Foreign Body: AIDS, Moral Panic, and Otherness in Via Appia (1989)

Henrique Rodrigues Marques

[PDF]

Abstract

In 1989, Jochen Hick, a prolific German documentary filmmaker, chose Brazil as the setting for the feature film Via Appia, which follows a flight attendant who returns to Rio de Janeiro to find the man who transmitted the HIV virus to him. Despite the low recognition of the motion picture, it is notable in the work of Gustavo Subero that the film continues to be one of the main references in the international context on the crisis of AIDS in Brazil. Starting from a historical survey of Brazilian cinema production addressing the disease in the 1980s, this article proposes an analysis of how Via Appia reinforces foreign discourses and imaginaries about the AIDS crisis in Brazil.

Article

In Gustavo Subero’s book Representations of HIV/AIDS in Contemporary Hispano-American and Caribbean Culture: Cuerpos suiSIDAs, the main work reflecting media discourses about HIV/AIDS in Latin America, the only film representing Brazil is the German production Via Appia (1989), directed by queer documentary filmmaker Jochen Hick. Although, as noted by Robert M. Gillett (“Disavowing” 225), Hick is by no means a household name, his films usually make the niche festival circuit, securing theatrical screenings before hitting the channels of video distribution. Therefore, Hick has some notoriety, at least within queer cinephile circles. Via Appia, his first and one of his only two forays into fiction, was filmed on location in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, Brazil, with dialogues spoken in English, German, and Portuguese. As Gillett summarises about his work in the field of documentary, “globalization is written into his practice as well as being a theme” (“Documentarist” 320). Via Appia, originally commissioned for television exhibition, had its world premiere at the Max Ophüls Festival in Saarbrücken, Germany, and was later shown at gay and lesbian film festivals in cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and London. On 28 August 1990, it was finally shown on the second channel of German national television. In 1995, it received a video release in the UK, although it has since been deleted from the distributor’s catalogue (Gillett, “Disavowing” 226).

A kind of erotic thriller devoid of desire, Hick’s film follows Frank (Peter Senner), a German flight attendant who, after receiving a positive HIV diagnosis, returns to Brazil to look for the man who deliberately transmitted the virus to him. During his trip, he is accompanied by a film crew, led by Regisseur (Yves Jansen), who records his search in a documentary, and José (Guilherme de Pádua), a Brazilian street hustler who acts as a sort of tour guide across the city’s underbelly. As the slogan on a poster that describes it as “the controversial movie about Brazil’s seedy underworld” teases, Via Appia portrays the clandestine universe of saunas, sex clubs, public cruising, and male prostitution in Brazil through a logic of sexual tourism for foreigners from the Global North. The title references a red-light district in Rio de Janeiro, a hot spot for gay male prostitution during the 1980s.

Subero’s choice to include Via Appia, a European film, to represent Brazil in his corpus, even when the Brazilian Romance (1988) by Sérgio Bianchi had been released a year earlier, and presented a pioneering approach to the representation of the AIDS crisis, points to the fact that Hick’s cult film is one of the main productions that built the image of the AIDS crisis in Brazil in countries of the Global North. Through a film analysis anchored in a transdisciplinary postcolonial perspective, integrating the fields of Cultural Studies, Visual Anthropology, and Media Studies, through the work of Latin American researchers such as Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Néstor Perlongher, and Gustavo Subero, this article aims to reflect on the way in which Via Appia reinforces or challenges tropes of moral panic about hyper-sexualization, violence, and risk in homosexual practices in Brazil. Furthermore, it proposes a queer approach to the notion of otherness present in Brazilian hustlers through the foreign gaze and in the HIV-positive person themselves in relation to their surroundings.

The First Years of the AIDS Crisis in Brazil

In Imagens veladas: aids, imprensa e linguagem (Veiled Images: AIDS, Press, and Language), Rosana de Lima Soares declares that AIDS was marked as a moral disease even before it became deadly (86). Due to its direct association with drug use and sexuality (and male homosexuality more specifically), AIDS was for a long time seen as a rare plague that affected the so-called risk groups. Therefore, the disease quickly became a centre of moral panic in society, the target of fallacious beliefs, myths, and stigmatizations that emerged and were disseminated without any scientific basis. In her analysis of the journalistic coverage of AIDS in Brazil, Soares recognises the role that press discourse played in the construction of imageries about the disease. As queer theorist Richard Miskolci states, AIDS was not just a biological fact but a culturally constructed phenomenon (25). In this sense, it is not only the medical–scientific discourse that is responsible for producing the AIDS device, but also the media narratives. The deliberate choice to categorise the disease as sexually transmitted rather than a viral disease, such as hepatitis, created a strong climate of panic regarding sex that strengthened a moralist movement against the advances of the sexual revolution. Argentinian and naturalised Brazilian anthropologist Néstor Perlongher already in the 1980s denounced the conservative and hygienist approaches that several institutions had imprinted on the disease (O que 70).

The press, however, was not the only media to create and propagate imageries of HIV/AIDS. As Denise Portinari and Simone Wolfgang state, “the influence of the media’s treatment of the issue of HIV/AIDS in the early 1980s was preponderant in the formation of an imagery linked to the disease that still remains present” (50; my trans.). Television, cinema, and other visual media also participated in the process of creating such imagery. Anselmo Peres Alós demonstrates that the urgency of the advent of AIDS culminated in an intense process of discursive creation of the phenomenon. According to the writer, the press, the media, and even literary works reacted and tried to make sense of the newly discovered disease, generating “the first instance of meaning for AIDS” (Alós 3; my trans.). In a description made during the pandemic crisis, Perlongher proclaims that “[t]elevision plays a decisive role in the procedure, which borders on the obscene aspect of spectacularising death” (53; my trans.).

