To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation

Helen Haswell

Pixar Animation Studios has been at the forefront of cutting-edge digital animation for over twenty-five years. The phenomenal success of Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995), the world’s first fully computer-generated animated feature film, saw the “widespread popularization of 3D computer animation technologies in both animated and live action cinema” (Montgomery 7). Not only has the technology developed by Pixar become an industry standard for filmmaking, but the studio’s aesthetic style epitomises contemporary mainstream animation. While Colleen Montgomery argues that the technology pioneered by Pixar has “displaced hand-drawn traditions in mainstream American animation” (8), we are now witnessing Pixar’s experimentation with traditional 2D animation techniques and with textures that are organic and imperfect. We are familiar with the use of the term “organic” pertaining not only to the body, but also in relation to all that is more natural and less artificial. I will be using the term “organic aesthetic” to describe a tendency that has recently emerged in digital animation and that relates not just to what is hand drawn, but also to a look that is altogether non-artificial, analogue and nostalgic. The emergence of a more organic aesthetic is most evident in Pixar’s short films Day & Night (Teddy Newton, 2010) and La Luna (Enrico Casarosa, 2011). This article will argue that the organic aesthetic embraced in these short films has in turn influenced the style of Walt Disney Animation’s Paperman (John Kahrs, 2012) and Get a Horse! (Lauren MacMullan, 2013). Pixar has pushed the boundaries of computer-generated animation to create digital images that resemble hand-drawn artwork, highlighting a nostalgic trend for the analogue, which, as will be demonstrated later, broadly characterises contemporary media. In order to engage with these recent developments, this article will explore the aesthetic and methods employed in Pixar’s short films, also drawing comparisons between La Luna and Paperman, and Day & Night and Get a Horse!. The first section of the article will outline the significant technological developments that have facilitated the emergence of an organic aesthetic within digital animation, while the second section will consider how nostalgia informs a common preference for a more traditional look. Finally, this article will examine how the convergence of 2D and CG animation techniques represents and encapsulates the creative partnership and collaboration between Pixar and Disney Animation Studios.

To Infinity…: Pixar’s Innovation

Pixar’s cutting-edge approach emerges in particular from its long-standing tradition of short films, which form the basis for the studio’s research and development. The shorts that have been produced by the studio since the late 1980s have enabled Pixar to develop ideas and advance technical capabilities. La Luna, in particular, marks a pivotal shift within Pixar’s short film canon by demonstrating an organic aesthetic through textures that appear manmade and flawed. The film, which was released theatrically alongside Brave (Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman, 2012), is a coming-of-age tale about a young boy who joins his father and grandfather for the first time as they reveal their family’s unusual line of work—clearing fallen stars from the moon. The film employs hand-drawn art and watercolour backgrounds to challenge the sleek contemporary appearance of mainstream animation. By juxtaposing digital methods with an analogue aesthetic, Pixar not only highlights a preference for a more traditional look, but also underlines the technological advancements that have enabled CG animation to achieve a more organic image. An understanding of these key developments, which can be traced through Pixar’s short film history, is essential in order to contextualise the aesthetic choices made for La Luna.

Pixar began making short films as a way to explore and advance technology with the goal of producing a completely computer-animated feature-length film. In its early days these short films promoted the work of the fledgling company, becoming an integral part of Pixar’s development as a film studio. Following the success of Toy Story it was decided to continue this tradition as a way of promoting R&D, developing in-house talent (and retaining it in-between feature film productions), and experimenting with ideas and techniques without committing to a full-length feature. Pixar’s first theatrical short, Geri’s Game (Jan Pinkava, 1998), in which the protagonist plays a game of chess against himself, was originally released alongside A Bug’s Life (John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton, 1998), the studio’s second full-length animated film. Ever since, every Pixar film has an accompanying short that plays before the main feature.

