Screening the Artist: Between Presence/Absence, Immediacy/Mediation

Editorial

Saige Walton and Lucio Crispino

From 14 to 31 May 2010, the Yugoslavian-born performance artist Marina Abramović mounted a large-scale retrospective of her work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Designed to “to transmit the presence of the artist and make her historical performances accessible to a larger audience”, Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present included re-enactments of several signature works performed by younger artists (chosen and coached by Abramović) (MoMA). These restagings occurred alongside the presentation of a new piece (the eponymously titled The Artist Is Present), featuring Abramović herself.

As with other works by Abramović, The Artist Is Present involved an intense, physically gruelling performance that occurred over a lengthy period of time. For up to eight hours a day, over a period of nearly three months, Abramović sat on a simple wooden chair inside the gallery’s central atrium. Visitors were invited to occupy the empty seat opposite her with the promise of an exclusive—albeit silent—audience.[1] Day after day, Abramović met the eyes of multiple strangers, casting her face down after each encounter. Time spent with the artist was of no fixed duration: its length determined by each individual sitter. When a new visitor arrived to take their seat, Abramović lifted her head again to re-establish eye contact. Through this simple gesture and its repetition, those who helped complete the work were given the impression of “unique, personal contact”, “Boom. Like a magnet” (Senior and Kelly 76).

Abramović had no shortage of takers (around 1,500 people, in fact), eager to have an audience with the high priestess of performance art. In the documentary that was released after the exhibition, Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present (Matthew Akers and Jeff Dupre, 2012), the filmed encounters make for compelling viewing. Costumed in pseudo-clerical garments, Abramović’s alternating red, white and black clothing, as well as her dark, side-swept hair, stand out against the gallery’s walls and floor. As both the documentary and surviving exhibition footage attest, The Artist Is Present triggered a range of emotional and gestural responses. Some participants stared reverently and intently at the artist, as if communing with a saint or a deity. Others seemed to experience a moment of pseudo-spiritual ecstasy or transcendence. Others tearfully put their hand to their heart or chest, a gesture that suggested a moment of genuine, emotional unburdening. Others were less enthused.

Of particular interest to us with regard to The Artist Is Present (as signalled by our choice for this editorial’s cover image) is the particular tension that all these aforementioned encounters had in common. On the one hand, The Artist Is Present was promoted, staged and received as a collaborative, affectively intense and ostensibly private moment with Abramović. According to the MoMA press release, each visitor’s sitting “completes the piece and allows them to have personal experience with the artist and the artwork” (“MoMA Presents”). And yet, each moment of unfiltered contact was, of course, profoundly mediated. All Abramović’s “communers” were embedded within larger sets of curatorial and institutional strategies. Gallery invigilators and security guards were constantly on hand to police the work and preserve its formal and thematic integrity (Abramović’s and the gallery’s ostensibly shared sense of presence and “stillness”).[2] Despite Abramović’s own minimalistic performance, the piece was pervaded by a heady theatricality: an effect enhanced by sets of bright lights, a bevy of cameras and throngs of observers.[3]

Figure 1: The immediacy/mediation of The Artist Is Present.

Dir. Matthew Akers and Jeff Dupre. Show of Force, 2012. Screenshot.

In other words, what seemed (or might have felt like) an immediate, spontaneous experience with the artist and their “presence” was only possible through careful staging and pre-planned acts of mediation.[4]

This special issue is devoted to scholars exploring the many ways in which the artist and artistic gestures are present in film and media. For the purposes of this introduction, we ask: what exactly do we mean when we say that the artist is present? How might the artist, their body and their gestures be figured in film and media? We use the term “figure” here to flag the close, intermedial relationship that exists between film and other arts (painting, drawing, sculpture, comic books, installation, poetry), relevant to many of our contributors. Following on from the French film scholar Nicole Brenez, we understand the figure (and its close associates: the figurable, the figurative) as being connected to the activity of “drawing or tracing, as in a figural or plastic art”. As articulated by philosopher Gilles Deleuze and others, the figure is a concept that also moves beyond figuration, connecting with the embodied dynamism of movement, rhythm and sensation, amongst other formal properties. In this regard, screening the artist has the potential to destabilise representation, giving rise to abstract, materialist expressions.

