Shaming Australia: Cinematic Responsesto the “Pacific Solution”

Stephanie Hemelryk Donald

How might it be possible for audiovisual productions across a variety of media platforms to render the experiences of refugees and forced migrants, and particularly their subjection to state-sponsored abuse, in ways that are both ethically defensible and aesthetically compelling? The question was prompted, for me, by viewing a number of works provoked by the Australian government’s political responses to the “refugee crisis” since the “Tampa affair” in 2001—the occasion when Prime Minister John Howard refused to allow the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa to enter Australian waters, because it was carrying 433 refugees rescued from a precarious fishing vessel that had run into trouble. In thinking through the issue, my main critical focus is on Eva Orner’s documentary film about the detention of asylum seekers on the Pacific island of Nauru, Chasing Asylum (2016), the making of which Orner has chronicled in an eponymous book subtitled A Filmmaker’s Story. As well as situating Orner’s film in the context of earlier Australian films about refugees and detainees, I contrast its approach with that of Dennis Del Favero’s short installation piece, Tampa 2001 (2015), which offers a nonrepresentational alternative to the conventional documentary strategies of Chasing Asylum. All the works discussed reveal how inextricably, if often counterintuitively, the two dimensions of aesthetics and ethics are intertwined.

My emphasis in this article is not on the traumatic nature and consequences of the events that all too often befall asylum seekers. Rather, I am concerned with two things. One is the relationship between representational strategies and the reality of those traumatic events. This topic is often framed, at least in the literature on documentary film, in terms of “indexicality”. This concept, derived from the semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce, refers to the fact that, although it bears the trace of the reality it represents (through the mechanical or digital capture of light), a photographic image cannot in itself reveal the nature of that reality, or guarantee the truthfulness of the representation (Cowie 30). Put simply, my first question is about the truth claims implicit in Orner’s film and Del Favero’s installation: given the limits of photographic indexicality, what “reality” can they claim to reveal or create? My second question concerns the implicit ethical contract between artist and audience: not so much truth claims, as the claims a work makes on its audience. This is the concern that lies behind many of today’s discussions about “testimony” and “affect” (see, for example, Richardson; Gregg and Seigworth). Here again, my focus is slightly different. I am interested in the ways in which spectators and audiences are invited to respond to images and sounds that attempt to communicate complex and traumatic refugee stories of dispossession or disappearance. This change of angle allows a move beyond the simple, and sometimes simplistic, notion of “refugee voice”. Instead, it opens up the possibility of a more considered set of expectations about aesthetic judgements, and about art as a political practice of humility and revelatory not-knowing.

Resettlement and Refusal

In 2001, in the wake of the Tampa affair, the Australian government introduced its so-called “Pacific Solution” to the arrival of asylum seekers by boat on the coast of Australia. The policy had three components. First, thousands of islands (most significantly, Christmas Island) were excised from Australian territory, thus preventing anyone landing on them from claiming asylum. Second, the Australian Defence Force was authorised to intercept boats carrying asylum seekers on the high seas. And third, increasingly asylum seekers have been removed to remote detention camps (or “Regional Processing Centres”) in the impoverished Pacific nations of Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island), while their claims to refugee status are assessed. It was in this politically charged moment that a number of Australian documentaries appeared that deal with issues around asylum and migration. The first, in 2002, was Mark Henderson and Christine McAuliffe’s Tampa and Beyond, which collated footage and reportage to create a valuable journalistic document of record that challenged official obfuscations of the incident (Perera). Clara Law’s Letters to Ali (2004) and Tom Zubrycki’s Molly and Mobarak (2003) are more nuanced works that address the capacity for individual morality in the face of contemporary racism, by focusing on the way that a settled Australian family offers hospitality and friendship to a refugee or asylum seeker.

Clara Law migrated to Australia in 1994 from Hong Kong, where she was already an established director. That experience informed her first Australian feature, Floating Life (1996), which explored in fictional form the alienation of arrival and the challenges of resettlement. Letters to Ali was her first digital documentary. It was inspired by a newspaper article about a family that tried to help an Afghani minor, Ali, who had been detained in the remote Port Hedland detention centre in Western Australia. The woman of the family, Trish Kerbi, wrote him letters, arranged legal support, and then, with her husband and four children, drove 3,000 kilometres to visit him. Like many Australians, the family are descended from migrants. Trish’s mother was English and, although her repugnance at the idea of children in detention reflects a sense of maternal, compassionate duty, her reaction is also—as Law’s film makes clear—informed by the lack of tenderness she remembers from her own childhood. As the son of Holocaust survivors, her husband too feels a profound and personal empathy with refugees. As well as following the family’s drama, Law herself features as a major protagonist. As a result, Letters to Ali is also a film about the process of its own making, and about Law’s discovery of previously unknown aspects of Australia as she accompanies the family on their second drive to Port Hedland. Through such strategies, Belinda Smaill has argued, Asian-Australian filmmakers like Clara Law are able to reveal underlying instabilities in mainstream Australian identities that otherwise pass as settled. Moving beyond “established theories of diasporic identity construction and politics”, Smaill shows how they “act as a locus for the circulation of particular emotions in the context of an Australian cultural imaginary” (24; emphasis added)—a phrase that captures something central to many of the works discussed here. Smaill’s evocation of “an Australian cultural imaginary” suggests the nature and extent of the understanding and empathy that the films explore and, in some cases, embody.

In Molly and Mobarak, Tom Zubrycki, a documentary maker whose output spans four decades, establishes the Australian cultural imaginary through the figures of Molly and Lyn, a daughter and mother in the rural town of Young, and then explores the particular emotions generated by their friendship with a fifteen-year-old refugee. Mobarak Tahiri is a Hazara from Afghanistan, as were most of the people rescued by the Tampa. In the early 2000s, he is working in the town’s abattoir on a Temporary Protection Visa. Whereas Lyn’s relationship to Mobarak is above all maternal, for Molly, he is a peer, and she becomes an object of amorous longing for him. Much of the film is taken up with tracing how Mobarak’s feelings for her shape his experience of Australia, and with observing Molly herself, at the same time as the film records Lyn’s attempts to protect the young couple by managing the relationship. Molly and Mobarak has been read by Kate Nash as an example of how the power relation between filmmaker (here, Zubrycki) and subject (Lyn Rule) can be complicated by shared values, knowingness on the part of the subject, and the relationship of trust that both parties must cultivate to produce a meaningful outcome (“Exploring”; “Stealing”). Lyn is very openly in the room “with” Zubrycki, even though the director never appears on camera (Nash, “Exploring” 25–30). Lyn makes an impressive bid for on-screen control, which requires Zubryzcki to situate himself as an agent in the film’s effects. However, neither Nash nor Zubrycki explicitly addresses the question of what the very vulnerable Mobarak felt about his involvement and treatment in the filmmaking process, other than to provide an assurance that he consented to the film being made and approved it after completion. Although the detainee and the refugee appear in their titles, it is the nature of the filmmaker’s presencethat links Letters to Ali and Molly and Mobarak to Eva Orner’s role in Chasing Asylum, and so raises the question of the ethical significance of that authorial presence, even more than its narrative functions.

