Memories of a Buried Past, Indications of a Disregarded Present: Interstices Between Past and Present in Henri-François Imbert’s No pasarán, album souvenir

Veronika Schweigl

Introduction: The Spanish Retirada and Imbert’s No pasarán, album souvenir (2003)

Henri-François Imbert’s essay film, No pasarán, album souvenir (2003) deals with a relatively unknown and often overlooked historical event: the Retirada. The Spanish term “Retirada” refers to the exodus of Spanish refugees that occurred as a result of the collapse of the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic and Franco’s victory in the Spanish Civil War in 1939. Between 27 January and 10 February, approximately 400,000 Spanish Republicans fled to France. At the beginning of this period, the majority of them ended up in internment camps or so-called “concentration camps” in the south of France (for example, in Gurs, Agde, Argelès, Bacarès). Later on, they were placed into camps dispersed throughout all of France. Although the first Nazi concentration camp, Dachau opened six years earlier in 1933 under the appellation “concentration camp”, the term did not have the same connotation as after the Second World War. Nevertheless, living conditions in these camps were miserable, and numerous refugees died as a result of illness and malnutrition, as well as suffering from contempt and humiliation by soldiers guarding the camps. After the German occupation of France, thousands of Spanish refugees were transferred—with the approval of the Vichy government—to the more sinister Nazi concentration camps in Germany and Austria, such as Mauthausen (Lannon 86).

These historical facts have largely been forgotten, and accounting for this period of history has arguably only begun in recent years. Further to this, a small number of films have addressed the fate of Spanish refugees in France, for example: Filip Solé’s Camp d’Argelès (2009), Jean–Jacques Mauroy’s Mots de Gurs, de la guerre d’Espagne à la Shoah (2003), Linda Ferrer-Roca’s Photographies d’un camp: le Vernet d’Ariège (1997) and Bernard Mangiante’s Les Camps du silence (1988). While most of these films remain relatively unknown, Imbert’s No pasarán, album souvenir is slowly gaining appeal beyond France. Ten years after its release, the film’s contemporary significance lies in the fact that the existence of these French concentration camps, and the internment of Spanish Republicans in them, is still a relatively underexposed piece of history. Particularly with regard to the disappearance of the original witnesses, Imbert’s film plays an important role in recalling these events. In addition, No pasarán, album souvenir is still highly topical, because in contrast to other films addressing the Retirada, it draws parallels with the contemporary situation of refugees in France. By interviewing Kurdish and Afghan refugees at the Red Cross camp in present-day Sangatte, in the North of France close to the Channel Tunnel, the film calls attention to the difficult living conditions of today’s refugees. However, it is not Imbert’s intention to equate the French concentration camps with the refugee camp in Sangatte; rather, he aims to encourage critical reflections about contemporary refugee status. In an interview with Catherine Bizern, Imbert clarifies that:

It is not about saying “Sangatte = Argelès 1939”, it is just about saying that people come to Sangatte because where they are from, there is chaos and they are fleeing because their lives are in danger, and if one does not help them, one sends them back to that danger. Whether they are Kurds who escape from Saddam or Afghans who escape from the Taliban, one sends them back to the same danger that the Spaniards faced in 1939: to the danger of death, to political oppression, to fascism. [1] (Qtd. in Bizern 8)

Even today, ten years after the release of No pasarán, album souvenir, the precarious situation of refugees has not changed, and the resonance of Imbert’s film remains just as relevant as it did in 2003.

Imbert’s strategy of linking the fate of Spanish Republican refugees to the current situation of refugees in France, along with his practice of combining documentary and archival material—such as postcards and newspaper articles—with present-day film material, photographs and interview passages, creates a multitude of interstices between past and present. The aim of this article is to take a closer look at these interstices, and to analyse how No pasarán, album souvenir oscillates between spatio-temporalities. Specifically, I will highlight how the film can be read under the rubric of past and present, and the ways in which Imbert’s technique functions as a transport mechanism through which memory resurfaces in the present, exploring the strategies that Imbert employs to reveal the “buried past” of the Retirada and to relate it to the (oftentimes, disregarded) problems of contemporary refugees.

Firstly, I will investigate Imbert’s method of filmmaking, with regard to the importance of travelling and collecting as methods of tracing the past in the present; in the context of which, and theoretically speaking, I will engage with Walter Benjamin’s figure of “the collector”. Secondly, I will interrogate the notion of the postcard as medium—with particular focus on montage and the “invisible” present between photographs—in that not only does its existence initiate Imbert’s curiosity and thus his film, but it also functions as an important symbol of the spatio-temporalities that are at play throughout Imbert’s journey. Thirdly, I will elaborate on the relation between film and spectator, wherein I will consider the postcard as medium to transfer the concealed knowledge of the past to the present spectator. [2]

Travelling and Collecting as Methods of Tracing the Past in the Present: Imbert and Benjamin

