Corporeality and Embodiment in the Female Boxing Film

Katharina Lindner

“The [female] boxing movie is a mesmerising ballet of guts and gumption, a cinematic riff on the latest, most physical fusion of woman to warrior.” (Rich 16)

This article engages with the cinematic genre in which the body is perhaps most explicitly on display: the boxing film. Boxing performances have been an integral part of cinema since its very early incarnations and the long history of boxing in cinema highlights the ways in which a fascination with the human body in motion is intimately tied up with the medium’s historical evolvement (Auerbach; Streible). In Hard Core Linda Williams argues that cinema has incorporated bodies and bodily movements in specifically gendered ways since its inception, reinforcing associations of masculinity with an active, intentional physicality and of femininity with a self-conscious passivity (39–40). The boxing film, traditionally assumed to be about a male boxer, carries contradictory significance in this regard: the boxing body is certainly characterised by a powerful, assertive and intentional physicality. However, bodily injury and pain are an equally central aspect of the sport and the exposed male body on display, often in close proximity to other exposed male bodies, may also be inscribed with troublingly (homo)erotic possibilities (Oates; Cook; Wood). The genre is therefore considered to be a space in which the tensions around masculinity—specifically in relation to race and class—can be worked out (Baker; Woodward). Leger Grindon in particular has shown how this working out of masculinity in crisis is intimately tied up with the (visual, narrative, thematic) conventions of the genre itself (Knockout).

It is from within this critical frame that this article explores the unsettling implications of the recent proliferation of the female protagonist in the boxing film. Through an analysis of Million Dollar Baby (Clint Eastwood, 2004) and Die Boxerin (About a Girl,Catharina Deus, 2004), it provides insights into the incorporations of the female boxer in a range of cinematic contexts. Directed by legendary actor-director Clint Eastwood, [1] Million Dollar Baby features a number of well-known Hollywood stars (Eastwood himself, Morgan Freeman and Hilary Swank as the female boxer), and was the recipient of a variety of accolades, including Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress in Leading Role (Swank) and Best Actor in Supporting Role (Freeman). In contrast, Die Boxerin, a German film starring Katharina Wackernagel as a female boxer, marked the directorial debut of Catharina Deus, and had only limited theatrical release in Germany and elsewhere (it was screened at the London Gay & Lesbian Film Festival in 2006). [2]

Critical accounts of the female boxing film have begun to acknowledge its subversive potential, often by drawing on the conceptual possibilities provided by queer theory. For instance, discussions of Girlfight (Karyn Kusama, 2000)—arguably the film that triggered the recent influx of female protagonists into the genre—have been concerned with the transgressive implications of the heroine’s embodiment of masculinity (Caudwell; Fojas, Heywood and Dworkin; Lindner, “Fighting for Subjectivity”; Rich). Die Boxerin, on the other hand, has not received much critical attention, and while the significance of the female boxer in Million Dollar Baby has been explored (e.g., Boyle, Millington and Vertinski; Woodward), the film has been discussed primarily in the context of Eastwood’s recent directorial outputs and the male melodrama (e.g., Modleski; M. Williams; Sklar and Modleski). This article therefore provides an in-depth engagement with Die Boxerin and Million Dollar Baby in order to explore the ways in which the female boxer’s corporeality, variously and contradictorily, challenges gendered representational conventions. It builds on existing work by situating both films more specifically in the generic context of the boxing film, rather than the melodrama, the action genre or in comparison to “real-life” women’s boxing. [3] It moves beyond an account of the female boxing body’s symbolic significance (in terms of “how it looks”) and towards a consideration of the female boxer’s queer modes of embodiment. The phenomenological perspective employed here acknowledges the lived, sensory and affective experience of boxing and of what Sara Ahmed terms the “queer orientations” of the female boxer (70). The article also opens up possibilities to account for the embodied engagements facilitated by the female boxing film, and uses recent work on cinema and embodiment (e.g., Barker) to explore the boxing films’ corporeal and sensory regimes.

Boxing Women on Screen and Beyond

Joyce Carol Oates and Kath Woodward assert the continuing importance of boxing to the working out of tensions and contradictions around masculinity—both in terms of the embodied practice of boxing and in terms of spectatorship: “In no other sport is the connection between performer and observer so intimate, so frequently painful, so unresolved” (Oates 59). The boxing film plays an important role in this regard, through the creation and circulation of boxing myths and legends, and the psychic and fantasy investments thus made possible (Woodward 4–5), as well as through the potential reshaping of the “connection between performer and observer” explored by Oates. The entry of female athletes into the sport is therefore troubling: not only does the female boxer’s embodiment of masculinity undermine binary understandings of the gendered body; female boxing also unhinges the discursive, psychic and, I would argue, embodied investments in boxing masculinities that the sport has historically facilitated for its consumers (Woodward). In short, as Oates observes, “Boxing is for men and is about men, and is men” (172; emphasis in original). Oates’s assessment here, as Woodward notes, “is not only an empirical observation about the people who take part, but an expression of the powerfully gendered metaphors of the sport” and of its “draw” (3). Such an understanding highlights the unsettling implications of women’s attempts to enter the social, physical and generic spaces of boxing (brought into sharp focus with the opening up of the sport to female athletes in the 2012 Olympics) as well as of women’s embodiments of the boxer’s habitus (Hargreaves).

The relatively recent entry of the female protagonist into the boxing film genre gains significance within this critical frame. It is useful to note the parallels between the action genre and the boxing (and more generally sports film) genre, in terms of how female protagonists fundamentally undermine the (narrative, thematic, visual, spectatorial) conventions of historically male-centred genres that revolve around male bodily display (Lindner, “Bodies in Action”). Arguably, the gender transgressions within the sports/boxing film are particularly unnerving, due to the ways in which queer embodiments of gender are lived by female athletes/boxers outside of the representational realm of cinema. The recent emergence of the boxing heroine resonates profoundly with the larger sociocultural challenges to lived gender norms that are perhaps made most visible by real-life female athletes and their very corporeal embodiment of gender trouble (Butler, “Athletic Genders”).

