Transnationality and Transitionality: Sandra Kogut’s The Hungarian Passport (2001)

Natália Pinazza

The Hungarian Passport (Um passaporte húngaro) is a coproduction between Brazil, Belgium, Hungary and France. It is directed by Sandra Kogut, a Brazilian artist of Hungarian descent who had previously worked in television and installation art both in Brazil and in France, where she lived for more than a decade, including the period in which she filmed this documentary. A highly experimental and original film, The Hungarian Passport is an account of Kogut’s own endeavour to acquire a Hungarian passport prior to Hungary’s entrance into the European Union. The documentary is composed of footage shot in different places and contains interviews with people ranging from employees of the Brazilian National Archive and Hungarian Embassies in Paris, Budapest and Rio de Janeiro, to family members—in particular her Austrian-born grandmother, Mathilde, to whom the film is dedicated. At the centre of the narrative, Kogut is as a postcolonial, diasporic subject who challenges bureaucratic and rigid notions of identity and exposes how migration laws can be arbitrary and inconsistent in a transnational context.

In the light of recent theoretical debates on postcolonial and diasporic cinema, this article examines how Kogut’s displacement—both as the granddaughter of Jewish refugees and as a foreigner in France—permeates the structure of the documentary in terms of narrative, visual style, characters, subject matter and theme. In the process, it focuses on how the documentary’s fragmented visual and narrative construction uses the journey as a self-reflexive strategy to create a transnational imaginary, thereby interrogating fixed notions of national identity and culture. The documentary addresses issues such as memory and history while contextualising the problems inherent in the process of displacement deriving from prejudice, arbitrariness, and bureaucracy. I argue that this film can be understood within the framework of “accented cinema” established by Hamid Naficy. In An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking, Naficy groups under the term “accented cinema” the work of filmmakers in exile and diaspora who, in general, originate from the world's least developed countries. In a globalised and postcolonial context, these filmmakers have, as Ezra and Rowden point out, acquired “means to insert themselves and their particular experiences of transnational consciousness and mobility into the spaces of cinematic representation and legitimation” (109). This “accented cinema” is not only marked by the foreign accent of the displaced filmmakers and the speech of diegetic characters, but also by the increasingly transnational practices that have transformed the nature of filmmaking. As a coproduction between Brazil and three European countries, made by a Brazilian filmmaker resident in France and entitled to European citizenship, The Hungarian Passport raises questions regarding national status and the cinematic tradition to which it belongs and in which it is received. The film destabilises fixed notions of cultural identity and national cinema while posing metacritical questions to the analysis of transnational films. In this regard, Naficy argues that:

vast global economic and structural changes since World War II have ushered in the postmodern era characterized in part by massive displacement of peoples the world over, creating a veritable "other worlds" of communities living outside of their places of birth and habitus. Transnational filmmakers not only have given expression to these other worlds but also have enriched the cinemas of their home and adopted lands. (“Phobic Spaces and Liminal Panics” 120)

Given her highly fluid identity, Kogut indeed maintains a distinct position within both European and Brazilian film cultures and industries, and thus benefits from ambiguities that enrich her journey, as well as the possibility of reinventing herself. Moreover, she inscribes in the documentary the experience of being in—what Naficy terms—an “interstitial location”, which means to be “located at the intersection of aesthetic systems, languages, nations, practices, cultures” (An Accented Cinema 291). Therefore, the diaspora is considered here not only as a theme inscribed in the film, but also as a component of style. Through the use of self-reflexivity, the documentary engages with its maker’s own interstitiality and features a “double consciousness”, by Naficy’s interpretation, which is acquired from both cinematic traditions in which the documentary is inserted:

This double consciousness constitutes the accented style that not only signifies upon exile and other cinemas but also signifies the condition of exile itself. It signifies upon cinematic traditions by its artisanal and collective modes of production, which undermine the dominant production mode, and by narrative strategies, which subvert that mode’s realistic treatment of time, space and causality. (An Accented Cinema 22)

