A Digital Archive Is Born: Revisiting the Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain Collection

Julia McDowell and Annie Nissen

Abstract

This paper explores the opportunities and challenges faced in digitising, presenting and preserving materials on cinemagoing collected during Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain, a pioneering inquiry led by Professor Annette Kuhn in the 1990s. Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive (CMDA) is tasked with archiving and digitising these extensive materials, including over a hundred audio-recorded interviews with 1930s cinemagoers and a wealth of related correspondence, documents and other memorabilia donated by participants. The primary focus of CMDA is to make these materials available online, applying the most appropriate formats to make them accessible and engaging to a global audience of both scholars and the wider public. Drawing on our experiences as a close-knit team, we describe the development of the project from two perspectives, that of web developer and that of archivist. Identifying key issues, we detail ongoing experiences and knowledge gained in the field, examining decisions taken in the early stages of the project that have enabled progression towards its goals. The challenges inherent in bringing such a valuable and unique set of resources into the realm of digital humanities are immense; we conclude by reflecting on lessons learned and offering fresh perspectives and insights to researchers undertaking similar work.

Dossier

In the early 1990s, Annette Kuhn began a pioneering ethnohistorical investigation into cinemagoing and cinema culture, looking at how cinema figured in people’s everyday lives during the interwar years in Britain. Throughout the course of her nationwide inquiry on the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)–funded Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain (CCINTB) project, she collated not only contemporary source material from the 1930s, but, more significantly, written and oral testimonies from surviving cinemagoers of the time, along with personal memorabilia donated by the participants, including film star autographs, postcards, diaries and scrapbooks.

Kuhn’s research has been formative for the fields of cinemagoing history and memory studies, with lasting impact on New Cinema History and film and cultural studies more widely (Everyday; “Heterotopia”). Interest in cinema memory continues to grow in the UK, with CCINTB and the resulting research inspiring many similarly funded Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) projects and archives, such as Cultural Memories and British Cinema-going of the 1960s (2013–2015) and European Cinema Audiences (2018–2021) (Ercole et al.). While these have benefitted from more recent twenty-first-century scholarly practices, the CCINTB collection has not yet been preserved or displayed in the manner it deserves.

Both within the initial project outline to the ESRC in 1994 and in the final project report in 1997, the need to create an archive from the collected material in both “electronic and paper form”, as well as finding it a “permanent home”, was highlighted, to help safeguard the availability of both material and data for continued scholarship and general interest.[1] While it took over twenty years for a viable proposal to emerge that would guarantee a more accessible and sustainable future for the archive, this temporal gap has nevertheless turned out to be advantageous for the material itself. Due to the time lapse between the original project and the current knowledge environment, the collection is now able to benefit from developments both in digital technology and in the fields of digital humanities and archive management. The archive material will therefore be made available on a far greater scale than originally anticipated, not only through free digital access, but also through the increased potential offered by digital tools today. Ultimately, this is likely to encourage broader usage by both academic and the wider public, far more than was envisioned when the original project was conceived in the 1990s.

Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive: 1930s Britain and Beyond

The CCINTB collection is currently being revived as part of the Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive: 1930s Britain and Beyond (CMDA) project, with a focus on newly archiving and digitising the material for future preservation, both online via a website, as well as physically within the Special Collections area at Lancaster University Library. Thanks to funding from the AHRC, the continuation and longevity of Kuhn’s work and the CCINTB collection have therefore been secured. CMDA also aims to build on the findings of the original project through conducting broader and more interdisciplinary inquiries, using NVivo qualitative data analysis software and geographic information system (GIS) software alongside a range of other digital tools to support this.

The three-year project, which began in Summer 2019, is led by Richard Rushton (Lancaster University) along with Annette Kuhn herself (Queen Mary University of London) and Sarah Neely (University of Glasgow). As two of three Research Associates (RA) on the CMDA project, we have been provided with the exciting opportunity of revitalising the CCINTB material and, as archivist and web developer respectively, we are responsible for organising, cataloguing, bringing online and coding the collection. The project is also supported by a third RA, Jamie Terrill, who, in addition to project management duties, is overseeing the majority of the scanning and file conversion work. Once the initial phase of cataloguing and digitising the archive is complete, there will also be a focus on dissemination of both the digital and physical collections to encourage wider academic engagement, alongside facilitating a range of public-facing activities.[2] The aim here is not simply to promote its use to researchers and the wider public, but also to encourage contributions to enhance, develop and extend the collection further. In keeping with our commitment to provide shareable data, we are also collaborating with Lancaster University Library’s new digital platform, Lancaster Digital Collections, which forms part of an institutional link with Cambridge University’s Digital Library platform, to enable searching and zooming of high-quality digital versions of the archive materials and access to the Mirador image viewer.[3]