Ahmed’s phenomenological account of queer embodiments and orientations is particularly useful in this regard. Ahmed emphasises the corporeal dimensions of queerness, linked, as they are, to our expressive and perceptive relations to the world. This enables a move beyond accounts of the symbolically transgressive significance of women’s boxing towards a consideration of the queer potentialities of the female boxer’s reshaping of conventionally straightforward bodily relations to time and space. The focus in Ahmed’s work is on “how bodies are gendered, sexualised and raced by how they extend into space”, and she offers “a model of how bodies become orientated by how they take up space and time” (5). She argues that normative embodiments of gender, sexuality and race tend not to be experienced as specifically orientated, since white, straight bodies are already aligned with the straightforward whiteness of phenomenal space: “When we are orientated, we might not even notice that we are orientated: we might not even think ‘to think’ about this point” (5). She suggests that it is only when bodies do not extend space comfortably—when the body does not “fit”—that we might experience the impressions left by the world and others as violent and painful: “When we experience disorientation, we might notice orientation as something we do not have” (5).

Boxing as a bodily activity provides a magnification of the reciprocal relations between, and mutual moulding of, bodies and spaces and the ways in which bodies are shaped by histories and habits. Boxing (training) is all about reshaping the body and embodying a powerful and violent yet disciplined orientation; it is about the repetition of bodily movements and gestures until they become “second nature”. In this sense, Ahmed’s argument recalls Judith Butler’s notion of performativity and adds a specifically corporeal dimension, countering frequent criticisms of queer theory as privileging surface over (physical, bodily, corporeal) depth. Inhabiting a boxing body tends to be equated with the embodiment of an, albeit antiquated and frequently (self-)destructive, masculine ideal. With its emphasis on the individual isolated in the ring, the body as the only available tool, boxing is the sport that most poignantly inscribes masculinity on the materiality of the male body. Boxing enables the embodiment of a particularly forceful and assertive, yet damaging, orientation towards the world, others and the self—an orientation that not only helps to keep gender binaries in place but also helps to keep hierarchies of masculinity, and relations of difference between men (in terms of race, class and sexuality), intact. Women’s embodiment of boxing masculinities therefore unhinges a whole range of symbolic, discursive and embodied structures and their performative reconstitution. [4]

Cinema provides particular “incarnations” of time and space—in the mobile human figure that occupies and organises the spaces of cinema (Auerbach 2) and in the cinematic movements and gestures that embody particular orientations towards the world (Barker 3). Arguably, cinema is also capable, then, of articulating those embodiments of time and space, those (dis)orientations and those phenomenological relations to the world that Ahmed defines as “twisted” or queer. [5] She argues that:

It is not just that bodies are moved by the orientations we have; rather, the orientations we have toward others shape the contours of space by affecting relations of proximity and distance between bodies … orientations involve different ways of registering the proximity of objects and others. Orientations shape not only how we inhabit space, but how we apprehend this world of shared inhabitance, as well as ‘who’ or ‘what’ we direct our energy and attention toward. (3)

Queer orientations disrupt the straightforward experience of normative phenomenal space by reshaping ways of extending space and the relations of proximity and distance that come with it, so that different objects and others come into view, are reachable, are within our horizon and leave impressions on us.

Embodied Encounters with the Female Boxer in Million Dollar Baby and Die Boxerin

Grindon’s discussion of subjectivity in Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese, 1980) provides a useful starting point here. He emphasises that the boxing sequences function as a disturbing but powerful articulation of the boxer’s subjectivity, by representing his embodied experience in the ring (“Art and Genre”). Woodward adds that depictions of the material, flesh-and-blood body are significant in providing the spectator with a sense of immediacy, which corroborates more general concerns about “reality and authenticity” in the boxing film, including “the socio-economic reality of the boxers’ lives and the authenticity of boxing itself” (127; emphasis added). As she notes, claims to realism in the boxing film are tied to, and are manifested in, depictions of the “corporeal materiality” of the boxer (131).

What sets Million Dollar Baby and Die Boxerin apart from the relatively small number of other (recent) female boxing films, and perhaps more generally from other cinematic representations of female bodily performance, is the realist and visceral representation of the boxer’s corporeality. [6] The boxing performances by Joe (Katharina Wackernagel) in Die Boxerin and Maggie (Hilary Swank) in Million Dollar Baby are characterised by a sense of authenticity that is variously grounded in the actresses’ bodily transformations and physical capabilities as well as the (visual, auditory and embodied) access we, as spectators, have to those bodies. In both films, the boxers’ corporealities are foregrounded through an emphasis on sweat, glistening on the skin, running down their bodies, leaving stains on their clothing, making strands of hair stick to their foreheads; through the sound of the violent impact of punches, of cracking bones and of heavy breathing and panting; through close-ups of muscles in motion and of bruised and bloodied faces. These are material, flesh-and-blood bodies, with weight and substance; bodies that labour and that show the effects of that labour; bodies that sweat, bleed and smell. In what follows, I argue that the boxing sequences in Die Boxerin provide an articulation of the protagonist’s corporeal struggle for the embodiment of a unified sense of self, while inviting from the viewer embodied, kinaesthetic and muscular empathy with the phenomenal experience of this struggle. The boxing sequences in Million Dollar Baby, on the other hand, despite containing more explicit representations of violence and bodily injury, provide an articulation of Maggie’s corporeality as mediated, in embodied terms, by her coach, Frankie (Clint Eastwood). In doing so, I will argue, they undermine the film’s subversive potential.