When compared to other countries, including the United States, it can be noted that Brazilian cinema reacted very quickly to the emergence of AIDS. The first HIV/AIDS diagnosis registered in Brazil occurred at the end of 1982, detected by dermatologist Valéria Petri (Perlongher, O que 50). In subsequent years, the disease was treated with indifference, being considered “a fashionable disease” (50; my trans.), a temporary problem that would only affect the affluent gay men population who were able to travel to places like the United States and European countries, where they were believed to have contracted the virus; the common (straight) working man was safe. As reported by Dilene Raimundo do Nascimento, in the early years of the 1980s, AIDS in Brazil ceased to be seen as a “foreign disease”, becoming a “disease of the Other”, due to the fixation at a symbolic level of the relationship between AIDS and homosexuals (88). Perlongher identifies the death of the playwright Roberto Galizia in 1985 as a turning point in the perception of the AIDS crisis in Brazil, starting a new wave of panic on a public scale. Corroborating the fixation denounced by Nascimento, Perlongher outlines that from that year onwards, television started to show images such as “scenes of two gay lads holding hands, and soon after a patient consumed by Kaposi’s sarcoma; panoramic views of gay ghettos, followed by hospital martyrdom” (O que 53; my trans.).

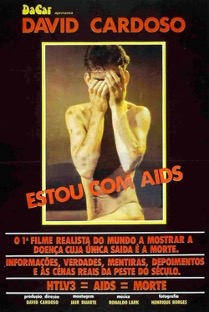

In the same year of Galizia’s death, actor and filmmaker David Cardoso, one of the prime representatives of Brazilian cinema at the time, directed the controversial film Estou com AIDS (I Have Got AIDS, 1985), self-proclaimed on the movie poster as “[t]he world’s first realistic film to show the disease which the only way out is death” (Fig. 1), and which promised to reveal “[i]nformation, truths, lies, testimonies and real scenes from the plague of the century” (my trans.). The film is conceived as a strange hybrid of fictional vignettes and talking-head-style documentary, interviewing public figures and Brazilian celebrities such as the singer Alcione, actor Anselmo Duarte, boxer Maguila, and doctor Valéria Petri herself. Estou com AIDS proposed, in a very sensationalist manner, to fulfil an informative role in relation to AIDS for the greater public. At the opening of the film, we hear Cardoso mentioning in a phone call his aim of realising the project, and saying he can sense an atmosphere of panic around AIDS and that he wants to use cinema as a vehicle to spread information and debunk myths.

Figure 1: The film’s original poster. Estou com AIDS (I Have Got AIDS).

Directed by David Cardoso, DaCar, 1985.

Alongside Cardoso’s work, the directors of Boca do Lixo’s pornographic productions quickly turned their own cameras on the AIDS panic. The films Sexo de todas as formas (All Kinds of Sex, Juan Bajon, 1985), Hospital da corrupção e dos prazeres (Hospital of Corruption and Pleasures, Rajá de Aragão, 1985) and the controversial AIDS, furor do sexo explícito (AIDS, the Furore of Explicit Sex, Fauzi Mansur, 1985), all released in cinemas in the same year as Estou com AIDS, sought to use the explicit sex genre to address issues related to fear and fascination caused by AIDS. As Nuno César Abreu reports, “In 1984, for example, of the 105 national films produced (shown in São Paulo), no less than 69 (without Kabbalistic intention) were sexually explicit” (131; my trans.). In other words, AIDS broke out in Brazil precisely when the production of films with pornographic content was in its most prolific phase, representing the largest portion of national production and public consumption. However, going against the journalistic and television representation of the period, this production focuses mainly (although not exclusively) on the representation of heterosexual characters and sexual practices. All these porn movies acknowledged the risk of death after sex under the threat of AIDS as a morbid arousing quality, eroticizing the fear and panic around the virus as a way to make sense of the tragedy. As Rodrigo Gerace states, drawing a parallel between AIDS, furor do sexo explícito and Via Appia, both films associate “eroticism, paranoia and death” (203; my trans.).In terms of auteur cinema, the first major film to address the theme of AIDS would come a few years later, in 1988. Romance is a feature directed by Sérgio Bianchi and with a screenplay cowritten by Caio Fernando Abreu, an important and prolific Brazilian writer who became one of the first intellectuals to come out as a person living with HIV publicly. Throughout his work, reflections on HIV/AIDS appear frequently, before and after his diagnosis. The film starts with the death of Antônio César, a fictional radical leftist intellectual, and follows the grieving process of three of his friends. Among them is André, a homosexual who preaches the sexual liberation and who may carry the virus. Regarding the AIDS crisis as one of many symptoms of social malady (along with political corruption, ecological disasters, and class inequality), in the context of the post-regime redemocratization of Brazil, Romance presents a quite transgressive, ahead-of-its-time look at representations of HIV/AIDS, not only in Latin America but also worldwide. João Nemi Neto, writing about AIDS, furor do sexo explícito, Romance, and Estou com AIDS, concludes that, while none of them enjoyed a significant box-office success, their filmmakers “captured the early years of AIDS in unconventional and often shocking manners that to this day remain unparalleled in Brazilian cinema” (60).

Contemplating this panorama of Brazilian cinema’s early reactions to the AIDS crisis, with its variety of genres and approaches, it is not difficult to agree with Nemi Neto. Therefore, Subero’s decision to include only Via Appia as a film representing AIDS discourses in Brazil, despite the range of existing productions, points to a possible erasure of these films, in detriment of a history of cinema mediated by the Global North. When approaching the other territories of Latin America, Subero elects to analyse works such as the Argentinian Un año sin amor (A Year without Love, Anahí Berneri, 2005) and the Haitian Le president a-t-il le sida? (Does the President Have AIDS?, Arnold Antonin, 2006), as well as the Cuban soap opera La cara oculta de la luna (The Hidden Face of the Moon, 2007), and the photographic works by Mario Vivado in Chile and Hector Toscano in Argentina. The only other work made by a non–Latin American practitioner is the feature film Before Night Falls (Julian Schnabel, 2000), an adaptation of the autobiographical book by the Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas. Possibly, the author’s selection was motivated by a prior knowledge of Via Appia and a zealous intention of contesting its colonialist representation. However, it could also be a consequence of his lack of acquaintance with the Brazilian audiovisual production. The country is the only one in Latin America to have Portuguese as its native language, which priduces a kind of cultural isolation, and makes the diffusion of Brazilian films in neighbouring countries difficult—especially for works outside the mainstream. Either way, the absence of a Brazilian production in Subero’s selection, and especially its replacement with a European film, is in itself the reinforcement of a colonial gesture.

