Egyptian Film Censorship: Safeguarding Society, Upholding Taboos

Dina Mansour

Introduction

Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003) caused controversy in the Western world, with the Catholic Church calling the contents of the book “shameful and unfounded lies” (“Church Fights Da Vinci Novel”). Surprisingly, given that they deal with a non-Islamic religion, both the book and the film (The Da Vinci Code, Ron Howard, 2006) were faced with an immediate ban across countries of the Arab and Muslim regions—including in Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iran and Lebanon—because, as the Secretary General of the Jordanian Council of Churches, Archbishop Hanna Nour, explained, “[it] harms Christian and Muslim religious symbols by calling into question what is written in the Gospels and the Koran on the personality of Christ” (qtd. in Pereli). In fact, in the Arab and Muslim worlds, the very issue of religion is considered taboo. The Da Vinci Code, like many other foreign as well as locally produced films, represents the constant clash between art and culture characterising Arab societies that are profoundly influenced by cultural and religious traditions. Locally produced Arabic films like Dunia (2005), The Yacoubian Building (Imaret Yacoubian, 2006) and Cairo Exit (Al-Khoroug, 2009) are examples of films that touch upon what are considered to be culturally sensitive topics and taboos, which are said to “harm public morality” and “misrepresent the tradition and culture of Arab societies” (Hegab, 1987, 5–7). Although such films gained international recognition and were well received in the West as truthful depictions of specific cultural and social realities, they were often deemed morally inappropriate by censorship bodies in the Arab world. Like domestic films, imported films are also subject to censorship and are often cut and modified to fit with what is deemed to be culturally, morally and religiously appropriate.

With the advent of globalisation, and with the mass influx of film production coming from all over the world, censorship in the Arab region has become a tool to balance cultural relativism. Acting as a cultural mirror, film has always been closely connected with societies’ cultural identity—representing, reflecting, criticising and even stirring them towards change (Hegab 5–7). Yet, in societies that are inherently traditional and patriarchal, censorship has been used to shield society from any emerging or incoming moral norms, traditions or values that contradict the existing religious and cultural values of Arab societies—thus acting as a guard between art and culture. Censorship, on the other hand, imposed taboos that have stood in the way of accurately reflecting and mirroring existing societal and cultural problems in Arab societies and many Arab actors and filmmakers, most notably Omar Sharif and Youssef Chahine, claim that it has harmed the industry and severely limited creativity (Curry; Andary 96). It has, moreover, promoted conservatism and pushed society to live in denial and dismiss the existence of societal problems as those represented in Dunia or Cairo Exit and even oppose their portrayal. This may partly explain the trend towards commercial, profit-oriented films that started in the late 1990s in Egypt with the extraordinary success of Ismailia Back and Forth (Isamailia Rayeh Gayy, 1997); these films, however, are criticised for their superficiality and for seeking only to entertain through comedy.

Cairo Exit (Hessam Issawi, 2009, Film House Egypt).

This essay aims to analyse the role of censorship in the context of the relationship between Arab cinema and culture—a relationship often overlooked and perhaps intentionally ignored—and will focus on the case of Egypt. The Egyptian film industry being the biggest in the Arab world in terms of volume of production and popularity, it was once labelled as the “Hollywood of the Arab world”. [1] In particular, this essay aims to examine how censorship not only limits creativity and art but, moreover, hinders the true reflection of cultural identity by forcing the portrayal of a particular image of culture and society. [2] In so doing, it will examine how censorship has always been used as a tool (whether by colonial powers or the state) to control the representation of existing social and cultural realities and is even used to define cultural and religious norms in the society, thus also indirectly affecting the existing normative context. It is particularly important to reflect on this role of censorship, especially with the rise of political Islam to power as a result of the Arab Spring revolutions and the fear that the Egyptian film industry in particular will be directed according to a new, more restrictive definition of what is deemed art and what is regarded as taboo.

Arab Cinema and Cultural Identity: The Struggle to Represent the National Culture

Film relies on precise social, political and cultural contexts to reflect and mirror contemporary moral values, norms and attitudes while dramatising existing societal problems. The relationship between film and culture is portrayed rather vividly in traditional societies of the Arab world that aim to safeguard themselves from the inflow or emergence of cultural norms and values that are either deemed inappropriate or defy shared norms. Little attention has been paid in literature, however, to the subject of cultural identity and Arab cinema. Viola Shafik’s Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity is one of the very few contributions that thoroughly contextualises Arab cinema and cultural identity employing a critical approach that takes Western film theory into account (2). As a medium initially invented in the West, the art of filmmaking has been constantly evolving with the development of the Western world, especially in terms of the technical and artistic advancement of the medium (4). Throughout its history, the Arab world, on the other hand, has been struggling with the dilemma of being able to represent its own cultural identity due to a long era of colonisation followed by an era of formal restriction on freedom of expression and creativity under state censorship. Under colonisation, countries of the Arab world were represented as exotic lands by foreign filmmakers, who misrepresented the domestic cultures by portraying stereotypical perceptions of the Orient. The representation of the Other was nothing but mere surface depiction. According to Guy Hennebelle:

Cinematic production in the Arab world … has been held back by the traumatic effects of colonialism. One of the most lasting and pernicious results of colonialism was a rejection of Arab culture by the intellectuals. They became convinced that only an imitation of the culture of the colonizers would overcome national decline and backwardness. The result was a shallow and imitative cultural production. (4)

At the end of the nineteenth century, with the invention of the cinema in the West, almost all Arab countries were either under direct Western (mainly British, French and Italian) occupation or under a mandate system. Colonisation, nonetheless, helped in transferring the new invention to the Arab world, and especially to Egypt. As in much of Egypt’s history, its geographical location between the East and West gave it political importance within the region, thus making it into a meeting point and melting pot, and a gateway for all the latest inventions coming from Europe, including film. Within the Arab region, Egyptian cinema has long been dominant—not only in terms of artistic merit, but in being the first to represent its national culture. Colonisation, however, also prevented the rest of the Arab nations from representing themselves or reflecting the Arab social reality and culture by means of cinema until the mid-twentieth century, when Arab countries gained their independence (Shafik 18). In fact, even though the art of filmmaking reached Egypt as early as 1896, only a few months after the first film was screened in Europe, it took Egypt another thirty years to see its culture reflected on the screen (10).

With the development of filmmaking in the Arab region, censorship began to be imposed in the early years of the twentieth century, initially not only to guard public norms, morals and religion, but also to control the display of any political ideas aimed at criticising foreigners or inciting any resistance against monarchs or colonisers (Ali 84). It was even said that, when Egyptians started to take control of their film industry and produce films that represented Egyptian culture, Egyptian films were censored and even banned throughout the African French colonies (Shafik 15–6; Georg 33). Film censorship in Egypt, which was officially instituted in 1914 by the Palace and the English Embassy, while being administered by the Ministry of the Interior, was not entirely aimed at maintaining public norms and values, but was justified as a military and political necessity regarding matters of national security, which is why it was first administered by the Ministry of Interior. This continued until the establishment of the Ministry of Social Affairs in 1938, which took over this role and added “safeguarding social order and public morals” to its aims (Mumtāz 31). During this period, and as in the rest of the region under colonisation, censorship in Egypt obliged directors to refrain from portraying any kind of criticism of foreigners, government officials, state authority, religious institutions or the monarchical government (even monarchical governments of other countries from the past or present, for fear of analogies with the contemporary regime) and went as far as prohibiting any cinematic representation of conflicts between peasants and landowners or the portrayal of any nationalist or socialist ideas, past or present (Shohat 24). This hindered the development of Arab cinema and prevented its depiction of social and political events and changes. In fact, according to Shafik, this has even affected the perception of the medium of film in the region, where, in spite of a seventy-year history, “because its existence is based on a Western technique, Arab cinema is frequently criticized as evidence of Westernisation and acculturation” (4).

After initially being introduced into the most elevated strata of society, Arab cinema in general and Egyptian cinema in particular went hand in hand with the rise of the urban bourgeoisie, which used it as a means of class expression and popular entertainment that shaped the general consciousness of the urban population (Shafik 122; Shohat 24–5). This was a trend that started in the first two decades of the twentieth century and continued until the Nasser regime (Samak 1). Quassai Samak contends:

This new artistic form was to become one of the means by which the bourgeoisie expressed its ambitions and aspirations. Cinema also became a major economic investment of the bourgeoisie and an important tool to perpetuate its control and cultural domination over the people in general and the urban population in particular. (1)

Ismailia Back and Forth (Kareem Diaa El-Din, 1997, Hassam Ibrahim & Co.).