In the years between those immediately post-Tampa films and Chasing Asylum, Australian governments led by both major parties bore down on boat arrivals’ rights to refugee status, most brutally through their transportation offshore for “punitive detention in jail-like establishments” pending their processing, resettlement, or refoulement to their countries of origin (van Berlo 36). Facilities on Nauru and Manus were notoriously inadequate from the start. As early as 2005, Michael Gordon, the first journalist to be given unrestricted access to the Nauru camp, observed their degrading effects. He learned about one nine-year-old, who had been ill for ten days after his family’s latest rejection, from a family member:

When his father took him to the doctor, he said, “Your son is very lonely. There is no treatment.” The older daughter, Ilham, aged fourteen, was the only teenage girl in a camp overwhelmingly comprised of young men. She had to go everywhere with her parents and said she was very depressed and lonely. “It’s very hard for me. I cannot go outside. I cannot go to the dining room. I cannot go shopping or swimming. I [only] go with my family.” (Gordon, “Six”; emphasis added)[1]In 2006, the camps temporarily fell into disuse, only to be reactivated as the flow of migrants increased from 2008 onwards as global geopolitics turned ever uglier. Australian political leaders have sought to justify the intensifying severity of each new iteration of the Pacific Solution (which was handed over to the military and renamed “Operation Sovereign Borders” in 2013) by asserting that its primary purpose was to prevent the loss of life as asylum seekers made the dangerous crossing from Indonesia in unseaworthy vessels. Such retrospective claims about the supposed “success” of the policy have been vigorously contested by legal scholars, not least the former Chair of Australia’s Human Rights Commission, Gillian Triggs (Triggs et al.; van Berlo 34–36). These critics have found that the camps offer little security, minimal privacy and no scope for self-reliance, with scant opportunities for employment or productive activity. Men, women and children alike suffer from the debilitating uncertainty, pervasive hopelessness and endemic deterioration in mental health that are the all-too-predictable consequences of imprisonment without charge and without end-date (Triggs et al. 19–25). In a series of articles for The Guardian,the Kurdish writer, and Manus Island detainee, Behrouz Boochani has chronicled a series of suicides in his camp as chilling evidence of the harm knowingly being done by Australian policy (Boochani; Boochani et al.).[2] In 2014, Jane McAdam and Fiona Chong charted in detail the many occasions on which Australia’s refugee policy has contravened treaties by which it is bound, as well as its general human rights obligations. In addition to showing how perfectly legal asylum seekers and refugees have been criminalised through offshore processing, McAdam and Chong highlight the plight of child migrants and the way that Australia has repeatedly breached the provisions of the Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to both of which it is a signatory.

This is the state of affairs that Eva Orner set out to expose in Chasing Asylum, with the explicit aim of making “a film that would shame Australia” (Orner qtd. in Dunks). It is an unapologetically activist film, not only in its content, but also in the way that it was produced, exhibited and received. Orner funded it entirely by coaxing contributions from private donors, with no state subsidies. Much of her photographic evidence was shot covertly by young Australians working in the camps. This exposed them to considerable risk. In 2015, midway through production of the film, the Australian government brought into being a new entity: the Australian Border Force (ABF). As well as mandating drug and alcohol screening tests and steps for “the management of serious misconduct”, the Act enabling the creation of the ABF put in place “secrecy and disclosure provisions”, backed up by the threat of two years imprisonment, that were designed to deter whistle-blowing by medical, social services and security personnel in the camps (Australian Border Force Act 35–42).

Once complete, Chasing Asylum was distributed largely through subscription screenings, usually followed by discussions, as well as being shown in festivals and on television.[3] The film won the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts award for best feature-length documentary in 2016 and it was nominated for awards by the Australian Film Critics Association and the London Film Festival. Press reviews mostly talked about its effectiveness as a polemic, often emphasising the outrage and compassion evoked by the grim reality it revealed. The Sydney Morning Herald described it as “the most thorough exposé yet of the so-called Pacific Solution” (Wilson) and Variety as “a powerfully crafted plea for human rights [that] will move many viewers to tears” (Kuipers). The Guardian’s reviewer experienced it as “one of the most important, distressing and necessarily relentless documentaries I have seen this year” (Ramaswamy).

Given that history, why do my questions about indexicality and audience engagement prompt qualms about Chasing Asylum? In part, these misgivings involve what Bill Nichols conceptualises as the “voice” of documentary film. By this, he means “something narrower than style”. Voicein documentary is “that which conveys to us a sense of a text’s social point of view, of how it is speaking to us and how it is organizing the materials it is presenting to us” (50). Far from being restricted to “any one code or feature, such as dialogue or spoken commentary”, voice refers to the “pattern formed by the unique interaction of all a film’s codes” (18–19). Thus, one might observe that the distinctive “voice” of both Letters to Ali and Molly and Mobarak is determined to a significant degree by the presence—explicitly in the former, implicitly in the latter—of the filmmaker, and the way that the relationship of inquisitive trust established between filmmaker and the family being documented plays a large part in determining the meaning and emotional impact of the film. In highlighting that the “reality” of their films is constructed through the recorded drama of that interaction, and that film can never show reality raw on screen, Law and Zubrycki are acknowledging the limits of indexicality. The photograph (or film) “signals an event”, explains Elizabeth Cowie; “it is a sign of contingent and ongoing reality from which it has been cut out and cut off spatially and temporally” (31). Hence the limitations of its possible truth claims: “That it also bears the imprint of that reality does not engender meaning any more than looking at reality”. Films cannot provide “a direct full access to either contemporary or historical reality, for a process of signification that is also a mediation is necessarily introduced in the temporal transpositions its recording produces”. What photograph and film do produce is evidence, which can then be mobilised “by a discourse of law, of ethics, or of psychology in order to bring the image to speak its ‘truth’”. It is through this act of narrative mobilisation that the document is transformed into the documentary: “a presentation of the facts and the testimony of participants in the events and actions shown”.

In similar vein, Nichols underscores the constructed nature of documentary truth. The film’s overall voice arises from the orchestration of its component parts:

(1) the recruited voices, the recruited sounds and images; (2) the textual “voice” spoken by the style of the film as a whole (how its multiplicity of codes, including those pertaining to recruited voices, are orchestrated into a singular, controlling pattern); and (3) the surrounding historical context, including the viewing event itself, which the textual voice cannot successfully rise above or fully control. (28)

From this point of view, the “coding” of Chasing Asylum involves three strands. One constitutes its journalistic exposé: the mobilisation as evidence of the clandestine footage from inside the camps, along with the verbal testimony of the whistle-blowers who shot it. A second is the film’s emotional appeal to the viewer: its deployment of images and interviews to elicit sympathy for both detainees and whistle-blowers, including evidence from international locations as well as Nauru and Manus. The third strand lies in its mise en scène of interviews and found news footage, which is designed to evoke in the spectator a sense of outrage against Australia’s abusive policy, and to advocate for alternatives.