Crossing the Via Appia

Hick’s experience as a documentarist is not only made manifest in Via Appia by the diegetic presence of a crew filming a documentary within the narrative, but also through the appropriation of documentary linguistic codes. During the development of the plot, the presence of filming equipment is customary, as is the appearance of crew members in the shot and direct interactions between the actors and the camera, breaking the fourth wall. Often, the film’s camera—which operates mostly in a handheld guerrilla style—is confused with the camera that is filming the fictional documentary, assuming Frank’s gaze as the point of view of the narrative. Particularly in the sequences shot on the street, when passers-by interact with and for the camera, it is not possible to say with certainty what is staged and what are spontaneous and real recordings, as everything is filmed with an observational aesthetic in the cinema verité style. This formal choice generates a regime of visibility that places the natives in a position of exposure, as the crew films what they want and how they want, without proposing any negotiation of the representation of those portrayed. Brazilians on the streets are shot with curiosity and detachment, in a dehumanised sense, almost as if on a safari. As all the German characters are played by actors, this discrepancy generates an undeniable power dynamic in the film’s narrative construction.

In Brazil, Via Appia is, to this day, a largely unknown and inaccessible film. Without an official home video distribution on the national territory, Hick’s feature was never released in Brazilian cinemas. It was only as late as 1995 that it received a few showings during the 19th São Paulo International Film Festival. At the turn of the twenty-first century, with a profusion of copies available on online video platforms, the film gained some visibility, especially among gay male audiences and queer cinema aficionados. Currently, the film exists in the public consciousness and is mostly classified as a morbid curiosity in the growing true-crime media scene, due to the involvement of its Brazilian protagonist Guilherme de Pádua in the murder of actress Daniella Perez in 1992, one of the most gruesome and mediatised cases in criminal history in Brazil. During the trial proceedings, Pádua tried to cite the film’s production team as eyewitnesses of his alleged dating relationship with Perez, who played his romantic partner in a television soap opera. Being one of the few audiovisual records of Pádua’s work as an actor, as well as the similarities between his character in Via Appia and accusations he received about his sexuality and involvement in sex work, Hick’s film still arouses the curiosity of some spectators. A complete upload of the film made in July 2022 on YouTube by a user profile titled “Daniella Perez Tribute” has already received more than twenty-two thousand views. But one wonders how many of these viewers actually watched the film in its entirety, after statisfying their curiosity of seeing a murderer years before he committed the crime.

As Gillett acknowledges, Hick’s films have not yet received much scholarly recognition either (“Documentarist” 338). Regarding Via Appia, the author only cites, in addition to his own work, an article written by Astrid-Elke Kurth. After the publication of Gillett’s text, and after Subero’s work, a brief mention of Hick’s film is found in an article by Ángel Jesús Gonzalo Tobajas about the myth of AIDS transmission in urban legends. Despite being written more than a decade ago, Gillett’s postulate remains true. For the purposes of this article, I will focus my discussion on the works of Subero and Gillett, which, presenting diametrically opposed views on Via Appia, allow for a productive comparative exercise.

In his analysis, Subero is resolute in declaring Via Appia as a fundamentally colonialist film from its premise, as “[t]he narrative in the film seems to follow a type of neo-colonialist discourse in which ‘native’ Brazilians are both negatively exoticized and negatively troped by the white ex-colonizer” (4). Gillett, on the other hand, promotes a passionate defence of Hick’s film, arguing that it can be understood as a critique of colonial bigotry. According to him, “Hick’s point, though, is precisely that we must resist the temptation to ‘make sense’ of the syndrome. Because to do so, to extract cultural capital from the problems of a stigmatised minority, is an implicitly colonial practice, like sex tourism” (“Disavowing” 241). Gillett’s assertion echoes the relationship established by the philosopher Eduardo Jardim between the perverse context of the colonial enterprise on the African continent and the advent of AIDS. For Jardim, it was the unhealthy and tyrannical conditions imposed by colonisers on the inhabitants of African colonies that allowed AIDS to spread as an epidemic (15). In this perspective, AIDS as a cultural phenomenon is, from its conception, a colonial aberration.