While recognising the uniqueness of the project, not least because we have the privilege of working with Annette Kuhn as the originator of the research, some of the difficulties we have faced are universally applicable within the digitisation and archiving of project material of this nature. The autoethnographic approach we describe here, therefore, not only illustrates our own practices and methodologies in dealing with the collection, but also explores some of the difficulties we have faced and the knowledge we have gained in the fields of cinemagoing history and memory studies. Prior to taking up our roles on this project, our individual research areas were not related to either of those fields and we have consequently approached the collection material from a largely constructivist angle. Our multi- and interdisciplinary backgrounds have nevertheless enabled us to assess the material objectively, and we believe that our experiences with the development and creation of the (digital) archive and the reflective insights addressed in this paper will be valuable to both archive and digital developers within the humanities and social sciences, as well as to researchers in the cinema memory and history field.

First Impressions and First Steps

Although the research resulting from CCINTB has populated and inspired the field of historical cinema audience research and memory studies,[4] the material itself has remained largely inaccessible to scholars, hidden away in storage boxes and cabinets in the depths of Lancaster University Library’s Special Collections.

Figure 1: The original CCINTB project’s filing cabinets.

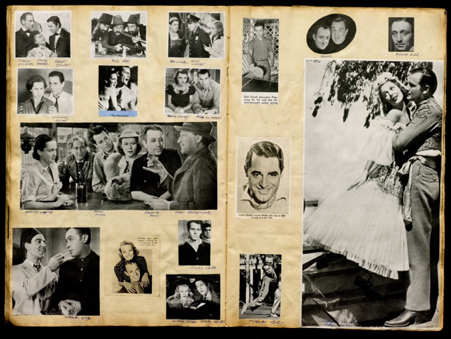

Broadly, the content of the collection comprises over a hundred audio-recorded interviews, over two hundred participant files with a multitude of related correspondence including letters, questionnaires (totalling over three hundred), and researchers’ field notes, as well as other documents. In addition, there are contemporary publications and material used during the CCINTB research phases, as well as various types of memorabilia donated by participants, ranging from postcards, autographs and music sheets to diaries and scrapbooks, along with the odd novelty item, such as a Jeannette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy Calendar and a Deanna Durbin Paper Doll.

Figure 2: Page from Doreen J. Lyell’s 1930s Scrapbook.

From an archival standpoint, it appeared that, on a closer look, the state and management of the collection were in greater disarray than originally anticipated, and the extent and nature of the materials were only gradually revealed whilst exploring the files and boxes. While a physical index of the collection existed, and innovatively for its time, a limited database using FileMaker Pro, these were partially incomplete, meaning that the original administrative system needed to be revised and updated. Assessing the material in terms of form rather than content seemed to be the logical starting point in this case.

Certainly, at the beginning of our work on CMDA, there was some uncertainty in determining the best approaches and practices to develop and create the archive. This was primarilydue to our varying levels of knowledge and expertise, as well as our gradual understanding of the original project, the extent of the collection, its organisation and methodologies. Familiarising ourselves with affiliated academic resources via the History of Moviegoing, Exhibition and Reception (HoMER) Network, along with exploring existing digital archives and other cinemagoing projects, such as the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum (“Explore the collection”) and the Italian Cinema Audiences website, helped orient us in the initial stages of the project. Through regularly discussing the collection with the project team over the following few months, we continued picking up the associated concepts and language relating to cinema history and 1930s cinemagoing in a gradual process of “legitimate peripheral participation” (Lave and Wenger 29), whereby novices learn the culture and norms of a community of practice by being around those with greater expertise.