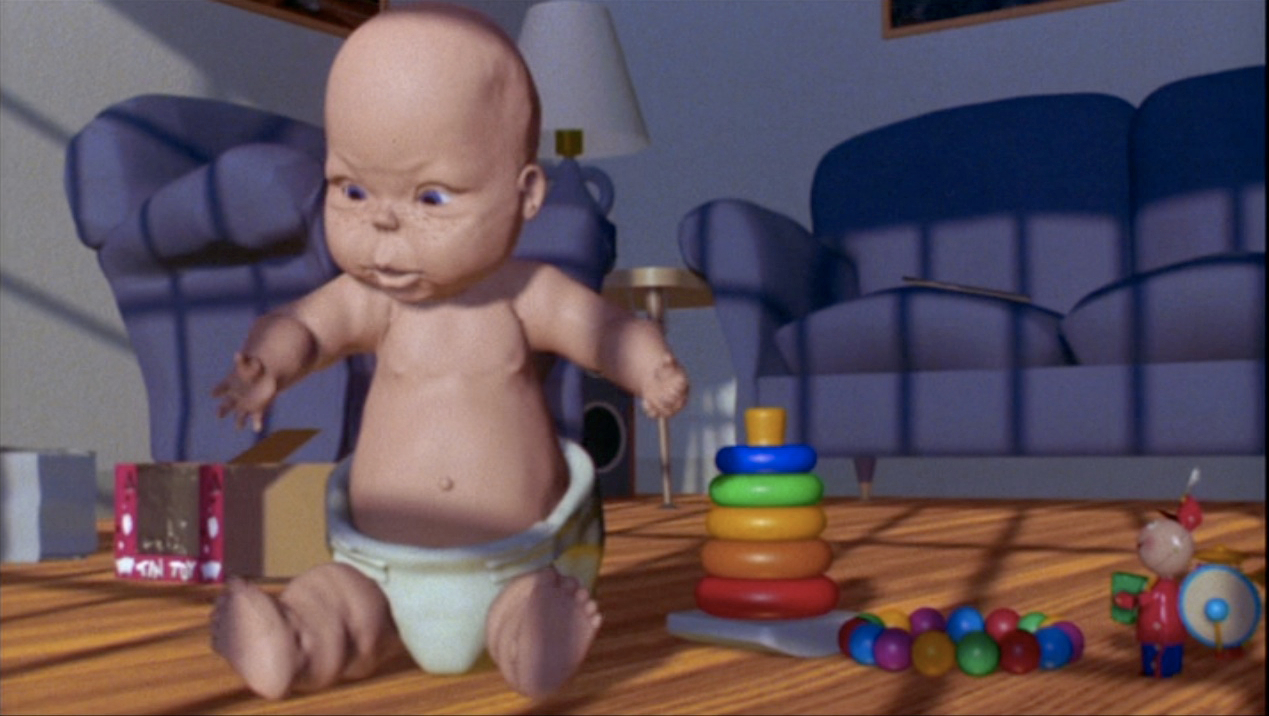

In Pixar: 25 Magic Moments (Richard Mills, 2011), a documentary marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of Pixar Animation Studios, John Lasseter says of the studio’s processes that “art challenges the technology [and] technology inspires the art”, thus highlighting Pixar’s tendency to choose a subject matter that lends itself to the medium, while simultaneously testing and stretching the limits of CG animation. The studio embraced the early limitations of the medium, characterised by the plasticity and artificiality of its subjects (Wells 182), by creating stories that focussed on inorganic objects such as lamps, bicycles and children’s toys, as demonstrated by Luxo Jr. (John Lasseter, 1986), Red’s Dream (John Lasseter, 1987)and Tin Toy (John Lasseter, 1988)respectively. These examples also demonstrate Pixar’s early experimentations into the animation of human characters with realistic attributes, which were later developed into the family that features in Toy Story. The contrasting appearance of the authentic-looking “industrially manufactured forms” (Gurevitch 142) of the toy protagonists and the rudimentary human characters draws attention to the restrictions of the medium.

The significant advancements made in CG human characters are now evident when looking back at twenty years of Pixar short films, from the baby in Tin Toy, to the eponymous protagonists in Geri’s Game and Presto (Doug Sweetland, 2008). Furthermore, the progressive refinement of the character of Andy across fifteen years of the Toy Story trilogy is further evidence of the significance of Pixar’s research and development through these short films, which were fundamental for developing characters and narratives for the studio’s full-length features. The concept for Toy Story clearly derives from Tin Toy, which depicts toys coming to life. Geri’s Game is particularly significant to the progress of digitally animated human characters, including the appearance of skin, hair and clothing. It is therefore no coincidence that Geri appears as the toy repairman in Toy Story 2 (John Lasseter, Ash Brannon and Lee Unkrich, 1999). This initial research laid the foundations for the highly sophisticated human representations in The Incredibles (Brad Bird, 2004) and, more recently, the progress made in computer-generated fabric and human hair seen in Brave.

Figure 1: Human representation in Tin Toy (John Lasseter, 1988). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

Figure 2: Human representation in Geri’s Game (Jan Pinkava, 1998). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

Figure 3: Human representation in Presto (Doug Sweetland, 2008). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2012. Screenshot.

In January 2014 the International 3D and Advanced Imaging Society honoured Pixar Animation Studios with a highly prestigious award for creative excellence. In the past, the studio has received four gold Lumière Awards from the society, more than any other studio ever has (Khatchatourian). The tools and methods developed by Pixar, including the studio-produced RenderMan software, have today become the industry standard for both animated and live-action filmmaking. Developed alongside Pixar’s short film projects, RenderMan is a modelling and rendering programme used to produce photorealistic images and visual effects. The software can be used to create texture mapping and digital camerawork, including lighting sources, motion blur and depth of field, which resemble those of live action cinema. [1] Since the early 1990s every film that has won the Academy Award for best visual effects was rendered using RenderMan, including Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993), King Kong (Peter Jackson, 2005) and Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010). As popular mainstream cinema’s utilisation of computer-generated visual effects grows, the distinction between live action and animation becomes progressively blurred (Debruge). As Chris Pallant has remarked, “photorealistic CGI is now often indistinguishable from conventional live-action imagery” (133). This is also apparent in Pixar’s most recent short film, The Blue Umbrella (Saschka Unseld, 2013), where the photorealism of the visual representation of the landscape and characters makes it difficult to differentiate between animation and live action. This mainstream photorealist aesthetic has been criticised by artists working with more traditional methods. Marjane Satrapi, writer and codirector of the 2D feature Persepolis (Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi, 2007) has argued that “there’s a perfection about computer-generated animation that doesn’t look natural and a coldness … compared to the expressive vibrations of the hand that give life to hand-drawn animation” (Satrapi in Power 117). For her, “traditional animation … like people, has imperfections” (Satrapi).

