The Work of an Invisible Body: The Contribution of Foley Artists to On-Screen Effort

Lucy Fife Donaldson

On-screen bodies are central to our engagement with film; the ways they are framed and captured by the camera guides our attention to character and action, while their physical qualities invite a range of engagement from admiration, appreciation and desire to awe, fear and repugnance. The materiality of this embodied dynamic is often brought to the fore when we witness physical exertion, such as that presented in action movies or musicals, which invites increased kinetic and sensual alignment. We see a body jump, run, dance or crash and in response we tense, twitch, tap or flinch. The visual impact of on-screen labour is supported and enhanced by the sound a body makes when it moves: increases in the depth and rapidity of breathing communicate escalations in effort, a body straining to move faster; changes to the weight and rhythm of footfall indicate changes in the pace and force of the body moving. In short, sound plays a vital role in our perception of what film bodies are doing and experiencing.

Approaching ideas of effort and response draws attention to the ontological duality of performance, to the fact that our reactions are made in relation to the activity of a character and that of the actor. Considering character and performer in this way addresses a possible clash between rhetorical (filmed) body and actual body, yet this is not an ontological split between behaviour and thought/intention, but rather a material or sensorial doubling. Reflecting on the impact of sound, the role it plays in proprioceptively engaging our own kinaesthetic awareness in the physical experience of the on-screen body’s activity, raises further questions about whose effort are we responding to. The doubled relationship between on-screen bodies is further complicated if we consider that there is another body embedded in the filmmaking process: the body we hear. Through detailed analysis of moments from Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972) and Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988), this article explores the contribution of a body that is invisible in the finished film yet shapes our responsiveness to on-screen effort—that of the foley artist.

Effort and Performance

Consideration of “effort” in film addresses technical and aesthetic aspects of screen performance: the lengths to which a performer has gone to inhabit a role; visible technical skill; the physical exertions of a performer as a character. Attending to effort in the critical analysis of performance provides an opportunity to focus on physicality and the kinetic appeal of movement on-screen, the work of the body and the significance of this to our engagement with film. Clearly effort connects to a range of potential meanings, not all of which involve physicalised labour, but in attempting to unpick the affective contribution of foley work, I will focus on the detail of expressive qualities of energy used in movement. [1]

As sensory film theory seeks to remind us, the experience of watching films is embodied and experientially complex, even creating an impact on our watching bodies by generating physiological responses, like goose bumps. Scholars such as Vivian Sobchack, Jennifer M. Barker and Laura U. Marks highlight the processes of active reciprocation between bodies on-screen and that of the viewer. As they note, such sensuous engagement is constructed through the combination of our lived experiences and the work of our bodies. That is, our perception of film is informed and guided by the full complexity of our sensory experiences, “fleshed out” by our “lived bodies” (Sobchack, Carnal Thoughts 60), and “grasped … by the complex perception of the body as a whole” (Marks 145). Such approaches are significant in their recognition not only of the impact of film on the watching body, but also in the extent to which our engagement is shaped in reference to our own physical experiences. While Deleuzian ideas concerning attitude, posture and force explored through his conceptualisation of the movement-image and writing on the “cinema of the body” in Cinema 2: The Time-Image (182–215) provide a potentially useful approach, this article addresses effort and affect from a different perspective. Examining the expressive role played by the body on-screen requires attention to both its physical rhetoric and the material texture of film, that is anything that might qualify our responsiveness, including rhythm, proximity and quality of movement, force or effort.

Sensory Sound

Writing on sound often underlines the extent to which it is a material phenomenon. [2] Sobchack’s statement “I hear with my whole body” (“When the Ear Dreams” 10) conjures hearing as a tactile experience, while Rick Altman’s writing understands the processes of making and hearing sound as entailing molecular interaction with surrounding environments and surfaces (17–23). Such perspectives present the material qualities of sound as dissolving boundaries between exterior and interior, as sound penetrates to be felt within and through the body. Sound carries highly sensory qualities, its impact registered proprioceptively, or even interoceptively: “Sound can affect our body temperature, blood circulation, pulse rate, breathing, and sweating” (Sonnenschein 71).

