Transcending Borders? Observing Lesbian Desire and Intimacy in Ruth Caudeli’s Porque no. (2016) and Petit Mal (2022)

Karol Valderrama-Burgos and Georgia Fielding

[PDF]

Abstract

This article examines the work of Spanish filmmaker Ruth Caudeli by assessing the extent to which her films made in Colombia have contributed to a transnational and feminist perspective on lesbian subjects. By focusing on the short film Porque no. (Just Because., 2016) and the feature Petit Mal (2022), we draw on the concepts of desire and intimacy through a multidisciplinary framework comprising gender perspectives, filmmaking approaches, and Latin American Studies, in order to explore a cinematic mode of representation that reclaims, records, and archives the lived experience of diverse women in the context of Latin America. Significantly, this article brings to light the ways in which Caudeli’s aesthetics exhibit attributes of the melodramatic genre and documentary modes when addressing female same-sex sexuality through cinema. In doing so, the article facilitates the reconceptualisation and critique of the representation of lesbian women through Caudeli’s work, exploring whether it disrupts the heteronormative expectations of the patriarchal societies of Latin America and how non–Latin American filmmakers such as Caudeli have chosen to tackle diversity and women on-screen.

Article

Matters of gender representation and women as sites of visual pleasure have been part of ongoing discussions in visual studies since the late twentieth century (Marshment; Mulvey, “Narrative Cinema”; Gaines; Seiter). This tendency has contributed to shaping how recent generations, informed by the Eurocentric second wave of feminism and sexual liberation movements, have scrutinised women’s place on-screen or behind the camera (De Lauretis; Johnston and Cook; Kleinhans and Lesage; Erens). One may ask, then, to what extent more contemporary cinematic views on women in all their diversity continue to respond to patriarchal perspectives or transcend patterns of counter-representation that were primarily established in the Global North (Kratje; Mdege; White). This turning point highlights how recent approaches to the topic may facilitate encounters between cultures despite their contradictions or geographical limitations. Following Ella Shohat’s advances, it also suggests the importance of problematising further the implications of representing women’s differences with either racially or culturally nonhomogeneous environments (45).

Considering the significance of investigating similar concerns in Global South contexts, such as those of Latin America, and how non–Latin American filmmakers have chosen to tackle diversity and women on-screen, we examine two works made in Colombia by Spanish filmmaker Ruth Caudeli. By focusing on the short film Porque no. (Just Because., 2016) and the feature Petit Mal (2022), this article assesses the extent to which these films contribute to building a transnational and feminist perspective on lesbian subjects and evaluates the new directions for the concept of the gaze. While diverging from each other in format, we suggest that her 2016 short and her 2022 feature coincide in exploring lesbian women’s experiences and the private spaces they inhabit as part of a larger visual strategy that Caudeli implements to advance perspectives on lesbian and cuir desire and intimacy.[1] Studying Porque no.—a filmthat depicts the complexity of an erotic relationship between two women—we investigate how melodrama is used to construct an on-screen representation of lesbian desire and to disrupt the heteronormative expectations of a patriarchal Colombian society that has traditionally prioritised men’s pleasure (Ponce de León 344; Valderrama-Burgos, Mujer 214).Then, analysing Petit Mal—a film that showcases a polyamorous relationship between three lesbian women—we investigate the strategies used to develop an intimate tone around gender diversity, as well as a reflexive approximation of cuir existence through an unprecedented figure in Colombian films: a throuple of women. Likewise, this article brings to light how the filmmaker’s aesthetics exhibit attributes of the melodramatic genre and documentary modes when addressing female same-sex sexuality through cinema.[2] Below, we first draw on the cinematic modes of melodrama and documentary, informed by the work of Thomas Elsaesser and Bill Nichols, respectively. We subsequently articulate the concepts of desire and intimacy to explore Caudeli’s cinematic mode of representation which reclaims, records, and archives the lived experience of diverse women in the context of Latin America.

Defining desire is difficult due to its subjective and personal nature. As a foundation, sexual desire can be “a longing for something that we do not currently have”, a “need to connect intimately with others”, or an indicator of wishing to have sex (Levine 41). Amy Villarejo indicates that desire is a propulsive force which “[remains] elusive, unpredictable and capricious.” (18). As a result of its elusiveness, lesbian desire cannot be depicted “easily or accurately” (Villarejo 18). In this article, we therefore view the depiction of sexual activities expressed by at least two women for one another to be one of several (physical) manifestations of lesbian sexual desire, without acknowledging a single definite value. Given its “numerous subtleties”, we address lesbian desire as a fluid, personal experience that exists outside heteronormativity, recognising there are varied ways to enjoy pleasure and sexual attraction (Levine 40). As for intimacy, the article embraces the interest placed in how women’s “poder[es] secreto[s]”[3] —secret powers and skills—prevail and voice forms of resistance (Roffé qtd. in Tierney-Tello 284). Thus, we address intimacy as the possibility to reappropriate female existence through narratives that probe power relations and internal conflicts, that unveil personal symptoms of a historically social invalidation, and that self-affirm diverse personal and nonlinear experiences (Mourenza; Martin; Tierney-Tello). In sum, this article offers feminist alternatives to desire and intimacy, allowing the reconceptualisation and critique of the representation of lesbian pleasures in Caudeli’s work. Importantly, following Will Higbee and Song Hwee Lim’s critical revision, we conclude by interrogating the extent to which Caudeli’s films qualify as transnational work (9–11). Thus, this article considers how such an oeuvre, made in Colombia by a Spanish-born woman, can “bring into question the fixity of national cultural discourses” by offering a liminal, liberating, and influential visual style, all at once (Higbee and Lim 11).

Caudeli: Transnational and Feminist

Caudeli, a Spanish-born woman who lived for a ten-year period in Colombia until 2023, is among the best-known and few prolific women filmmakers in the twenty-first-century Colombian cinema industry. Caudeli first studied audiovisual communication at Universidad Politécnica de Valencia before completing a master’s degree in film directing at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and her first short film: Tarde (Late, 2010). Her portfolio expanded with productions made in Colombia, comprising a total of five short films, four web series, four feature films, and several video clips. In Colombia, Caudeli established herself both as a university tutor in the field and as a renowned practitioner using a Colombian context as the backdrop to her films, while always working with Colombian film crews. Using local crews allowed her productions to officially receive the National Product Certification issued by Dirección de Audiovisuales, Cine y Medios Interactivos (Directorate for Audiovisual Media, Film and Interactive Media), Ministry of Culture of Colombia (Santamaría).[4] Nonetheless, her audiovisual work has shaped a foundational transnational body of storytelling wherein alternative forms of life narrative unfold, moving away from dominant heteronormative threads that have pervaded Latin American cinema. As Gema Pérez-Sánchez asserts when analysing hybrid and cuir “storyspaces” in a Spanish context, we argue that Caudeli’s work made in Colombia also offers “new notions of the self and new demands” (167). Her approach goes beyond national concerns and instead “emerge[s] from transnational flows of information, theory, histories of activism, and personal contacts” (Pérez-Sánchez 176). As discussed below, Caudeli’s films showcase how issues relating to women’s sexuality and diversity are no longer marginalised within the heteropatriarchal contexts of Spain and Latin America. Today, Caudeli’s films allow us to understand how the (new) cinemas of Spanish-speaking contexts emerge and circulate with a certain limitlessness to celebrate approaches to lesbian filmmaking (Alvaray 67; Durovicová ix–x; Newman 4).

Caudeli uses her camera as a feminist tool to interrogate patriarchy and gender, always focusing on how life and relations can develop nonnormatively. Her work usually centres on events informed by her own life experience in collaboration with her real-life partner Silvia Santamaría for the creation, production, and release of earlier pieces like Porque no.[5] Likewise, Caudeli has acknowledged the polyamorous throuple relationship she has with Santamaría and Ana María Otálora, which later becomes the leitmotif for the film Petit Mal (Berger). As can be seen throughout Caudeli’s oeuvre, her material highlights cuir women as protagonists and creators of each story and displays a narrative strategy by focusing on “creative anecdotes” (Lipton and Mackinlay 41). That is, “the material, emotional and affective dimensions of social experience” that Caudeli prioritises enable the crafting of a passionate feminist practice, in which the woman’s self “break[s] the constraints of the masculine tradition” (Lipton and Mackinlay 39–40). In the context of Latin America, this approach has developed new avenues of narration where women have historically had little space for expression (Rueda 75). Caudeli builds in-between spaces of existence that transcend binaries and take shape in her diaspora in Colombia. Consequently, the discourses proposed describe intimate events through “self-reflective narratives broadly situated within the fields of auto/ethnographies [because t]hey capture the mundane everyday as well as documenting something out of the ordinary and unusual” (Lipton and Mackinlay 41). This practice echoes the premises of both feminist projects she has led with Santamaría and Otálora: Ovella Blava Films, the production company that Caudeli cofounded whilst residing in Colombia and Set de Cinema: Estudi Actoral Valencia (Cinema Set: Valencia Drama School), which they have been coleading since April 2024.[6] Through the first-hand accounts Caudeli chooses to develop, a shared authorship and agency flourishes in concert with an emancipatory process within the practice of filmmaking that transcends its aesthetic efforts (Seguí 83). Thus, her portfolio attests to how traditional forms of narration and relevant aspects for the self—such as desire or intimacy—become focal points to reclaim, record, and archive modalities of love, pain, climax, or loss through lesbian subjects and through different voices (or gazes).