Boxing in Context

Following the conventions of the genre, Die Boxerin depicts the boxing and social worlds as separate but intertwined. Dramatic conflicts originate in the broader social-cultural context, rather than primarily in the gym or ring (as in Million Dollar Baby). The boxing sequences serve as a bodily expression of these conflicts and are often tied to particular narrative events. Die Boxerin establishes a very specific (sexed, gendered, raced and classed) identity for its boxing protagonist at the outset by emphasising her disadvantaged and marginal social existence. In the early sections of the film boxing plays a relatively minor role as Deus concentrates on situating the female protagonist in a very particular (East German, working-class, rural) milieu. It is only when this context is established that the focus shifts to Joe’s involvement in boxing. Die Boxerin also diverges from the conventions of the male boxing film in its emphasis on the protagonist’s alienation from her ambiguously gendered body, which ultimately provides the narrative justification for her engagement in boxing. In contrast, Million Dollar Baby presents a narrative situated first and foremost within the boxing context, with only sparse depictions of the social world used to frame Maggie’s disenfranchised existence in very broad, abstract and almost timeless terms. The boxing context in Million Dollar Baby stands in, metaphorically, for the world more generally, recalling Oates’s assertion that for the boxer boxing is not like life; it is life.

In Die Boxerin, the protagonist’s search for a unified sense of self has a particularly spatial and bodily dimension from the outset. The pervasiveness of bodily movement, including recurring sequences of Joe on her moped, serves as an articulation of restlessness. The film links Joe’s movement to her unconventional embodiment of gender and her inability to “fit in”. This is highlighted in a sequence that shows her in the company of three other female characters in a local pub. Their speech and clothing mark them as distinctly (and stereotypically) rural East German and working class. Joe’s marginalisation within the (already marginalised) community is underlined through her placement within the frame. She is positioned behind the conventionally feminine characters that talk about Joe but exclude her from the conversation as if she did not, in fact, reside in the same space. They ridicule her gender-inappropriate demeanour and jokingly question her heterosexuality and biological femaleness. This is one of numerous occasions in which the film draws critical attention to common equations of gender performativity with the physical body and sexuality and to the limitations of binary understandings of sex, gender, and desire. Narratively, this is foregrounded through Joe’s engagement in both heterosexual and lesbian encounters, with Mario (Devid Striesow) and Stella (Fanny Staffa), respectively.

The pub sequence also draws attention to the awkwardness with which Joe inhabits her body, when she hits her head against the bar to the amusement of the other women. She is literally unable to inhabit her surroundings—spaces that are marked by strict gender policing—without bumping into restrictive and inhibiting boundaries. More generally, the film also highlights the embodied and spatial dimensions of Joe’s responses to (narrative) conflicts and tensions that arise from her unintelligible embodiment of gender. Joe’s rash reactions to insults and humiliation (for instance when she is unjustly accused of stealing, mistaken for a man, or fired from her job) are embodied and corporeal; her clashes with other characters are physically violent—and such behaviour gets her into even more (gender) trouble.

The kind of elaborate narrative justification we find in Die Boxerin is noticeably absent in Million Dollar Baby. The film lacks the careful construction of the protagonist’s socially situated identity (although there are references, albeit rather generalising ones, to Maggie’s “white trash” background) and the inscription of a “natural” disposition for aggression and violence is missing altogether. Maggie is depicted as isolated and devoid of meaningful interactions in social spaces outside the gym, which means that the unconventional embodiment of gender associated with her engagement in boxing loses some of its unsettling significance (within the diegetic world of the film). In fact, the key relationships Maggie develops are with Frankie and Scrap (Morgan Freeman), the African-American handyman of the gym, whose visual/bodily marginalisation is contrasted with the all-knowing and omnipresent nature of his voiceover throughout the film. Both of these relationships with older male characters are developed within the boxing gym, thus situating Maggie’s character almost exclusively in relation to, as we will see, troubled working-class and/or ethnic-minority masculinities.

In Million Dollar Baby Maggie enters the film out of nowhere, when she appears in a boxing arena, emerging from a dark hallway. Her appearance lacks (narrative) contextualisation and the only marker of identity highlighted is Maggie’s androgyny: her plain, make-up-less and only partly lit face, her baggy sweatshirt, the hood pulled over her head, her slightly smiling but otherwise mysterious and nonspecific facial expression. Swank’s previous role as the transgendered Teena Brandon/Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999) is usefully recalled here. The ambiguities surrounding the embodiment of sex, gender and sexuality of Swank’s character in that film arguably allow her performance in Million Dollar Baby to be associated with a similar sense of contradiction. The queer potential of the film (which, as I will argue below, is variously disavowed) lies both in the representation of a “musculine” (Tasker 149) female body engaged in convincing boxing performances as well as in the casting of Swank and the inter- and extra-textual references conveyed by her star persona. It is worth noting here that Million Dollar Baby provides a particularly explicit articulation of the doubly performative nature of boxing in cinema. The foregrounding of Maggie’s bodily transformation and powerful physicality invites the spectator to contemplate the muscular body of Hilary Swank, the Hollywood star. The considerable publicity that surrounded the actress’s training regime and muscle gain added a sense of authenticity to her boxing performances and highlighted the corporeal dimensions of gender performativity. However, these also tended to frame Swank’s “corporeal shape-shifting” (Williams, “Ready for Action” 171) as a beauty project in which Swank’s “embodied transformation is sexualised” (Woodward 141) in very conventional, heteronormative terms (for instance, we learn that Swank’s husband is “totally knocked out” by her newly toned “butt” (Woodward 141)).

Box!