I argue that Pixar today challenges the photorealist style that characterises CG animation by creating digital images that present a distinctive organic aesthetic. In particular, Enrico Casarosa, director of La Luna, has reintroduced imperfect handmade textures and a muted colour palette by scanning watercolour paintings, which were then applied onto the digital surfaces (“La Luna: Behind the Scenes”). This is a method called texture mapping, a “common technique to make computer-generated imagery more realistic [by applying] a scanned or painted image … to a surface, thus providing fine color detail on an otherwise plain-looking surface” (Apodaca and Gritz 183). As we can see from La Luna,however, the technique can be employed not at the purpose of increasing realism but, at the opposite, to make the image look more stylised.

Differently from the “perfection” of computer-generated images that both Satrapi and Casarosa highlight, Pixar’s experimentation with textures suggests a more expressive aesthetic than has previously been accomplished in digital animation. Although this could be interpreted as a way of increasing realism through the mimicking of real textures, thus moving away from a traditional aesthetic, it is the expressiveness that these textures evoke that, I argue, has facilitated a more organic aesthetic. In WALL-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008), software was used to create a dystopian debris-filled world and a robot protagonist that is rusty, outdated and discoloured, highlighting an idea of “imperfection” sought by Satrapi and Casarosa, which was achieved by hand-drawn methods. Displacement shaders in WALL-E were used to reposition surface details such as “bumps, grooves, general crust and roughness” (Apodaca and Gritz 192), which add another dimension to the detail of each texture. By its nature CG animation creates a distance between animator and animation that is not present in hand-produced methods. The textures exhibited here generate an expressive aesthetic previously unaccomplished by CG animation, and demonstrates a humanistic stance that is played against the impression of a computer-generated, “perfect”, impersonal animation.

La Luna’s organic aesthetic is not a complete departure for Pixar, but a development of the studio’s earlier short films. Red’s Dream, Tin Toy and Knick Knack (John Lasseter, 1989) offer an early indication of the studio’s preference for a more organic look demonstrated by experimentations with textures and patterned surfaces. Early exploration into different textures is already evident in Tin Toy, in which a bird’s-eye view of the protagonist moving across the room shows a glossy magazine, a fabric sofa and wood-grain flooring. The studio continued its experimentation with patterned wallpaper and a more elaborate wood-grain effect in Knick Knack. The level of detail in texture representation that appears ten years later in Geri’s Game is markedly sophisticated in comparison. Naturally, the refinement achieved in La Luna over twenty years later is remarkable, particularly through the depiction of the stars, which have a striking opaque look. The textures in Pixar’s films arguably elicit a haptic experience, which is described by Vivian Sobchack as a “sensuous experience of the movies … able to touch and be touched by the substance and textures of images” (65). Laura Marks has described how cinema may “evoke the sense of touch by appealing to haptic visuality” (162), and has argued that the “haptic image forces the viewer to contemplate the image itself instead of being pulled into the narrative” (163). The tactile images throughout La Luna generate haptic visuality through the appearance of textures, in particular the boat and stars. As Michał Oleszczyk has suggested, “far from the usual golden glitter, the hundreds of stars featured in this movie have a look and feel all their own. Part cookies, part ceramic trinkets, they emit a warm glow that doesn’t seem dangerous in the least—one is tempted to reach out and touch them without fear of burning one’s hand” (Oleszczyk). The organic textures and watercolour backgrounds utilised in La Luna reintroduce the warmth of human imperfection in digital animation, a technique that is in evidence in Pixar’s theatrical releases WALL-E and Up (Pete Docter and Bob Peterson, 2009), for example.

Figure 4: Textures in Tin Toy (John Lasseter, 1988). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

Figure 5: Textures in Knick Knack (John Lasseter, 1989). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. Screenshot.

Figure 6: Textures in La Luna (Enrico Casarosa, 2011). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2012. Screenshot.

In La Luna the tactility of the textures is also emphasised through a process of ageing: the boat is made to look as if it had been passed down through generations, and blemishes and scratches make the stars look as old as the universe. The aesthetic clearly complements the narrative, which is about age-old family traditions and an inherited occupation that appears to adopt long-established customs. Although the father and grandfather argue over the most efficient method to collect the fallen stars from the moon, the process remains the same. The simplicity of the characters’ appearance and of the basic tools that facilitate their astronomic task is juxtaposed with the most advanced technology used to create the film. As Montgomery has identified, this method is also employed in Toy Story 2 during a scene in which the characters watch a 1950s television show: “the sequence employs state of the art digital rendering technologies … to create purposefully flimsy looking 2D wooden cut out animals and sets … to achieve an overall grainy, washed-out aesthetic on an analogue television” (9).

As Montgomery has suggested, Pixar’s feature-length films are concerned with issues of nostalgia from as early as Toy Story. However, we are now witnessing the studio’s application of the most advanced digital animation techniques to create an analogue aesthetic, highlighting the predilection for a more organic look and reinforcing the predominance of the nostalgic trend in contemporary cinema.