The Melodramatic Mode

While the definition of melodrama usually refers to a myriad of subcategories that emerge from this genre, Elsaesser proposes that “everybody has some idea of what is meant by ‘melodramatic’” (433). Melodrama is widely known for displays of heightened emotions, whether it be crying, laughter, anger, or the expression/repression of sexual desire (López 444; Mercer and Shingler 1; Williams, “Melodrama” 46). Elsaesser acknowledges these connotations of the term “melodramatic”, saying the mode is characterised by an “exaggerated rise-and-fall pattern in human actions and emotional responses” within the film’s plot (443). Melodrama is thus marked by “a quicker swing from one extreme to the other than is considered natural” and a preference for “intensity” (Elsaesser 443). Subsequently, melodrama manifests as a rise in emotion which is then followed by unexpectedly dropping this emotion “down with a thump” (453). In doing so, the melodramatic mode has usually focused on the desire for “unattainable goals”, depicting characters trapped in a perpetual cycle of unfulfillment (457). Based on Elsaesser’s identification of key characteristics of melodrama, it can therefore be defined here as a narrative approach that gives precedence to elevated emotions by means of “lighting, montage, visual rhythm, decor, style of acting, [and] music” to communicate the suffering of characters because of desires made unobtainable by a particular society (446).

Hugo Chaparro Valderrama reveals that melodrama was introduced to Colombia by the Italian Di Domenico brothers and their contentious 1915 film, El drama del 15 de octubre (The Drama of 15 October), the first feature film made in Colombia, which reconstructed the assassination of the Colombian liberal politician and military leader, Rafael Uribe Uribe (33).[7] Consistent with what was taking place in other countries in the region (López 443), the Di Domenico brothers used melodrama and documentary reenactment to parallel patriotic and sentimental fears of early twentieth-century Colombia, ranging from fear of social change, class inequalities, and gender roles, to anxieties surrounding cinema itself as an emerging art form (Chaparro Valderrama 33). Against this backdrop, it is no surprise that Colombian films of the time contributed to establishing female imaginaries based upon moral codes, hypersensuality, excessive use of make-up, and garments that highlighted physical appearance, the female body or standardised ideas about women’s attractiveness (Chaparro Valderrama 34). The hypersexualised and melodramatic role women played from the early years of Colombian cinema, and more broadly, paved the way for gendered representational codes and reflected what feminist film theory would later criticise trenchantly from the 1970s until today.

Discussing the relationship between women and melodrama in mainstream films, Kathleen Rowe states that the genre has “reinforced feminist film theory’s ambivalent but close relation to psychoanalysis, an interpretive paradigm that (despite its many variations) ties femininity to castration, pathology, and an exclusion from the symbolic” (41). It can thus be argued that melodrama relies on the male gaze as a form of commodification, positioning women in an “exhibitionist role” in which they are “simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact” (Mulvey, “Narrative Cinema” 11). Even when melodrama screens a seemingly transgressive woman, one with agency and voice, it paradoxically allows her “to triumph only in her suffering” (Rowe 41). Hence transgressions of the patriarchal expectations that place the female body as an object of the male gaze can only be achieved through women’s pain, frustration, or loss. From a feminist stance, melodrama critically examines the role of women within patriarchy and the “contradiction[s] between oppression and subversion” of women characters; only then can we “begin to build art forms that are less repressive to women” (Kaplan 47).

Melodrama and Lesbian Desire in Porque no.

Porque no. is a short film released in Colombia in 2016. With a running time of thirteen minutes, the plot is seemingly uncomplicated, revolving around a car journey shared between two friends, Paula (Luna Baxter) and Victoria (Silvia Santamaría). The main turning point occurs when they stop at the side of a secluded road in rural Colombia. Although the plot develops over the course of the car journey, the filmexplores the tensions that exist between the protagonists as they express their unhappiness with one another. Using Elsaesser’s conventions of melodrama, Porque no. records Paula and Victoria traversing the unclear boundaries they experience between a platonic and romantic relationship. Founded on a feminist approach informed by Mulvey, Kaplan, and Rowe, the following paragraphs analyse whether melodrama reinforces or transcends heteropatriarchal expectations of lesbian women’s sexuality that depends on the pleasure of men. We accordingly focus on how, in the Colombian context, the melodramatic genre in Porque no. addresses conflicting layers of apparent heterosexual female sexual agency and cuir sexual agency as identified by Mulvey and Rowe.

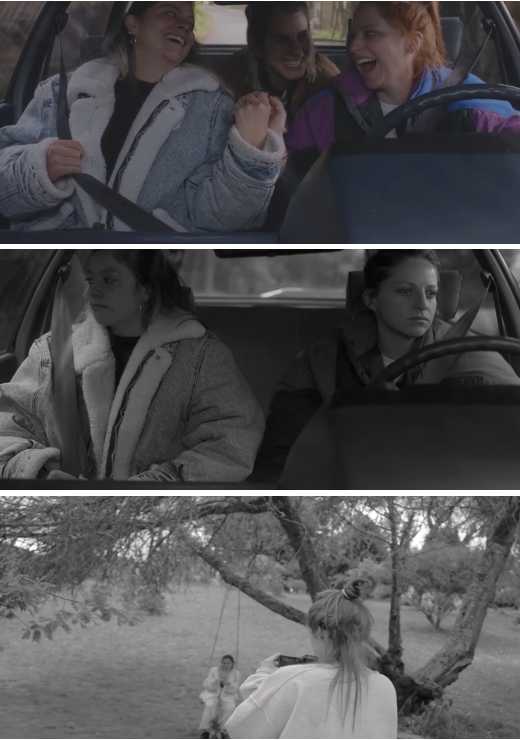

Porque no. employs melodrama to screen how the relationship between Paula and Victoria fluctuates in response to their sexual desire. Nonetheless, Caudeli disrupts the expected characteristics of this cinematic mode. While Mary Ann Doane has analysed the role of interior spaces in melodrama, stating that it “becomes the analogue of the human body” (288), Elsaesser builds on this, explaining how melodrama often happens inside the home, symbolising claustrophobic atmospheres (455). Notably, however, the action in Porque no. occurs outside. The argument between the two women and their sexual encounter take place at the side of the road, in public. Although they are in a peripheral location, by stepping out of the car, they nonetheless move their intimate and private interactions into the public domain. Even though they are not discovered by passers-by, the risk remains, evidenced when a car drives past and interrupts their kissing (Fig. 1). As the two women stop kissing, concerned about being caught, Caudeli critiques how cuir relationships often exist on the margins of a heteropatriarchal society, and that lesbian desire, in particular, lacks visibility. The angled camera, directed over the shoulder of Paula, also indicates the instability and vulnerability of their cuir relationship. By setting the short film outside, Caudeli transgresses the expected structure of melodrama by providing her characters with an open space that has potential, unlike the “claustrophobic” home settings often seen in melodrama and associated with domesticity or stereotypical women’s roles (Elsaesser 455). Interestingly, Caudeli employs techniques Elsaesser identifies in the melodramatic mode to address both women’s desires. There is the depiction of intense and rising emotion, through shouting, name-calling, and arguments about past choices (Fig. 2), and, later, an impassioned sexual encounter (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the camera movement and hand-held camera create a “visual rhythm” that hyperbolises their emotions (Elsaesser 446). Editing techniques, such as moving from wide shots to close-up camera angles, allow us to focus on their angry or lustful facial expressions. Explicit and inflated displays of female emotion throughout the film contribute to a critical or unfavourable impression of female desire. Nevertheless, Caudeli’s use of the melodramatic mode in Porque no. to communicate lesbian desire ultimately offers space for alternative interpretations of how melodrama manages to depict woman’s sexual agency.