With the 1952 Egyptian Revolution, the dominant ideology was an anti-colonialist one. Gamal Abdel-Nasser’s regime marked a turn away from Western domination and a resurgence of a nationalist Arab culture. Though the revolution did not produce a complete transformation, it came to energise cultural life with cinema becoming the main tool to promote the new nationalist spirit and an important part of the initial stages of nation building. Under Nasser, cinema transformed itself to reach all strata of society—especially the lowest social classes, peasants and farmers—and to reflect the national culture more faithfully. It moreover turned into a tool of the state aimed at conveying a nationalist ideology, which provided the people with an interpretation of reality that claimed to transform them into active citizens as well as promote solidarity and a new solidified cultural identity among the masses (Shohat 27). Overt political censorship, however, especially towards any direct criticism of political leadership, as well as censorship on religious themes, has since become the norm. This trend also progressively impelled filmmakers and producers to circumvent restrictions in various ways, such as producing two versions of the same film (one for the domestic market and another for export) or resorting to the use of various forms of antiphrasis or ambiguities as well as self-censorship (Shafik 35–6; Sabry). [3] Yet, as Egyptian cinema faced a severe financial crisis in the late 1990s, it was left with no other choice but to renovate and reinvent itself. The unexpected, yet enormous, success of the relatively low-budget comedy Ismailia Back and Forth was the starting point of a new trend in the industry that dissuaded the cinema from directly reflecting or criticising societal and cultural realities, and rather encouraged it to mock the deteriorating societal, economic and political situation through comedy (Sabry). Such films soon pushed the general preference towards the mass production of profit-oriented comedies that slowly lost touch with the existing socio-political context. With The Yacoubian Building in 2006, Egyptian cinema started again to see a trend aimed at providing direct social critique of existing realities in the society while defying taboos. The Yacoubian Building had all the ingredients for success: a huge budget, a strong international marketing campaign and an international best-selling novel of the same title by Alaa Al-Aswany on which it was based. All this contributed to the instant inclusion of The Yacoubian Building in the canon of world cinema and, with it, to the introduction of a new trend of cinematic representation of the national culture (Sabry). Though the film came to offer a critique of the degraded living standards of the poor and to visibly portray the degradation of social makeup after the 1952 Revolution, it was criticised for doing so through a Western lens and for employing Western artistic techniques in portraying the national context. In fact, as argued by Kholeif, the film seemed to aspire “to its Franco-European influence, and in a sense elevates itself from culturally specific Egyptian popularism” (Kholeif 4). This could be seen in the film’s highlighting of the European architecture and fashion of the early twentieth century in Egypt and the European traditions and customs adopted at that time by Egyptian society—especially by the bourgeoisie. Moreover, songs by French singer Edith Piaf could be heard throughout the film, with the character of Franco-Egyptian lounge singer Christine singing renditions of “La Vie en Rose” as well as other Western songs (11).

The Yacoubian Building was followed by films such as Waiting for Better Times (Heen Maysara, 2007), Chaos, This Is (Heya Fawda, 2007), White Ibrahim (Ibrahim Al-Abyad, 2009) and Shehata’s Store (Dokan Shehata, 2009), which opened the door to a trend that provided a raw representation of poverty, state corruption and life in the slums of Cairo, thus introducing a bottom-up approach to mirroring and representing Egyptian society in film.

State Censorship: A Patriarchal Guard on Art and Morality

The Arab cinemas are both the product and the expression of a long and unresolved struggle for the control of the image, for the power to define identity. That identity is clearly rooted in the crossroads of culture of the region, extending as it does between Europe and Black Africa, between the Atlantic and the Arabian Gulf, but also between the city and countryside and desert ... between a colonial past and a nominally independent present. (Miriam Rosen qtd. in Salem 1)

The above quote by film critic Miriam Rosen reflects the current reality governing the relationship between Arab cinema and cultural identity. When it comes to evaluating the role of censorship in the Arab world, it can be said that it acts as the patriarchal hand of the state that determines what is allowed to be shown to the public, thus maintaining a precarious balance between what is deemed to be art and what is considered obscene or morally inappropriate—an evaluation that is highly subjective and context-based. According to a 1976 Egyptian law on censorship:

“Heavenly” religions [i.e. Islam, Christianity, and Judaism] should not be criticized. Heresy and magic should not be positively portrayed. Immoral actions and vices are not to be justified and must be punished. Images of naked human bodies or the inordinate emphasis on individual erotic parts, the representation of sexually arousing scenes, and scenes of alcohol consumption and drug use are not allowed. Also prohibited is the use of obscene and indecent speech. The sanctity of marriage, family values, and one’s parents must be respected. Beside the prohibition on the excessive use of horror and violence, or inciting their imitation, it is forbidden to represent social problems as hopeless, to upset the mind, or to divide religions, classes, and national unity. (qtd. in Shafik 34) [4]

