The Tales of New Orleans after Katrina: the Interstices of Fact and Fiction in Treme

Delphine Letort

While the apocalyptic events that followed Hurricane Katrina’s sweep over New Orleans have given rise to an abundant fiction and nonfiction literature, few directors have considered adapting these stories to the screen or have used Katrina as a narrative prompt. [1] Although New Orleans’ motion picture industry has thrived and contributed to the city’s recovery by investing large sums of money into its economy over the past few years, with filmmakers taking advantage of the 2002 Louisiana Motion Picture Incentive Act, [2] the renown and appeal of the “Hollywood South” as a shooting location have not extended beyond the cultural archetypes and local settings that are constitutive of its filmic mythology: from Jezebel (William Wyler, 1938) to The Princess and the Frog (Ron Clements and John Musker, 2009), films have shaped our perceptions of New Orleans as “The Big Easy”, celebrating the “elegance of Creoles, the skill of jazzmen, the seductiveness of courtesans, the joy of Mardi Gras makers, the romance and exoticism of the French Quarter” (Stanonis 4). The traces of Katrina hardly feature in any film—one may have spotted fleeting shots of the wind-battered houses in Bertrand Tavernier’s In the Electric Mist (2009) or gazed at the derelict landscape of the Lower Ninth Ward in Michael Almereyda’s independently produced New Orleans Mon Amour (2008); however, most films eschew the race and class issues that were uncovered by media reporters as they ventured into the drowning city and discovered many African Americans trapped by the floods caused by the breach of the protective levees surrounding the city after Katrina wreaked havoc on the Gulf Coast, exposing to the world the state of poverty that exists in the shadow of New Orleans’ popular culture.

Produced by HBO, Treme (2010–) is a drama series set in post-Katrina New Orleans; created by David Simon and Eric Overmyer, it explores the psychological and material imprint of the storm on the lives of the New Orleanians who decided to settle back in the city only three months later. Although the title refers to Tremé, a gentrified quarter of New Orleans, the demographics of which have been predominantly black since the first half of the century (Crutcher 5), the series’ setting is not geographically restrained to historical Tremé. The television drama features a multiple narrative structure, developing several storylines at once, which allows the directors to draw a vivid portrait of New Orleans through a gallery of characters from all walks of life. The series thereby articulates the social distance between the characters, whose reconstruction efforts depend on where they live in the city: some have to struggle with the loss of all personal belongings having been washed away by the floods whereas others are confronted with the disruptions caused by missing infrastructures, including power shortage and failing contractors. Not only do most characters have to come to terms with traumatic memories, but they also have to face rising urban gang violence, which the series relates to cases of police misconduct. The series heightens the tension between the past, which was engulfed in the waters that overflowed the levees, and the uncertainties of the present. Although it delves into the rich cultural life of the parades and the jazz clubs, which invigorates the viewing experience, it also alternates silent intervals and musical sequences, adopting a slow rhythm that contrasts with conventional televisual flow (Polan 264). Moments of silence convey the invisible scars left by Katrina whereas the soundtrack prompts the viewer to immerse him- or herself in the musical folklore that attracts so many tourists to the French Quarter.

Narrative enigmas express the sense of trauma that pervades the present life of survivors: not only does Katrina denote the violent storm that hit the city and the political crisis that followed, making it difficult for individuals to imagine their own future in the rundown city, but it also signifies the rupture in the lives of many residents who could never go back to their wrecked homes and whose loved ones went missing. Narrative gaps signify the moment when the levees broke, causing the floods to erase all geographical landmarks and human artefacts, blurring the course of history, which now needs to be retraced. Integrated into the dynamics of the narrative, these enigmatic holes propel the investigative plot and politicise the discourse of the series. The series explicitly refers to specific events that hit the headlines, drawing entertainment from the dramatisation of everyday life in New Orleans. It offers critical insight into the politics of reconstruction by exploiting the tension between fact and fiction that pervades docudrama, integrating the musical heritage of the city into unfolding plotlines. [3] This article maps out the creative process behind Treme, specifically its first two seasons (2010, 2011), and how the series showcases the popular culture of the city, exploring the musical traditions born in the cradle of jazz, while minimising the importance of contemporary race and class issues. It analyses how the blending of factual and fictive elements to document the lived experience of post-Katrina New Orleans succeeds in calling attention to its rejuvenating music, while toning down the darker events unfolding in the city.

Docudramatising Post-Katrina New Orleans

The credits sequence of Treme epitomises the ambiguous line between fact and fiction, from which the series derives its dramatising power. The combination of soundtrack and imagery exemplifies the blend of fictional and documentary devices that characterises the series. Local musician John Boutté composed the theme tune, an upbeat jazz song, the lyrics of which relate the story of a “second line”—the moment when marchers and dancers join the traditional New Orleans funeral, turning the procession into a lively ceremony of celebration. [4] The music is used in counterpoint to a compilation of pictures, which juxtapose the colourful parades of the past with photographic evidence of destruction caused by the floods. The sequence highlights the signs of devastation as the camera pans through the ruined artefacts of family life, including family albums depicting an irretrievable past, thereby incorporating them in the diegesis of the series. The filmed waterlines testify to the ordeal individuals went through when trapped inside their house whereas photographs of mould-ravaged walls demonstrate the lack of progress since the storm. The camera intrudes on intimate memories by focusing on personal items, thereby heralding the series’ endeavours to grasp a subjective experience of life in New Orleans—instead of documenting a historical narrative.