Figures 1–3: A car goes past just after Paula and Victoria have kissed on the side of the road (top). Then, they confront each other in a heated argument due to a homoerotic experience they once shared (middle). Soon afterward, the close-up shot captures their lesbian desire after arguing (bottom).

Porque no. (Just Because.). Directed by Ruth Caudeli, Ovella Blava Films, 2016. Screenshots.

Mulvey states that melodrama is “actually, overtly, about sexuality” (Visual and Other Pleasures 35). Williams agrees by labelling melodrama as a “body genre”, defined as a genre “whose non-linear spectacles have centred more directly upon the gross display of the human body” (“Film Bodies” 3). In tandem with Elsaesser, Williams describes melodramatic films as excessive, owing to “their gender- and sex-linked pathos [and] for their naked displays of emotion” (“Film Bodies” 3). Such explicitness is established through “the spectacle of a body caught in the grip of intense sensation” (4). The scenes of sexual intimacy between the two women in Porque no. might support Williams’s claims, which could themselves be seen as problematic. Ruth Harris contextualises the excessive display of emotion on-screen by explaining how up until the 1980s, “the exaggerated emotional state of women was an important feature of a view which regarded them as hysterical” (48). Bringing to light how hysteria was historically linked to criminality, Harris claims that women who did express intense emotion were deemed “both mentally unstable and socially dangerous” (50). Accordingly, the melodramatic, hysterical emotions in Porque no. should, in theory, be detrimental to the representation of women. Upon closer analysis, however, it can be argued that the melodramatic mode enables Caudeli to depict women who reclaim the term hysteria, as will be discussed below, transgressing the patriarchal norm that restricts, diminishes, and mistreats women’s emotional and sexual needs.As they drive to a wedding, Paula and Victoria engage in a heated argument about a kiss which had previously occurred between them, although the kiss itself is not shown in the film. Caudeli tracks and parallels the characters’ own movements as they argue through a handheld technique which triggers an immersive experience for the audience (Cavendish 7). As their argument builds and shouts increase, the camera movement becomes more pronounced, dizzily mirroring their erratic hand gestures and their back-and-forth pacing. Seemingly overcome by intense sensations, Paula pushes Victoria so that she is outside of the camera frame, highlighting the rash and impulsive nature of Paula’s action. Laura U. Marks discusses the theory of haptic visuality in which haptic images—characterised by blurred focus, extreme close-ups, and attention to sensory detail—are used “to bring the image closer to the body and the other senses” (152). Instead of the audience exclusively identifying with the characters, haptic images bring us closer toexperiencing events that are “encoded only by the body” (130). Paula’s action, as well as Caudeli’s use of this dynamic shot to frame the argument between Paula and Victoria, triggers a bodily response in the viewer, mirroring the abrupt and unexpected nature of the push and intensifying personal and tactile memories. Eliciting a heightened effect and affect, this has the potential to resemble events lived by the audience themselves.

A similar handheld camera technique is employed during the subsequent sexual interaction. After Paula loudly confesses that she liked the kiss which had previously occurred between them, Victoria kisses her. Paula’s revelation enables them to satisfy their desire for one another, even if only temporarily. As they kiss, the camera jolts back and forth, “add[ing] immediacy, energy, tension and urgency to the film” (Dadar 233). It manifests the intense flood of eroticism the women are experiencing and, in addition, succeeds in emphasising the emotional instability of both Paula and Victoria. Echoing Dadar’s point, the camera creates a shaky effect of “sensorial disorientation”, haptically communicating to the audience the urges and bewilderment of the women (233). The extreme close-up and unsettling camera angle simultaneously provide spectators with intimate details of the two women kissing (Fig. 4). While this technique might commodify women’s bodies, we propose that Caudeli’s haptic depiction of their sexual encounter, instead appeals to a different, perhaps cuir gaze. Caudeli uses and disrupts the accepted norm of melodrama that positions the woman as the centre to appeal to the male gaze. Not only does she provide representation to an underrepresented community and event, but she also explicitly addresses the complexities they face.

Figure 4: An extreme close-up and canted angle emphasise an intimate view of Paula and Victoria’s intense encounter. Porque no. Ovella Blava Films, 2016. Screenshot.

The charged encounter, indeed, could lead Paula and Victoria to be described as hysterical. The hysterical woman on-screen “cannot self-discipline or self-regulate” her emotions (Rowe 61), and has historically been considered unable to satisfy sexual desires (Ellis 602). In Porque no., the term hysterical can be applied to both Paula and Victoria as the camera motion draws attention to their neglected desires and “unregulated” emotions such as shouting and physical aggression, or their rushed sexual interaction outside the car (Fig. 5). Revising the image of hysterical women on-screen, Kristyn Gorton explains that “hysteria continues to be used as a metaphor or expression of repressed or inarticulate [women’s] desire within popular culture” (45). She further states that the hysterical woman is “one who is ignoring her sexual instincts” (62). Building on this, Caudeli’s melodramatic depiction of female emotion can therefore allude to the sexual repression experienced by women as a consequence of a society and industry that have prioritised men’s heterosexual desires. In doing so, Caudeli brings to the forefront of the audience’s minds the restrictions that patriarchy places on any female sexual desire, namely, emotional instability, sexual repression and dissatisfaction. Notwithstanding these constraints, as Chaparro Valderrama remarks, melodrama can also encourage self-reflection (33). Caudeli therefore uses melodrama to prompt us to contemplate how Colombian society responds to women, cuir women in particular.

Figure 5: The way this erotic interaction occurs suggests the women’s desire is pressing and subversive.

Porque no. Ovella Blava Films, 2016. Screenshot.

The change in camera angle after this erotic interaction highlights further patriarchal transgression. Continuing with the handheld technique, the camera steadies and zooms out to a wide shot as Paula and Victoria’s sexual encounter ends. Contrasting with previous close-up shots used, the wide shot diminishes the sexual and emotional tension. The relative stabilisation of the camera dampens the sense of urgency previously established and reduces the effect of sensorial disorientation, suggesting emotional tranquillity which was absent before (Dadar 233). Further proof of this shift is the protagonists’ silence and lack of conversation, reinforcing Elsaesser’s previously mentioned point on rising emotions being suddenly dropped. The contrast between the successive close-ups and wide shots implies a shift in perspective in how the women view themselves and each other after their intimate sexual interaction, and therefore suggests an acceptance—albeit temporary—of their same-sex desire for one another.

With female sexuality addressed in Porque no., it is pertinent to consider this sexuality in the context of cuir melodrama. What distinguishes cuir melodrama from mainstream melodrama is the inclusion of the coming out arc, used to discern the cuir identity of the protagonists. Cora Butcher-Spellman discussing queer melodrama and the coming-out procedure, defines this subgenre as “melodrama by, for, and/or about queer people” with the central purposes of “storytelling, disruption, and critique” (1). Butcher-Spellman explains that not only is coming out often performed using melodrama but it also “becomes a simplified, one-time event and destination rather than a repetitive process or highly contextual collection of experiences” (4). Hence, the melodramatic portrayal of a character’s realisation and revelation of their sexual orientation often underpins the coming-out experience. Problematically, Gilad Padva suggests that “the melodramatic form of [melodramatic queer films] does not confront adequately the difficulties of coming out, often treating coming out as medicinal, or at least, better than not coming out, and thus romanticizing an overly dichotomized choice” (358). Both scholars acknowledge how exposing a character as queer in a melodramatic context inadequately represents the coming-out experience. Although Caudeli’s Porque no. does use melodrama to portray part of the coming-out process, we argue that it disrupts a “romanticising” and “simplifying” narrative by unveiling the intricacies and difficulties women face when coming out in heteropatriarchal societies.