In addition to the fact that the above-stated prohibitions prevent the accurate portrayal of real-life events and oblige filmmakers to observe regulations that are left open to interpretation, in a country like Egypt censorship is moreover always left to the discretion of censors (Goerg 29). At the same time, regardless of whether the film is a true depiction of the existing societal, cultural or political context, there always are red lines that cannot be crossed in Arab countries based on codes that differ from one country to the next. Locally produced films in Egypt, especially in the last few years, have taken great strides in social critique and in mirroring social problems, especially those relating to the lives of the poor, life in the slums, the violation of the rights of women, government corruption, social problems relating to the conservative cultural norms and traditions, Islamic fundamentalism, interfaith relationships and homosexuality. In reflecting and depicting culture, however, cinema and art in general often clash with the taboos set by censorship bodies—whether they are taboos that relate to moral or religious values or even political taboos. Yet, there always are exceptions and it is often unknown why exceptions are made. In fact, while The Yacoubian Building contained explicit references to sexuality and homosexuality, police torture, government corruption and terrorism, it was passed by the censors without any cuts. Prior to its release, 112 Members of Parliament demanded that scenes dealing with issues that touch upon public morals and traditions be cut, particularly those dealing with homosexuality, claiming that the film defamed Egypt and promoted the spread of “obscenity and debauchery” (“Egypt debates controversial film”). Despite the campaign, the film was left uncut thereby violating all existing religious and cultural taboos and achieving groundbreaking box-office returns locally and international recognition and praise in the West (“Taboo-smashing film breaks Egypt records”).

Conversely, Cairo Exit was stopped by censors before its release despite dealing with issues that are as real and urgent as those depicted in The Yacoubian Building. Cairo Exit deals with the issue of interfaith and premarital relationships while portraying the brute reality of living in poverty in the poorer suburbs of Cairo, thus bringing to life cultural realities that are rarely touched upon or even acknowledged. The main characters in the film are torn between existing cultural and religious taboos and a life in poverty—all motivated by the same goal: escaping those realities and exiting Cairo. Centring on the poor suburb of Dar El-Salam, an area in the outskirts of Cairo whose inhabitants are mostly lower and working class, the film portrays the relationship between an 18-year-old Coptic girl, Amal Iskander, and her Muslim boyfriend Tarek. First screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, the film’s uncompromising portrayal of social realities was deemed by censorship bodies in Egypt to be morally inappropriate, and to represent inherently modern Western values and traditions that are not germane to the Egyptian cultural context. Interfaith relationships are considered to be an ultra-sensitive, taboo issue and are usually not passed by the Egyptian censors despite their existence in society. In fact, the mere portrayal of the life of an ordinary Christian family living in Egypt during the 1960s in the 2004 film I Love Cinema (Baheb El-Cima), which was Egypt’s submission for Best Foreign Language Film to the 77th Academy Awards, faced a campaign requesting its banning by Egyptian Christian clerics and resulted in mass protests of Copts and Muslims on the streets of Cairo. This was in addition to a lawsuit citing the film as “displaying a lack of respect for the [Christian] religion, and its places of worship” and blaming “the minister of culture, and then the minister of interior, for allowing the movie to be released” (El-Rashidi, “Cinema case unresolved”). This is reflective not only of the fact that censorship regards the issue of religion as taboo, but also that the general public regards any mention or (mis)representation of religion as being an untouchable topic.

I Love Cinema (Osama & Hany Girgis Fawzy, 2004, Al-Sobky Video Film).

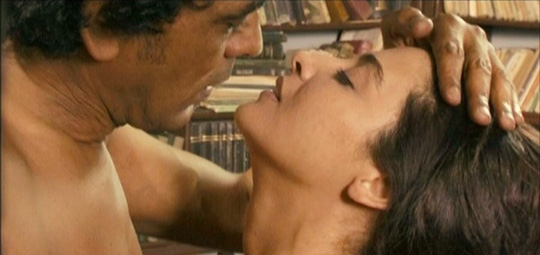

Moreover, the bureaucratic procedure imposed by censorship bodies in Egypt requires a strict process of red tape and paperwork that is sometimes made even more complicated by corruption, which has also created bureaucratic and legal loopholes that have resulted in the banning of films (Madkour). Dunia falls under the category of films that were banned due to failing to fulfil the bureaucratic requirements imposed by state censorship to permit the release of films. In what is considered to be an unprecedented incident in the history of Egyptian cinema, Dunia, a film written and directed by Lebanese filmmaker Jocelyne Saab, was banned from screening in cinemas in Egypt after it was widely advertised to be released in at least seventeen cinemas nationwide (Farid). Officially the film was banned for the director’s failure to pay 120,000 EGP (equivalent to around 15,000 Euros) in fees due to three syndicates, namely the cineastes’, actors’ and musicians’ syndicates, without which the Censorship Bureau cannot grant screening permission to any film. These fees are decided on a case-by-case basis and are left to the discretion of the Censorship Bureau. The filmmakers of Dunia, journalists and critics alike believe that the real reason why itwas banned was its taboo topic (El-Sherbini; Purtill). Dunia deals with the issue of forced genital mutilation/circumcision (FGM/C) in Egypt and its effects on the life of the lead character, Dunia. Though FGM/C is originally an African tradition and Islamic clerics have affirmed it to be so, it is widely practiced in Egypt—especially among the lower and poor classes—as well as across the Arab region. The film portrays the effects of this cultural practice on the life of a grown woman and how circumcision transcends the physical and is symbolic of the mental and psychological restriction that is imposed by society on the life of women in the name of culture and traditions.