Tracing the past in the present is a common topic throughout Imbert’s oeuvre, and the motif of travelling is a central and recurring element in his films. In Sur la plage de Belfast (1996), Imbert embarks on a journey to Belfast motivated by the discovery of a two-minute-long Super8 film, found in an old camera a friend of his had bought from a junk dealer in Northern Ireland. He tracks down the family captured on that film roll in order to return the film to them, while reflecting on the conflict in past and present-day Belfast. Similarly, in Doulaye, une saison des pluies (1999), Imbert undertakes a journey to Mali, motivated by a sudden childhood memory about an African family friend, from whom he had not heard for more than twenty years. By travelling to Mali, he not only searches for the lost family friend Doulaye, but he also reflects on the relations between Europe and Africa. In No pasarán, album souvenir Imbert traces the fate of Spanish Republican refugees during the Retirada, starting from six postcards he found at his great-grandparents’ house in Le Boulou, close to the Spanish border, when he was a child. The postcards belong to the Éditions APA (André Poux, Albi) and although they are not dated, the photo motifs and the captions written in French and Spanish reveal that the pictures display scenes of the Retirada. Furthermore, the numbers on the postcards indicate that they are part of a series containing a minimum of twenty-nine postcards. While in his childhood the images remained mysterious, as an adult Imbert decides to search for the twenty-three missing postcards in order to complete the series. He travels to places where concentration camps were once located, and combines documentary material such as postcards and newspaper articles with present-day film material, photographs and interview passages with contemporary witnesses of the Retirada and with present-day refugees.

Imbert’s journey is thus initiated through private memories, and he lets coincidences guide the way. All three of the aforementioned films start from personal and haphazardly found images, either images of a forgotten home movie, suddenly erupting childhood memories, or old and mysterious postcards found as a child. In an interview with Nachiketas Wignesan and Laurent Devanne, Imbert describes his filmmaking approach and emphasises coincidence as the starting point of his work:

I choose coincidentally from the things that, at the moment they occur or a long time after they have happened, continue to have resonance. It is this resonance that can be a trail to initiate a project. [3]

Imbert describes his method of filmmaking as “an invention with his body, with his personality in time and space” (qtd. in Wignesan and Devanne). [4] In Sur la plage de Belfast and in Doulaye, une saison des pluies, Imbert buys a flight ticket to Belfast and to Mali, to see where coincidences will lead him. His films therefore evolve from a process of tracing the past in the present. By travelling to different places and countries, Imbert discovers the present as he remembers the past by means of lived experiences.

In these three films, travelling is inherently related to the act of collecting, and it is in this regard that I wish to focus in more detail on No pasarán, album souvenir and to elaborate on how Imbert’s collecting of postcards and images relates to Walter Benjamin’s figure of “the collector”. Imbert’s collection of postcards concerning the Retirada began in his childhood, where he preserved six postcards belonging to his great-grandparents, and during the course of his film, he travels to different places in France and gradually obtains almost all of the missing postcards. However, it is not the aim of the film to complete the postcard series. Rather, the film concentrates on the process of collecting and on the ensuing haphazard discoveries and encounters. Similar to Walter Benjamin’s collector, who focuses on the act of collecting rather than on the collection, Imbert describes No pasarán, album souvenir as “a story of a person searching for postcards” (qtd. in Bizern 2). [5] For Benjamin’s collector, “the smallest antique shop can be a fortress, the most remote stationery [sic] store a key position” (“Unpacking My Library” 63). By browsing through shops of junk dealers, Imbert coincidentally comes across postcards of other series depicting the Retirada, as well as postcards with photographs of the Nazi concentration camp Mauthausen, which also becomes part of his collection. During the film and indeed Imbert’s journey, he emphasises the act of collecting and reiterates the absences within the collection by using statements such as: “I had the postcards number 1, 16, 22, 23, 26, and 29”; and, “10 and 11 are missing”. [6] By enumerating the postcards in his possession, the missing postcards and the gaps in the series become apparent to the spectator. For Imbert, as well as for Benjamin, the everlasting incompleteness of the collection is the impetus that pushes the collector.

Figure 1: Spanish Republican refugees on their march to France. No pasarán, album souvenir (Henri-François Imbert, 2003). Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. Screenshot.

Searching and discovering missing postcards as well as reflecting on the already existing collection are crucial and recurring elements in No pasarán, album souvenir. For instance, Imbert remarks that the APA postcard series is arranged mainly in geographical order. He analyses this order and locates the postcards number 1 to number 7 in Perthus, and the postcards up to number 15 in Argelès. After that, the postcard series follows the trail of refugees: on the coastal road, to the border post of Cerbère, in the direction of Argelès, traversing Banyuls, Port-Vendres and Collioure. However, Imbert does not follow the APA postcards in numerical order; instead, he detaches the postcards from their original sequence, organises them in a new constellation and links them to postcards of other series, photographs and film sequences. By means of the montage Imbert creates a new arrangement of postcards and images, through which he addresses the past of the Retirada and the present-day status of refugees today. Here, this element of his method of filmmaking can also be associated with Benjamin’s collector, who detaches the object “from all its original functions” and integrates it in a new system: the collection (The Arcades Project 204–5). Benjamin’s and Imbert’s new constellations thus open up new perspectives and, in turn, reveal unknown correlations and coherences. However, for Benjamin and Imbert, each single object of their collection takes on an important role. Benjamin emphasises that “for the true collector, every single thing in this system becomes an encyclopedia of all knowledge of the epoch, the landscape, the industry, and the owner from which it comes” (The Arcades Project 205). Similarly, Imbert devotes his full attention to each postcard, because for him each provides not only information about a particular moment of the Retirada but also about the epoch when the postcards have been produced, and about the history of the people and places depicted on them. Benjamin underlines the “importance a particular collector attaches not only to his object, but to its entire past” (The Arcades Project 207), because “for the collector, the world is present, and indeed ordered, in each of his objects” (The Arcades Project 207). In this light, Imbert detects a linkage in each postcard to the fate of refugees throughout history: to the past of the Retirada and of the Nazi era as well as to the recent past of refugees in France and to their present living conditions. In No pasarán, album souvenir the postcard thus serves as a medium through which Imbert looks into the past and points to the present and the future.