In another influential study, The Location of Culture, Homi K. Bhabha argues that “the social articulation of difference, from the minority perspective, is a complex, on-going negotiation that seeks to authorise cultural hybridities that emerge in moments of historical transformation” (3). While the post-industrial system appears to be homogenising and centralising, postcolonial subjects benefit from the spaces opened up by globalisation, and thus destabilise fixed notions of centre and periphery by occupying a position both within and outside of European culture. In connection with this, Naficy theorises the existence of exilic and diasporic cinema as “an accented style that encompasses characteristics common to the works of differently situated filmmakers involved in varied decentered social formations and cinematic practices across the globe” (An Accented Cinema 21). For instance, while Kogut’s documentary, in terms of production and theme, is an example of European cinema, it is situated within a Brazilian cinematic tradition by being a coproduction with Brazil and by offering commentary on Brazilian history and society. Documentary is, according to Lúcia Nagib, “a growing genre in contemporary Brazilian Cinema” (xxii) and Kogut is often considered to be one of the most important Brazilian filmmakers of the past decade.[1] Furthermore, in terms of its theme, The Hungarian Passport can be seen as part of a trend in contemporary Latin American cinema that portrays the Jewish community, for example: Argentine films such as Daniel Burman’s “Once trilogy”, Waiting for the Messiah (Esperando al mesías, 2000), Lost Embrace (El abrazo partido, 2003) and Family Law (Derecho de familia, 2006); the internationally acclaimed Uruguayan film Whisky (Pablo Stoll and Juan Pablo Rebella, 2004); and the Brazilian film The Year My Parents Went on Vacation (O ano em que meus pais saíram de férias, Cao Hamburger, 2006).

The Hungarian Passport’s location in and financing by different countries places it within a transnational context where borders, both geographical and metaphorical, are increasingly blurred and where multiple societies and cultures interact with one another. Kogut’s shifting identity creates a sense of simultaneity of place and space, as the distance between Europe and Brazil is shortened by the interplay of the sequences filmed in Paris, Budapest, and Rio de Janeiro. In this respect, Higbee argues that “the kind of films most readily identified with postcolonial cinema deal broadly with the global circulation of peoples and cultural goods in a mediated and interconnected world” (52). Indeed, the documentary engages with stories of Jewish diaspora during the Second World War, as well as offering a comment on the intense wave of migration from Brazil to Europe that has been occurring since the early 1990s. By tackling the reciprocal migration flux between Europe and Brazil, the documentary interrogates, articulates, constructs and de-constructs identities.

There are two marked temporalities in the documentary: the present, which deals with Kogut’s attempts to acquire a passport, and the past, to which her grandmother’s stories belong. However, the distinctions “here”/“there” and “now”/“then” remain in constant flux, and the relationship between Brazilian and European identity is simultaneously defined by both continuity and difference. In this way, the documentary provides a social commentary on both “here” and “there” that constantly shifts from Europe to Brazil and back again, and from “now” (the year 2001) to “then”, induced by her grandmother’s memories of the Second World War. In interweaving and juxtaposing stories of migration from Europe to Brazil with those from Brazil to Europe, the documentary blurs national histories, identities and cultures, thereby challenging recent discourses of European citizenship and its “extra-communitarians”. The ideologies and practices of the European Union, according to Naficy, are instances of creating “actual, material borders and of drawing new discursive boundaries between the self and its others” (An Accented Cinema 219). Such discursive boundaries indeed often apply to “extra-communitarians” who need documents, like visas and work permits, in order to live in the European Union. Naficy defines as “postcolonial ethnic and identity cinema” a cinema dominated by “the exigencies of life here and now in the country in which the filmmaker resides” (An Accented Cinema 15).

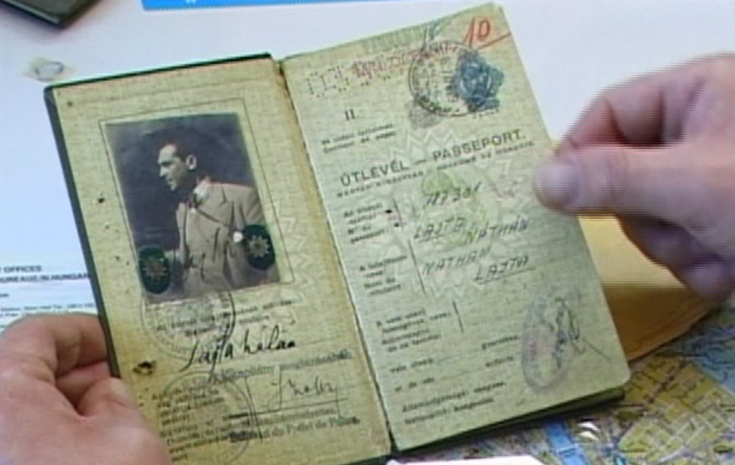

An employee of the Hungarian Embassy in France looks at Kogut’s grandfather’s passport.