In Die Boxerin, the physical activity of boxing is linked more directly to the protagonist’s attempts to negotiate her twisted embodiments of gender. The first boxing scene directly follows Joe’s humiliating encounter in the pub. Joe returns home on her moped and enters a wooden shed that contains an old boxing bag. The scene consists of one long take that frames Joe in a medium shot as she hits the bag until she is too exhausted to continue. Joe is not fighting an opponent or training to prepare for a fight. Instead, and departing from the conventions of the genre, boxing is presented here as a way of working through the corporeal and emotional tensions resulting from her unintelligible bodily existence. It is introduced as an intimately personal activity, removed from institutionalised sport and athletic achievement, as well as from the empowering potential it carries in Million Dollar Baby. The boxing activity in this first scene can be read as a desperate attempt to reshape and reorientate the body. Joe’s grimacing face and the guttural sounds she makes foreground the body’s tense materiality; her poorly fitting clothes underline the sense that her body does not “fit”, that it is alien, object. To paraphrase Ahmed, Joe is not “at home” in her own skin, and this sequence deftly presents us with an articulation of her unsuccessful attempt to get “in touch” with her body (Ahmed 9). In turn, the viewer is directly and powerfully confronted with the unsettling significance of her bodily performance.

Figure 1: Joe’s “painstaking labour”. Die Boxerin (Catharina Deus, 2004). Sony, 2006. Screenshot.

The framing of the sequence generates a paradoxically alienating proximity that is deeply troubling. In a lengthy static take, Joe is framed in medium shot as she hits the boxing bag with ever-increasing intensity. The emotional tone changes from sadness to anger: Joe’s ever more powerful punches and extensive, wide-reaching movements, her distorted facial expressions, the tensions around her mouth and guttural panting, provide a visceral articulation of her attempt to release and give expression to bodily tensions and pain. The sequence ends with a medium close-up of Joe’s face as she breathes heavily, wiping sweat off her forehead and removing strands of hair from her mouth with her gloved hand. We witness her facial expression reverting to one of desperate sadness, with her trembling lip indicating the muscular effort required to hold back tears. The sequence conveys, in embodied and affective terms, the phenomenal experience of lack of “fit” that Ahmed describes: “For bodies to arrive in spaces where they are not already at home, where they are not ‘in place’, involves hard work; indeed, it involves painstaking labour for bodies to inhabit spaces that do not extend their shape” (62; emphasis added). The viewer is powerfully aligned with the affective shifts embodied by Joe, with her “painstaking labour”. The sequence also expresses Joe’s inability to ultimately effect a more comfortable and less painful “fit”—the release is only temporary, and the effort it takes to resist the pressures of normative phenomenal space seems beyond her bodily capabilities.

Despite the tensions depicted, the shed’s old, wooden walls, minimal lighting and lock that allows Joe to shut herself off from the outside world denote it as a safe and arguably queer space. It provides temporary release from the normative sociocultural pressures that Joe experiences as overwhelming and painful. Its queer significance is reaffirmed when Stella, with whom Joe has a sexual encounter, is welcomed into this space in a scene that takes place after a night out at the local club. It is within this space that the two are free to engage in intimate conversation and play fighting/boxing, foregrounding the embodied dimension of their queer relationship (even outside their sexual encounter). However, the shed is a precariously utopian space and the light shining in through the cracks and holes in the porous walls serves as a reminder of the powerful and virtually all-encompassing reach of the heteronormative pressures and tendencies that characterise the other spaces in the film.

When Joe’s boxing activity moves from the privacy of the shed into the homosocial and hypermasculine sphere of the boxing gym it takes on markedly different significance. The boxing gym is a highly regulated space, emphasising discipline and regimented training. Joe’s first boxing lesson in the brightly lit gym opens with a two-shot of Joe copying movements that her trainer, Igor (Martin Brambach), demonstrates for her. There is a focus on her concentrated face as Igor grabs Joe’s shoulders and physically guides her movements so they become fluid and smooth. Joe’s movements are awkward and tense, reasserting her alienation from, and paradoxical unfamiliarity with, the powerful physicality of her body—as Igor points out, she needs to find her “centre of gravity” and reorientate herself. As in Million Dollar Baby, the raw but powerful physicality of the female boxer is contrasted with the ageing physicality of the male trainer. He has the knowledge and experience but his deteriorating body does not allow him to step into the ring.

Joe’s presence in the gym is met with overt disapproval by the male boxers and her transgression into the sanctity of this homosocial space does not remain unpunished. After one of the early training sequences, three male boxers, including Ali (Marc Richter), corner Joe in the shower room, a cold and bleak space as underlined by the hard, unflattering light and the harsh, echoing sound of splashing water. Joe is naked and the three men are fully clothed. Two of the boxers restrain Joe as Ali announces that they are here to “check something”. He forcefully pushes Joe’s bare feet apart with his heavy boots and then kneels on the ground. A medium close-up of his face shows him staring at Joe’s genital area, in a violent intrusion of her body. Even though the viewer is denied the visible evidence the male boxers are looking for, the audiovisual framing of the scene means that we are powerfully implicated in the disturbing violation of her body. The focus quickly shifts back to Joe, as close-ups of her face convey surprise, fear and vulnerability, while the soundtrack captures the breathy and wincing sounds that escape her body as she is pushed around by the boxers. Importantly, Joe’s face remains centre stage while the male boxers occupy the margins of the frame, aligning the viewer with Joe’s bodily and affective experience.

The scene’s portrayal of violence is harrowing (and indeed reminiscent of a similar scene in Boys Don’t Cry). It adds to the tensions surrounding the later sparring match between Joe and Ali, turning it into a bodily manifestation of Joe’s struggle against the repressive gender norms associated with hetero-patriarchal structures, spaces and bodies. Ali retains the upper hand and Joe leaves the ring exhausted, with a bloody nose and black eye. Significantly, boxing is virtually absent from the narrative after this sparring match—a manifestation of Joe’s giving in to the overwhelming pressures and “straightening” forces of normative phenomenal space (Ahmed 137). Instead, Joe’s relationship with Mario becomes the central narrative focus.