The importance of the sensory contribution of sound has been long argued for by Michel Chion, who stresses that the spectacle of cinema is audiovisual, consisting of “sensations created by combinations of sound and images, greater than the sum of the parts” (“The Sensory Aspects” 235). A crucial element in Chion’s appreciation of the affect of film sound is to be found in his discussion of rendering, a concept which acknowledges that film sound is not necessarily concerned with the strict replication of reality, but rather the evocation of feeling and sensation in reference to real sound: it is “a sound that ‘translates’ not another sound but speed, or a force” (Film, A Sound Art 488). An example that Chion gives of rendering involves the contribution of sound to the body on-screen: “think of the sound effects that punctuate action scenes in many movies: the whirr and clank of swords and sabers in martial arts film translate agility; the sounds of punches in fight films translate the violence that the characters experience” (Film, A Sound Art 488). The kind of sound Chion is describing here is expressive, contributing to our sensuous engagement as it serves to “translate” character experience and the impression and quality of objects moving, the space they move in and their contact with other objects, bodies and surfaces.

Foley: Rendering a Performance

Foley artists recreate a range of sounds made by the body, including footsteps, breath, punches, falls and the sound clothing makes as actors move. Foley seeks to replicate how an action should sound, taking into account the feel of the object or surface with which the body on-screen is interacting: “A heavy cup in the film is a heavy cup on the Foley stage” (Ament 28). Their work also responds to how this interacting should sound in context, whatever the actor’s body is interacting with on set: “If Robin Hood bumps into a castle wall that happens to be made of plywood, the sound effect will have to be replaced … with the sound of the Foley artist’s bumping into the equivalent of thick stone” (Kawin 466). Rendering is at the heart of the process and depending on the film, foley can be made more or less realistic. Of course the question of aural fidelity is always a question of degree, but, as Chion observes, film sound is rarely retained in an original form even if it is recorded directly (Audio-Vision 95–6). What he terms the “illusion of unity” between the recording of diegetic sound and image relies on decisions made about what sounds to include and what to eliminate, as well as how to enrich or diminish them through postproduction (Audio-Vision 95). This may depend on the film’s genre, as noted by Sonnenschein: “The style of the film (especially comedy or terror) may allow exaggeration of the foley sounds” (41). What is included and excluded, what is enhanced and what is minimised, can be tied directly to expectations of the body and the kinds of affective relationship invited to it. In both a slapstick comedy and an action film, the particular sounds of the body falling or being hit are imperative for generating the kinds of responses associated with each genre (laughter on the one hand and perhaps exhilaration or apprehension on the other). The aural nature of the impact needs to be rendered appropriately to support the desired affect in reference to generic expectation.

In one sense, foley is about supplying the details of noises that we expect to be there from the action on-screen: footsteps when people walk, the rustle of fabric when a character looks through a cloth bag, the click of the safety catch when a gun is armed. Foley therefore involves producing a range of subtle sounds, and is probably the layer of the soundtrack that announces itself the least (though its prominence will be further determined by the kind of generic expectation mentioned above). As noted by scholars writing on film sound, the development of technology, in production, postproduction and exhibition, has allowed further opportunities for bringing increasingly intricate detail to the soundtrack. In his exploration of the aural counterpart to what David Bordwell has termed the “intensified continuity” of contemporary cinema (16–20), Jeff Smith identifies the “hyperdetail” of contemporary foley work, the kind of sounds created contributing to both diegetic realism and expressive force (343–5). For Smith, foley is one of a group of sound processes that “work in tandem with the visual strategies outlined previously, insofar as they function similarly to heighten the affective, sensory, and phenomenological dimensions of contemporary film style” (335). Contemporary foley artists themselves consider their work crucial to providing expressivity beyond realism, as exemplified by Dave Stone’s conception of his working process contributing a fullness or richness: “Foley adds character, personality and texture to cut sound effects that can be lifeless without it” (qtd. in Ament 32).

A crucial dynamic of this potential of foley to add life is in the interpretive role performed by the foley artist. Foley artists often have a background in performance, rather than sound work, at least partly due to the physical requirements of the profession; as Diane Greaves points out, “because you have to have good timing, a lot of the people who work as Foley artists … are dancers or have had drama school training where they have learnt to dance” (205). Having a person follow the actions of the actors, rather than using library or cut sound effects, embeds a physical presence into the process and creates opportunities for a nuanced approach to recording sound. Accordingly, foley artists view their work as expressive rather than simply functional: Kitty Malone sees the process as one that involves interpretation and embodiment (“You try to become that character” (63)), while Vanessa Theme Ament is even more direct in her statement that “Foley is a performance” (50). Understanding the embodied and expressive nature of foley is not intended to diminish the work of other sound personnel whose creative labour is also invisible and effortful, albeit in different ways. Nonetheless, the physicalised nature of foley and the bodily exertion and energy that goes into creating sounds that match bodies and their interaction with surfaces on-screen has perhaps a more pronounced relationship to considerations of physical affect than other areas of sound design.

