphasises the visual spectacle of violence but also merely scratches the surface of a complex war.[1]

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria (2021) stands as a significant deviation from this dominant approach. Although the film is not strictly about the Colombian conflict, the Thai director’s first film made outside his native country does not escape the inevitable social and political tension that has dominated the lives of those living in the South American country. Memoria proposes an innovative perspective on this setting, distancing itself from an overt representation of the horrors of war. Instead, Apichatpong explores through the language of art film the nuances underpinning a history of violence that reverberates in Colombian history and land. Deploying a deliberately loose and slow narrative, the film tells the story of Jessica, an expatriate Scottish woman played by Tilda Swinton, who lives in Medellín and runs a local flower business. While visiting her convalescent sister in Bogotá, Jessica starts hearing a disturbing sound, a loud bang, initially at daybreak. Soon, she realises that the sound is not produced by the builders next door, as she initially thought, and that only she can hear it. Troubled by it, Jessica embarks on a journey to understand the noise in her head that sounds like “a rumble from the core of the Earth”. In the process, she first befriends a young sound engineer, Hernán (Juan Pablo Urrego), and later an archaeologist who studies precolonial human remains discovered in a remote area of Colombia. Travelling to the excavation site, Jessica finally achieves a sense of clarity about herself and the sound she has been hearing (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Jessica (Tilda Swinton) in her quest for the origin of the loud bang in her head.

Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul). Kick the Machine, 2021. Screenshot

Memoria is, on the one hand, the existential and healing journey of Jessica, whose exploration of the bustling streets of Bogotá and the serene and haunted landscapes of Pijao in rural Colombia evokes Apichatpong’s well-known fascination with the liminal spaces between wakefulness and dream, and between life and death. On the other hand, as in films by Apichatpong such as Tropical Malady (Sud pralad, 2004) and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Loong Boonmee raleuk chat, 2010), the personal journey of the main character alludes indirectly to crucial political and social matters like the legacies of armed conflicts. In Memoria, using Jessica’s singular condition and journey across an unknown territory, the director explores Colombia’s troubled memory of the crimes committed, not only within the recent civil conflict but extending as far back as the violent legacies of the Spanish colonisation. The result is a singular portrayal of Colombia, which is all at once familiar and unknown to the local spectator.

Memoria, nevertheless, is not made primarily for a Colombian audience. Premiered at Cannes in 2021, where it won the Jury Prize, the film’s aesthetic form, which follows Apichatpong’s characteristic slow cinema and long takes, more clearly presupposes the specialised audience of the international film festival circuit. In addition to Apichatpong’s reputation in the circuit, this aspect of the film is highlighted by Tilda Swinton’s role in the conception and realisation of the film, the first overt artistic collaboration of the Thai director. Swinton, who moves smoothly between mainstream and art-house cinema, has been an important figure in experimental filmmaking since her debut with Derek Jarman, a former and fundamental artistic partnership in Swinton’s career that, according to her, is similar to the one she now has with Apichatpong (Kay). Additionally, as much of the independent filmmaking from the region that is exhibited chiefly at festivals in the US and Europe, Memoria was funded by capital from a wide range of countries, from China, the UK, and Qatar to Colombia, Mexico, and Thailand.

The geographical origin of Apichatpong, the Colombian setting, and the long list of countries funding it make Memoria a singular transnational production. The global and local elements embedded within both the film’s narrative and its production history offer an opportunity for critical examination of the geopolitical interconnections between the Global North and the Global South, and between two diverse Global South countries—Thailand and Colombia. Considering Memoria as a crossroads of different discourses, in this article I analyse its innovative approach to the Colombian context, and see it as the result of various journeys made by the director through the country, during which he actively listened to the population, a dynamism later echoed both by the mobility of Swinton’s character in the narrative and by the singular model of exhibition chosen for the film. I also propose that the approach of a foreign auteur from a different Global South context produced a novel perspective on the Colombian collective memory of historical violence. Furthermore, I explore how this transnational blend is echoed—quite literally—in the film’s meticulous use of sound editing to broaden the significance of the main character’s psychological landscape, which, in turn, is entangled with Apichatpong’s meditative framing of the Colombian backdrop. Finally, I propose that Memoria transposes the representation of local trauma to a broader idiom of “global” art cinema that resignifies and exceeds the boundaries of the Latin American continent, at once reformulating the exchanges at play in the international coproductions that have dominated the continent’s cinema.

“She Walks, Sits, and Listens”: Making a Film in a Foreign Country

Apichatpong began to contemplate the idea of making a film in a different country after the possibility of working on his own terms in Thailand became increasingly restricted (Hosoki). During the production of Cemetery of Splendour (Rak ti Khon Kaen, 2015), the military seized control of the government in his home country, making it unfeasible to pursue projects that hinted at criticism of authoritarianism. At the same time, since the director befriended Swinton over a decade ago, both envisioned the possibility of developing a project together. From the inception, there was no established plan, as the Scottish actor explains: “We had this very open and relaxed idea of making a film with absolutely no prescription about narrative or even place, about a kind of atmosphere of receptiveness, a sort of suspension. We had this agreement to make a film about that atmosphere” (Kay). The decision about the location for the film was made when Apichatpong visited Colombia in 2017 for a retrospective of his work organised by the Festival Internacional de Cine de Cartagena de Indias (FICCI). After participating in the event, the director spent three months travelling the country, where he was struck by its volatile climate, mountainous landscapes, and the underlying sense of mystery that seemed to permeate its atmosphere. Suddenly, through this initial opportunity to wander across Colombia and converse with the local population, the details of Memoria’s plot started to emerge.