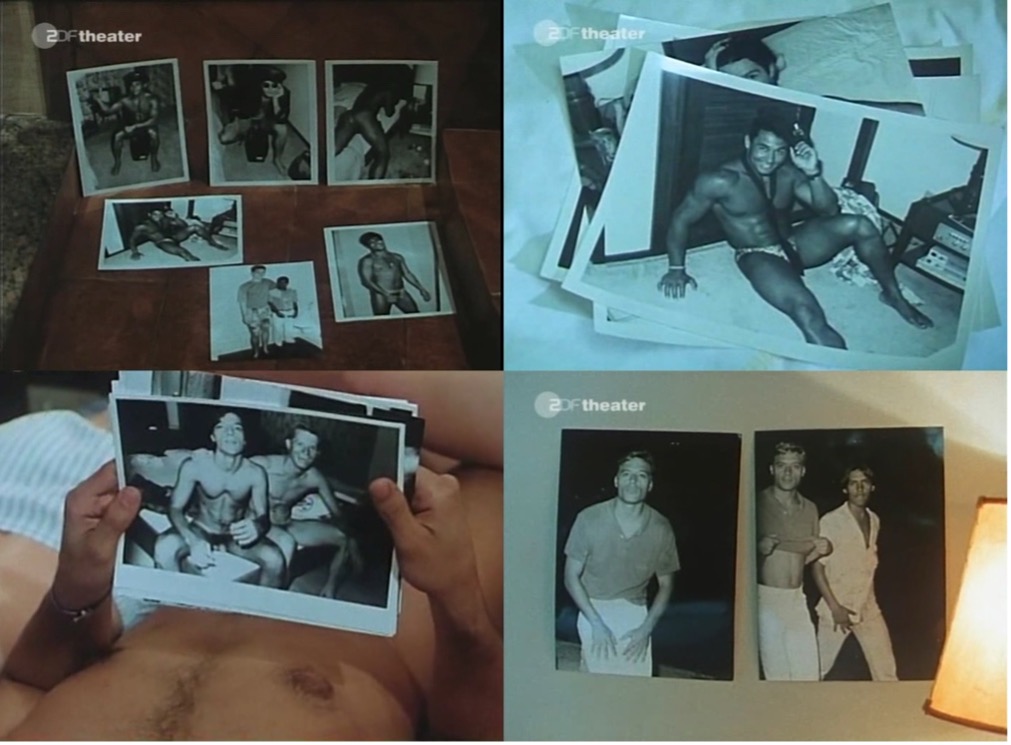

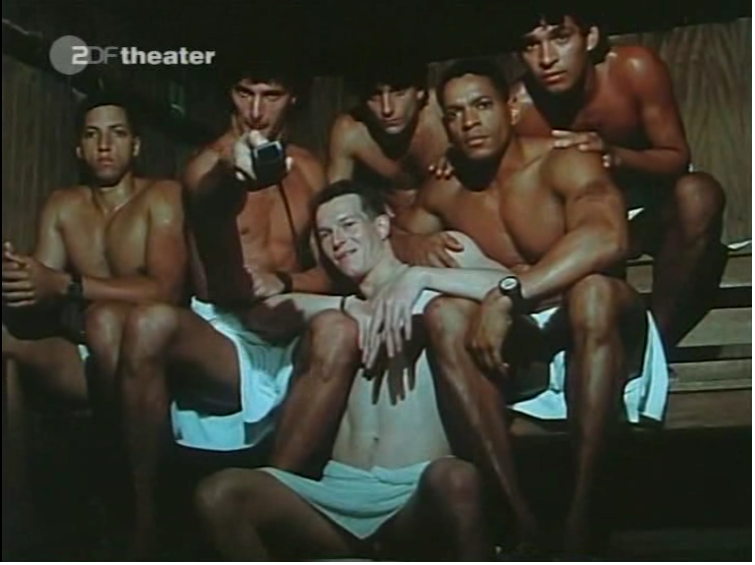

Through Frank’s account, we know that the German man used to go to Rio de Janeiro frequently in search of furtive sexual encounters with the natives. Such behaviour establishes a dynamic with Brazil that inevitably refers to what Anne McClintock called “European porno-tropics” (22). Nelson Maldonado-Torres, in dialogue with the concept coined by McClintock, suggests that such tradition conditions the colonised to a regime in which their bodies are marked “with a particular form of gender difference, that is, oversexualised in the pathological sense of their sexual organs and sexualised parts of the body define their being with or without gender itself” (40). The Brazilian men in Via Appia exist for Frank in a perpetual state of salacious sexual availability, being exclusively defined by their physical attributes (Figs. 2–7). They are always negotiating a programinha (“turning a trick”), offering a helping hand and other body services. In a brief and quite uncomfortable moment, a notably young lad is offered as a sex worker to the men of the film crew while being described by his companion hustler as “Brazilian baby beef”. Frank is, as Subero would argue, unequivocally presented as a sex tourist, albeit a case can be made about Hick’s intention with this representation. As described by Gillett, the quest for Mario is a deliberate critical exploration of otherness. Through the exposure of Frank’s behaviour, and his sense of superiority in relation to Brazilians recognised by Subero, Hick denounces the logic of colonial bodies ready for consumption in porno-tropics tradition, by declaring that

[t]he effect is to underline from a very particular perspective the parallels between colonialism, sex tourism, and the AIDS movie business. The common denominator is an act of exploitation in which a fleeting interest in the discursively pre-prepared exotic and a sexually compensatory pleasure in the exercise of power are necessarily allied to a fundamental disinterest in the actuality of the other and the effects of intervention. (“Disavowing” 239)

Figures 2–7: Brazilian men as bodies ready for consumption. Via Appia. Screenshots.

Despite agreeing with Gillett’s criticism of Frank’s character as a sexual tourist, I think the author failed to notice the way in which Hick’s film demonstrates a lack of interest in the actuality of the other. Except for José, all the other Brazilian men are barely characters; they are portrayed more as props, elements of visual rather than human interest. Although I don’t believe the film reproduces as incontrovertible a colonial vision as postulated by Subero, it is notable how the Brazilians are not given space to exist beyond Frank’s desires. However, I perceive in the interactions between the Brazilians and the power dynamics imposed by Frank and the film itself a series of nuances, frictions, and defiance acts that work against the neocolonial gesture of the narrative, and on which I wish to reflect.

In relation to the argument about sex and power, it is relevant to locate Via Appia in the context of the profusion of erotic thrillers that were being made at the time. There is a consensus in the works of David Andrews, Foster Hirsch, Linda Ruth Williams, and Robert Eberwein that the rise and popularity of the erotic thriller genre during the 1980s are closely related with AIDS anxiety. At a time when sex could in fact mean death, these films presented metaphors about the risks of sexual promiscuity, always maintaining AIDS itself at a safe distance, as “a significant structuring absence” (Hirsch 189). Via Appia subverts the structure established by the genre, conceptualising an erotic thriller in which the anxiety of AIDS and its dangers is no longer allegorical, but turns into a continual and literal presence. The dangers of public sex manifest in the constant news about an American being killed in Via Appia, or in the law enforcement agents who threaten the wellbeing of the hustlers. Even the camera relentlessly violates the anonymous men, who never give explicit consent for being filmed in these marginal spaces, at risk of unwanted exposure. If sexual panic mediated by AIDS permeates the entire narrative, this time it is sex itself that is absent.

Despite taking place in the underworld of sex tourism, with scenes involving everything from masseuses in saunas to street hustlers exposing their erect genitals, Via Appia does not feature any sex scenes. Sexual practices are sublimated and merely indicated by the constant collection of snapshots taken by Frank. As Susan Sontag asserts in her seminal essay, photography has become all at once a form of participation, knowledge, and power, converting the holder of the camera into an active agent and a voyeur: “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed” (174). It is no coincidence that the film’s camera itself often takes the position of Frank’s camera, sharing Frank’s gaze with the viewer. As Subero underlines, Frank “places him in a positional space of white supremacy in which the picture serves as visual evidence of his sexual conquests” (5). In the first interaction between José and Frank, the Brazilian hustler inquires what he is doing in Brazil. “We are making a film about a photographer”, he suggestively answers. Later, Frank says he wants to photograph José in his hotel room, a meeting that only takes place after a financial transaction. The act of photographing becomes a metonymy for sexual intercourse. Often, moments in which a photo is taken in the narrative return later as physical copies of the final image (Figs. 8–11). It is remarkable that the massive volume of photographs taken by Frank become omnipresent trophies in every corner of the film. We see photos hanging on walls, thrown on the floor, placed for development in the bathroom, being admired in the hands of characters. Near the end of the film, a sequence spends a whole minute touring the photographs scattered around the hotel room.