…And Back Again: Nostalgia

Pam Cook defines nostalgia as a “state of longing for something that is known to be irretrievable” and playing on one’s desire to “recover what has been lost” (3–4). In the case of Pixar, we can understand Cook’s definition of nostalgia vis-à-vis the displacement of traditional hand-drawn techniques in mainstream animation precipitated by Pixar’s own cutting-edge digital technology. In this light, the studio’s experimentation with an organic aesthetic can be seen as a clear attempt to promote the incorporation of more traditional methods and aesthetic, thus making digital animation marketable to wide-ranging, intergenerational audiences, including to age groups that could be potentially alienated by the perfection of CG animation (Montgomery 12). Furthermore, the decision to draw on themes of nostalgia can be interpreted as a clever marketing strategy that pulls on contemporary trends. A catalyst of postmodernism, the nostalgic trend for the analogue has now been in vogue for over twenty years. The popularity of “vintage” and “retro” is today woven into mainstream culture, with vintage clothing, furniture, and appliances all being highly sought-after items. Vinyl album sales for 2013 were the highest since 1997 (Lachno), and the widespread popularity of apps like Instagram suggests an ever-growing nostalgia trend. In April 2012 Facebook purchased Instagram for $1 billion, “proving that nostalgic capital is worth big money” (Conner). According to Michael Pickering and Emily Keightley, the sociology of nostalgia is useful for “helping cultures to adapt to rapid change” (931), by creating a romanticised view of the past, which is often viewed as regressive and promoting sentimentality. As Svetlana Boym has stated, “the 20th century began with a futuristic utopia and ended with nostalgia. The optimistic belief in the future has become outmoded while nostalgia, for better or for worse, never went out of fashion, remaining uncannily contemporary” (Boym). Today’s media extensively exploit this affection for the past to market consumer products and commodities (Cook 4–5). In 2013, a report in Adweek singled out seven brands that used nostalgia as a marketing tool and “shot to the top of its Brand Power Index (BPI)”, demonstrating that brands “connecting to the past resonated strongly with consumers” (“Seven Brands”). [2] Brands such as Jack Daniel’s, Lego and Microsoft Windows increased its BPI between 18–27% as a result of nostalgic marketing strategies (“Seven Brands”).

As consumer products, movies can be analysed in the same way. Making reference to a notable “convergence between the aesthetics of the animated feature and the aesthetics of the advertising industry” (Gurevitch 141–2), Leon Gurevitch has highlighted Justin Wyatt’s argument that, in the 1990s, “the polished, reflective, high definition look of high concept films” was characteristic of a “general advertising aesthetic of the time” (142). In his argument Gurevitch singles out the example of the industrial aesthetic present in Pixar’s Toy Story and Cars (John Lasseter and Joe Ranft, 2006). The emergence of a “nostalgic” or “vintage” look similar to the one that characterises the contemporary advertising aesthetic is reflected in animated film. Beyond the Pixar case, nostalgic elements also feature both thematically and aesthetically in Disney’s animated feature film canon. Most recent examples are Disney’s 2D theatrical release, The Princess and the Frog (Ron Clements and John Musker, 2009) and the retro-themed Wreck-it Ralph (Rich Moore, 2012). In addition, nostalgia is a marketing strategy used extensively by Disney; one example highlighted by Montgomery is Disney’s “Year of a Million Dreams” campaign, which “restages iconic scenes from Disney features using popular actors and celebrities” (12). Further examples from other animation studios are DreamWorks Animation’s Shrek Forever After (Mike Mitchell, 2010), which depicts the protagonist’s longing for the past, and Kung Fu Panda (Mark Osborne and John Stevenson, 2008), where the opening hand-drawn dream sequence evokes nostalgia for traditional Chinese shadow puppetry (Power 124).

Since the release of Toy Story, Pixar’s feature-length animations have portrayed affection for the past as a common theme, often demonstrating a “pronounced nostalgia for obsolete or outmoded technologies” (Montgomery 8). This is particularly evident in the Toy Story franchise, which evokes sentimentality for childhood during a time when digital technologies were uncommon among children. Andy, the child protagonist of Toy Story and Toy Story 2,plays with basic toys many of which are familiar to an adult audience, including dolls, dinosaurs, Mr Potato Head, Slinky Dog, Etch-a-Sketch and miniature soldiers. In fact, the most advanced toy Andy owns besides Buzz Lightyear is a battery-operated remote-controlled car. Over ten years later Toy Story 3 (Lee Unkrich, 2010) features these same toys, which are now outdated and unappreciated. Molly, Andy’s younger sister, is more interested in her mobile phone, MP3 player and laptop, although she is now the same age as Andy when he appeared in the earlier Toy Story films (Montgomery 9). In addition, the first two films feature traditional modes of consumerism; Al’s Toy Barn, the fictional franchise toyshop, is particularly prominent in Toy Story 2. Only recently has the studio entertained the concept of online purchasing and contemporary auction websites, demonstrated by Pixar’s television short Toy Story of Terror (Angus MacLane, 2013), which incidentally explicitly underlines the series’ nostalgia towards the increasingly antiquated toy protagonists. Themes of nostalgia are also prominent in The Incredibles, Cars, WALL-E, and Up. These films depict a romanticised view of the past, a longing for a lost period in time and a yearning for departed love. They also favour prior technology from the analogue age, as made explicit in WALL-E, where the protagonist is presented as a more sympathetic character than EVE with her cold demeanour and sleek, hyper-modern appearance. As the growing success of CG animation continues to replace hand-drawn traditions in mainstream cinema, themes of nostalgia help to allay any “possible sense of digital alienation” (Schaffer 88).