From the perspective of a web developer with little experience in the field, however, it was only through reading some of the correspondence received from participants and, in particular, listening to some of the interviewees reminiscing about their cinemagoing, that the “golden age” of cinema and what it meant to 1930s cinemagoers came alive. This reflects the view of Irena Řehořová, who, while discussing the role of the Czech National Film Archive in shaping cultural memory, suggests that audiovisual works “by offering an immersive, emotional visual experience […] enable the viewers to experience the past in a completely different way than for example written texts” (187). We would argue the same is true of audio works, and in these interviews, through the subtle manner and skilful questioning of the interviewer Valentina Bold, the testimonies of those whose lives encompassed a particularly fascinating period in Britain’s history can be heard: the hardships encountered in living through the “Hungry Thirties” juxtaposed with the glamour of 1930s “picture palaces”, film stars and the escapismprovided by Hollywood and cinema in general. It was not only the cinema, film star and film preferences that we learnt about; we also gained an appreciation of the day-to-day lives of those participants, their families, their politics, their outlook on life and what was important to them, all set against the backdrop of the onset of the Second World War. Listening to the participants themselves talk about their experiences lent powerful authenticity to their stories, and was key in informing both our understanding and, as a corollary, the organisation and display of data on the website, the design of the database and the presentation of the material overall.

Research and Service

As with any project, staying within the proposed scope can prove problematic as new directions and possibilities emerge during the research phases. For CMDA, the research phase is preceded by the management of the existing collection. Rather than cataloguing and digitising the material at the end of the project, as is so often the case, our process actually began by organising, cataloguing and digitising. Eric Hoyt, director of the Media History Digital Library, makes a pertinent case for the scholarly value of digital collections and the process of digitisation and curation as the “convergence […] between ‘research’ and ‘service’” (367). This interchange between service and research has become increasingly apparent during the progress of CMDA, as the content of the collection has informed our practices of dealing with the material. Our initial lack of familiarity regarding not only the extent of the collated material, but also its scholarly context, resulted in us approaching the tasks ahead as more of a service. By engaging with the material and its contexts, however, it has become apparent that developing and creating the archive is in itself a research activity.

Rather thanpresenting the material in a purely one-dimensional manner, emphasis has been placed on creating an interactive and interrelated archive in order to not only effectively show the value of the collection, but also to represent the individual contributions. Bearing this in mind, CMDA aims to give precedence to the participants, creating profiles and building the collected material around them, their experiences and memories of cinemagoing. One of the ways this is being achieved, for example, is through the new accessioning procedures.

Although individual items had previously been accessioned within the original project, none of the material had since been listed within the University Library catalogue, giving us the opportunity to provide new accession numbers whilst cataloguing the material using the Ex Libris Alma library management solution. Planning and engaging with reaccessioning the material has simultaneously allowed for the emergence of a clearer organisation and refocusing that benefits both the physical and the digital archive in terms of creation and presentation. One of the issues here, however, was that the old numbers had already been used in CCINTB research outputs, but this was readily dealt with by including the original number within the new entries and headers, meaning that they are still accessible for anyone searching for archive items via the old accessioning system. The original accession was numerically comprised of the year, an individual number assigned to the participant and numbers which signalled the amount of material connected. For example, Margaret Young, who was the earliest participant, contacting CCINTB in 1992, was 92-1; and one of the several books she donated was 92-1-20d (Movie Cavalcade by F. Maurice Speed). The new accession system makes use of, and also enhances the old system by distinguishing contributor and contributions more clearly (in this instance respectively as MY-92-001 and MY-92-001BK003). The type of material, such as ‘BK’ for book, and also the participant, through the use of his/her initials, is therefore more clearly identified.

One of the priorities of the cataloguing and archiving has therefore been to place even greater emphasis, through the presentation and organisation of the content, on the participants and their contributions to the project and the collection.[5] In An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Culture Memory, Kuhn herself highlights the importance of the participants, noting that their “accounts constitute both the engine and the product of the investigation” (7–9).

With each “sigh” and “laughter” we have heard during an audio interview along with the experiences of cinemagoers themselves, as both researchers and attentive listeners/readers, we have also felt connected to the person behind the memory. By organising and presenting the material more emphatically through its connection with the participant, we intend to create a stronger, more vivid, bond as the archive user gets to know the participant through the material. Individual case studies can also be conducted more readily as archive users are able to search for participants directly and identify connected materials more easily.

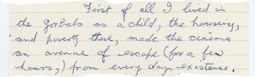

Figure 3: Extract of letter sent to CCINTB by Sheila McWhinnie, Glasgow.