In The Hungarian Passport it is clear that the key signifier is the passport, which assumes growing importance for Kogut, for whom it represents a “Europeanness” that is bound up with its status as an official paper combining nationality and mobility. Significantly, in an interview with the website República Pureza, Kogut admitted that “living as a foreigner in France, dealing with many papers, I started to have a daily relationship with it”:[2] which serves to illustrate how, for non-EU citizens who are living in Europe like Kogut, acquiring a (Hungarian) passport is not only a matter of identity, but also an important bureaucratic issue. Although the film shares with European cinema a preoccupation with memory and identity, there is a more practical reason for addressing European identity, and that is the need to acquire an EU passport in order to be able to migrate to Europe. During the 1990s, economic crisis and social problems in Brazil prompted a wave of migration to Europe; thus passports and official papers have become a persistent motif in recent Brazilian films—as is the case in Thomas and Salles’s Foreign Land (Terra estrangeira, 1996), to note but one example. Films like this show how some Brazilian citizens are in search of a new form of identity through claiming their “Europeanness” as a means of leaving their country—which is situated in the margins of capitalism.[3]

Kogut argues that “[i]f I was making a film just because I wanted European citizenship, I think I would not make a film. I just wanted to make the film because it was something complex, because there was not one single reason, but several”.[4] Indeed, Kogut also explores issues such as identity, bureaucracy and anti-Semitism. Perhaps, the acquisition of the Hungarian passport as the prime objective of her journey is questionable, as she does not live or intend to live in Hungary. Moreover, Kogut’s personal motivations to obtain a Hungarian passport are never addressed directly. Although the viewer suspects (and her grandmother suggests at the beginning of the film) that her reasons are linked to the prospect of Hungary’s entrance into the European Union, which occurred three years after the documentary, Kogut opted to keep her motivations obscure. Arguably, this coyness exists in the adoption of a strategy that opposes the logic of the spectacle, which frequently governs contemporary reality shows and other increasingly popular television programmes that expose people’s private lives and thus satisfy a voyeuristic gaze. Consequently, Kogut´s personal matters are much less contemplative than thought-provoking, as they raise issues pertinent to a contemporary history that is marked by immigration and displacement.

It transpires that official documents, letters and assorted papers are key signifiers in the documentary, whether they are scattered about her grandmother Mathilde’s desk or in the National Archive in Rio de Janeiro. The significance of documents and papers is particularly stressed by the sequence in which her uncle recounts how he escaped removal to a concentration camp. As he could not remember his passport number, he guessed a number that, luckily, corresponded to a Portuguese passport. In the film, he holds the piece of paper that saved him and says: “This is my life”. The role of papers as a form of control is also underlined when the employee of the National Archive in Rio de Janeiro says: “Once registered, they [governmental bodies] could kick them [the foreigners] out”. In the film, papers are symbolic of different states of displacement: temporary, as at the end of the film Kogut is granted a document valid for a year that proves her Hungarian citizenship, and permanent, as the “K” stamped on her grandparents´ passports meant that they could not return to Hungary. Moreover, in choosing the administrative process of obtaining a passport as a narrative thread, the film renders visible the meaning of bureaucratic paperwork in life.

Deterritorialising and Reterritorialising Journeys

The growing significance of the passport, both to Kogut and to the narrative, also relates to her postcolonial location. Therefore, the symbolic meaning of acquiring a new passport is linked to Naficy’s argument that while exilic and diasporic films are concerned with being, postcolonial ethnic and identity cinema is concerned with becoming (An Accented Cinema 15). Kogut’s documentary, which was filmed primarily in France (where the filmmaker lived for more than ten years), differs from what is often categorised as postcolonial cinema, such as the work of African émigré directors in France. The main difference is that it does not address issues of the colonial past. Nevertheless, Kogut could be considered an immigrant filmmaker in France, who managed to raise funds both in Europe and Brazil in order to make a documentary that interrogates Eurocentric notions of national identity, history and culture.