Dunia (Jocelyn Saab, 2006, Catherine Dussart Productions).

The relationship between cinema and culture is shaped by the decision of the censorship bodies as to what is culturally acceptable to the public, and which existing social and cultural norms can be shown and which cannot for fear of spreading obscenity or debauchery. While cinema endeavours to mirror and bring to life our evolving cultural and social contexts, censorship, on the other hand, represents the patriarchal guard that hinders its true reflection. This is especially true when laws are vague and open to interpretation and censors are given full discretion to cut or ban films according to their own cultural interpretation.

Film and Public Reaction

The Arab cinema has for too long delighted in dealing with subjects having no connection to reality or dealing with it in a superficial manner. Based on stereotypes, this approach has created detestable habits among the Arab viewers for whom the cinema has become a kind of opium. It has led the public away from the real problems, dimming its lucidity and conscience. At times throughout the history of Arab cinema, of course, there have been serious attempts to express the reality of our world and its problematic, but they have been rapidly smothered by the supporters of reaction who fought ferociously against any emergence of a new cinema. (The Palestinian Cinema Group Manifesto qtd. in Hennebelle 7–8)

The last decade, as already mentioned, has witnessed a rise in commercial comedies welcomed by audiences both in Egypt and across the region. The public has been enthusiastically receiving light-hearted comedies, usually dealing with such themes as clichéd love triangles, claiming that such films help them forget their daily problems and give them relief. This market demand has created a major change in the genre of the majority of films produced in Egypt. Overwhelmed by poverty and a feeling of helplessness, the general public has resorted to cinema for relief and to enable them to cope with their often grim reality. Instead of demanding films that reflect the evolution of the socio-political and cultural context, the market has pushed Egyptian cinema far away from reality and has opened the door to an era of commercialism and escapism. At the same time, the reaction of the public to films that offer a rather raw representation of reality and of the lives of the poorest in Egypt is often extreme, claiming that such portrayals defame Egypt’s image. The 2009 film, Shehata’s Store, has faced three Hesba cases during its production, demanding the Censorship Bureau to ban it from release and accusing director Khalid Youssef of defaming Egypt. [5] The reaction of the public also took its toll on Dunia; many prominent Egyptian actresses in fact turned down the title role of Dunia for fear of public reaction and even condemnation and boycotting (Al-Sherbini). Hannan Turk, who accepted the role, was heavily attacked by the general public and the local media and, even though she publicly announced that her role in Dunia would be her last without the Islamic veil, her faith has been openly questioned resulting in an invasion of her privacy. Talking about her film, Saab has rightly noted on this emerging public attitude towards films in Arab societies that “[s]ociety should not bury its head in the sand and should deal with sensitive issues frankly and honestly” (Al-Sherbini).

A close examination of the reaction of the public to films that they consider defamatory or offensive to religion, public norms and morals shows the extent to which the public in Egypt today (and increasingly after the rise of political Islam to power) and across the region relies on and even calls for censorship in maintaining a close patriarchal guard on morality. Instead of calling for freedom of expression and creativity, the general public usually blames censorship bodies whenever a film is released (whether local or Western) that is seen to spoil the minds of the young generations, spread obscenity or defame religion or the country’s image. The question, however, is whether the long trend of censorship has directly contributed to this reaction from a public that for so long has been accustomed to receiving filtered art and a redefined culture.

Foreign Films: Balancing Cultural Relativism

As The Devil’s Advocate (Taylor Hackford, 1997) hit theatres in Egypt in 1997 not only was it surprising that such a controversial film would be released, but more importantly that the film’s final scene, in which the main character played by Al Pacino criticises and insults God, would be left uncut. In fact, in Egyptian cinemas, the very mention of God would ordinarily ensure that the ensuing dialogue would be omitted from the film. When The Devil’s Advocate was first released, instead, the whole final dialogue was uncut while the Arabic subtitles were completely removed. This was a censorship decision that clearly aimed at differentiating between two kinds of audiences in cinemas: those who speak and understand English (and, by proxy, would have a better understanding of Western culture) and those less educated who would thus be shielded from dialogue that, according to Egyptian censorship bodies, is offensive to God. Despite this tactical move, the film caused a stir in the local media and was soon banned.