Over the course of the journeys he makes, Imbert not only collects postcards, but also collects, on a more basic level amidst the very nature of recording, the images he films with his camera. In a discussion with several filmmakers of the association Arbre, Imbert states that he could never throw away a single picture of his films (Baron and Magnen). [7] Therefore, he always edits two films: the film he is making and the film in which he collects the scraps (Baron and Magnen). For him, each image is precious because it conserves memory. Thus, Imbert’s gathering of images can be seen as an act of “re-collection”. Similarly, as Benjamin comments on the “spring tide of memories which surges towards any collector as he contemplates his possessions” (“Unpacking My Library” 60), Imbert’s examination of postcards triggers memories about his own childhood and past. Yet, as Benjamin writes, the “only exact knowledge there is ... the knowledge of the date of publication and the format of books” (“Unpacking My Library” 60). Even though Imbert’s postcards provide an insight into a moment of history and into his memories, the only definite knowledge is the captions and numbers written on the postcards. Like Walter Benjamin’s collector, who is interested in the “whole background of an item”, in “[t]he period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership” (“Unpacking My Library” 60), Imbert also traces the background behind his objects of collection. He travels to the places depicted in the postcards, he tries to find their editors and their negatives, and he meticulously investigates the images and the stories behind them. Layer by layer, he reveals elements of the concealed past of the Retirada, an archaeological procedure that draws a parallel to “Excavation and Memory”, where Benjamin compares the act of recollecting to digging:

He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging. Above all, he must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter; to scatter it as one scatters earth, to turn it over as one turns over soil. For the “matter itself” is no more than the strata which yield their long-sought secrets only to the most meticulous investigation. That is to say, they yield those images that, severed from all earlier associations, reside as treasures in the sober rooms of our later insights––like torsos in a collector’s gallery. (576)

For Benjamin as well as for Imbert, recollection is related to a protracted and tedious process of digging. Imbert spent several years tracking the postcards and, thus, investigating the history of the Retirada before he started editing his film. In No pasarán, album souvenir he describes this process; therefore, he does not “make an inventory of his findings, while failing to establish the exact location of where in today’s ground the ancient treasures have been stored up”, as Benjamin warns (“Excavation and Memory” 576). Instead, Imbert documents his research of the postcards and the location of their discovery, as well as undertaking journeys to the places that are visually depicted. The importance in marking one’s findings in the present is highlighted in The Arcades Project, where Benjamin describes the method of the collector: “The true method of making things present is to represent them in our space (not to represent ourselves in their space)” (206).

Postcards as Traces for an Absent Past and as Junctures to Marginalised Issues of the Present

No pasarán, album souvenir is marked by the tracking of an absent past. With a feeling of discomfort and astonishment, Imbert realises that locations of former concentration camps often do not display any hint of their past. For instance, he strings together eight postcards from different series, taken before and after the Spanish Civil War and before and after the construction of the camps. All of them are displaying the beach in Argelès-sur-Mer in the same visual axis without showing any signs of the concentration camps. Simultaneously, through voiceover, Imbert remarks that by looking at these postcards, all that he read or heard about the camps suddenly seemed to be completely unreal. Neither is the past of the concentration camps inscribed in the later postcards, nor do postcards originating before the war indicate signs of the future events. Similarly, in another scene referring to his visit to the former concentration camp in Agde, located in the south of France, Imbert remarks: “I had a very strange feeling, like passing through a territory that did not exist anymore”. Here, he points to the discrepancy between the historical knowledge about the concentration camps and the absent traces of the past. Similarly, in another scene, Imbert underlines the vanishing signs of that past in Agde, where he identifies a monument with the following inscription as the only indication of the former concentration camp: “Here was the camp of Agde, where tens of thousands of men were accommodated on their march towards liberty”. Imbert criticises the misleading text in a sarcastic fashion, and specifies that for the majority of people who were accommodated in the camps—Spanish refugees, Jews as well as Roma and Sinti—their march towards liberty ended in the Nazi concentration camps, thus highlighting the strategies of the repression during this time-period.