In exploring her grandmother’s memories of the Second World War and thereby revealing Europe’s vulnerability, while simultaneously exposing Brazil as the homeland of the European immigrant, Kogut destabilises the articulation of Europe as a fortress. In this context, Kogut enacts and inscribes her interstitial/postcolonial location to expose contradictions—in particular in the arbitrariness of migration laws—and to cross borders both metaphorical and geographical, as the documentary constantly shifts countries, stories and languages. However, being from the so-called Third World does not necessarily mean that Kogut belongs to a marginalised group. In fact, traditional notions of centre and periphery are constantly problematised in the current context of “dispersed hegemonies”.[5] Ella Shohat argues that “[t]hree-worlds theory not only flattens heterogeneities, masks contradictions, and elides differences, but also obscures similarities” (42). Therefore, not all the cinemas that emanate from the “Third World” can be understood within a Third Cinema perspective.

Although the documentary addresses political issues concerning Brazilian history and society, as well as engaging with counter-hegemonic narratives that are expressed both aesthetically and thematically, it does not promote any specific political ideology in the way that Third Cinema does. Naficy argues that “accented cinema is one of the offshoots of the Third Cinema” (An Accented Cinema 30), but points out that the former engages more “with specific individuals, ethnicities, nationalities, and identities, and with the experience of deterritorialization itself” (An Accented Cinema 31), whereas the latter focuses more on the people and the masses.

The Hungarian Passport tackles a public issue, uses non-actors and has a strong reality effect, but it does notembody realistic ethnographic practices nor does it universalise the lives of either Jews in Brazil or Brazilians abroad. Instead, it is characterised by nonlinearity, fragmentation, and a self-reflexive narrative that involves exposing individual experiences and underlining specific power relations and causes that affect the life of the immigrant, such as border control, bureaucracy, prejudice and persecution. Accented filmmakers, according to Naficy, “who live in various modes of transnational otherness inscribe and (re)enact in their films the fears, freedoms, and possibilities of split subjective and multiple identities” (An Accented Cinema 271). In the filmic narrative of The Hungarian Passport, this multiplicity is underscored by ellipses and ruptures that constitute the continuous shifts between places and interviews. Because of Kogut’s travelling identity, the documentary is imbued with images of transitional and transnational places and spaces, including train stations, seaports, vehicles and scenes of people waving goodbye at a platform. The images were collected while Kogut was in transit and they are accompanied by a Jewish folklore soundtrack by Papir Iz Dorkh Vais and Yah Riboh, which thus establishes a nostalgic tone in the narrative. There is a frequent slippage between the footage and the soundtrack, and the experience of displacement is evoked by the interchange between characters’ words and the visual image. The images and the soundtrack are often inserted in the narrative during or after Mathilde’s interviews, working as if they were memory flashbacks. The use of voice-over also connects those images to Mathilde’s narration, creating a sense that those “non-places” (to use Marc Augé’s term),[6] trains and people that feature in the film belong to her story of migration, when actually they are a register of Kogut’s displacement. In this way, Mathilde’s memories work as a leitmotif of Kogut’s own journey, and the juxtaposition of two journeys in the same family challenges material borders and blurs the discursive boundaries between Europe and its “others”.

Footage of Kogut’s journey is used to evoke displacement.

By critically juxtaposing different journeys, the film compares times, places and societies. Whereas Kogut’s grandparents experienced Europe as a place of persecution and war, Kogut’s generation see Europe as a land of promise, and hence Brazil, once the destination of European immigrants, has now became a country of emigrants. This social shift is underscored by the generation gap between Kogut and her grandparents, as their journeys have opposite directions. Moreover, when the officer of the National Archive in Rio de Janeiro points out that many Brazilians are currently seeking European citizenship, the fact that Kogut’s journey is a common one in contemporary Brazilian society is underlined. Therefore, her journey is complex as it involves a quest and search across different countries, and it reveals itself as composite because it interweaves with journeys of other displaced people, both in Latin America and in Europe. Journey and journeying are, according to Naficy, “key features of accented cinema” (An Accented Cinema 222). Additionally, the theme of the journey may also be recognised as situating the documentary within the tradition of European cinema. Wendy Everett argues that European cinema has an “obsession with transition and change, with narratives of migration and the transgression of borders” (62). The tradition of journey, according to Everett,

reflects both the mass movements which have characterised European demographic patterns (particularly, though not uniquely, since the Second World War), and the unstable concepts of geographical boundary and cultural identity which have resulted. (62)

