Speaking With: Histories of Vietnam Explored Through Archive Film

Esther Johnson

[PDF]

Abstract

This article discusses the research and methods undertaken in the creation of the poetic documentary feature film Dust & Metal (Cát bụi & Kim loại), directed by Esther Johnson (2022). Funded by the British Council, the film offers alternative perspectives of Vietnam, moving beyond Hollywood’s portrayals of the American/Vietnam War. Through a combination of difficult-to-access archive film, crowd-sourced material, newly shot footage, and oral histories, the research reveals unfamiliar histories of freedom in Vietnam that connect with the country’s most ubiquitous mode of transport: the motorbike and, previously, the bicycle. Dust & Metal concurrently acts as a whistle-stop tour through the history of Vietnamese cinema as shot by the film studios supported by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture.

Dossier

The Vietnam-born, US-based artist, author and composer Trinh T. Minh-ha introduced the idea of “speaking nearby” as a filmmaking approach, in which speaking “does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place” (Chen 87). A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject, without however seizing or claiming it, “is an attitude in life, a way of positioning oneself in relation to the world” (87). In my film Dust & Metal (Cát bụi & Kim loại, 2022), I aimed to “speak nearby” but also “speak with” collaborators to simultaneously reveal a plurality of unfamiliar social histories of Vietnam through a scripted collage of oral testimonies and historical research, alongside a synthesis of newly shot footage and carefully chosen extracts of Vietnam’s film heritage, a relatively underseen body of Southeast Asian cinema.

Background

My introduction to Vietnamese film as a student was Việt Linh’s dazzling 1988 drama Gánh xiếc rong (Travelling Circus).[1] Watching this film whetted my appetite to further explore Vietnamese film heritage. Whilst Vietnamese films are occasionally screened on television, and selected titles are available on DVD in Vietnam, I soon discovered the difficulties of accessing classic Vietnamese cinema outside of Vietnam. With the rise of YouTube, many classic Vietnamese drama films have become available online; however, they are often heavily edited or of poor quality (occasionally, recordings of television broadcasts or rips from DVD), and/or without reliably translated subtitles for non-Vietnamese speakers.[2] The genesis for the Dust & Metal research came from this desire to learn more about Vietnamese film and cultural heritage, and to explore the potential for repositioning seldom-seen archive film sourced from the state-controlled Vietnam Film Institute (VFI, Viện Phim Việt Nam) into a new poetic documentary that could be performed with a live score.[3] Principally, the research was conceived as a work that would highlight the complex interrelation of cinema, nationhood, and history, taking viewers on an unorthodox tour of Vietnamese film heritage while simultaneously proposing a journey through past and present social histories of Vietnam that deviate from American cinematic portrayals of the 1955–1975 war. The research reveals unfamiliar histories of freedom in Vietnam that connect with the country’s most ubiquitous mode of transport: the motorbike and, previously, the bicycle. With a population of over 101 million (“Vietnam Population”) and 77 million registered motorbikes (Huyen)—one of the highest percentages globally—that is equivalent to 7.7 motorcycles for every ten people, motorcycles representing 95% of vehicles on the road. This isn’t surprising given the country’s infrastructure, with urban roads and “hẻm” alleys being only accessible by two wheels. Vietnam roads are overflowing with the transportation of goods of all types and sizes, transported on the back of motorbikes. On my first trip to Vietnam, I wrote a long list of all the things I witnessed being carried by bike, these included wardrobes, washing machines, and entire families, including pets. The bicycle theme in Dust & Metal concurrently stems from a childhood memory of a National Geographic Vietnam photo-essay (each Christmas, I was gifted a subscription) with astonishing images of streets dense with bicycles and motorbikes, scenes I wanted to experience for myself, stepping into and embodying the photographs remembered as a child.

Mirroring the complex and multilayered histories of Vietnam and its unique film heritage, the title Dust & Metal can be read on an abstract philosophical level, but also in a literal sense. The use of the ampersand (the typographic term originating from the ligature of et, meaning Latin for and) is used as a bridge to make two things belong to one another. I wanted Dust & Metal to be a filmic dérive rooted in the landscapes of Vietnam, and of people having the freedom of a bike to roam the land. Here, the “dust” of the land coexists with the harsh “metals” beneath that can be altered by manmade technology to serve our will in the metal bodywork of bikes. While researching the project, I frequently came across multiperspectival references to “dust” in Vietnamese literature, poetry, and song. For instance, “Cát Bụi” (“Sand and Dust”) by musician and songwriter Trịnh Công Sơn includes the lyrics, “What speck of dust will become my destiny, / So that one day I will return to dust” (my trans.)—a reminder of the cycle of life. This sentiment is present throughout Dust & Metal in terms of honouring ancestors and people’s connection to their heritage and land, allowing one to imagine and project new futures. I wanted the film to look to the past whilst being rooted in the present. The “dust” is what survives in the present—the indelible marks of life and history. “Dust” is permanent and infinite.

Support and Partnerships

In 2019, my Dust & Metal proposal for a British Council-supported research and development trip to Vietnam was successful. The trip aimed to foster creative crosscultural collaborations between the UK and Vietnam. After an initial Vietnam trip in June 2019, I teamed up with Live Cinema UK to apply for the British Council’s FAMLAB: Film, Archive, Music Lab and Heritage of Future Past grants. The funding received allowed for a further Vietnam trip in November 2019, where I was able to undertake initial filming and to discuss the project vision in more detail with the VFI team. I also began on-site research in the VFI archives.