In order to further explore the corporeality of foley work, I will use two examples to illustrate certain key features of the process: Track Stars: The Unseen Heroes of Movie Sound (Terry Burke, 1979), a documentary short consisting of an action sequence shown alongside two foley artists performing accompanying sound via split screen, and Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, 2012), a fiction film which centres on the production of the soundtrack (including mixing, recording—both ambient sound and voice, foley and editing). In different ways, both offer dynamic illustrations of what foley involves and the creativity involved in rendering sound.

A fundamental element of foley work is choosing the right combination of surface and movement in order to render sound as the most appropriate match for on-screen action. This may involve replicating components of performance and mise en scène exactly, however, it is more likely that other alternatives will be sought. This is chiefly for reasons of practicality, which Walter Murch explains as relating to convenience, necessity and morality (for example, “the sound of a watermelon being crushed instead of a human head” (xix)). As the film being made in Berberian Sound Studio is a horror film, nearly all the foley performed on-screen is a rendering of violence done to the body, with stand-in surfaces/objects chosen not just for the moral reasoning indicated by Murch, but also, and more significantly, for the intensity of their visceral qualities. The sound of flesh being sliced and tortured offscreen in the film-within-a-film is replicated by the handling of fruit and vegetables by the protagonist, Gilderoy (Toby Young), and resident foley artists Massimo (Pál Tóth) and Massimo (Jozef Cseres) on-screen, who chop, stab and rip watermelons and radishes, manipulate cabbages in water to simulate a drowning body, and so on. The substitution of such surfaces for flesh reveals the widely varying scale of correspondence between visual action and sound, and, moreover, that the foley process is specifically shaped to achieve the most directly felt aural texture.Practicalities of foley work contribute to further mismatches between sound and image in relation to the performing body. As a brief moment in Berberian Sound Studio establishes, when the sound of footsteps (“the stealthy Signora Collatina”) cuts to a close-up of Massimo’s feet in high heels, there is quite a large potential gap between the physical make-up (including gender) of on-screen and offscreen performers. Such corporeal mismatching illustrates that for the foley artist their body is another tool and surface at their disposal. Furthermore, in order to render sound that registers the appropriate amount of weight and impact at the right time, the body and its actions are deployed with a great degree of control. The foley artists of Track Stars can be seen expending energy throwing punches, falling over and into objects to recreate the contact and falls of the actors. Not only must they move with precision to create impacts that bring the appropriate degree of force to the sound of someone falling or being hit, but they also need to be quick to recover in order to move on to the next sound.

Distinctions between the on-screen and offscreen body further indicate that the quality of energy expended by actor and foley artist is the result of a continuous tension between control and force. As both examples confirm, foley is typically done in a restricted space, so foley artists are required to perform movement on the spot. The split-screen action of Track Stars reveals further the distinctions between the nature or quality of movement of actor and foley artist, demonstrating how very different kinds of bodily propulsion, from very light tiptoeing to forceful running, is achieved through scrupulous control of gait and weight placed on the foot. To recreate fast running, for example, the foley artist exaggeratedly increases the height of his knees as he runs in order to maximise the weight in the full contact between the sole of his foot and the floor.

Track Stars enables scrutiny of foley artists concurrent with the action they are matching, while Berberian Sound Studio presents the work of sound design almost entirely separate from its matching image. Both reveal something that is kept hidden from our usual experience of film, and in doing so dramatise the affective contribution of sound. Berberian Sound Studio further indicates how sound alone can conjure the qualities of bodily movement and affect. Apart from a brief glimpse late in the film, the action to which the sound is being matched remains offscreen and while certain visual and aural clues inform us of what is happening (Gilderoy’s repulsed reactions, scene descriptions given by the sound man in the booth, close-ups of soundtrack notes), the sound alone evokes clearly the action and visceral horror of traumatised flesh.