Figures 8–11: Frank taking pictures that later return as physical copies. Via Appia. Screenshots.

Completely disagreeing with Gillett’s statement that the film does not present any trace of promiscuity because we never see Frank having sex with any of his models (“Disavowing” 233), I consider the very materiality of the photographs as elliptical narrative tools to represent the occurrence of sexual activity, without allowing the spectator the gratification of visual pleasure. Some dialogues between José and Frank reveal implicit information about their relationship being also sexual. In an intimate moment in the hotel room, José states, “I don’t have anything”, suggesting he is available for, or even desires, to have sex with Frank. He then goes on to say that, even though he knows that there are people who do not stop having sex because they are “sick”, he does not believe that Frank would be one of them. During his first visit to a sauna in Rio de Janeiro, Frank confesses to us in voiceover, “Why should I say to everyone that I was sick? You don’t live up to what a certain Joe from the sauna says.”

Subero’s remarks about Frank’s photography habits align with Cristopher Pinney’s writing about the rise of colonial travel photography. For Pinney, “[t]he relationship between early photography and European travel is not accidental: the ‘normative’ photograph encoded a practice of photography, which encoded a practice of travel. The ideology of indexicality authorised an autoptic practice of ‘being there’” (204). Frank’s snapshots are not only evidence of an “I was there” but are an act of ownership. More than being there, he wants to take the natives home with him, a subtle dominance gesture (Figs. 12–15). At one point, José asks if he can keep his photograph, to which Frank responds without hesitation with a resounding “no”. To possess an image is a privilege of the coloniser since, as Sontag argues, “As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure” (177). In a particular scene, a close-up registers a recently developed picture of a group of four muscular men on the beach, as Frank’s voiceover says, “Farme de Amoedo, now the beach is called Farme de Amo-AIDS.” Despite being the only character whose HIV status is revealed, Frank constantly treats Brazilian men as potential carriers of the virus, regardless of the fit and healthy appearance of their bodies. Through the freehold of the pictures, Frank not only attempts to control the spaces, but also the narratives about the bodies depicted, at once objects of desire and source of moral panic. Therefore, as Maldonado-Torres summarises, the subjects “that appear below the zone of being generate anxiety and fear, but also desire” (40; my trans.).

Figures 12–15: Frank’s snapshots as sexual trophies. Via Appia. Screenshots.

In addition to the otherness marked in the corporeality and sexual expression of Brazilian natives, there is also a frequent indication of intellectual inferiority. At various times, Brazilian characters are represented as naively believing in myths and misinformation about AIDS. In one scene, José appears surprised and disgusted when he finds a package of condoms. Still, he shows confidence in Frank, saying he knows that in Germany people undergo mandatory tests every six months. At another point, he claims that the Japanese scientists have already discovered a cure for AIDS. In a more documentary-style sequence taken on the streets, a man holds a suitcase with newspaper clippings with headlines such as “AIDS Now Has a Cure”, “Brazil Beats the Plague of the Century”, and “This One Got Better from AIDS” (Figs. 16, 17). Certainly, the film’s representation of popular disinformation in the early years of the AIDS crisis is quite credible. Misperceptions and absurd beliefs about HIV/AIDS still exist to this day. However, what draws attention is the reaction of the German characters when confronted with these behaviours; they content themselves with smiling condescendingly, without ever correcting the information. In a patronising manner, Frank and Regisseur find the misperceptions of noble savages amusing. They, on the other hand, are well-informed, educated European men who would never believe such nonsense.

Figures 16–17: AIDS myths as Brazilian headlines. Via Appia. Screenshots.

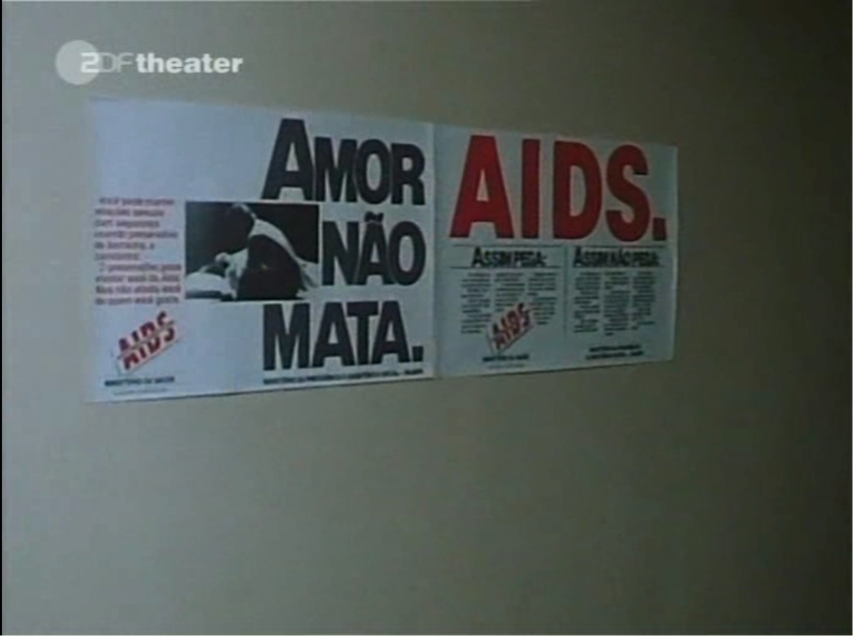

Brazil has been a world reference for HIV/AIDS treatment and care for decades (Portinari and Wolfgang), with a government programme introduced to combat AIDS since President José Sarney’s mandate in 1986, right after the end of the military dictatorship (Jardim 32). Furthermore, from a very early moment, organised civil society activist groups have participated in the fight against AIDS in Brazil. The associations Abia and Grupo pela Vidda, both created in Rio de Janeiro in 1986 and 1989, respectively, carried out pioneering work in the field (Nascimento). Hick’s film, released in 1989, does not indicate a country with such a stance towards the virus. When Frank needs to go to a University Hospital, recommended by his Brazilian colleague, he is informed that only two clinics in the city accept cases like his. As Frank leaves, the camera pauses for a few seconds on an official Brazilian governmental campaign that reads, “Love does not kill” (Fig. 18), as well as on informative tables on the ways of contagion.