The process of visiting Colombia “several times in chunks of time” (Kay) with deliberate openness and curiosity is essential to understand the creation of Memoria, its loose plot and emphasis on listening. This artistic wandering through an unknown land, according to the director, “allow[ed] me and Tilda to be strangers, to operate with the idea of not knowing, with open senses” (Kay). Memoria was, then, from the very beginning a film about looking and listening, a sort of cinematic meditation (Rithdee). Through this process of wandering and observing the surroundings, the connection with the filmmaker’s native country also became apparent:

While I was in Colombia, I felt a strong connection to my native Thailand. The more you find out about the country and the more you talk to people, the more you start to see that, behind the bright colours, lies something unresolved from the past. […] Both countries are trying to move ahead but are stuck in the past. In Thailand, there is a complicated political situation whereby people who were murdered or “disappeared” by the military regime still haven’t been recognised, while the people that were responsible for their murders are now in positions of authority. Colombia has experienced similar chapters in its history. (O’Connor)

The time spent in Colombia helped Apichatpong not only to establish connections between his homeland and the South American nation but also to develop a deep understanding of the country. Such attitudes of wandering and listening explain the film’s innovative approach to the country’s conflict. The director’s outsider perspective led to a more nuanced engagement with Colombia, one that foregrounds the intimate experiences and emotional realities of both a first-time observer and longtime inhabitants, a blending of perspectives that usually is avoided in mainstream narratives. Additionally, the traumatic past of both countries, viewed through Apichatpong’s unique lens, creates an unprecedented connection between these two culturally distinct contexts that are geographically distant but geopolitically—and now filmically—close as parts of the Global South.

The filmmaking process of Memoria followed the experiential journey of the director in Colombia in the years before making the film, as well as that of the lead actor during the shooting. Shot chronologically from August to October 2019, the production unfolded as the filmmaker and Swinton immersed themselves in Colombian culture. This methodological approach facilitated the reflective exploration of Jessica’s evolving sense of her true identity—and the cause of the bang in her head—and her transformative interaction with the nation’s people, a process echoed by the film’s deliberate slow pace and the prominence of silence and ambient soundscapes over dialogue (Fig. 2). As Apichatpong explains, “[T]hrough the working process, I didn’t know what I wanted to achieve. […] I think Tilda also approached the film the same way: just being present in the moment” (Hosoki). Ultimately, Memoria became a filmic meditation on the intense experience of both internal and external realities evoked by the Colombian context.

Figure 2: Jessica (Tilda Swinton) is shown attentively listening and observing her surroundings.

Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul). Kick the Machine, 2021. Screenshot.

In Apichatpong’s mind, this fundamental aim of creating a character that is intentionally present in the moment is directly connected with her initial inspiration for the film: Memoria’s Jessica is an iteration of Jessica Holland, the comatose character played by Christine Gordon in Jacques Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943). Following this model from classical horror, the Thai filmmaker created his Jessica through a very simple prism: “She walks, sits, and listens” (Weerasethakul). Hers is an attitude that the filmmaker associates with a certain spiritual dimension of cinema: “It’s about how you position yourself in the world—again, in your environment—and just make everything without having a concrete flow. It’s more about flowing and whatever comes” (Prakash). As will be revealed by the end of the film, the bang in Jessica’s head is an effect of her being a vessel for the traumas of others, her ability to “embody the melancholy of strangers” (Weerasethakul). Following his practice of not providing much information about his characters’ motivation or background, Apichatpong confessed that he “didn’t know how long Jessica had lived in Colombia, who her husband was, what she needed to accomplish in Bogotá, how big was her orchid in Medellín, what kind of car she drove” (Rithdee). Jessica is indeed devoid of conventional personality traits, rendering her a conduit for the experiences, silences, and historical ghosts that permeate the film’s plot and the Colombian context. Thus, as a result of her wandering and listening, Jessica becomes attuned to the vibrations of memory and pain buried in Colombia’s land. Through this lens, she emerges as a resonant body, facilitating a dialogue with the spectres of history and conflict.