Many participants provided very detailed descriptions of their journeys to the cinemas of their youth, with some giving a “walking tour” of all the cinemas located in their particular area. These “memory stories” offer a rich resource for those interested in exploring how cinema memory can operate as a “specific form of cultural memory” (Kuhn, “Heterotopia” 17); we intend to augment this connection between participant and archive user by investigating how geographical GISmight be used to help embody the links between geographical locations and participants’ memories in prompting recollections and shaping memory talk. Initial work on researching suitable platforms to present this is underway, with functionality trialled using the Leaflet app marking it as the most promising contender for incorporation within the website.[6]The first step in building an effective website is identifying your target audience and determining how best to engage them. With outreach and impact forming a key part of the project’s objectives, the dual foci of the website are not only to make the CCINTB materials easily accessible to both academics and the wider public, but also to draw visitors in to explore the materials and to raise awareness of the collection more widely. In the project’s application to the AHRC, the target audience was briefly described as: (i) national and international film historians and memory studies researchers; (ii) local historians; (iii) community groups, such as creative writing groups; (iv) the general public, both film lovers and amateur film or cinema historians; (v) audiences from outreach activities; and (vi) museums and archives, for example the Mass Observation Project. Following recent dissemination opportunities, including local school talks and other presentations, the target audience has since been augmented to include secondary and further education, as well as Digital Humanities projects/specialists and family historians.

To act as a focal point for initial project team discussions, particularly in terms of honing ideas and expectations for the website, a demo version was created using the WordPress blogging platform. The decision to use WordPress to develop the website was taken both for future-proofing purposes, due to its ease of editing once the funded project comes to a close, and its ability to communicate with the PHP programming language and MySQL database underpinning the search engine. The creation of a number of demo pages using a variety of logos and theme colours also helped focus us on those navigational and functional elements that are key to end-user satisfaction, as well as guiding the search for appropriate material from the collection to include on the site, to reflect the essence of the project.

One of the outputs resulting from those early project team discussions was the creation of a digital timeline for CCINTB, detailing the steps taken that led to the inception of the original CCINTB enquiry and summarising CCINTB’s principal milestones up until the launch of the CMDA project (“CCINTB Timeline”).[7] In line with the tenets of constructionism(Papert), where one gains deep understanding of a topic by creating digital artefacts about it, the timeline was one of the first areas on the website to be developed with Professor Kuhn. In addition to providing links to selected articles, books and interviews by Professor Kuhn during that period, deep links to the audio recordings and transcripts of various participant interviews and letters that fed into these outputs are now in the process of being added, to enhance verifiability as well as for general interest. This task was not only invaluable in providing us with an overview and understanding of the underpinnings of the CMDA project and the breadth of work that preceded it, the provision of the timeline on the website can now also serve to provide insights into the kinds of steps that lead to the formation and building of a large, multifaceted academic research project. To this end, we are in the process of developing a similar timeline to document the progress of CMDA.

Resulting from useful comments received in our first Steering Committee meeting, discussions also ensued on the merits of having two entry points to the site, or two routes through it, one for professional researchers and one for the wider public.[8] This idea was eventually thrown out as likely to prove unwieldy in practice, in favour of an emphasis on the use of clear pointers to content and functionality throughout the site, with the aim of making it intelligible and accessible to all. This key focus on usability also specified the need for both simple and advanced search mechanisms for querying the project database, which will act as repository for all digitised material from the collection. Once core functionality and a skeleton navigation system for the site had been agreed, attention turned to its visual appeal, often referred to by web designers as the “look and feel”. Here, an emphasis has been placed on creating a simple yet flexible design for the user interface that facilitates both the easy incorporation of new areas, and the showcasing of key items from the collection as digitised versions become available.

Figure 4: Screenshot of the CMDA project website.

Digitisation, Transcription and Database Considerations

Seeking to bring such a wide-ranging set of data sources online, while ensuring best practice is being adhered to within the project’s timeframes, has brought many challenges, both technical and conceptual. This is not only due to the varying quality of certain items in the physical collection, such as issues relating to the digitisation of degrading audio tapes, 35mm film and picture books, but also relates to limitations around the software and hardware available in the 1990s, such as that used to aid file management and data analysis. We think it unlikely that our project will be the only one to face such challenges, and the following section therefore outlines a few examples to illustrate the kinds of issues we have faced, the decisions we took and the justification for them.

In the case of the digitisation of hand-written letters, postcards, film strips, books and other visual elements, it became clear early on that three versions of each item were needed to suit different purposes:

high-resolution .tiff required for archiving and conversion to jpeg2000 (600dpi) for Lancaster Digital Collections, to facilitate high-quality display and zooming;

lower-quality .jpeg for the website (maximum 1000px high for portrait, and 1000px wide for landscape) to balance reasonable quality with reasonable loading speed;

thumbnail .jpeg (to be returned from database searches to launch larger versions).