Initially, the women in Porque no. are presented as heterosexual as Paula talks about a man she is dating while also revealing that Victoria has had sex with several men. However, when hypothetically discussing the possibility of being a lesbian, Paula rhetorically poses the question “¿Qué pensarían?” (“What would they think?”), showing preoccupation with her parents’ reaction if she revealed her lesbian sexuality to them. In response, Paula gradually verbalises her stereotyped view of lesbians. In a derogatory tone, she proclaims that she would be labelled “la arepera de Bogotá” (“the lesbian of Bogotá”), indicating that her concern extends to how her cuir sexuality would be perceived negatively within Colombian society.[8] She subsequently discloses her fear of having to wear checked flannel shirts or walk hunched over like a man. With the deontic modality “tengo que” (“I have to”) expressing obligation and necessity, there are life events Paula feels bound to accomplish. Idealised patriarchal milestones—such as marrying a good husband or having children—would be jeopardised by coming out. Paula’s overall judgement that lesbianism “es asqueroso” (“is disgusting”) and “raro” (“strange”) summarises the anxieties disseminated to her by patriarchy which instructs that homosexuality is unnatural, systematically punishing it through these misconceptions. During the climax of their argument, Paula temporarily overcomes these anxieties surrounding her sexuality. Shouting at Victoria, she admits she has not been able to stop thinking about the kiss they had previously shared, a confession which gives the women permission to satisfy their desire for one another. However, given the nature of the ending of Porque no.—in which Paula resumes talking about the men she wants to date—this permission is not permanent and seems instead dependent on the peripheral location in which their sexual encounter takes place.

The ending, rather than depicting the women as being “healed” by the “medicinal” process of coming out, returns them to a state of “normality”, defined in this case as a return to heterosexuality (Butcher-Spellman 358) and the melodramatic loop of unattainable goals (Elsaesser 457). As the two women drive away in the exact same discursive and visual manner in which the film started, the cyclical structure signals that the realisation of their cuir sexuality and potential coming out has not altered either woman’s immediate present or future. In contrast to Butcher-Spellman’s statement on melodramatic coming out scenes being a one-time event, the earlier kiss between Victoria and Paula and their sexual interaction within the short shows their coming out to be a collection of dispersed incidents instead. As a wedding marks the end of this journey, heteronormativity becomes their ultimate destination. Porque no. provides further critique of the cuir melodramatic mode as the coming out of both women relies upon their sexual interaction, namely, neither Paula nor Victoria explicitly recognise themselves as lesbian, bisexual, or cuir. Without simplifying the revelation of their homosexual desire, Caudeli demonstrates that coming out, or exploring diverse sexuality, is not as candid as assigning a label to oneself. Porque no. employs melodrama as a provocative tool regarding stereotypes and societal perceptions of lesbianism and female same-sex desire, displaying Paula and Victoria’s sexuality as somehow fluid. The sexually intimate encounter in Porque no. provides an unconventional interpretation of the coming-out storyline that simultaneously critiques heteronormative society by challenging how exactly lesbian and cuir woman are defined under patriarchy and bringing to light restrictions placed on female desire.

Intimacy and Documentary in Petit Mal

As noted above, Caudeli’s Porque no. was an early declaration of patriarchal transgression in her overall oeuvre, using camera angles and movement as relevant techniques to question and intensify women’s desires. At the same time, the short film exposes a key interaction between the director and its two protagonists, suggestive of both the love triangle and documentary traditions that would later and explicitly manifest in her feature Petit Mal. Bills Nichols and Michael Chanan agree on how documentary is a type of filmmaking that cannot be easily defined despite conceptualisations that comprise truthfulness of realities, or peoples and the real world on-screen—often led by the social or political (Nichols 10; Chanan 22). Here, we consider what Nichols proposes in his Introduction to Documentary, and what María Luisa Ortega echoes in the context of Latin America. Hence our starting point is to recognise how documentary filmmaking becomes a stylistic choice that enables filmmakers such as Caudeli to “speak to power rather than embrace it” (Nichols 4) and, therefore, to revolutionise the supremacy of the informative gaze by giving way to “the modulation of polyphonous voices and testimonies” (Ortega 51, our trans.). Nichols is right when affirming that while definitions such as the above may be helpful to discuss the meaning of this mode of filmmaking, they also bring notable flaws with them since: “[d]ocumentaries adopt no fixed inventory of techniques, address no one set of issues, display no single set of forms or styles. Alternative approaches are constantly attempted, then adopted or abandoned. [...] They push the limits and sometimes change them” (Nichols 11).

In the context of Latin America and Colombia in particular, documentaries have been a longstanding practice that dates to the 1910s as well as to the Di Domenico brothers’ work, flourishing between the 1960s and the 1970s with the rise of the New Latin American Cinema (NLAC) movement (King 12–26; Ortega and Martín Morán 42; Rivera Betancur, “Research” 32). As extensively discussed, filmmaking of this period excelled by exploring ideals of human liberation, denunciation, and people’s political awareness, gradually building a revolutionary project. Colombian filmmakers including Marta Rodríguez, Jorge Silva, Carlos Álvarez and Gabriela Samper—among others—are emblematic of these efforts made at a national level to denounce social inequality through documentary stylistic choices (Rivera Betancur, “El papel” 50; Valderrama-Burgos, “Mujer” 20–23). Instead of replicating authoritative voices or gazes behind the camera, their trailblazing work was characterised by the shared concern of exploring the marginal and the “hidden” societal peripheries by giving agency to the oppressed. Similar to what Porque no. shows with melodrama, and as Petit Mal evinces, documentary filmmaking techniques help consolidate alternative standpoints and modes of production to redefine larger genres.

Nichols and Ortega have thoroughly investigated how representation in documentaries involve particular strategies. Nichols outlines six modes: the poetic (the more experimental style); the expository (the most traditional mode where voiceover and evidentiary editing prevail); the observational (whose interest is unobtrusive and placed on the subjects); the participatory (where interactions between filmmakers and subjects are central); the reflexive (the style through which audiences are aware of how the medium addresses reality); and the performative (the most subjective and expressive mode where filmmakers and audiences become involved with the subjects) (Nichols 22).[9] Additionally, Ortega explores four strategies through which Latin American documentary traditions have been (re)defined: the counter-informative nature of the works; the way(s) in which the films often impact the audience, so spectators can consciously play a more active role; the capacity of documentary filmmaking to encourage social and political transformation; and the role these films plays for the audience to deconstruct social realities or documentary traditions on deep levels (Ortega 48–49). Both scholars warn us on how these strands of documentary production are neither rigid nor stalled. As they observe, these tendencies often intertwine and cross-influence their goals and effects (Ortega 49), eventually producing pieces “of a more hybrid nature” as is the case of Petit Mal (Nichols 22).

Petit Mal is the fourth feature made by Caudeli. Shot under COVID-19 restrictions and premiered at the 2022 Tribeca Festival, this film sits comfortably in the docufiction category. While it is not a documentary, the film resorts to and adapts modes of documentary filmmaking to fictionalise the director’s lived experience. Petit Mal blends observation, participation, and reflexivity as stylistic approaches within the storyline, and, additionally, it gives the concept of the gaze a new direction (Valderrama-Burgos, “Intersexuality” 156–57). The film is based on an episode in Caudeli’s life, which she and Otálora underwent together, while Santamaría was away from home. Through five chapters, the film chronicles what Anto (Ana María Otálora), Martina (Silvia Santamaría), and Laia (Ruth Caudeli) experience as the leading throuple within the story. The film navigates fictionalised events in their own real-life polyamorous relationship, concentrating on Anto and Martina’s experience when Laia is temporarily absent due to work commitments abroad.

The following paragraphs explore how Petit Mal privileges the unprecedented figure of the female throuple in Colombian cinema and forms of intimacy, contemplation, and transformation on the part of the protagonists. The analysis below also offers insights into how this film epitomises a wider political thread in Caudeli’s career that does not belong to an exclusive genre, territory, or context “in which the overall main purpose is representing women who do not fit the heteropatriarchal mould” (Valderrama-Burgos, “Diversity” 116). This tendency closely aligns with a key feminist tradition: the autobiographical and self-referential practice whereby women’s voices are gathered and prioritised “in constructing the narratives of their own experiences”, acknowledging “the pleasures, challenges, contradictions, and negotiations that these women experience when they speak in a feminist language” (Lipton and Mackinlay 16). Mirroring the foundational and aesthetic dimensions of documentary filmmaking in Latin America (Ortega), yet through a fictionalised and feminist approach, Caudeli resignifies the context addressed and re-envisions discourses around women’s lives with a politicised rationale (Torres San Martín 22–25). Caudeli thus actively interrogates who bears the power to tell women’s stories in cinema and how this is achieved.

