An Advertiser’s Dream: The Construction of the "Consumptionist" Cinematic Persona of Mercedes Gleitze

Ciara Chambers

In a plot that might have been taken from a Hollywood movie, in the mid-1920s a young British soldier serving in India writes to famous endurance swimmer Mercedes Gleitze after falling in love with her photograph. As she often replies directly to fan letters, Gleitze strikes up a correspondence with the man, William Farrance, and several months later, despite having never met him, accepts his proposal of marriage. The couple exchanges letters for nearly two years before finally meeting. Shortly afterwards, the press reports that Gleitze

has terminated her engagement because, as she says, she does not consider herself fit to be any man’s wife on account of her passionate love of the sea … “I shall never be able to settle down in a home as a wife until I have successfully swum the Irish Channel, the Wash, and the Hellespont, so what is the use of letting a man make a home for me when in my thoughts the sea spells ‘Home Sweet Home’ to me?” (“Prefers Sea to Swain” 3)

Just over a year later the British newsreels cover Gleitze’s wedding to Irish engineer Patrick Carey. The society wedding was a newsreel staple and this event provided cameramen with a chance to capture images of Gleitze, her new groom and her famous swimmer bridesmaids, the Zittenfield twins. The wedding party is depicted outside the church and crowds look on as Gleitze and Carey are interviewed. He is reticent and admits: “I think on an occasion like this I can’t say very much being so happy”. Gleitze takes over, making a polished speech that places her career firmly in the spotlight and recognises her position as a symbol of national pride: “I am very happy and I hope to make a success of married life. I am leaving today for Turkey to attempt the Hellespont and I hope to win for England this additional swimming honour”. Overhead shots depict the couple struggling through a crowd to reach their wedding car. Two policemen push back fans and wellwishers before the vehicle can move off. Gleitze seems at ease with the spotlight—even on her wedding day she is a consummate performer for her public. The newspapers reported that Gleitze was “too busy to go honeymooning” and that she had revealed that her new husband “has promised that marriage will not interfere with my swimming career” (“Miss Gleitze’s Romance” 5).

The construction of Mercedes Gleitze was characteristic of the “new woman” of the 1920s, who could put career before marriage and motherhood. Gleitze was represented in the media like a Hollywood starlet, and there was huge public interest in her swimming achievements and personal life. Strikingly photographed for press and newsreels, her image was mobilised during an age of rising consumerism to endorse a number of products. This article will explore the representation of Gleitze in the newsreels, a relatively under-researched resource, and reflect upon how this medium can open up to researchers new possibilities of “reading” the active female body. Furthermore, it will assess her representation in the press and in advertising and reveal how she harnessed her public image to fund her career. As I will examine, the representations of Gleitze, and the associated commodification of her body, served to bolster a burgeoning consumerism while, simultaneously, offering visual proof of the figure of the upwardly-mobile female that threatens to undermine (or at least challenge) the male patriarchal order.

Traditionally, research on the medium of the newsreel has been relatively sparse, mainly due to the comparative inaccessibility of the material and the sporadic nature of preservation and digitisation internationally. The British newsreels are by far the most accessible collection, through the large amount of digitised content available from various online sources (Pathé, Movietone, ITN Source) and the existence of an almost comprehensive contextual database, News on Screen, managed by the British Universities Film and Video Council. This makes the British newsreels easier to research than any of their European counterparts, and yet even the field of British newsreel research remains relatively small. [1] Despite this scant scholarly attention, the newsreels are significant documents of what audiences were told and shown about contemporary events. Often criticised for their cavalier attitude towards politics—they remained consistently upbeat and pro-establishment—nevertheless, they offer film historians a glimpse of how audiences were addressed and how the representation of certain events was inflected in order to to satisfy public taste and perpetuate particular social values. [2]

In her recent thesis on interwar American newsreels, Sara Beth Levavy refers to the newsreels as “forgotten examples of the inherent hybridity of motion pictures” (iv). They drew upon the characteristics of news reporting associated with both the press and radio, and their exhibition within a cinema programme, which was increasingly dominated by Hollywood production after the First World War, led to a tendency to include imagery associated with the glamorous and entertaining spectacle of celebrity. Whilst much consideration of the newsreels has been based around politics, propaganda and social history, this article seeks to excavate the newsreels as a source of popular culture and to explore their role in the construction of celebrity during an era of growing consumerism. It will consider how the newsreels both drew upon Hollywood cinema and differed from it, particularly in the contradictory constructions they offered of Mercedes Gleitze as a symbol of the new woman.

The Cinema Newsreel—Form and Context

The newsreel was a staple of the cinema programme from the 1910s through to the 1970s, although its popularity began to wane after the Second World War and it was replaced by more frequent television news broadcasts in the 1950s. The average newsreel lasted between five and ten minutes, was issued biweekly to match programme changes in the cinema and included four or five items covering a blend of local and international politics, sport, events and personalities. Until 1929, the newsreels were silent and intertitles described the action on screen; from the 1930s onwards they were characterised by fast-paced commentaries and upbeat music. Many of the qualities associated with the “infotainment” nature of contemporary news on a variety of platforms can be traced back to the newsreels, in particular their tendency to juxtapose the serious with the bizarre and to frequently end on lighter fare.

The release of newsreels was necessarily delayed due to the nature of the production and editing process and their distribution through a hierarchy of cinema circuits and, thus, they often covered events already known to audiences through press and radio. Consequently, audience enjoyment of the newsreels was dependent on the provision of stimulating moving images to illustrate stories and depict exotic locales and interesting personalities. In the British newsreels there was a particular focus on the Royal family and on sporting personalities; the filming of both entailed a degree of “staging”: cameramen could preplan coverage of a royal visit or sporting event. Newsreels, then, served to bolster national pride through both the evocation of the monarchy and the patriotic celebration of the achievements of individuals and, as such, seem imbued with a pro-establishment focus that may have been at odds with the political sensibilities of a range of audiences on the British distribution circuit (which included the entirety of Ireland before and after partition). In some cases, newsreel editors, aware of the impetus to placate audiences and make money, substituted stories of national interest for ones of specific local appeal. It was not unusual for a royal story to be substituted with a local sporting event for audiences in the south of Ireland, whilst audiences in the north watched the same coverage of the monarchy as those throughout the U.K. So it can be seen that, while newsreel producers usually sought to perpetuate social norms, there was certainly an awareness of the potentially sensitive nature of audience responses to certain ideological messages.