Orchestrating all these elements in Chasing Asylum, both textually and in its public circulation, is the authorial presence of Eva Orner. At the same time as speaking as a passionate and unapologetic activist, Orner has been at pains to craft a cinematic voice that would not only resonate with the converted: that is, Australians who see both a humanitarian duty and national benefit in inward migration and hospitality towards asylum seekers. She wants the message of Chasing Asylum to be heard also by a presumed Australian mainstream opinion, ranging from sceptics to xenophobes, that has not always been sympathetic to refugee resettlement. In her book about the making of the film, with this imagined audience in mind, Orner acknowledges that she was aware of a small percentage of asylum seekers who were not fleeing from persecution, but were looking for economic opportunities and enhanced life chances. That is why she made sure that her film concentrated on the conditions of asylum seekers’ detention, and on the way that the Pacific Solution has inhibited free speech in Australia, rather than arguing for or against the cases of individual applicants (195). Focusing on the state of the camps was a way of avoiding the thorny issue of who should, or should not, be granted asylum.

Consciously or not, this orientation aligns Orner with a widely used distinction, first drawn by the International Organization for Migration in the immediate post-war period, between “refugees” and “economic migrants”. It is a division that has become difficult, if not impossible, to sustain, as global inequalities in income, opportunity and financial security have deepened. It also plays into what performance theorist Emma Cox has pointedly named the “politics of innocence” (23): that is, the demand that any and all performative instances of asylum-seeking, whether by migrants in person or through media representations, have to be adjudged innocent of lying, or of exaggeration, or just of being overambitious in their aspirations, if they are to retain the sympathy of less vulnerable others.

To take an example of the “politics of innocence” that features in Chasing Asylum, Cox argues that the practice of lip-sewing represents a performative cry for help that simultaneously silences the cry and produces a strategy of self-harm that can continue indefinitely, especially if the performance cannot be remediated because access is denied to journalists (114–15). Protestations of innocence can be thus turned against the individual most in need of validation, as self-harm, as a last resort, is also concealed by forces of authority. In mid-2016, a panellist on The Project, a primetime television discussion programme in Australia, reacted to the release of secretly obtained documents that revealed the extent of brutality in the camps and the lack of redress for detainees:

They’re so horrible to read. I mean, many of them we can’t read in this timeslot, but there were three today that stood out for me. One, a guard threatening to kill a young boy once he left and moved into the community, a child being allowed to double her shower time in return for sexual favours, and a guard laughing at a child who had sewn her lips together. (qtd. in “Turning”)

Self-harm is always a form of exposure, an externalisation of the violence the self-harming person feels from social norms, bullying, invisibility and other forms of attack. For a protester, the act of self-harm may be a move in a political negotiation, or an expression of the impact of incarceration or torture on their mental health, or both. In any case, the embodied commentary constitutes a performative denunciation of the results of state-sanctioned violence, made painfully and dramatically visible to the state and to its citizens. For the young girl on Nauru, the knowledge that neither state nor citizens will actually see the “performance” of lip-sewing excruciatingly ratchets up the process of traumatisation.[4] In other words, uncommunicated and noncommunicative (lip-sewing) knowing is a challenge to the traumatised as well as to the observer. Self-harm inflicted by a girl in the highly politicised context of detention undoubtedly implies her unvoiced denunciation of state abuse. At the same time, this denunciation is magnified as it is turned back onto herself; it destroys her capacity to separate her body from the experience of denigration and shame. When a representation of injury, rather than actual self-harm, is on display, however, Cox argues that such mediated performances amount to “a rejection by the performers and activists of a dominant partialist politics” (118). The performers’ aim is to provoke spectators “to reconsider their stake in human injury, both present (in the bodies of performers) and absent (in the bodies of asylum seekers)”.

These insights suggest what is problematic about Orner’s decision not to comment either on the reasons why the men and women in the camps embarked on their risky journeys in the first place, or on the legal strength of their claims to refugee status. One has to respect a film that can provoke feelings of outrage or shame in Australian viewers, and move festival audiences to tears; but not if it does so at the price ofexacerbating the traumatic experience of detainees. The very effectiveness of Orner’s appeal to the emotions recalls the Slovenian philosopher Renata Salecl’s concerns about a press photograph of a young refugee girl during the Bosnian war of the 1990s. “When we see a tragic picture of a refugee we perceive in it a symbolic space in which we are the actors—we are the ones who are caring, compassionate and concerned”, argues Salecl (139). By putting such images into circulation, the media “creates the place in which we perceive ourselves as we would like to be seen”. In the case of girl with sewn lips on Nauru, as in the case of Salecl’s young Bosnian refugee, “one could say that the first tear runs when we see the poor girl and the second tear runs when we, together with all mankind, are moved by the fact that we are compassionate”. Meanwhile, the detainees who are the ostensible subject of the film come across as victims rather than agents, their existence narrowed down to protracted and embodied experiences of rejection and shame. Their bodies become the canvas of their despair. They are present in Chasing Asylum only in the form of remediated snapshots and off-camera voices. In a harsh interpretation, the film might be said to collude with the silencing of the men, women and children in the camps, by denying them even an autonomous to-camera denunciation of the conditions in which they are incarcerated. We, the presumed mainstream audience, do not engage with them face-to-face. We hear their disembodied words, we may weep for them, but we do not meet their gaze. Once again, the uncommunicated knowledge of despair is reinforced rather than undone.

The telling contrast to be drawn here is with another documentary filmed on Manus Island without the knowledge or permission of the camp authorities: Behrouz Boochani and Arash Kamali Sarvestani’s Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time (2017), which is discussed elsewhere in this issue. In order to ensure that their film presents and publicises direct detainee-witness testimony, Boochani (detained in the camp) and Sarvestani (the latter working from the Netherlands), took the principled decision to use the voices only of inmates (and local Manusians) who were willing to risk speaking on camera.

The Burden of Representation

In Chasing Asylum, it is not detainees but whistle-blowers who are shown speaking to camera, usually after they have left their employment in the camps as social workers, teachers and medical staff. For the most part, they are young and inadequately trained Australians, recruited in great haste in 2012 by charities like Save the Children, who were caught on the hop when the Labour government reopened the camps. Such was the rush that The Salvation Army even resorted to Facebook for their job ads.[5] “The people selected were inexperienced”, Eva Orner told The Guardian’s Brigid Delaney in April 2016. “They had no training or preparation.” And yet, these were the people who were willing to risk imprisonment in order to expose the deplorable state of the camps through their “camera activism” (Yu 59) and who, in many cases, again showed real courage by speaking out against detention at protest rallies in Sydney and Melbourne in 2016 and 2017. “These workers are the heroes of the story”, comments the journalist Brigid Delaney, “but there is very little glory in it for them”.

The footage provided by these whistle-blowers and their on-camera testimony are central to Orner’s orchestration of documentary codes to achieve her goal: that is, to make Australians feel compassion for the detainees, shame at their government’s actions, and responsibility to do something about it. One ex-worker recalls the joy shown by child detainees on one of the rare occasions when they received a gift. She describes a little girl rubbing the soft plush of a cuddly toy up and down her body. This young woman recounts her testimony as the expression of a sense of shame that her government should choose to incarcerate children in such an environment. Later, she explains how she feels an obligation to keep returning to the camp, even though working there is making her mentally and physically sick. This incorporation of shame as severe physical distress recalls the self-harm among detainees, which Emma Cox identifies as a response to incarceration. It also finds an echo in the growing incidence of physical and “moral distress” that social scientists are observing among frontline (and increasingly female) workers, when they take on the responsibility of caring for migrants in poor conditions (Hussein).