Invisibility/Inaudibility

The invisibility/inaudibility of foley clearly creates difficulties in writing about it. Foley is purposely not called attention to, as it is typically a background sound on the soundtrack (though its emphasis may also vary according to genre), and for this reason it can be tricky to identify separately from other sound effects, or single out from its place within the sound mix. One strategy to assist identification, which I have adopted in this article, is to listen for foley that filmmakers (principally foley artists themselves) have identified and discussed. For the purposes of analysis, especially in terms of considering the achievement of foley as a performance, its invisibility creates further difficulties. As Track Stars makes clear, foley performances are full of expressive gestures, movement and energy—all the elements that are generally analysed in an actor’s performance—yet this physical achievement and its kinetic detail can only be inferred. The contribution of sound to film acting is often limited to analysis of voice, though as Pamela Wojcik argues, the disruption of coherence between the body on-screen and recorded sound is a tremendous additional challenge to considering the relationship between the production of sound and acting (73–80). [3] As well as feeding into larger debates about authenticity embedded in the filmmaking processes and its “illusion of unity”, valuing foley performance inevitably raises questions about the hierarchies of attention to filmmaking personnel in film criticism, and the separation between scholarship attentive to expressive achievement and to technological processes.

The act of making foley visible/audible contributes to understanding filmmaking as a fragmented and layered process—something that mainstream cinema often seeks to efface, its various audiovisual strategies seeking to smooth over any breaks or gaps. Foley thus enhances what Mary Ann Doane has termed “the material heterogeneity of the ‘body’ of the film” (172); it is one component of the many layers recorded separately and brought together in the final product. As with the performance of the actor, which “occurs in multiple time segments—multiple and repeated moments of actors’ performances in production, postproduction, and exhibition” (Wojcik 78), foley consists of various performances (or “passes”), multiple efforts that are woven into a coherent whole. [4]

Footsteps: Fleshing Out Movement

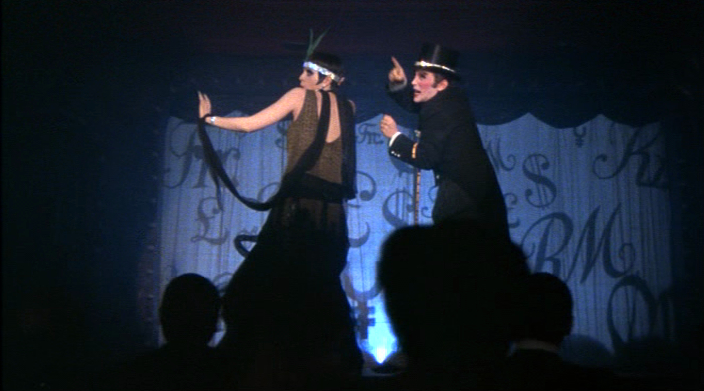

The two examples I will explore in detail focus primarily on the sound of feet, in films chosen both for their emphasis on physical effort and bodily movement—a musical and action film respectively. The first is Cabaret, a film on which director/choreographer Fosse and foley artist Kitty Malone performed foley for the dance sequences. In her interview with Vincent LoBrutto, Malone recounts her experience of working on the film, and makes reference to the number I will discuss: “Money, Money”, a duet performed by Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli) and the Master of Ceremonies (Joel Grey) at the Kit Kat Klub. Adapted from a stage musical, Cabaret is a backstage or show musical, with all of the musical numbers (except one) taking place onstage in the club. “Money, Money” occurs immediately after Sally meets Maximilian (Helmut Griem), a wealthy bachelor with whom she and her lover Brian Roberts (Michael York) become involved. While the number can be understood as straightforwardly connecting to the narrative and character—the meeting leads the impoverished Sally to excitement at the prospect of “divine decadence” enjoyed courtesy of a generous patron—the performance space of the club is characterised by parody and even grotesquerie, [5] modes of performance and stylisation which more precisely position the number as a piece of commentary placed to inflect our potential enjoyment of its spectacle and to qualify understanding of the characters’ actions. This parodic mode is communicated through camera movement and mise en scène, and furthermore through relationships between movement and sound built into the performance: between verses the characters throw coins at one another and shimmy and thrust provocatively to the accompaniment of musical cues of honks and rattles provided by the club’s orchestra. This sequence offers opportunity to consider how the sound of footsteps contributes to awareness of physical movement and its qualities, and more particularly how this frames the sense of bodily movement and space when it occurs offscreen.

Figure 1: An instance of the stylised and restrained posing in a long shot set-up of “Money, Money”. Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972). Warner Home Video, 1988. Screenshot.