We suggest that all efforts to invoke the artist and their work in film and media entail two entwined logics: an aesthetic of immediacy or mediation—what the media scholars David Bolter and Richard Grusin also refer to as “hyper-mediacy” (21). According to Bolter and Grusin, these two logics appear throughout the history of all media forms, in varying combinations. Immediacy fosters a “transparent presentation of the real”—furthering belief “in a necessary contact point between the medium and what it represents” (30, 33). By contrast, mediation or hyper-mediacy embraces multiplicity, fragmentation and processes of construction. It makes visible “multiple acts of representation” (33–4). As we detail below, these logics are not mutually exclusive in screenings of the artist. As Bolter and Grusin affirm, hyper-mediacy makes us “aware of the medium or media” but it also testifies to our “desire for immediacy” (34; emphasis added).

Consider how immediacy and hyper-mediacy inform more traditional depictions of the artist on film. Artist biopics (especially those centred on the lives of famous painters) typically rely on a reworking of archival or biographical materials—oftentimes, repeating tales of artistic passion and genius, madness, heroism and suffering.[5] By including excerpts from the artist’s personal letters or diary entries, faithful replicas of their work or hints of works yet to be, the biopic fuses melodrama with hagiography and claims to historical veracity. Time and again, however, we encounter scenes and sequences that try to make “cinematic the […] act of painting” (Cheshire 63). Positioned up close to the canvas, the actor’s fluid or feverish gestures and their movements function as a physical correlate for the inner movements of their imagination.

In Lust for Life (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), to take but one example, Vincent Van Gogh’s painting is portrayed as a “performance of energy that brings colour” to the world (including the film world) (Bukatman 310). As Scott Bukatman suggests, Minnelli’s “corporealising” of Van Gogh occurs not only through the filming of frenzied, gestural movements (the activity of painting) but through expressive camerawork, the Cinemascope ratio, vibrant colours, editing, sound and so on. In the sequences set in Arles (Van Gogh’s most productive period), the film style crescendos, erupting “in a manner not unlike Dorothy’s arrival in the Technicolor Land of Oz” (305). Paradoxically, what all these mediating strategies cultivate is a sense of being-with the artist. In these terms, the biopic seeks to immerse viewers in not only the artist’s biographical details but a more “painterly” way of seeing.[6] Artistic inspiration and the labour of art making take on heightened, cinematic properties.

By contrast, documentaries about artists often embrace an aesthetic of transparency as a means of making visible the artist’s creative process. In Hans Namuth’s documentary Jackson Pollock 51 (1951), an aesthetic of transparency is made literal. Namuth opens his film with a fluid, unedited take of Pollock’s hand. Shot through a pane of glass (a technique pioneered, previously, in Paul Haesaerts’s footage of Pablo Picasso), Pollock performs his signature for the camera. In the lower edges of the frame, a paint tin glistens, moving in and out of visibility. After Pollock paints the film’s title across the glass (anticipating the film’s release date), Namuth cuts to Pollock outside of his studio in Springs, New York. This footage is followed by a close-up of Pollock’s worn, paint-spattered boots.[7] In Jackson Pollock 51, it is not the hand, the body or Pollock’s boots that denote the artist’s presence. Rather, it is Namuth’s conjunction of painting, film and glass that gives us immediate access to Pollock’s painterly gestures and materials.

As Rosalind Krauss observes, comparing Namuth’s film to his previous photographs of Pollock, “it was not enough to merely stand back from the process”, “tracking and recording the upright body of the painter” (294). Cinema afforded a means of “making the connection of the flung paint to the horizontal field […] absolutely manifest” (294). By shooting at ground level, filming upwards “onto the spectacle of Pollock’s painting” (the glass), Namuth was able to record Pollock’s painterly gestures (and their markings) at the very moment they appeared (301). He (like Haesaerts) wanted to “see the painter’s body and the result of the gesture conflated on the same visual plane” (294). Immediacy and mediation are still inseparable here, however. While purporting to give viewers “direct access to the maestro at work”, it is mediation (the glass, the positioning of the camera, the positioning of the artist) that makes Namuth’s illusion of transparency possible (301).For the remit of this issue, we asked contributors to avoid representations of the artist in the artist biopic or the documentary. If approached beyond these traditional bounds, what new critical perspectives and understandings about the artist, art making or the documenting of artistic gestures might emerge? How might an aesthetic of immediacy or mediation manifest itself?