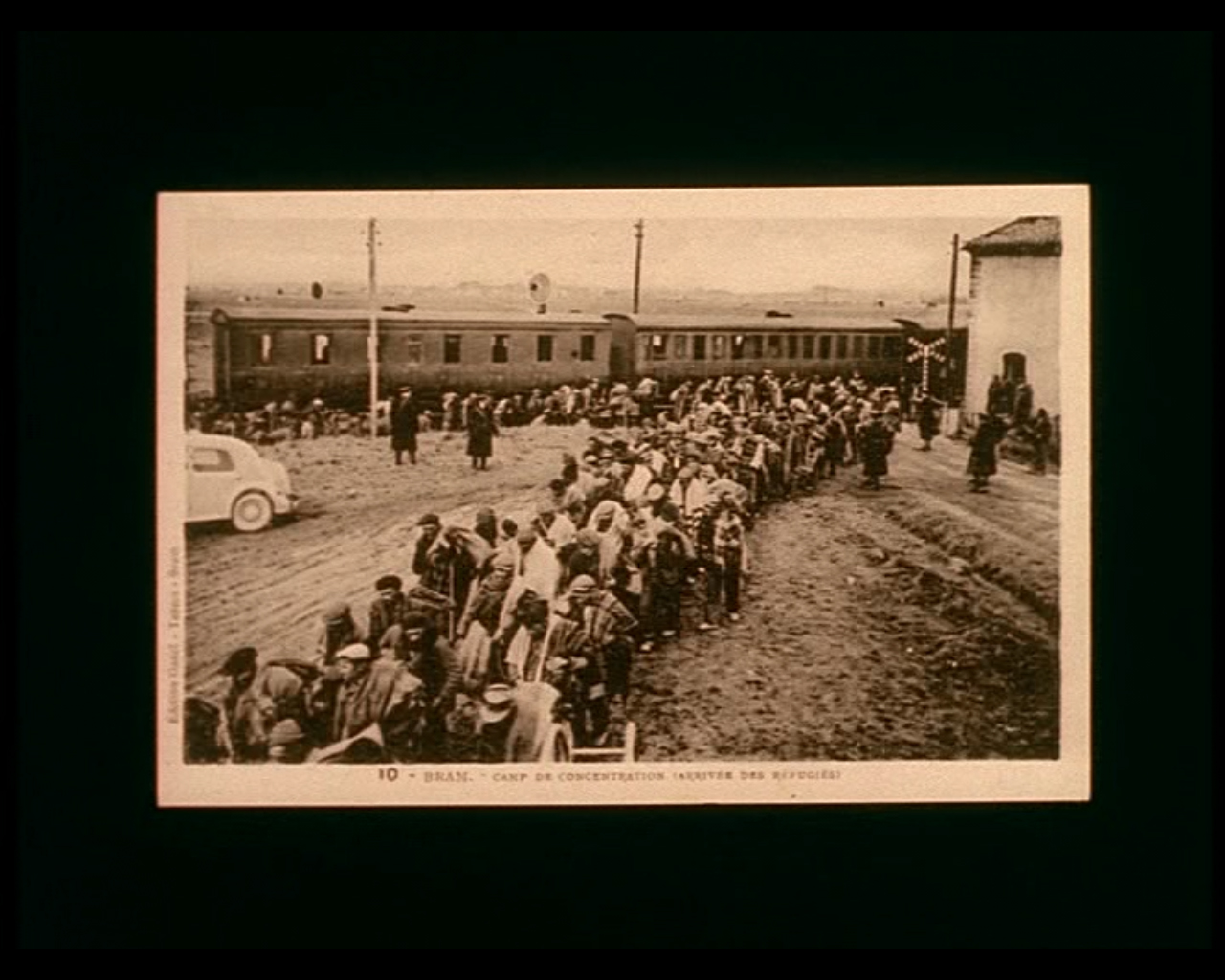

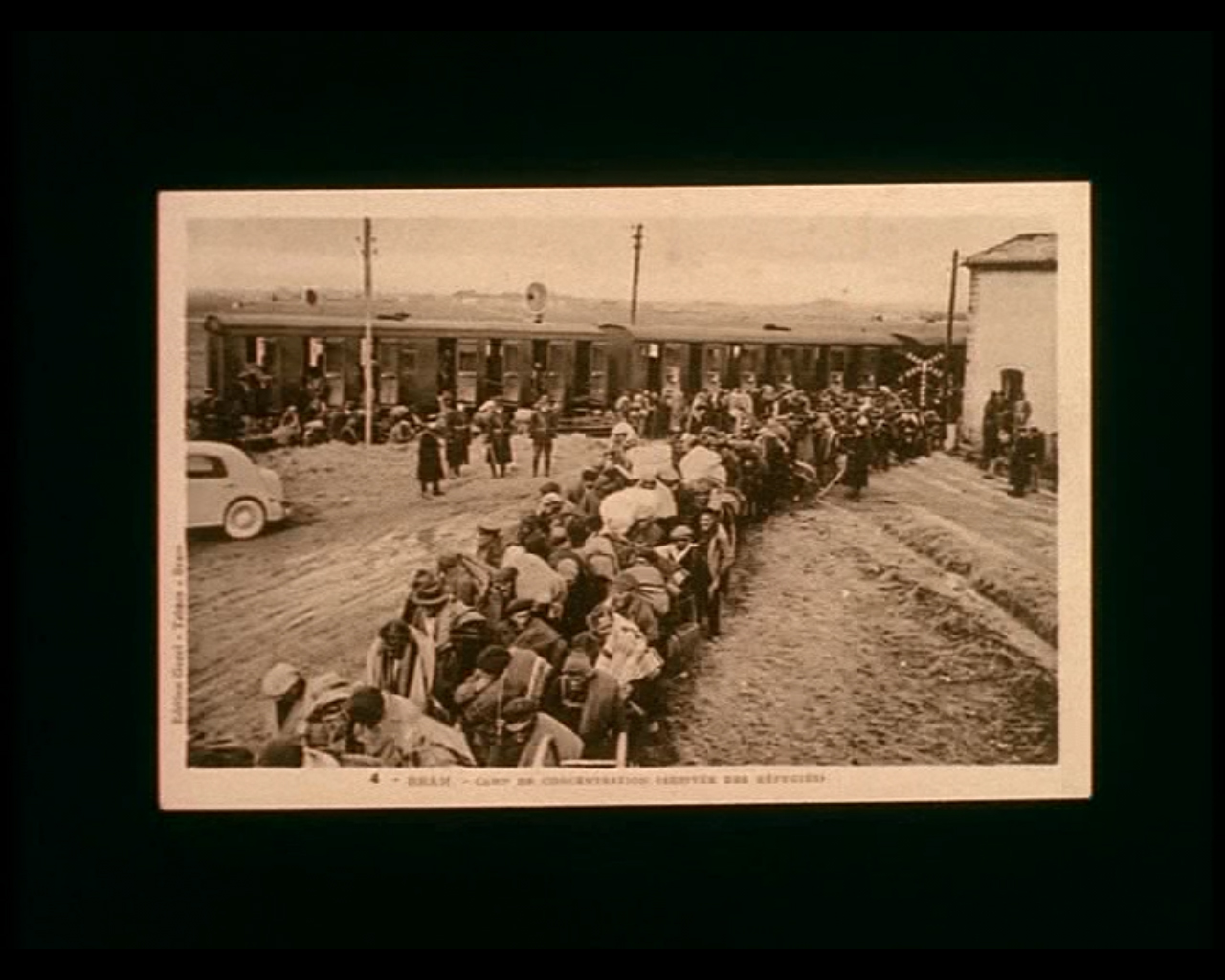

Figures 2 and 3: Postcard number 10 and postcard number 4; train arrival at the concentration camp in Bram. No pasarán, album souvenir (Henri-François Imbert, 2003). Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. Screenshot.

In terms of montage, Imbert concentrates on the interstices between the pictures and analyses what remains invisible between them. He explicitly examines the issue of the invisible between the pictures by stringing together two very similar postcards of the Retirada. The first one is labelled with the number “10” and depicts a train arrival at the concentration camp in Bram, with a long queue of refugees in the foreground. The second postcard, signed with the number “4”, displays nearly the same picture of arriving refugees: the same scene, the same frame, taken in the same angle. However, Imbert’s voiceover informs the spectator that, upon closer inspection, he realises that in the second picture the queue of arriving refugees has moved and that the expressions on their faces have changed. Between the first and second images, there is a time interval just long enough, as Imbert’s voiceover suggests, to have allowed an employee from the French railway company SNCF or a gendarme to pass by, close the doors of the train and disappear out of the frame. While his voiceover reflects upon the differences between the two postcards, the one labelled with the number “10” dissolves to postcard number 4 and then back to number 10 again. The dissolve between the images indicates an interstice between two very close moments in the past. Due to the strong resemblance of the postcards, their transition is hardly perceptible; yet while the time that passes between them is barely visible upon first glance, the film’s editing stresses the passing of time through the technique of dissolve. Imbert thus highlights the act of editing, accentuates the interstice between the pictures, and places emphasis on the “invisible” between them. His voiceover thus plays a crucial role in underlining the absent interstice. Imbert self-reflexively continues by analysing the differences between the postcards and speculating what might have happened in the time interval between them. Here, the spectator is invited to ponder, along with Imbert, on whether the fate of countless refugees might have been decided within this temporal and visual absence.

Figure 4: Refugees passing around postcards of the Retirada in the Red Cross camp in Sangatte. No pasarán, album souvenir (Henri-François Imbert, 2003). Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. Screenshot.