The dancing that takes place during “Money, Money” is not pronouncedly effortful; rather it offers stylised formations of bodies, and tensions between restrained posing and kinetic energy—physical qualities that are characteristic of Fosse’s choreography more broadly, and, as noted by Kelly Kessler, can be understood in terms of its cynical and transgressive qualities (Figure 1). The bodies of Minnelli and Grey shift between stiffened postures and bursts of fluidity through isolated sections of the body (from the waist, knees or hands), while the sound of their feet are consistently clipped and crisp, the only modulation being in weight and density: from lighter toe sounds to heavier contact made with the whole body through the heel. Seeing dance on-screen relies emphatically on the matching of sound and image, and it is important that not only are these elements in sync, but also that they match in terms of weight (as implied by amplitude, pitch and resonance) and rhythm. This is straightforward enough, yet footsteps are often missing from dance sequences even when feet are visible, either covered by the dominance of music or merely absent (the exception being tap sequences, where the sound is a fundamental element of the dance). Thus, the decision to make their feet audible here, even though the number does not feature tap, demonstrates an interest in what this kind of sound contributes to the number as a whole (as a layer of sound additional to music/voice) and a recognition of its value in communicating detail of movement. While Fosse’s choreography might belie effort in its stylisation and restraint, the level of physical control is clear. Kessler identifies this as a central aspect of Fosse’s work, which “became iconic and recognizable for its … crisp, in-depth manipulation of the body through dance, slow movement, and meticulous attention to detail” (120). The inclusion of clear, crisp footsteps in the sequence draws out this attention to detail, and the meticulousness of physical movement.

Figures 2 and 3: The heads of the audience in the Kit Kat Klub obscure views of Minnelli and Grey’s feet; in another long-shot set-up, the heads also obscure a view of their feet, while the framing of the performers increases the distance from detail of the body. Cabaret. Warner Home Video, 1988. Screenshots.

Another crucial effect of including the sound of feet is that even when the dancing bodies are obscured, an understanding of the manner and range of movement is conveyed. The visual treatment of this number is fragmented—another characteristic trait of Fosse’s approach—shifting between a variety of set-ups, only five of which feature the full bodies of Minnelli and Grey. Furthermore, in the most prolonged long-shot set-up, which is used twice, the camera is placed within the club’s audience, so that silhouettes of heads obscure a full view of the performers’ feet (Figures 2 and 3). Due to these decisions about framing, foley works to affectively “flesh out” the quality of movement for significant periods of the characters’ dancing. When, about halfway through the number, Minnelli and Grey come together from opposite ends of the stage, pacing rhythmically while shimmying their torsos as they sing, their voices become louder, and rather than being drowned out by the increased vocal volume, their footsteps become louder in correspondence. This higher amplitude creates a sense of force, both in terms of their bodily impact on the stage, disclosing the emphatic nature of their movements, and in rendering the idea of a crescendo of activity before they meet. Sherril Dodds identifies differences between live and screen dance as channelled through the restrictions of editing and space (30–5), and though these are framed as both negative (screened dance is flatter and distanced) and positive (it can be enlivened through detail and temporal distortion), foley can be understood to significantly contribute to the three-dimensionality of dance (and other kinds of movement) on-screen through its expansion of corporeal impact even when the body is not visible.

Figure 4: The close framing and stillness of Minnelli and Grey’s heads as they move, makes it difficult to discern movement. Cabaret. Warner Home Video, 1988. Screenshot.

José Gil writes of the dancing body creating space through movement, transforming a scene (specifically a performance space) by investing it with “affects and new forces” where “although invisible, the space, the air, acquires a diversity of textures” (85). The quality of the footsteps in this scene conveys the detail of an emphatically controlled physical movement that we cannot see. Furthermore, the stillness of Minnelli and Grey’s heads in these shots and moments later—when they dance upstage together in close proximity while maintaining a focused gaze on one another, their faces turned and lips puckered as though to kiss—makes it difficult to discern any range of movement in their bodies (Figure 4). Instead, it is the sound of their feet that communicates the detail of action. The small moment of separateness and then proximity is embodied further by the aural shift from a dynamic of force (the strong momentum forwards as a crescendo) to lightness as they dance alongside one another. Here foley, integrated into the louder sounds of music and voice, dramatises the kinetic dynamics of offscreen activity, communicating the corporeal play between elasticity and stiffness in its shifts between harder/sharper and softer/lighter textures. The degree of force and rhythm adopted by the foley artist(s) anchors our experience of dance that is not consistently visible, filling in precise dynamics of energy and control that contribute to the inference of shifting physicalities. This may also inflect response to the film’s detached and parodic characterisation, and thereby the particular quality of affective forces created through the space of the body.