Figure 1: Photomontage illustrating the credit sequence of Treme: the camera zooms in and out of stills showing the water-lines on the mould-ravaged walls that anchor the series in post-Katrina New Orleans. Credit: http://title-sequence.tumblr.com/

The use of fast cutting works against a nostalgic gaze; the disruption of the flow of images emphasises, as Deleuze observes with regard to the relationship between sound and image in modern cinema, that “interstices proliferate everywhere, in the visual image, in the sound image, between the sound image and the visual image” (175), hinting at all that remains unsaid about the individual experiences of Katrina. The prologue to the first episode foreshadows the rebirth of New Orleans through a second line that weaves through the streets of Tremé, thereby framing the televisual project as a story of resilience. The coloured archival footage inserted in the sequence depicts the spectacle of the parade, suggesting the series’ narrative will delve into community life through a focus on local traditions. Historian Richard Mizelle contends that the vibrant mise en scène of the parades symbolically offers “a way of understanding the psychological and physical pain of bereavement in New Orleans and provide[s] a model for the regeneration of the city” (Mizelle 70). The sequence suggests that Treme, rather than linger on the effect of destruction, will retrace the efforts of reconstruction.

While giving details of the cast and crew, the credits sequence interrupts the narrative flow of the episode, breaking the illusion of entertainment to recall the facts that gave birth to the project. As a docudrama, the series draws its realistic effect from the indexical relationship established between the diegetic universe of Treme and the real-life backdrop of New Orleans. The landscape of the city contributes to shaping the narrative structure of the drama insofar as it reflects the power relations within New Orleans, dividing it into various quarters according to class dynamics (see Morse). The characters’ stories pinpoint social differences between New Orleanians, whose Katrina experience was shaped by two entwined factors: their social status and their abode. Black and white, from uptown and from Tremé, the characters portray sociocultural diversity: Creighton Bernette’s (John Goodman) uptown house shows no mark of flooding, indicating a different social class to that denoted by the mould covering the walls inside Albert Lambreaux’s (Clarke Peters) wrecked house in Gentilly; Davis McAlary’s (Steve Zahn) neighbours are suggestive of the money invested to preserve the heritage value of the home they bought in historic Tremé, whereas LaDonna Batiste-Williams (Khandi Alexander) has been compelled to move to Baton Rouge to ensure the education of her children, even though she continues to run her roofless bar located in Central City; Delmond Lambreaux (Rob Brown) represents the cultural elite of the city, frequenting upmarket fashionable clubs, which do not reflect his father’s attachment to the Indian parade traditions. The series also contrasts the vibrant atmosphere in the tourist French quarter, the cultural life of which seems to thrive—as illustrated by Annie’s (Lucia Micarelli) successful career as a violinist, who climbs up the social ladder when invited to play on the stages of the most popular clubs—to the rundown landscape of the Lower Ninth Ward that breeds crime. The high level of violence that plagues the real city seeps into the narrative, allowing fact and fiction to feed off each other: unrepaired pot holes cause Davis McAlary’s car to break down, so that he is robbed of all his instruments on his drive uptown; Albert Lambreaux’s reconstruction efforts are threatened by the theft of his tools; sudden gunshots disrupt a night out in a club, instilling a sense of permanent danger and invisible threat.

The creators of the series cultivate the confusion between fact and fiction through a cast that includes amateur and professional actors. Phyllis Montana-Leblanc, whose face has become familiar since she bore witness to her experience as a Katrina survivor in Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006), plays the character of Desiree—a housewife whose complacency does not resonate with the resilience and activist commitment that characterise the woman in the nonfiction film. [5] New Orleans actor Wendell Pierce portrays a trombonist who strives to rival jazz musician Kermit Ruffins playing himself. The inclusion of local famous figures conveys the creators’ commitment to reconstructing an authentic picture of the city. “What brought this city back has been culture: an unyielding unwillingness to part with the living tradition that is life in New Orleans”, explains David Simon to justify the place given to concert rehearsals and Mardi Gras preparations in the show (qtd. in Beiser).