Figure 1 (left): Vietnam Film Institute (VFI) with archive staff. Figure 2 (right): Esther Johnson (right) undertaking archive film research at the VFI with archive staff. Images by Esther Johnson, 2019.

In 2020, Dust & Metal was among eight projects to be funded by the British Council’s first Digital Collaboration Fund – Restart Grants, established in response to the global pandemic. Most of the film’s production took place during international lockdowns in 2020–21 and therefore necessitated creative methods of remote coproduction for the partners in the UK, Vietnam, and the US.

Having worked with UK, US, and Swedish archives in previous research, I wanted to explore archives further afield to study film heritages that are either unseen or seldom-seen outside of their country of origin.[4] As Dust & Metal was designed to showcase unconventional perspectives of Vietnam’s cultural heritage and its unique national cinema, access to archival film shot by Vietnamese film crews in Vietnam was essential for the project. With the help of the British Council team in Vietnam, I was able to visit the VFI to discuss the proposed project and collaboratively navigate how I might negotiate access and work with the archive team, especially as they had not previously partnered with a filmmaker for an archive-based collage feature film. Dust & Metal is the first film for which the Vietnam Ministry of Culture Cinema Department granted VFI partnership permission. Though difficult to secure, access to the VFI allowed me to be immersed in and to learn more about the Vietnamese film heritage of all genres shot under the umbrella of the ministry studios.

As no model existed for artists or filmmakers to negotiate copyright for the reuse and “repositioning” of archive film into new works in Vietnam, the VFI and I needed to create a working process for the project and negotiate copyright for international screenings. As part of this there was the challenge of how best to navigate the Ministry of Culture Cinema Department and the layered censorship process in Vietnam. The research has resulted in the first partnership of its kind not only with the VFI, but also with Hanoi-based TPD: The Centre for Assistance and Development of Movie Talents (Trung tâm hỗ trợ Phát triển tài năng Điện ảnh). Crucially, TPD led the complex procedure of submitting the film treatment, script, and completed film to the Ministry for the necessary permissions in Vietnam and internationally. Sensitivities regarding pre-1975 footage and references to the war in Vietnam, and whether there was archive film I would not be allowed to access, were all significant considerations. Partnering with TPD was an excellent sounding board for thinking about such sensitive and delicate territory.

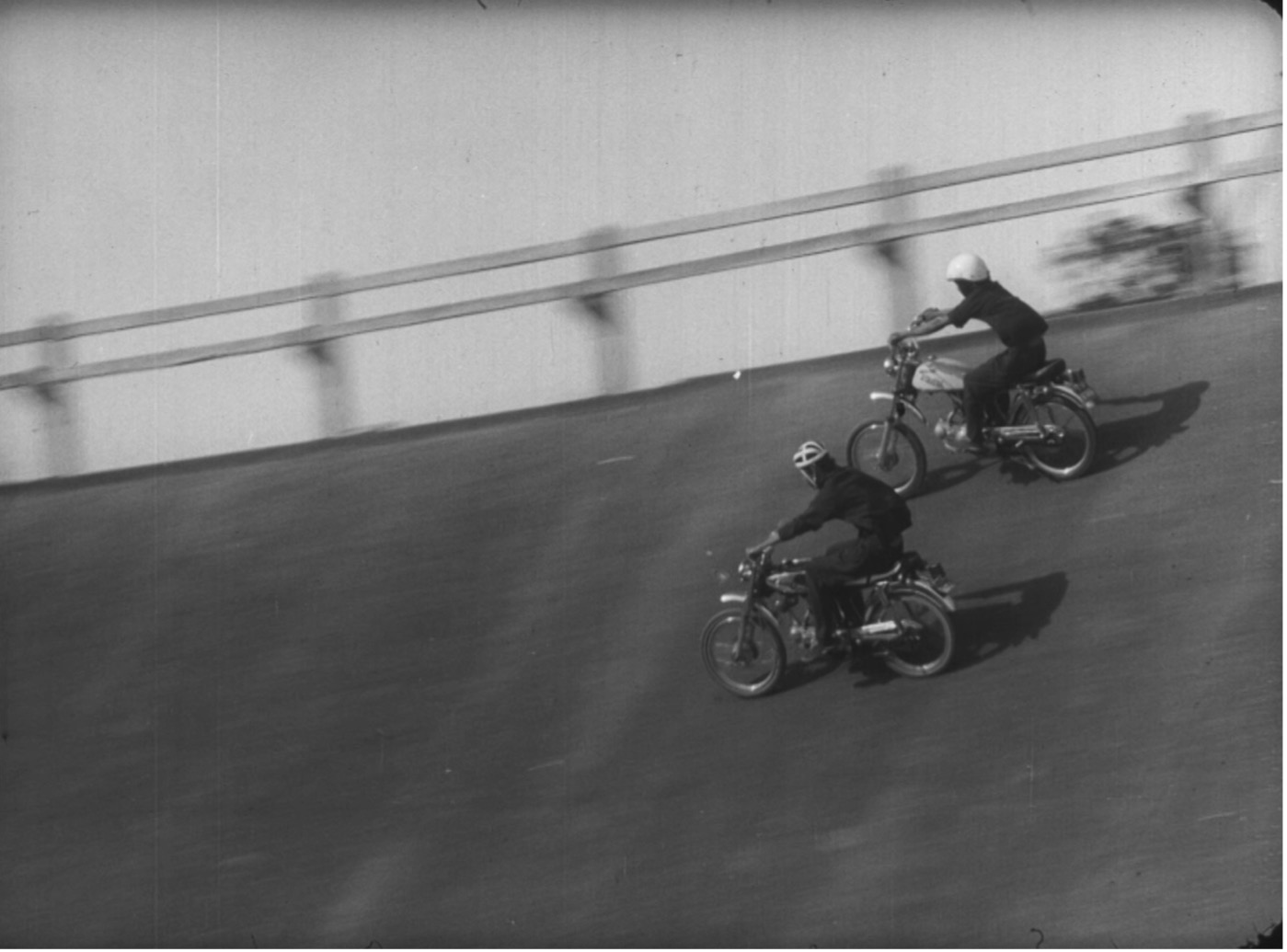

Figure 3: Motorcycle Defence Team film still included in

Dust & Metal (Cát bụi & Kim loại), directed by Esther Johnson, 2022.