If the whistle-blowers are the heroes of Chasing Asylum, Orner nonetheless remains its organising presence. As well as articulating its cinematic voice, by mobilising the evidence of their images and words, she has also come to embody the film. She has spoken on its behalf in many interviews. She has accompanied it at screenings. On one memorable occasion in November 2016, on the day it was to be screened at the London Film Festival, she projected it onto a wall of Australia House in the Strand, and issued an online challenge to the High Commissioner, Alexander Downer, “daring” him to debate with her as the bearer of the film’s moral outrage. She also presents her own history as the biographical embodiment of the film’s message about making Australia compassionate again. “I’m a first-generation Australian”, says Orner, while acknowledging that she has been based in California since 2004: “My parents fled Poland to escape the holocaust. Only a handful of their two large families avoided being sent to death camps” (qtd. in Glass). She evokes her parents’ migration as an optimistic story of escape, arrival and successful settlement. “They made it to Australia and were able to build an amazing life here. That’s what makes Australia great”. It is this awareness of their good fortune, which she credits to Australia, that motivates Orner’s sense of responsibility: “As a child of parents who fled persecution I feel I have an obligation to do whatever I can to make Australia a welcoming country again” (qtd. in Glass). This obligation entails “a dual orientation to national and global universalist preoccupations” (Cox 157). Orner insists on imagining Australia as a compassionate and hospitable nation, which should manifest the universal virtues of compassion and hospitality, regardless of the prevailing global geopolitical situation.

In order to provide a cosmopolitan context that might help to explain Australia’s anxious and introverted Pacific Solution, Eva Orner visited asylum seekers’ sites of departure, transit, and limbo: Iran, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Indonesia, Cambodia. She wanted to interview the families of detainees who had died in the camps. She wanted to hear from people who had returned to their homeland, voluntarily or under duress, or who were still waiting to find some means of starting their journey towards Australia. In her Filmmaker’s Story, Orner charts the physical costs of this odyssey, which presented most dramatically in an extreme loss of weight and a frozen shoulder (256). It was after a trip to Kabul, a place she already knew well but where she felt resentful at the need to cover up and at the lack of courtesy shown to women in public places, that her shoulder became unbearably painful. Despite receiving treatment in Dubai and then in Melbourne, and despite her determination to travel on “to India, Burma, and Israel”, Orner records that “the pain was actually getting worse, and my movement was becoming very restricted. I was having trouble putting on a shirt or a bra, and my arm was permanently wrapped in a sling. I had no option but to go home” (257). Once back in the States, her cumulative symptoms were diagnosed as indicating post-traumatic stress disorder.

Orner’s deteriorating health revealed something more than an acting out of the suffering she had witnessed in the island detention centres and the stress of managing the clandestine filming. It also embodied a post-memory syndrome in relation to her parents. Somatically rather than metaphorically, she was bearing the weight of accumulated suffering on her shoulders. In writing about the film, Orner takes on the burden of the refugee, although, despite her fierce independence and obvious competence, this entails a counter-intuitive retreat into a childlike dependency on others. She manifests that dependency as she becomes sicker and more in need of professional assistance. When she talks about going home, her tone is apologetic and she appears to feel guilty that she has not managed to include “India, Burma, and Israel” in her punishing schedule. Even though no child’s voice is heard in Chasing Asylum, the filmmaker speaks for her own child-self. It is as if she too were a refugee, away from home, and, at the same time, a child who is failing in some unspoken chiasmic obligation to others.

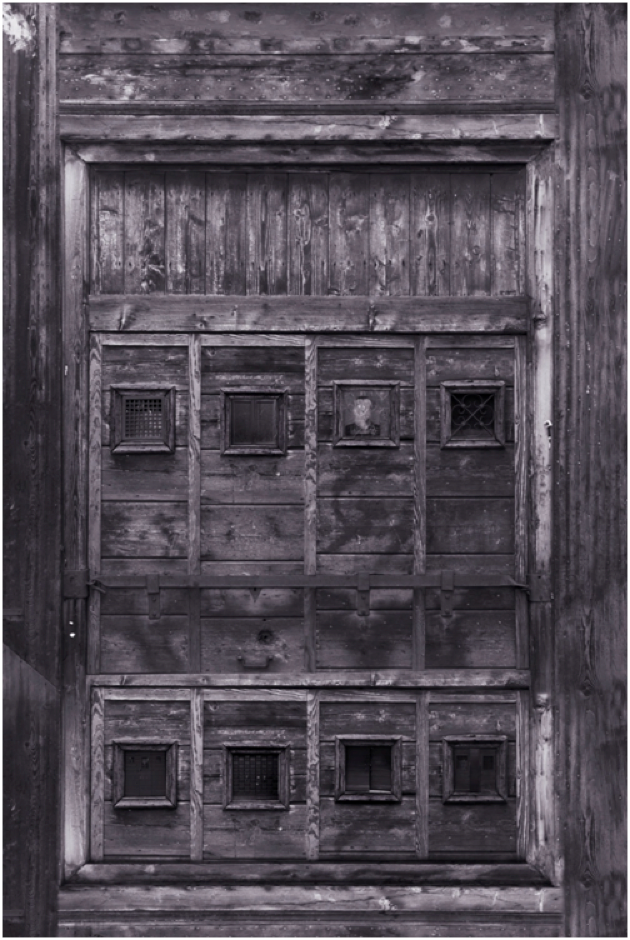

Figure 1: Blurred shot of a child in the camp. Chasing Asylum (Eva Orner, 2014). Nerdy Girl Films, 2014. Courtesy of Eva Orner. Screenshot.

Children have a somewhat spectral presence in Chasing Asylum. Although there are numerous comments about their welfare from voices on the soundtrack, the child detainees themselves do not speak. When they appear on camera, their faces are obscured, as is common practice nowadays, in order to hide their identity. One small child stands outside a tent (Fig. 1). Another sits on a piece of concrete and watches adults talk. These children are both witnesses to, and subjects of, the conditions that the film documents and condemns. As mobilised by Orner, their small presence functions to produce “raw visibility”; that is, according to John Corner, such images assert political content, rather than making an argument, whether using voice-over or other words and text, to prove their salience to the task of “documenting the political” (115). As mobilised by Orner, the pictures constitute a critique of state functions and political decisions. The children are rendered political by their very presence in a place where they should not be.