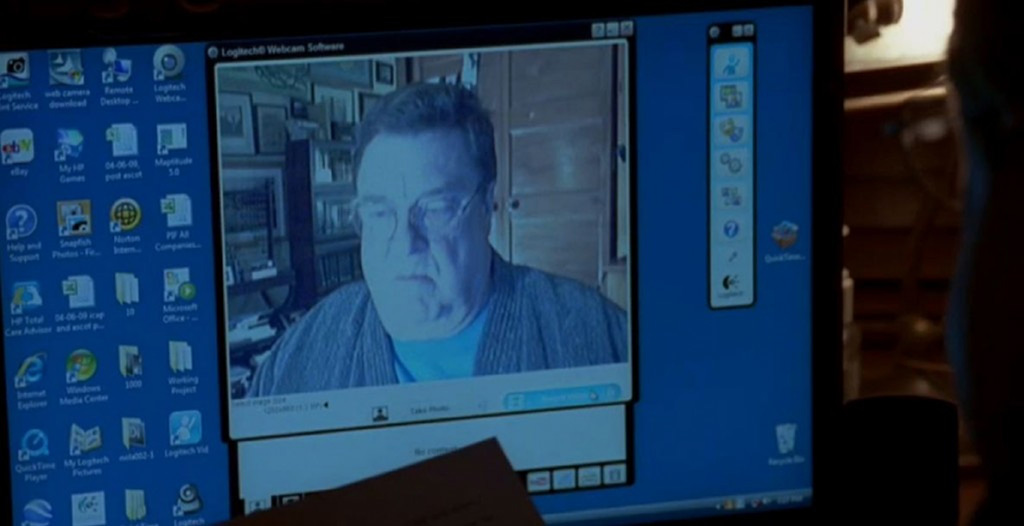

However, the series also resorts to fictional elements to reveal the invisible marks left by Katrina, including the psychological stress produced by the lack of information about the past (for example the incomplete story of LaDonna Batiste-Williams’s missing brother) and the existential anxiety caused by an uncertain future. Reconstruction is depicted as an added trauma as the characters are left on their own to cope with rebuilding their lives. The slow descent of Creighton Bernette into a state of acute suicidal depression is not visible to his family, although the scholar publicly vents his frustration on YouTube, gaining instant recognition among web users for giving voice to a collective anger. As signified in the opening credit sequence, the series uses music to alleviate the sense of psychological fatigue that underpins the narrative of material and personal reconstruction, suggesting the cultural diversity of the city offers a path of healing.

Figure 2: Creighton Bernette gains instant recognition by giving vent to his frustration and anger on YouTube. Treme Season 1 (David Simon and Eric Overmyer, 2010). HBO Home Video, 2011. Screenshot.

The series resorts to a mystery narrative strategy that, according to David Bordwell, makes use of narrative holes which can take several forms: “Temporal gaps are the most common sort, but any mystery or riddle narrative may also contain causal gaps” (54). Treme draws suspense from the narrative gaps that viewers expect to be resolved by the end of the series; the characters’ experience of Katrina prompts many questions as the series begins a few weeks after the storm has struck. The photographs of the tragedy that Toni Bernette examines while searching for LaDonna Batiste-Williams’s missing brother represent as many unsolved cases. The drama series is permeated by a sense of anxiety and loss, triggered by these gaps of information that pervade the narrative. The course of life was disrupted by Katrina, creating mysteries about past events and casting shadows over the future. The entwining plotlines dramatise the distance between the characters’ individual stories, prompting the viewers to relate and compare them. In this regard, Jane Feuer observes that soap operas interweave narrative strands to challenge the viewers into producing meaning: “Just when the reader’s interest has been secured by the characters and situation of one plot line, the text shifts perspective suddenly to another set of character and another plot strand” (Feuer 84). Treme uses these interstices to generate suspense and to broach political issues that subvert the status of the series as entertainment.

Subversive Spaces: Politics and Drama

The series’ emotional intensity comes from the close contact with death that the characters experienced during Katrina and the enduring threat posed by the ensuing high rate of crime. New Orleans is indeed depicted as a crime-ridden city, whose recovery is explicitly endangered by random offenses that go unpunished: LaDonna Batiste-Williams is raped after closing her bar and later recognises her attacker, who had been released from jail by mistake; Harley Watt (Steve Earle) is shot during a holdup while walking down the street; Sonny’s (Michiel Huisman) piano and money are stolen from him when street busking. While during the first season of Treme the killings involve characters unknown to the audience, by the end of the second season characters whose faces have become familiar are murdered, allowing the spectator to fully identify with the pain that shatters the victims’ friends and loved ones.