Much of the footage selected for the final film edit was either unseen or rarely seen outside of Vietnam, and most of the documentary, newsreels, and high-quality prints of the drama films had scarcely ever been screened both inside and outside of Vietnam. One impact of the research was for the Dust & Metal sampled film from VFI’s collection to be accessible to a wider audience in future. To enable this, the sampled films, previously only available on 16mm or 35mm film, were digitised via the in-house Golden Eye III 2K film scanner. The digital copies of these films can now be screened in their entirety to a wider audience, with the master film copies preserved from further deterioration from being projected or viewed via a flatbed film editor. Due to restrictions on international travel during the pandemic, the bulk of the research had to be accomplished remotely, so I sourced footage with the help of an assistant researcher in Hanoi and archivists at the VFI. I made detailed spreadsheet databases to log and organise the countlessf films I was reviewing, and to make notes on metadata and timecodes of clips of specific interest. The spreadsheets also incorporated information on the kinds of footage I was keen to incorporate into Dust & Metal, with a list of key themes and storylines that featured in the film script. Columns were divided into footage types, styles, and themes; sounds, music and SFX featured in the films; the richness and texture of onscreen graphics; and the colours and tone of footage. As I aimed to explore the history of Vietnamese cinema, I selected films produced by the various Vietnam Ministry film studios, with a diversity of genres shot across different decades, including drama feature films, documentaries, newsreels, animations, and rhythmic abstract footage with unusual framing. My spreadsheets were shared with all team members as a springboard for discussion and a source of inspiration, especially for the production score and sound design. The completed film includes clips from over ninety films, with more than 3,000 individual clips forming a curated sample of the breadth of Vietnamese film heritage shot under the umbrella of Vietnam’s Cinema Departments: a glimpse of the 82,000 16mm and 35mm film reels held at the VFI. The end credits for Dust & Metal list each sampled film clip, including the year, title, director, cinematographer, and film studio. As I could not source a detailed history of Vietnam film studios during my pandemic research, it took time to unpick the complexities of which films belonged to which Ministry film studios. Among the jewels in the archive, some of the most unexpected footage found was unearthed in response to the historical research I had undertaken and shared with the VFI. For example, I had discovered that the Vietnamese Army had a Motorcycle Defence Team during the 1955–75 war, comprising young women and men, some still teenagers. This was news to me and the VFI staff. When I asked if they might have any footage of the team in newsreels, they miraculously found some. It was exciting to have the opportunity to include a sequence in Dust & Metal of footage dedicated to this gung-ho team (Fig. 3).

Figure 4 (left): TPD production filming in Hanoi, 2020.

Figure 5 (right): Remote screening at TPD with director Q&A, 2020.

TPD acted as line producers for liaising with the VFI and organised the production crew in Vietnam to shoot sequences of new footage when international travel was restricted. In preparation for filming, we held a virtual screening and question-and-answer session at TPD with a focused discussion on the reuse and repositioning of archive film in new works, screening my feature film Asunder (2016) as a case study (Fig. 5). Supplementary to the new footage TPD shot, and material I filmed in November 2019, and in response to difficulties accessing archive materials in Vietnam and during the pandemic, members of the public were invited to remotely upload their own film footage via an online submission form available in Vietnamese and English language. This method of crowdsourcing was also an attempt to capture a third pool of audiovisual material potentially missing from official state archives, and a means of creating a new collection of film relating to Vietnam. A selection of the submitted video footage was integrated into Dust & Metal, and each contributor was paid. This crowdsourced material is now publicly accessible via the project website for others to freely reuse and remix, for noncommercial purposes, via a Creative Commons license. This process engaged a community of visual makers to participate in the project during the difficult pandemic restrictions. Some people submitted footage they already had, as they now had the time to search their personal collections and offered the chance to connect with potential future audiences for Dust & Metal.

Alongside the alternative perspectives of Vietnamese cultural heritage told through the synergy of archive, new, and crowd-sourced footage, Dust & Metal has a new score composed and performed by San Francisco-based electronic artist Xô Xinh with sound design by Hanoi-based artist Nhung Nguyễn. A voiceover narrative is performed by eminent Vietnamese actress Lan Hương Nguyễn from my original script, which was informed by historical research and original oral testimonies I recorded, as I will discuss later.[5]

Why Archive Film?

In recent years, the word archive has arguably been used too broadly and as a result has almost become stripped of its specificity. The very definition of “Archive” in the Oxford English Dictionary is: “A historical record or document so preserved; and, to place or store in an archive.” In my research, material for creative reuse may come from many sources: both “official state archives” and unofficial “counter archives” that could include collections of material owned by individuals, or small collections run by volunteers that may include items that better-funded archives deem unworthy of preservation.