And yet, the politics implied by this presence of children comes across as somehow unfinished. The child standing outside the tent-like shelter looks down a short dusty passageway towards the camera, probably towards an adult speaking to her. She may or may not realise that a camera is there filming her. In any case, what is captured in this shot is less the child herself, than the space between us and her, between the adult sensibility of the viewer and the physical reality of the child in the camp. Although physically present there and then, and visible in the film, she nonetheless remains mysterious to us, suspended between an indexicality of suffering and imprisonment and an almost painterly invisibility, accentuated by the blurring of her face. The observable and felt space between spectator and child produces a degree of perspective, but at the same time it induces a response of incomprehension and uselessness. The space of childhood on Nauru is detectable mainly through its agonising thinness, and through the tunnel vision of incarceration. In terms of Peirce’s (and Cowie’s) discussion of indexicality and the real, we might say that, if meaning emerges from the triangulation of “object, sign, and an interpretant”, then here meaning—or the lack of meaning—is determined by the interaction between the actual child detainee (object), the moving photographic image of the child (sign), and the place of children in the Australian cultural imaginary (interpretant) (Cowie 30). This young girl is filmed to indicate the historical cruelty that imprisons her. Yet, her blurred and distant figure is simultaneously the object of the image and its interpretant. The space on screen does not signify, so much as evacuate, any settled meaning from the image and its assumed interpretation. I find myself noticing that the orange of the child’s shoes and the orange of the pedestals holding up the fencing are identical. Is this child becoming her own prison? What should we learn, or what may we infer, from her silence?

Obligation

In mid-2016, The Guardian releaseda video in which three teachers, who had worked with children on Nauru, talk about the psychological and emotional deterioration they observed in their pupils as a result of their incarceration. One teacher expresses the wish that she could do something to “save” the children and transplant them into a “normal” life in Australia. Another speaks about her fantasy that they might be released and that she might “bump into them in Woolies” (the Australian nickname for the Woolworth supermarket chain) (Wall and Farrell). Even as they speak, there is a hesitancy suggesting that these teachers already know that they cannot meaningfully “save” anyone caught up in this system. And the way that they speak, their capacity to imagine a better alternative outside detention, is expressed through an “affective economy” (Ahmed) that is peculiarly Australian: they talk about the freedom of children to run around on grass reserves or to hang out “in Woolies”. This cultural imaginary incorporates the very Australian principle of a “fair go”. For mainstream Australian opinion, however, unless there were to be a massive shift in the perception and understanding of asylum seekers, no leap of imagination seems possible that could make the connection between the reality of the desolate child, blurred and silent in a passageway between tents on Nauru, and the normative imagery of children living happily on a settlement visa in Sydney, Brisbane or Melbourne—a disconnect poignantly captured by the teacher’s shorthand of “in Woolies” and horrifically underlined by reports in 2018 that children detained on Nauru are not only self-harming in unprecedented numbers, but are using Google to search for information about how to commit suicide (Farrell, “Refugee”).

This brings me back to the aesthetics and ethics of Chasing Asylum: its claims to represent the reality of what is happening on Nauru and its ambition to “shame Australia” into changing government policies on asylum seekers and detention. I have suggested that the film’s capacity to achieve those ambitions is constrained by its form and voice as a particular type of documentary. Thus, in its most directly political strand, Chasing Asylum attempts to expose the cynical hypocrisy of politicians defending the Pacific Solution and its successors. It does so, cinematically, by juxtaposing their statements against the distressing footage from the camps, the testimony of disillusioned charity workers and rough-and-ready security personnel, and interviews with critical “talking heads”, such as the former Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, and the journalist, David Marr. The problem is that these politicians consistently usurp their critics’ language about the obligation to “save the children”. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott is shown claiming that the detention of children is a humanitarian intervention, insofar as his signature policy of “stopping the boats” had successfully undermined the people-smuggling industry, prevented loss of life at sea, and enabled Australia to develop its refugee resettlement program (Reilly).

In reflecting on the concentration camps and the extermination camps of the Third Reich, Giorgio Agamben draws an important distinction between ethics and law: “To assume guilt and responsibility—which can at times be necessary—is to leave the territory of ethics and enter that of law”, he writes (151). He then introduces the metaphor of the door, as both threshold and barrier, to stress what is at stake in making that move: “Whoever has made this difficult step cannot presume to return through the door he has just closed behind him”. Chasing Asylum, I would argue, remains within the sphere of ethics. It aims to provoke “shame” rather than “guilt” both in its audience and (if it were listening) the Australian government. Shame entails an awareness of not living up to one’s own moral standards or aspirations. Guilt, as Agamben implies, involves the responsibility one owes to another, whom one has wronged.[6] There is no going back from law to ethics, because law involves social and political processes that supersede individual feelings.

The High Commissioner in London had nothing to lose by ignoring Eva Orner’s protests outside Australia House and her challenge to a debate. Her ethical outrage packed no legal punch. Similarly, Australian policymakers and politicians react to the concerns raised in Chasing Asylum by repeating, in hollowed out form, the words of their critics. In doing so, they effectively close the door on the question of their potential legal culpability, and limit the debate to technical questions about the quality of care in the camps, the speed at which detainees are processed, and the very idea of punishment. It becomes an argument about whose pain and whose ethics is the more persuasive. The legal obligation to care for refugees and to educate and house children adequately is occluded.

Perversely, it may be that the only people liable to any sort of legal comeback in this affair are the whistle-blowers who took on the ethical responsibility of making public their damning evidence about the scale of abuse in the camps. Although, as noted earlier, Australia has signed many declarations on human rights, both universally and with specific regard to refugees and children, it has not enacted these conventions in domestic law. That is why the security company running the camps, Transfield Holdings, could brush aside accusations that its employees had committed “breaches of ‘human rights’ and other ‘international laws’” (Farrell). Transfield felt secure that no action could or would be taken: “While OECD guidelines allow for complaints to be made to the Australian government, in the unlikely event the Australian government recognised a complaint about the company, it has no power to enforce any finding” (Farrell). The criminologist Patrick van Berlo shows how Australia’s arrangements with Nauru and Papua New Guinea likewise sidestep potential culpability. By offshoring the camps to sovereign nations outside its jurisdiction, the government makes it difficult to establish who is responsible for what, and almost impossible to enforce legal accountability. The tunnel vision of dissociation that Agamben describes, and that is materialised in the child’s blurred stare down the passage between tents in Chasing Asylum, sees only our shared shame and the diminution of our humanity.

The Non-Representational Turn

In a thought-provoking article on the ways in which documentary film engages with the experience and category of trauma, Finn Daniels-Yeomans addresses the same issues about indexicality and ethics in documentary that are my concern here. Trauma presents a test case for documentary, not least because what makes an event traumatic is that it “cannot be placed within the schemes of prior knowledge” and therefore “occupies a space to which willed access is denied” (Caruth 153, 151). In other words, trauma resists representation, and so necessarily resists being captured by conventional forms of documentary: it “simultaneously demands urgent representation but shatters all potential frames of comprehension and reference” (Guerin and Hallas 3). Attempts to deal with trauma in nonfiction film have therefore tested the very limits of documentary’s (supposed) indexicality. Finn-Yeomans cites Linda Williams’s article on Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) as an example: she explores the film’s self-reflexivity, its deployment of the medium’s aesthetic techniques, and the way that it undercuts documentary’s cognitive norms as it attempts to get the measure of its subject matter. It is only by insisting on its indexical limits, as Finn-Yeomans summarises Williams’s argument, “by offering wilfully fractured, equivocal and partial visions”, that documentary can evoke the “receding horizon” of traumatic experience (88; Williams 12).