In his study of British newsreel coverage of the Spanish Civil War, Anthony Aldgate highlights issues of ideological bias in the filmic apparatus, reminding us that “with the advent of motion pictures and the cinema, it became possible seemingly to traverse time and space, and to see at first hand the events and personalities which were shaping history” (ix). Alongside this transportation for the audience, however, film was still both a corporate and technological art subject to the economic and technical conditions of its production (14). Newsreels could be easily mobilised for propaganda purposes and they were particularly potent because they were viewed in a group setting, providing an audience experience described by Richard Dyer as “vast assemblies of strangers gathered together in the dark to see flickering, rapidly changing fabulous images that they know are being seen in identical form across the world” (Dyer 8). Furthermore, given that they were shown alongside Hollywood movies, they could also be easily associated with glamour and celebrity, and this potential was not missed by newsreel editors.

Newsreels became so popular from the 1910s on that longer editions of lighter material were also produced in the form of cinemagazines. Rather than following a strict news agenda, these cinemagazines were preoccupied with entertainment, as illustrated by a statement made by the editor of Pathé Pictorial, which ran successfully from 1918 to 1969: “Our primary business is to entertain, amuse and interest our audiences” (Hammerton 171). Pathé Pictorial even had a sister cinemagazine, Eve’s Film Review, which was produced ostensibly for female audiences, but frequently pandered to a male gaze with its shots of scantily clad women appearing in a range of (supposedly innocent and unintended) provocative poses. In her book on the cinemagazine, Jenny Hammerton suggests that it sought to tap into an interest in “what was seen to be a new visibility of female sexuality” in traditionally male spheres (33). This was linked to the cultural phenomenon of the “new woman”, a term that first appeared in American periodicals in the 1890s and that was used to describe higher levels of education and independence in women who favoured pursuits that transcended the standard expectations associated with marriage and childbearing. Even if the new woman ultimately engaged in traditional relationships, she was, like Gleitze, “unruly en route to a companionate marriage” (Higashi 298). In the newsreels and cinemagazines the new woman was often used as a clotheshorse to promote the latest fashions or model the newest cosmetics, associating her with growing consumerism. As Higashi notes, in Hollywood films the new woman was depicted as “on one hand, a sexual playmate and herself a commodity, and, on the other, a sentimental heroine adhering to a Victorian legacy. Continued emphasis on self-theatricalization in both these models of womanhood served to validate consumption rather than sexual equality or freedom” (Higashi 320). A movie heroine like Gloria Swanson, then, “became an appropriate icon for an era of increased materialism”, one who herself had claimed that “working for Mr. DeMille was like playing house in the world’s most expensive department store” (Higashi 321). In this arena, the consumption of images, as well as products, could serve as a source of pleasure; this process served the function of capitalism well:

Armed with disposable income, the new woman marched in the forefront of avid consumers. Women’s access to fashion, home furnishings, and automobiles became essential now that self-making was defined in terms of personality. Display windows, including motion picture screens, thus represented the site of female desire … Perhaps this was the ultimate irony resulting from the reification of human consciousness and social relations in consumer society. Consumption reinforced the objectification of women subject to the male gaze, but the new woman was looking in narcissistic rapture at her own reflection. (Higashi 322)

The focus on the female commodity here bled into the consumer boom of the 1920s. Samuel Strauss wrote in 1924 of a new science: consumptionism, warning that “the American citizen’s first importance to his country is no longer that of citizen but that of consumer” (579). At the same time, Edward Bernays was developing his strategies of mass persuasion: his manipulation of the psychoanalytic theories of his uncle, Sigmund Freud, resulted in the establishment and growth of “public relations”, a term chosen essentially as an alternative to the pejorative connotations of propaganda. The work of Bernays became crucially important in the world of advertising and in the growth of consumerism. Bernays recognised the importance of the female market when he orchestrated several campaigns encouraging women to smoke (Tye 23–31). The female consumer was a source worth tapping and she was becoming more and more interested in growing celebrity culture.

As Higashi has demonstrated, the new woman sought images of herself in Hollywood movies, images that became inextricably linked not only with an expanding interest in celebrity, but also with burgeoning consumerism. In contrast to the movies, what the newsreels could offer were “real” images of female role models for audiences to consume, whether it be footage of the appearances of Hollywood starlets or depictions of the feats of “real life” new women like aviator Amelia Earhart. The depiction of these women, however, proved problematic for the newsreels as they struggled to achieve a balance between celebrating their achievements and reinforcing more traditional social norms. This complex balance can be seen in the newsreels’ depiction of Mercedes Gleitze where, alongside a veneration of her power as an endurance swimmer, there is an implicit and subtle neutralisation of female energy.

Mercedes Gleitze: “The Jazz Swimmer—The Mermaid that Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep”

Figure 1: Undated cartoon from Gleitze family scrapbook shared with documentary filmmaker Clare Delargy as part of her research on Spirit of a New Age (Delargy Productions, 2013).