In contrast to the conventions of the genre, the narrative mapping of athletic progress and bodily transformation is noticeably absent in Die Boxerin, reemphasising that the significance of Joe’s engagement in boxing lies not in the meaning it carries as an institutionalised and competitive activity but, rather, in the recentring of, and reconnection with, the self that boxing facilitates. The relative lack of direct visual access to Joe’s body in the film means that we are less explicitly positioned in relation to the materiality and transformation of that body. This is in marked contrast to Million Dollar Baby, in which Maggie’s improvement as a boxer is accompanied by, and at least partially articulated through, an increased visual emphasis on her powerful physicality (as baggy clothing is replaced by increasingly fitted and revealing outfits that allow visual access to muscles, for instance). While the visual spectacle of bodily transformation is not heavily emphasised in Die Boxerin, the final boxing sequence returns the materiality of the body to centre stage.

This final bout, introduced through the caption “3 months later”, is somewhat removed from the overall narrative and does not provide resolutions for the conflicts addressed within the film. Instead, it is characterised by an explicit, primarily aural, emphasis on the materiality of the body, for example through Joe’s guttural panting as she receives punches to her stomach. At certain points, we see the mostly female spectators covering their eyes, underlining the contradictory viewing pleasures provided by the film itself and recalling Woodward’s assertion of the paradoxical draw of violent display in boxing. It is worth noting that in this sequence Stella is the only recognisable character in the otherwise anonymous crowd that watches the fight. Close-ups of Stella gazing at the spectacle of Joe fighting reassert the queer implications of women’s boxing and of the embodied spectatorial engagements the female boxing body provides.

Figure 2: Joe in the ring. Die Boxerin. Sony, 2006. Screenshot.

At one point, the camera takes up Joe’s position in the ring (a ubiquitous technique of the genre), articulating her perspective of the action as she receives a heavy blow to the side. Joe’s skewed perception and disorientation are articulated through a switch to slow motion and distorted sound patterns, which provide an aural articulation of the feeling of blood rushing to her head, her pulse pounding in her ears. Towards the end of the fight, the diegetic noise is completely drowned out and replaced by very slow and melodic nondiegetic choral music. Together with the increasingly stylised slow-motion framing, this overlays the sequence with an abstract and paradoxically transcendental tone. Joe’s heavy breathing is audible in addition to the music but the echoing sounds are strangely disconnected from their source, her body. The foregrounding of both (the experience of) the material body and an alienating distance from its corporeality indicates that the conflicts concerning twisted embodiments of sex, gender and sexuality addressed throughout the film cannot be resolved in the “realm of flesh and blood” (Altman 63). The film’s ending is ambiguous in the sense that it lacks a reassuring utopian celebration and solution for prevalent sociocultural anxieties around gender transgression. This suggests, on the one hand, that Joe’s non-normative embodiment remains a (generic) problem. However, the film also opens up a space of possibility for alternative configurations of gender and desire through its refraining from traditional containment strategies, such as the integration into heteronormativity that we see in other examples of the genre, such as Girlfight, or, more (melo)dramatically, the death of the female boxer in Million Dollar Baby.

As has been noted, Million Dollar Baby provides a much more explicit visual foregrounding of the boxer’s corporeality, and the unglamorous, unfeminised and desexualised depiction of the female (boxing/movie) star certainly disrupts normative gender binaries and thus carries queer connotations, especially in the context of Hollywood cinema and its narrowly heteronormative representational conventions around female protagonists’ appearances and (narrative and visual) functions. However, the film does not open up the kinds of twisted points of engagement that I have identified in relation to Die Boxerin. Rather, Million Dollar Baby articulates conventionally “straightforward tendencies” (Ahmed 77) in embodied, kinaesthetic and affective terms.

The training sequences in the opening part of the film function primarily as visual articulations of the marginality of Maggie’s existence. In one scene, we see Maggie hitting the punching bag by herself in the empty gym late at night. Aligning the viewer with Scrap’s point of view, Maggie is framed by an extreme long shot through the ropes of the ring and becomes visible as a small dark figure against the whiteness of the wall behind her, emphasising her two-dimensional, shadow-like existence. As Maggie circles the bag, Scrap’s voiceover comments that “if there is magic in boxing, it’s the magic of fighting battles beyond endurance, beyond cracked ribs, ruptured kidneys, and detached retinas. It’s the magic of risking everything for a dream that nobody sees but you”. The empowering potential of boxing is explicitly related here to the bodily experience of violence and to the ability to overcome pain, while the description of injury is, paradoxically, spoken in a warm, soft voice. The film’s signature slow and melodic score accentuates this juxtaposition as does the artistic quality of the image, which infuses the violence and brutality of boxing with a sense of aesthetic beauty. Spectatorial contemplation and distance, rather than an embodied engagement with the more visceral aspects of the bodily performance (here visually marginalised), is thus invited (Woodward; Oates).

Million Dollar Baby differs significantly from Die Boxerin in that the boxing sequences consist primarily of sparring matches and bouts, portraying boxing as a competitive and violent interpersonal encounter. There is a general tendency for Maggie’s success in the ring to be depicted as crucially dependent on Frankie’s presence outside the ring—narratively, visually and in terms of the embodied engagements facilitated by the film. Her struggle for subjectivity and agency is mediated by Frankie, and plays out in relation to his troubled masculinity. This is illustrated in her first sparring match, in which the (visual) focus is on Frankie’s disinterest and lack of attention as he sits on a bench outside the ring, reading a book. This is also emphasised in a short fight scene that opens with the recurring two-shot of Maggie and Frankie in the corner of the ring. As the bell rings, Maggie runs past the camera and out of the frame, approaching the centre of the ring. The action behind the camera is expressed by the thumping noises of punches thrown, the satisfied look on Frankie’s face, the cheering of the crowd and Maggie’s return back into the frame and into the corner. Frankie’s experience of watching the fight is clearly privileged over Maggie’s experience of being physically involved.