In hindsight, while it might have been more efficient for these items to be digitised, converted and accessioned as part of a streamlined process, this did not always happen in practice. Reasons for this varied from requests for certain materials to be made available on the website at speed, to issues relating to a lack of clarity around requirements for Lancaster Digital Collections.

Agreeing a house style for preparing the CCINTB interviewtranscripts was marked as a priority at the beginning of the UK COVID-19 lockdown period, both to ensure that transcripts were standardised using appropriate and recognised transcription conventions, and to maintain consistency across transcripts. This process involved several weeks of negotiation among project team members, particularly around the various uses of emphasis, including: (i) the use of capitalisation or bold to denote a heightening of tone in an interviewee when expressing surprise or delight; (ii) the use of italicisation of film titles; (iii) the use of underline to denote the names of cinemas; and (iv) the use of single quotes for book or magazine titles. Discussions also focused on whether to retain the original phoneticisation of participants’ transcripts, with particular reference to dialect, as the removal of this was felt by some to rob the transcript of a certain level of authenticity.[9] Cognisant that some participants had stated a preference for their transcripts to be rendered in Standard English, and aware that coding the search engine to accommodate all forms of expression was likely to prove prohibitive within the time scale, a decision was taken to standardise all transcripts to remove phoneticisations, on the understanding that the original phonetic transcripts would remain available in physical form via Lancaster University Library. Certain words that were part of the localised terminology, such as the use of “messages” to refer to “shopping” in Glasgow, were retained with a gloss in square brackets, and this approach was also taken where a cinema was referred to by a nickname or when a film title had been misremembered.

Alongside decisions relating to house style, discussions also centred on what metadata to include for files accessed via the website and those on the University’s library system, not only in terms of providing contextual information, but also highlighting any interrelations and interlinking of material. Headers for interview transcripts (both PDF and audio-synced versions) therefore provide information relating to the name of participant(s) and interviewer, location and date of interview, name(s) of transcriber and standardiser, length of audio, audio quality as well as accessioning references (original and current) for all transcripts and audio tapes associated with a particular interview. Similarly, document transcript headers provide information about the author, the intended recipient, the date, name of transcriber and standardiser, the document type (for example, letter or essay), the number of pages, and some contextual notes such as the reason for writing. In addition, each interview and document has its own synopsis and a listing of any cinemas (with addresses), films (with dates) and star names mentioned. This data is being passed to the library for inclusion in their systems and feeds into the database and QDA work.

In keeping with our overarching commitment to preserve anything that might be considered of value to future researchers, we have aimed to stay true to the biographical contexts of the original participants where possible. This has been feasible primarily due to the requirement on all CCINTB interview participants to complete detailed consent forms, including an option to hold back personal data for fifty years (although only one participant opted to do so). Following a meeting with Lancaster University’s Information Governance Manager at the outset of the project, our policy has been to redact the dates of birth, addresses and telephone numbers of participants in both the CCINTB interview and document transcripts, including “blurring out” equivalent details in the scans of documents. In addition, we also redact the surnames of any persons mentioned by participants in the course of their interviews to preserve anonymity and are operating a “take-down” policy should family members raise any objections to the information that is available online. The original, unredacted physical copies will be made available via Lancaster Library, providing appropriate permission from the participant was granted. In addition, aware that some of the prevailing views and opinions expressed in the interviews may not meet “today’s norms and expectations”, a decision was also taken as part of the standardisation process to include a brief disclaimer at the top of each transcript, rather than using the blunt tool of redaction, to “stay true” to the data (Glaser and Strauss).

As regards the CCINTB audio-recorded interviews, many of the original tapes had previously been converted to .wav digital format, with a separate file for each tape, and corresponding separate files for transcripts. In addition to combining the transcript files into one document, the audio is also being combined to create one file for each interview, sometimes necessitating the joining of audio from up to three audio cassettes (with two sides each) per interview. These files are then being converted from .wav to .mp3 format (128kbps) for syncing and indexing with the Oral History Metadata Synchronizer, with Lancaster University Library requesting use of the higher-quality .wav files for archiving purposes.[10] Lancaster Digital Collections are still in the process of determining audio functionality and formats, and so these files may require a further conversion from .wav format at some point in the future.

When the CCINTB interviews were recorded and transcribed in the 1990s, not only was the audio recording technology inferior to that available today, with microphones less sensitive, for example, and audiotapes snapping, whistling or squeaking, the process of transcription itself was more cumbersome. Unable to take advantage of the nimble flicking back and forth to check “difficult to make out” audio extracts that we can do today, this has resulted in some transcripts including numerous passages marked as inaudible, and some where the transcription itself is inaccurate.