Gleitze, famed for lengthy endurance swims in some of the world’s most dangerous waters, was depicted in a range of media in the 1920s and 1930s, but it is perhaps in the cinema newsreels that her star persona is most evident. In them, she is photogenic, highly performative and constructed in such a way as to visually emphasise her youth, beauty and femininity. She shares much with the glamorous Hollywood actors of the age and, like them, is often depicted with autograph hunters thronging round her. Her rising fame is evident in a 1928 newspaper article that describes how Gleitze required a police escort because she was “in danger of being overwhelmed” by the “clamouring crowd” (“To Swim Irish Channel” 5). Such was the public interest that the Daily Express even carried a piece on her sister’s wedding, with a photo of Gleitze as bridesmaid beside the bride and groom (“Miss Mercedes Gleitze” 4). It was this alluring star persona that made Gleitze a figure of public interest and a role model. Her reputation was further enhanced when she established a Fund for Destitute Men and Women; thereafter, her philanthropic work was also frequently discussed in the press. For example, an article titled “Famous ‘Mill Girl’” described how Gleitze undertook work in a mill for two weeks in order to better understand the challenging industrial conditions under which some of the men and women associated with her fund worked (3). She also appeared in gossip columns alongside stories about Hollywood stars like Gloria Swanson and coverage of the exploits of the Royal family. Like those movie stars, Gleitze made appearances at the cinema, notably at screenings of the film Swim Girl Swim (Clarence G. Badger, 1927) starring Bebe Daniels and featuring fellow swimmer Gertrude Erdele playing herself. It was noted that Gleitze appeared at the Plaza theatre “wearing an orange and green taffeta silk bathing costume” (“Miss Gleitze on Stage” 2). There were reports that she would feature in a similar film, although the project does not appear to have been completed (Spirit of a New Age).

Throughout the 1920s, the newsreels constructed Gleitze in heavily loaded terms. Her representation is often contradictory: whilst the newsreels celebrated her determination and afforded her role-model status, they encountered difficulties in presenting such images of an active, semi-clothed female body (she is often depicted in swimwear) and its associated connotations of upward social mobility. Perhaps in an attempt to neutralise such “threatening” images, a discourse emerged in both press and newsreels that constructed Gleitze as a nonthreatening girl: a piece in the Irish Independent proclaims: “London Girl Wins … The pluck, endurance and perseverance of a girl have realised for her the ambition of swimming the Channel” (7). Gleitze is sometimes described as a maiden, or, more exotically, a mermaid, and even “A Daughter of Neptune” in one Topical Budget newsreel (1928). Both the press and newsreels frequently comment on her youth and prettiness: the Irish Independent reports that “tastefully dressed, and wearing many trophies of her conquests, Miss Gleitze gives the impression of a refined office girl. One would scarcely detect on a first view the powerful build and latent energy that has placed her in the ranks of the world’s most notable swimmers” (“Young and Pretty” 11). Pathé’s “Channel Swim Season is with Us Again”opens with the intertitle: “Miss Gleitze—the pretty young London typist—feels certain she will do it this time”. Simmering underneath these comments is concern about the powerful energy Gleitze symbolises: so threatening is this force, it must be made youthful and girlish to neutralise its dangerous potential. In her work on representations of the body in 1920s culture, Heather Addison notes how Susan Bordo has suggested that “the female ideal of beauty becomes more slender and childlike during periods when women’s social and political power increases” (Addison 16). Clearly, with the worldwide expansion of women’s suffrage and the increased power of the female consumer, there was a heightened patriarchal tension around the burgeoning visibility of the new woman. Gleitze’s depiction in the newsreels and press as a slim, youthful mermaid neutralised her potential as an earning, independent woman whose husband not only encouraged her career, but also became her trainer. She is portrayed as young, cheerful and playful—serving to compensate for the fact that she has prioritised ambition over family life, a career over a wifely role. Interestingly, in much of the newsreel footage of her swimming, her husband is shown in a feminine, nurturing capacity: there are frequent shots of him feeding her from a boat as she swims alongside or from the edge of a swimming pool. Several shots show him positioned between Gleitze and crowds of onlookers, as he rubs protective grease on her legs and hair. While these shots present him in a nurturing role, invariably they also serve to remind the viewer that he acts as her protector; that without his full support, her endurance swims would not be possible. Most importantly, there is some sense that he “polices” his wife’s body, deciding how she will be presented and how accessible she will be to her fans.

The upbeat intertitles of newsreels also marvelled at her perseverance: “Pluck Personified” (Gaumont Graphic, 1927); “Perseverance wins. Miss Mercedes Gleitze, the plucky swimmer, who at her sixth attempt succeeded in swimming the Straits of Gibraltar” (“Miss Gleitze” Empire News, 1928). Even in failure she is congratulated for her courageous attempts: “Bravo Mercedes!”—comments a Gaumont Graphic intertitle—“Miss Gleitze starting up her plucky, but unsuccessful, swim from Donaghadee across the Irish channel” (“Bravo Mercedes!” 1928), whilst another Pathé item describes one of her channel swim attempts as “A Splendid Failure” (1927).

As well as a constant recognition of Gleitze’s determination, there is a focus on her physique and attractive appearance. Gleitze’s striking good looks made for perfect cinema, particularly in the newsreels, where, according to P.D. Hugon’s Hints to Newsfilm Cameramen: “when it comes to girls, only the most strikingly beautiful specimens should appear” (Ballantyne 40). Gleitze is repeatedly defined as the “pretty young London typist” (“Channel Swim Season is with Us Again” Pathé Gazette, 1927). Neutralisation of the potential power of the new woman occurs here in the construction of Gleitze as youthful and “pretty”, a term which has “diminutive implications; a pretty girl is one who accedes to patriarchal standards of behavior and self-presentation. Marxists think of prettiness as a quality of the commodity fetish, a central function of ideology’s ability to veil relations” (Galt 6). “The pretty” thus functions as a superficial image with power to appeal visually to an unsophisticated audience and, furthermore, to mobilise capitalist desires. In her study, Film and the Decorative Image, Rosalind Galt asserts that “beauty is a proper form of image to admire, whereas prettiness is at once a lesser, feminine form”, one that is associated in its earliest manifestations with cunning, and one that is thus “inherently deceptive” (7). Within dominant representations, then, the pretty serves a dual function as both a symbol of (superficial) charm and signifier of deceit:

Insofar as commercial cinema is constantly dismissed as too pretty—an empty spectacle, surface without depth—we might view the pretty as the aesthetic concept that best describes cinema’s articulation of visual culture and twentieth-century capitalism. (Galt 10)