Additionally, Frankie’s embodied experience of Maggie’s struggle tends to be emphasised as reaction shots show Frankie immersed in the action himself, mirroring/anticipating Maggie’s moves—a poignant articulation of the kind of embodied engagements available to the cinematic spectator. Frankie’s mirroring of Maggie’s action is significant as it contrasts Maggie’s/Swank’s powerful physicality with Frankie’s/Eastwood’s ageing and fragile body. Conflicts around bodily deterioration that are central to the boxing film genre (Grindon, Knockout) are therefore played out in relation to Frankie’s/Eastwood’s body (Modleski; Woodward) and the boxing sequences can be read as a corporeal dramatisation of his ageing and troubled masculinity. The kind of sensuous and kinaesthetic contact with the queer embodiment of the female boxer that is enabled by Die Boxerin is thus sidelined in Million Dollar Baby.

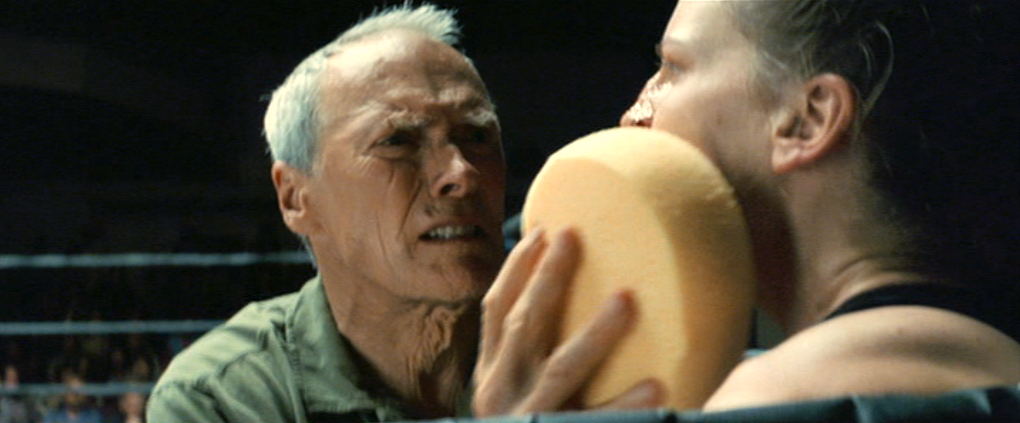

Figure 3: Frankie’s point of view. Million Dollar Baby (Clint Eastwood, 2004). Warner Home Video, 2005. Screenshot.

Such marginalisation is vividly asserted in a boxing sequence that shows Maggie struggling against a more capable opponent. The action is framed from outside the ring, interrupted by reaction shots of Frankie, until the camera moves inside the ring to emphasise the brutality of a blow that hits Maggie in the face, breaking her nose. The loud cracking sound, as well as the crowd’s gasping in horror, underlines the severity of the punch. The film thus provides the kind of visceral articulation of injury and bodily pain that is found in certain male boxing films such as Raging Bull and Cinderella Man (Ron Howard, 2005) but that is largely absent in Die Boxerin.

Figures 4 and 5: Maggie’s broken nose and Frankie’s pain. Million Dollar Baby. Warner Home Video, 2005. Screenshots.

As Frankie wipes blood off Maggie’s face, their interaction is framed by close-ups from various angles, the majority of which focus on Frankie’s distraught face. The moment of central significance is a close-up of Maggie’s face, distorted from pain and partially obscured by Frankie’s hand, as he forcibly pushes her broken nose back in place. The loud cracking sounds of grinding bones and Maggie’s grunting provide a disturbingly visceral articulation of her damaged physicality which is, however, mediated by an emphasis on the emotional intensity of Frankie’s reaction. The affective centre of gravity, “the zero point of orientation, the point from which the world unfolds, and which makes what is ‘there’ over ‘there’” (Ahmed 8, citing Husserl), is Frankie. The queer female body remains a straightforward (visual) spectacle, rather than a point of “contact” for embodied spectatorial engagements of the kind that Barker has explored.

The most striking assertion of these embodied tendencies takes place in the climactic fight sequence, after which boxing is completely erased from the narrative. Maggie’s opponent is Billie “The Blue Bear”, a “former prostitute from East Berlin”, who has an overpowering and threatening physical presence and a reputation as a dirty fighter. The juxtaposition of the innocent, childlike and desexualised Maggie with the square-jawed, immoral, sexually transgressive, monstrously masculine Billie, played by professional kickboxer Lucia Rijker, functions to assuage the potentially transgressive implications of Maggie’s character. While, as already noted, Maggie’s muscular physique and engagement in boxing carry subversive potential, this appears negligible when contrasted with the multiple transgression of heteronormativity embodied by Billie “The Blue Bear”. The threatening and arguably monstrous implications of Billie’s character hinge on the highlighting of racial difference in this violent encounter: while she has previously encountered dark-skinned opponents, the lighting used in this scene emphasises Maggie’s translucent white skin, contrasted with the dark skin of The Blue Bear. It may be argued that here the Blue Bear character functions as a “straightening device” (Ahmed 137) in relation to Maggie, who is explicitly aligned with the whiteness of normative phenomenal space. Ahmed argues that phenomenology allows us to “begin the task of making ‘race’ a rather queer matter” (112), and points to the ways in which nonwhite bodies disrupt the straightforward orientations of phenomenal space. Billie’s gender transgression can therefore be read as doubly disorientating and much more twisted than Maggie’s (in all senses of the term).