This approach does not go far enough for Finn-Yeomans, because its conception of documentary is still “configured chiefly in representational terms” (88). As he sees it, the old conventions and techniques of mimetic representation, didactics, third-person voiceover narrative, and descriptive documentation (ficto-documentary being one form of this) are neither sufficient nor appropriate for capturing the emotional, political or intellectual substance and depth of traumatic experience. His preferred alternative is an “affect-based, non-representational framework”, within which the elusive nature of such experience can be conveyed, without any elision of trauma’s “intimate violences” (86). This nonrepresentational aesthetic sets aside representation, indexicality and meaning in favour of a Deleuzean programme of materiality, affect and somatic immediacy. It is in his shift from “the cognitive or explanatory language of representation” to “the material relatedness of viewing body and world-on-screen” that Finn-Yeomans restates my question about the work’s claim on the spectator: that is, in his terms, “the multivalent operations of documentary textuality” (89).

Although the production and exhibition of Chasing Asylum might be seen as a performative act, and not just as a representation, insofar as the film’s explicit purpose was to make an intervention into the debate about Australia’s detention policies, its effectiveness is inevitably constrained by its form, its presuppositions and its reliance on documentary’s cognitive claims. Orner’s ambition to “shame Australia” is validated by the film’s images, and the evidential validity of those images is supposedly authenticated by their photographic indexicality. In other words, the images and sounds of Chasing Asylum are orchestrated so that the reality (or truth) of Nauru appears to speak for itself. It does not, of course, and it cannot—not least because the trauma of the detainees is not available for representation in such terms. Their marginalised presence in the film exemplifies what T. J. Demos, in his discussion of Steve McQueen’s short 2007 film Gravesend, calls the “conventional regimes of documentary practice”: they appear as “victimised objects, hopelessly stuck in the irrevocable reality of their situation and reaffirmed as such by their representation” (29).

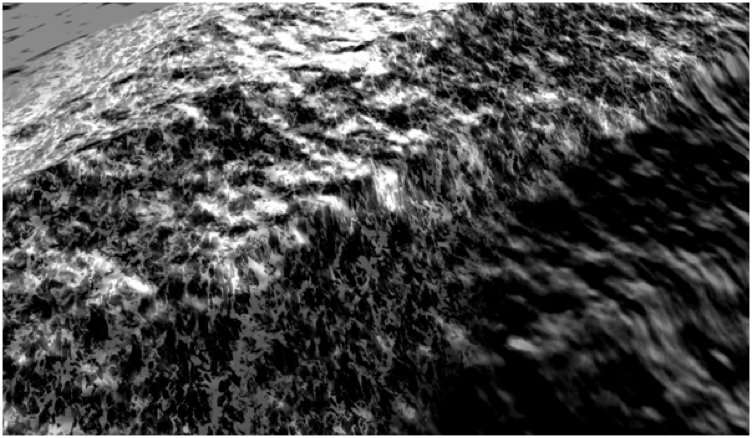

Figure 2: Door from Dolomites. Photographic installation, Dennis Del Favero, 2014.

Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 3: Door from Dolomites. Photographic installation, Dennis Del Favero, 2014.

Courtesy of the artist.

It is as an example of a work that conveys something of the trauma of asylum-seeking affectively, rather than through the emotional appeal of a narrative, that Dennis Del Favero’s Tampa 2001 offers a telling alternative to the obligation-based approach of Chasing Asylum. The work constitutes one segment in Del Favero’s ongoing Firewall series, which “explores the concept of the ‘door’ as a metaphor for the dynamic interaction between the human and non-human worlds” (Del Favero, qtd. in “Libidinal” 10). An earlier work in the series, Dolomites, explores the ambivalence of doorways by displaying images of Venetian entrances in small perspex boxes (Fig.2 and 3). In that iteration, the doors appear as puzzles: observable to the passer-by, but not apparently accessible. In Tampa 2001, the focus is on the interrelationship between thedoors that occupy a fundamental place in human society, and the doors that are also central to the natural world:

The oceanic waters surrounding Australia have always been perceived since white settlement as vast impenetrable “doors”, keeping human and non-human dangers at bay while protecting Australia’s inhabitants. 20th century Australia prided itself on opening its “doors” for those fleeing persecution. That all changed on August 29th 2001 when a Norwegian freighter, the MV Tampa, carrying 438 Afghan refugees, entered Australia’s territorial waters. The government responded by dis- patching its elite Special Forces to intercept this new “invasion”. (Del Favero, qtd. in “Libidinal” 10)

Figure 4: Tampa 2001 (Del Favero, 2011). Courtesy of the artist.

Tampa 2001 is a four-minute black-and-white video installation that features computer-generated images of ocean waves, projected in a circle onto the floor of the exhibition space. Using a step ladder or viewing platform, the spectator views this imagery under a dark curtain from a high point. It is an immersive experience, in which contemplation of the image—a digital simulacrum, not a photographic rendition—comes to evoke the Australian response to the arrival of refugees by boat thanks to the accompanying soundtrack. This is dominated by the deep boom of the ocean, as the waves turn over and crash back on themselves far out from a shoreline. There is a resonance between the visual rise and fall of the water and the rhythmic roar of the waves. A woman’s voice starts to speak: “Night drifts above the earth”. Her voice is overlaid with cries of seagulls, the occasional male voice speaking a language other than English, and a mechanical sound that might be the whirr of a helicopter or perhaps the outboard motor of a fishing vessel. A low musical drone, something between a wind instrument and a ship’s foghorn, enters and persists on its own track. The woman’s voice continues in whispered counterpoint to these quasi-diegetic lines of sound. It is both authoritativeand tentative. It speaks of doors and windows, of people “looking out” and of “the sudden stirring of limbs”.

In his exegesis of Gravesend, which deals with the links between the labour of Congolese miners and the use of the mineral they excavate, coltan, in high-tech mobile phones, T. J. Demos explains how Steve McQueen both fixes on “the indexical marks characteristic of documentary imagery” and at the same time, paradoxically, “depletes their substance, merely intimating the depiction of real bodies” (29). This notion of depleted indexicality is helpful in understanding Del Favero’s nonrepresentational evocation of boat people’s arrival in international and Australian waters, and their disappearance first through a media-blackout and then, through internment. Quite simply, there are no images of humans in the installation. It is just “us” on the ocean. The affect produced by Tampa 2001—a certain vertigo or queasiness, a sense of not knowing where one is, straining to hear and make sense of the voices and noises on the soundtrack—seems true to the processes of fragmentation, nonrepresentation, and occlusion of refugee voices that afflict the Australian discussion up until today. Del Favero’s image is at once singular and empathetically plural, nonorganic and mobile. The sea rolls brutally under our gaze while the soundtrack makes us aware of the humanity tossing on its surface, if we choose to listen. This is a document and a work of art that eschews emotional access, obligation or even legal claims to our attention. Rather, it offers an immersive acknowledgment of the terrifying ocean crossing from Indonesia, and the disconcerting sounds of rescue (by the Norwegian tanker) and subsequent betrayal (by Australia).

