Art as a Guaranty of Sanity: The Skin I Live In

Tarja Laine

The title of Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In (La piel que habito, 2011) clearly communicates what the film is all about: the body as a prison with the skin as a barrier. This is already evident in the opening shots of the film, in which the image of the locked gate of El Cigarral, an isolated Toledo villa, dissolves into the image of a barred window. Behind this window a woman in a nude-coloured bodysuit is practicing yoga. This woman is Vera (Elena Anaya), a mysterious patient of Robert Ledgar (Antonio Banderas), a brilliant plastic surgeon haunted by past tragedies. Later we will discover that Vera used to be a man by the name of Vicente (a character played by Jan Cornet), who was abducted by Robert after his involvement in a fateful event at a wedding party that triggered his daughter Norma’s (Blanca Súarez) final mental breakdown and her subsequent suicide. After a period of imprisonment in a filthy cellar, Vicente is forced to undergo a sex change operation and he resurrects in the form of Robert’s deceased wife Gal. In many respects The Skin I Live In is best understood as a psychological thriller, in which Robert becomes a kind of modern-day Doctor Frankenstein, but whereas Frankenstein aimed at gaining insight into the creation of life and eventually did give life to his own creature, Robert’s goal is to manipulate life by means of transgenic mutation and plastic surgery. He is driven by a pathological obsession arising from his grief at the loss of loved ones, which develops into extreme revenge.

Themes of desire, obsession and revenge are recurrent in Almodóvar’s oeuvre. His films have often been defined as melodramas originating from unresolved grief for “lost homosexual attachments” and especially the loss of the mother (Williams, “Melancholy Melodrama” 283; Bersani and Dutoit 117). Almodóvar’s melodramas can be described as examples of what Linda Williams has termed “body genre”, since they often stage the “spectacle of a body caught in the grip of intense sensation or emotion” (“Film Bodies” 4). In previous scholarship, the body in Almodóvar’s cinema has been studied from the perspective of (trans)gender and (homo)sexual identity politics (e.g. Smith; Maddison; Pérez), as a bodily/national metaphor (Acevedo-Muñoz; Kinder), and as a vehicle of performance (Albilla; Guse). This article also examines Almodóvar’s discourse of the body, but from a different perspective. It considers how the body in The Skin I Live In is incorporated in artistic creation and vice versa. Drawing upon Paul Crowther’s notion of an internal relation between the artist’s experience and the work of art, it argues that the film communicates a vision of embodied artistic practice as a redemptive strategy used to resolve trauma resulting from the traditional body/soul dualism. A film that outlines how artistic creation can both express fractured inner reality and purge it from negative affect, The Skin I Live In demonstrates how the artist can overcome trauma, reinvent the sense of self, and reclaim personal agency.

This process of expressing and purging negative affect is founded in the intensity with which the film both confirms and reverses the logic that, as John Berger has argued, has put women in the role of object to be viewed in art (45). The mise en scène of The Skin I Live In is dominated by copies of various works of art, most notably Venus of Urbino (1538) and Venus and Music (1547) both by Titian, as well as Dionisios encuentra a Ariadna en Naxos (2008) by Guillermo Pérez Villalta (which is typically considered a homage to Titian with its comparable theme and image composition). Both the film and the works of art featured in it explore the myth of the artist and artistic creation, and Vera herself can be seen as an artwork created by Robert. Even her first name Vera, which means “the true one”, is given to her by Robert, but towards the end of the film she chooses her own surname Cruz (crucifix, a symbol for suffering) as an important agential gesture. [1] Vera is frequently seen on the huge screen in Robert’s bedroom in a frontal pose that resembles Venus in a Titian painting or in a posterior pose that references another Venus painting not seen in the film: Diego Velásquez’s The Rokeby Venus (1647–1651). In one scene Robert lies down in front of the screen, diagonally opposite to Vera, the artist as male subject admiring his creation, the female object (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Artist admiring his work of art. The Skin I Live In (La piel que habito, Pedro Almodóvar, 2011). Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