However, No pasarán, album souvenir does not only reflect on the past, but rather in doing so links it to the present. This is most explicit in one of the last scenes of the film, which is recorded in the Red Cross camp of Sangatte. Here, Imbert films a group of refugees while they are passing around postcards of the Retirada. In the hands of Kurdish and Afghan refugees the postcards call attention to the contemporary situation of migrants. Although the geocultural and geopolitical roots of migration differ across spatio-temporalities, there is an underlying thread in the necessity to leave their countries in order to survive, and in the prejudices and difficulties refugees have to face in their search for a new place to live. In an interview with Catherine Bizern, Imbert criticises the shutting down of Sangatte under former-President Sarkozy in 2002, and insists that we have to be critical of what our governments are doing and reflect on the status of refugees. According to him, it is not enough to simply think about what happened in the 1930s and 1940s, we also have to think about what is happening today. It is thus for this reason that he decides to conclude his film in Sangatte (Bizern 8). To this end, Maryse Bray and Agnès Calatayud emphasise in their article on the film, “Imbert’s use of his treasured postcards is not an artifice. Rather, the postcards form a constitutive part of the director’s wish to ‘delve deep between past and present, between the traces of the past and the interpretation placed on them’ …, in an attempt to not only remember but also understand the past in its relation to the present” (69).

The Postcard as Medium: Transferring the Concealed Knowledge of the Past to the Present Spectator

The spectator’s contribution to the film is crucial for Imbert. In the aforementioned interview with Catherine Bizern, Imbert explains that he tries to create a space for the spectator’s gaze, to give him or her time for his or her own reflections. Therefore, every postcard is presented for one moment in silence, so that the spectators can look at it and make their own conjectures in relation to what they have already seen in the film. Only then does Imbert’s voiceover describe the postcards, without adding further explanations to clarify the facts. Instead of moving straight on to the next postcard, Imbert dwells in silence for a further moment on the postcard. Thus, the spectator has the opportunity to doubt Imbert’s statement and to confront it with the conjectures he or she made upon the first appearance of the postcard (Bizern 3). The spectator participates actively in the construction of the film by adding his or her own thoughts and reflections. In the slow succession of postcards, the film communicates with the spectator.

Figure 5: Blank postcard—unwritten and unaddressed. No pasarán, album souvenir (Henri-François Imbert, 2003). Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. Screenshot.