In William Faulkner’s 1951 novel Requiem for a Nun, he wrote,“The past is never dead, it’s not even past” (73); whilst Hannah Arendt discusses the gap between past and future being, “[the] only region perhaps where truth eventually will appear” (14). For me, these quotes sum up the potency of working with archive material and how it can be full of clues, mysteries, and hauntings. All archives are the domain of “absence” as much as “presence”, and I am particularly interested in these gaps and the slippages between past and present and between personal and collective history. A powerful factor of archive film is how one can witness a specific period and place as it unfolds in the past, while simultaneously being outside of time and looking at the past from the present tense. With this immediacy, I try to inhabit a form of visual listening when researching archive film, and to be alive to moments when serendipity takes over and material self-determines a narrative flow. I look for something special in archive images that others may have discarded or ignored, then weave these distinct threads into a coherent new whole. Spinning a web from these extracts and leftovers allows one to glimpse possible futures found in the past and inject new life into something that may have been forgotten. There is a magic in the making of such connections and envisaging the potential in disparate elements to create a new filmic tapestry.

Social Histories and Creative Nonfiction

Reality is shaped to be read like fiction in many documentary films. For me, some of the most memorable works of creative nonfiction are those in which the moments of “reality” are pushed into the reflexive realm of the poetic and magical, or articulating a sequence of thought as exemplified in essay films. Writing on truth, Trinh T. Minh Ha eloquently stated that, “on the one hand, each society has its own politics of truth; on the other hand, being truthful is being in the in-between of all regimes of truth. Outside specific time, outside specialized space” (121), and that “filmmaking is not all about stories or messages. Those come along, but they can’t define cinema” (Minh-ha and Mercier).

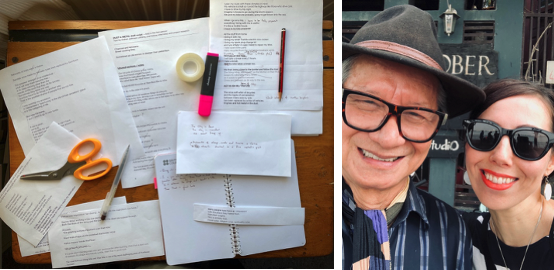

Figure 6 (left): In-progress scriptwriting integrating oral history transcripts and project research.

Figure 7 (right): Filmmaker Trần Văn Thủy with Esther in Hanoi, 2019. Images Esther Johnson.

My practice-based research offers alternative perspectives of social histories of resistance and the connections between people and place. For instance, the backbone of the script for Dust & Metal blends a poetic approach to “histories from below” gleaned from oral histories I recorded, with historical research and archival material.[6] The creative use of oral histories—as both voiceover narrator and storyteller—embraces many voices and is woven together with history and elements of imagination and creative writing. The below poetic description of the feeling of riding a bike, rather than solely facts about bikes, is one such example of this:

Travelling on two wheels, the mind arrives at wondrous things.

Walking is too slow.

Driving a car too fast and contained.

The pace of a bike allows me to feel space as in no other way.

A floating state of mind.

The rhythm of dreamers.

We live in the present on our motorcycles.

No future and no past.

Khi di chuyển trên chiếc xe hai bánh,

thế giới quan như được mở ra.

Đi bộ thì quá chậm.

Ô tô thì quá nhanh, quá gò bó.

Chỉ có nhịp điệu của xe máy, xe đạp

mới cho ta cảm quan không gian này.

Tâm trí bay bổng.

Nhịp điệu của những kẻ mơ màng.

Trên chiếc xe máy, ta sống ở hiện tại.

Không tương lai, không quá khứ.My oral history interviewees included eminent Vietnamese documentary filmmaker Trần Văn Thủy, who began his career in 1960 as an ethnographic cameraman for the Lai Châu Department of Culture, and from 1966–69 was a war cameraman in the 5th Military Region (Quân khu 5) of the Vietnam People’s Army (Fig. 7).[7] Secondly, I interviewed Đặng Ái Việt, an artist who has travelled over 36,000 km to over sixty-three different provinces and cities across Vietnam on her trusted Honda “Chaly” scooter to paint hundreds of portraits of Heroic Mothers of Vietnam, women who lost loved ones during the wars in Vietnam. I came across Ái Việt in the Vietnamese Women’s Museum and was struck by how essential her scooter has been to access and create such important and unique artworks recording social histories from a generation who are rapidly disappearing (Fig. 8). My interviews were conducted in Vietnamese with the aid of translators, then transcribed and translated into English as source material for scriptwriting. The final script in English was then translated back into Vietnamese with the help of several translators in order that tone and meaning were not lost. The script includes many verbatim quotes from these oral histories.

Figure 8: Đặng Ái Việt’s scooter in the Vietnamese Women’s Museum in Hanoi, 2019. Image Esther Johnson.

The Dust & Metal script also incorporates attendant project research from a diverse selection of material, including poetry and verse, philosophy, photography, people’s histories told via memoirs, diaries and autobiographies, and unfamiliar stories of the significance of bicycles and motorbikes during warfare in Vietnam. The film’s end credits include references to all individuals quoted in the script.

Narratives of Freedom and BikesCollective and individual freedoms differ significantly, and the notion of freedom can be interpreted in many ways, especially depending on one’s background, personal ethics, and politics. The word “freedom” is ever-present in the writings of Ho Chi Minh (Nguyễn Sinh Cung) for example, “Nothing is more precious than independence and liberty”, a famous phrase that features in Dust & Metal via an extract from Hải Ninh’s film The Little Girl of Hanoi,in which the quote is painted on a banner draped across Long Bien Bridge. Throughout Dust & Metal, “freedom” is referred to in how bikes afford a sense of individual emancipation and the possibility of living “in the moment”, riding as a means of escape and reverie.