In stark contrast with Porque no., Petit Mal takes place in the three main characters’ shared household, which reinforces a quintessential motif of closeness and privacy. Once again, the film is set in a secluded place. It is thus possible to determine that the narratives developed by Caudeli—both in Petit Mal and in Porque no.—are intimista (intimist), a style that Deborah Martin has examined as a means to rekindle the personal experiences and emotions of women through feminist politics and projects that were led by pioneering generations in the Colombian cinema industry (Martin 162–73). When analysing the politics attached to the work made by the Colombian feminist collective Cine Mujer (1978–99), Martin values the relevance it gave to women’s narratives of and within the private arena. Cine Mujer promoted cinema inspired by Eurocentric waves of feminism in the late twentieth century, where heteronormativity was still a main thread in their approach. And yet, it can be argued that Petit Mal and Porque no. also engage with a similar mode of representation. Remarkably, Caudeli’s approach through Petit Mal coincides with that of Cine Mujer in reclaiming, recording, and archiving lived experience of women from the most private possibility “and through a focus on women’s activity” (Martin 163) to increase the visibility of lesbian desires on-screen.

Petit Mal expands what has become prominent in other Latin American women’s filmmaking practice and is also a feature of Porque no.: a revised melodramatic convention and tendency to observe intimacy, one that documents and interprets lived experience showing “the ability to penetrate private spaces and daily life with unprecedented closeness” (Seguí 86–87). It could be argued that Caudeli’s exclusive focus on this private and isolated existence may disregard a real-life and wider social context of potential dangers surrounding the throuple, not least since “LGBTQ people in Colombia have long been targeted for who they are, much as women have, due to entrenched patriarchal norms and social and legal discrimination” (Sánchez 1). However, we argue Caudeli’s approach becomes a mechanism that invites us to look closely at the types of power relations the three women develop and maintain through the dramatisation of internal conflicts, becoming the matter privileged on-screen. With Laia’s departure, the viewer is taken into a narrative where the main events revolve around Anto and Martina and their response to Laia’s absence. Thus, the meaning of “petit mal” endures. The pain caused by Laia’s departure triggers “a type of seizure characterized by brief episodes of altered state of consciousness”.[10] This results in a two-way avenue for the two left-behind lesbian characters to re-evaluate feelings and roles in their relationship, and for deep observation of themselves and each other. Firstly, opposite to the “healing” dynamics proposed in Porque no., Anto and Martina battle forms of solitude to gradually admit the imbalances around them and sense the seeming carelessness of Laia with their relationship while she is away. In time, they consequently overhaul the meaning of the relationship they all share together. Secondly, the titular “seizure” invites the audience to witness how Anto and Martina accept themselves through a further personal, intimate, and refreshing lesbian encounter that has rarely been represented on-screen in the Colombian and Latin American contexts. They mindfully embrace the (im)possibilities of being part of the polyamorous relationship they have consented to, while also challenging the apparent dominance of Laia in their lives prior to her business trip.

The first two chapters of the film—“Es tonto, es bobo” (“It’s Foolish, It’s Silly”) and “Convulsionamos” (“We Convulsed”)—respectively explore the night before Laia’s departure, their farewell the following morning, and the initial effects caused by her absence. Visually, Caudeli experiments with a traditional technique to transition from one chapter to the other in which the distinction between past and present events is accentuated with colour for the first period, and the use of black and white for the second. Rather than deploying this as one of the most recognisable documentary conventions in cinematography to refer to each timespan, Caudeli’s creative choice suggests what Jie Li designates as the representation of a seemingly more vivid past by adding colour to certain parts of the film before subsequently adopting a more nostalgic tone for the present following Laia’s departure (248). A meaningful form of observing intimacy, as posed by Li, takes place through the predominant use of black-and-white footage in Chapters Two and Three. Using black and white becomes an additional melodramatic strategy to make the audience aware of the story’s intensity, leading us to perceive how “passions could erupt into terror, or [how] idealism might pale into disillusionment”, where the grey dreariness goes beyond the monochromatic code (Li 248, 260) (Figs. 6, 7, and 8). At the same time, the black-and-white cinematography works in consonance with the documentary norm that relates to ideas of conveying authenticity without distraction, underscoring the tragic nature and the mystery of what is being seen (Soler-Campillo and Marzal-Felici 53), as well as the heightened self-reflexive mode of the narrative (Li 260), which eventually introduces the progressive reinvention of Anto and Martina.[11]

Figures 6–8: Vivid episodes in colour (top) are often dispersed and contrasted with others shown in black and white (middle and bottom), transforming their apparently grey and tragic nature into new forms (and tones) of being. Petit Mal. Directed by Ruth Caudeli, Ovella Blava Films, 2022. Screenshots.

Alongside preferencing black-and-white cinematography over colour, intimacy is further constructed through the revised ways in which the gaze is presented in Caudeli’s film. Far from being just omnipresent or voyeuristic, a counter-gaze explores different positionalities to appreciate the lesbian woman’s perspective on-screen. Contesting gendered norms in cinema and in line with what Venkatesh examines in other Latin American films about lesbian desire, pieces such as Petit Mal “[decenter] the viewer from the purely scopic toward an experience of the moving image that is multidimensional and multisensorial” (Venkatesh 733). Echoing Porque no.’s attention to sensory detail, Petit Mal brings into play haptic poetics in cinema by employing a selection of angles, media, and textures that activate queer hegemonic ways of seeing and desiring lesbian women (Venkatesh 735). Alternative modes of the woman’s gaze manifest themselves from an early stage such as through the use of Martina’s camcorder and photographic camera as well as the women’s mobile devices to contemplate one another. The directorial gaze that was initially present through subjective views from Laia/Caudeli in Chapter One soon relocates and guides us through the spaces and emotions of Anto and Martina. In Chapters Two and Three, loneliness and pain take both characters into other forms of observation and interrogation as they face the first tensions being by themselves and eventually close together.

One of these strains on the gaze takes place in the garden during Chapter Two. As happens in different parts of the film, Martina records and archives their lives with a camcorder, to which Anto bluntly expresses: “Deja de grabar, si no estamos las tres” (“Don’t film when it’s only the two of us”). Despite the incisive reminder of the throuple’s fragmentation and Anto’s demand to stop recording, they start negotiating their difficulties. The haptic interaction between the moving images of the film and of the camcorder allows the gaze to be displaced and split between the two protagonists. Following Venkatesh and Marks, it can be said that their shared gaze goes below the surface of the image to become more affectionate, empathetic, and attentive to a multisensorial experience (Venkatesh 731; Marks 152). For instance, Martina looks constantly and closely at footage of themselves in the attempt of finding unprecedented ways to narrate their story for the project she prepares. Both Anto and Martina embrace their proximity by dancing, kissing or hugging each other in bed or in the shower. Anto goes twice to her piano to voice her grief with the melody of what becomes the main motif of the film—Petit Mal—and a reflection of their relationship. Indeed, these signs of (self)compassion provide a positive outcome. After a literal and symbolic storm experienced by each protagonist towards the end of Chapter Two, the distance between them appears to have been bridged and their gaze substitutes the purely visual and patriarchal order by privileging polysensorial and cuir registers.

As mentioned above, Petit Mal resorts to and adapts modes of documentary throughout its narrative. At the beginning of the film, Caudeli clarifies to us that the film is their real fiction. Nichols reminds us of how the different qualities of documentary are not mutually exclusive and can or should overlap to provide distinctive ways of representing the world (107). Firstly, Caudeli and her partners chose to retrospectively observe their real-life experiences, inviting the audience to play a further active role when inspecting their relationship. This dynamic takes place not only through the eyes of Anto and Martina, but also by observing with them through their use of other media. Secondly, as Nichols attests when referring to participatory documentaries, it can also be stated that by watching Petit Mal “we expect to witness the[ir] world as represented by someone who actively engages with others rather than unobtrusively observing, poetically reconfiguring, or argumentatively assembling what others say and do” (139). Just before the start of Chapter Three, “Terremoto Desigual” (“Unequal Earthquake”)—and throughout—Anto and Martina finally find themselves in a more intimate moment of their relationship. While Laia grows distant from her two partners (by not responding to their phone calls, showing limited or no interest in their projects, or complaining about not being sought by them), Anto and Martina further shift their gazes toward their own selves and mutual needs, especially after feeling sad because of missing Laia.