As previously noted, while being connected to prior trends La Luna marks a pivotal shift within Pixar’s canon of short films. Not only does the film evoke nostalgia thematically, with reference to childhood and family traditions, but its organic aesthetic also reflects nostalgia for traditional hand-drawn animation. The same nostalgia is also evident in Disney’s short films Paperman and Get a Horse!.Arguably, both films are influenced by Pixar’s cutting-edge approach to encourage nostalgic sensibilities for Disney’s classic animation, demonstrating an interesting blend of old and new, which forms the basis of later discussions on the integration of 2D and CG techniques. The monochrome aesthetic employed in both Paperman and Get a Horse! connects viewers to an idealised past. In particular, the visual aesthetic in the latter evokes sentiment towards Disney’s past, by replicating the look of a classic 1920s black-and-white Mickey Mouse cartoon. The film, which incorporates archive sound of Walt Disney as the voice of Mickey, is a throwback to Disney’s animation heritage. To achieve an effect of authenticity animators added deliberate imperfections and mistakes, which included film damage, light flickers, camera shakes and frames where Mickey’s tail is missing or where Minnie’s feet are not registered to the ground. The past and present are differentiated by opposites: monochrome past and colourful present, the horse and cart versus the car, and Mickey as the protagonist against Peg-Leg Pete as the antagonist. The final victory for Mickey and his friends as they return to the past is Pete’s “imprisonment” in the present day, once again suggesting a championing of the analogue. In order to understand how Pixar, and in particular John Lasseter, has influenced these recent Disney films, it is necessary to briefly contextualise the Disney-Pixar relationship.

…And Beyond: 2D Meets CG

In 2006, the Walt Disney Company acquired Pixar Animation Studios for $7.4 billion and appointed Lasseter as chief creative officer for both Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios. In a recent Variety article Disney’s current chairman and chief executive officer Robert Iger is quoted stating that the “strong performance of Frozen and Tangled before that, is in part the result of purchasing Pixar” (Graser). According to Iger, when the company bought the studio the “goal was to rejuvenate Disney Animation under new leadership” (Graser). After his appointment as creative officer at Disney, Lasseter supervised production on The Princess and the Frog, Disney’s first fully 2D animated film in five years, following the commercially disappointing Home on the Range (Will Finn and John Sanford, 2004). According to Pallant, without Lasseter this “return to a more traditional style of animation may never have happened” (142). His implementation at Disney of a shorts programme similar to the one at Pixar to revive animators’ creativity has proven invaluable for the application of 2D techniques within Disney’s CG animation. This process has allowed Disney to maintain a “link to its past, both stylistically and thematically” (Telotte 162). Furthermore, Disney’s films increasingly “demonstrate the relationship between the organic and the machine” (Wells 23), which is further enhanced by the blending of 2D and CG elements.

The integration of 2D and CG animation is by no means revolutionary. The technique has been experimented with since the early days of digital animation, though much of this experimentation was driven by the limitations presented by CG animation or by the lower costs of cel animation. Inspired by the technology and the effects employed in TRON (Steven Lisberger, 1982), Lasseter, then an animator at Disney, worked on a test based on Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. The 30-second short featured “hand-drawn characters moving around a three-dimensional set” (Paik 39). Lasseter planned to employ the same technique for a feature-length film based on Thomas Disch’s novel The Brave Little Toaster, but it was considered too expensive. The film was later picked up by Hyperion Pictures and had a limited theatrical release in 1987. By that time Lasseter had produced three short CG animated films under the Pixar banner and submitted a paper to the 1987 SIGGRAPH (Special Interest Group on Graphics and Interactive Techniques) Conference titled “Principles of Traditional Animation Applied to 3D Computer Animation”. According to Lasseter, “the application of some of these principles [including squash and stretch, timing, anticipation, etc.] mean the same regardless of the medium of animation” (Paik 61). Pixar’s earlier shorts The Adventures of André and Wally B. (John Lasseter, 1984) and Red’s Dream both feature hand-drawn elements within a predominantly digital environment.

In the late 1980s the Pixar Image Computer (PIC) and the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) package were bought by Disney to convert the studio’s ink and paint process from 2D to digital, which “gave artists a much broader and more finely varied palette than traditional methods” (Paik 57). This technique was successfully trialled for the final scene of The Little Mermaid (Ron Clements and Jon Musker, 1989) and implemented in full on The Rescuers Down Under (Hendel Butoy and Mike Gabriel, 1990). CAPS was primarily a camera system capable of recreating a live-action camera, never before possible for cel animation (Paik 57). The ballroom scene from Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991) is one of the better-known examples of its use, coming from one of the first animated feature films to utilise this technique. The sequence combines hand-drawn characters and a CGI background, which enabled animators to effortlessly manipulate the 3D space, altering depth, colour and shading. The process was also implemented in Mulan (Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook, 1998) during the mountain battle scene between the Chinese and the Hun armies. We are now witnessing the pinnacle of digital animation, where the desired aesthetic can be achieved with little to no restrictions. As previously discussed, Pixar saw the early limitations of CG animation as a virtue, by creating stories that appealed to the medium. The recent emergence of a more organic aesthetic and the implementation of 2D techniques enhance the more experimental narratives Pixar for which has become known and highlights the progress made in computer-generated animation. La Luna is exemplary within the studio’s short film canon, as the painterly approach to the aesthetic serves to enhance the narrative, demonstrating the versatile nature of contemporary digital animation to accomplish a desired effect.