Following the standardisation process, syncing the audio with the transcripts has brought any divergence between audio and transcript into high relief, and it has since been accepted that all interview transcripts must be matched against their audio prior to syncing. This has added another unanticipated layer of complexity to the process, and is likely to add many hours of work. Given the project’s commitment to best practice and the importance of providing verifiable data, this is felt to be an appropriate and valuable use of time.

Initial work on the relational databaseand the search engine began while still in the early stages of developing an understanding of the field.[11] Initially, it focused on testing communication between the website and a test MySQL database, using the PHP programming language to query the database and output results on a dummy webpage. Once an interface had been created, and it had been confirmed that searches could be conducted on particular tables with results correctly outputted, research was carried out to establish the best mechanism for open keyword searching, as these were likely to be the most intensive in terms of processing power.[12]

Alongside the need for a deeper awareness of the field and the nature of the collection itself, it became clear early on that further progress on the digitisation and file-naming process of archive materials was required, both to inform the design of the database and to enable the incorporation of digitised versions within it.[13] Similarly, as qualitative data analysis (QDA) of the materials was intended to feed into the generation of keywords for the database and to inform the criteria for the search engine, further work on these aspects of the database have been postponed until this has taken place. As from September 2020, the QDA process is now underway, with much anticipation on what new findings this may uncover, and what innovative research streams may result.

Preservation and Presentation

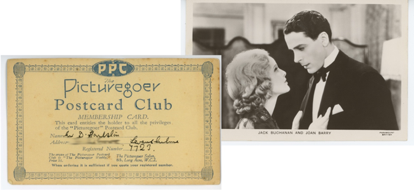

The dual role of any archive is not only to provide access to materials, but also to preserve them for the future. With the CCINTB collection waiting to be revitalised, proper storage and display within the physical “Special Collections” area has been one of the main objectives of the archival role, with this process also informing further aspects of presentation and organisation. Many of the items which will be prominently highlighted within the collection were rather haphazardly kept in the forms in which they were originally donated, usually brown paper envelopes (to the concern of any archivist). This included Mancunian film fan Denis Houlston’s incredible collection of signed autographs and one hundred and sixty two postcards from The Picturegoer Postcard Club, depicting a wide variety of film stars from the 1930s; similarly, with former Glasgow film projectionist Thomas McGoran’s unique array of donated 35mm film offcuts showing scenes ranging from Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Pluto’s Pantry Pirates (1940) to Westerns and stills from newsreels such as Pathé News, to film company logos and film credit sequences, along with clips from films featuring his favourite star, Deanna Durbin. The suitable display and protection of items such as these, along with their digitisation, were attended to as a priority, and selections from Mr Houlston’s and Mr McGoran’s donations were among the first to appear on the website.

Figure 5: “Picturegoer Postcard Club” Membership Card and Postcard No. P117 –

Jack Buchanan and Joan Barry.

Figure 6 (left): Robert Donat Autograph from 1933 sent to Denis Houlston.

Figure 7 (right): 35mm offcut: Deanna Durbin in Can’t Help Singing (1944).

It has been of crucial importanceto strike a balance between managing the collection for the physical and for the digital archive presented through the CMDA website, Lancaster University’s library catalogue and Lancaster Digital Collections. From a traditional archival perspective, the need to fully survey, index and preserve the physical materials takes precedence, whereas now, within the digital humanities field and for CMDA, the digital aspect and the need for preservation and presentation of the digital materials are the overriding objectives. Although the archiving and display of the material within the Special Collections area needed some consideration, the presentation of the digital materials has been instrumental in informing the overarching approach and structure of the collection. Primarily, it more readily enables, and makes visible, the interconnectedness of the materials, and will also facilitate findings emerging from the QDA process to be fed into the functioning of the search engine. Records and display of the material nevertheless have needed to be adjusted to the specifications of the individual platforms and differentiating between the varying requirements has proved challenging at times. Transparency and consistency, both in view of the system and in detailed documentation of the progress, have therefore been essential in maintaining an overview over the development of the archive.