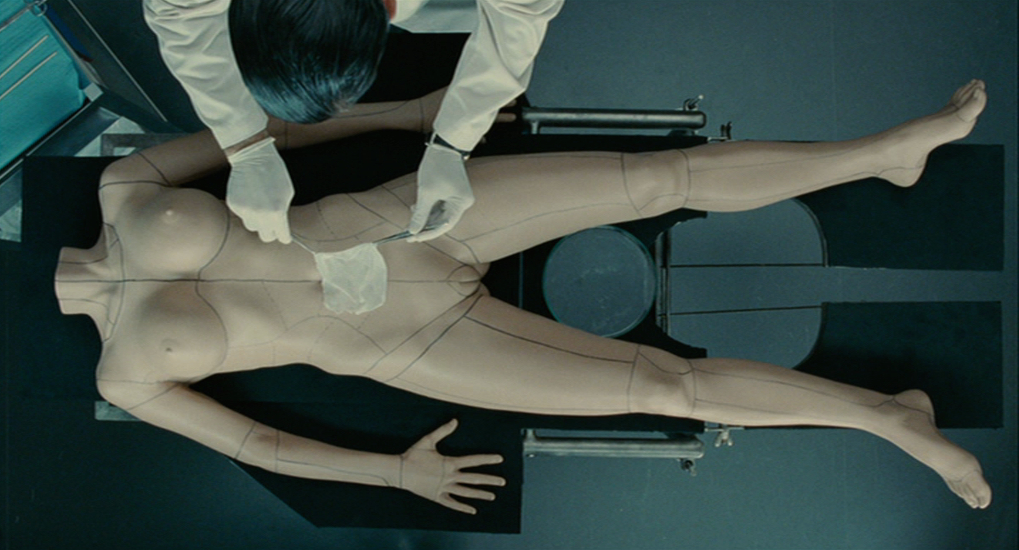

This dualistic representation of male as subject and female as object of (artistic) creation is central to the first part of the film. We often witness Robert cultivating his invention of artificial skin, which he has created by combining the genetic material of a pig with that of a human being. [2] In The Skin I Live In, the manufacturing of skin is a form of art, and plastic surgery is equivalent to artistic expression. After creating a new patch of skin, Robert is seen from a bird’s-eye perspective, while tightly fitting a piece of skin on a mannequin moulded to look exactly like his deceased wife; immediately afterwards he uses the same piece to form a new layer of skin on Vera’s neck (Figure 2). At this point the film deliberately offers no narrative backstory for the events on screen and we are led to believe that Vera is a creature Robert has fabricated from scratch, a living work of art or a transgenic masterpiece. The film’s meticulous attention to the scientific details of the skin-manufacturing process also reinforces this false belief: as Vera murmurs to Robert in one early scene: “I’m yours… I’m made to measure for you.”

Figure 2: Modelling skin. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

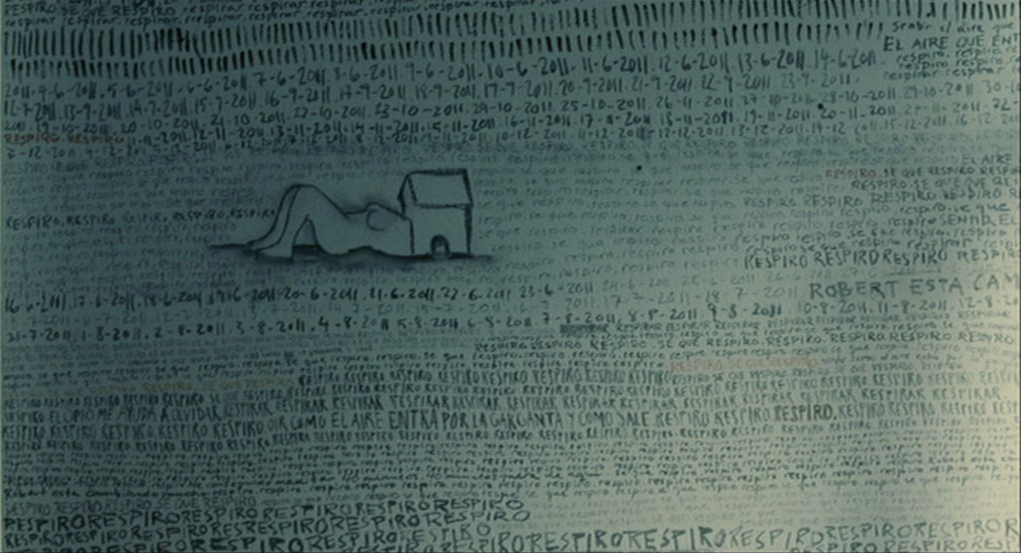

In the second half of the film, however, such dualistic images of artistic expression, with the male as subject and the female as object, disappear once Vera discovers her own creative potential. The artistic process involves an internal relation between the gender transformation and the resulting works of art, which enables Vera to respond to her trauma and mitigate its effects. This is signalled soon after her transformation is complete when Robert sends her makeup products, which she refuses to accept, apart from lipstick and an eye pencil. In some feminist discourse, makeup is considered an enforced adorning regime for the female body, used to reflect prevailing ideals of femininity. [3] Instead of using these products to augment her sexual desirability, however, Vera employs them in her wall writings. First, she draws tally marks to count the days of her solitary confinement. As soon as she learns from housekeeper Marilia (Marisa Paredes) what the current day and year is, she starts writing down the actual dates, starting from the day that Vicente was abducted by Robert. During the course of her imprisonment she not only fills the wall with date marks, but also with sentences such as “El opio me ayuda a olvidar. Respiro. Respiro. Respiro. Sé que respiro” (“Opium helps me to forget. I breathe. I breathe. I breathe. I know how to breathe”). In addition, she executes drawings of yoga poses, and surrealist drawings that depict female bodies and torsos, standing or lying down with their heads entrapped in small houses. [4] These self-conscious references to Louise Bourgeois’s work, most notably her sculpture Femme Maison (1994), invoke the traditional, Platonic metaphor of body as a prison-house, a hollow, evil, vessel-like space that encloses the soul. [5] This metaphor is especially apt, if we consider Vera’s experience of skin as something alien, an impermeable boundary between the self and the world—a skin to “live in”.