Incidents of violence serve to describe the inability of the police to maintain law and order, sustaining a sense of tension throughout the series. The death, which also took place in real life, of Dinerral “Dick” Shavers, a drum player in the Hot 8 Brass Band, who was shot in the back when driving through Tremé at night, produces an emotional shock that reverberates through Treme. Although the raw emotion caused by his death is captured by reenacting his funeral with actual members of his family, the drama series fails to provide an in-depth analysis of New Orleans’ catastrophic criminal record. Crimes are used to create narrative twists and reversals in the episodes of the series, relating the high level of crime to corruption and inefficiency in the police force: LaDonna Batiste-Williams fails to obtain a positive response when she calls 911 fearing for her life after she spots two men outside her bar; Davis McAlary criticises the slow arrival of the police when he discovers Jannette Desautel’s (Kim Dickens) house is being burgled; a random shooting disrupts a second-line parade, causing the death of an innocent woman; Toni Bernette’s (Melissa Leo) investigation into pending cases uncovers several misdemeanours among police officers; the death of Joey Abreu, whose decomposed body is found after Katrina in a store that was looted, gives rise to several stories that echo the confusion around the notorious Danziger Bridge killing. [6] By researching the case of Abreu, Toni exposes the lack of ethics among officers of the New Orleans Police Department; however, the series avoids addressing the racist killing by making Abreu a white character, in contrast to the actual events at Danziger Bridge.

The television series does not espouse a militant streak although it conveys a critical stance embodied by Professor Creighton Bernette as he challenges the official version of the Katrina catastrophe, which he depicts as “a man-made disaster”, in front of television cameras. He loses his composure when questioned about why New Orleans should be rescued from the waters by federal money, expressing both local and national patriotism. Bernette’s celebrity status references the popularity of historians John Barry and Douglas Brinkley, the real-life counterparts of the character. Both were invited to share their expert knowledge through the talking-head interviews in Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts and its sequel If God is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise (2010), providing a scholarly analysis of the race and class debate underpinning the city’s present and past reconstructions. Scholars have identified that reconstruction repeated a historical discriminatory pattern: not only was the rate of destruction lower in white upscale areas than in predominantly African American neighbourhoods, but reconstruction was slow to reach all the quarters of the city. The enforced policies of demolition strongly discouraged low-income residents from going back to New Orleans. [7]

Brinkley’s book The Great Deluge testifies to his professional and personal engagement with the issues raised by Katrina. The book is full of emotional overtones, which Creighton Bernette’s raw statements echo in Treme. The character’s impulse to speak resonates with Brinkley’s confession that he felt writing was a duty for him:

That writing for a Katrina survivor like myself was not about a hit book, but a calling. Having worked the rescue boats in devastated New Orleans, wondering when FEMA and the Red Cross would arrive with help, witnessing NOLA police brutality, I was duty bound to speak up. A nurse can administer insulin and a fireman can put out a blaze. I am a writer. My tools are pen and paper. I survived Katrina by good luck and economic privilege. To have not written about what I had witnessed would’ve been to betray New Orleans, Bay St. Louis (where I had a home along the Jordan River that was obliterated) and myself. The Great Deluge was one historian’s heartfelt response to the worst hurricane America has endured.

John Barry wrote at length about The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which is the subject of a novel that Creighton Bernette is writing in the drama. While Bernette obviously voices the most provocative and subversive comments in Treme, his death at the end of Season One deprives the series of an informed political view. His YouTube recordings suggest similarities between Bernette’s stout figure and Michael Moore’s film persona, both posing as icons of political engagement in their nonfiction films. The embedded Internet sequences showing either Creighton or his daughter Sofia (India Ennenga), who honours her father’s legacy by posting her own videos, draw attention to the characters’ performative role within the drama.

The use of docudrama emphasises the political subtext of the series by enhancing the performative aspect inherent in televised public statements. Film theorist Stephen N. Lipkin argues that “docudrama foregrounds what it represents as performance, however it is a performance of the actual” (2). When Albert Lambreaux cuts through the wire netting set up around the Saint Bernard housing projects he is illegally about to enter, he tells his friends to warn the media of his action: as the visible cameras start rolling and the lighting is switched on, the technical backdrop breaks with the make-believe illusion of the series, emphasising instead its artificial reconstruction. The series does not eschew a self-reflexive dimension, which emphasises the use of docudrama as a “catalyst for social awareness” (Hoffer and Nelson 21). The sequence discussed here points to the media’s framing of the occupation in the housing projects as a newsflash story, which has little consequence apart from the brutal arrest of Lambreaux. The scene shows several policemen hitting the unarmed man in the dark of night, hinting at the racist beatings perpetrated by uniformed officers in the Rodney King video. [8] Although the series highlights references to real events, which it intertwines with fictional recreations, it does not dwell on the political debate that led to the decision to tear down the housing projects. In Spike Lee’s If God Is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise, attorney Monique Harden interpreted this act as a sign of racial discrimination, arguing that the demolition programme was equivalent to “ethnic cleansing”. While Treme dramatises the problems posed by reconstruction, it does not offer an analysis of the situation, adopting instead a race-blind approach to New Orleans society.

The name of Mayor Ray Nagin is not mentioned until the beginning of the second season; his face appears on diegetic television screens, expressing the distance between the local authorities and the concerns of ordinary citizens and echoing the televised intervention of George W. Bush from Jackson Square, which Creighton Bernette watches again on his computer, pondering the failures of the president to deliver on his promises. Although Treme illustrates the neoliberal underpinnings of reconstruction through the portrayal of opportunist contractors like Nelson Hidalgo (Jon Seda), who negotiates Federal Emergency Management Agency contracts for his Texan firm and increases his profits by exploiting illegal Brazilian workers, the series does not suggest any alternative path of action or resistance. Albert Lambreaux seems to be an isolated figure when he breaks into the fenced-off Saint Bernard housing projects in order to occupy the buildings doomed to demolition. His intrigued gaze at the personal items left in haste by former residents highlights the lack of water damage, prompting questions as to the political reasons behind the demolition.