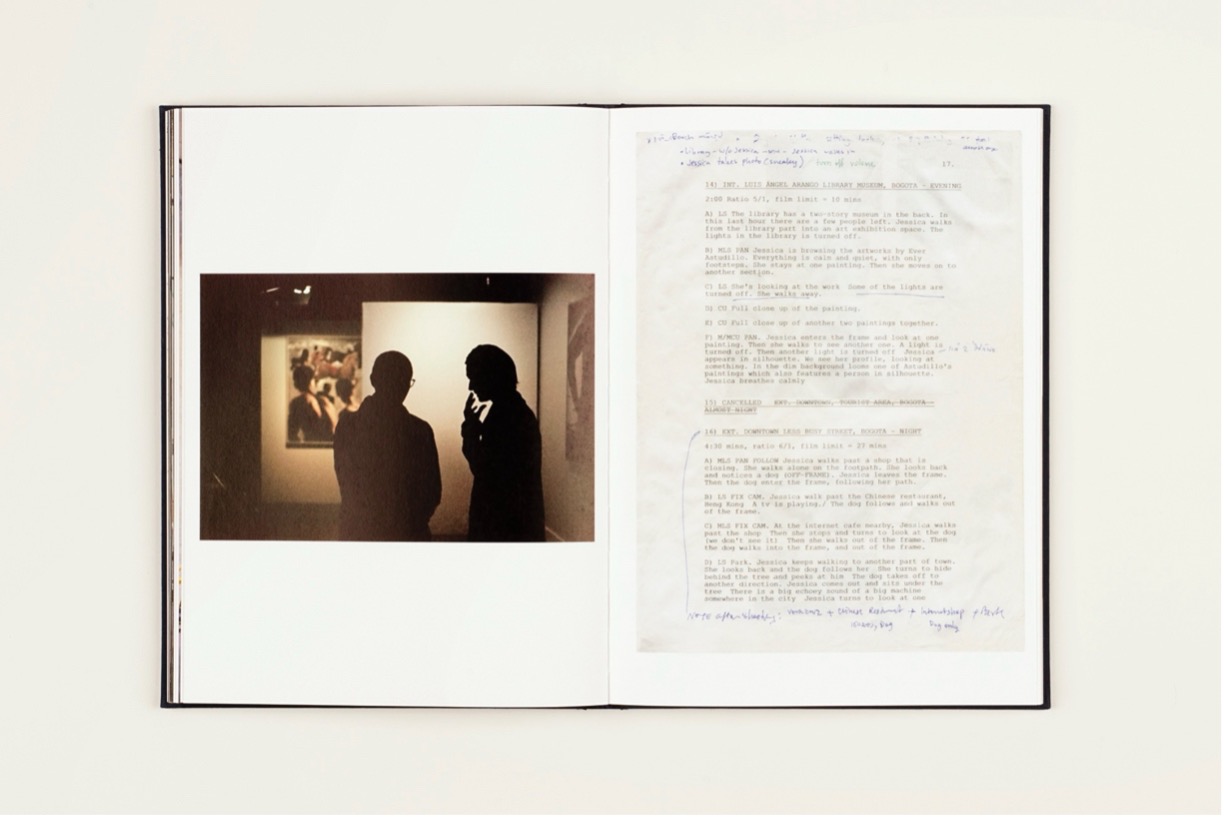

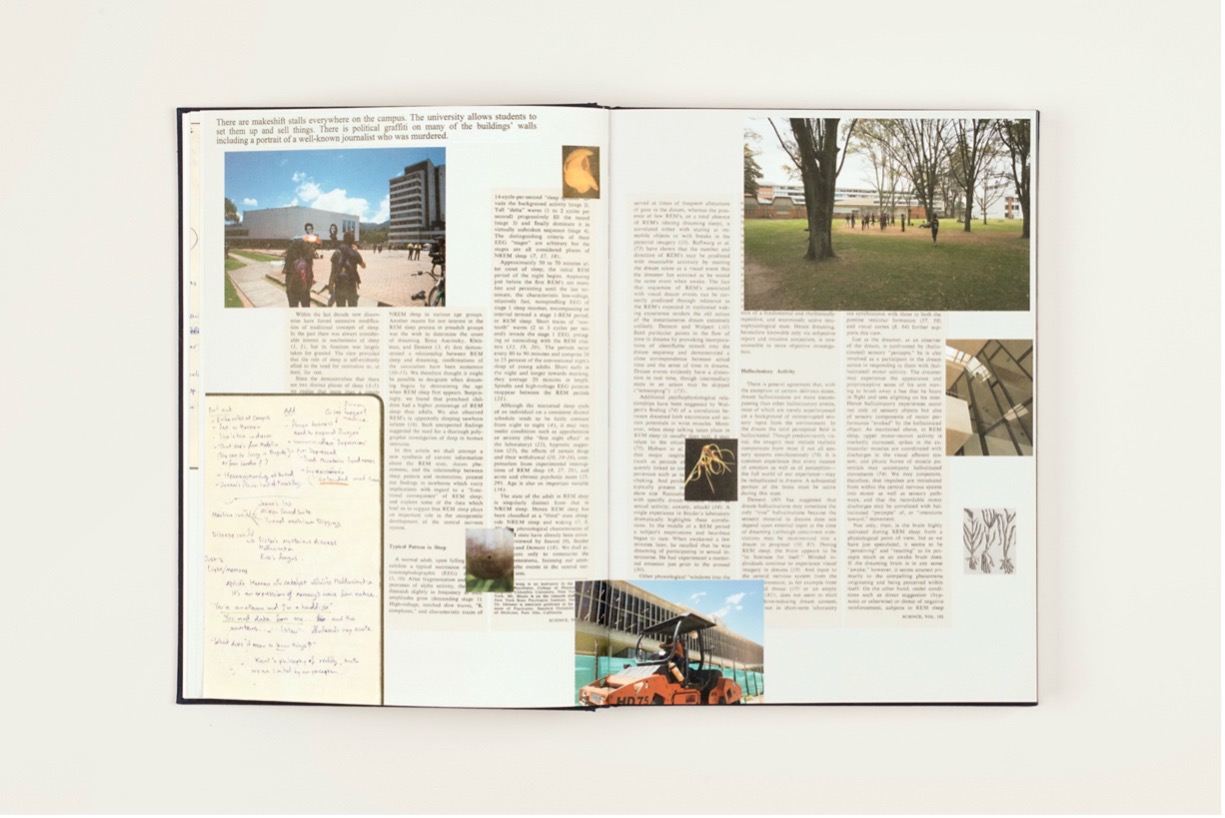

The filmmaking process and Jessica’s essential attitude of wandering and listening are also expressed in the book about the film, an object that attests to the notable multidisciplinary and intermedial profile of Apichatpong. Published by Fireflies Press, a German-based independent publisher specialised in contemporary cinema, the book registers the genesis and creation of Memoria. It is a beautiful, colourful, and artistic publication that gathers “the memories [Apichatpong] collected, in the form of photographs, a personal diary and sketchbook, research notes, treatment excerpts, and email correspondence” (Fireflies Press). A brief plot description by the director at the beginning of the book is followed by an interview with Swinton and a diary of the shooting. All these are placed alongside exclusive materials from the production, such as set photographs, annotated pages of the script, and storyboard panels (Fig. 3). What fascinates me in this object, and seems essential to understanding the film, is the hundreds of annotations about the Colombian context in Apichatpong’s notebook and the shooting diary, capturing the defining features that underpin the film, from the seemingly unlimited biodiversity of the country to its diverting takes on the political process of constructing the memory of the recent conflict (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 (above): Photographs of Apichatpong and Swinton during the shooting and annotations

on the script are included in the book Memoria by Fireflies Press (2021).