Imported films do not escape censorship and their content is scrutinised with reference to the spheres of religion, morality and politics. Despite the fact that these films are produced abroad and are thus reflective of a more open cultural and socio-political context, many films never reach Arab audiences. Censors in Egypt usually demand viewing copies of films intended for distribution in order to consider their suitability for domestic release. It is then common for the censors to request the cutting of certain scenes or dialogue or, in extreme cases, to outright refuse release. Censorship discretion is apparent in such decisions, a discretion that is usually based on the subjective evaluation and understanding by censors of the general context of the film (Mumtāz). Such subjective evaluation is sometimes hampered by the censors’ lack of understanding of the foreign culture that the film deals with as well as of the original language of the film. This in turn often results in excessive cutting that in some cases leaves Egyptian audiences unable to understand what they missed out upon while blurring the aims of the film. By cutting scenes and dialogue, censors aim to modify the contents of the film to fit with the moral context of the receiving audience, despite the fact that the film stems from and is reflective of another value system and cultural context. Such patriarchal methods aimed at separating art and morality prevent audiences from being exposed to a culture other than their own and strip films of their cultural contexts.

Even though Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code was released in Egypt, the film based on it was banned for calling into question the life of Jesus Christ and, thus, for defaming Christianity. The Da Vinci Code is just one example of a film that was met with a complete ban. The animation The Prince of Egypt (Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner and Simon Wells, 1998), which tells the story of Moses as he delivers his people out of Egypt, was also banned in Egypt, due to the fact that the film depicted and impersonated a prophet, which is against Islamic teachings. Yet, the same rule was not applied when Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was released across the region, with James Caviezel playing the role of Christ. These examples show how subjective and changeable censorship decisions are, and how discretionary authority on what is allowed to be viewed by the general public and what is not is applied. This role played by censorship bodies across the Arab region furthermore degrades the value judgement of ordinary audiences, assuming that they cannot make their own free choices and decisions in relation to what films fit or not within their personal, societal, moral and cultural value systems.

Conclusion

Film censorship in the Arab region, initially imposed by European colonisers for political rather than moral reasons, has now become the patriarchal hand of the state that decides and guards public morals, norms and values and ensures that social critique does not defame the government, public officials or the country’s image. This trend of filtering norms and values can be said to have contributed to affect the socio-cultural context of the region in a way that pushes the public towards conservatism, rather than freedom of expression and thought. In fact, it has made the ordinary spectators dependent on the role played by state censorship, which slowly made them unwilling to accept thoughts, values or representations that lie outside the commonly held and accepted norms to which they have for so long been accustomed.

Across the region, moral codes for censorship differ not only from one country to the other, but also within the same country, based on the discretionary subjective evaluation of the censor. This dilemma has forced society to live in denial regarding the existence of societal problems and even oppose social critique or the depiction of the existing realities within society. It has, moreover, pushed for the increase of profit-oriented, commercial and escapist comedies that only aim to act as a visual anaesthetic from the harsh day-to-day life in this part of the world.

Unless film begins to reflect the Arab cultural and social context without restriction, Arab cinema will remain in complete isolation from its own people, context and reality. The question that thus remains to be answered is whether the current rise of political Islam, particularly in Egypt, will have even more restrictive consequences on freedom of expression and thought.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Lubna El-Elaimy for her much appreciated comments.

Notes

1. In his article “The Movie Business in Egypt”, Guy Brown confirms that the Egyptian film industry remains the biggest in the Arab world. In an interview with Inas Al Degheidy, a prominent Egyptian film director, she indicated that “[t]here is no comparison between Egypt and other Arab countries in terms of the volume of production … Only two or three films a year come from Tunisia, Morocco and Syria. And these films are most likely co-productions with Belgium, France or another European country. This does not really count as an industry”. Statistics from the “World Film Market Trends” of 2009 show Egypt to be producing 35 films a year. In fact, according to the same source, “Egypt, once the centre of film-making for the entire Arab world, has reduced its output from formerly 100 films to about 40 films a year but remains the most prolific African film industry in terms of this kind of production” (Kanzler 60–1).

2. Omar Kholeif has described the role of Egyptian film in relation to Arab culture in the region as acting “as a unifying device for Arab cultures” and its cinema as representing “one of the most socially and ethnically diverse cultural regions in the world, in a manner that is divergent from mainstream cinematic representation of the ‘Other’” (1).