Gleitze’s “prettiness” thus serves cinematic spectacle, diminishes her status as new woman and constructs her as a symbol of capitalism in a society encouraged to engage more and more with the practices of consumerism, particularly when she is used as a vehicle to sell products. Whilst the connotations alluded to by Galt of inherent deception in prettiness are absent from the newsreels, the scrutiny of Gleitze in the press certainly extended towards distrust when The Daily Mirror (her harshest critic) questioned the validity of Gleitze’s successful Channel crossing and also launched a focused investigation into her fiscal affairs, alleging misappropriation of funds and calling on Gleitze “to publish a balance-sheet to show the position of her Fund for Desititute Men and Women” (“Miss Mercedes Gleitze’s Scheme for £100,000 home” 3). Suggesting that it was “in the public interest” she do so, the Mirror continued with the story over several months and even offered to pay for an audit on Gleitze, an offer she ignored (“Stony silence of Miss Gleitze” 4). Alongside allegations of financial mismanagement were the newspapers’ attempts to blacken Gleitze’s reputation for sportsmanship: she was reported to have turned down a challenge by Lottie Schoemmell, the American swimming champion, to race across the English Channel, stating that she was interested in feats of endurance rather than speed. Stories were also carried about a feud with fellow distance swimmer Millie Hudson (“Straits Swim. Miss Gleitze Ignores Overtures from Her Rival” 7). Yet several newsreels show her and alleged rival, Hudson, swimming together (in particular attempting the Straits of Gibraltar), and the pair also appears in home movie footage, in which they are shown chatting jovially and embracing. Whilst the broadsheets largely celebrated Gleitze’s achievements, the tabloid press was increasingly hostile, often exaggerating competitive relationships or even fabricating stories to undermine more positive representations of her. Here we see the origins of what would become the tabloid approach to covering celebrity: a combination of celebration of achievement with fierce criticism and the inclusion of misleading or even completely erroneous stories. The “pretty” cinematic persona of Gleitze, which served identification desires in the audience, was placed under closer scrutiny in a press that was beginning to realise that undermining as well as celebrating the “pretty” could increase newspaper sales.

F.A. Talbot has suggested that the newsreel cameraman was more warmly received than the newspaper reporter, who “often allows his zeal and enthusiasm to overstep his discretion” (Talbot 277–86). Certainly the portrayal of Gleitze in the newsreels tends to ignore the controversies that were being explored in the press in relation to her personal life, preferring instead to focus on her exuberance and achievements. The more positive representations of her in the newsreels can perhaps be traced to the larger imperatives that drove newsreels in the era: the British newsreels in particular (outside wartime) maintained a privileged position in relation to the film censor, one that allowed them to bypass standard censorship procedures. In an effort to maintain this position (and to ensure speedy distribution), newsreels operated a form of self-censorship that sought to avoid unnecessary controversy. Furthermore, given that newsreels were screened in places of entertainment, cinema owners were keen that they would not contain material upsetting or offensive to the audience. The newsreels frequently dealt with tragic stories in an upbeat manner and always ended with lighter fare, leading the American wit Oscar Levant to suggest that the newsreels were “a series of catastrophes ended by a fashion show” (qtd. in Fielding 228). Simply put, newspapers covered the hard stories and politics; newsreels offered lighter “infotainment”.

In newsreel coverage Gleitze appears energetic, upbeat, her figure frequently on display. The depiction of her in newsreels conforms to a larger practice of representing female athletes on screen. In her study of the swimmer/film star Annette Kellerman, Jennifer Bean locates her alongside a number of other early film stars who “stood for a particular synthesis of femininity, athletic virility, and effortless mobility”: these were personalities celebrated for their “superlative physical and physical stamina” (406–7). If cinema treated audiences to credulity-stretching narratives of daring physical feats by fictional heroines (played by Annette Kellerman and Pearl White), newsreels offered the “real thing”: shots of dare-devil women like Gleitze and Amelia Earhart and stories of their achievements in the sea and in the air. As Bean suggests, the representation of these women in new visual technologies served a particularly modern function of asserting “a stance that disarms the destructive effects of technology by fully embracing its dangers” (425). Yet if Gleitze (like other action heroines, both real and fictional) was celebrated for her determination and her enthusiasm, the dangers she faced also served as the subject of many of the stories and newsreels that circulated. Just as there was much discussion around the dangers to stars on movie sets—in particular in fan magazines carrying stories of stunts that nearly went wrong—Gleitze is frequently interviewed in the press about the physical and psychological ravages of endurance swimming and the treacherous conditions associated with the open water. In an Empire News item in 1928, “Miss Gleitze Second Attempt” (sic), an intertitle reads: “Perseverance. Mercedes Gleitze makes her second attempt to swim the Straits of Gibraltar. At 2 a.m. the plucky swimmer prepares for her task—aided by a searchlight”. Gleitze is shown greasing up before entering the water in darkness, with just minor illumination from a torch. The next intertitle reads “At the break of dawn. After nearly 12 hours the swimmer’s advisers decide that further progress is impossible”. A group of men is shown conversing and, as is often the case, a determined Gleitze is depicted as wanting to continue swimming; she is dissuaded only by the physical intervention of men (who pull her from the water). The message here seems clear: Gleitze, for all her strength, still needs protection, even (and especially) from her own ambitions. To emphasise the point the next intertitle reads: “Within a mile of success Miss Gleitze is taken from the water” as the image shows her being wrapped in towels and helped into the boat by several men.

Gleitze’s advisors—always male—make a stark contrast to her portrayal on screen. Firstly, while she is shown in swimsuit, the men are fully dressed and usually in suits. The suits, with all the connotations of business attire, suggest that Gleitze is a commodity owned, or at least harnessed by businessmen. The way she is frequently surrounded by “suits” operates as a reminder that she not only mobilises consumer desires, but is also a product to be utilised by those around her: by cameramen for news stories, by advertisers to sell products and by reporters to increase newspaper circulation. In an item titled “Muscular Mercedes” (Gaumont Graphic, 1928), Gleitze is shown having her legs and neck worked on in a physiotherapy session and then exercising in her swimwear on the beach whilst the same suited physiotherapist watches. A startling juxtaposition is presented between the semiclothed, moving female body and the more static, suited, observing male.