The fight sequence also reasserts Maggie’s embodied dependence on Frankie who she increasing “turns towards” and “attends to” as the fight progresses (Ahmed 29). The exchange of helpless glances between Maggie and Frankie foregrounds his powerlessness at the side of the ring. The central drama evolves not so much around Maggie’s unequal struggle with her opponent but around Frankie’s bodily inability to interfere. It is Frankie’s loss of control and agency, his “inhibited intentionality” (Young 145), that is represented as deeply troubling and that we are encouraged to empathise with kinaesthetically. This manifests itself most dramatically in the film’s climactic moment that takes place during a break between rounds: an extremely brief point-of-view shot from Maggie’s perspective shows Billie’s glove rapidly approaching the camera/Maggie’s face. The subsequent frontal close-up shows Maggie as, completely unprepared, she receives the heavy blow. Significantly, this is followed by a shot of Frankie’s face and a cut to a slow-motion, low-angle point-of-view shot depicting Frankie’s registering of Maggie’s head snapping violently to the side, with sweat and spit splashing from her distorted face as she loses consciousness. The diegetic noise gives way to wind-like sounds, providing a highly subjective articulation of Frankie’s sensory experience of witnessing the incident. This contrasts, in insightful ways, with the framing of the climatic fight sequence in Die Boxerin. Despite the similar shift in the soundscape—from the realist, and perhaps “objective”, articulation of the sounds and noises of the boxing fight, to a highly subjective portrayal that provides the spectator with a “sense” of the characters’ experience—our corporeal alignment in Die Boxerin is with Joe, while Million Dollar Baby aligns our “sensuous empathy” with Frankie (Barker 77).

The incident leaves Maggie paralysed from the neck down, unable to even breathe on her own. Ultimately, Maggie’s experience of her body as strong, powerful and capable is replaced by utter alienation and a complete lack of control. She has no bodily sensations, and needs others to move her body for her. With boxing completely removed from the narrative at this point, the film’s melodrama revolves around Frankie’s moral struggles (Modleski; Woodward), while Maggie’s corporeal experience of immobility is marginalised. This is the case even when Maggie loses her leg through amputation, and when she bites her tongue in a desperate effort to take her own life—a last attempt to enact bodily agency. The emotional melodrama reaches its peak when Maggie asks Frankie to end her life as, lacking agency entirely, she is unable to do so.

And the Winner Is…

In the context of the functional nature of genres as attempts to resolve particular sociocultural conflicts, the recent emergence of the female boxing film points to what might be viewed as a relatively new sociocultural problem, linked to the increased cultural visibility of alternative embodiments of sex/gender (by, for example, female boxers) and the serious challenge to binary conceptions “in a sea of discursive uncertainty” (Woodward 3). The increased visibility of “convincing” boxing performances by female characters and the embodiment of strong, powerful and “musculine” (Tasker 149) physicalities by female stars/actresses can be read as part of the reconstitution of gender norms for which the boxing context provides particularly suitable possibilities. The materiality of women’s muscular and powerful bodies is foregrounded in various ways in Die Boxerin and Million Dollar Baby and both films challenge normative conceptions of sex, gender and sexuality to various extents—however, they are also characterised by various forms of containment.

This article’s focus on embodiment and corporeality, and on the kinds of embodied—straightforward as well as twisted—engagements facilitated by the female boxing film, points to the ways in which cinema’s incorporation of different orientations and modes of embodiment might play into the unhinging and/or sedimentation of normative modes of embodied existence. What is highlighted is that the queer implications of certain films, and perhaps cinema more generally, do not necessarily reside in particular story lines or characters, no matter how queer they might “look”. Ahmed’s phenomenological account of queerness as a twisted mode of being-in-the-world, as a way of inhabiting space that clashes with and presses against the straightforward contours of normative phenomenal space, has allowed me to locate a sense of queerness in relation to filmic incarnations of bodies and/in space. By accounting for the ways in which the lived experiences of queerness might be embodied and/or disavowed in cinematic terms, this argument points to more general conceptual and methodological possibilities opened up by queer phenomenological approaches to film.

Notes

[1] It is important to note that the star persona of Eastwood has been read as the embodiment of (a conservative) Hollywood masculinity. The changes in the kinds of masculinities embodied by Eastwood over the last five decades (both by the actor and the characters he has played) can usefully be read against the backdrop of changing gender relations and associated threats to hegemonic masculinity. Modleski identifies much of Eastwood’s most recent directorial output, including Million Dollar Baby, as male melodramas/weepies, characterised by a sentimental and melancholy register, mourning the loss of a masculine ideal.

[2] Die Boxerin was promoted as “Das deutsche Million Dollar Baby”(“The German Million Dollar Baby”), which is slightly paradoxical considering the differences between the two films alluded to here and explored further in this article.

[3] Boyle at al. criticise Million Dollar Baby for not accurately reflecting the reality of female boxing.

[4] In his book-length study, Contesting Identities: Sports in American Film, Baker points to (the history of) the boxing film as an articulation of the shifting class and race/ethnic relations in the U.S. In it he traces the ways in which different subordinate groups of male youths (Irish, Italian, Eastern European, Jewish, African American and Latino) have predominated in the boxing world at various points in the late nineteenth and twentieth century, in an attempt to overcome socioeconomic barriers and transcend the constraints of race and class. However, in the vast majority of cases, as he notes, boxing only presents the mere illusion of empowerment and functions to keep class and racial hierarchies intact through the (lasting) damage inflicted on the boxer’s body and the lack of marketable skills cultivated in the boxing context. “Only a select few who have entered the ring have attained wealth and fame … Joyce Carol Oates concisely describes the pyramidal structure of prizefighting when she says that it has ‘a limitless supply of losers, but … very few stars’” (101). A consideration of women’s increased participation in boxing (and increased visibility in the boxing film) in this context highlights the contradictory implications of this tendency.