Let me, at last, draw together what the contrast between Chasing Asylum and Tampa 2001 reveals about documentary truth claims and audience engagement, within the historical context of Australia’s policies on refuge and detention in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

In Chasing Asylum, the use of clandestine filming by courageous whistle-blowers and the obligation-laden global travails of the main filmmaker result in a confronting and apparently transparent account of the Australian-funded camps on Nauru. The film reveals appalling conditions and frightening brutality. The men, women and children incarcerated there are shown to be languishing in limbo. However, these detainees are in communication neither with the camera, nor with the audience. They come across as “raw”, inert and unindividuated visual manifestations of the captive asylum seeker or refugee, rather than as “sites where the unknowable and the potential collide” (Demos 29). Their images are mobilised to impose a version of embodied obligation that is truncated by the space between “them” (the stock “victimised objects” of conventional documentary) and “us” (its spectators). The film fails to make a connection across the space between the detainees’ voice and the audience’s capacity to hear. Indeed, its very mode of exposure-through-secrecy requires that it does not. Audience responses are, therefore, not empathic in an outwards movement towards the other, but emotionally directed inwards, contained within an affective economy of shock and shame.

Compared with Orner’s strategy of using confronting revelation to arouse an emotional sense of obligation, Dennis Del Favero’s aesthetic is experienced as one of depleted indexicality and aesthetic austerity, or even humility. It aligns Tampa 2001 with the “derealization of representation” in Gravesend, a paring down achieved through Del Favero’s use of “direct signs” rather than “mediate representation” (Deleuze 8): the computer-generated seascape and the nonhierarchical structure of the soundtrack. The human souls adrift in their boat are invisible entities, whispering to us across a hardening border, the ocean door. As we peer down through the darkness, we hear snatches of men’s voices, we imagine the terrifying pitching sea as a boat creaks and what sounds like a helicopter buzzes overhead. If we were in Australia in 2001, we will remember the media image of hundreds of marooned faces looking up at the media helicopter filming them from above. With the cameras kept at an enforced distance by government edict, the faces were bunched and blurred, almost illegible as individual people. Tampa 2001 offers no redeeming fantasy of parochialised obligation to anonymous strangers, to whom we have not been introduced, and of whom we know little. Our task therefore becomes to listen, properly, to the soundtrack of the world we occupy, to the indexical production of silence, pain and irreparable betrayal (De Souza). And to acknowledge that there are some things we cannot hear easily.

Here, the ocean is not the ocean but it roils to a sound like the ocean. The voices of men are neither attributed nor owned, but their contrast to the scripted voiceover—the woman’s voice—suggests strongly that we must believe in them, or something like them, as radically different to script. The historical purchase of Tampa 2001 takes on greater resonance when the installation is set in the context of the Firewall series and its overarching metaphorical framework of the door. The video gives us hints of where we “are” and sonic clues to what might be “happening”, but it does not take us beyond doors that we ourselves have helped slam shut. Documentary is “nonactual”, in that we are obtaining some kind of access to moments and happenings that we did not ourselves experience (Cowie 36). Del Favero properly and politically limits that access to indistinct snatches of sound from a vantage point of oceanic vertigo. Whereas Chasing Asylum offers representation, emotion and opinion, Tampa 2001 engenders affect, intuition and a visceral sense that combines unreality, indeterminacy and unknowingness with creeping fear. To me, that seems rather closer to what can be effectively and properly conveyed through an external envisioning of refugee voice and refugee trauma during that dangerous sea rescue in 2001 and in the sad story of the betrayals that followed.

Notes

[1] For further detail see Gordon, Freeing.

[2] Although many of the internees have been awarded refugee status, they still remain on the islands at the time of writing as they await resettlement in a third country.

[3] One outcome has been a website providing information for asylum seekers (Chasing).

[4] In her influential 1996 book, Unclaimed Experience, Cathy Caruth argued that trauma arises not only from a causal event, but also from the despair experienced when the violence of the event is either ignored or communicated inaccurately (56).

[5] A private company, Transfield Services, took over recruitment from Save the Children in late 2015, as well as the day-to-day running of the camps.

[6] The families in Letters to Ali and Molly and Mobarak take on the burden of Australia’s guilt by trying to provide some recompense to Ali and to Mobarak for their treatment.

References

1. Agamben, Giorgio. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Zone Books, 1999.

2. Ahmed, Sarah. “Affective Economies.” Social Text,79, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004, 117–39, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

3. Australian Border Force Act 2015. Part 6 Secrecy and Disclosure Provisions. 21 Sept. 2016, legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00650.

4. Boochani, Behrouz. “Salim Fled Genocide to Find Safety. He Lost his Life in the Most Tragic Way.” The Guardian, 25 May 2018, theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/25/salim-fled-genocide-to-find-safety-he-lost-his-life-in-the-most-tragic-way.

5. Boochani, Behrouz, and Arash Kamali Sarvestani, directors. Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time. Sarvin Productions, 2017.

6. Boochani, Behrouz, Ben Docherty, and Nick Eversholt. “Self-Harm, Suicide and Assaults: Brutality on Manus Revealed.” The Guardian, 17 May 2017, theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/may/18/self-harm-suicide-and-assaults-brutality-on-manus-revealed.

7. Caruth, Cathy. Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Johns Hopkins UP, 1995.

8. ---. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History. Johns Hopkins UP, 1996.

9. Chasing Asylum: Information about Asylum Seeking. chasingasylum.com.au. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019.

10. Corner, John. “Documenting the Political: Some Issues.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 3, no. 2, 2014, 113–29, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/sdf.3.2.113/1.

11. Cowie, Elizabeth. Recording Reality, Desiring the Real. U of Minnesota P, 2011, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816645480.001.0001.

12. Cox, Emma. Performing Non-Citizenship: Asylum Seekers in Australian Theatre, Film and Activism. Anthem Press, 2015.13. Daniels-Yeomans, Finn. “Trauma, Affect and the Documentary Image: Towards a Nonrepresentational Approach.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 11, no. 2, 2017, 85–103, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2017.1281719.

14. Delany, Brigid. “Eva Orner on Chasing Asylum: ‘Every Whistleblower that I Interviewed Wept’.” The Guardian, 30 Apr. 2016, theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/apr/30/eva-orner-on-chasing-asylum-every-whistleblower-that-i-interviewed-wept.

15. Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton, Continuum, 2004.

16. Del Favero, Dennis, director. Tampa 2001. 2015.

17. Demos, T. J. The Migrant Image: The Arts and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis. Duke UP, 2013, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822395751.

18. de Sousa Dias, Susana. “(In)visible Evidence: The Representability of Torture.” A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film, edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow, Wiley-Blackwell, 2015, pp. 482–505, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118884584.ch22.

19. “Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951/1967).” UNHCR, 29 Sept. 2016, unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html.

20. “Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).” United Nations, 29 Sept. 2016, unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights.