Figure 2: “Muscular Mercedes”. Gaumont Graphic. 25 Jun. 1928. Source: jiscmediahub.ac.uk; www.itnsource.com

Figure 3: “Muscular Mercedes”. Gaumont Graphic. 25 Jun. 1928. Source: jiscmediahub.ac.uk; www.itnsource.com

The intertitle introducing the item states “If legs mean anything, Miss Gleitze, training at Blackpool, is well set for her Irish Sea swim”. Both while she is being worked on by the physiotherapist and while she exercises on the beach, Gleitze’s legs occupy the centre of the frame, and the viewers’ gaze is directed to their movement. Liz Conor explains that “the accuracy of photographic technologies opened new realms to view, including the ‘mysteries’ of the feminine body” (25). Conor cites a 1928 advertisement aimed at film exhibitors that used the new visibility of women’s legs as “an allegory of modern visual access” offering the spectator more realistic images in the cinema since the advertisement states (25), over an image of a pair of legs depicted from just above the knee, “She had a dimple on her knee ... but nobody knew it in the blind days. Today things happen in the open”. The advertisement lists a range of films concluding “that’s ‘out-in-the-open’ product gentlemen—that’s material with BOX OFFICE written large upon it” (26). This closer scrutiny of the female body offered voyeuristic pleasure but also carried connotations of the changing nature of modern femininity; it is obvious these competing contradictions struggled to coexist in a variety of cinematic representations.

Gleitze’s legs frequently feature in newsreel shots of her clad in bathing suit on the beach or emerging from the water after a swim. The movement in “Muscular Mercedes”, particularly the frenzied activity of her exercise on the beach as she performs jumping jacks and touches her toes, is especially interesting given that the newsreel may well have been screened in cinema programmes alongside “flapper” films. Here, Gleitze’s rhythmic movement has much in common with flapper dances. Lori Landay outlines a change of focus on modern bodily experiences of movement—affected by dance and exercise—that was particularly relevant in viewing experiences of the flapper film: “the new kinaesthetics created a distinctly modern experience of spectatorship” and suggests that female spectators were particularly engaged by movement on screen (234). Moving, athletic female bodies took on a kinaesthetic power that was reflective of the modern woman’s heightened social mobility. Whilst the flapper heroines occupy the spaces of narrative cinema, Gleitze is a real life version of the kinaesthetic, upwardly mobile new woman. In place of the flappers’ dance routines are Gleitze’s exercise routines and her swimming caught by the newsreels with a similarly fascinated gaze. Yet alongside these captivating images of the body in motion is footage of Gleitze in more static poses. Almost all of the newsreels juxtapose shots of her in swimwear with shots of her sporting more modest fashionable attire. When in swimsuit, she is energetic, swimming or exercising, her long voluminous hair flowing or in loose plaits. When she is clothed she is still, her hair pinned usually in two neat buns at either ear, sometimes wearing a hat and almost always surrounded by men and posing for the camera. When she swims she moves, and is an agent of action; when she is clothed she is still, aware of, and admired by, the camera and those around her. The newsreels frequently show how, as she is swimming or preparing for a swim, men around her facilitate that action by greasing her, feeding her, helping her in and out of the boat and wrapping her in towels. The frequent visual representation of Gleitze being greeted onshore by a group of well-dressed men is clearly one that resonated with the public since it is repeated in a cartoon by David Low in 1928 in the London Standard (3). It pictures Gleitze delicately emerging from the water in a black swimsuit, her trademark plaits swaying, to be met by a group of men wearing Admiral’s trimmings (bicornes and shoulder boards) over comical swimwear. Again, in this representation the contrast between masculine and feminine, nature and society, is clear. Despite their comical attire, the men dominate compositionally and Gleitze is literally sidelined, occupying the far right of the frame. The image is even divided by the outline of a rock, which splits the space into two masculine thirds occupied by men on dry land standing to attention, and a feminine third which depicts Mercedes moving carefully, her feet submerged in the water. [3] The implications here are not just of feminine otherness, but of imperial power and a tension between the colonial discourses of the past and the modern spectacle of the new woman. Such visual presentation surely tapped into then-dominant anxieties around challenges to patriarchal power structures and wider concerns about the breakup of the British Empire. The fact that the cartoon so aptly alludes to existing newsreel imagery is a reminder of the propaganda potential of the newsreel, which was so frequently mobilised to bolster colonial pride, particularly at moments when the Empire was under threat. Here the threatening figure of Gleitze, a symbol of the potentially subversive force of the new woman, is neutralised: in a presentation of her power and sporting achievement, she is surrounded by men, visually contained and linked to a patriarchal system (of the Empire). The exhilaration she clearly feels in relation to the elements is tempered by the constraints of patriarchy.

Such contrasting presentations suggest the excitement and anxiety that the body of Gleitze, the new woman, evoked and are indicative of how cultural discourse in the 1920s grappled with the shifting identity and contradictory nature of the modern woman. The newsreels continued to present Gleitze in sexualised terms, even after she became a mother. One newsreel, “Channel Swimmer Is Beaten by Weather” (British Movietone News, 1933), gives the viewers shots of Gleitze entering the water in an unusually light coloured swimsuit, in which she almost appears nude.

Figure 4: “Channel Swimmer Is Beaten by Weather”. British Movietone News. 7 Aug. 1933. Source: www.movietone.com

The camera lingers on the figure of Gleitze on the beach and then in the water, her face covered with a white cloth, as the commentary tells us she is using “her veil as a sunshield”. Coverage of Gleitze’s face directs the spectator to focus, fetishistically, on the movement of her body in the water. Yet these rather sensuous shots are juxtaposed with shots of her posing, out of the water, dressed in fashionable attire and holding her baby. Staring directly at the camera, she stands in the manicured garden in front of a terraced building, dressed fully in white, her hair styled in two neat buns. The body that has been a site of independence and power is now used to support the infant she carries. The sexualised imagery of the swimmer on the beach and in the water is tempered by the propriety of motherhood, depicted against an urban backdrop, again serving to neutralise Gleitze as a new woman.