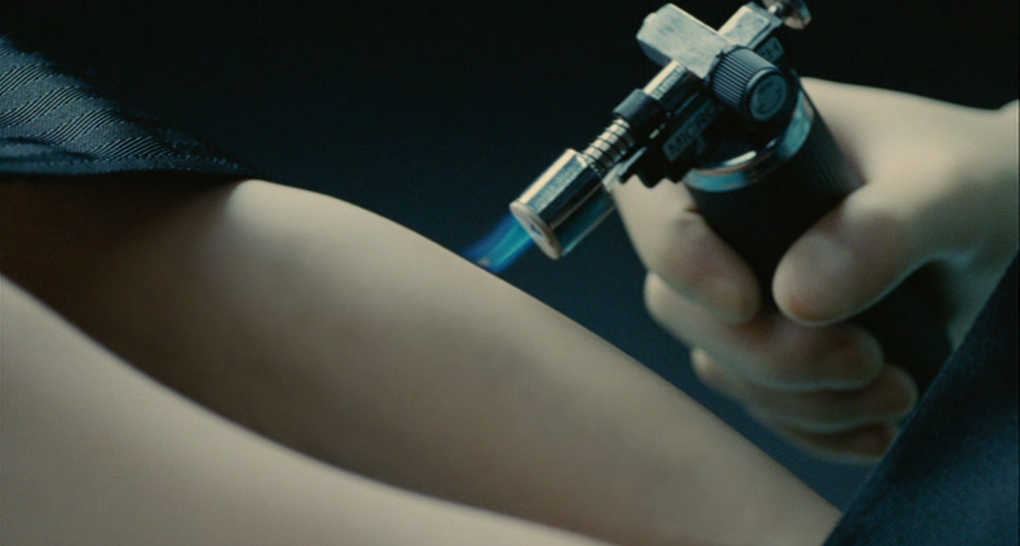

In Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Julia Kristeva stresses the importance of skin and the role of the mother in establishing a boundary of self to an infant through constant caressing and touching. Through tactile contact, it is the mother who presents a skin to the child. In The Skin I Live In Vera’s skin does not “belong” to herself but to Robert, and it imprisons her inside her own body. Extraordinarily strong, the artificial skin Robert has created is resistant to extreme heat and insect bites, but lacks sensitivity to tactile contact and sensory perception. At first, Vera does not even seem to feel the heat of the flame that Robert uses to “caress” her skin (Figure 3), leading Rob White and Paul Julian Smith to conclude that this is a film all about desensitisation, disaffection and a deficit of feeling, one that is ultimately as “surgically chilly” as its protagonist, Robert (White and Smith). Certainly, it is disaffection that compels Vera to mutilate herself, using the sharp edges of the dust jackets of the Cormac McCarthy books (The Orchard Keeper and Blood Meridian) that lie scattered, blood-stained, all around her room. Her lack of skin sensation means that she experiences being the object she has become—Robert’s creation—and her self-mutilating can be seen as her attempt to get under the artificial skin, to feel something. Vera’s nude-coloured bodysuit, which functions as a “second skin”, imprisons her further inside her own body and closes her off from tactile contact with the world.

Figure 3: Impenetrable skin. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

Clothing is often understood as our second skin, defining our gendered identity. As Kaja Silverman argues: “Dress is one of the most important cultural implements for articulating and territorializing human corporeality—for mapping its erotogenic zones and for affixing a sexual identity” (146). After her sex change operation, Robert provides Vera with a number of feminine dresses precisely for this purpose, but she destroys the dresses, aggressively protesting her enforced sexual identity. Later she uses the dresses as material for her artwork, and it is at this point in the film that a different conception of clothing as a second skin starts to emerge. In this respect it is significant that in her previous life Vera/Vicente used to be a tailor: this knowledge enhances our understanding of how the film finally aims at dissolving the existing dualism between her as a creation and Robert as a creator. As Marilia (Robert’s biological mother) observes, Robert tailors women, moulding them into his ideal of a perfect woman and into the image of his deceased wife Gal, but Vera tailors herself using her artwork in an attempt to rid herself of the membranous identity fashioned for her by Robert. As Paul Julian Smith, in his discussion with Rob White points out, this “therapeutic suture” is simultaneously an act of deconstruction and reconstruction of identity (White and Smith).