Footsteps: Vulnerability and Resistance

The second example I will explore is Die Hard, the narrative of which concerns the successful struggle of an off-duty police officer, John McClane (Bruce Willis), to thwart the highly organised heist of a large corporation in Los Angeles. As we might expect from an action movie, decisions concerning visual style and performance foreground the physical effort of its central character. Over the course of the film, McClane’s appearance becomes increasingly dishevelled, sweaty and bloodied as a result of falling down stairs, travelling on top of an elevator, climbing through air ventilation shafts, being shot at, punched and so on. As Lisa Purse notes, there is a tension between physical mastery and the loss of control informing the “fantasies of empowerment” that shape experiences of the action body. Action films, she argues, “allow us to ‘feel’ this mastery for ourselves through our sensorial connection with the body of the hero” (45).

Figure 5: McClane (Bruce Willis) works his toes into the carpet. Figures 6–10: Close-up of McClane’s feet as he talks to Hans Gruber/Bill Clay;walks on glass; drags himself into the bathroom; pulls glass out of his feet; stands on his bleeding and bandaged feet. Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988). Twentieth Century Fox, 2000. Screenshots.

During Die Hard, the limits on the possibilities of McClane’s physical mastery are underscored by prominent visual references to his bare feet (he has taken off his shoes after a long flight), as he attempts to prevent the attack on Nakatomi Plaza. This pattern of attention to his feet is first introduced as he works his toes into the carpet shortly after his arrival at the office block (Figure 5). It is then developed through several key moments during the heist: during his exchange with the leader of the criminal gang, Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) who is pretending to be American in order to trap McClane (Figure 6); when Gruber orders his followers to shoot out all the glass in an office, leaving McClane surrounded by broken shards that he must cross to escape (Figure 7); while dragging himself into a bathroom, his lacerated feet leaving a bloodied trail behind him (Figure 8); when, having removed the glass, he stands tentatively on his bleeding and bandaged feet (Figures 9 and 10). These moments offer localised opportunities for us to engage with McClane as a physical presence, to be involved with his body and the specific impacts the action has on it, in a way that addresses what Purse terms the “real-world borderline between the physically possible and impossible” established by shifts between sensorial recognition and fantasy in the effort of the action body and its affect (46). McClane’s feet present an example of “sensorial recognition”, as they are as unprotected and soft as ours might be, and therefore his activity, though extreme, maps with our own basic experiences of walking barefoot and its inherent risks. However, these shots become increasingly significant as a mark of his “pronounced physical resilience and unusual amount of luck” (Purse 46), going beyond what most of us would be able to endure.

To this point the discussion of McClane’s feet has been limited to their significance to narrative and character through moments of visual prominence. Ostensibly, the contribution of their sound might be regarded as less prominent, as footsteps in the film are typically one of several layers of sound, including music, dialogue and other sound effects. However, in keeping with the action genre’s concern with engaging the viewers’ immersion in spectacles of bodily risk, the foley track ensures that the feet affectively contribute to our sensorial engagement with McClane, with even more consistency than the visual image. With modulations in acoustics, volume and pitch, the foley here communicates information about the spaces McClane occupies and his movement through them: his footsteps are soft, almost inaudible, as he treads cautiously on carpet; they create a fleshier slap as he darts across harder floors. Ament mentions her work on Die Hard as an example of the challenge of performing foley, specifically in terms of a controlled degree of force in order to render the footsteps as audibly bare and appropriately prominent: “I had to walk barefooted, but with more weight and emphasis than if I had a shoe on” (78). McClane’s footsteps differ from all the other characters, clarifying his energy and impact in comparison to his adversaries. Foley creates a particularly sharp contrast between McClane and Gruber, whose footsteps are characterised by a hard, clipped sound. Ament describes the process of auditioning shoes, observing that Robin Harlan, her partner on the film who “walked” Alan Rickman’s character, “selected a gorgeous-sounding pair of shoes that had a rich and authoritarian sound. [Gruber] was the boss of the whole operation, and he needed to sound ‘in charge’” (78).