Even though Treme is not devoid of political undertones, particularly in its depiction of the cases of injustice that mar the narrative of reconstruction in New Orleans, the series favours humour as a narrative device. When Davis McAlary runs for mayor with a campaign that puts forth an ironic “Pot for Potholes” slogan, he both participates in and denounces the theatrics of politics in New Orleans. The musician assumes an explicitly dissenting opinion when creating a band that plays what he dubs a politically committed musical gumbo—including his provocative hit song “Shame Shame Shame”. However, his musical creativity becomes the basis for entertaining episodes that downplay the gravity of all his political speeches, turning him instead into a comical character that cannot be taken seriously.

Treme focuses on mainstream characters that made it back to New Orleans despite material inconveniences that challenge their means of survival (power cuts, water-ravaged homes, roof damage, among others). Most episodes showcase local curiosities such as clubs and streets that denote the cultural and musical backdrop of the city in which plotlines and storylines unfold. The series foregrounds local folklore when portraying Mardi Gras festivities. Although Indian Chief Albert Lambreaux spends the first parade since Katrina in jail after breaking into the housing projects, the individualistic dimension of his commitment compromises its political underpinning. Rather than extol an act of community resistance, the series underlines individual bravery insofar as his act does not support a collective agenda. Albert Lambreaux expresses more concern about the costumes he wishes to finish sewing in time for Mardi Gras to make the tradition endure than about organising his life as an activist. He fights for preserving the Indian cultural heritage of the city, but he does not strive to mobilise the community into saving the Saint Bernard housing projects.

Figure 3: While Albert Lambreaux stands out as an activist fighting for housing rights, local traditions come first; his concern for sewing Indian costumes in time for Mardi Gras undermines the portrayal of his activist commitment. Treme Season 1. HBO Home Video, 2011. Screenshot.

The festivities of Mardi Gras are incorporated into the spectacle of the series, which however provides little historical background to the tradition it represents. Treme does not delve into the controversies that have arisen in the gentrified quarter of Tremé where upper-middle-class newcomers complain about the disturbing noise produced by the parades and the jazz clubs. Historian Michael E. Crutcher makes it clear that gentrification transforms the social landscape of the city because the movement to renovate or preserve historic housing removes “affordable housing stock beyond the means of the neighbourhood’s working-class and poor African American residents” (97). [9] The new residents’ “push to make the neighbourhood safe, orderly and well kept becomes problematic … when those efforts collide with the area’s musical and parading traditions” (103). In Treme, the race and class issues that emerge with gentrification are transformed into neighbourly disputes between Davis McAlary and the gay couple living next door. The cultural gap between the New Orleanians turns into entertaining musical contests, which downplay the community impact of gentrification. Treme’s social landscape does not reflect the city’s economic and racial history, for the series personalises issues such as racism following the Hollywood formula (Bordwell, Staiger and Thompson 55). This approach undermines its subversive potential insofar as the political debate is framed within personal, individual concerns.

From Docudrama to Melodrama

Treme crafts fiction out of the city’s musical history by integrating the live performances of Trombone Shorty Andrews, pianist Tom McDermott and trumpeter Kermit Ruffins. The musical sequences provide entertaining pauses in the narrative, allowing viewers to indulge in the pleasure of watching live performances. Much of the second season enhances the entertainment objective of the series by highlighting the creativity of musical artists who channel their anger into composing new music: Antoine Batiste and DJ Davis establish their own bands whereas Annie learns how to write songs. Not only is music woven into the characters’ everyday life, thus making the role of music central to the series, but it also gives sense to their remaining in New Orleans. Music is the cement that unifies the series beyond the interstices of image and sound while creating a cultural bond among the residents of Tremé, which extends to the community of viewers.

Figure 4: Music is part of the entertaining features of the series, drawing attention to local attractions —including bars and clubs used as authentic settings. Musical compositions and interpretations unify the whole series, enticing the viewer into watching the show. Treme Season 2 (David Simon and Eric Overmyer, 2011). HBO Home Video, 2012. Screenshot. DVD.