As noted, The Skin I Live In frequently invokes art history references to help delineate its themes, and there is an interesting parallel here between Vera’s artwork and that of the Italian artist Alba D’Urbano, for whom skin is a primary concern. In her 1994 work Hautnah (“skintight”) she traced the form of her body digitally, and then rendered it into a dress-pattern, which she tailored into a suit that could potentially be worn by others (and which, incidentally, strongly resembles the actual body suit worn by Vera in Almodovár’s film). For D’Urbano the skin becomes “a site of convergence between inner consciousness and outer reality … the imaginary activity of abandoning one’s own skin or putting on somebody else’s” (Wegenstein 31). [6] The imaginary activity of abandoning one’s skin is of primary importance in Vera’s artwork. In one scene it is significant that she first puts on a shredded dress before proceeding to use a nail file to rip it further. Her tearing of the dress while she is wearing it might be seen as an act of metaphorical self-mutilation. Almodóvar gives us a close-up of her hands as they cut the fabric, which, with its nude tones, is exactly the same colour as the second skin bodysuit she is wearing, thus evoking the sensation that she is cutting her own skin (Figure 4). Importantly, this self-mutilation functions as a source of creativity and not as a (futile) attempt to restore a sense of self. By shedding her second skin in the form of ripped dresses, Vera finds a way to abandon the outer reality forced upon her, and to give expression to her traumatic inner reality.

Figure 4: Self-mutilation as a source of creativity. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

These themes are reflected in her other artwork. Interestingly, one of Vera’s sculptures portrays a head that is covered in bandages, such as would be applied after serious head injury, while another clearly resembles the agonised figure in Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893); both evoke pain and (inner) suffering, externalised by the symbolic shedding of skin (Figure 5). This shedding of skin could therefore be considered cathartic, purging the negative affect residing under her skin. According to Silvan Tomkins, affect resides in the skin, being mediated by specific sensory receptors all over the body. The skin does not merely express affect “closed off” inside but instead, “leads rather than follows” the affective movement of which it is an extension: “The skin is not simply an ‘expression’ of internal dynamics, nor is it limited in its motivational properties to the affect system. [Affects] all compel and persuade powerfully via stimulation of skin receptors, with or without benefit of further imagery or cognition” (42). In contrast to this idea of affect residing in the skin, the flawless and extremely strong artificial skin that Robert invents and brand-names Gal seems designed to confine affect inside Vera’s body. Nevertheless, in a procedure similar to Robert’s coating artificial skin on her body, Vera is able to shred her symbolic dress-skin, fitting pieces of it on her plasticine sculptures. By this act of defiance she is able to externalise the agony residing under her skin, purging her traumatic inner reality from negative affect.

Figure 5: Vera’s agony externalised in sculptures. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

Vera’s psychic conflict originates from a crisis of identity in the aftermath of her forced sex change operation. Her psychic trauma and the horror of sensory unresponsiveness that is the result of the artificial skin are mirrored in the case of Gal, the ghost from Robert’s past. Thus, even though the death of his daughter was the trigger that impelled Robert to perform transgender surgery on Vicente, the person he inadvertently resurrects is not Norma but Gal. Many years before, Gal ran away with Robert’s half-brother Zeca (Robert Álamo), but when their car crashed and burst into flames, she was left for dead and badly burnt, her skin virtually non-existent. [7] Her epidermal sensations profoundly reduced, she is condemned to a deathly existence, unable to move, to remember, or to communicate verbally, wrapped tightly in bandages, entirely dependent on her husband. For Gal, the loss of skin is essentially a loss of agency, and her failure to recognise herself in her own reflection generates an identity crisis so severe that she is driven to suicide. In Lacanian thinking, it is famously the mirror that creates a sense of ego for an infant, though this is simultaneously a misrecognition, the ego always being a mediated image that is already alienated from the self. In Gal’s case, her whole self becomes unrecognisable, her internal self-image forever unmatchable with its mirror image—a situation she finds unbearable.

As noted, there is a congruity between Gal’s fate and Vicente/Vera’s physical situation in The Skin I Live In. There is a telling scene in which Vicente stands in front of the mirror after his vaginoplasty. In the first shot he is shown standing on a chair in order to see his genitalia in a small round mirror. We then see the mirror in medium shot, showing a reflection of Vicente’s torso, but with his head “cut off” by its edges (Figure 6). Finally, we get a medium close-up of Vicente’s face. The montage effect used here suggests that Vicente’s mirror image and his self-image are permanently alienated and, like Gal before her suicide, this lack of recognition of self triggers a crisis of identity. Later in the film Vera will restore a sense of self when she glimpses an image of herself as Vicente, in a blurry photograph in a newspaper left behind on a table by Robert’s colleague. First she stares at the photo intensely, then bends down to kiss it, and finally she caresses it with her fingertips. Thus it is touch, rather than vision, that restores her sense of self, and this moment of tactile perception is connected to the creative possibility of touch by which Vera produces her sculptures. Female creativity, then, is used to facilitate a restoration of male identity, and it also leads up to Vera’s ultimate act of agency: her killing of Robert and Marilia. The final line in the film is: “I’m Vicente”, after which the image slowly fades to black. With this conjunction of sound and image, Almodóvar indicates the disparity between the presentation of a female body and the reiteration of Vicente’s core identity.