Figure 4 (below): The director’s personal diary, observations about locations, and research about Colombia’s biodiversity are also included. Courtesy of Fireflies Press.

The real-life and narrative wanderings that characterise the film found a striking parallel in Memoria’s distribution and exhibition strategy. Rather than opting for a conventional, simultaneous release in multiple locations and theatres, the film was shown in a single-screen tour, moving from city to city like a cinematic apparition (Kay; Hudson). This nomadic circulation mirrors the film’s own narrative drift and its resistance to fixed meanings or locations. In this way, the exhibition method becomes an extension of the film’s logic: a journey rooted in slowness, attention, and attunement. The essential attitudes of wandering and listening that inform the narrative become the key to understanding the film, its profilmic reality, and extradiegetic meaning. Such an overarching approach, in turn, informs the most relevant formal choice of the film alongside its slowness, namely, its striking sound design, to which I will now turn my attention.

Haunting Soundscapes: Reverberations of Colombian Violent Past

Memoria opens with a mysterious and sonically shocking sequence that foreshadows the whole film. An initially undecipherable silhouette appears at the foreground of a dimly lit room, shrouded by the heaviness of a profound stillness and silence. After almost two minutes of this quietness, without any warning, a loud bang shatters the tranquillity of the scene, awakening what is now clear to be a sleeping figure. The person—soon to be revealed as Jessica—slowly stirs in the darkness and moves to the curtains, attempting to discern the source of the sound. No immediate answers are provided for either the character or the audience. It is only at the film’s conclusion, after a prolonged journey, that an explanation is suggested.

As the opening sequence evinces, the focus on sound is integral to Memoria. From the beginning of the project, such emphasis was clear, as Apichatpong has explained that the idea of Jessica’s mental bang comes from his personal experience of Exploding Head Syndrome, the sensory condition in which people “hear” loud noises in their heads, especially in moments of light sleep at dawn (Crosbie-Jones). Although in the director’s case the condition was accompanied by some type of colourful hallucinations, he decided not to include any visual elements in the film and instead opted for creating a mental soundscape.[2] Such a decision became even clearer in the postproduction process, as Apichatpong emphasises: “Through the working process, I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to achieve. I didn’t know the heart of the film, collecting sound, until the point of editing and sound design and I started to know better” (Hosoki). This resulted in a film that, instead of showing, allows the audience to experience the feelings of itinerancy, displacement, and uncertainty of the main character primarily through the sound design.

The emphasis on sound also comes to the forefront thanks to the limited use of spoken language. In the film, even though the sparse conversations usually occur in Spanish and, occasionally, in English, the director favours long scenes primarily consisting of static shots with no dialogue, in which Jessica simply walks and attentively listens. Such formal decisions parallel Apichatpong’s and Swinton’s knowledge of the local language while they were in Colombia. Even though the filmmaker took language lessons, working in Spanish became a creative opportunity, as he has stated: “I enjoyed so much working in a language I couldn’t properly speak; it became music” (Rithdee). This language barrier also highlights the importance of listening and observing beyond the spoken word, emphasising the idea of a sensorial experience above all.

The Thai filmmaker’s fascination with sound and its creative potential in cinema is not new. Apichatpong’s enduring collaboration with the sonic artist and sound designer Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr is well known and has been integral to the filmmaker’s work since Tropical Malady. In a 2013 article, Philippa Lovatt explores this artistic partnership focusing on the director’s installations, short films, and long features. Lovatt examines how Apichatpong’s work moves from a sound design aligned with classical cinema that normally privileges the voice, to instead favouring a “natural” ambient or environmental sounds—almost denaturalised and disconnected from the images—to heighten the affective power of sound (62). Importantly, Lovatt highlights how Apichatpong and Kalayanamitr’s sound design—beyond a representational paradigm—correlates to processes of memory and remembering. The author “explores the materiality of sound […] in an attempt to understand, not what these sounds might ‘represent’, but how the affective power of the sound design might capture a sense of how it feels to remember” (64). This is what Lovatt calls the “mnemonic potential of the sonic”, channelled through a sound design that “expresses what the process of remembering feels like, how the warp and weft of the past continuously moves through and shapes the present just as the present shapes our memories of the past” (63). One can trace this sonic focus in Memoria as well, a film that, borrowing Lovatt’s foreshadowing words, foregrounds an emotional appeal that “transcends, or perhaps rather circumvents, language—privileging instead the epistemology of embodied memory” (67).

Apichatpong’s attention to sound in Memoria also aligns with the increased interest in the role of sound in capturing the relationship between landscape, memory, and sound in moving image works and scholarship from the last decade (Donnelly and Mollaghan; Davis; Tanner). In the introduction to Haunted Soundtracks: Audiovisual Cultures of Memory, Landscape, and Sound, Kevin Donnelly and Aimee Mollaghan suggest that “the turn of the millennium has heralded a significant outgrowth of culture that demonstrates an awareness of the ephemeral nature of history and the complexity underpinning the relationship between location and the past” (1). Such an interest has prompted a switch in focus when exploring individual and collective memory in cinema, changing the approach “from how audiovisual landscapes can be experienced from one of seeing to one of listening”, allowing for the contact with intangible affective experiences mostly through the sound associated with a landscape (1). Ultimately, for the authors “sound can blur the barriers between interiority and exteriority’ (2).