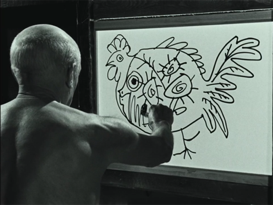

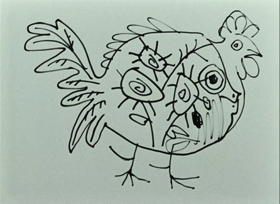

Of special inspiration to us on this front was Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Mystery of Picasso (Le Mystère Picasso, 1956) as well as André Bazin’s reflections on the film, which he once famously described as a “revolution in films about art” (qtd. in Cardullo 3). As Bazin suggests, “watching an artist at work cannot give us the key to his art” (2). Early on in Mystery of Picasso, Clouzot removes the physical presence of the artist. For the majority of the film, in fact, Picasso is either obscured by the surfaces on which he is working (canvas, paper) or edited out of sequences altogether. By obscuring the artist or by absenting him from the frame, Clouzot reinvents transparency. By means of bodily erasure, his film actually creates a greater sense of immediacy and connection between the artist’s “inner” processes and the final marks in which they result. As Brenez posits, the concept of the figure in film can evoke “an idea of the body”, though not necessarily a literal human body. Following on from Clouzot, Bazin, Brenez and other contributors, we suggest that screening the artist need not be premised on the artist’s body or a representation of that body being present in the work(s). In addition, screening the artist may not be experienced as a singular, human presence.

Figure 2: The artist is present/absent: Mystery of Picasso.

Dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, Filmsonor, 1956. Screenshots.

Figures 3–4: The artist is present/absent: Mystery of Picasso.

Dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, Filmsonor, 1956. Screenshots.

In his article “On Fire: Cézanne, Straub and Huillet”, Nikolaj Lübecker argues that Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s film A Visit to the Louvre (Une visite au Louvre, 2003) is a passionate, “non-representational portrait” of the artist Paul Cézanne. As he details, while the film contains none of Cézanne’s artworks, a female voiceover reads out Cézanne’s reflections on fifteen famous artworks in the Louvre. Drawing on thinkers such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze and Julia Kristeva, Lübecker argues that what the filmmakers share with Cézanne is a particular affinity and nonrepresentational aesthetic: a “fire-force”. For Lübecker, this “fire-force” exists beneath the level of figuration. Spanning painting and film, it is imbued with political consequences.

The blurring of the line between immediacy and mediation has particular resonance in Elena del Río’s contribution. In “Bill Viola’s Figures of Submersion as Techniques of Transindividual Affect”, del Río mobilises Gilbert Simondon’s philosophy of individuation, drawing out its resonances with the works of artist Bill Viola. Here, del Río rejects ideas of mediation altogether. For del Río, drawing on Simondon, there “is a synthesis of natural and technical elements” in Viola’s art, “without a sense of boundary or hierarchy”. Through her detailed analyses of The Reflecting Pool (1977–1979), The Passing (1991) and Self Portrait, Submerged (2013), she demonstrates how Viola’s figures of submersion across his early and his late works course with transindividual energies and affects. The artist exists as “a key transductive agent/force” in Viola’s art but, as she demonstrates, “by no means the only one”.

In assembling this issue, one of our foremost aims was to expand formal analyses and discussions of style beyond the artist’s subjectivity or matters of personal biography. Drawing on media theorist Vilém Flusser, Martine Beugnet has elsewhere written of how technically conditioned gestures shape “our handling—literal as well as affective—of […] visual content” (4–5). Similarly, Flusser’s work on gesture is a critical touchstone for many of our contributors, helping them to expand discussions of artistic gestures in film and media beyond the expression of a personal signature. In “Hands in the Machine: Maya Deren and Marie Menken’s Manual Gestures”, Saige Walton brings Flusser’s work to bear on Maya Deren and Marie Menken’s mid-1940s filmmaking. As she maintains, Menken and Deren’s experimental film aesthetic ran counter to the individualist rhetoric of postwar art and film circles (in particular, the art of abstract expressionism). Attending to Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi (1945) and Deren’s At Land (1944), she argues that both artist-filmmakers rework the gestures of the hands through the cinema’s “moving tools”. For Walton, what unites Deren and Menken’s filmmaking is not only a shared emphasis on the hands but the possibility of a de-subjectified, gestural cinema.