Figure 18: Official Brazilian governmental campaign against AIDS. Via Appia. Screenshot.

Reframing Iconographies: Gaëtan Dugas and AnastáciaFor anyone marginally informed about the history of AIDS, the synopsis of Via Appia is suggestive of the mythology of Patient Zero, the first great scapegoat of the AIDS crisis in the Global North. Gaëtan Dugas was a French-Canadian flight attendant who participated in one of the earliest cluster studies in the early 1980s that determined that the virus could be sexually transmitted. As Sara Scott Armengot recounts, Dugas was virulently villainised by the press in the United States, who blamed his promiscuous gay behaviour for the spread of AIDS in the country: “The media invested the story of Patient Zero with a sensational explanatory power: frequently portrayed as a vain serial killer and a monstrous criminal who knowingly spread AIDS from coast to coast, Patient Zero became recognizable as a symbol of gay narcissism, irresponsibility, and culpability” (Armengot 68).

By choosing to tell the story of a flight attendant who contracts the virus in a Third World country, Hick seems to deliberately allude to Patient Zero’s moral panic, amplified by the novel And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts, published just a couple of years earlier, in 1987. Not by chance, Frank himself embarks on a search for the person who transmitted the virus to him, a search to avoid being seen as the ground zero of the disease. That such a search quickly proves to be futile and imperialist (Gillett, “Documentarist” 321) further corroborates the criticism of the archetype of a Patient Zero. Furthermore, Hick’s pioneering sensibility is worthy of recognition, approaching the controversial topic in a swiftly manner even a few years before Zero Patience by John Greyson and the film adaptation of And the Band Played On (Roger Spottiswoode), both from 1993. The allegorical presence of Dugas’s case through his embodiment in Frank draws attention to his own otherness. As Roger Hallas recalls, the discourse of Shilts and the US media constructed Dugas “as an alien sexual other” (164). To some extent, the same can be said of Frank himself. According to Nascimento, if AIDS in Brazil was the disease of the foreigner and became the disease of the Other, Frank, being an avatar of Dugas, concentrates this mark of otherness.

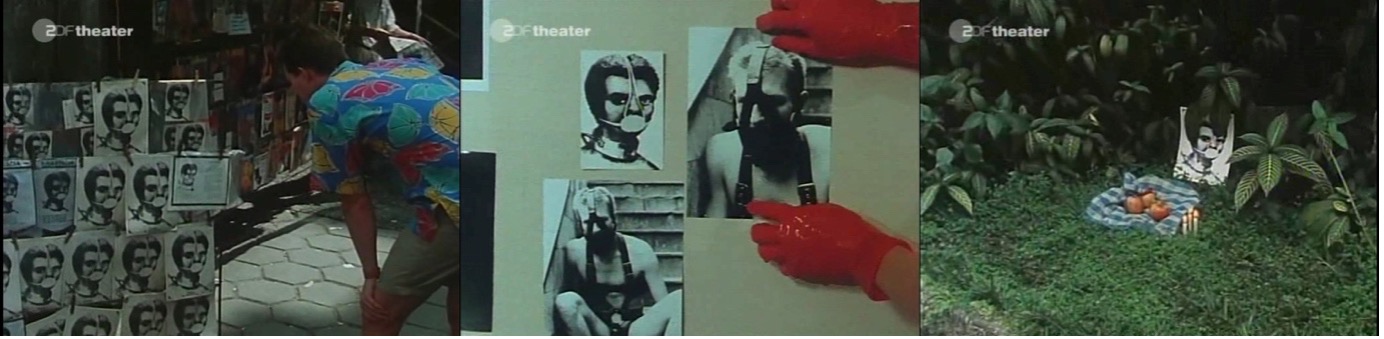

If Dugas’s iconography manifests itself in the film discourse as a symbolic presence through Frank’s embodiment, Hick will evoke Anastácia’s iconography as a literal and recurring presence through her picture. The image of Anastácia, a slave portrayed in an engraving, gagged and wearing an iron collar around her neck, is one of the most heterogeneous symbols of the Black movement in Brazil. Despite her dehumanization and the violence in the way she is represented, Anastácia has become an icon of struggle, faith, and devotion. Her image occupies a singular place between politics and religion, being worshipped as a non-canonised saint by the popular classes while also representing the resistance of the Black population. As Edilson Pereira tells us, there are many versions of Anastácia’s origin myth, which could have ranged from a Yoruba princess to a slave born in the slams of Bahia, Brazil (5). Against her lack of recognition as a saint by the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Catholic Church, Pereira argues that Anastácia’s iconography fits perfectly into the Catholic imagination of martyrdom narratives, since the instruments of slavery torture in her graphic representation acquire a sense of purification: “Under such a framework, the saint’s hagiographies highlight her sexual and racial identity, as an enslaved black woman who became the object of desire and tyranny of the white master” (8; my trans.).

Despite having existed for many decades, the image of the Slave Anastácia earned special visibility around the year 1988, due to the centenary of the Abolition of Slavery in Brazil (Pereira 9). Therefore, her image became widespread in public spaces in Rio de Janeiro precisely during the period in which Hick was filming Via Appia. The presence of images of Anastásia in different places will be a recurring theme throughout the film (Figs. 19–21). Since his arrival in the city, Frank is shown being captivated by Anastácia’s portrait, later being inspired by her image to create a series of self-portraits, in which a fetishist leather mask acts as the gag of the original engraving. As noted by Gillett, “the bitter twists of colonial and post-colonial transference are underlined visually in the film by a complex sequence in which the elaborate gag of the Brazilian slaves is mass reproduced and assimilated to a leather S&M mask worn by Frank himself” (“Disavowing” 232). Later, Frank finds an altar of offerings made by a devotee of Anastácia. José, preventing the German from desecrating the tribute, says that these things are not supposed to be touched. At this moment, the camera faces José frontally, along the lines of a talking-head documentary, in which he recounts Anastácia’s biography as “a special slave, because her parents were very rich people in Africa, so she never accepted to be poor and died for this”. Frank’s fascination with Anastácia, although complicated by dynamics of race, gender, and colonial appropriation, makes sense through his own experience as a person living with HIV. His self-portrait recalls one of the main activist slogans of the period that said “silence = death”.

Figures 19–21: The presence of Anastácia. Via Appia. Screenshots.