Apichatpong’s engagement with the Colombian political context in Memoria can be understood through this association between sound, memory, and landscape. The filmmaker’s practice has never been straightforward regarding the political commentary underlying his work. Although all his films up until Memoria are set geographically in Thailand, and temporally in the last three decades, his characters and storylines do not directly represent any of the parties or ethnicities involved in the ongoing political unrest experienced by the country. Instead, the director has employed a prevailing sense of ambiguity to demonstrate—or merely imply—any socio-political stance. In the words of Apichatpong:

The political in my work is something that is hidden, but you slowly become aware of what happened historically in the particular place. For me, that’s a strong way to send a message. If all I wanted was to raise awareness of the history of a place, I could have written a book about it. It would be more direct. When you undertake artistic activities you give importance to the people who survive, or who really bear the history on their shoulders. This fact is already political, and an artist cannot avoid it. (Kim 52)

This is also true for Memoria, a film with significant sociopolitical weight, although it evades any overt insinuation of Colombia’s violent past and present. The Colombian armed conflict was, for a long time, the world’s longest-running active civil war. It officially began in 1964 with the creation of two guerrilla movements, but the violence had started long before (Ríos Sierra). After numerous failed attempts, a successful peace process was initiated in 2012 between the Colombian government and the oldest guerrilla, the FARC, resulting in a final agreement signed in November 2016. Following the peace accord, one of the major commitments was the establishment of the Truth Commission, a transitional institution responsible for reconstructing the historical memory of the conflict from the victims’ perspective (Ríos Sierra). The commission concluded that almost a million people— mostly civilians—were murdered during the conflict and that the government had been significantly involved in some of these crimes (Ríos Sierra). Memoria was filmed during the period when the recently elected right-wing president, Iván Duque Márquez, was contesting the revelations of the Truth Commission and when the nation was polarised regarding the legitimacy of the peace accord, an aspect noted in the shooting diary (Weerasethakul).

Although this backdrop is crucial to understanding Memoria, the film keeps any political commentary well below the surface. It presents a sense of uncertainty and ambiguity regarding the Colombian political background, suggesting a certain vagueness about the subject that ultimately informs Memoria’s narrative. Elements such as Jessica’s insomnia, the recurrent conversations about dreams, and the unexplained disappearance of Hernán, the sound engineer, intensify the sense of disorientation. Although Swinton’s character is ubiquitous, as mentioned, the film reveals little about her background: we vaguely know about Jessica’s past—as if she has no memories of her own—and she does not actively seek anything. Instead, she simply resonates with the environment surrounding her. Even the ultimate answer about the bang in her head seems to be an incidental outcome of wandering through Colombia’s various urban and rural spaces. She resembles running water flowing spontaneously, as Apichatpong poetically describes her (MUBI Podcast). The sound design complements the same narrative vagueness that centres our attention on the atmosphere rather than the images. In addition to the loud bang, the film is filled with noises—mostly, acousmatic sounds—such as barking dogs, car alarms, radio stations, and wild animals that simultaneously root the film in the Colombian context and create an atmosphere of bewilderment.

The fixation with sound is echoed in a very particular self-referential sequence halfway through the film. During the first arc, Jessica enters a modern and minimalist recording studio while Hernán attentively takes notes, listening to a classical music piece. Sitting in the room as he continues to work, Jessica silently joins the session. The frame shows her in the background as she listens, subtly reacting to the nuances of a melodic composition dominated by the sounds of a violin and a piano. Once the song is finished, Jessica approaches the soundboard and reveals the reason for her visit: she is trying to understand the bang in her head. “It’s like a big ball of concrete that falls into a metal well which is surrounded by seawater”, she unhurriedly tries to explain in Spanish. Thereupon, Hernán attempts to recreate the noise using a sound effects library for cinema (Fig. 5). Without any rush, the film takes its time to show how the two characters go through the process of digitally recreating Jessica’s sound as accurately as possible, even though she acknowledges the difficulty because—uttering Apichatpong’s literal words—“it probably sounds different in my head” (Weerasethakul). The filmmaker and Kalayanamitr took around three weeks to recreate the sound and, as echoed in the film, it went from an initial linguistic explanation to a sonic “mountain” in the sound spectrograph (Mankowski). As Lukasz Mankowski highlights in conversation with the film’s sound designer, in the twelve-minute sequence in the recording studio, “we experience the permeability of the sound: its verbal, sonic, and visual layer; lost in translation between the senses and perspectives, we engage, and the body of the film is thus linked to the body of ours.” The pivotal sequence, composed of only three long and static shots, epitomises Memoria’s conspicuous invitation to listen, and Apichatpong’s aim of “[b]ringing the audience into the mixing room and exposing the process” (Kay).

Figure 5: Jessica (Tilda Swinton) and Hernán (Juan Pablo Urrego) in the recording studio.

Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul). Kick the Machine, 2021. Screenshot.

This invitation to listen ultimately creates an empathetic relationship between Jessica and the audience. As viewers, startled from the outset by the bang that only the protagonist can hear, we are compelled by the film to share her intimate experience. The sounds thus bridge the core of the film—Jessica’s journey— and the audience’s perspective. Although there is not a single point-of-view shot in the film, and only a handful of close-ups, it feels as if the spectator is in Jessica’s head all the time. Once this is established, sound editing becomes more relevant concerning the film’s entanglements with Colombian past and present history. Bound to Jessica’s psychological soundscape, Memoria then establishes the connection between this internal world and the context that the main characters have been relentlessly traversing.