Using screen aesthetic components as a guide (the frame, movement, sound, duration, looping, colour, décor), we encouraged our contributors to consider how artistic gestures are also embedded in and made manifest at the level of form, historic or contemporary. Sarah Cooper takes this approach, bringing the artists Bo Wang and Pan Lu into a dialogue with the history of Chinese botanical art (in particular, the Chinese plant collection of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew). In her “Decolonial Gesture and the Screening of the Botanical Artist in Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings”, Cooper analyses how the form of Wang and Lu’s video essay/split-screen installation helps reveal “the dual sense of screening at the heart of the colonialist enterprise”. Combining Flusser’s writing on video gesture with Walter D. Mignolo’s work on decolonial gestures, she draws out the ways in which Wang and Lu’s use of Chinese botanical art undoes a Western colonial gaze. For Cooper, Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings challenges hierarchical relations between the human and the non-human, plants and people.

Finally, we asked contributors to consider how the artist’s socio-political gestures might be made manifest in film and media, through the time and labour of art making. In the issue’s opening article, Martine Beugnet and Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli weave together a film-philosophical discussion of the hands with the socio-political gestures of Jean-Luc Godard’s practice in The Image Book (Le Livre d’image, 2018). In their article “The Image Book:or Penser avec les mains”, they detail Godard’s inspiration in Denis de Rougemont’s 1936 text, arguing for Godard’s film as an exercise in “thinking with one’s hands”. For Beugnet and Ravetto-Biagioli, this exercise is implicitly connected to political and philosophical themes in Godard’s late work. Approaching the film as a multilayered assemblage of quotations and sounds, with historical, art and cinematic references (including the citation of works from the Maghreb and the Middle East), Beugnet and Ravetto-Biagioli explore the ways in which Godard questions the monolithic (Occidental) way of seeing the world, including the work of his younger self.

Acknowledgements

We would like to take this opportunity to thank all of our wonderful authors in this issue, Laura Rascaroli and the journal’s editorial board as well as our esteemed peer reviewers who all gave so generously of their time and expertise.

Notes

[1] At nearly seven hundred hours, the original performance remains one of Abramović’s longest solo pieces. A book publication also emerged from the exhibition, Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramović (Anelli et al.).

[2] “The performance is really about presence”, Abramović stated in an interview with the exhibition curator, Glenn Lowry. “You have to be in the here and now, 100 percent”. Visitors, likewise, had to be willing to participate in a certain “kind of stillness”, a stillness that emerged from “the here and now, the present moment” (Lowry).

[3] According to Amelia Jones, the work’s theatricality rendered it more of a “simulation of a relational exchange” for her, rather than an “experiential exchange with the artist” (qtd. in Senior and Kelly 77).

[4] In what may have been a first, the original MoMA exhibition catalogue included a CD featuring Abramović’s voiceover, guiding readers through the catalogue’s key pieces.

[5] Similarly, the artist’s passion for their art has been conflated with the filmmaker and/or film star’s personal passion for bringing an artist’s life to the screen, as a similar devotion to their art (Cheshire).

[6] This tradition continues in Julian Schnabel’s yellow-tinted depictions of Van Gogh and his ambient, atmospheric filming of the artist in scenes of nature in At Eternity’s Gate (2018).

[7] In Visit to Picasso (Bezoek aan Picasso, 1949), Paul Haesaerts filmed Picasso in his atelier, painting onto a vertical pane of glass.

References

1. Abramović, Marina. The Artist Is Present. 14 Mar.–31 May 2010, MoMA – Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2. Akers, Matthew, and Jeff Dupre, directors. Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present. Directed by Akers, Matthew, and Jeff Dupre Arthouse Films, DVD, 2012.

3. Anelli, Marco, Marina Abramović, Klaus Biesenbach, and Chrissie Iles. Portraits in the Presence of Marina Abramović. Damiani, 2012.

4. Beugnet, Martine. “Touch and See? Regarding Images in the Era of the Interface.” InMedia, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.2102.

5. Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press, 1999.

6. Brenez, Nicole. “Incomparable Bodies.” Screening the Past, vol. 31, 2001, www.screeningthepast.com/issue-31-classics-re-runs/incomparable-bodies. Accessed 13 May 2022.