[5] Ahmed “turn[s] to the etymology of the word ‘queer’, which comes from the Indo-European word ‘twist’. Queer is, after all, a spatial term, which then gets translated into a sexual term, a term for a twisted sexuality that does not follow the ‘straight line,’ a sexuality that is bent and crooked” (67).

[6] The additional exception here is Girlfight, which provides a similarly convincing and visceral depiction of the female boxer, aided considerably by Michelle Rodriguez’s muscular and energetic performance as Diana Guzman.

References

1. Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. London: Duke U.P., 2006. Print.

2. Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical. Bloomington: Indiana U.P., 1987. Print.

3. Auerbach, Jonathan. Body Shots: Early Cinema’s Incarnations. Berkeley: California U.P., 2007. Print.

4. Baker, Aaron. Contesting Identities: Sports in American Film. Chicago: U. of Illinois P., 2006. Print.

5. Barker, Jennifer M. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: California U.P., 2009. Print.

6. Boyle, Ellexis, Brad Millington, and Patricia Vertinski. “Representing the Female Pugilist: Narratives of Race, Gender, and Disability in Million Dollar Baby”. Sociology of Sport Journal 23 (2006): 99–116. Print.

7. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge, 1999. Print.

8. ---. “Athletic Genders: Hyperbolic Instance and/or the Overcoming of Sexual Binarism”. Stanford Humanities Review 6.2 (1995). Web. 2 June 2014. <http://www.stanford.edu/group/SHR/6-2/html/butler.html>.

9. Caudwell, Jayne. “Girlfight: Boxing Women”. Sport in Society 11.2–3 (2008): 227–39. Print.

10. Cook, Pam. “Masculinity in Crisis? Tragedy and Identification in Raging Bull”. Screen 23.3/4 (1982): 39–46. Print.

11. Deus, Catharina, dir. Die Boxerin [About a Girl]. 2004. Sony, 2006. DVD.

12. Eastwood, Clint, dir. Million Dollar Baby. 2004. Warner Home Video, 2005. DVD.

13. Fojas, Camilla. “Sports of Spectatorship: Boxing Women of Color in Girlfight and Beyond”. Cinema Journal 49.1 (2009): 103–15. Print.

14. Grindon, Leger. Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. Jackson: Mississippi U.P., 2011. Print.

15. ---. “Art and Genre in Raging Bull”. Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. Ed. Kevin Hayes. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P., 2005. 19–40. Print.

16. Hargreaves, Jennifer. “Women’s Boxing and Related Activities”. Body & Society 3.4 (1997): 33–49. Print.

17. Heywood, Lesley, and Shari Dworkin. Built to Win: The Female Athlete as Cultural Icon. Minneapolis: U. of Minnesota P., 2003. Print.

18. Howard, Ron, dir. Cinderella Man. Universal, 2005. Film.

19. Husserl, Edmund. Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, Second Book. Translated by Richard Rojcewicz and André Schuwer. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1989. Print.

20. Kusama, Karyn, dir. Girlfight. Green/Renzi; Independent Film Channel, 2000. Film.

21. Lindner, Katharina. “Bodies in Action: Female Athleticism on the Cinema Screen”. Feminist Media Studies 11.3 (2011): 321–45. Print.

22. ---. “Fighting for Subjectivity: Articulations of Physicality in Girlfight”. Journal of International Women’s Studies 10.3 (2009): 4–17. Print.

23. Modleski, Tania. “Clint Eastwood and Male Weepies”. American Literary History 22.1 (2010): 136–58. Print.

24. Oates, Joyce Carol. On Boxing (1987). London: Harper Perennial, 2006. Print.

25. Peirce, Kimberly, dir. Boys Don’t Cry. Fox Searchlight, 1999. Film.

26. Rich, B. Ruby. “Take it Like a Girl”. Sight & Sound 11.2 (2001): 16–19. Print.

27. Scorsese, Martin, dir. Raging Bull. United Artists, 1980. Film.

28. Sklar, Robert, and Tania Modleski. “Million Dollar Baby: A Split Decision”. Cineaste 30.6 (2005): 6–11. Print.

29. Streible, Dan. Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema. Berkeley: California U.P., 2008. Print.

30. Tasker, Yvonne. Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre, and the Action Cinema. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

31. Williams, Linda. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure and the “Frenzy of the Visible”. Berkeley: California U.P., 1989. Print.

32. Williams, Megan. “In the Ring with Mildred Pierce: Million Dollar Baby and Eastwood’s Revision of the Forties Melodrama”. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory 67.1 (2011): 161–86. Print.

33. Wood, Robin. “Raging Bull: The Homosexual Subtext”. Movie 31/32 (1986), 108–14. Print.

34. Woodward, Kath. Boxing, Masculinity and Identity: The “I” of the Tiger. London: Routledge, 2007. Print.35. Young, Iris Marion. “Throwing like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility and Spatiality”. Human Studies 3.2 (1980): 127–56. Print.

Suggested Citation

Lindner, K. (2014) 'Corporeality and embodiment in the female boxing film', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 7, pp. 6–23. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.7.01.

Katharina Lindner is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Stirling. Her research interests are interdisciplinary and include gender and queer theory, feminist film and cultural criticism, film phenomenology, as well as media and sport. She has published work on athleticism and cinema, dance in film, sport and (post)feminism, as well as on bodily performance and embodiment and/in film. Her current research engages specifically with queer critiques of traditional (film) phenomenology and explores questions of embodiment, sensuousness and affect in relation to a variety of film bodies.