Similarly, Disney’s Paperman employs hand-drawn methods to reiterate the penchant for a more traditional look. The film, which was released theatrically with Wreck-it-Ralph, is set in 1940s Manhattan and is about the chance meeting between two people on a railway platform. As with Get a Horse! the film evokes a fondness and nostalgia for old movies. However, in this case attention should be drawn to the techniques used throughout the film to create a hybrid of 2D and CG that had not been previously explored. The film blends old and new animation styles, teaming the expressiveness of the animator’s line with the stability and refinement of computer animation. The process was born out of the director’s desire to somehow include the film’s initial concept drawings. The end result is a more expressive aesthetic and a more subtle way of integrating 2D and CG. It is pertinent to note that the technique was developed in-house by a small team at Walt Disney Animation Studios. The programme, named Meander, “is a hybrid vector/raster-based drawing and animation system that gives artists an interactive way to craft the film” (Failes). This aesthetic approach acknowledges the studio’s past while simultaneously pointing at the future for Disney animation. There are direct parallels between La Luna and Paperman, namely the application of hand-drawn and organic techniques within a digitally animated environment, to create an aesthetic that evokes nostalgia for traditional animation. Furthermore, the techniques employed by each studio respectively respond to their own histories. In La Luna, Pixar applies organic texture mapping to evoke nostalgia while prioritising digital animation, whereas Paperman demonstrates Disney’s application of a hand-drawn style to evoke nostalgia, while favouring 2D animation.

Pixar’s influence on Disney’s animation aesthetic and the development of new techniques has been invaluable to the regeneration of Disney’s feature animation. Under the influence of Lasseter, it is “arguably only Disney that is now able to produce a 2D animated feature capable of successfully competing in the market” (Pallant 142). Since the release of La Luna,Pixar’s Research Group has been experimenting with different methods of integrating hand-drawn art within digital animation, developing a process to create stylised animation (see Benard et al). As research continues, these techniques that were successfully brought to fruition in La Luna will begin to be applied to Disney-Pixar’s mainstream feature-length aesthetic.

Figure 7: 2D/CG Hybrid in Paperman (John Kahrs, 2012). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2013. Screenshot.

The blending of 2D and CG techniques is also used to comment on the relationship between hand-drawn and digital animation. Pixar’s demonstration of the two techniques in the short film Day & Night, released theatrically with Toy Story 3,suggests 2D is a window into CG by displaying how “these two styles of animation can be successfully combined” (Pallant 146). As the two hand-drawn figures with see-through bodies move across the screen, the landscape seen through them, which depicts contrasting day and night scenes (in the same landscape we see bees in a meadow during the day and crickets chirping at night, for example), is illustrated using digital animation. The film realises Joe Letteri’s statement that “computer animation is a natural extension of hand-drawn methods” (214). The integration of 2D and CG methods can be interpreted as an allegory of the emergence of digital animation and the consequent displacement of hand-drawn traditions. This is particularly evident in Day & Night and Get a Horse!.Pixar amicably depicts the relationship between the two styles in the former, while Disney explicitly favours 2D over CG in the latter. At the beginning of Day & Night Pixar underlines the differences between the eponymous figures, while simultaneously drawing attention to the contrasts between hand-drawn and digital animation. As the two figures finally come together in the narrative, the two-dimensional characters simultaneously integrate with the three-dimensional environments, evoking nostalgia for the early exploration of hand-drawn characters within digital environments, an approach attempted by Lasseter almost twenty-five years earlier with Where the Wild Things Are and The Brave Little Toaster. In contrast, Get a Horse! continuously draws attention to the differences between traditional and digital animation. In fact, the two techniques are separated throughout the film by a cinema screen. The brash statement at the start of the film, “Make way for the future!”, represented here by the antagonist, Peg-Leg Pete, suggests how digital works superseded traditional animation. The final retort, “Get a horse!”, represented by the protagonists (Mickey Mouse and friends) indicates nostalgia and a preference for Disney’s traditional 2D animation. In addition, Pete is banished to the modern day as punishment, appearing as a CG characterisation, while Mickey and his friends return to the “safety” of the past and emerge as two-dimensional characters. The final affirmation of progress as “bad” and the past as “good” in the film resonates with the idea of nostalgia as a safe haven, but also as a regressive state.

Conclusion

Pixar Animation Studios is continuously at the forefront of cutting-edge computer animation, originating from the company’s desire to push the boundaries of digital animation demonstrated by the research and development process of the studio’s short films. Moreover, the technology developed by the studio has set the industry standard for digital animation in animated and live action cinema. The popularisation of Pixar’s CG aesthetic that followed the success of Toy Story, led many animation studios including DreamWorks and Disney to dissolve production on 2D animated works to focus on a digital output. We are now witnessing the pinnacle of CG animation and its photorealist aesthetic that is often indistinguishable from live action. Pixar’s return to a more organic aesthetic, which champions the analogue and evokes nostalgia, is characteristic of contemporary trends in media, marketing and animation more widely. Thematically, Pixar films demonstrate a fondness and affection for the past, which is echoed in a number of features by the studio. This approach has in turn influenced Disney’s digital output over the last few years, including Tangled (Nathan Greno and Byron Howard, 2010), Wreck-it-Ralph, and Frozen (Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, 2013)—all of which credit John Lasseter as executive producer. Pixar’s experimentation with an organic aesthetic and textures has led back to a more traditional process in animation, with the studio’s cutting-edge approach now emerging from the blending of 2D and CG techniques. Most exciting is that we are now witnessing the first examples of the blending of old and new methods as an artistic and aesthetic choice.