Suffragist Susan B. Anthony wrote in 1896, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling […] I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel. It gives woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. It makes her feel as if she were independent” (Bly). Liberating women and endowing them with independence (freedom of movement without a chaperone) and the means to socialise and organise, the advent of the bicycle in the late nineteenth century, and later motorbikes, has also been transformational for countless people all over the world. As an affordable means of transport that was hitherto unavailable, it was of particular importance to the working classes, opening all kinds of opportunities in terms of travelling for work and leisure. Besides use for work and travel, the history of bikes in Vietnam has unique roots in the struggle for liberation from occupation. During the wars in Vietnam, “pack bikes” (also known as “steel horses” or Xe Tho) were vital in transporting supplies across the vastly difficult terrain of the jungle, landscapes only navigable on foot or two wheels. In preparations leading to the 1954 Battle of Diên Biên Phú, General Võ Nguyên Giáp ordered Peugeot bicycles to be converted so they could each carry 500 pounds—more weight than the average elephant can carry. The resultant military bicycle-transport of 60,000 bicycle-pushing porters is reported as the largest such feat in history (“Bicycle”). In the 1960s, on his return from a trip to Hanoi, the New York Times journalist Harrison Salisbury testified before the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate that,

Bicycles, which are manufactured in North Vietnam, are vital to every aspect of life […] The best present you can give your girlfriend in Hanoi is not a box of candy or even a diamond ring. It’s a new chain for her bicycle […] The bicycle is just as essential to the North Vietnamese as the auto is in Los Angeles. Without the bicycle Hanoi’s life would come to a halt. If by some magic weapon all the bikes in North Vietnam could be immobilized, the war would be over in a twinkling […] The bicycle is the key to transport in the country as well as in Hanoi. It is the bicycle that carries fantastic burdens when rail and truck links are impeded by bombing. (99)

This historical research was woven into the Dust & Metal script here:

When bicycles were the pride and joy of families,

the best present you could give your girlfriend in Hà Nội wasn’t a box of candy or even a diamond ring, but a new chain for her bicycle.

Potential grooms who owned a bike were favoured.Cái thời xe đạp là niềm tự hào của một gia đình,

món quà tuyệt nhất ta có thể tặng người thương

không phải là hộp kẹo hay nhẫn kim cương,

mà là xích mới cho xe đạp nàng.

Các chàng rể có xe đẹp sẽ dễ lọt mắt xanh nhà cô dâu.

Similarly, some verses from Ho Chi Minh’s Prison Diary were synthesised into the script:“Long Detention Without Interrogation”

A bitter drug tastes all the more bitter when the cup is almost empty.

The last stage of a hard journey is often the hardest of all.

To the mandarin’s residence the distance is no more than one li:[8]

Why then for so long have I been kept in thrall? (107)

My road trips aren’t for fun.

My purpose is very different.

Both the journey and the return are hard.

“The last stage of a hard journey is often the hardest of all”, said Hồ Chí Minh.

“Hard trials shape us into polished diamonds.”

Tôi đi không phải để chơi.

Tôi mang trong mình một mục đích hoàn toàn khác.

Cả chuyến đi lẫn chuyến về đều vất vả.

Hồ Chí Minh từng nói, “chặng cuối [cũng] là lúc

gian nan nhất.”

“Khó khăn mài giũa ta thành viên ngọc.”

During my discussions with Trần Văn Thủy, we spoke of personal freedoms, and he expressed how in classic Vietnamese cinema it had been hard to forefront the “self” as the collective socialist ideal was encouraged as the focus of films. With the single voice narrator in Dust & Metal, scripted from multiple sources, I attempted to enmesh the ideas of self and collective and offer a glimpse of the personal inside the collective across time and space. This idea of being across, and out of time and space, is in the spirit of Hannah Arendt, also quoted:

“To think with an enlarged mentality”, wrote Hannah Arendt, “one trains one’s imagination to go visiting.”

Ha-na Ây-rừn từng viết, “Để mở mang trí óc’

‘ta phải luyện cho trí tưởng tượng đi xa.”

Screenings and Conclusion

Dust & Metal was designed to premiere with a live score and later as a standalone film with an integrated soundtrack. Live scores to films can be a bridge to transport the audience somewhere else while also being anchored very much in the present through their “liveness”. For this reason, live scores can work particularly well with archive collage films. Partnering with Live Cinema UK as coproducer of the project was ideal due to their experience and expertise in this area. Whereas Asunder premiered with a live score performed by an orchestra and three bands, Dust & Metal premiered at the 2022 Sheffield Doc Fest with a single performer.[9] Collaboration with Vietnamese American-based electronic composer Xô Xinh was a result of seeing him perform at the 2019 Hanoi Monsoon Music Festival, where I was an invited panel speaker to discuss archive film and live music. The resulting electronic score explores traditional Vietnamese music, and the pentatonic scale performed on analogue Moog synthesisers. In addition to Xô’s newly scored music, the film also includes a 1960s track Em Tập Lái Vespa (“I Practice Vespa”) over the end titles.[10] I resisted having English subtitles for the Vietnamese lyrics of this end song, allowing a moment solely for Vietnamese speakers.

Figure 9 (above left): Dust & Metal film poster designed by Christopher Wilson.

Figures 10–11 (above right and below): Dust & Metal Vietnam premiere in Hanoi.