Figure 5: “Channel Swimmer Beaten by Weather”. British Movietone News. 7 Aug. 1933. Source: www.movietone.com

The Consumpionist New Woman under Patriarchy

There are echoes in the story that formed part of Gleitze’s star persona—of the soldier who fell in love with her image—in Annette Kuhn’s statement that “to possess a woman’s sexuality is to possess the woman; to possess the image of a woman’s sexuality is, however mass-produced the image, also in some way to possess, to maintain a degree of control over, woman in general” (11). The ownership felt by William Farrance, based solely on a correspondence with her that was inspired by her photograph and cemented in a temporary engagement, is replicated in the ownership felt by the public over Gleitze’s persona and her cinematic image.

Gleitze’s persona was commodified, her image used as a platform upon which a number of products were endorsed, reminding us that “in a capitalist society representations are no more exempt than any other products from considerations of the marketplace” (5). She forms part of a broader culture in which the media was used to encourage the public to take up their roles as consumers rather than citizens. In that process, she also became a product to be consumed, like other celebrities of the screen. Liz Conor argues that the “Modern Girl was a global phenomenon before the invention of the term ‘globalization’” (2), and indeed Gleitze represents a drive towards consumerism and mass marketing that has been inextricably linked with the habits and practices of globalisation. At the same time, she realised she could harness this consumer potential to earn money to fund her swimming and philanthropic work, fulfilling her image as new woman and also using her portrayal in the media for her own ends, thus demonstrating an awareness of the power of her own representation.

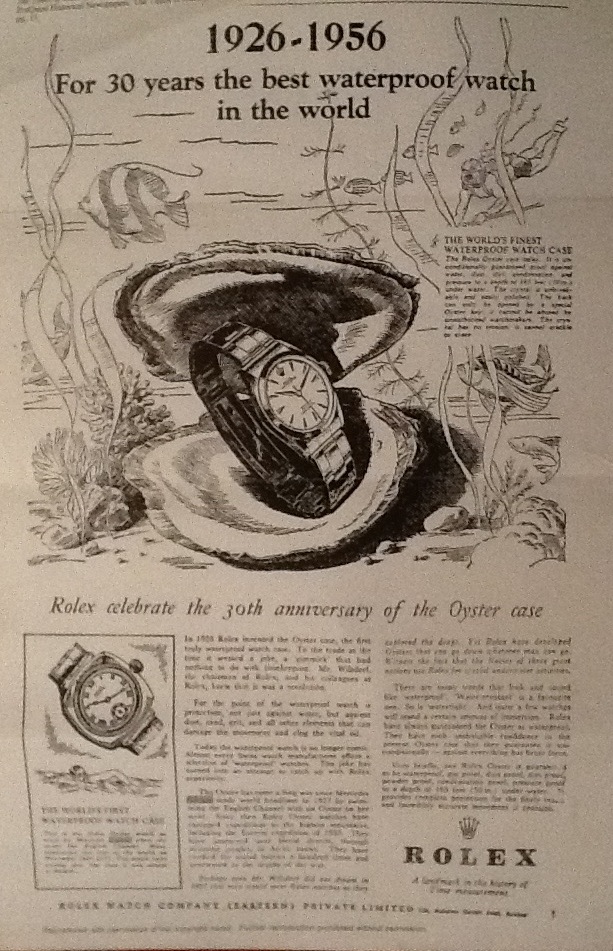

Just as the newsreels capitalised on Gleitze’s glamorous persona to provide images and stories of her feats of endurance that would appeal to audiences, advertisers used her body effectively as a site through which to sell products. Conor outlines how, in the 1920s, “for perhaps the first time in the West, modern women understood self-display to be part of the quest for mobility, self-determination, and sexual identity” (29). Gleitze’s decision to endorse a range of products thus reflects both her status as a commodified subject in a consumer society and her own appreciation of her worth and power. Interestingly, Gleitze’s first major product endorsement came after a series of news articles sought to challenge her newly won champion status: shortly after she had become the first English woman to swim the Channel (on her eight attempt) in October 1927, she was challenged by a London doctor, Dorothy Logan, who claimed that she had completed the swim in a faster time. While Logan’s claim would ultimately be revealed to have been a hoax, set up to challenge the way in which channel swim attempts were recorded, it was enough to bring Gleitze’s crossing into question and motivate her to attempt another Channel swim (“To Swim Gibraltar Straits” 5). There was much publicity in the lead-up to this swim, so much so that Rolex approached her to persuade her to wear their newly designed Oyster case watch. While the swim proved unsuccessful, the watch kept time—despite its immersion in the cold water for several hours—and Gleitze appeared on the front page of several newspapers commending its durability under intense conditions (“Rolex Introduces for the First Time the Greatest Triumph in Watch-making” 1). Rolex gave Gleitze’s arduous and challenging feats a glamorised touch, sanitising the unpleasant and uncomfortable reality of the swim whilst still focusing on the durability of the product. In subsequent years, Gleitze’s image as an endurance swimmer has been frequently reused by Rolex to emphasise its product’s durability. The company used her image in one full-page article that appeared in 1956 in The Times of India and was designed to celebrate the 30th anniversary of “the best waterproof watch in the world”.

The Oyster has come a long way since Mercedes Gleitze made world headlines in 1927 by swimming the English Channel with an Oyster on her wrist. Since then Rolex Oyster watches have equipped expeditions to the highest mountains, including the Everest expedition of 1953. They have journeyed over torrid deserts, through steaming jungles, in Arctic snows. They have crashed the sound barrier a hundred times and penetrated to the depths of the sea. (“1925–1956” 13)

Figure 6: “1926–1956”. Advertisement. The Times of India. 21 Oct. 1956: 13.