It is precisely this instability of European identity caused by migration flows from Europe to Brazil during the twentieth century that allows a Brazilian citizen to test her “Europeanness” and make a documentary about it. In assessing the extent to which she is Hungarian and the extent to which she is allowed to be one, Kogut exposes contradictions, problems and ambiguities in the bureaucratic practices of the Hungarian embassies in Budapest, Rio de Janeiro and Paris. For instance, the Consul of the Hungarian Embassy in Brazil says that the language test required by the Hungarian Embassy in France was created by the French, while Mathilde tells us how her husband bribed immigrant officials to enter Brazil, thereby revealing how laws can be relative and arbitrary. In her search for a new form of identity, Kogut embarks on deterritorialising and reterritorialising journeys, which involve a process of transformation as she gradually “becomes” Hungarian. The closer she is to acquiring the passport, the more she engages with learning about Hungarian culture and history: for example, by documenting her aunt’s demonstrations of Hungarian cuisine, and interviewing people who talk about Hungarian history. She also learns about the (aforementioned) compulsory language test. However, such deterritorialising and reterritorialising journeys also imply loss. If, on the one hand, displaced people can reinvent themselves and engage with counter-narratives, on the other hand, they may be forced to make choices as immigration laws, along with broader notions of national identity, rely on fixity. In this way, the documentary reveals the difference between the cultures appropriated by Kogut and explores tensions that are triggered by this hybridity. Pertinent to this is Naficy’s insight into the process faced by accented filmmakers:

Freed from old and new, they are “deterritorialized”, yet they continue to be in the grip of both the old and the new, the before and the after. Located in such a slipzone, they can be suffused with hybrid excess, or they may feel deeply deprived and divided, even fragmented. (An Accented Cinema 12)

Assimilations of the new, such as learning to speak the Hungarian language and learning about Hungarian culture and history, can co-exist with Kogut’s “old” identity. However, the issue of assimilation becomes problematic when Kogut questions whether she would have to renounce her Brazilian citizenship in order to obtain the Hungarian passport. Her grandmother, who had previously told the viewer that she had to renounce her Austrian citizenship in order to marry a Hungarian citizen, warns Kogut: “Giving your Brazilian citizenship up is very serious”. Here, Mathilde, who was persecuted in Europe and struggled to acquire Brazilian citizenship, offers an alternative perspective on the Brazilian passport, which is undervalued at the time of the film’s making. Mathilde’s on-screen confessions give the viewer an insight into the discursive boundaries and borders between Brazil and its “other”, in particular because Brazil has historically been the destination of numerous European immigrants. In addition, Mathilde’s perspective challenges Brazilian national narratives. For instance, in revealing the covert anti-Semitism of the Estado Novo and narrating some of her experiences of prejudice in Brazil,[7] Mathilde destabilises Brazilian national discourses around the myth that the country has always been friendly and open to immigrants. Jeffrey Lesser sheds further light on this matter when pointing out that “the insistence that Brazil is a country uniquely free of racism and bigotry, and the realization by ethnic and racial minorities that prohibiting an attitude does not make it disappear, weaves discrimination, or in this case stereotypes of Jews, deeply into Brazilian culture” (67).