Figure 6: Identity crisis reflected in the mirror. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

In ending the film in this way, Almodóvar indicates that even though Vicente and Vera are actually the same person, there is a crucial difference between the person Vicente and who he appears to be as the persona Vera. For spectators it is very difficult to see the two as one character, even after we have learned about Vicente/Vera’s past. This may be partly due to the fact that the central mystery (that Vera is Vicente) takes a long time to unfold. This only occurs at the 43-minute mark when the narration shifts from present to past, to the events that took place six years before. The flashback is realised as a double dream sequence. Opening with a shot of Robert and Vera sleeping in the same bed, the camera descends vertically from directly above Robert, and then dissolves to a close-up of the bell of a saxophone, playing Sidney Bechet’s “Petite Fleur” at what emerges as the fateful wedding party. The sequence ends abruptly with Robert waking up from his nightmare in the present. The camera then moves to a close-up of Vera’s face, with the right side illuminated and the left side in shadow, leaving us with the suggestion that her self is divided into a past and a present identity. This dissolves into a shot of Vicente busy in the vintage store he runs with his mother, after which past events start to unfold from his perspective. The sequence ends with a shot that is best described as a superimposed split screen, in which Vera in the present is shown on the left of the frame while Vicente, in the past, faces her on the right side. This image conveys the impression that Vicente and Vera are one and the same person, and references one of Vera’s own drawings that depicts a head with two profiles facing in opposite directions, divided in the middle by a female figure. Evoking the head of Janus, the Roman god of transitions, in this drawing one face is looking into the past (Vicente) and another into the future (Vera) and thus it communicates Vera’s identity crisis.

(Re)invention of the Self

In his book Art and Embodiment: From Aesthetics to Self-Consciousness, Paul Crowther argues that the essence of art is the conservation and expression of embodied human experience. In The Skin I Live In the monotonous nature of Vera’s living conditions is expressed in the recurring images, words, and sentences that she scribbles on the wall, which make the psychological effect of her solitary confinement tangible for the spectator. The uniformity of her daily routine is analogous to the regularity of her breathing, and it is as if she consciously needs to remind herself to breathe (“sé que respiro”). After she has been released by Robert, Vera enters her room and stops to observe the scribbled wall (Figure 7), positioning herself in front of one sentence that stands out from all the other sentences because of its size. It proclaims “El arte es garantía de salud” (“Art is a guaranty of sanity”), a motto that encapsulates the philosophy of the film. Art is a guaranty of sanity insofar as it becomes an outward projection of negative affect, enabling the enactment and working through of traumatic experience (Bennett 67). Vera’s wall art is executed out of the need to document experience and self-exploration, which is a fundamental factor in the artistic motivation of many female artists, including Louise Bourgeois, whose art, as previously noted, is prominently featured in The Skin I Live In.

Figure 7: Vera’s scribbled wall. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

Indeed Bourgeois uses the sentence “Art is a guaranty of sanity” in one of her most famous installations, Precious Liquids (1992), in which the visitor is invited to enter a wooden chamber that contains bottles filled with bodily “precious liquids” (blood, milk, sperm, and tears). Bourgeois is an artist in whose work metamorphosis and personal memory as a source for creativity stand out as fundamental themes. She has executed a great number of works using fragments of the body, including genitals, in a way that produces gender fluidity rather than fixity. For instance, while her sculpture Fillette (1968) seemingly represents a penis, it might also be seen to represent a stylised female torso, as the title (“little girl”) indicates. Bourgeois has also created a series of works featuring her own apparel, including lingerie and cocktail dresses mounted on hangers made of old beef bones (Untitled, 1996). In her analysis of Untitled (1996) Griselda Pollock argues that this artwork signifies both the externalisation of the artist’s body and the display of clothing to render a “masquerade of identity” (96). According to her, Untitled (1996) embodies a chasm between identity as experienced in the past and the present identity, when the physically transformed exterior confronts the subject with an “alien independence of the body” (96).

Bourgeois’s fabric sculptures—also made from the artist’s undergarments— such as Rejection (2001), Seven in Bed (2001) and Untitled (2001), become the most important source of inspiration for Vera’s artwork in The Skin I Live In. Vera’s works of art, made from her clothing, share significant parallels with Bourgeois’s fabric sculptures and express both her experience of living in an “alien skin” and the gender identity that she is “dressed in”. Almodóvar makes clear the convergence between Vera’s work and Bourgeois’s in a sequence in which Vera watches snippets from the documentary Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine (Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach, 2008). This documentary displays Bourgeois’s sculptures, which seem to embrace each other, in detail. The camera lingers especially on the unique seams of these sculptures, which are visually associated with Vera’s own seams/scars (Figure 8). Like Bourgeois’s sculptures, Vera’s skin looks as though it has been assembled from pieces of fabric, her body a patchwork in which different sections are simultaneously united and divided by scars. Patchwork is also the method by which Vera finishes off her plasticine sculptures. In the opening sequence we see her cutting through thin, skin-coloured fabric by means of a nail file, which causes a pronounced shredding sound. As already argued, the fabric symbolises Vera’s own skin, her self. Thus in The Skin I Live In, skin can be read in two ways: as a barrier (as expressed by Vera’s artificial skin and her bodysuit) and as a symbol for a powerful sense of self (embodied in the skin-like fabric of her artwork). Indeed, skin as an effective symbol for the self is evident from idioms such as “to save one’s skin”, “to get under one’s skin” or “to jump out of one’s skin”, expressions that Claudia Benthien argues demonstrate its relation to subjectivity: “Here the essence [of self] does not lie beneath the skin, hidden inside. Rather, it is the skin itself, which stands metonymically for the whole human being” (18).