7. Bukatman, Scott. “Brushstrokes in CinemaScope: Minnelli’s Action Painting in Lust for Life.” Vincente Minnelli: The Art of Entertainment, edited by Joe McElhaney, Wayne State UP, 2009, pp. 297–321.

8. Cardullo, Bert. “A Bergsonian Film: ‘The Picasso Mystery’ by André Bazin.” Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 35, no. 2, 2001, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333668.

9. Cheshire, Ellen. Bio-Pics: A Life in Pictures. Columbia UP, 2014.

10. Clouzot, Henri-Georges, director. The Mystery of Picasso [Le Mystère Picasso]. Filmsonor, 1956.

11. Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. Translated by Daniel W. Smith, Continuum, 2006.

12. Deren, Maya, director. At Land. 1944.

13. Flusser, Vilém. Gestures. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth, U of Minnesota P, 2014. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001.

14. Godard, Jean-Luc, director. The Image Book [Le Livre d’image]. Casa Azul Films, 2018.

15. Haesaerts, Paul, director. Visit to Picasso [Bezoek aan Picasso]. Art et Cinéma, 1949.

16. Huillet, Danièle, and Jean-Marie Straub, directors. A Visit to the Louvre [Une visit au Louvre]. Straub-Huillet Films, 2004.

17. Krauss, Rosalind E. The Optical Unconscious. MIT Press, 1996.

18. Lowry, Glenn. “Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present.” Museum of Modern Art, 2010. https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3133. Curatorial interview.

19. Menken,Marie, director. Visual Variations on Noguchi. Gryphon Productions, 1945.

20. Mignolo, Walter D. “Looking for the Meaning of Decolonial Gesture.” Hemispheric Institute, vol. 11, no. 1, 2014, edited by Jill Lane, Marcial Godoy-Anativia, and Macarena Gómez Barris, hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-11-1-decolonial-gesture/11-1-essays/looking-for-the-meaning-of-decolonial-gesture.html.

21. Minnelli, Vincente, director. Lust for Life. Metro–Goldwyn Mayer, 1956.

22. MoMA. Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present. The Museum of Modern Art, 2022 https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/964. Accessed 13 May 2022.

23. “MoMA Presents the First Large-Scale U.S. Performance Retrospective of Marina Abramović’s Work.” Department of Communication, MoMA, The Museum of Modern Art, 6 Mar. 2010, https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_387201.pdf?_ga=2.163780472.677945832.1652394926-615215040.1651977714. Press release.24. Namuth, Hans, director. Jackson Pollock 51. 1951.

25. Rougemont, Denis de. Penser avec les mains. Albin Michel, 1936.

26. Schnabel,Julian, director. At Eternity’s Gate. Rahway Road Production/Iconoclast, 2018.

27. Senior, Adele, and Simon Kelly. “On the Dialectics of Charisma in Marina Abramović’s The Artist is Present.” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, vol. 21, no. 2, 2016, pp. 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2016.1176740.

28. Simondon, Glibert. L’Individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information. 1957. Millon, 2005.

29. Viola, Bill. The Passing. 1991, videotape, black and white, mono sound, 54:22 minutes.

30. ---. The Reflecting Pool. 1977–1979, videotape, color, mono sound, 7 minutes.

31. ---. Self Portrait, Submerged. 2013, color high-definition video on flat panel display mounted vertically on wall, stereo sound, 10:18 minutes.

32.Wang, Bo, and Pan Lu, directors. Miasma, Plants, Export Paintings. Andrew Lone, 2017.

Suggested Citation

Walton, Saige, and Lucio Crispino. “Screening the Artist: Between Presence/Absence, Immediacy/Mediation.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 23, 2022, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.23.00

Saige Walton is a Senior Lecturer in Screen Studies at the University of South Australia. She is the author of Cinema’s Baroque Flesh: Film, Phenomenology and the Art of Entanglement (Amsterdam UP, 2016). Her articles on the embodiment of film and media aesthetics appear in journals such as Culture, Theory and Critique, NECSUS, Projections, Paragraph, Screening the Past, Senses of Cinema and the New Review of Film and Television Studies. Her current book deals with the embodiment and form of a contemporary cinema of poetry.

Lucio Crispino teaches in the Bachelor of Film and Television program at the University of South Australia. He is an independent scholar whose research interests include the intersection of art and film.