Similar Rolex ads celebrating the achievements of Gleitze appeared in the 1980s and 1990s in the New York Times and Vogue magazine. In a 2010 edition of House & Garden, a model poses as Gleitze—although she is not referred to by name—emerging from the water, wrist adorned with the trusted Rolex, an erroneous representation since Gleitze wore her Rolex around her neck during her vindication swim (Morgan). In all these images of Gleitze wearing her Rolex, the watch is presented as a product that is chosen by extraordinary individuals to accompany them on pioneering journeys; the subsequent reuse of Gleitze’s images serves to underline to potential consumers the brand’s endurance and its lineage.

Figure 7: “1927: The Swimming of the English Channel”. House & Garden (U.K.). Oct. 2010. Source: www.consumingcultures.net

While Rolex was the most significant company that Gleitze was associated with, her swimming prowess was also used to advertise mass-produced items. She appeared in ads for Reliance bathing caps (“Save Your Waves from the Waves!”), honey (“Miss Gleitze Vindicates her Honour”) and tea (“Miss Gleitze Beat the Channel on Lipton’s Tea”) in the 1920s. Such endorsements clearly established a connection between the products and her stamina and glamour. In April 1930, the front pages of both The Irish Independent and The Irish Times announced that Gleitze would appear at a “Kellett’s Corsetry Demonstration”, testifying to the wider public interest in her clothes and fashion choices. And, perhaps in an effort to appeal to male consumers, she was one of a list of swimmers that appeared in an advert for Paddy whiskey that called for a toast to those who had successfully swum the channel: “Let’s toast them in the right spirit—Pass the ‘Paddy’” (“Talks around Paddy”). As Kuhn has noted in her analysis of the identification between the spectator/consumer and the Hollywood star, the average viewer’s desire to become the star on screen is one that ultimately can only be realised through displacement “onto [a] desire for the products they advertised or connoted” (13). The average woman, then, could take inspiration to tackle her daily challenges, as Gleitze battled the elements, by drinking Lipton’s tea or eating Be-ze-be honey.

Conclusion

Gleitze’s representation in the newsreels, advertising and print press epitomises the contradictory associations connoted by the modern woman. Gleitze’s swimming feats were highly dangerous and her willingness to repeatedly enter treacherous waters was distinctly masculine in its ambition, even in a society in flux in terms of gender politics. Her enthusiasm and determination served as valuable identification traits for female spectators, but just as female ambition and representatives of the new woman were depicted—and then contained—in cinema, Gleitze was also contained within the frame by the men who surround her.

Figure 8: “Muscular Mercedes”. Gaumont Graphic. 25 Jun. 1928. Source: jiscmediahub.ac.uk; www.itnsource.com

In advertising, the figure of Gleitze is associated with athletic prowess, adventure and determination. The images of her in static poses are absent from the advertisements, which instead seek to invoke her extraordinary feats of endurance. This is particularly evident in Rolex adverts in which she appears alongside men noted for extraordinary achievements and is similarly positioned as a trailblazer, on an equal footing with figures like climber Edmund Hilary and diver Jacques Piccard (“A History of Perfomance” SM43).

A figure whose “availability” to her fans—and her consequent fame—were facilitated by mass media, she was, in turn, both empowered and neutralised by it. The constructions of Gleitze in a variety of media offer the researcher useful insights into the tensions between capitalist tendencies towards engaging the female consumer and patriarchal desires to control the potentially dangerous power of the new woman. As I have argued, Gleitze’s representation is always tempered, always ambivalent, and thus the construction of her persona is contradictory and problematic. As such, she seems representative of the paradoxical representation of a changing femininity, one which can simultaneously serve capitalist functions and disrupt a patriarchal gaze.

Notes

[1] American newsreel content is so dispersed and its digitisation so sparse that there have been only two books written on the subject,both by Raymond Fielding.

[2] An example of this was the British newsreels’ reluctance to cover the misdemeanours of the Black and Tans in Ireland in the 1920s. During the Anglo-Irish War of Independence and the subsequent Civil War, Irish audiences watched representations in the newsreels that were at odds with their daily experiences of life in Ireland, while British audiences watched a simplistic and sometimes misleading version of how events unfolded during the conflict.

[3] This cartoon can be viewed at the British Cartoon Archive’s website: http://www.cartoons.ac.uk/record/DL0073

References

1. “1926–1956”. Advertisement. The Times of India 21 Oct. 1956: 13. Print.

2. “1927: The Swimming of the English Channel”. Advertisement. House & Garden (U.K.) Oct. 2010. Print.

3. “A Daughter of Neptune”. Topical Budget. 21 May 1928. Film.

4. “A History of Performance”. Advertisement. New York Times 14 Apr. 1996: SM43. Print.

5. “A Splendid Failure”. Pathé Gazette. 24 Oct. 1927. Film.

6. Addison, Heather. “Capitalizing their Charms: Cinema Stars and Physical Culture in the 1920s”. The Velvet Light Trap 50 (Fall 2002): 15–35. Print.

7. Aldgate, Anthony. Cinema and History: British Newsreels and the Spanish Civil War. London: Scolar Press, 1979. Print.

8. Ballantyne, James. The Researcher’s Guide to British Newsreels Vol. 3. London: B.U.F.V.C., 1993. Print.

9. Bean, Jennifer M., and Diane Negra. A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema. Durham: Duke

U.P., 2002. Print.10. Bean, Jennifer M. “Technologies of Early Stardom and the Extraordinary Body”. A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema. Bean and Negra 404–43. Print.

11. “Bravo Mercedes”. Gaumont Graphic. 28 Jun. 1928. Film.

12. Callahan, Vicki, ed. Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History. Detroit: Wayne State U.P., 2010. Print.

13. “Channel Swimmer Beaten by Weather”. British Movietone News. 7 Aug. 1933. Film.

14. “Channel Swim Season is with Us Again”. Pathé Gazette. 21 Jul. 1927. Film.

15. Conor, Liz. The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s. Bloomington: Indiana U.P., 2004. Print.

16. Dyer, Richard. “Introduction to Film Studies”. Hill and Church Gibson 3–10. Print.

17. Hill John and Pamela Church Gibson. The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Oxford: Oxford U.P., 1998. Print

18. “Famous Mill Girl”. The Daily Mirror 20 Dec. 1928: 3. Print.