In this respect, footsteps shape the general qualities of characters’ personality, narrative position and differences (in this instance, hero versus villain). Their aural qualities also provide information about environment (whether it is hard, soft, large, small), and how the body moves through it (walking, running). More specifically, aural qualities supplied by foley work attune us to the kind of effort being expended by a character, and the nature of their relationship to a space. Thus, the work of the foley artist shapes characterisation, and also the sensory qualities of a character’s experience, and provides further understanding of the body in space/the space of the body. A key example of this is the moment when McClane works his toes through the carpet: his action is accompanied by a soft brushing sound, louder in a close-up of his feet and quieter as the camera moves up to focus on Willis’s face. The sound of the friction between foot and carpet is soft and steady: he is trying to relax and his feet are smooth and fleshy, qualities that inform our own possible ease at this stage. In contrast, when Gruber, posing as “Bill Clay”, looks at McClane’s blackened bare feet and McClane flexes his toes, the accompanying foley features a small slapping sound in reference to the hard floor. This “slap” constructs the feet as vulnerable—the clash of flesh and polished stone—and perhaps as harder than previously, the tension in his gesture conveyed through the shorter, flatter sound, and likewise alerts our own apprehension. The culmination of the contribution of foley to communicating McClane’s experiences occurs when he stands on his injured feet. Here the foley track underlines his physical hesitancy caused by pain in a series of light rustling impacts, the primary source of noise being the foot’s contact with newspaper covering the floor, rather than pressure on the floor itself. Even when his feet are out of sight, the soundtrack continues to reference them, alluding to the pain he is experiencing as he shifts his weight from one foot to the other, never placing his full weight on either. The achievement of foley in Die Hard goes beyond a process of filling in the kinetic and material qualities of physical movement and the body’s spatial trajectories. It works to describe the sensory experience of characters—efforts and achievement of mastery and empowerment—and, more specifically, McClane’s struggles to overcome his physical limits.

Conclusion

While foley offers the possibility of a qualification to the ontological status of film acting, adding another body to the layers of a performance’s achievement, my analysis does not seek to diminish what the body on-screen does, or its affect. Rather, it draws attention to the collaborative nature of filmmaking and recognises the density of film’s audiovisual design. A further area of consideration, relevant to expanding the corporeal dynamics at work in the compression of on-/offscreen performance, would be the gender transferences involved between actor and foley artist.

The moments I have examined foreground the range of possible affects contributed by these details, including mapping the qualities of offscreen action, creating distinctions between characters and space, and describing the sensory experiences of characters. By considering the energy, rhythm, weight and force of movement conveyed by the sound of footsteps in two very different films, this article invites further reflection on the contribution of foley to the affective qualities of on-screen bodies. Although it is typically intended that foley remain in the background, its subtle contributions develop an array of detail concerning the body’s movements. Ament’s declaration that “Foley should be ‘sensed and not heard’” speaks to the importance of its proprioceptive impact (xv). However, rather than a dissolution between interior/exterior, film body/our body as is so often proposed by sensory film theory, I argue that this sensing is significant to mapping bodily effort and describing physical experience, attuning but not overlapping with our own. By registering impact and movement, the space of the body created through foley is transformative, forceful but also separate, the precise delineations it affords the body’s textures a result of its emphatically controlled rendering.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Lisa Purse, Douglas Pye, Faye Woods and the anonymous readers for their invaluable comments on the article, and to Ian Murphy and Gwenda Young for their vital editorial guidance.

Notes

[1] In this respect, use of “effort” can be connected to Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), an observational framework developed by choreographer Rudolf Laban for the qualitative and quantitative study of human movement. Elsewhere, I have considered in more detail how LMA can contribute to analysis of film performance seeking to underline kinaesthetic empathy conjured by on-screen effort (Donaldson 2011: 158–74).

[2] In my book Texture in Film I discuss the contribution of sound to the materiality of film in more detail, and how its various affective qualities—from the concrete perceptions of sound referred to by Altman and Sobchack here, to the capacity for sound effects and music to fill space and shape atmosphere—have been addressed by a range of writers (Donaldson 2014: 114–15).

[3] Wojcik notes that Sergi’s writing on sound technology acknowledges the contribution of sound designers to film performance, but keeps the two distinct (75).

[4] There are of course a multitude of other invisible bodies contributing to the affect of the on-screen body, within the sound department and elsewhere in a production/postproduction team (for example, the costume designer who dresses the body and therefore makes decisions about the materiality of the body’s surfaces and how an actor moves through a space, and the editor who shapes the rhythmic qualities of movement and so on). For the purpose of this article, I am singling out one element in a complex flow of labour, and by focusing on the role of “effort” in physical affect, I am necessarily privileging labour as a physical process, which, of course, it is not exclusively

[5] Linda Mizejewski addresses the film’s grotesquery in reference to its treatment of female sexuality, and how this works to trouble the position of the film viewer (5–17).

References

1. Altman, Rick. “The Material Heterogeneity of Recorded Sound”. Sound Theory, Sound Practice. Ed. Rick Altman. New York/London: Routledge, 1992. 15–31. Print.

2. Ament, Vanessa Theme. The Foley Grail: The Art of Performing Sound for Film, Games and Animation. Boston: Focal Press, 2009. Print.