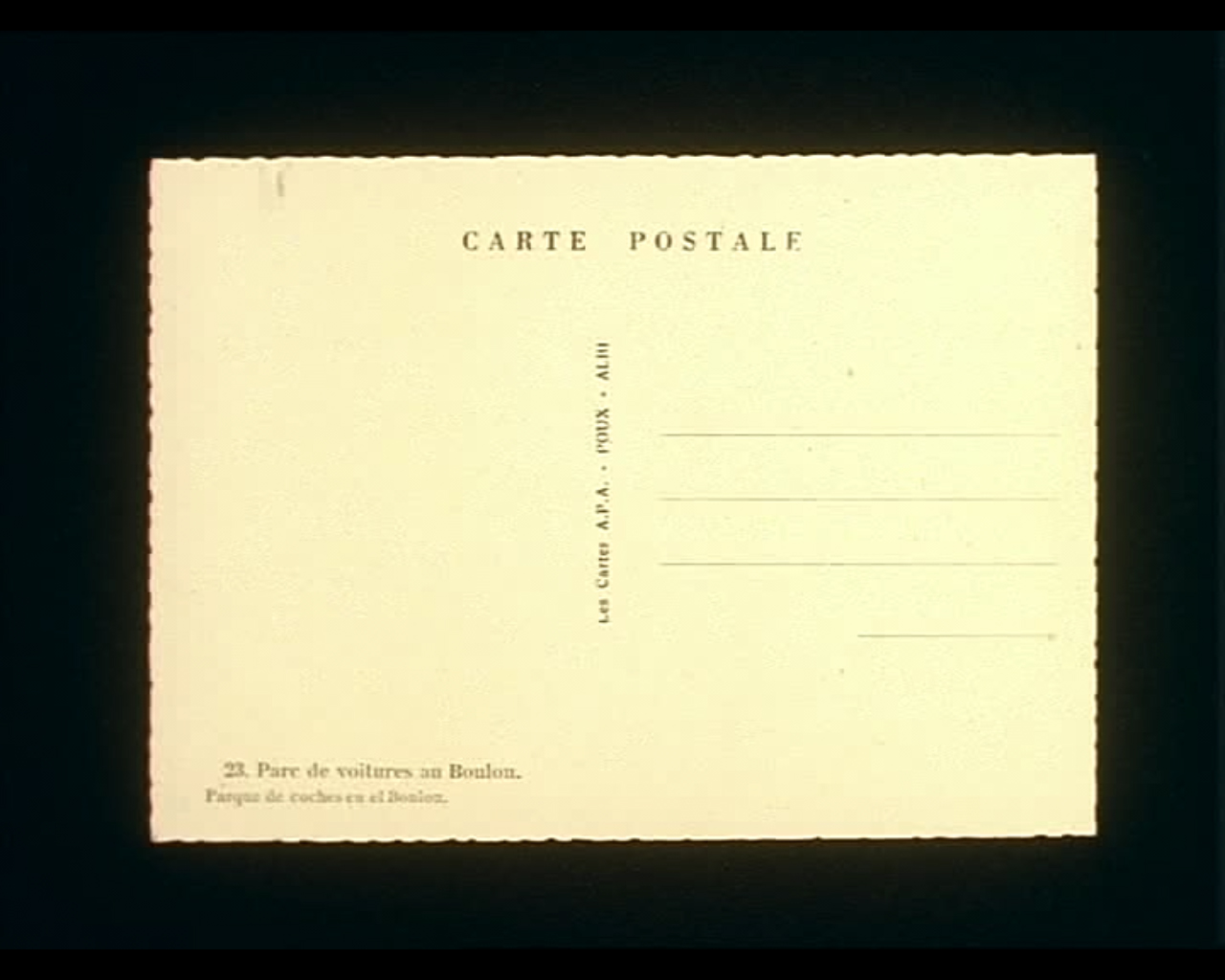

However, it is worthy to reflect upon the fact that the traditional way of communicating via postcards differs to Imbert’s utilisation of them in No pasarán, album souvenir. Whereas postcards conventionally have an established recipient and sender, who in general share a relationship with each other, in the film this is not shown to be the case. The postcards Imbert discovered are blank and have neither been addressed nor posted. [8] Furthermore, the mysterious and to some extent disturbing images on the front of the postcards are not explained in the message of the postcard, and remain open for interpretation. Since the recipient is missing too, the postcards do not give any indication of their former owners. Only the undated and short description of the context gives the spectator a hint in order to be able to locate the postcards within the historical context of the Retirada. Hence, Imbert’s postcards lack the classical characteristics of a conventional medium of communication. Instead, Imbert uses the postcards in his film to address an undefined, present or future spectator, to communicate through montage. The messages of Imbert’s postcards are open and variable because they have to be interpreted by each viewer individually in relation to the time he or she is living in.

The reason why the series of photographs of Spanish Republican refugees has been commissioned in the first place by the editors of the APA remains rather unclear. In the film, Imbert informs the spectator of his enquiry to the (then) current editor of the APA. According to him, there are no records of a postcard series of that time, but he claims that the images of this series have most likely been bought from a freelance journalist. Since the postcards of the Retirada had not been posted, it can be assumed that they had been preserved mainly as souvenirs, serving as a mnemonic device for one’s own memory. In this regard, Bray and Calatayud come to the conclusion that the postcards “had been issued to keep a record of these tragic events, as [it] was common practice in the days before the advent of MacLuhan’s global village” (65). Although the postcard is a specific medium itself that communicates between recipient and sender, in No pasarán, album souvenir it obtains the status of a document of the past or of a visual memory that communicates via film with the present spectator, rather than being concealed in Imbert’s private family album.

With this, Imbert’s approach blurs the boundary between the private and the public. On the one hand, the postcards and images described by the voiceover shed light on his personal and family background, on his childhood memories and on his experiences while tracking the missing postcards. On the other hand, they give information about historical events of the past. Already, the title of the film alludes to this linkage by combining the historical and political slogan “No pasaràn”,with the present-day view of a collection of memories, expressed through the phrase “Album souvenir”. The expression “No pasarán” is attributed to the Spanish Communist party leader Dolores Ibárruri, also known as La Pasionaria. As a supporter of the Republican troops who fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War, she ended her famous public radio speech on 18 July 1936 with the words: “Los fascistas no pasarán!”, meaning “The fascists shall not pass!” (qtd. in “Women in World History”). This battle cry, which aimed to motivate Republicans to defend the Spanish capital Madrid against the invasion of fascist forces, became the slogan for the Republican army. With “Album souvenir”, Imbert refers to a book written by Juan Carrasco, La Odisea de los republicanos españoles en Francia: Album-souvenir de l’exil républicain en France (1939-1945), which contains several reproductions of the postcard series that Imbert is collecting. In one scene of the film, Imbert’s voiceover recounts a visit that he made to Juan Carrasco’s wife, where she talked about the life of her deceased husband, who was a Spanish officer. As a consequence of his refusal to participate in the coup d'état against Franco, he had to escape to France, where he engaged in the French Résistance. At the end of the visit, Lola Carrasco offered Imbert some original postcards belonging to the series that he is collecting. Imbert accepts the postcards, feeling that for her it is a way to continue the work of her husband and to pass on the memory of the exiled Spanish Republicans in France. Similar to Juan Carrasco, who documented the past with photographs and postcards in his book, Imbert also assembles documents, postcards, photographs and film material in order to keep alive the memories of Spanish Republican refugees. Yet, within the process of his collection, Imbert raises the issue of the current living conditions of refugees in France. The film’s title, as well as Imbert’s approach—combining commentary and documentary evidence of past and present refugee status, with stories and present-day interviews—links historical and political aspects with individual and collective memory.

Concluding Comments

For Imbert, each postcard is an essential part in the large jigsaw puzzle of the history of Spanish refugees during the Retirada, which he aims to put together piece by piece. However, this puzzle will always be incomplete, because for him, as well as for Benjamin, there will always be a missing element in his collection. This is the impetus that motivates both collectors to continue searching. In No pasarán, album souvenir the driving force that pushes Imbert’s interest is the “invisible” between the pictures: the missing postcards of the APA series, the interstices between two pictures, and the always present yet “unseen” image (of the refugee of then, of now, of the future). Since Imbert’s collection is not limited to a postcard series of the Retirada, but also contains postcards of the Nazi concentration camps and images of present refugees, his collection will never be completed. The odyssey of refugees does not stop with the filmmaker’s final image of refugees in Sangatte. Day by day, new images of refugees circulate in various media and the archives continuously reveal hitherto the unseen images of former refugees. No pasarán, album souvenir is therefore but a fragment in the history of the continuum of migration. Imbert has transferred his collection of postcards and images to the present spectator whose task it is to relate it to current images and issues. Like a postcard is a means to circulate a message, his film is a medium to distribute the knowledge of the Retirada in the present. Just as the postcard is about to disappear, the figure of the collector is also vanishing. But, the collector lives on in the filmmaker and the postcard persists in the medium of film.