In terms of physical preservation, with their purpose for the collection in mind and in view of the digital developments outlined above, other types of material also required more considered action. Thanks to intermittent funding from Lancaster University, some of the original interviews recorded on cassette tapes had been duplicated onto CDs in 2004, and the process of converting some of these into digital audio files had already begun in 2017. However, in light of current technological advances in terms of noise filtering and quality, some of this material is now undergoing further re-digitisation. The notion of discarding duplicate CDs and faulty audiocassettes was briefly contemplated and dismissed. Such items form part of the original CCINTB project, providing not only backup and various ways of accessing the material, but also uniquely signal the transition between forms and methods in a single long-lasting research project. Moreover, in view of technical developments, recovery of some of the lost information on audio tapes might even be possible at some future date.

While working through these issues, it has been paramount to keep sight of one of the key objectives for the project, namely to share these materials online using the most appropriate and engaging mechanisms available in order to reach our target audiences. Highlighting the importance of building strong team relationships, the interplay between the experience, various specialisms and expertise of investigators and research associates has enabled in-depth discussions on a variety of topics to keep the project on track, and has proved to be a key strength of the project.

Bringing the CCINTB collection into cultural and academic consciousness, predominantly through creating a digital archive will, we hope, inspire a wide variety of users to reflect on the cultural value of cinema memory and cinema history, and enable substantial new research and pathways for various fields within the humanities and social sciences. With its focus on sharing digital assets, CMDA is firmly located in the field of digital humanities; and looking ahead within our current research environment, digital archives and research tools look certain to increase in prominence. For CMDA and the future of our Collection, this has promising implications, with broad potential for extending the scope of the archive. New contributions to the collection continue to emerge, with one of the core respondents from the 1990s, Thomas McGoran, having recently been interviewed again, sharing yet more memories, experiences and artefacts, including digital versions of his paintings depicting cinema memories. The possibilities for research and digital engagement therefore appear limitless, although, in common with many funded projects, an awareness of time constraints necessarily results in us needing to make concessions and accelerating certain processes that we might otherwise have spent more time on.

One of the challenges still facing CMDA relates to its public engagement outputs and events, and how to effectively advertise the collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. This highlights the particular value and versatility of digital archives and online resources in providing an effective platform to share artefacts and research in both academic and wider cultural contexts. It is hoped that, just as the time differential has proved to be advantageous for the development of the archive due to advances in technology and research, the emerging online developments and innovations could ultimately benefit the CMDA project in reaching a more diverse, global audience than originally anticipated.

CMDA is nevertheless fortunate that we have been able to mitigate the full impact of COVID-19 on the progress of the project through careful planning, numerous detailed online discussions, and by being agile: the relatively small size of the team has enabled us to rapidly change course where it has proved necessary; for example, as the pandemic took hold, work was able to continue remotely in areas such as standardising interview transcripts to an agreed house style and continuing digitisation of the material we had available. At this stage in the project’s lifecycle, the primary disruption has been the lack of access to the physical collection, in order to continue work on the preservation and presentation of the physical archive and the digitising of further material. Yet, we are confident that this valuable work can resume before long and that our Collection will soon be fully available for all to appreciate.

Notes

[1] Extracts from both the CCINTB project proposal and final report can be accessed via the “CCINTB Timeline” area on the CMDA website.

[2] This also includes original work by creative artists in residencies and a theatre production by the Imitating the Dog theatre company, which will draw on the material. Other outreach activities involve collaborations with local communities, archives, museums, cinemas and creative writing workshops. Examples of collaborators include the Glasgow Women’s Library and the British Library’s Save our Sounds project.

[3] The soft launch of Lancaster Digital Collections took place in February 2021, with a wider release planned for later in the year.

[4] A special issue of the Memory Studies journal in 2017 highlights the impact that Kuhn’s work has had on cinemagoing, audience and memory studies (Kuhn, Biltereyst, and Meers).

[5] Accordingly, participants who had previously been collated as part of a group environment, such as in residential homes or local history groups, have each now been given their own accession identifier, whilst still retaining the link to their original reference.

[6] Leaflet is a well-used open-source JavaScript library for interactive maps.

[7] Similarly, the physical archive will also feature a section dedicated to the original project’s framework and research outputs.

[8] The meeting was held at Lancaster University on 22 January 2020 with UK Steering Committee members Martin Barker, Helen Hanson, Emily Keightley and Daniela Treveri Gennari, as well as the CMDA team in attendance.

[9] For example, retaining the use of “cannae” in transcripts of interviews with Glaswegian participants.

[10] The Oral History Metadata Synchronizer is a web application developed by the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History, University of Kentucky Libraries.

[11] The database enables the modelling of relationships between various entities, for example the one-to-many relationship between a “Participants” table and a table storing details about cinemas (that is, one participant has many cinemas they frequent).