21. Dunks, Glenn. “Chasing Asylum Is a Must-See Documentary Exposing Australian Detention Centres to the World.” Junkee.com, 27 May 2016, junkee.com/chasing-asylum-must-see-documentary-exposing-australian-detention-centres-world/79271. Accessed 13 May 2019.

22. Farrell, Paul. “Transfield Could Face Legal Action over Nauru and Manus Abuses, Group Warns.” The Guardian, 20 Sept. 2015, theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/sep/21/transfield-could-face-legal-action-over-naura-and-manus-abuses-group-warns.

23. ---. “Refugee Children on Nauru are Googling How to Kill Themselves.” ABC News, 24 Oct. 2018, abc.net.au/news/2018-08-27/refugee-children-on-nauru-googling-how-to-kill-themselves/10153568.

24. Glass, Steven. “Chasing Asylum: The Film the Australian Government Doesn’t Want you to See.” Asylum Seekers Centre, 27 Apr. 2016, asylumseekerscentre.org.au/chasing-asylum-the-film-the-australian-government-doesnt-want-you-to-see.

25. Gordon, Michael. “Six Days on Nauru.” Inside Story, 14 Aug. 2012, inside.org.au/six-days-on-nauru.

26. ---. Freeing Ali: The Human Face of the Pacific Solution. UNSW Press, 2005.

27. “Gravesend (2007)”, Schlauger Laurenz Foundation,14 Aug. 2018, stevemcqueen.schaulager.org/smq/en/exhibition/gravesend-2007.html.

28. Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth, editors. The Affect Theory Reader. Duke UP, 2010.

29. Guerin, Frances, and Roger Hallas. The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture. Wallflower Press, 2007.

30. Henderson, Mark, and Christine McAuliffe, directors. Tampa and Beyond. Video Education Australasia, 2002.

31. Hussein, Shereen. “Gender, Migration, and Poverty Pay in the Precarious English Social Care Sector.” Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW. Conference Presentation, 9 Aug. 2016, arts.unsw.edu.au/media/SPRCFile/Shereen_Hussein_Presentation_UNSW_2016.pdf.

32. Kuipers, Richard. “Film Review: Chasing Asylum.” Variety. 1 Mar. 2019, variety.com/2016/film/reviews/chasing-asylum-film-review-1201763518.

33. Law, Clara, director. Floating Life. Hibiscus Films and Southern Star, 1996.

34. ---. Letters to Ali. Lunar Films Pty Ltd, 2004.

35. “Libidinal Circuits: Scenes of Urban Innovation.” University of Liverpool, UK, 8–10 July 2015, www.stephaniedonald.info/files/LC Programme Web.pdf. Conference and exhibition programme. Accessed 2 Sept. 2019.

36. McAdam, Jane, and Fiona Chong. Refugees: Why Seeking Asylum is Legal and Australia’s Policies Are Not. NewSouth Publishing, 2014.

37. McQueen, Steve. Gravesend. Installation. 2007. 14 Aug. 2018, renaissancesociety.org/exhibitions/455/steve-mcqueen-gravesend.

38. Morris, Errol, director. The Thin Blue Line. Miramax Films, 1988.

39. Nash, Kate. “Exploring Power and Trust in Documentary: A Study of Tom Zubrycki’s Molly and Mobarak.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 4, no. 1, 2010, pp. 21–33, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/sdf.4.1.21_1.

40. ---. “Stealing Moments: Tom Zubrycki’s Molly and Mubarak.” Metro Magazine, 165, 2010, pp. 67–70.

41. Nichols, Bill. “The Voice of Documentary.” New Challenges for Documentary,edited by Alan Rosenthal and John Corner, 2nd ed., Manchester UP, 2005, pp. 17–33.

42. Orner, Eva, director. Chasing Asylum. Nerdy Girl Films, 2016.

43. ---. Chasing Asylum: A Filmmaker’s Story. Harper Collins, 2016.

44. Perera, Suvendrini. “A Line in the Sea: The Tampa, Boat Stories and the Border.” Cultural Studies Review, vol. 8, no. 1, 2002, pp. 11–27.

45. Ramaswamy, Chitra. “Chasing Asylum: Inside Australia’s Detention Camps Review–A Portrait of Hell.” The Guardian, 1 Mar. 2019, theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/nov/01/chasing-asylum-inside-australias-detention-camps-review-a-portrait-of-hell.

46. Reilly, Alex, “The Boats May Have Stopped but at What Cost to Australia?” The Conversation, 28 Aug. 2014, theconversation.com/the-boats-may-have-stopped-but-at-what-cost-to-australia-30455.

47. Richardson, Michael. Gestures of Testimony. Bloomsbury, 2016.

48. Salecl, Renata. The Spoils of Freedom: Psychoanalysis and Feminism after the Fall of Socialism. Routledge, 1994.

49. Smaill, Belinda. The Documentary: Politics, Emotion, Culture. Palgrave, 2010, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230251113.

50. “Turning a Blind Eye.” Media Watch, Ep. 9, 15 Aug. 2016, abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s4520092.htm.

51. Triggs, Gillian, and Australian Human Rights Commission. “Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Human Rights: Snapshot Report.”2nd ed., Arts and Humanities Research Council. 2017.

52. van Berlo, Patrick. “The Protection of Asylum Seekers in Australian-Pacific Offshore Processing Centres: The Legal Deficit of Human Rights in a Nodal Reality.” Human Rights Law Review, no. 17, 2017, pp. 33–71, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngw017.

53. Wall, Josh, and Paul Farrell. “‘You Wish You Could Save Them’: Teachers Describe Anguish of Children Held on Nauru.” The Guardian.10 Aug. 2016, theguardian.com/australia-news/video/2016/aug/11/you-wish-you-could-save-them-teachers-describe-anguish-of-children-held-on-nauru-video.

54. Williams, Linda. “Mirrors Without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary.” Film Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 3, 1993, 9–21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.1993.46.3.04a00030.

55. Wilson, Jake. “Chasing Asylum Review: Eva Orner’s Documentary Makes Concrete the Horror’s of Australia’s Immigration Detention Centres.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 Mar. 2019, smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/chasing-asylum-review-eva-orners-documentary-makes-concrete-the-horrors-of-australias-immigration-detention-centres-20160525-gp3csl.html.

56. Yu, Tianqi. “Camera Activism in Contemporary People’s Republic of China: Provocative Documentation, First Person Confrontation, and Collective Force in Ai Weiwei’s Lao Ma Ti Hua.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 9, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2014.1002251.

57. Zubrycki, Tom, director. Molly and Mobarak. Jotz Productions, 2003.

Suggested Citation

Hemelryk Donald, Stephanie. “Shaming Australia: Cinematic Responses to the ‘Pacific Solution’.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 18, 2019, pp. 70–90. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.18.06.

Stephanie Hemelryk Donald is Research Director, Centre for Culture and Creativity, and Distinguished Professor (Film) at the University of Lincoln. She was previously Lead, Grand Challenge on Refugees and Migrants, and ARC future fellow (UNSW) in Sydney Australia. Recent publications include There’s No Place Like Home: The Migrant Child in World Cinema (2018) and Childhood, Cinema and Nation (2017).