Although the Walt Disney Company acquired Pixar in 2006, we are only now beginning to witness the effect of that partnership on each studio. The effect Walt Disney Animation has had on the work of Lasseter as an animator has led back to a more organic aesthetic within Pixar’s digital animation. Similarly, Pixar’s CG aesthetic and the development of the blending of old and new techniques has enabled a triumphant return of Walt Disney Feature Animation, not just in terms of style but also narratively. Furthermore, the nostalgia of Pixar’s animators and directors for Disney animation has facilitated a return to traditional animation methods. The short films analysed throughout this article demonstrate the “flexible nature of a digital environment” (Power 124) to achieve a desired aesthetic, by embracing different styles and techniques. The more expressive aesthetic outlined here act to enhance the narrative, rather than just to showcase the latest advancements in technology. This process, which spans over thirty years, marks the pinnacle of CG animation led by the pioneers of digital animation.

Notes

[1] For a more thorough account of the capabilities of RenderMan see the Pixar website (renderman.pixar.com/view/renderman); and Apodaca and Gritz.

[2] According to Adweek “every quarter, the BPI ranks the most talked about brands as determined by factors like social media buzz and online searches, comparing their scores to the previous three months” (“Seven Brands”).

References

1. The Adventures of André and Wally B. Dir. John Lasseter. Pixar Animation Studios, 1984. Film.

2. Apodaca, Anthony A., and Larry Gritz. Advanced RenderMan: Creating CGI for Motion Pictures. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann, 2000. Print.

3. Beauty and the Beast. Dir. Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1991. Film.

4. Benard, Pierre, Aaron Hertzmann, and Michael Kass. “Computing Smooth Surface Contours with Accurate Topology”. Pixar Research Group. Web. March 2014. <http://graphics.pixar.com/library/>.

5. The Blue Umbrella. Dir. Saschka Unseld. Pixar Animation Studios, 2013. Film.

6. Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001. Print.

7. ---. “Nostalgia.” Atlas of Transformation. Web. 12 Aug 2014. <http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/n/nostalgia/nostalgia-svetlana-boym.html>.

8. Brave. Dir. Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman. Pixar Animation Studios, 2012. Film.

9. A Bug’s Life. Dir. John Lasseter and Andrew Stanton. Pixar Animation Studios, 1998. Film.

10. Cars. Dir. John Lasseter and Joe Ranft. Pixar Animation Studios, 2006. Film.

11. Conner, Cheryl. “Star Wars, Elvis, Miller Lite: How Marketers Use ‘Nostalgic Capital’ to Cash in on the Past.” Forbes. Web. 20 Jan 2014. <http://www.forbes.com/sites/cherylsnappconner/2014/01/20/star-wars-elvis-miller-lite-how-savvy-marketers-use-nostalgic-capital-to-cash-in-on-the-past/>.

12. Cook, Pam. Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema. Oxon: Routledge, 2005. Print.

13. Day & Night. Dir. Teddy Newton. Pixar Animation Studios, 2010. Film.

14. Debruge, Peter. “Oscars: With Films Like Gravity, Where Does Animation Branch Draw the Line?” Variety. Web. 7 Nov 2013. <http://variety.com/2013/biz/awards/eye-on-the-oscars-with-films-like-gravity-where-does-toon-branch-draw-the-line-1200806697/>.

15. Disch, Thomas M. The Brave Little Toaster. London: Doubleday Books, 1986. Print.

16. Failes, Ian. “The Inside Story Behind Disney’s Paperman.” Fxguide. Web. 31 Jan 2013. <http://www.fxguide.com/featured/the-inside-story-behind-disneys-paperman/>.

17. Frozen. Dir. Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2013. Film.

18. Geri’s Game. Dir. Jan Pinkava. 1998. Pixar Short Films Collection, Volume 1. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

19. Get a Horse! Dir. Lauren MacMullan. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2013. Film.

20. Graser, Marc. “Disney’s ‘Frozen’ Plans: Theme Parks, Broadway, Videogames and Beyond.” Variety. Web. 5 Feb 2014. <http://variety.com/2014/biz/news/disneys-frozen-plans-theme-parks-broadway-videogames-and-beyond-1201088544/>.

21. Gurevitch, Leon. “Computer Generated Animation as Product Design Engineered Culture, or Buzz Lightyear to the Sale Floor, to the Checkout and Beyond!” Animation 7.2 (2012): 131–49. Print.

22. Home on the Range. Dir. Will Finn and John Sanford. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2004. Film.

23. Inception. Dir. Christopher Nolan. Warner Bros., 2010. Film.

24. The Incredibles. Dir. Brad Bird. Pixar Animation Studios, 2004. Film.

25. Jurassic Park. Dir. Steven Spielberg. Universal Pictures, 1993. Film.

26. Khatchatourian, Maane. “Pixar Animation to be Honored by 3D & Advanced Imaging Society.” Variety. Web. 19 Nov 2013. <http://variety.com/2013/film/news/pixar-animation-to-be-honored-by-3d-advanced-imaging-society-1200855389/>.

27. King Kong. Dir. Peter Jackson. Universal Pictures, 2005. Film.

28. Knick Knack. Dir. John Lasseter. 1989. Pixar Short Films Collection, Volume 1. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

29. Kung Fu Panda. Dir. Mark Osborne and John Stevenson. DreamWorks Animation Studios, 2008. Film.

30. La Luna. Dir. Enrico Casarosa. 2011. Pixar Short Films Collection, Volume 2. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2012. DVD.