In June 2023, I was invited by the VFI to speak about Dust & Metal at a two-day forum “Connect to Develop Viet Nam’s Tourism Through Cinema”, organised by the Vietnam Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, and hosted in Nha Trang City, Khanh Hoa Province, a popular beach resort. Discussions at this forum included the difficulties of access to Vietnamese film heritage, copyright, censorship, and the importance of the future sharing of Vietnam’s rich cinema heritage to both Vietnamese and international audiences. In October 2023, the Vietnam premiere of Dust & Metal with a live score from Xô Xinh took place at Nguy Nhu Kon Tum Hall as part of the 2023 Hanoi Monsoon Music Festival, and at Nam Ky Khoi Nghia in HCMC. A further screening without the score live took place at the Seagate Creative and Cultural Space (Chu Bien) in Hai Phong. All screenings were followed by question-and-answer sessions.

As part of a BFI-supported programme Star Nhà Ease: Vietnamese Cinema that I co-curated in May 2024, Dust & Metal toured with Xô Xinh performing live at Rich Mix, London, MAC, Birmingham, and Pagoda Arts, Chinese Community and Youth Centre, Liverpool. Xô and I participated in post-screening question-and-answer sessions alongside a member of the TPD team. Additional screenings to date have taken place in cinemas across the UK and France.

The Dust & Metal project expanded to include film workshops with young Vietnamese creatives in Hanoi and HCMC, in which we gave students access to some of the raw new footage and audio files recorded for the project and invited them to make “One Minute Remix” films from these materials. These workshops were delivered online and in person with me, Xô Xinh, sound designer Nhung Nguyễn, and staff from TPD. Workshop attendees were enthusiastic to experiment in the form of collage filming and learn about the process of making Dust & Metal. The resulting films premiered in Hanoi, followed by a networking session for young Vietnamese creatives, and were later screened at London’s Museum of the Home as part of the 2024 UK tour.

Figure 12: Social Media banner for the One Minute Remix workshops.

In response to international travel restrictions during Covid lockdowns, and the rise of “hologram” performances, a portable hologram cabinet (based on the 150-year-old “Pepper’s Ghost” optical illusion) was developed with the University of Nottingham Live, Experiential and Digital Diversification team to allow Xô Xinh to “perform” his soundtrack along with Dust & Metal. This distinct screening method mirrors the combination of archive film and new footage in Dust & Metal, demonstrating a new adaptation of old technology for a different live experience. This mode of presentation was also created as an alternative method of presenting a live score in reaction to the climate emergency, reducing the need for Xô to travel, and was performed at the Watershed, Bristol, and Broadway, Nottingham in 2024 after Xô had returned to San Francisco.

Feedback from screenings has included comments on how the film has inspired audiences unfamiliar with the cinema of Vietnam to view further titles from this rich seam of film heritage, with others being inspired to visit Vietnam itself. Screenings have also sparked discussions about access to archives in Vietnam and how more films might be shared and programmed more widely. Audiences in Vietnam have expressed how the film has encouraged them to connect, or reconnect, with their country’s film heritage, and has provoked intergenerational discussion with older viewers having a different reading of, and contextual knowledge, of the films to younger generations. Other audience members have been in contact to express how the film has sparked a new way of looking at the history of bicycles and motorbikes, and their importance in the fabric of past and present Vietnamese life.

The British Council has since supported my short film, provisionally titled Intermediate Copy, which specifically looks at the behind-the-scenes workings of the Vietnam Film Institute and its archives. The work will be shot on film, with a film crew and equipment sourced in Vietnam. The film rushes and completed film will be donated to the VFI, with the institute digitising the film rushes via their on-site 2K suite. TPD is assisting with the production of this new work that will act as a codex to Dust & Metal and will address the labour involved in archiving film at the VFI, the complexities of archives, the politics of access, why we archive, and what we can learn from archiving.

Dust & Metal is my bức thư tình to Vietnam and the generous people whom I befriended during production.[11] It has been an ambitious project, with collaboration fundamental for the research, and was only made possible due to the generous partnerships formed. I would like to thank them all for sharing their histories and experiences and for helping me to see Vietnam anew.

Notes

[1] Extracts from Việt Linh’s The Travelling Circus are included in Dust & Metal. The film was included as one of three classic Vietnamese films in the 2024 Star Nhà Ease: Vietnamese Cinema UK tour curated by me, Cường Minh Bá Phạm, and Tuyet Van Huynh (Live Cinema UK and Huỳnh). This programme included the classic Vietnamese titles Em bé Hà Nội (Little Girl of Hanoi, Hải Ninh, 1974), and Bao giờ đến tháng Mười (When the Tenth Month Comes,Đặng Nhật Minh, 1984), that also feature in Dust & Metal, plus the 2015 feature documentary Finding Phong byPhương Thảo and Swann Dubus (2022), and a programme of contemporary short films by Vietnamese filmmakers and the diaspora.

[2] The limited scope of this article does not permit a full history of international access to Vietnamese cinema but, for context, the first public screening of a Vietnamese drama feature film in the US was in 1985 at the Hawaii International Film Festival. The film was Đặng Nhật Minh’s seminal 1984 Bao giờ đến tháng Mười (When the Tenth Month Comes), excerpts of which are included in Dust & Metal. The festival took place a year before Đổi Mới (which translates as “renovation” or “innovation”), when economic reforms took place in Vietnam to create a socialist-oriented free market economy on the lines of Glasnost. Vietnamese cinema began to be shared beyond former Eastern Bloc countries during this period. At the 1987 edition of the Hawaii International Film Festival, “The Vietnam Project” was conceived to introduce the Vietnam film industry and film heritage to America. The project was led by a consortium of American film institutions alongside the General Director of the Vietnam Cinema Department, Nguyễn Thu. Subsequently, the Campaign for Vietnamese Cinema in England was led by Neil Gibson and Leslie Gould in the UK and in 1991 Gibson directed the Channel 4 documentary Vietnam Cinema tracing the history and development of Vietnamese filmmaking from the August Revolution in 1945 up until 1990. A significant step in introducing classic Vietnamese films to a wider public in Vietnam were the DVDs produced by Gerald Harman, filmmaker and founder of Southeast Asia’s first art house cinema, Hanoi Cinématheque (now closed), and a collection released by Phuong Nam Film.