In formal terms, the observational and participatory modes transition to a more reflexive and dual approach. Although Anto feels sad, frightened, and lonely even with Martina nearby, and although Martina questions their relationship after her audiovisual project is rejected, the morning after the storm offers them a fresh encounter. As argued earlier with Porque no., heightened emotions drop, allowing Anto and Martina to drag themselves into a further private space to privilege the self and, in this case, other sorts of desires. Both films coincide in overcoming a sense of loss and disorientation to find some balance and resilience that was not present before. In Petit Mal, the lesbian renewed encounter is shaped by mutual contemplationat the photography dark room, inside their house. Following Liz Harvey-Kattou’s views when examining the Costa Rican film Apego (Patricia Velásquez, 2019), we argue that Caudeli’s use of camera work here is also both “affective and intimista” (175). Caudeli’s choice of bringing us into this room places us alongside these characters in one of their most private spaces, where they would not expect to be accompanied or watched (Harvey-Kattou, 175). The hapticity of the film is thus enhanced by bringing the audience closer to what the characters experience within their own home and by emphasising “the feminist gaze[s] through the creation of the protagonists’ own subjective world and time” (175). The darkroom’s red light, key to avoid ruining their craft, symbolises the necessary atmosphere and transition of the protagonists’ emotions and states of mind to observe themselves (Fig. 9). The light intensity also implies a decreased sense of nostalgia and a dash of revived sensibility about themselves as they go through a more conscious and introspective experience together.

Figure 9: Anto (back) and Martina (front), in the dark room in the process of

rediscovering their relationship through new forms of intimacy and reciprocal modes of observation.

Petit Mal. Ovella Blava Films, 2022. Screenshot.

Subsequently, the use of red enters into dialogue both with the style mentioned earlier within the work of Cine Mujer and with the reflexive mode of documentary. On the one hand, despite the generational and political limitations that Caudeli’s work and Cine Mujer have as agents of women’s narratives, Petit Mal echoes Cine Mujer’s mode of production because attention is given to “an intimate space in which women [feel] empowered to share their personal stories” regardless of gender identity or orientation, and where the usual centrality of the filmmaker is displaced to pose questions about women’s enunciation (Cervera Ferrer 158). From a political perspective, Caudeli’s reflexive techniques in Petit Mal point toward the feminist urgency of disrupting a norm to voice women’s concerns and challenge assumptions of the private. On the other hand, in contrast to what happened when Laia was present—either in person during the first and last minutes of the film or via phone calls—reflexive gestures activate a phase of self-consciousness and self-questioning. As Nichols states, “[r]eflexive documentary sets out to readjust the assumptions and expectations of its audience more than to add new knowledge to existing categories” (128). In formal terms, Caudeli once again engages with an intensified mode that defies essentialist ideas of melodramatic love and loss, as she gives relevance to Anto and Martina opening up about personal interests, preferences or complaints. Spending time together—either in the dark room, at the editing room, or at the lounge of their house the night before Laia returns—becomes a reason for Anto and Martina to shed light on the key meaning of Petit Mal. This signals what the film itself seeks: disclosing and sharing the (lesbian) self, making visible processes of grievance and (self-)acceptance, developing a heightened consciousness on the part of the spectator about alternative ways to celebrate and see their lesbian bodies, while archiving the lesbian subject through unprecedented cinematic discourses (Figs. 10 and 11).

Figures 10 and 11: Anto and Martina embrace their lesbian existence on the last night they spend on their own (left), further emphasising that lesbian women’s stories can be seen and archived from renewed perspectives (right). Petit Mal. Ovella Blava Films, 2022. Screenshots.

The gaze, which has been in ongoing transformation, is collectively and primarily established between Anto and Martina. In practice, Martina teaches Anto how to develop photographs while looking at themselves naked in the stills. With no trace of an objectifying intention, their observation triggers another cuir archival mode of self-representation as lesbian women, plausible through developing and enlarging their own photographs for posterity as well as through the clips of the throuple footage we often see. Moreover, toward the end of Chapter Three, Anto participates in an online group session that she refers to as “El Akelarre” (“The Sexual Coven”), inviting Martina to join her. Throughout the session, Anto and other individuals expand the power of their gazes in an experience of community and contemplation of the art of others. This is also where the acceptance of women’s diverse bodies proves especially essential to Anto, and where a tribute to women’s pleasures takes place, foreshadowing her sexual encounter with Martina as the climax of the “coven” she took part in. These are only two of several moments that Petit Mal constantly offers to praise ways of desiring and looking at lesbian women and that, in contrast to Porque no., allow characters to bond in the long term and articulate with openness what love and desire mean to them.

Within Martina’s film project, which happens to focus on their own real-life story too, their emotional tie foretells a necessary twist in their lives. This shift becomes dissonant and crucial for what the throuple later faces upon Laia’s return and after her own experiences outside the home—even if we have known little about them. Another mode of continuing in and observing polyamory emerges: one that is neither defined by power relations nor by specific formal strategies in filmmaking. Subsequently, Petit Mal proves its potential to reveal another form of diasporic experience, as the return of Laia/Caudeli reminds us of how her views of the world she inhabits “challenge the privileged site of the national as the space in which cultural identity and imagined communities are formed” (Higbee and Lim 11). The shift not only occurs by conceiving the gaze as not just belonging to one of them—or the director. This transformation also refers to reconnecting with the vivid present, from Chapter Four, “Escarcha estallada en la pared” (“Frost Exploded on the Wall”), understanding that their relationship has changed but still vibrates and is moving forward in constant motion (Fig. 12). In short, the new forms of seeing also stress how the throuple unites several “poder[es] secreto[s]”—the power and the skills of each one of these lesbian women—as acts of enunciation and rebellion and thus as the key manifestation of their cuir existence together.

Figure 12: Martina (left), Anto (middle), Laia (right). The gaze the throuple bears is collective, multiple, and in constant movement. Petit Mal. Ovella Blava Films, 2022. Screenshots.

Transcending Borders?

Due to the influence of the patriarchy, the connection between women, sex, and sexual diversity has historically been strained and subject to judgement. Cuir women, considered a threat to the patriarchal order often because of their “rejection” of men, have been stereotyped and ostracised for centuries in many areas and not least cinema. Although the twenty-first century has introduced a new wave of cuir and lesbian studies in the field, informed by a growing filmmaking production with similar interests dedicated to granting lesbians and cuir women visibility, it is necessary to acknowledge two issues. Firstly, the male gaze can still be pervasive and may attempt to define lesbian and cuir spaces or subjects in mainstream films. Secondly, people who identify themselves as women or lesbian/cuir filmmakers may have also internalised these strategies. Nevertheless, this article has considered material that provides visibility to this underrepresented and misrepresented community without resulting in the sexualisation or degradation of the female lesbian subject by focusing on Caudeli’s short film Porque no. and feature Petit Mal. We considered how lesbian desire and intimacy can manifest when cinematically represented in these films, exploring (sub)genres implemented by Caudeli and evaluating the embedded symbolisms within their proposed narratives. Although her work does not explicitly belong to the emblematic dissident cinema of the NLAC, it does echo what women filmmakers in Latin America have provided us with by chronicling banalities and desires, shifting to distinctive strategies and processes of emancipation that “should not be judged only on [their] aesthetic results” (Rich 281; Seguí 83). We affirm that Caudeli’s oeuvre, directed by a woman who identifies herself as feminist and cuir, continually offers an alternative representation of lesbian and cuir women that is not degrading or heteronormative, but rather personal, diverse, and overtly political.

In answer to the question we raised in the article’s title and in this conclusion, we believe the films examined here transcend certain borders beyond the geographical. For the mere fact that Caudeli deals with erotic desire in cuir contexts, her films transgress patriarchal and cinematographic norms which have historically favoured heteronormativity. Moreover, echoing the thoughts of Higbee and Lim, we appreciate that while the films studied in this article are part of an ongoing negotiation between the global and the local, indeed surpassing heteronormative hegemonic standards, they are still on the periphery of industrial practices. This limits the possibilities of evaluating the extent to which their impact goes beyond the male-dominated cinema industry in Spanish-speaking countries (Higbee and Lim 9–10). Notwithstanding, Porque no. and Petit Mal excel by underscoring the multiplicity of the self outside the binary world, even if there are tensions that cannot be resolved. The fact that the films are produced in Colombia does not limit the way these aspects represent a community within the wider region of Latin America and Spain as it does not exclusively define one context or the other but the transformations of lived experience for someone like Caudeli. Even though both pieces are formally classified as films that belong to a national boundary in terms of cast, crew, and production, they bespeak urges of lesbian and cuir women beyond national borders from first-hand perspectives.