Notes

[1] Translated by the author.

[2] While it is beyond the scope of this article to address Imbert’s montage and engagement with the spectator from an entirely Benjaminian perspective, it is important to note Benjamin’s conception of montage as “a method of expression and address that at once interrupts a continuous flow of associations and incites the viewer to intellectual responses” (Koepnick 132); and, indeed, how his notions of disruption and “social relevance” (131) relate to Imbert’s filmic juxtaposition between past and contemporary migratory issues.

[3] Translated by the author.

[4] Translated by the author.

[5] Translated by the author.

[6] All translations into English from the film have been made by the author.

[7] Arbre is an association founded in 1998 by filmmakers (mainly documentary filmmakers) of Brittany.

[8] As Jacques Derrida has shown in The Post Card, however, nonarrival is always a possibility for what is sent; thus, even when the sender and receiver of a postcard are known to each other, the postal exchange does not guarantee the successful arrival of a message at its destination. The postcard for Derrida proves indeed the point that communication is not a closed circuit of exchange, in which the message always arrives at the appointed place. See Derrida.

References

1. Baron, Philippe, and Eric Magnen. “Henri-François Imbert: Carnets de voyage”. L’Oeil électrique. 20. Web. 7 May 2013. <http://oeil.electrique.free.fr/article.php?numero=20&articleid=350>.

2. Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Ed. Rolf Tiedemann. Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999. Print.

3. ---. “Excavation and Memory”. Selected Writings. Ed. Marcus Paul Bullock et al. Vol. 2. Part 2 (1931–1934). 1932. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2005. 576. Print.

4. ---. “Unpacking My Library: A Talk About Book Collecting”. Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1978. 59–68. Print.

5. Bray, Maryse, and Agnès Calatayud. “Images of Exile: Tracing the Past within the Present in Henri-François Imbert’s No Pasarán! album souvenir”. Studies in European Cinema 4.1 (2007): 61–72. Print.

6. Carrasco, Juan. La Odisea de los republicanos españoles en Francia: Album-souvenir de l’exil républicain en France (1939-1945). Barcelona: Nova Lletra, 1980. Print.

7. Derrida, Jacques. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Translated and with an introduction by Alan Bass. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1987. Print.

8. Ferrer-Roca, Linda, dir. Photographies d’un camp, Le Vernet d’Ariège. 1997. Les Films

d’ici, 2006. DVD.

9. Imbert, Henri-François, dir. Doulaye, une saison des pluies. 1999. Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. DVD.10. ---, dir. No pasarán, album souvenir. 2003. Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. DVD.

11. ---, dir. Sur la plage de Belfast. 1996. Éditions Montparnasse, 2006. DVD.

12. ---. “Henri-François Imbert, Cineaste”. Interview by Nachiketas Wignesan and Laurent Devanne. Kinok. Web. 23 April 2013. <http://www.arkepix.com/kinok/Henri-Francois%20IMBERT/imbert_interview.html>.

13. ---. “No pasarán, album souvenir”. Interview by Catherine Bizern. Le Cinéma de Henri François Imbert. June 2003. Web. 15 Apr. 2013. <http://www.lecinemadehenrifrancoisimbert.com/images/stories/films/nopasarandp.pdf>.

14. Koepnick, Lutz. Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Power. Nebraska: U of Nebraska P, 1999. Print.

15. Lannon, Frances. Essential Histories: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. Print.

16. Mangiante, Bernard, dir. Les Camps du Silence. 1988. La Sept/Video, 1991. Videocassette.

17. Mauroy, Jean–Jacques, dir. Mots de Gurs, de la Guerre d'Espagne à la Shoah. Cumamovi, Amicale du camp de Gurs, 2003. Videocassette.

18. Solé, Felip, dir. Camp d’Argelès. 2009. Kalimago Films, 2011. DVD.

19. “Women in World History”. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. 1996–2013. Web. 07 July 2013.

<http://chnm.gmu.edu/wwh/p/248.html>.

Suggested Citation

Schweigl, V. (2013) 'Memories of a buried past, indications of a disregarded present: interstices between past and present in Henri-François Imbert’s No pasarán, album souvenir', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 5, pp.74–86. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.5.05.

Veronika Schweigl is a PhD student in Film and Media Science at the University of Vienna, Austria, with a research focus on essay film. She recently published an article in the 57 Swiss Film Annual Book Cinema entitled Durchlässige Grenzen—Interaktionsformen zwischen Film und Zuschauer im Essayfilm (Schüren, 2012).