In the film’s final twenty-minute sequence, Jessica meets another Hernán (Elkin Diaz) —physically different but probably embodying the same “spirit” of the sound engineer who vanished halfway through the film. Hernán claims to possess the gift of remembering everything he sees, and the memories preserved in the objects around him. He is like the hard drive of the world. During an intense conversation, once again composed of a handful of static shots, Jessica begins to narrate a traumatic experience that indirectly alludes to stories of internal displacement in Colombia (Fig. 6). She soon realises this is not a memory of her own but rather that she is accessing Hernán’s memories, drawn from the history of the Colombian land. Jessica discovers that she is like an antenna, able to listen for and connect with others’ memories. Hernán explains that the sound she has heard probably belongs to a time before they both existed. As they sit at the table and the camera focuses on Jessica’s expression, she enters a trance while listening to various sounds and voices disconnected from the small room where they are. Ships coming ashore, screams of pain, and other bangs that could be from mines or crossfire suggest she recalls episodes from the history of colonisation and the recent armed conflict in the country. Finally, the trance ends with the same sound that she has heard all along, originating from a spaceship taking off in the middle of Colombia’s mountains. Nothing is properly explained, but it becomes clear that Jessica can synchronise herself with the trauma buried in the land around her. This aspect becomes even more significant considering that just before her conversation with Hernán, she visited the excavation site where precolonial indigenous remains have been recovered.

Figure 6: Jessica (Tilda Swinton) and Hernán (Elkin Diaz) in the final sequence of the film.

Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul). Kick the Machine, 2021. Screenshot.

Such weaving of the Colombian violent past—which relentlessly quivers in the land—with the soundscape of the film is associated with what Donnelly and Mollaghan define as “psychogeography”, “a desire to consider location and landscape as essentially emotional or psychological objects rather than merely backdrops for drama” (3). This conception in turn recalls Jacques Derrida’s influential concept of “hauntology”, the idea that the past is lingering, alongside all lost futures, in the present (Derrida 9, 202; Fisher; Tanner). A less positivist perspective on history, hauntology gestures towards the spectral remnants of the past within the peripheries of human cultures. Challenging linear and singular interpretations of history, Derrida invites us to trace memories from the past embedded in contemporary contexts as a decisive philosophical attitude (Donnelly and Mollaghan 3). Crucially, it is an invitation to dialogue with that lasting presence from the past:

It is necessary to speak of the ghost, indeed to the ghost and with it, from the moment that no ethics, no politics, whether revolutionary or not, seems possible and thinkable and just that does not recognize in its principle the respect for those others who are no longer or for those others who are not yet there, presently living, whether they are already dead or not yet born. (Derrida xviii)

Along these lines, Apichatpong’s meticulous soundscape underscores the experiences of trauma drawn from the Colombian context, allowing us to listen to the ghosts of the country’s violent past. As Mankowski suggestively describes it, in the final sequence Jessica and Hernán “stay in the present but we inherit the audio perspective of the past so that the here-and-now translates phonically to the here-and-then.” Far from a spectacle of war, Jessica’s role as an antenna—a receptacle of waves of memory—centres us in a space where the past reverberates in the present. We here coincide with Schafer, who has expressed that “hearing is a way of touching at a distance”, this time a way to touch the memories from both recent and distant pasts. Alongside Hernán’s hyperthymesia, Jessica becomes a new iteration of Jorge Luis Borges’s unforgettable character, “Funes el memorioso”: “‘I, myself, alone, have more memories than all mankind since the world began,’ he said to me. And also: ‘My dreams are like other people's waking hours’” (135). Thus, as the psychogeography of Colombia’s traumatic memory—individual and collective—is matched with a soundscape, historical timelines collapse while Apichatpong reminds us that memory is an act of the past taking place in the present and is inevitably connected with the future.

Remapping Exchanges

The incursion of the Thai filmmaker in the Colombian cinematic landscape also creates an opportunity to reformulate the terms of cultural exchange that have shaped Latin American cinema. In the book Latin American Cinema: A Comparative History, Paul Schroeder Rodríguez proposes the continent’s cinema as the result of an uninterrupted triangular exchange of moving images, discourses on modernity, and aesthetic strategies between Hollywood, Europe, and Latin America (2). Recalling Deleuze and Guattari, the author asserts that cinema from the region is “caught up in and forms a rhizome with cinemas in other parts of the world” (294). This blend ultimately has endowed the films with an original set of formal and narrative strategies in which national, continental, and global influences are intertwined. Although it is not easy to classify Memoria simply as a Latin American film—even though it represented Colombia both in Cannes and the Academy Awards—the film allows us to take Schroeder Rodríguez’s argument further.

In a recently published article on the film, Cecília Mello traces the connection between Colombia and Thailand in Memoria, exploring a current trend of incorporating the phantasmagorical into an aesthetics of realism (“Phantasmagorical Realism” 172). Framing it as a sign of the fascination as much as the mistrust of cinema’s indexicality, Mello explains how some contemporary practitioners “go beyond this realist approach by incorporating elements such as ghosts, fantastic beings, unexplainable events and atmospheres of fear into their diegesis” (174). Aligned with the previously invoked Derrida’s hauntology, Mello points out how resorting to “ghosts and haunting in contemporary cinema therefore carries significant social and political implications relating to issues of trauma and memory” (174). In that sense, Mello reasserts the idea that Memoria belongs to a genealogy of phantasmagorical realism, a category coined by the author in 2015 (Realismo). What interests me the most in Mello’s article is that, although this trend is present in cinemas from different parts of the world, she rehearses a comparative analysis of the phenomenon as it occurs in East/South East Asia and Latin America. According to the author, “[t]he paradoxical bond with reality expressed in the formulation ‘phantasmagorical realism’ condenses the real experience of fear in Latin American cities […] and the fears and tensions that emerge from unresolved political violence” in the countries from both regions (“Phantasmagorical Realism” 174).