Figure 8: Skin as patchwork. The Skin I Live In. Pathé, 2011. Screenshot.

By using symbolic skin as material for her artwork, Vera is able to externalise her inner suffering, which correlates with the concept of art as a guaranty of sanity, and to reclaim her agency. And for Crowther this is precisely the function of art. He argues that the artistic process involves a “symbolically significant sensuous manifold”, an inherent relation between the artist’s existence and the resulting work of art (4). This relationship is borne out of our fundamental need for recognition from outside ourselves: acts of “self-externalisation”, such as producing works of art, help one “to ascribe experiences to oneself” (Crowther 150), a process, which for a trauma victim, is blocked. Art significantly satisfies the need of an individual “to be at home with himself or herself” (Crowther 7) insofar as it embodies the ontologically reciprocal relations between the subject and the world: “The artwork … reflects our mode of embodied inherence in the world, and by clarifying this inherence it brings about a harmony between the subject and object of experience” (Crowther 7). In The Skin I Live In, Vera’s embodied experience involves her being torn apart and then stitched back together. Her works of art bear physical witness to her carnal familiarity with feeling like a “ragdoll”, as she is sewn up by Robert from pieces of artificial skin. While Robert exercises power over her by resculpting her muscles and remoulding her body parts, Vera is able to empower herself, at least to some extent, by reproducing the plastic surgery process in her plasticine art. If artistic creativity is understood as constructing something that expresses certain aspects of the artist’s lived experience, then creativity and agency must necessarily be overlapping notions. By depicting Vera explicitly reconstructing her existential pain in her ragdoll art, The Skin I Live In offers a vision of creativity as an embodied, agential practice with redemptive potentiality.

As Vera watches Cajori and Wallach’s documentary on Bourgeois’s art, one piece astonishes her. Untitled (2001) represents a figure with an ambiguous gender identity that, when viewed from different angles, appears to be either a lying, corpulent female torso with legs spread apart, revealing an opening as if giving birth, or else a huge penis. Similarly, Vera’s sculptures are either androgynous, with deep holes instead of eyes, or feminine and masculine at the same time: one object seems to represent the upper part of a female figure with breasts, a long neck and an oblong head, but its form might equally be seen to resemble a phallus. In Seven in Bed Bourgeois represents a child’s imagination of the Freudian primal scene that is based on her own traumatic family history. Assembled from pieces of knitted pink fabric and consisting of seven bodies (some of them Janus-faced) entangled in an orgiastic embrace in bed, the artwork is at once erotically charged and disturbing, ever maintaining a sense of distance between the spectator and the trauma embodied in it. It is this piece that clearly inspires Vera to construct a bust of a three-headed figure—in which two heads passionately kiss—an artwork that may be considered a symbolic reference to the traumatic triangular relationship between Robert, Vera and Vicente (Figure 5). The kiss itself anticipates a gesture at the end of the film, when Vera kisses her own image as Vicente and, in doing so, rescues herself from the traumatic identity fastened onto her by her creator.

According to Crowther, in creating an artwork artists engage with their own embodied experience of a creative idea, which is an internal process grounded in the medium, i.e. paint, clay, stone, etc. In acts of artistic creation, handling the medium anchors the artist’s inherent involvement with the creative idea, informed by past experiences. This is why artwork is an embodiment of human experience, and the actual, physical work that remains is

discontinuous with the artist’s actual bodily states, and yet … preserves both his or her style of experiencing the subject or idea, and implicitly, all the experience which informed the creation of the work. It is experience become concrete, and intersubjectively accessible. It is a microcosm of the artist’s own being. (Crowther 46)

In The Skin I Live In, Vera’s artwork both embodies and expresses her trauma, while performing the healing function of the creative process. In general, to be a person is to ascribe experiences to oneself, but in trauma this process is blocked. Referring to the work of Pierre Janet, Jill Bennett explains that experiences are normally processed through cognitive schemata that enable them to be identified, interpreted, and given a narrative and/or semantic meaning. Traumatic experiences, however, resist such processing, while the victims yearn to find some meaning in the trauma (Bennett 23). Since trauma remains stored in somatic memory as imagery, creating art can provide a means to overcome it. According to Valerie Appleton, artistic creation engages the trauma victim in sensory, affective, and cognitive novelty, rather than traumatic repetition. Therefore it can lead to a sense of catharsis. She writes that the artistic process “has the effect of bringing into manageable form those otherwise overwhelming experiences” and through the creation of art “mastery is achieved when conflict is re-experienced, resolved, and integrated” (9). For Pollock, because trauma lacks intelligibility and meaning, a memory of the event that triggered it has to be created:

The art work’s otherness … its function simultaneously as laboured and thus externalized projection of some inner compulsion of the subject who produces it … These recalcitrant materials … coming into art necessitates the very invention of forms, materials, texts, sites, in which the traumatic offence … could become memory, could find some manageable relief. Being now a memory, however, these materials are no less painful; they have become simply less unmastered and predetermined. (90)

In Almodóvar’s film Vera’s art is a successful attempt to resolve the trauma of her altered physical appearance and distorted social identity, her struggle with the chasm between how Vera looks and who Vicente is. Her figurines represent symbols of the self, expressing the struggles of her identity crisis and her emergence out of the chaos of her traumatic experience. Vera frequently revisits the original event of forced transgender operation, and it seems no coincidence that plasticine is her favourite choice of material, as the word’s meaning is associated with plastic surgery. As such it cements Vera, a creation of art, to Robert’s own artistic creation. The closing credits of the film run on top of a black screen showing a rotating double helix made of chains, which continually changes colour as the direction of its rotation slows down, speeds up, stretches and shrinks. This double helix expresses the defining sensibility and inner dynamics of the film, providing us with insight into the complex relations between the work of art and the identity of its creator. The final image, then, is an apt metaphor for a film that conveys an entangled understanding of the artist and the work of art, presented to the spectators in a form that truly “gets under their skin”.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Charles France, Ian Murphy, Gwenda Young and the two anonymous reviewers of the early draft of this article.

Notes

[1] Caron Harrang argues that Vicente’s own name, which is derived from vincere and means “he who is to conquer”, is also symbolically significant, as it functions as a signpost for his “journey on the path toward psychic liberation” (1306). The name Vera Cruz is one of the many intertextual cinematic references in the film. It refers to Robert Aldrich’s 1954 western with Gary Cooper and Burt Lancaster. Another obvious filmic reference is Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (Les Yeux sans visage, 1960), in which an eminent Paris surgeon kidnaps young women and removes their faces, attempting to graft them onto his daughter, who has been disfigured in a car crash.

[2] At the same time, the numerous close-ups of cell culture dishes and of various stages of differential centrifugation, combined with close-ups of living wasp and beetle colonies, have a repugnant effect as they suggest even more complex transgenic practices than between two species only.

[3] See for instance Andrea Dworkin’s Women Hating: “In our culture not one part of a woman’s body is left untouched, unaltered … From head to toe, every feature of a woman’s face, every section of her body, is subject to modification” (113–4).

[4] Throughout the film Vera is shown practicing challenging yoga poses, always in elegantly composed images. It is evident that yoga serves the same purpose as her artwork, enabling her to find a confirmation for her sense of self.

[5] The film calls a great deal of attention to Bourgeois’s work, not only in its inclusion of clips from the documentary Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine (2008) but also in shots that show Vera reading a book on her art. The viewer is left in no doubt that both Almodóvar and Vera are inspired by her work.

[6] Xavier Aldana Reyes draws a similar comparison between Vera and French artist Orlan, who uses plastic surgery in order to expose Western beauty myths and to show how skin can function as a garment to dress up as a female subject. However, for Vera this process of “becoming-woman” is destined to be an impossibility (826).

[7] Zeca’s character also wears a bodysuit, but whereas Vera’s bodysuit functions to conceal her true identity, Zeca’s tiger suit actually reveals it. It is a carnival suit, and Zeca himself is an excellent personification of the Bakhtinian grotesque body: dominated by corporeal, primal needs such as eating, drinking and sex, and apparently void of any moral considerations about his actions.

References

1. Acevedo-Muñoz, Ernesto. “The Body and Spain: Pedro Almodóvar’s All About My Mother”. Quarterly Review of Film and Video 1 (2003): 25–38. Print.

2. Albilla, Julián Daniel Gutiérrez. “Body, Silence and Movement: Pina Bausch’s Café Müller in Almodóvar’s Hable con ella”. Studies in Hispanic Cinemas 1 (2005): 47–58. Print.

3. Aldrich, Robert, dir. Vera Cruz. United Artists, 1954. Film.

4. Almodóvar, Pedro, dir. The Skin I Live In [La piel que habito]. Pathé, 2011. DVD.

5. Appleton, Valerie. “Avenues of Hope: Art Therapy and the Resolution of Trauma”. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 1 (2001): 6–13. Print.

6. Bechet, Sidney. “Petite Fleur”. 1952. Sound recording.

7. Bennett, Jill. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford: U. of Stanford P., 2005. Print.

8. Benthien, Claudia. Skin: On the Cultural Border Between Self and the World. Trans. Thomas Dunlap. New York: Columbia U.P., 2002. Print.

9. Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 1972. Print.

10. Bersani, Leo and Ulysse Dutoit. Forms of Being: Cinema, Aesthetics, Subjectivity. London: British Film Institute, 2004. Print.

11. Bourgeois, Louise. Femme Maison. 1994. White marble. Cheim & Read Gallery, New York. Sculpture.

12. ---. Fillette. 1968. Latex over plaster. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Sculpture.

13. ---. Precious Liquids. 1992. Cedar, iron, water, glass, alabaster, fabric, embroidered cushions, clothing. Musée National d’Art Moderne. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Installation.