[3] In 1945, Vietnam’s Ministry of Information and Propaganda Film Department was formed. On 15 March 1953, Ho Chi Minh signed Decree 147/SL to establish the Vietnam State Enterprise for Photography and Motion Pictures. The Vietnam Cinema Department was founded in 1956, with The News and Documentary Film Studios (now the National Documentary and Scientific Film Studio) opening in June the same year. Other studios consisted of The Hanoi Film Studio, the Vietnam Feature Film Company (later becoming The Vietnam Film Studio VFS), and an animation studio. Additional studios included the People’s Police Film Studio (part of the Ministry of Public Security), and the People’s Army Film Studio (part of the Ministry of Defence), who also has the second largest film archive in Vietnam after the VFI. Filmmaking in Vietnam was initially a government enterprise with studios managed by film directors and artists. Documentary has traditionally been an important form of filmmaking in Vietnam, with more documentaries produced in the cinema departments than any other genre. Many of the classic feature film directors started out in documentary with their location shooting experience benefitting the drama films they went on to make. In 1979, the Vietnam Film Documentation Institute (now the Vietnam Film Institute) was founded and administered under the umbrella of government agency, the Ministry of Culture. The Film Institute contains 44,570 film reels of various formats, and 20,000 works on tape, and has been affiliated to the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) since 1987. The Centre for Film Studies and Film Archiving is a HCMC subsidiary of the VFI and was founded in 1976 following the reunification of Vietnam. This archive holds approximately 38,000 film reels. The independent film sector in Vietnam is relatively young as it was only in 2002 that independent film studios were permitted to exist outside the government film studio structure. Since the 2010s, Vietnamese cinema has been gaining more recognition internationally with recent films screened and honoured with awards at prestigious film festivals such as Cannes, Berlinale, and IDFA. The first Vietnam Film Festival (now Hanoi International Film Festival – HANIFF) took place in 1970 and since then it was run biennially by the Vietnamese Ministry of Culture. With recent revisions to Vietnam Cinema laws, film festivals are now able to be independently organised in the regions. Dust & Metal screened at the first Danang Asian Film Festival (DANAFF) in May 2023, organised regionally by the Vietnam Film Development Association (VFDA established in 2019). 2024 saw the first Ho Chi Minh City International Film Festival (HIFF).

[4] The approach to Dust & Metal draws on methodologies I developed for my poetic live cinema feature film Asunder (2016), funded by 14–18 NOW in the UK to commemorate the centenary of the First World War. This film integrated sequences of newly shot footage in addition to film from four different archives, three based in the UK (the British Film Institute, the Imperial War Museum, and the Northeast Film Archive), in addition to the Swedish Film Institute. The script incorporated oral histories researched in archives. The film premiered marked the centenary of the Battle of the Somme in 2016 screening with a live score performed by Field Music, Warm Digits, The Cornshed Sisters, and The Royal Northern Sinfonia.

[5] The script is narrated by the well-known Vietnamese actress Lan Hương Nguyễn who famously featured in director Đặng Nhật Minh’s film Mùa ổi (The Season of Guavas, 2000) one of the few Vietnamese films that has had international distribution, extracts of which are included in Dust & Metal. The recording of the script took place in a studio in Hanoi which I directed remotely as pandemic travel restrictions meant I was unable to be there in person.

[6] “Histories from below” are narrative accounts of historical events from the perspective of working people and outsiders rather than those of the establishment. Coined by Georges Lefebvre in 1932, the phrase was later popularised by the History Workshop movement in 1960s Britain, and by E. P. Thompson in his 1966 essay “History from Below”. The term is synonymous with “people’s history” and “social history”.

[7] Trần Văn Thủy (b.1940) has directed countless documentary films. Extracts from his films Hà Nội Trong Mắt Ai (Hanoi in Whose Eyes, 1983) and Chuyện Tử Tế (The Story of Kindness, 1987) feature in Dust & Metal. Both films were banned for many years in Vietnam for their criticism of the regime. In Whose Eyes: The Memoir of a Vietnamese Filmmaker in War and Peace byTrần Văn Thủy and Lê Thanh Dũng was also consulted for the research.

[8] “Li” is the Chinese mile, which equals approximately 1/3 English mile, or ½ kilometre.

[9] A list of public screenings of Dust & Metal can be found at the film’s official webpage.

[10] This track is by Vietnamese group BAN AVT (BAN Kích Động Nhạc AVT), founded in 1958 in Saigon by a trio of musicians Anh Linh (guitar), Van Son (drums), and Tuan Dang (double bass), civil servants and noncommissioned officers of the Vietnam Arts Battalion, Psychological Warfare Department. The music had satirical lyrics over traditional instrumentation. On the reunification of Vietnam on 30 April 1975, the band disbanded. Anh Linh was imprisoned, Van Son died whilst fleeing, Tuan Dang stayed in HCMC, and later member Lu Lien fled to the US. In 1976, the AVT Overseas Satirical Trio was formed in the US consisting of different members up until 2008 when it was disbanded.

[11] Bức thư tình is Vietnamese for “love letter”.