Extending Mello’s argument, it is possible to understand how Memoria’s formal approach not only establishes a connection between similar haunting realities of its Colombian and Thai settings but also underscores a shared aesthetic perspective, revealing points of encounter in how the cinema from both regions grapple with their historical traumas through a phantasmagorical lens. Without disregarding the role of the Global North’s cultural and financial capital in the production of Memoria, the connection between these distant Global South locations throws into relief the triangular exchange suggested by Schroeder Rodríguez, considering how the influence of Hollywood—and, to some extent, European influence as well—is significantly relegated. This bridging of distant cultural spaces through a shared aesthetic—in this case materialised by Apichatpong’s practice—gives rise to a form of solidarity that is not only embedded in the narrative and style of Memoria but also resonates beyond it. Borrowing Macarena Gómez-Barris’s ideas, Apichatpong entices an interpretation of cinema from the region that moves away from nation-centred approaches and repositions Latin American cinema as an active participant in a transnational sphere of representational politics that forges South–South solidarities (2).

Such unexplored and emerging solidarity ultimately connects with the innovative representation of the Colombian context. Unlike most national and international films that either centre on the country’s armed conflict or use it as a narrative backdrop, Memoria contains few overt visual references to this history of violence. It consciously avoids the tropes of the perilous jungle teeming with armed men that have come to define Hollywood—and at times even local—representations of Colombia. The difference in Apichatpong’s gaze, although also foreign, lies in his refusal to exoticise or essentialise the nation. Instead, the filmmaker constructs a film about Colombia that is shaped by an entirely new set of references, in which the country’s singular history is simultaneously specific and universal. As the director himself stated, “The experience of shooting there has shown me the universality of human emotion. It’s quite reflective of how I approach my past films in Thailand” (Kay).

One can see how Memoria’s vagueness—rooted in both the filmmaker’s and the protagonist’s acts of wandering and listening—enables the memories of those affected by Colombia’s armed conflict to emerge, largely unmediated by the dominant patriotic discourses that typically shape and constrain public understandings of national trauma (Teh 597). This at once quiet and loud divergent depiction of Colombia contributes to a resignification of the country’s collective memory and historical violence, while simultaneously resisting superficial visions of a nation still grappling with its paradoxical international image. Furthermore, Memoria invites a rethinking of how Latin American cinema can be reimagined through the presence of an outsider who refuses to impose meaning and instead engages in a patient act of wandering and listening. By shifting the axis of influence beyond the established triangle of Hollywood, Europe, and Latin America, Memoria proposes a renewed model of cinematic exchange—one grounded in empathy, opacity, and a shared search for meaning across borders.

In conclusion, Memoria’s journey becomes a transnational vehicle that embodies the horrors that have haunted Colombia for decades, not through direct exposition but through the space it creates—an architecture of listening, sensing, and waiting. Apichatpong wandered, together with Swinton/Jessica, in a mode of quiet receptivity, of being-with rather than speaking-for. The slowness of the film reflects the pace proper to taking the time to absorb something horrendous, to carry its weight rather than merely depict it. This temporal drift allows for an ethical stance: one that refuses the spectacle of violence in favour of its echo, its lingering afterlife. The vision of the film is at once from outside and within, “[it] imagines a kind of closeness that comes from distance” (Betancourt 67), continuously oscillating between foreignness and intimacy. The film does not claim any mastery over the Colombian context but attunes itself to the resonances of trauma that pulse beneath the surface of the everyday. In doing so, it crafts a poetics of haunting that respects opacity, embraces ambiguity, and foregrounds the loud echoes of silence and memory over the clarity of narrative closure.

Notes

[1] As recently as 2024, Netflix released the South Korean crime drama, Bogota: City of the Lost (Kim Seong-je), a stereotypical depiction of Colombia in the late 1990s as a dangerous place where organised crime dominates society. The contrast with Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria is even more striking, considering this is also a film by an Asian director set in Colombia.

[2] I understand soundscape in its seminal meaning coined by R. Murray Schafer, as “[t]he sonic environment; […] the abstract constructions such as musical compositions and tape montages” (1). In my analysis of Memoria, I am also influenced by Emily Thompson’s definition of soundscape as “both a world, and a culture constructed to make sense of that world” (1).

References

1. Betancourt, Manuel. “Colombia Enchanted in Memoria and Encanto.” Film Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 4, 2022, pp. 64–68, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2022.75.4.64.

2. Bogota: City of the Lost. Directed by Seong-je Kim, Jaguar Bite, 2024.

3. Borges, Jorge Luis. “Funes, His Memory.” 1942. Collected Fictions, translated by Andrew Hurley, Penguin Books, 1999, pp. 131–37.

4. Canaguaro. Directed by Dunav Kuzmanich, Producciones Alberto Jiménez, 1981.

5. Cemetery of Splendour [Rak ti Khon Kaen]. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kick the Machine, 2015.

6. Chulphongsathorn, Graiwoot. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Planetary Cinema.” Screen, vol. 62, no. 4, 2022, pp. 541–48, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjab058.

7. Crosbie-Jones, Max. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul: How to Deal with Exploding Head Syndrome.” ArtReview, 6 Apr. 2022, artreview.com/apichatpong-weerasethakul-how-to-deal-with-exploding-head-syndrome.

8. Davis, Colin. “Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms.” French Studies, vol. 59, no. 3, 2005, pp. 373–79, https://doi.org/10.1093/fs/kni143.

9. Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. Translated by Peggy Kamuf, Taylor and Francis, 1994.

10. Dirty Hands [Manos sucias]. Directed by Josef Kubota Wladyka, HEART-headed Productions, 2014.

11. Donnelly, Kevin J., and Aimee Mollaghan, editors. Haunted Soundtracks: Audiovisual Cultures of Memory, Landscape, and Sound. Bloomsbury Academic, 2023, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501389580.