31. “La Luna: Behind the Scenes.” Pixar. Web. 12 Sep 2014. <www.pixar.com/short_films/Theatrical-Shorts/La-Luna>.

32. Lachno, James. “Vinyl Sales Highest for 15 Years.” The Telegraph. Web. 7 Jan 2014. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/music-news/10556186/Vinyl-sales-highest-for-15-years.html>.

33. Letteri, Joe. “Digital Heroes and Computer-Generated Worlds.” Nature 504 (2013): 214–16. Print.

34. The Little Mermaid. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1989. Film.

35. Luxo Jr. Dir. John Lasseter. Pixar Animation Studios, 1986. Film.

36. Marks, Laura U. The Skin of Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Durham: Duke U.P., 2000. Print.

37. Montgomery, Colleen. “Woody’s Roundup and Wall-E’s Wunderkammer: Technophilia and Nostalgia in Pixar Animation.” Animation Studies Online Journal. Web. 2 Sept 2011. <http://journal.animationstudies.org/colleen-montgomery-woodys-roundup-and-walles-wunderkammer/>.

38. Mulan. Dir. Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1998. Film.

39. Oleszczyk, Michał. “Pixar’s Moonrakers.” RogerEbert.com. Web. 12 Dec 2012. <http://www.rogerebert.com/far-flung-correspondents/pixars-moonrakers>.

40. Paik, Karen. To Infinity and Beyond! The Story of Pixar Animation Studios. London: Virgin Books Ltd., 2007. Print.

41. Pallant, Chris. Demystifying Disney: A History of Disney Feature Animation. London: Continuum, 2011. Print.

42. Paperman. Dir. John Kahrs. 2012. Wreck-it Ralph. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2013. DVD.

43. Pixar: 25 Magic Moments. Dir. Richard Mills. BBC Three, 2011. Film.

44. Persepolis. Dir. Vincent Paronnaud and Marjane Satrapi. 2.4.7. Films, 2007. Film.

45. Pickering, Michael, and Emily Keightley. “The Modalities of Nostalgia.” Current Sociology 54.6 (2006): 919–41. Print.

46. Power, Pat. “Animated Expressions: Expressive Style in 3D Computer Graphic Narrative Animation.” Animation 4.2 (2009): 107–29. Print.

47. Presto. Dir. Doug Sweetland. 2008. Pixar Short Films Collection, Volume 2. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2012. DVD.

48. The Princess and the Frog. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2009. Film.

49. Red’s Dream. Dir. John Lasseter. Pixar Animation Studios, 1987. Film.

50. The Rescuers Down Under. Dir. Hendel Butoy and Mike Gabriel. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1990. Film.

51. Satrapi, Marjane. “Persepolis: Production Process.” Film Education. Web. 12 Sep 2014. <http://www.filmeducation.org/persepolis/production-process.html>. Quoted in Pat Power, “Animated Expressions: Expressive Style in 3D Computer Graphic Narrative Animation”. Animation 4.2 (2009). 117. Print.

52. Schaffer, William. “The Importance of Being Plastic: The Feel of Pixar.” Animation Journal 12 (2004): 72–95. Print.

53. Sendak, Maurice. Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper and Row, 1963. Print.

54. “Seven Brands that are Winning with Nostalgia: Living in the Past isn’t Such a Bad Thing.” Adweek. Web. 5 May 2013. <http://www.adweek.com/news/advertising-branding/seven-brands-are-winning-nostalgia-149174?page=2>.

55. Shrek Forever After. Dir. Mike Mitchell. DreamWorks Animation Studios, 2010. Film.

56. Sobchack, Vivian. Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: U. of California P., 2004. Print.

57. Tangled. Dir. Nathan Greno and Byron Howard. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2010. Film.

58. Telotte, J.P. The Mouse Machine: Disney and Technology. Urbana and Chicago: U. of Illinois P., 2008. Print.

59. Tin Toy. Dir. John Lasseter. 1988. Pixar Short Films Collection, Volume 1. Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

60. Toy Story. Dir. John Lasseter. Pixar Animation Studios, 1995. Film.

61. Toy Story 2. Dir. John Lasseter, Ash Brannon and Lee Unkrich. Pixar Animation Studios, 1999. Film.

62. Toy Story 3. Dir. Lee Unkrich. Pixar Animation Studios, 2010. Film.

63. Toy Story of Terror. Dir. Angus MacLane. Pixar Animation Studios, 2013. Film.

64. TRON. Dir. Steven Lisberger. Walt Disney Productions, 1982. Film.

65. Up. Dir. Pete Docter and Bob Peterson. Pixar Animation Studios, 2009. Film.

66. WALL-E. Dir. Andrew Stanton. Pixar Animation Studios, 2008. Film.

67. Wells, Paul. Understanding Animation. Oxon: Routledge, 1998. Print.

68. Wreck-it-Ralph. Dir. Rich Moore. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 2012. Film.

69. Wyatt, Justin. High Concept: Movies and Marketing in Hollywood. Austin: U. of Texas P., 2003. Print.

Suggested Citation

Haswell, H. (2014) 'To infinity and back again: hand-drawn aesthetic and affection for the past in Pixar's pioneering animation', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, pp. 24–40. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.8.02.

Helen Haswell is a PhD candidate in Film Studies at Queen’s University Belfast. Her research focuses on the brand identity of Pixar Animation Studios following the studio’s acquisition by The Walt Disney Company. Her research interests include the development of CG animation technology, film marketing and distribution.