References

1. “Archive.” Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2025, OED Online. Accessed 22 July 2025.

2. Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Future. The Viking Press, 1961.

3. Asunder. Directed by Esther Johnson, Blanche Pictures, 2016.

4. Bao giờ đến tháng Mười [When the Tenth Month Comes]. Directed by Đặng Nhật Minh, Vietnam Feature Film Studio, 1984.

5. Bly, Nelly. “Champion of Her Sex.” New York Sunday World, 2 Feb. 1896, p. 10.

6. “British Council Announces International Creative Partnerships Supported by New Digital Collaboration Fund.” British Council, 14 Jan. 2021, www.britishcouncil.org/about/press/british-council-announces-international-creative-partnerships-supported-new-digital.

7. Chen, Nancy N. “‘Speaking Nearby’: A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh‑ha.” Visual Anthropology Review, vol. 8, no. 1, Mar. 1992, pp. 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1525/var.1992.8.1.82.

8. Chuyện tử tế [The Story of Kindness]. Directed by Trần Văn Thủy, National Documentary and Scientific Film Studio, 1987.

9. Dust & Metal [Cát bụi & Kim loại]. Directed, written, and edited by Esther Johnson, Live Cinema UK and Blanche Pictures, 2022.

10. “Dust & Metal”. Blanche Pictures, 2022, https://blanchepictures.com/dust-and-metal/. Accessed 22 July 2025.

11. Em bé Hà Nội [The Little Girl of Hanoi]. Directed by Hải Ninh, Vietnam Feature Film Studio, 1974.

12. “Em Tập Lái Vespa.” Ban AVT, 1960s, Nhạc Của Tui, www.nhaccuatui.com/bai-hat/em-tap-lai-vespa-ban-avt.T79SG24_DY.html.

13. Faulkner, William. Requiem for a Nun. Random House, 1951.

14. Finding Phong. Directed by Phương Thảo and Swann Dubus, 2022.

15. Gánh xiếc rong [Travelling Circus]. Directed by Việt Linh, Giải Phóng Film Studio, 1988.

16. Hà Nội trong mắt ai [Hanoi in Whose Eyes]. Directed by Trần Văn Thủy, National Documentary and Scientific Film Studio, 1983.

17. Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate. US Government Printing Office, 2 Feb. 1967, www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-90shrg74687/pdf/CHRG-90shrg74687.pdf.18. Ho Chi Minh. “Long Detention Without Interrogation.” Prison Diary. Translated by Đặng Thế Bình, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1972, p. 107.

19. Huyen, N. “Vietnam Leads the World in Motorcycle Usage with Over 77 Million Registered.” VietnamNet, 5 Nov. 2024, https://vietnamnet.vn/en/vietnam-leads-the-world-in-motorcycle-usage-with-over-77-million-registered-2338732.html.

20. Lefebvre, Georges. La grande peur de 1789. Librairie Armand Colin, 1932.

21. Live Cinema UK and Tuyết Vân Huỳnh. “Star Nhà Ease: Vietnamese Cinema.” Live Cinema UK, 19 Mar. 2024, https://livecinemauk.com/work/live-cinema-star-nha-ease-events/.

22. Minh-ha, Trinh T. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Indiana UP, 1989.

23. Minh-ha, Trinh T., and Lucie Kim-Chi Mercier. “Interview: Forgetting Vietnam.” Radical Philosophy 203, Dec. 2018, pp. 78–89, https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/forgetting-vietnam.

24. Mùa ổi [The Season of Guavas]. Directed by Đặng Nhật Minh, Vietnam Feature Film Studio (Youth Film Studio), 2000.

25. Nguyễn, Nhung. Sound Awakener. 2025, https://soundawakener.com. Accessed 29 May 2025.

26. Salisbury, Harrison E. Harrison E. Salisbury’s Trip to North Vietnam: Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate; 90th Congress, 1st Session. With Harrison E. Salisbury, February 2, 1967. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967, www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-90shrg74687/pdf/CHRG-90shrg74687.pdf.

27. “The Bicycle and the Incredible Records during the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.” Vietnam Evasion, en.vietnamevasion.com/bicycle-incredible-records-battle-dien-bien-phu. Accessed 22 July 2025.

28. Thompson, E. P. “History from Below.” The Times Literary Supplement, 7 Apr. 1966, pp. 279–80.

29. Trần Văn Thủy and Lê Thanh Dũng. In Whose Eyes: The Memoir of a Vietnamese Filmmaker in War and Peace. U of Massachusetts P, 2016.

30. Trịnh, Công Sơn. “Cát Bụi” [“Sand and Dust”]. Diễm Xưa Productions, 1971.

31. Vietnam Cinema. Directed and produced by Neil Gibson, 1991, Channel 4.

32. “Vietnam Population (Live).” Worldometer, 2025, www.worldometers.info/world-population/vietnam-population. Accessed 22 July 2025.

Suggested CitationJohnson, Esther. “Speaking With: Histories of Vietnam Explored Through Archive Film.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 29–30, 2025, pp. 263–280. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.2930.16

Esther Johnson (MA, Royal College of Art), artist and filmmaker, creates poetic portraits blending artist moving image and documentary to explore alternative social histories and marginal worlds. The repositioning of archival material and oral histories is explored to examine intangible cultural heritage and the link between memory and storytelling. Her films have screened in festivals and galleries in over forty countries and have been broadcast on BBC, Channel 4, and BFI Player. A former recipient of the Philip Leverhulme Research Prize, she is Professor of Film and Media Arts at Sheffield Hallam University’s Art, Design and Media Research Centre. Website: blanchepictures.com