14. ---. Rejection. 2001. Fabric, steel and lead, aluminium and glass. Cheim & Read Gallery, New York. Sculpture.

15. ---. Seven in Bed. 2001. Fabric, stainless steel, glass and wood. Cheim & Read Gallery, New York. Sculpture.

16. ---. Untitled. 1996. Cloth, bone, rubber and steel. Cheim & Read Gallery, New York. Sculpture.

17. ---. Untitled. 2001. Fabric and steel. Cheim & Read Gallery, New York. Sculpture.

18. Cajori, Marion, and Amei Wallach, dir. Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine. Zeitgeist Films, 2008. Film.

19. Crowther, Paul. Art and Embodiment: From Aesthetics to Self-Consciousness. Oxford: U. of Oxford P., 1993. Print.

20. D’Urbano, Alba. Hautnah. 1995. Fabric. Sindelfingen Gallery, Stuttgart. Installation.

21. Dworkin, Andrea. Women Hating. New York: Dutton, 1974. Print.

22. Franju, Georges, dir. Eyes Without a Face [Les Yeux sans visage]. Lux Film, 1960. Film.

23. Guse, Anette. “Talk to Her! Look at her! Pina Bausch in Pedro Almodóvar's Hable con ella”. Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies 4 (2007): 420–40. Print.

24. Harrang, Caron. “Psychic Skin and Narcissistic Rage: Reflections on Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In”. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 93 (2012): 1301–8. Print.

25. Kinder, Marsha. “Reinventing the Motherland: Almodóvar’s Brain-Dead Trilogy.” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 3 (2004): 245–60. Print.

26. Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Trans. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia U.P., 1982. Print.

27. Lacan, Jacques. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience”. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977. 1–7. Print.

28. Maddison, Stephen. “All About Women: Pedro Almodóvar and the Heterosexual Dynamic”. Textual Practice 2 (2000): 265–84. Print.

29. McCarthy, Cormac. The Orchard Keeper. New York: Random House, 1965. Print.

30. ---. Blood Meridian. New York: Random House, 1985. Print.

31. Munch, Edvard. The Scream. Oil, tempera and pastel on canvas. 1893. National Gallery, Oslo. Painting.

32. Pérez, Jorge. “The Queer Children of Almodóvar: La mala educación and the Re-sexualization of Biopolitical Bodies”. Studies in Hispanic Cinemas 2 (2012): 145–57. Print.

33. Pérez Villalta, Guillermo. Dionisios encuentra a Ariadna en Naxos. 2008. Oil on canvas. Painting.

34. Pollock, Griselda. “Old Bones and Cocktail Dresses: Louise Bourgeois and the Question of Age”. Oxford Art Journal 2 (1999): 73–100. Print.

35. Reyes, Xavier Aldana. “Skin Deep? Surgical Horror and the Impossibility of Becoming Woman in Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In”. Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 7 (2013): 819–34. Print.

36. Silverman, Kaja. “Fragments for a Fashionable Discourse”. Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture. Ed. Tania Modleski. Bloomington: U. of Indiana P., 1986: 139–52. Print.

37. Smith, Paul Julian. Desire Unlimited: The Cinema of Pedro Almodóvar. London: Verso, 1994. Print.

38. Titian. Venus and Music. 1546. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Painting.

39. ---. Venus of Urbino. 1538. Oil on canvas. Uffizi, Florence. Painting.

40. Tomkins, Silvan S. Exploring Affect: The Selected Writings of Silvan S. Tomkins. Ed. E. Virginia Demos. Cambridge: U. of Cambridge P., 1995. Print.

41. Velàzquez, Diego. Rokeby Venus. 1647–1651. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London. Painting.

42. Wegenstein, Bernadette. “Body”. Critical Terms for Media Studies. Eds. W.J.T. Mitchell and Mark B.N. Hansen. Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 2010: 19–34. Print.

43. White, Bob and Paul Julian Smith. “Escape Artistry: The Skin I Live In”. Film Quarterly 10 (2011): 1–8. Web. 1 Apr. 2014. <http://www.filmquarterly.org/2011/10/escape-artistry-debating-the-skin-i-live-in/>.

44. Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess”. Film Quarterly 4 (1991): 2–13. Print.

45. ---. “Melancholy Melodrama: Almodóvarian Grief and Lost Homosexual Attachments”. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 3 (2004): 273–86. Print.

Suggested Citation

Laine, T. (2014) 'Art as a guaranty of sanity: The Skin I Live In', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 7, pp. 24–38. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.7.02.

Tarja Laine is Assistant Professor of Film Studies at the University of Amsterdam, and Adjunct Professor of Film Studies at the University of Turku, Finland. She is the author of Feeling Cinema: Emotional Dynamics in Film Studies (Bloomsbury, 2011) and Shame and Desire: Emotion, Intersubjectivity, Cinema (P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2007). Her book Bodies in Pain: Emotion and the Cinema of Darren Aronofsky is forthcoming from Berghahn Books in February 2015.