Evoking the iconographies of Gaëtan Dugas and Anastácia, Hick illuminates Frank’s own state as the other. Just like Brazilian hustlers, he himself is a body marked by desire and abjection, onto which fantasies of sexual risk and the dangers of gay promiscuity are projected. On this account, he occupies the double position of being the neocoloniser sexual tourist who understands the Brazilians men as otherness, while he himself is the other of the norm as a homosexual and carrier of the HIV virus. Not by chance, in the opening scene, it is Frank who reenacts the role allegedly attributed to Mario. Frank gets out of bed naked after sex, walks to the bathroom and writes on the mirror using red lipstick in capital letters: “Welcome to the AIDS-Club”. In the middle of the film, the scene is repeated in its entirety, but this time lasting for a few more seconds, in which we can hear Frank saying in German “that is all” while looking directly at us through the mirror. In the film discourse, Frank becomes a signifier of the otherness of AIDS projected onto Mario and like Dugas, a symbol of contagion. Like Anastácia, then, he aspires to become an icon of endurance.

Conclusion

Hick’s withholding of closure and a transcendent sense of catharsis is in line with the “queer text” proposal coined by Teresa de Lauretis. According to the author, a queer text is a fiction “that not only works against narrativity, the generic pressure of all narrative toward closure and the fulfilment of meaning, but also pointedly disrupts the referentiality of language and the referentiality of images” (244). Using the axiom “there is no more film” as a quite literal narrative device, Via Appia abruptly interrupts the search for Mario, and the image itself. Going against most AIDS films of the period, which usually conclude with the death of the HIV-positive person, the ending on the beach can be understood as Frank coming to terms with his status as other. Gillett sums up Hick’s subversion well when he says that “[a]ny attempt to construe AIDS as a tragedy entails a failure to come to terms with the senselessness of the syndrome, and is ideologically suspect” (“Documentarist” 322). Throughout the film, the native Brazilian characters frequently work against the narrativity imposed by Frank’s documentary, claiming their agency through small acts of transgression. In the first sequence of photos in the sauna, Frank appears sitting and surrounded by men in a position that, according to Subero, “demonstrates that he regards the natives as lesser human beings” (5). Suddenly, one of them becomes impatient with the delay and takes the remote shutter release from Frank’s hand, while another guy instinctively holds Frank. In a playful manner, he usurps the power of the holder of the gaze, seizing it from Frank (Fig. 22). The scenes shot in the public space of the streets, characterised by a strong documentary aesthetic, are particularly filled with moments like this. In a shot that seems quite spontaneous and realistic, we see a travesti being approached by police officers.[1] Upon noticing the presence of the camera, she rebels saying, “get the fuck out of my face or I’m going to break this shit”, before walking confidently away from the filming. On one of the night trips along the Via Appia, a hustler is filmed refusing to participate in the documentary because he does not want his family to find out what he does. After recounting his motivations, he also deliberately walks out of the scene, leaving an empty frame behind him.

Figure 22: A native takes control of the gaze. Via Appia. Screenshot.

José behaves erratically throughout the entirety of the plot. Guided only by his own interests, he disappears and reappears on Frank’s journey at his convenience. Despite helping Frank in his quest, José shows no loyalty or commitment to his mission. He is, in essence, a Brazilian hustler. Rejecting any desire for domestication and without giving in to Frank’s domination, José never presents himself as a victim. He knows what Frank wants and knows how to manipulate it to his advantage. Therefore, it is José who chooses when to leave the scene definitively. He is the one who can put an end to their porno-tropics dynamics. In complete opposition to the flow of the narrative towards closure, José abruptly and inexplicably runs out of the film, symbolically taking with him a camera stolen from the European crew. At the same time that he endorses the narrative of the dangerous hustler, a distrust and constant threat to foreigners, José becomes an obstacle to the conclusion of the film itself, appropriating Frank’s tool of the gaze and of control as the coloniser/sex tourist/photographer.

Although it is not a representative film of the AIDS crisis in Brazil, Via Appia has more merits than Subero’s analysis gives it credit for. With its provocative approach and critical look at the colonial practices of sex tourism, Hick’s film can offer, as Gillett proposes, a stimulating reflection on the dynamics between colonialism, AIDS, and otherness. The choice of Brazil as a location simply fulfilled the generic function of a scenery recognised worldwide as a paradise for gay sexual tourism, without any ambition to effectively create an accurate picture of the first years of the AIDS epidemic in Brazil. Assessed merely as a European and 1980s production about AIDS, Via Appia provides a genuinely queer and ahead-of-its-time perspective on HIV-positive representation, which remains relevant and even transgressive to this day. In this way, despite not being a realistic record of the AIDS epidemic in Brazil, and leaving much to be desired when compared to its contemporary Brazilian productions such as Romance, the film presents itself as a compelling portrait of the otherness and displacement caused by the moral stigmatisation of people living with HIV, still worthy of being seen and debated by new generations.

Note

[1] Travesti is a gender category present in many Latin American countries, and which predates the emergence of transgender rights in the region. For a long time, the term was used as a mark of marginality, stigmatised and associated with prostitution. At first, the travesti was understood as a type of crossdresser, a homosexual man who performs femininity for sexual excitement. Writing in the mid-1980s, close to the filming of Via Appia, Néstor Perlongher defines that “the attitude of the travesti, and of the effeminate queer in general, would imply a distancing, a rupture with male gestural and behavioural prototypes—indicating a kind of ‘becoming a woman’” (O negócio 20). Currently, many trans people claim the travesti identity as a political gesture, similar to what happens with queer identity in countries in the Global North. According to definitions by Jaqueline Gomes de Jesus, “it is understood, from this perspective, that travestis are people who experience female gender roles, but do not recognise themselves as men or women, but as members of a third gender or a non-gender” (17; my trans.).

References

1. Abreu, Nuno César. Boca do Lixo: cinema e classes populares. Editora Unicamp, 2015.

2. Alós, Anselmo Peres. “Corpo infectado/corpus infectado: AIDS, narrativa e metáforas oportunistas.” Revista Estudos Feministas, vol. 27, no. 3, 2019, pp. 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2019v27n357771.3. Andrews, David. “Sex Is Dangerous, so Satisfy Your Wife: The Softcore Thriller in Its Contexts.” Cinema Journal, vol. 45, no. 3, 2006, pp. 59–89, https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2006.0024.