Self-reflexivity on Displacement and the Filmmaking Process

This autobiographical and self-reflexive documentary engages with its own status as a postcolonial and diasporic film, by constantly posing questions about its maker’s own “in-betweenness”. In particular, its narrative and style test the viewer’s capacity by divorcing identity from traditional, categorising, political elements, such as the passport and citizenship. In the opening sequence, while speaking on the phone to the Hungarian Embassy, Kogut asks: “Can someone who has a Hungarian grandfather obtain a Hungarian passport?” The sequence in question introduces the complexity of her identity and exposes the inability of bureaucratic services to deal with her case, thereby instigating a self-reflexive dialogue with the audience about the issues raised: if authorities do not know precisely how to respond to her questions, the spectator has little chance of knowing the answer. The variety of languages is another self-reflexive element that plays a very important role in the documentary and its reception, and the different accents and languages within the diegesis reflect the making of the documentary as an international coproduction filmed while the director was in transit. Regarding multilinguality in accented films, Naficy contends that “subtitling is integral to both the making and viewing of these films” (An Accented Cinema 123). In this regard, the connections between the places where The Hungarian Passport was filmed, the nationality of the filmmaker and the people interviewed are destabilised by the dynamics of transcultural contact. The film features English, French, Hungarian and Portuguese dialogue, spoken in a variety of different accents, including Kogut’s accented English and French, her Austrian grandmother’s accented Portuguese, and her Hungarian uncle and aunt’s accented English. Under such circumstances, Naficy argues that the audience of an accented film is forced “to engage in several simultaneous activities of watching, listening, reading, translating, and problem solving” (An Accented Cinema 124). In enacting the problem of language that she dealt with during the making of the film, Kogut poses to the audience the same problem and, thus denaturalises classic narratives by offering a comment on both displacement and making a film about displacement.

Kogut’s highly fluid identity induces a sense of “strangeness” that is further emphasised by the recurrence of the word “weird”—a word that is said throughout the film by different people, including authorities. This strangeness is present in the film on various levels and not least as an aesthetic mode, as Kogut’s previous experience with television and several different genres of film facilitates the use of textual crossovers in her films. In addressing the making of the documentary in 35mm, Kogut states: “I would never have been able to do this film if I had not used a small digital camera. I intend to do other films in 35mm. I am in a crossing of a lot of this and this is as hybrid as the question of nationality. I have always felt very close to people who work in this frontier”.[8] Pertinent to this is Laura Marks’s argument that “hybridity does not simply turn the tables on the colonizing culture: it also puts into question the norms and knowledges of any culture presented as discrete, whole, and separate” (8). Consequently, in registering the effects of its own making, the documentary addresses the process of filmmaking in a transnational context, and also displays the flaws and imperfections that classical narrative attempts to disguise, such as actions that highlight the filmmaking apparatus—like people looking at the camera and on-screen comments about the film.

The film’s fragmented narrative also challenges the objectivity of journalistic interviews and realistic documentary forms, as Kogut does not deny the effects of filming on the people interviewed: “I started to do everything on my own because having three or four people in the location does not allow a more personal approach”.[9] In fact, her intervention changes the course of the narrative by emphasising the effect that the act of observing has on the person who is under observation. For instance, the interviews with Mathilde while she is eating and with Kogut’s relatives in Budapest take the form of conversation, due to the closeness of the relationship between them. As a result, family affection highlights the stark contrast between the private sphere and impersonal public places. It is clear that the shots of the endless corridors of embassies and shelves full of documents in the National Archives suggest that individual stories of loss and displacement are transformed into mere numbers. In specifying and situating displacement, the film’s emotional power is enhanced, as Consuelo Lins puts it: “it is a film in which family memory becomes immediately a world-memory” (76).[10] Mathilde’s interviews offer lucid accounts of her experience of migration to flee Jewish persecution during the Second World War, establishing an emotional tone to the documentary. The fact that different people across the globe can identify with the issues raised by the narrative renders its reception complex. Although the film engages with stories of the Jewish diaspora and, thus, has been included in the programme of many Jewish film festivals—including the New York Jewish Film Festival—the documentary does not address solely this specific community. Interestingly, despite being a coproduction, along with being filmed in different places, the film more often than not was categorised as a Brazilian film in the programme of many film festivals—such as Le Festival du Cinéma Brésilien de Paris. Therefore, it seems that the categorisation of the documentary in some film festivals has relied primarily upon Kogut’s place of birth. Nevertheless, Kogut’s interstitial location and postcolonial subjectivity has had some impact on the reception of her films. For instance, on the website of the AWFJ (Alliance of Women Film Journalists), Maitland McDonagh refers to Kogut as “a citizen of the world”, given her several displacements: “Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1965, Kogut grew up in Brazil, spent more than a decade in France and now lives in the United States” (n. page).