3. An example of a film with two versions is Atef El-Tayeb’s The Innocent (Al-Baree’,1988).

4. According to Sabry, this law is either intentionally or unintentionally formulated in a way that leaves it open to interpretation and the discretion of state censorship; in fact, if it were to be strictly implemented, it would be impossible to produce anything other than family comedies.

5. According to Islamic law, Hesba cases can be filed by anyone if they believe that God or Islam has been insulted. They usually target outspoken writers, filmmakers and poets (Sandels, Manassat).

References

1. Ali, Mahmoud. Māʼat ʻām min al-riqābah ʻalá al-Sīnimā al-Misṛīyah [One Hundred Years of Censorship on Egyptian Cinema]. Cairo: Al-Magles Al-Aala Lel-Thaqafa, 2008. Print.

2. Andary, Nezar A. A Consuming Fever of History: A Study of Five Urgent Flashbacks in Arabic Film and Literature. Cambridge: ProQuest / Umi Dissertation Publishing, 2011. Print.

3. Al-Khorough [Cairo Exit]. Dir. Hessam Issawi. Film House Egypt. 2009. Film.

4. Al-Aswany, Alaa. Imaret Yacoubian: Riwāyah. Cairo: Maktabat Madbūlī, 2005. Print.

5. Aswānī, ʻAlāʼ. ʻimārat Yaʻqūbiyān : riwāyah. Cairo: Maktabat Madbūlī, 2005. Print.

6. Baheb El-Cima [I Love Cinema]. Dir. Osama & Hany Girgis Fawzy. The Arab Company for Cinematic Production and Distribution. 2004. Film.

7. Brown, Guy. “The Movie Business in Egypt”. AMEinfo.com. 8 Dec. 2002. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. <http://www.ameinfo.com/16692.html>

8. Brown, Dan. The Da Vinci Code: A Novel. New York: Doubleday, 2003. Print.

9. “Church Fights Da Vinci Novel”. news.bbc.co.uk. BBC, 15 Mar. 2006. Web. 24 Mar. 2012.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4350625.stm>10. Curry, Neil. “A New Golden Age for Egyptian Cinema”. CNN Entertainment. 2 Dec. 2012. Web. 21 Mar. 2008. <http://edition.cnn.com/2008/SHOWBIZ/Movies/03/21/egypt.cinema/index.html>

11. The Da Vinci Code. Dir. Ron Howard. Colombia Pictures. 2006. Film.

12. The Devil’s Advocate. Dir. Taylor Hackford. Warner Bros. Pictures. 1997. Film.

13. Dokan Shehata [Shehata’s Store]. Dir. Khalid Youssef. Misr Cinema Company. 2009. Film.

14. Dunia. Dir. Jocelyn Saab. Catherine Dussart Productions (CDP). 2005. Film.

15. “Egypt debates controversial film”. news.bbc.co.uk. BBC, 5 Jul. 2006. Web. 1 Apr. 2012.

<http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/5150718.stm>16. El-Rashidi, Yasmine. “Cinema case unresolved”. Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Al-Ahram. 703. 12–8 Aug. 2004. Web. 2 Apr. 2012. <http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2004/703/eg7.htm>

17. El-Sherbini, Ramadan. “Controversial Film Fails to Hit Screens”. Gulfnews.com. 2 Dec. 2006. Web. 2 Dec. 2012.

<http://gulfnews.com/news/region/egypt/controversial-film-fails-to-hit-screens-1.269313>18. Imaret Yacoubian [The Yacoubian Building]. Dir. Marwan Hamed. Good News. 2006. Film.

19. Farid, Samir. “Creative Censorship”. Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Al-Ahram. 820. 16–2 Nov. 2006. Web. 2 Apr. 2012. < http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2006/820/cu1.htm>

20. Goerg, Odile. “The Cinema, a Place of Tension in Colonial Africa: Film Censorship in French West Africa”. Afrika Zamani. 15–6. 2007–08: 27–43. Web. 24 Mar. 2012. <www.codesria.org/IMG/pdf/2-Odile_AZ_15_16_07-08.pdf>

21. Hegab, Muhammed Monir. al-Muhṭawá al-thaqāfī lil-film al-Misṛī [The Cultural Content of Egyptian Film]. Tanta, Egypt: Muʼassasat Saʻīd lil-Tịbāʻah, 1987. Print