The characters of Treme embody the cultural elite of New Orleans and portray the mainstream society of the city according to a colour-blind perspective: Antoine Batiste finds it hard to earn a living from playing jazz, but his girlfriend is a teacher in the reopened charter school; chef Janette Desautel runs into debts to keep her restaurant open and moves to New York to work, but she is invited to cook her own recipes in a New Orleans restaurant at the end of Season Two; Creighton Bernette’s scholarly work makes him valuable for publishers whereas Toni is renowned as a lawyer; and LaDonna Batiste-Williams runs her own bar with the help of a few employees. While all the characters must face up to the difficulties of reconstruction, they articulate the point of view of mainstream society. Such nonfiction films as Luisa Dantas’s Land of Opportunity (2012–2011) and Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts depict a darker situation by giving voice to poor New Orleanians, who feel they have not been given a chance to settle back in the city because official reconstruction plans favour some areas while neglecting others—including the historic black quarter in the Lower Ninth Ward. The nonfiction films investigate the racially segregated past of the city, which does not seem to bear on the present of Treme. No voice is given to the people who were evacuated and unable to return to New Orleans even though the traces of their absence darken the tone of the series and generate suspense by metaphorically representing narrative gaps to be filled. A case in point is the enigmatic story behind the death of Daymo (LaDonna Batiste-Williams’s brother), who has been missing since Katrina.

Narrative interstices create suspense in Treme whereas characterisation introduces elements that foreground what Brooks describes as the features of the melodramatic imagination: “indulgence of strong emotionalism; moral polarisation and schematisation; extreme states of being, situations, action; overt villainy, persecution of the good and final reward of virtue; inflated and extravagant expression; dark plottings, suspense, breathtaking peripety” (4). The series derives dramatic power from stereotypical situations, thus illustrating the enduring power of race and gender stereotypes. Love stories provide basic plots in the series, which devotes more than a few scenes to Sonny and Annie, the young musicians whose idyll progressively dissolves on the streets of New Orleans. Antoine Batiste’s portrayal as an unfaithful and flirtatious husband underlines his stereotypical hypersexual black masculinity, whereas LaDonna Batiste-Williams’s provocative femininity symbolically leads to her rape which, even though committed by two black men, resonates with the sexual history of female slavery. The censorship-free production context, permitted by distribution on a pay station, allows the directors of the series to include a few sex scenes that spice up the storyline. Like other HBO programmes that use nudity, violence and vulgarity to increase viewing figures (Zimmerman 49), Treme invites a voyeuristic gaze at the black bodies of the women Antoine Batiste strips naked in front of the camera eye. The series does not completely challenge the race and gender ideological framework it spotlights, making use of common stereotypes to address sexual issues.

The police beating of Indian Chief Albert Lambreaux further reenacts the racial dynamics of melodrama that, according to Linda Williams, “focuses on victim-heroes and on recognising their virtue. Recognition of virtue orchestrates the moral legibility that is key to melodrama’s function” (29). The focus on crime dramatises the issue of violent death in New Orleans, but it does not urge the viewer to question the nature and the roots of violence: the series depicts stereotypical characters such as good cops and bad cops, victims and criminals, reproducing some of the media bias on black crime and eschewing questions related to the widespread availability of guns and the desensitisation process at work in the city. The discovery of Daymo’s corpse in the city’s makeshift morgue (consisting of a long line of refrigeration trucks) gives rise to a new mystery about a case of mistaken identity. Such subplots are used as a device to propel the narrative forward instead of interrogating the urban fabric of crime. John Fiske points to the limits of popular drama when observing:

Popular texts may be progressive in that they can encourage the production of meanings that work to change or destabilize the social order, but they can never be radical in the sense that they can never oppose head on or overthrow that order. Popular experience is always formed within structures of dominance. … Popular meaning and pleasure are never free of the forces that produce subordination, indeed, their essence lies in their ability to oppose, resist, evade, or offend these forces. (133–4)

Although Treme appears to be an innovative series that tackles sensitive subjects, it exploits the culturally rich backdrop of New Orleans in an attempt to attract the tourist viewer to the show. The series foregrounds the spectacle of music and parade traditions, presenting a conventional tourist-style view of the city. The tension between docudrama and melodrama emphasises the focus on individual experiences rather than allowing a community project to emerge. The characters endeavour to reconstruct their life from remnants, highlighting the plight and resilience of various individuals. By the end of Season Two, the chance to start a new life is suggested by Janette Desautel’s return to New Orleans and the Batiste family’s move into a new house. Reconstruction in post-Katrina New Orleans was however fraught with conflicts between the community and the local authorities, which have little bearing on the imagined city of Treme.

Conclusion

As daring as Treme might be when broaching taboo issues, including the increased rate of suicide attempts in the aftermath of Katrina, testifying to the series’ commitment to conveying an authentic view of New Orleans, the tension between fact and fiction limits the scope of its political discourse. Treme exploits the nostalgia of local jazz funerals and eschews race and class issues, laying stress on the city’s unique web of cultural traditions instead. Docudrama combines with melodrama to enhance the entertaining features of the series, bringing forth stories of energising musical creation that overshadow the socioeconomic backdrop of New Orleans. The characters transcend the constraints of their environment, achieving self-accomplishment through musical creativity, which the series celebrates as a path of healing. The drama series promotes the exotic entertainment dimension of New Orleans’ city life, which does not fully convey its historical background. While socioeconomic differences structure the characters’ experience of reconstruction, the racial underpinning of local history vanishes in the jazz clubs populated by racially mixed crowds.