19. Fielding, Raymond. The American Newsreel 1911–1967. Norman, OH: U. of Oklaholma P., 1972. Print.

20. ---. The March of Time 1935–1951. New York: Oxford U.P., 1978. Print.

21. Galt, Rosalind. Pretty: Film and the Decorative Image. New York: Columbia U.P., 2011. Print.

22. Grinley, Charles. “The News-Reel”. Life and Letters Today 17.10 (1937): 122–8. Print.

23. “Happiness Machines”. Century of the Self. Dir. Adam Curtis. BBC Four. 17 March 2002. Television.

24. Hammerton, Jenny. For Ladies Only? Eve’s Film Review: Pathé Cinemagazine. Hastings: Projection Box, 2001. Print.

25. Higashi, Sumiko. “The New Woman and Consumer Culture: Cecil B. DeMille’s Sex Comedies”. Bean and Negra 298–32. Print.

26. Hugon, P.D. Hints to a Newsreel Cameraman. Jersey City, NJ: Pathé News, 1915. Print.

27. Kuhn, Annette. The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality. 1985. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

28. Landay, Lori. “The Flapper Film: Comedy, Dance and Jazz Age Kinaesthetics”. Bean and Negra 221–50. Print.

29. Levavy, Sara Beth. An Immediate Mediation: A Narrative of the Newsreel and the Film. Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 2013. Print.

30. Low, David. “The News in Pictures”. Cartoon. Evening Standard 10 Apr. 1928: 3. Print.

31. “London Girl Wins”. Irish Independent 8 Oct. 1927: 7. Print.

32. “Miss Gleitze Beat the Channel on Lipton’s Tea”. Advertisement. The Daily Express. 14 Oct. 1927: 8. Print.

33. “Miss Gleitze”. Empire News Bulletin. 12 Apr. 1928. Film.

34. “Miss Gleitze on Stage”. The Daily Mirror 25 Oct. 1927: 2. Print.

35. “Miss Gleitze Second Attempt” (sic). Empire News Bulletin. 11 Jan. 1928. Film.

36. “Miss Gleitze’s Romance”. Irish Independent 5 Aug. 1930: 4. Print.

37. “Miss Gleitze Vindicates her Honour by her Second Superb and Gallant Attempt and Pays Fitting Tribute to the Energising Properties of Be-ze-be Honey”. Advertisement. The Daily Express 24 Oct. 1927: 7. Print.

38. “Miss Mercedes Gleitze”. Advertisement. The Irish Times 5 Apr. 1930: 1. Print.

39. “Miss Mercedes Gleitze”. Daily Express 4 Nov. 1927: 1. Print.

40. “Miss Mercedes Gleitze’s Scheme for £100,000 home”. Daily Mirror 28 May 1929: 3. Print.

41. Morgan, Marilyn. Consuming Cultures: Investigating Advertising, Swimsuits, Food & Sexuality in America. Web. 9 Jul. 2013. <www.consumingcultures.net>.

42. “Muscular Mercedes”. Gaumont Graphic. 25 June. 1928. Film.

43. Pember, Doloranda. “Mercedes Gleitze (1900–1981)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford U.P. online ednJan 2011. Web 2 Dec. 2013. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/index/37/101037459/>

44. “Pluck Personified”. Gaumont Graphic. 24 Oct. 1927. Film.

45. “Prefers Sea to Swain”. Irish Independent 3 Jan. 1929: 5. Print.

46. Pronay, Nicholas. “The Newsreels: The Illusion of Actuality”. The Historian and Film. Ed. Paul Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge U.P., 1976. 95–120. Print.

47. “Rolex Introduces for the First Time the Greatest Triumph in Watchmaking”. Advertisement. The Daily Mail 24 Nov. 1927: 1. Print.

48. “Save Your Waves from the Waves”. Advertisement. Daily Mirror 27 Jul. 1928: 12. Print.

49. Spirit of a New Age. Dir. Clare Delargy. Delargy Productions, 2013. Film.

50. “Stony Silence of Miss Gleitze”. The Daily Mirror 23 July 1929: 4. Print.

51. “Straits Swim. Miss Gleitze Ignore Overtures from Her Rival.” Irish Independent 3 Dec. 1927: 7. Print.

52. Strauss, Samuel. “Things Are in the Saddle”. The Atlantic Monthly Oct.1924: 577–88. Print.

53. Talbot, Frederick A. Moving Pictures: How they are Made and Worked. London: Heinemann, 1912. Print.

54. “Talks around Paddy”. Advertisement. The Irish Times 5 Sep. 1931: 13. Print.

55. “The Test of Time”. Advertisment. New York Times 7 Dec. 1986: LI9. Print.

56. “The Test of Time”. Advertisement. Vogue 180.12 (1990): C2. Print.

57. “To Swim Gibraltar Straits”. Irish Independent 2 Nov. 1927: 5. Print.

58. “To Swim Irish Channel”. Irish Independent 10 Apr. 1928: 5. Print.

59. Tye, Larry. The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Public Relations. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2002. Print.

60. “Young and Pretty”. Irish Independent 15 Jan. 1930: 11. Print.

Suggested Citation

Chambers, C. (2013) 'An advertiser's dream: the construction of the "consumptionist" cinematic persona of Mercedes Gleitze', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 6, pp.69–88. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.6.05.

Ciara Chambers is a lecturer in Film Studies in the school of Media Film & Journalism at the University of Ulster. Author of Ireland in the Newsreels (Irish Academic Press, 2012), she has also published articles in the Journal of Film Preservation, the Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television and has contributed chapters on newsreels and amateur film to various edited collections. She has worked on archival digitisation projects with Northern Ireland Screen, Belfast Exposed Photography, the British Universities’ Film and Video Council, the IFI Irish Film Archive and University College Cork. She was part of the academic steering group for BBC’s Chronicle project, is currently a steering group member for Northern Ireland Screen’s Digital Film Archive and also sits on the advisory panel for Royal Holloway’s AHRC-funded research project The History of Forgotten TV Drama.