4. Antonin, Arnold, director. Le president a-t-il le sida? [Does the President Have AIDS?]. Centre Pétion-Bolivar, 2006.

5. Aragão, Rajá de, director. Hospital da corrupção e dos prazeres [Hospital of Corruption and Pleasures]. Danek, 1985.

6. Armengot, Sara Scott. “The Return of Patient Zero: The Male Body and Narratives of National Contagion.” Atenea, vol. 27, no. 2, 2007, pp. 67–79.

7. Bajon, Juan, director. Sexo de todas as formas [All Kinds of Sex]. Galápagos, 1985.

8. Berneri, Anahí, director. Un año sin amor [A Year without Love]. BD Cine, 2005.

9. Bianchi, Sérgio, director. Romance. Embrafilme, 1988.

10. La cara oculta de la luna [The Hidden Face of the Moon]. Created by Freddy Domínguez, Cubavisión, 2005–2006.

11. Cardoso, David, director. Estou com AIDS [I Have Got AIDS]. Dacar, 1985.

12. Eberwein, Robert. “The Erotic Thriller.” Post Script, v. 17, n. 3, 1998, pp. 25–33.

13. Gerace, Rodrigo. Cinema explícito: representações cinematográficas do sexo. Edições Sesc, 2015.

14. Gillett, Robert M. “Disavowing a Deleterious Discourse. Jochen Hick’s Via Appia.” KulturPoetik 5, no. 2, 2005, pp. 225–42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40621740.

15. ——. “A Documentarist at the Limits of Queer: The Films of Jochen Hick.” A Companion to German Cinema, edited by Terri Ginsberg and Andrea Mensch, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012, pp. 318–40.

16. Gonzalo Tobajas, Ángel Jesús. “Mary SIDA y otras agresoras fatales en el folclore internáutico: enfermedad, miedo y mito.” Boletín De Literatura Oral, vol. 5, July 2015, pp. 69–102, https://revistaselectronicas.ujaen.es/index.php/blo/article/view/2181.

17. Greyson, John, director. Zero Patience. Téléfilm Canada, 1993.

18. Hallas, Roger. Reframing Bodies: AIDS, Bearing Witness, and the Queer Moving Archive. Duke UP, 2009, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jfm5.

19. Hick, Jochen, director. Via Appia. Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, 1989.

20. Hirsch, Foster. Detours and Lost Highways. Limelight, 1999.

21. Jardim, Eduardo. A doença e o tempo: aids uma história de todos nós. Bazar do Tempo, 2019.

22. Jesus, Jaqueline Gomes de. Orientações sobre identidade de gênero: conceitos e termos. Edição Independente, 2012.

23. Kurth, Astrid-Elke. “Via Appia: Cruising the Traumatized Self”. Words, Texts, Images. CUTG Proceedings, edited by Katrin Maria Kohl and Ritchie Robertson, Vol. 4, Peter Lang, 2002, pp. 199–14.

24. De Lauretis, Teresa. “Queer Texts, Bad Habits, and the Issue of a Future.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 17, no. 2–3, 2011, pp. 243–63, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-1163391.

25. Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. “Analítica da colonialidade e da decolonialidade: algumas dimensões básicas.” Decolonialidade e pensamento afrodiaspórico, edited by Joaze Bernardino-Costa et al., Autêntica, 2018, pp. 27–53.

26. Mansur, Fauzi. AIDS, furor do sexo explícito [AIDS, the Furore of Explicit Sex]. Virgínia Filmes, 1985.

27. McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Context. Routledge, 1995.

28. Miskolci, Richard. Teoria Queer: um aprendizado pelas diferenças. Autêntica, 2017.

29. Nascimento, Dilene Raimundo do. As Pestes do século XX: tuberculose e Aids no Brasil, uma história comparada. Editora FIOCRUZ, 2005.

30. Nemi Neto, João. Cannibalizing Queer: Brazilian Cinema from 1970 to 2015. Wayne State UP, 2022.

31. Pereira, Edilson. “Da escravidão à liberdade: a imagem de Anastácia entre arte contemporânea, política e religião.” Horizontes Antropológicos, vol. 29, no. 67, 2023, pp. 1–35, https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9983e670410.

32. Perlongher, Néstor. O negócio do michê: prostituição viril em São Paulo. Editora Brasiliense, 1987.

33. ——. O que é AIDS. Editora Brasiliense, 1987.

34. Pinney, Cristopher. “Notes from the Surface of the Image: Photography, Postcolonialism, and Vernacular Modernism.” Photography’s Other Histories, edited by Christopher Pinney and Nicolas Peterson, Duke UP, 2003, pp. 202–20.

35. Portinari, Denise Berruezo, and Simone Marie Berthe Medina Wolfgang. “Imagens e Marcas: Um imaginário ligado à epidemia de HIV-Aids no Brasil.” Revista ALCEU, vol. 17, no. 34, 2017, pp. 45–60, https://doi.org/10.46391/ALCEU.v17.ed34.2017.132.

36. Schnabel, Julian, director. Before Night Falls. El Mar Pictures, 2000.

37. Shilts, Randy. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. Souvenir Press, 2011.

38. Soares, Rosana de Lima. Imagens veladas: aids, imprensa e linguagem. Annablume, 2001.

39. Sontag, Susan. “On Photography.” Communication in History: Technology, Culture, Society, edited by David Crowley and Paul Heyer, Routledge, 2015, pp. 174–78.

40. Spottiswoode, Roger, director. And the Band Played On.HBO Films, 1993.

41. Subero, Gustavo. Representations of HIV/AIDS in Contemporary Hispano-American and Caribbean Culture: cuerpos suiSIDAs. Ashgate, 2014.

42. Williams, Linda Ruth. The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Edinburgh UP, 2005.

Suggested Citation

Marques, Henrique Rodrigues. “Foreign Body: AIDS, Moral Panic, and Otherness in Via Appia (1989).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 25–41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.02

Henrique Rodrigues Marques is a doctoral candidate in the Postgraduate Programme in Multimedia at the Institute of Arts of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), carrying out research on representations and memory of HIV/AIDS in Brazilian cinema. He is a teacher of Communication & Arts courses at São Judas Tadeu University (USJT). In addition to being a researcher, he works as a film critic and curator of film festivals.