12. ——. “Introduction.” Haunted Soundtracks: Audiovisual Cultures of Memory, Landscape, and Sound, edited by Kevin J. Donnelly and Aimee Mollaghan, Bloomsbury Academic, 2023, pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501389580.ch-1.

13. El drama del 15 de octubre. Directed by Francesco di Domenico, 1915.

14. Fireflies Press. “Memoria.” FirefliesPress.com, 2021, firefliespress.com/Memoria-Apichatpong-Weerasethakul. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

15. Fisher, Mark. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 1, 2012, pp. 16–24, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16.

16. Gómez-Barris, Macarena. Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas. U of California P, 2018.

17. Hosoki, Nobuhiro. “Toronto International Film Festival: Memoria: Q&A with Palme D’or Winning Director Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Cinema Daily US, 22 Sept. 2021, cinemadailyus.com/interviews/toronto-international-film-festival-memoria-qa-with-palme-dor-winning-director-apichatpong-weerasethakul-starring-tilda-swinton.

18. Hudson, David. “Memoria Goes on Tour.” The Criterion Collection, 2021, www.criterion.com/current/posts/7562-memoria-goes-on-tour. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

19. I Walked with a Zombie. Directed by Jacques Tourneur, RKO Radio Pictures, 1941.

20. Kay, Jeremy. “In Conversation: Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tilda Swinton on Colombian Mystery Drama Memoria.” Screen Daily, 2021, www.screendaily.com/features/in-conversation-apichatpong-weerasethakul-and-tilda-swinton-on-colombian-mystery-drama-memoria/5165464.article. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

21. Kim, Ji-Hoon. “Learning About Time: An Interview with Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Film Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 4, 2011, pp. 48–52, https://doi.org/10.1525/FQ.2011.64.4.48.

22. Lovatt, Philippa. “‘Every Drop of My Blood Sings Our Song. There Can You Hear It?’: Haptic Sound and Embodied Memory in the Films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” The New Soundtrack, vol. 3, no. 1, 2013, pp. 61–79, https://doi.org/10.3366/sound.2013.0036.

23. A Man of Principle [Cóndores no entierran todos los días]. Directed by Francisco Norden, FOCINE, 1984.

24. Mankowski, Lukasz. “How It Sounds to Remember: The Sonic Work of Akritchalerm Kalayanamitr.” Mubi.com, 4 Apr. 2022, mubi.com/notebook/posts/how-it-sounds-to-remember-the-sonic-work-of-akritchalerm-kalayanamitr.

25. Maria Full of Grace. Directed by Joshua Marston, HBO Films, 2004.26. Mello, Cecília. “Phantasmagorical Realism in Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul 2021).” The Moving Image Review & Art Journal (MIRAJ), vol. 12, no. 2, 2023, pp. 171–88, https://doi.org/10.1386/miraj_00115_1.

27. ——, editor. Realismo Fantasmagórico. Pró-Reitoria de Cultura e Extensão Universitária –USP, 2015, www.livrosabertos.abcd.usp.br/portaldelivrosUSP/catalog/book/816.

28. Memoria. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kick the Machine, 2021.

29. Mera, Miguel, et al., editors. The Routledge Companion to Screen Music and Sound. Routledge, 2017, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315681047.

30. MUBI Podcast Encuentros. “Special Episode: Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria”. Mubi.com, 3 Aug. 2022, mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/mubi-podcast-encuentros-special-episode-apichatpong-weerasethakul-s-memoria.

31. O’Connor, Rory. “Apichatpong Weerasethakul on Why Cinema Should Be Communal.” Frieze, 19 Jan. 2022, www.frieze.com/article/apichatpong-weerasethakul-memoria-2022-interview.

32. Prakash, Inney. “Freedom in a Different Way: An Interview with Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Screen Slate, 2023, www.screenslate.com/articles/freedom-different-way-interview-apichatpong-weerasethakul. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

33. Ríos Sierra, Jerónimo. “¿Una paz fallida? Dificultades de la construcción de paz en Colombia tras el acuerdo con las FARC-EP.” Revista de Estudios Políticos, no. 190, Nov. 2020, pp. 129–63, https://doi.org/10.18042/cepc/rep.190.05.

34. Rithdee, Kong. “Apichatpong’s Memory of the World.” Bangkok Post, 30 June 2021, www.bangkokpost.com/life/arts-and-entertainment/2140839/apichatpongs-memory-of-the-world.

35. Schafer, R. Murray. Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Destiny Books, 1994.

36. Schroeder Rodríguez, Paul. Latin American Cinema: A Comparative History. U of California P, 2016.

37. Tanner, Grafton. “Hauntology.” The Routledge Handbook of Nostalgia. Routledge, 2024, pp. 224–36.

38. Teh, David. “Itinerant Cinema: The Social Surrealism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Third Text, vol. 25, no. 5, 2011, pp. 595–609, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2011.608973.

39. Thompson, Emily. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900–1933. MIT Press, 2004.

40. Tropical Malady [Sud pralad]. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Backup Media, 2004.

41. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives [Loong Boonmee raleuk chat]. Directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kick the Machine, 2010.42. Weerasethakul, Apichatpong. Memoria. Fireflies Press, 2021.

Suggested Citation

Pérez-Osorio, Javier. “From Thailand to Colombia: Soundscapes of a Violent Past in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria (2021).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 203–219. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.11

Javier Pérez-Osorio (he/him) is currently a Lecturer in Spanish and Latin American Studies at the University of Stirling. In 2026, he will start a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship at the University of Edinburgh. His research interests dwell in the intersection between film studies, queer cinema, and decolonial thinking in Latin America. He holds a PhD in Film and Screen Studies from the University of Cambridge. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in publications such as Queer Studies in Media and Popular Culture, The Edinburgh Companion to Queer Reading, and the Bulletin of Latin American Research.