With few exceptions across her work, Caudeli crafts cuir scenes that privilege the tender and affectionate nature within, rather than the objectifying mainstream tendency when addressing the lesbian body or intimacy between women. As discussed above, Porque no. allows us to see how Caudeli’s portrayal of lesbian desire, far from the male gaze, enables a different space for female sexuality to be perceived. Not only does Caudeli deviate from normalising same-sex interactions between women on-screen with pornography, she also provides an alternative reading of the melodramatic genre. Avoiding “happy endings”, for example, she delivers key social critique, demonstrating the risks cuir women must face when accepting or denying their homosexuality. Petit Mal contests the norm in all possible ways. First, the figure of the throuple is presented by a cuir woman filmmaker and for the first time in the context of mainstream and narrative cinema in Colombia. Second, the film is a fictionalised format of events that could be seen as life testimonials and, consequently, Caudeli adapts documentary modes to create her own version, enabling shared forms of seeing lesbian women, and opposing the observational tendency within documentary styles. Lastly, the film is made by someone whose nationality already defies the possibility of looking at this film as a solely Colombian production, as the experiences that have informed her work create new forms of existence and the self beyond a particular territory.

Part of this examination has also allowed us to infer that Caudeli consciously invests in highlighting the conflicts, tensions, and contradictions that emerge between female sexual agency and the lesbian subject. While it seems that with every transgression some codes also appear—for example, Porque no. risks supporting the trope of female hysteria, even if characters satisfy sexual desires as an answer to women’s suffering—the contradictions do not detract from the ability of her work to innovatively represent lesbians and cuir women. The characters she has built within her Colombian films contravene the patriarchal and cinematographic standards of women in general and cuir women in the context of Spanish-speaking cinema. Films such as Porque no. and Petit Mal provide a “storyspace” for lesbian and cuir women to exist on-screen using methods that are not actively tailored toward the male-based mind (Pérez-Sánchez 165). Instead, Caudeli constructs a new or even a cuir gaze, challenging not only the male gaze, but also the idea of seeing its opposition exclusively as a female or single one. Caudeli adapts and amplifies key genres to cultivate a feminist and cuir sensibility where the nature of her work goes beyond the scopic. Determining what exactly this counter-gaze is or will be could be deciphered in separate studies on Caudeli’s work or women filmmakers who, like her, make their cinema a transnational manifestation of a feminist personal and political stance on cuir existence.

Most importantly, Caudeli offers a social critique of the heteronormative, patriarchal society which still dominates twenty-first century Spanish-speaking societies and cinemas through an innovative aesthetic approach that incorporates melodrama and documentary modes when addressing female same-sex desire. Her use and reimagining of both cinematic modes, from feminist and cuir perspectives in the context of Latin America, also contributes to redefining filmmaking practices that have been male dominated. In doing so, she enriches both modes by creating interstitial and liberating spaces for lesbian and cuir expression, and by haptically writing the self outside gendered binarisms. Such disruptions facilitate encounters between subjects on-screen and cultures behind the camera despite the differences or tensions that may emerge. She is preoccupied with representing women’s diversity without relying on patriarchal modes of storytelling or filmmaking. Caudeli reclaims, records, and archives innovatively the existence of lesbian and cuir women in the context of Latin America. She leaves her audience with the overall sentiment that for the accomplishment of complete sexual agency for any woman in cinema, however “complete” may be defined, there is still progress left to be made.

Notes

[1] Our decision to include the term “cuir” here and throughout acknowledges one of several uses in the Spanish language for “queer”. While a detailed rationale for this usage goes beyond the scope of this article, we advocate the importance of interrogating how diversity and queerness should be (re)defined or (re)shaped in Global South contexts beyond the Anglosphere. We have not used “cuir” when citing direct sources where their choice has been “queer”, or when works have referred to Global North contexts, however.

[2] While matters of exhibition and (critical) reception are worth discussing in relation to how Caudeli’s films stand out among similar pieces being made in Colombia and about women, these factors go beyond the article’s scope.

[3] This article echoes what the Argentine writer Reina Roffé stressed to Tierney-Tello through personal communication when referring to how Roffé’s work responded to/exceeded socio-political constraints, namely the translation of the Spanish word “poder” to the combination of the noun power (capacity to influence; control or strength) and the verb can (to be able to).

[4] See the full list of Caudeli’s directorial work on her personal website (“Proyectos”).

[5] This certification can only be issued if productions (shorts or features) abide by the set percentages on financial, artistic, and/or technical participation within cast and crew from Colombia (Congress of Colombia, Presidency of Colombia 2.10.1.4).

[6] Formerly credited as Silvia Varón.

[7] While Santamaría and Otálora are usually leading characters in Caudeli’s films, they have played an active role behind the camera in the administrative, creative and formative processes in which the three of them engage with (Santamaría). These projects include the planning and writing process of plays or film scripts, or acting workshop cycles for television and cinema offered by Ovella Blava Films and Set de Cinema.

[8] Their melodramatic strand was expanded the following decade by renowned filmmakers, including the Spaniard Máximo Calvo, and the Colombians Arturo Acevedo, Félix Joaquín Rodríguez, and P. P. Jambrina.

[9] While “arepera”, a Latin American/Colombian slang word, has historically been used as a pejorative term for homosexual women, there have been recent reappropriations of the term as a political declaration and a form of pleasure (Enciso; García).

[10] For details, see Chapters Six and Seven in full (Nichols).

[11] Translation provided through the English subtitles of the film, as will be presented hereinafter with the additional titles and dialogues.

References

1. Alvaray, Luisela. “Hybridity and Genre in Transnational Latin American Cinemas.” Transnational Cinemas, vol.4, no. 1, 2013, pp. 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1386/trac.4.1.67_1.

2. Berger, Laura. “Women and Hollywood, Exclusive: A Throuple Hits a Rough Patch in ‘Petit Mal’ Trailer.” Women and Hollywood, 4 Jan. 2023, womenandhollywood.com/exclusive-a-throuple-hits-a-rough-patch-in-petit-mal-trailer. Accessed 4 Apr. 2024.

3. Butcher-Spellman, Cora. “Queer Melodrama.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, Oxford UP, 2023, pp. 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1245.

4. Caudeli, Ruth, director. ¿Cómo te llamas? Ovella Blava Films, 2018.

5. ——, director. Latee. 2010.

6. ——, director. La misma estación. Ovella Blava Films, Mardi Gras Film Festival, 2025.

7. ——, second unit director. Pálpito, season 1, Netflix, 2022.

8. ——, director. Petit Mal. Ovella Blava Films,2022.

9. ——, director. Poli. Ovella Blava Films,2021.

10. ——, director. Porque no.. Ovella Blava Films, 2016.

11. ——. “Proyectos”. Ruth Caudeli. https://www.ruthcaudeli.com/. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

12. ——, director. Tarde [Late]. Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuals de Catalunya (ESCAC), 2010.

Cavendish, Phil. “The Delirious Vision: The Vogue for the Hand-held Camera in Soviet Cinema of the 1920s.” Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, vol. 7, no. 1, 2013, pp. 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1386/srsc.7.1.5_1.13. Cervera Ferrer, Lorena. “Towards a Latin American Feminist Cinema: The Case of Cine Mujer in Colombia.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 20, 2020, pp. 150–65. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.20.11.

Chanan, Michael. “El documental y la esfera pública en América Latina: notas sobre la situación del documental en América Latina, 14. comparada con cualquier otro sitio.” Secuencias, no. 18, 2003, pp. 22–32, hdl.handle.net/10486/3894.

15. Chaparro Valderrama, Hugo. “Cine Colombiano 1915–1933: la historia, el melodrama y su histeria.” Revista de Estudios Sociales, no. 25, 2006, pp. 33–37. https://doi.org/10.7440/res25.2006.04.

16. Congress of Colombia. Ley 397 de 1997: Por la cual se desarrollan los Artículos 70, 71 y 72 y demás Artículos concordantes de la Constitución Política y se dictan normas sobre patrimonio cultural, fomentos y estímulos a la cultura, se crea el Ministerio de la Cultura y se trasladan algunas dependencias. 7 Aug. 1997. Republic of Colombia. www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=337.

17. Dadar, Taraneh. “Framing a Hybrid Tradition: Realism and Melodrama in About Elly.” Melodrama in Contemporary Film and Television, edited by Michael Stweart, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 223–38.

18. De Lauretis, Teresa. “Rethinking Women’s Cinema: Aesthetics and Feminist Theory.” New German Critique, no. 34, 1987, pp. 154–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/488343.

19. Di Domenico, Francesco, and Vincenzo Di Domenico, directors. El drama del 15 de octubre [The Drama of 15 October]. Di Domenico Hermanos, 1915.

20. Doane, Mary Ann. “The Woman’s Film: Possession and Address.” Home Is Where the Heart Is: Studies in Melodrama and the Woman’s Film, edited by Christine Gledhill, British Film Institute, 1987, pp. 283–98.