Although the series may use post-Katrina New Orleans as a backdrop to its narrative, it does not portray the full impact of reconstruction. While Treme points out that the return to normality is too slow to permit business to thrive, it does not highlight the plight of displaced New Orleanians who were not welcomed back to the city. Even though the series is shot on location, thereby testifying to a desire for authenticity on the part of the creator and producer David Simon, the leading characters of Treme do not embody the diversity of experience in New Orleans. The series does not express the feeling of exclusion voiced by many African American New Orleanians in Spike Lee’s documentaries, questioning the racial underpinning of reconstruction policies that changed the sociological composition of the city. The political dimension of Treme is undermined by the melodramatic mode, which quells collective anger by focusing on the plight of individuals. While the series enhances the cultural role of jazz music and dance traditions, which have survived as icons of resilience in New Orleans, it turns such rituals into commodities that sell both on the streets of New Orleans and on HBO.

Notes

[1] See, among others: Ward; Jameson; Coutta; Piazza; Burke; Pollard and Eggers.

[2] Scott Jordan Harris explains that the act can be broken down into two parts: “the Investor Tax Credit and the Labor Tax Credit. The first gives a 30 per cent tax credit on film production costs, while the second gives a 5 per cent tax credit on wages paid to Louisiana residents during film production” (84).

[3] Stephen N. Lipkin argues that “docudrama works as a mode of presentation in its fusion of documentary material (its ‘actual’ subject matter), and the structures and strategies of classic Hollywood narrative form, including character development, conflict, and closure” (Lipkin 2).

[4] “Hangin’ in the Treme/Watchin’ people sashay/Past my steps/By my porch/In front of my door//Church bells are ringin’/Choirs are singing/While the preachers groan/And the sisters moan/In a blessed tone//Down in the treme/Just me and my baby/We’re all going crazy/Buck jumpin’ and having fun//Trumpet bells ringing/Bass drum is swinging/As the trombone groans/And the big horn moans/And there’s a saxophone”.

[5] Spike Lee’s documentary series (When The Levees Broke: A Requiem In Four Acts and If God Is Willing And Da Creek Don’t Rise) investigate post-Katrina New Orleans through the stories told by present and former residents, thus drawing a sociological portrait of the city and addressing an array of issues raised by reconstruction. The two parts of the series present the film’s participants through their personal and professional connections to the city: be they black or white, rich or poor, doctors or policemen, residents from uptown or from the housing projects, they look back at their experience of the 2005 hurricane and assess its impact on their life. The episodes are dialectically constructed to posit a study of New Orleans social fabric and racial inequalities as they are blatantly exposed by the accounts of witnesses and experts.

[6] Henry Glover was shot when attempting to cross the Danziger Bridge during Katrina; the police officers involved in the case let him bleed to death before they burnt his body in his car. The death of Henry Glover was viewed as a blatant example of racist violence perpetrated by the police, fuelling distrust among African American citizens.

[7] “Extreme events reveal the extreme difference in the way we live and die, cope and rebuild. Historical reconstruction experiences, as well as New Orleans history, consistently report on inequitable patterns of social vulnerability and outcomes of reconstruction. New Orleans was a predominantly black city (68%), and media coverage would easily suggest that poor African Americans were the prime victims of the flood, the botched evacuation, and the inadequate shelter. … There were clearer racial and class differences in the ability to cope with the flood, to return and to rebuild” (Kates, Colten, Laska, and Leatherman).

[8] African American motorist Rodney King was arrested for speeding on 3 March 1991. Four Los Angeles police officers beat him without knowing that the whole scene was being videotaped. Although the video was produced as proof of police abuse in the ensuing trial, the four men implicated were acquitted.

[9] The author considers the cultural consequences of gentrification: “The effects of gentrification are not restricted to displacement. The process also involves the neighborhood character changing from one familiar to long-term residents to one that matches the aesthetics—in the case of Tremé, French Quarter aesthetics—of the newcomers. Although these changes vary from neighborhood to neighborhood, they often involve a regulation of social spaces, public and private, informal and designated. Examples include newcomers who protest residents’ practices of placing house furniture on front porches and congregating outside” (107).

References

1. Almereyda, Michael, dir. New Orleans Mon Amour. Voodoo Production Services, 2008. Film.

2. Barry, John M. Rising Tide, The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How it Changed America. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperback, 1998. Print

3. Beiser, Vincent. “An Interview with David Simon”. The Progressive. March 2011. <http://progressive.org/david_simon_interview.html> Web. 1 Feb. 2013.

4. Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison, WI: U of Wisconsin P, 1985. Print.