[12] Open keyword searches would include searching through hundreds of transcripts, many of which run to over eighty pages.

[13] The CMDA database has been made live on the website since submitting this paper, with the project search engine providing visitors with direct links to document scans and PDF and audio-synced versions of those transcripts that have been standardised. This process is ongoing and will also include the addition of entries for all scannable items of CCINTB memorabilia.

References

1. Can’t Help Singing. Directed by Frank Ryan, Universal Pictures, 1944.

2. “CCINTB Timeline.” Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive. Project website. Lancaster University, 2021, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/cmda/index.php/timeline.

3. Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive. Project website. Lancaster University, 2021, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/cmda.

4. Ercole, Pierluigi, et al. “Cinema Heritage in Europe: Preserving and Sharing Culture by Engaging with Film Exhibition and Audiences.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 11, 2016, pp. 1–12, www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue11/HTML/Editorial.html.

5. “Explore the collection.” The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum. University of Exeter, www.bdcmuseum.org.uk/explore/. Accessed 28 May 2021.

6. Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Reseach.Aldine Publishing Company, 1967.

7. History of Moviegoing, Exhibition and Reception (HOMER). Project Website. HOMERNetwork, 2021, homernetwork.org. Accessed 23 May 2021.

8. Hoyt, Eric. “Curating, Coding, Writing: Expanded Forms of Scholarly Production.” The Arclight Guidebook to Media History and the Digital Humanities, edited by Charles R. Acland and Eric Hoyt, REFRAME/Project Arclight, 2016, pp. 347–73, projectarclight.org/book.

9. Italian Cinema Audiences. Project Website. 2019, italiancinemaaudiences.org. Accessed 23 May 2021.

10. Kuhn, Annette. An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory. I. B. Tauris, 2002.

11. ---. “Heterotopia, Heterochronia: Place and Time in Cinema Memory.” Screen, vol. 45, no. 2, 2004, pp. 106–14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/45.2.106.

12. ---. “Home Is Where We Start from.” Little Madnesses: Winnicott: Transitional Phenomena and Cultural Experience, edited by Annette Kuhn, I.B. Tauris, 2013, pp. 53–63.

13. Kuhn, Annette, Daniel Biltereyst, and Philippe Meers, editors. Memory Studies. Special Issue on Cinemagoing, Film Experience and Memory, vol. 10, no. 1, 2017, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698016670783.

14. Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge UP, 1991.

15. Pantry Pirate. Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Walt Disney Productions, 1940.

16. Papert, Seymour. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. Basic Books Inc., 1980.

17. Reed, Ashley. “Managing an Established Digital Humanities Project: Principles and Practices from the Twentieth Year of the William Blake Archive.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 1, 2014, www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/8/1/000174/000174.html.

18. Řehořová, Irena. “Curating Access, Shaping Cultural Memory: The Czech National Film Archive in the Era of Digitisation.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema, vol. 11, no. 2, 2020, pp. 186–201, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2019.1708044.

19. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Directed by David Hand, William Cottrell, Wilfred Jackson, Larry Morey, Perce Pearce and Ben Sharpsteen. Walt Disney Productions / Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1937.

20. Speed, Maurice F. Movie Cavalcade: The Story of Cinema – Its Stars, Studios, and Producers. Raven Books, 1944.

Suggested Citation

McDowell, Julia, and Annie Nissen. “A Digital Archive Is Born: Revisiting the Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain Collection.” History of Cinemagoing: Archives and Projects Dossier, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 21, 2021, pp. 144–159, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.09

Julia McDowell (PhD) brings over twenty years’ experience as a researcher-practitioner in the fields of TEL and web programming. In her role as Senior Research Associate on the AHRC-funded “Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive” project, Julia’s primary responsibilities are the design and development of the project website, database and search engine, and the creation of audio-synced versions of source interviews. Julia’s research interests include TEL, oral history, digital humanities, and the application of QDA in cinemagoing history and memory studies.

Annie Nissen (PhD) is a Research Associate on the AHRC-funded Cinema Memory and the Digital Archive project. She completed her doctorate at Lancaster University, where she also gained a BA (Hons) in Film Studies and Literature and an MA in Literary and Cultural Studies. Her main area of research lies in Adaptation Studies with a focus on the role of writers and writing within Adaptation practices and in particular early film history. Her responsibility on the CMDA project is to work directly with the archive, organising and cataloguing the collection.