21. Durovicová, Nataša. “Preface.” World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives, edited by Nataša Durovicová and Kathleen E. Newman, Routledge, 2010, pp. ix–xv.

22. Ellis, Havelock. “Hysteria in Relation to the Sexual Emotions.” Alienist and Neurologist, vol. 19, no. 4, 1898, pp. 599–615.

23. Elsaesser, Thomas. “Tales of Sound and Fury: Observations on the Family Melodrama.” Film Genre Reader IV, edited by Barry Keith Grant, U of Texas P, 2012, pp. 433–62. https://doi.org/10.7560/742055.

24. Enciso, Andrea Juliana. “Machorras y areperas en espacios públicos en Colombia.” Queering Paradigms IVa: Insurgências queer ao Sul do equador, edited by Sara Elizabeth Lewis et al., 2017, pp. 221–45.

25. Erens, Patricia, editor. Issues in Feminist Film Criticism. Indiana UP, 1990.

26. García, Alejandra Morales. “Lesbiana no es un insulto. Es un placer político y orgásmico.” Agenda Cultural Alma Máter, no. 265, 2021, pp. 12–15, evistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/almamater/article/view/338630.

27. Gaines, Jane. “Women and Representation: Can We Enjoy Alternative Pleasure.” American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives, edited by Donald Lazere, U of California P, 1987, pp. 357–72. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520906846-036.

28. Gorton, Kristyn. Theorising Desire: From Freud to Feminism to Film. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

29. Harris, Ruth. “Melodrama, Hysteria and Feminine Crimes of Passion in the Fin-de-Siècle.” History Workshop, vol. 25, no. 1, 1988, pp. 31–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/25.1.31.

30. Harvey-Kattou, Liz. “Creating a Feminist Gaze? Motherhood and Identity in Recent Costa Rican Cinema.” Female Agency in Films Made by Latin American Women, edited by María Helena Rueda and Vania Barraza, Palgrave Macmillan, 2025, pp. 169–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72600-2_8.

31. Higbee, Will, and Song Hwee Lim. “Concepts of Transnational Cinema: Towards a Critical Transnationalism in Film Studies.” Transnational Cinemas, vol. 1, no. 1, 2010, pp. 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1386/trac.1.1.7/1. Accessed 5 June 2025.

32. Johnston, Claire, and Pam Cook. “The Place of Women in the Films of Raoul Walsh.” Raoul Walsh, edited by Phil Hardy,Edinburgh Film Festival, 1974, pp. 92–109.

33. Kaplan, E. Ann. “Theories of Melodrama: A Feminist Perspective.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 1, no. 1, 1983, pp. 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407708308571052.

34. King, John. Magical Reels: A History of Cinema in Latin America. Verso, 2000.

35. Kleinhans, Chuck, and Julia Lesage. “The Politics of Sexual Representation.” Jump Cut,no. 30, 1985, pp. 23–26, www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC30folder/PoliticsSexRep.html.

36. Kratje, Julia. “El cine como transgresión: Deseo, política y feminismo en Camila (María Luisa Bemberg, 1984).” La trama de la comunicación, vol. 21, no.1, 2017, pp. 29–43, https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=323950142002.37. Levine, Stephen B. “Reexploring the Concept of Sexual Desire.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, vol. 28, no, 1, 2011, pp. 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262302317251007.

38. Li, Jie. “Discoloured Vestiges of History: Black and White in the Age of Colour Cinema.” Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol.6, no. 3, 2012, pp. 247–62. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcc.6.3.247_1.

39. Lipton, Briony, and Elizabeth Mackinlay. We Only Talk Feminist Here: Feminist Academics, Voice and Agency in the Neoliberal University. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40078-5.

40. López, Ana M. “Tears and Desire: Women and Melodrama in the ‘Old’ Mexican Cinema.” The Latin American Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Ana Del Sarto et al., Duke UP, 2004, pp. 441–58. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385462-023.

41. Marks, Laura U. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Duke UP, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822381372.

42. Marshment, Margaret. “The Picture Is Political: Representation of Women in Contemporary Popular Culture.” Introducing Women’s Studies: Feminist Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Robinson and Diane Richardson. Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, pp. 125–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-22595-8_6.

43. Martin, Deborah. “Mother’s Body, Daughter’s Voice: Female Genealogy, Invasión and Cinema in La Mirada de Myriam.” Painting, Literature and Film in Colombian Feminine Culture, 1940–2005: Of Border Guards, Nomads and Women, Boydell & Brewer, 2012, pp. 162–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781782040910-012.

44. Mdege, Norita. Cinematic Portrayals of African Women and Girls in Political Conflict. Routledge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003388265-1.

45. Mercer, John and Martin Shingler. Melodrama: Genre, Style, Sensibility. Columbia UP, 2013.

46. Mourenza, Daniel. “Death of a Subaltern: Melodrama, Class and Victimhood in Muerte de un ciclista (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1955) and La mujer sin cabeza (Lucrecia Martel, 2008).” Bulletin of Spanish Visual Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 2023, pp.15–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/24741604.2021.1974761.

47. Mulvey, Laura. “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6.

48. ——. Visual and Other Pleasures.Palgrave Macmillan, 1989.

49. Newman, Kathleen. “Notes on Transnational Film Theory: Decentered Subjectivity, Decentered Capitalism.” World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives, edited by Nataša Durovicová and Kathleen E. Newman, Routledge, 2010, pp. 3–11. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203882795-8.

50. Nichols, Bills. Introduction to Documentary. 3rd edition,Indiana UP, 2017, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005t6j.

51. Ortega, María Luisa. “Rupturas y continuidades en el documental social.” Secuencias, no. 20, 2004, pp. 47–61, http://hdl.handle.net/10486/3907.

52. Ortega, María Luisa, and Ana Martín Morán. “Imaginarios del desarrollo: un cruce de miradas entre las teorías del cambio social y el cine documental en América Latina.” Secuencias, no. 18, 2003, pp. 33–48. https://doi.org/10.15366/SECUENCIAS2003.18.003.

53. Padva, Gilad. “Edge of Seventeen: Melodramatic Coming-Out in New Queer Adolescence Films.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 4, 2004, pp. 355–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/1479142042000244961.

54. Pérez-Sánchez, Gema. “Transnational Conversations in Migration, Queer, and Transgender Studies: Multimedia Storyspaces.” Revista Canadiense de Estudios Hispánicos, vol. 35, no. 1, 2010, pp. 163–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23055673.

55. Ponce de León, Gina. “Colombian Queer Narrative.” A History of Colombian Literature, edited by Raymond Leslie Williams, Cambridge UP, 2016, pp. 342–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139963060.019.

56. Presidency of Colombia.Decreto 1080 de 2015: Por medio del cual se expide el Decreto Único Reglamentario del Sector Cultura. 26 May 2015, updated on 19 Jan. 2023, https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=76833.

57. Rich, B. Ruby. “An/Other View of New Latin American Cinema.” New Latin American Cinema, Vol. 1: Theory, Practices and Transcontinental Articulations, edited by Michael T. Martin, Wayne State UP, 1997, pp. 273–97.

58. Rivera Betancur, Jerónimo León. “Research on Colombian Cinema.” Communication Research Trends, vol. 29, no. 2, 2010, pp. 15–24, http://hdl.handle.net/10818/32349.

59. ——. El papel del cine colombiano en la escena Latinoamericana. Universidad de la Sabana, 2019.

60. Rowe, Kathleen. “Comedy, Melodrama and Gender: Theorizing the Genres of Laughter.” Classical Hollywood Comedy, edited by Kristine Brunovska Karnick and Henry Jenkins, Routledge, 1994, pp. 39–59.

61. Rueda, María Helena. “Intimate Documentaries Made by Women in Colombia: Beyond the Patriarchal Gaze.” Female Agency in Films Made by Latin American Women, edited by María Helena Rueda and Vania Barraza, MacMillan, 2024, pp. 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-72600-2_4.

62. Sánchez, Marcela. “UN Security Council Briefing on Colombia by Marcela Sánchez.” NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. 9 Apr. 2024. www.womenpeacesecurity.org/resource/un-security-council-briefing-colombia-marcela-sanchez.

63. Santamaría, Silvia. Personal interview. 5 Oct. 2023.

64. Seguí, Isabel. “Beatriz Palacios. Ukamau’s Cornerstone (1974–2003).” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 48, no. 2, 2021, pp. 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X20988693.

65. Seiter, Ellen. “Stereotypes and the Media: A Re-evaluation.” Journal of Communication, vol.36, no. 2, 1986, pp. 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1986.tb01420.x.