3. Barker, Jennifer M. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: U. of California P., 2009. Print.

4. Bordwell, David. “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary Hollywood Film”. Film Quarterly 55.3 (2002): 16–28. Print.

5. Burke, Terry, dir. Track Stars: The Unseen Heroes of Film Sound. Movement Films/Film Arts, 1979. Film.

6. Cabaret. Dir. Bob Fosse. 1972. Warner Home Video, 1988. DVD.

7. Chion, Michel. “The Sensory Aspects of Contemporary Cinema”. The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics. Eds. John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis. Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2013. 325–30. Print.

8. ---. Film, A Sound Art. 2003. Trans. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia U.P., 2009. Print.

9. ---. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. 1990. Trans. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia U.P., 1994. Print.

10. Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. 1986. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Roberta Galeta. London: Continuum, 2009. Print.

11. Die Hard. Dir. John McTiernan. 1988. Twentieth Century Fox, 2000. DVD.

12. Doane, Mary Ann. “The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space”. Film Sound: Theory and Practice. 1980. Eds. Elizabeth Weis and John Belton. New York: Columbia U.P., 1985. 162–76. Print.

13. Dodds, Sherril. Dance on Screen: Genres and Media from Hollywood to Experimental Art. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001. Print.

14. Donaldson, Lucy Fife. “Effort and Empathy: Engaging with Film Performance”. Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural Practices. Eds. Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason. Bristol: Intellect Books, 2011. 158–74. Print.

15. ---. Texture in Film. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Print.

16. Gil, José. “Paradoxical Body”. Planes of Composition: Dance, Theory and the Global. Eds. André Lepecki and Jenn Joy. London/New York/Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2009. 85–106. Print.

17. Greaves, Diane. “Diane Greaves (Foley Artist)”. Let the Credits Roll: Interviews with Film Crew. By Barbara Baker. Jefferson: McFarland, 2003. 203–8. Print.

18. Kawin, Bruce. How Movies Work. Berkeley: U. of California P., 1992. Print.

19. Kessler, Kelly. Destabilizing the Hollywood Musical: Music, Masculinity and Mayhem. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Print.

20. Malone, Kitty. “Ross Taylor and Kitty Malone”. Sound-On-Film: Interviews with Creators of Film Sound. By Vincent LoBrutto. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1994. 61–68. Print.

21. Marks, Laura U. The Skin of the Film. Durham: Duke U.P., 2000. Print.

22. Mizejewski, Lisa. “Women, Monsters, and the Masochistic Aesthetic in Bob Fosse’s Cabaret”. Journal of Film and Video 39 (1987): 5–17. Print.

23. “Money, Money”. Cabaret: Original Soundtrack Recording. John Kander, Ralph Burns and Fred Ebb (comp.). Hip-O Records, 1996. CD.

24. Murch, Walter. “Foreword.” Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. 1990. By Michel Chion. Trans. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia U.P., 1994. vii–xxvii. Print.

25. Purse, Lisa. Contemporary Action Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh U.P., 2011. Print.

26. Sergi, Gianluca. The Dolby Era: Film Sound in Contemporary Hollywood. Manchester: Manchester U.P., 2004. Print.

27. Smith, Jeff. “The Sound of Intensified Continuity”. The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics. Eds. John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman and Carol Vernallis. Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2013. 331–56. Print.

28. Sobchack, Vivian. Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: U. of California P., 2004. Print.

29. ---. “When the Ear Dreams: Dolby Digital and the Imagination of Sound”. Film Quarterly 58.4 (2005): 2–15. Print.

30. Sonnenschein, David. Sound Design: The Expressive Power of Music, Voice, and Sound Effects in Cinema. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2001. Print.

31. Strickland, Peter, dir. Berberian Sound Studio. Warp X/Illuminations Films, 2012. Film.

32. Wojcik, Pamela. “The Sound of Film Acting”. Screen Performance. Spec. Issue of Journal of Film and Video 58.1/2 (2006): 71–83. Print.

Suggested Citation

Donaldson, L. F. (2014) 'The work of an invisible body: the contribution of foley artists to on-screen effort', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 7, pp. 79–93. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.7.05.

Lucy Fife Donaldson has taught Film at the universities of Reading, St. Andrews and Bristol, and is currently a postdoctoral researcher on the AHRC-funded project “Spaces of Television: Production, Site and Style” at the University of Reading. Her research focuses on the materiality of film style and the body in popular film and television and she is a member of the Editorial Board of Movie: A Journal of Film Criticism. Her book Texture in Film is due to be published by Palgrave Macmillan in June 2014.