5. Bordwell, David, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. London: Routledge, 1985. Print.

6. Brinkley, Douglas. Message to the author. 9 Feb. 2012. E-mail.

7. Brooks, Peter. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama and the Mode of Excess. 1976. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

8. Burke, James Lee. The Tin Roof Blowdown: A Dave Robicheaux Novel. London : Orion Books, 2007. Print.

9. Bush, George W. “Address of the President to the Nation (Katrina Speech)”. 15 Sept. 2005. <http://thinkprogress.org/politics/2005/09/15/1870/katrina-speech-text/?mobile=nc>. Web. 6 July 2013.

10. Clement, Ron and John Musker,dir. The Princess and the Frog. Walt Disney Pictures, 2009.

Film.11. Coutta, Ramsey. Storm Surger: A Novel of Hurrican Katrina. Xulon Press, 2006.

12. Crutcher, Michael E. Tremé, Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighbourhood. Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, 2010. Print.

13. Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time Image. London, New York: Continuum, 1989. Print.

14. Eggers, Dave. Zeitoun. London : Penguin Books, 2009. Print.

15. Feuer, Jane. “Genre Study and Television”. Channels of Discourse, Reassembled: Television and Contemporary Criticism. 1987. Ed. Robert C. Allen. London: Routledge, 1992. Print.

16. Fiske, John. Understanding Popular Culture. 1989. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

17. Harris, Scott Jordan. “Hollywood South”. World Film Locations: New Orleans. Ed. Scott Jordan Harris. Bristol & Chicago: Intellect Books, 2012. Print.

18. Kates, R. W., C. E. Colten, S. Laska, and S. P. Leatherman. “Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A Research Perspective”. PNAS 103.40, 14657, 3 Oct. 2006. <http://www.pnas.org/content/103/40/14653.full.pdf+html> Web. 16 July 2013.

19. Lee, Spike, dir. If God is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise. HBO, 40 Acres and a Mule, 2010. DVD.

20. ---, dir. When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. HBO, 40 Acres and A Mule, 2006. DVD.

21. Jameson, Kelly. What Remained of Katrina: A Novel of New Orleans. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012. Print.

22. Lipkin, Steven N. Docudrama Performs the Past. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011. Print.

23. Mizelle, Richard Jr. “Second-lining the Jazz City: Jazz Funerals, Katrina, and the Reemergence of New Orleans”, Wailoo, O’Neill, Dowd and Anglin 69–77. Print.

24. Morse, Reilly. “Environmental Justice Through the Eye of Hurricane Katrina”. Washington DC, Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, Inc., 2008. <http://www.jointcenter.org/hpi/sites/all/files/EnvironmentalJustice.pdf>. Web. 2 Feb. 2012.

25. Piazza, Tom. City of Refuge. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009. Print.

26. Polan, Dana. “HBO, The Sopranos, and Discourse of Distinction”. Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting. Eds. Sarah Banet-Weiser, Cynthia Cris, Anthony Freitas. New York: New York UP, 2007. Print.

27. Pollard, D.T. Rooftop Diva: A Novel of Triumph after Katrina. Bloomington : iUniverse, 2006. Print.

28. Shockley, Evie. “The Haunted Houses of New Orleans: Gothic Homelessness and African American Experience”, Wailoo, O’Neill, Dowd and Anglin 95–114. Print.

29. Stanonis, Anthony J. Creating the Big Easy: New Orleans and the Emergence of Modern Tourism, 1918–1945. Athens, Georgia: U of Georgia P, 2006. Print.

30. Tavernier, Bertrand, dir. In the Electric Mist. Ithaca Pictures, Little Bear, TF1 International, 2009. Film.

31. Treme. Season One. By David Simon and Eric Overmyer, 2010. HBO Home Video, 2011. DVD.

32. Treme. Season Two. By David Simon and Eric Overmyer. 2011. HBO Home Video, 2012. DVD.

33. Wailoo, Keith, Kareen M. O’ Neil, Jeffrey Dowd and Roland Anglin, eds. Katrina’s Imprint: Race and Vulnerability in New Orleans. New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 2010. Print.

34. Ward, Jesmyn. Salvage the Bones. London: Bloomsbury, 2011. Print.

35. Williams, Linda. Playing the Race Card, Melodramas of Black and White From Uncle Tom to O. J. Simpson. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2002. Print.

36. Wyler, William, dir. Jezebel. Warner Bros, 1938. Film.

37. Zimmerman, Patricia Rodden. States of Emergency, Documentaries, Wars, Democracies. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 2000. Print.

Suggested Citation

Letort, D. (2013) 'The tales of New Orleans after Katrina: the interstices of fact and fiction in Treme', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 5, pp. 101–115. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.5.07.

Delphine Letort is Senior Lecturer in the English Department at the University of Le Mans (France) where she teaches American civilisation and film studies. Her research explores the relationship between history, memory, and film in American fiction and nonfiction cinema—including war documentaries and African American films. She studies the ideological construction of stereotypes in relation to the politics of representation developed in Hollywood productions. Her latest articles focus on the notion of engagement on the part of committed filmmakers who use films to write counterhistory, shedding light on issues of race, class and gender in American society.