22. Hennebelle, Guy. “Arab Cinema”. MERIP Reports, 52 (Nov., 1976): 4–12. Print.

23. Heya Fawda [Chaos, This Is]. Dir. Youssef Chahine, Khalid Youssef. 3B Productions. 2007. Film.

24. Ibrahim Al-Abyad [Ibrahim the White]. Dir. Marwan Hamed. Good News. 2009. Film.

25. Isamailia Rayeh Gayy [Ismailia Back and Forth]. Dir. Kareem Diaa El-Din. Hassan Ibrahim & Partners. 1997. Film.

26. Kanzler, Martin (ed.). “FOCUS 2009 World Film Market Trends”. Marché Du Film, Festival du Cannes. 2009. Web. 22 Oct. 2012. <http://www.obs.coe.int/online_publication/reports/focus2009.pdf>

27. Kholeif, Omar. “Screening Egypt: Reconciling Egyptian Film’s Place in ‘World Cinema’”. Scope: 19. 2011. Web. 28 Mar. 2012. <http://www.scope.nottingham.ac.uk/February%202011/Kholeif.pdf>

28. Madkour, Mervatte (Director, The Golden Tape Egypt for Production and Distribution). Phone Interview. Cairo, Egypt. 2 Dec. 2012.

29. Mumtāz, Iʻtidāl. Mudhakkirāt raqībat sīnimā: 30 ʻāman Memoires of a Film Censor: 30 years]. Cairo, Egypt: al-Hayʼah al-Miṣrīyah al-ʻĀmmah lil-Kitāb, 1985. Print.

30. Pereli, Daniele Castellani. “Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Where The Da Vinci Code Scares”. Reset 19 Sept. 2006. Web. 24 Mar. 2012. <http://www.resetdoc.org/story/00000000056>

31. Piaf, Edith. La Vie en rose. London: ASV, 1999. Sound recording.

32. Purtill, James. “Much Ado About ‘Dunia’: An Interview with filmmaker Jocelyne Saab”. Egypt Independent. 24 May 2012. Web. 3 Dec. 2012. <http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/much-ado-about-dunia>

33. Sabry, Bassem. Personal Interview. Cairo, Egypt. 2 Sept. 2012.

34. Salem, Badar I. “Arab Filmmakers say Yes we Cannes”. Variety Arabia, Cannes Special Issue. Issue 3, Apr. 2011. Web. 3 Dec. 2012. <http://varietyarabia.com/MediaFiles/PDFArchives//aa716bfb-64e1-49db-8ee5-738b9f34956a.pdf>

35. Sandels, Alexandra. “The Curse of the Hesba Lawsuits.” Manassat. 18 Aug. 2008. Web. 2 December 2012.

<http://www.menassat.com/?q=en/news-articles/4446-curse-hesba-lawsuits>36. Samak, Qussai. “The Politics of Egyptian Cinema”. MERIP Reports. 56. (Apr., 1977): 12–15. Print.

37. Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007. Print.

38. Shohat, Ella. “Egypt: Cinema and Revolution”. Critical Arts: A Journal for Media Studies, 2 (4). 1983: 22–31. Print.

39. “Taboo-smashing film breaks Egypt records”. news.bbc.co.uk. BBC, 5 Jul. 2006. Web. 1 Apr. 2006. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/5150216.stm>

40. “The Palestinian Cinema Group manifesto” in Hennebelle, Guy. “Arab Cinema”. MERIP Reports, 52 (Nov., 1976): 4–12. Print.

41. The Passion of the Christ. Dir. Mel Gibson. Icon Productions. 2004. Film.

42. The Prince of Egypt. Dir. Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner, and Simon Wells. Dreamworks SKG. 1998. Film.

Suggested Citation

Mansour, D. (2012) 'Egyptian film censorship: safeguarding society, upholding taboos', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 4, pp. 21–36. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.4.02.

Dina Mansour is a PhD Candidate in Politics, Human Rights and Sustainability at the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy. Her doctoral research is on the politics of development and socio-economic rights in Egypt between 1952 and the Arab Spring revolution. She has an interest in the film industry, especially within the Arab region in general and Egypt in particular, given her firsthand experience in a family-owned business for film production and distribution in Egypt. Among her publications are: “Review: North Country—A Scarlet Letter Society of the Twentieth Century?” in JGCinema.com (2011) and “The Aspirations of the Muslim Brotherhood” in ResetDoC.org (2011). She has presented on the Arab Spring at the 2012 “Multiculturalism, Conflict and Belonging” conference (Mansfield College, Oxford); the paper, co-authored with Sebastian Ille (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna) and Mervat Madkour (Cairo University), is entitled “Inter-Cultural Limbo: The Dilemma of Western Education in Traditional Societies: Egypt as a Case-Study” and is currently being developed into a book chapter.