Naficy argues that “accented filmmakers are not just textual structures or fictions within their films; they also are empirical subjects” (An Accented Cinema 4). Indeed, there is a slippage between identity and performance of identity that renders the narrative multivocal, as Kogut occupies both inside and outside positions or, as Naficy puts it, “the intersubjective and interstitial spaces that are characteristic of accented cinema” (An Accented Cinema 72). The Hungarian Passport is constructed by the interweaving of interviews, and unexpected interactions reflect its very process of production. Kogut performs multiple functions in the documentary. Not only did she raise funds to direct the documentary, she also functions as a subject. Despite not appearing in the film, her voice is heard off-screen and her presence is often felt through point-of-view shots, establishing a self-reflexive interweaving of Kogut’s own person and persona in the diegesis. Kogut’s involvement in the documentary also reflects “the multiplication or accumulation of labor, particularly on behalf of the director” (Naficy, An Accented Cinema 48), which is the key characteristic of what Naficy refers to as the “interstitial mode of production”. Furthermore, one of the key characteristics of the accented film, according to Naficy, is convolution:

funding sources, languages used on the set and on screen, nationalities of crew and cast, and the functions that filmmakers perform are all multiple … This complexity includes the artisanal conditions and the political constraints under which the films are shot. (An Accented Cinema 51)

As the documentary is a registration of Kogut’s attempt to acquire the passport, the obstacles imposed on her bureaucratic endeavour also undermine the film’s closure. That is, the uncertainty involved in obtaining the passport and concluding the film suggests that filmmaking itself is a journey that poses complex, open-ended questions. In this respect, one of the people interviewed at the beginning of the film addresses self-reflexivity of the documentary humorously: “And if obtaining that nationality is a long-term undertaking if not an impossible one, you can count on rolling film for years”. Furthermore, regarding the lack of closure, the documentary poses questions without giving answers, perhaps because there is not yet an official solution to the increase in the number of people who are on the move, like Kogut. The documentary encourages spectatorial questions, in particular that of whether or not Kogut got her passport: the absence of a definitive answer undermines the resolution of both her documentary and her quest, and stresses that identity formation is an open and indeterminate process.

Concluding Comments

Kogut's autobiographical documentary narrativises the dynamics of displacement through the diegetic staging of bureaucratic mechanisms of fixing identity and constraining mobility while creating a visual imaginary that promotes fluidity in the process of identity formation. The transnational imaginary space created by the documentary exposes the rigidity of national frameworks by showing how they fail to explain the connections between the multiple national, cultural and historical contexts presented in the narrative. Consequently, films like The Hungarian Passport have the potential to reveal both the diasporic and postcolonial experience, and the national as a privileged site in which cultural identity is conceived. Moreover, through the exploration of issues such as identity, history, prejudice and diaspora, the film reveals the limitations of creating an identity founded on national and historical bases, and attempts to move beyond them. By so doing, the documentary engages with existing debate regarding the process by which identity is constructed through socio-political affiliations and culture and, thus, disrupts the discourses that separate European identity from its “others”.

Notes

1. Kogut is best known for her experimental work, doing video and installation art. She also directed Mutum (2007), which closed the Directors’ Fortnight program in Cannes in 2007.

2. Translated from Portuguese: “Vivendo como estrangeira na França, lidando muito com papelada, eu comecei a ter uma relação cotidiana com isso” (author’s own translation).

3. Perhaps, the notion of Brazil being in the margins of capitalism is increasingly questionable in a multipolar world order, where new economies are emerging. Nevertheless, Kogut belongs to a generation that experienced Brazil as a country of economic and politic crisis.

4. Translated from Portuguese: “Se eu tivesse pedindo um passaporte apenas porque queria uma cidadania européia, acho que não faria um filme. Só quis fazer o filme porque era uma coisa complexa, porque não havia um so motivo - eram vários)” (author’s own translation).

5. See Appadurai, “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy” (1990).

6. See Augé, Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (1995).

7. Estado Novo, literally translated as “New State”, refers to a dictatorial period in Brazil during the rule of President Getúlio Vargas between 1937 and 1945.

8. Translated from Portuguese: “Eu jamais conseguiria fazer esse filme se não tivesse usado uma câmera pequena e digital. Pretendo fazer outros filmes em 35mm. Estou num cruzamento de um monte de coisas e isso é tão híbrido quanto a questão da nacionalidade. Eu sempre me senti muito próxima de pessoas que trabalham nessa fronteira” (author’s own translation).

9. Translated from Portuguese: “[...] passei a fazer tudo sozinha, porque para conseguir uma relação pessoal com alguém não dá para chegar lá com três ou quatro pessoas” (author’s own translation).

10. Translated from Portuguese: “É um filme em que a memória de uma família torna-se de imediato uma memória-mundo” (author’s own translation).

References

1. Appadurai, Arjun. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy”. Public Culture 2: 2 (1990):1-24. Print.

2. Augé, Marc. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso, 1995. Print.

3. Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. Print.

4. Everett, Wendy, ed. The Seeing Century: Film, Vision, and Identity. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, 2000. Print.

5. Ezra, Elizabeth and Rowden, Terry. “Motion Pictures: Film, Migration, and Diaspora”. Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader. Ed.s Ezra and Rowden. London: Routledge, 2006. 109-110. Print.

6. Family Law [Derecho de familia]. Dir. Daniel Burman. BD Cine, Classic Film, and Instituto Nacional de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales (INCAA), 2006. DVD.

7. Foreign Land [Terra estrangeira]. Dir. Daniela Thomas and Walter Salles. VideoFilmes, 1996. DVD.

8. Higbee, Will. “Locating the Postcolonial in Transnational Cinema: The Place of Algerian Émigré Directors in Contemporary French Film”. Modern & Contemporary France 15:1 (2007): 51-64. Print.

9. Lesser, Jeff. “Jewish Brazilians or Brazilian Jews: A Reflection on Brazilian Ethnicity”. Shofar 19:3 (2001): 65-72. Print.

10. Lins, Consuelo. “Um Passaporte Húngaro, de Sandra Kogut: Cinema Político e Intimidade”. Galáxia 4:7 (2004): 74-85. Print.

11. Lost Embrace [El abrazo partido]. Dir. Daniel Burman. Instituto Nacional de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales (INCAA) and BD Cine, 2003. DVD.

12. Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses. London: Duke University Press, 2000. Print.

13. McDonagh, Maitland. “Women on Film - Global Lens Filmmaker Sandra Kogut”. Alliance of Women Film Journalist, 24 January 2009. Web. 03 October 2010. <http://awfj.org/2009/01/24/women-on-film-global-lens-filmmaker-sandra-kogut-maitland-mcdonagh-interviews/>.

14. Mutum. Dir. Sandra Kogut. Ravina Filmes and Gloria Films, 2007. DVD

15. Naficy, Hamid. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001. Print.

16. ---. “Phobic Spaces and Liminal Panics: Independent Transnational Film Genre”. Global/Local: Cultural Production and the Transnational Imaginary. Eds. Rob Wilson and Wimal Dissanayake. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1996. 119-144. Print.

17. Shohat, Ella. “Post-Third-Worldist Culture: Gender, Nation and The Cinema”. Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader. Ed.s Elizabeth Ezra and Terry Rowden. London: Routledge, 2006. 39-56. Print.

18. The Hungarian Passport [Um passaporte húngaro]. Dir Sandra Kogut. Radio Télévision Belge Francophone (RTBF), Zeugma Films and VideoFilmes, 2001. DVD.

19. The Year My Parents Went on Vacation [O ano em que meus pais saíram de férias]. Dir. Cão Hamburger. Gullane Filmes, Caos Produções Cinematográficas, Miravista, Globo Filmes and Petrobrás, 2006. DVD.

20. "Um Passaporte Hungáro—Entrevista". República Pureza. Web. 9 Oct. 2010. <http://www.republicapureza.com.br/index.php?option=com_content&viw=article&id=48&Itemid=55>.

21. Waiting for the Messiah [Esperando al mesías].Dir. Daniel Burman. Astrolabio Producciones S.L and BD Cine, 2000. DVD.

22. Whisky. Dir. Pablo Stoll and Juan Pablo Rebella. MK2 Diffusion, 2004. DVD.

Suggested Citation

Pinazza, N. (2011) 'Transnationality and transitionality: Sandra Kogut’s The Hungarian Passport (2001)', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 1, pp. 8–20. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.1.02.

Natália Pinazza is currently completing her PhD on globalisation and identity construction in contemporary Argentine and Brazilian cinema at University of Bath, United Kingdom. She graduated in Languages and Literature from University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, and joined University of Bath in 2007 to do an MA at the Department of European Studies and Modern Languages. Her main interests cover postcolonialism, globalisation, and cultural policy.